Impact of skeletal-related events on survival in patients with metastatic prostate cancer prescribed androgen deprivation therapy

Hong Kong Med J 2016 Apr;22(2):106–15 | Epub 4 Dec 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144449

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

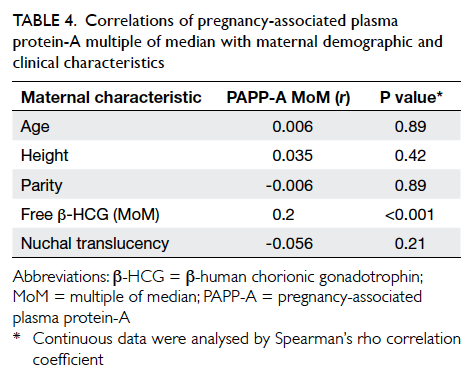

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

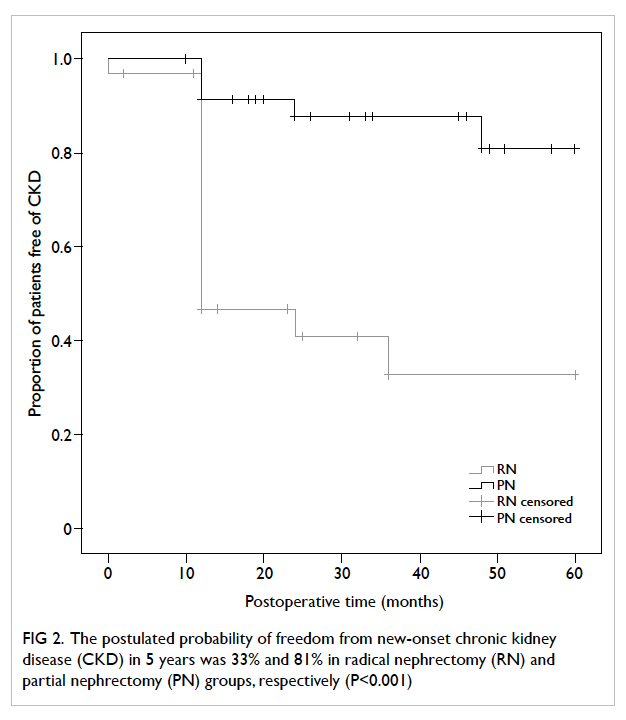

Impact of skeletal-related events on survival in patients with metastatic prostate cancer prescribed androgen deprivation therapy

KW Wong, MB, ChB1;

WK Ma, FHKAM (Surgery)1;

CW Wong, FHKAM (Surgery)2;

MH Wong, FHKAM (Surgery)3;

CF Tsang, MB, BS1;

HL Tsu, FHKAM (Surgery)1;

KL Ho, FHKAM (Surgery)4;

MK Yiu, FHKAM (Surgery)1

1 Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

2 Baptist Hospital, Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong

3 Department of Surgery, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong

4 Private practice, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr MK Yiu (yiumk2@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Objective: To investigate the impact of skeletal-related

events on survival in patients with metastatic

prostate cancer prescribed long-term androgen

deprivation therapy.

Methods: This historical cohort study was conducted in two hospitals in Hong Kong. Patients who were diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer and prescribed androgen deprivation therapy between January 2006 and

December 2011 were included. Details of skeletal-related events and mortality were examined.

Results: The median follow-up was 28 (range, 1-97)

months. Of 119 patients, 52 (43.7%) developed

skeletal-related events throughout the study, and

the majority received bone irradiation for pain

control. The median actuarial overall survival and

cancer-specific survival for patients with skeletal-related

events were significantly shorter than those

without skeletal-related events (23 vs 48 months,

P=0.003 and 26 vs 97 months, P<0.001, respectively).

Multivariate analysis revealed that the adjusted

hazard ratio of presence of skeletal-related events

on overall and cancer-specific survival was 2.73

(95% confidence interval, 1.46-5.10; P=0.002) and

3.92 (95% confidence interval, 1.87-8.23; P<0.001),

respectively. A prostate-specific antigen nadir of

>4 ng/mL was an independent poor prognostic

factor for overall and cancer-specific survival after

development of skeletal-related events (hazard

ratio=10.42; 95% confidence interval, 2.10-51.66 and

hazard ratio=10.54; 95% confidence interval, 1.94-57.28, respectively).

Conclusions: Skeletal-related events were common

in men with metastatic prostate cancer. This is the first

reported study to show that a skeletal-related event

is an independent prognostic factor in overall and

cancer-specific survival in patients with metastatic

prostate cancer prescribed androgen deprivation

therapy. A prostate-specific antigen nadir of >4

ng/mL is an independent poor prognostic factor

for overall and cancer-specific survival following

development of skeletal-related events.

New knowledge added by this study

- Skeletal-related events (SREs) in patients with metastatic prostate cancer significantly worsen their prognosis.

- The prevalence of SREs in patients with metastatic prostate cancer is high.

- Medications such as bisphosphonate therapy and receptor activator for nuclear factor κB ligand inhibitor should be considered to prevent SREs in patients with metastatic prostate cancer.

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer

diagnosed in men in developed countries. In the

United States, there were 240 890 estimated new

cases in 2011, accounting for 29% of all new cancers

in men and over 33 000 deaths.1 According to the

Hong Kong Cancer Registry in 2012, prostate cancer

was the third most common cancer in men.2

The overall incidence of advanced-stage

prostate cancer has declined in recent years, probably

due to early detection and treatment following

application of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) for

prostate cancer screening.3 Nonetheless it has been

shown that approximately 4% of patients present

with metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis1 and

5% present with localised or regional disease that

eventually metastasises.4

Bone is the major metastatic site of prostate

cancer, and has been observed in 90% of patients

during autopsy.4 Common sites of metastases include

the vertebrae, pelvis, long bones, ribs, and skull.

Bone metastases cause major morbidity in patients

with prostate cancer. They weaken the structural

integrity of bone, leading to an increased risk for

skeletal-related events (SREs) such as pathological

fracture, spinal cord compression, and severe bone

pain requiring palliative radiotherapy or surgery to

bone.5 6

The prognosis of localised and regional

prostate cancer is excellent while that of metastatic

prostate cancer is poor. The 5-year survival rate in

patients with metastatic disease has been reported

to be as low as 30%1 with a mean survival of 24 to 48

months.7 8

Evidence of the importance of SREs for

survival in metastatic prostate cancer is limited.

Oefelein et al9 evaluated men with prostate cancer

who were prescribed androgen deprivation therapy

(ADT) regardless of staging. The relative risk of

skeletal fracture for mortality was 7.4. In another

retrospective study, patients with bone metastasis

from different primary tumours were analysed.10

In the subgroup analysis, pathological fracture

increased risk of death by 20% in patients with

prostate cancer although the authors failed to

demonstrate statistical significance.10 A population-based

cohort study demonstrated that mortality in

men with metastatic prostate cancer and SREs were

approximately twice that of patients with no SREs.11

Treatments for prostate cancer were, however, not

recorded or analysed in the study.11

The aim of this study was to investigate the

impact of SREs on survival, specifically in patients

with carcinoma of the prostate with bone metastasis

prescribed long-term ADT. Prognostic factors of

survival in patients with SREs were also investigated.

Methods

The study period was between 1 January 2006 and

31 December 2011. Patients who were diagnosed

with prostate cancer and bone metastasis and who

underwent either bilateral orchiectomy or were

prescribed a first dose of luteinising hormone

releasing hormone analogue (LHRHa) injection

during the study period at either Queen Mary

Hospital or Tung Wah Hospital in Hong Kong were included.

Patients were followed up until death or the last

follow-up taken on 31 March 2014.

Diagnosis of carcinoma of the prostate was

made following transrectal ultrasound-guided

prostate biopsy, incidental histological findings

of transurethral resection of a prostate specimen,

biochemical diagnosis of PSA of >100 ng/mL, or

other histological evidence such as bone biopsy in

patients who presented with pathological fracture.

Presence of bone metastasis was confirmed either

by bone scan or by cross-sectional imaging such as

computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI). Patients who had evidence of bone

metastases at four or more sites or visceral metastasis

were regarded as having high-volume disease.

Patients with medical castration were prescribed

regular LHRHa injection every 3 months. Patients

with underlying metabolic bone disease were

excluded from study. In this study, SRE was defined

in patients who developed pathological fractures,

cord compression related to bone metastasis, and/or those who received irradiation or prophylactic

surgery to bone metastasis.6 7 Castration-resistant

prostate cancer (CRPC) was diagnosed when there

were at least two consecutive rises in PSA, at least 1

week apart, with PSA of >2 ng/mL.

Data were collected from the electronic clinical

management system database in the government

health care system. Patients who underwent bilateral

orchiectomy or received the first dose of LHRHa

within the study period were shortlisted, reviewed,

and then recruited as eligible patients according to

the inclusion criteria. Data were collected from in-patient

and out-patient records and included age

at diagnosis; performance status; any bone pain at

diagnosis; imaging such as bone scan, CT, and MRI;

volume of metastasis; details of ADT and SREs;

history of metabolic bone disease; CRPC status;

treatment received for prostate cancer; and date and

causes of death. Two authors (KW Wong and CF

Tsang) abstracted the data and were not blinded to

the outcomes.

Data were analysed using the Statistical Package

for the Social Sciences (Windows version 21.0; SPSS

Inc, Chicago [IL], US). The primary outcome was

survival time, calculated from the date of start of

ADT until death or the last follow-up. Survival was

described with Kaplan-Meier curves. Univariate and

multivariate analyses were performed with Cox

regression model to predict prognostic factors for

survival. The dependent variables were time to death

(overall and cancer-specific), defined as the time

from the start of ADT to death. Prognostic variables

significant in the univariate analyses were entered

into the multivariate Cox regression models.

Results

A total of 119 eligible patients were identified within

the study period. The mean age at prostate cancer

diagnosis was 75 (range, 49-94) years. Initial ADT

was by bilateral orchiectomy or LHRHa injection in

58 and 61 patients, respectively, with seven patients

subsequently switched from injection to bilateral

orchiectomy. The median time of follow-up was 28

(range, 1-97) months. No patient was lost to follow-up

during the study.

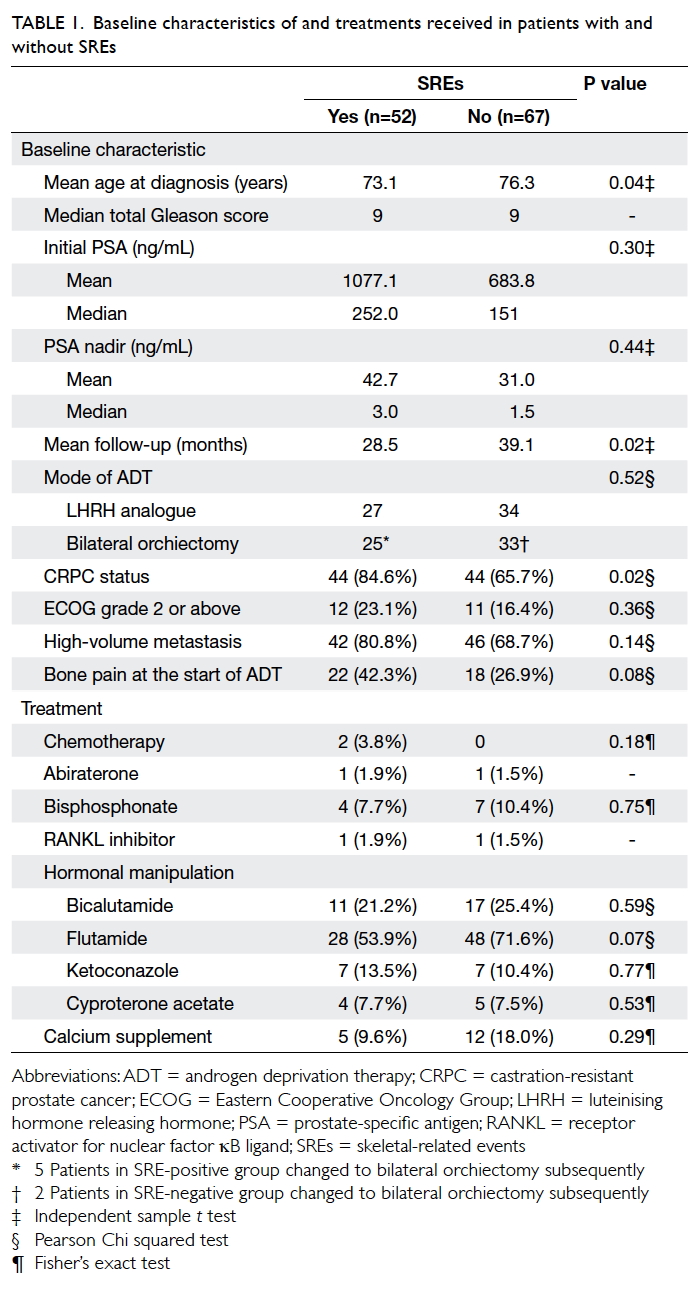

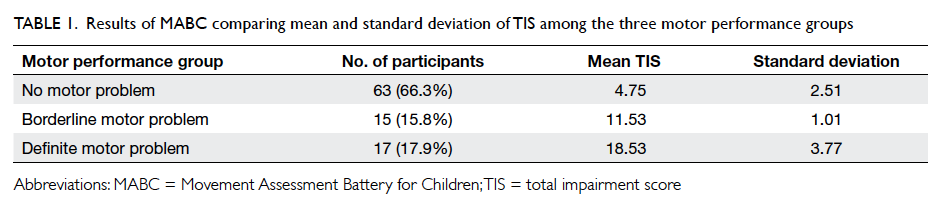

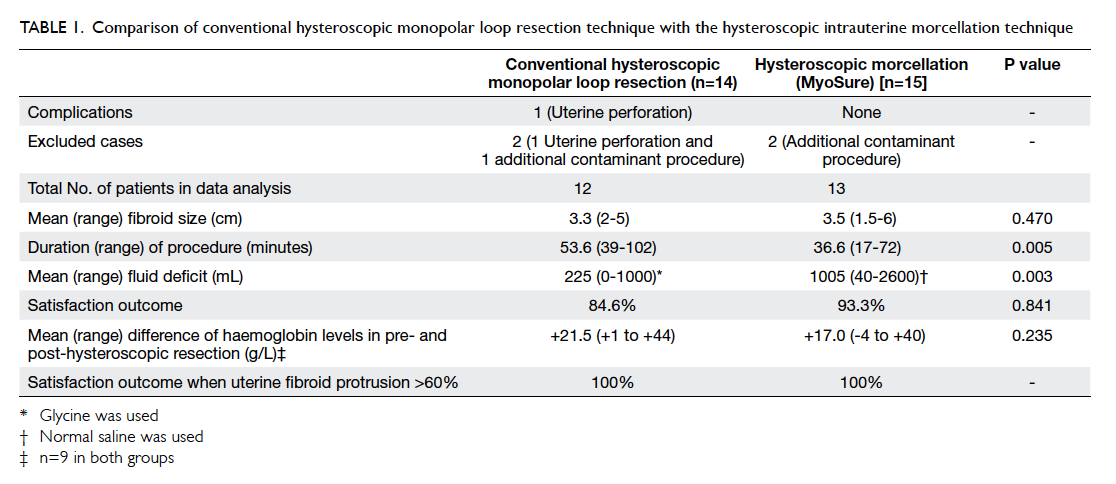

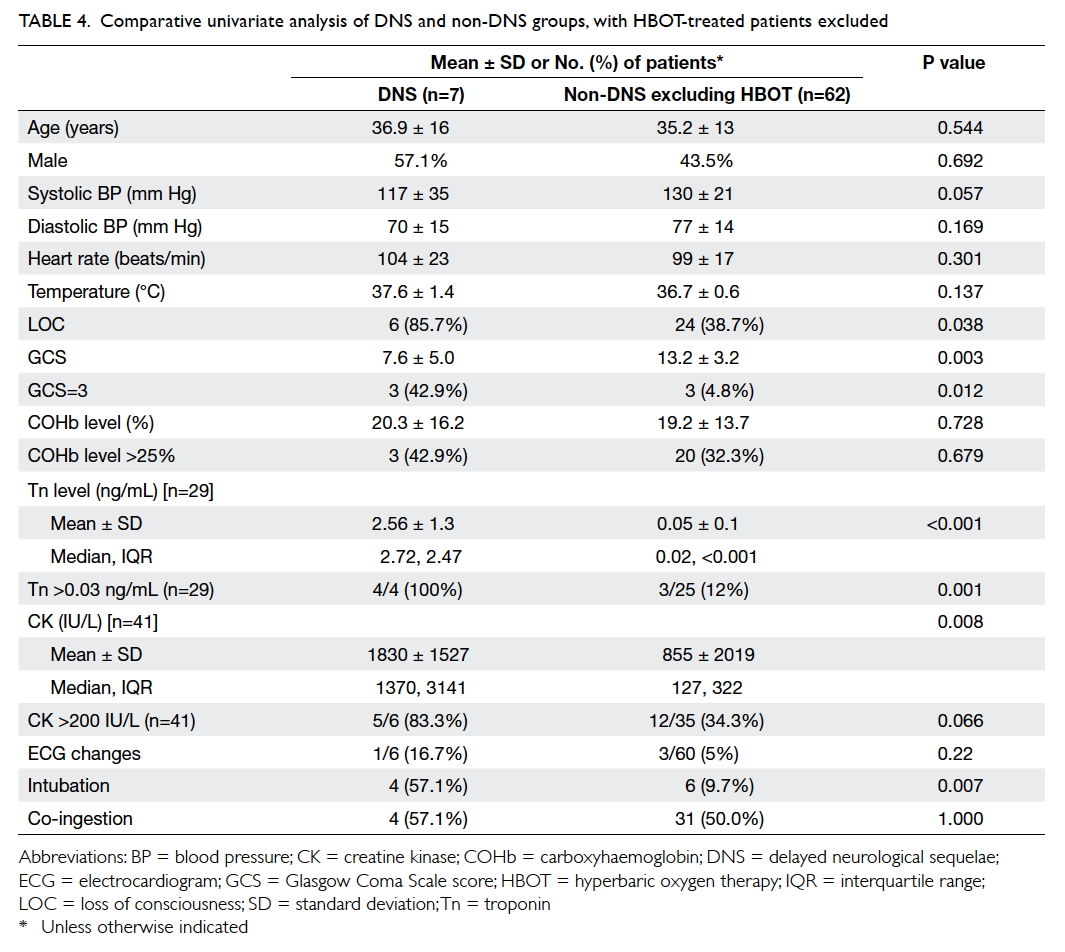

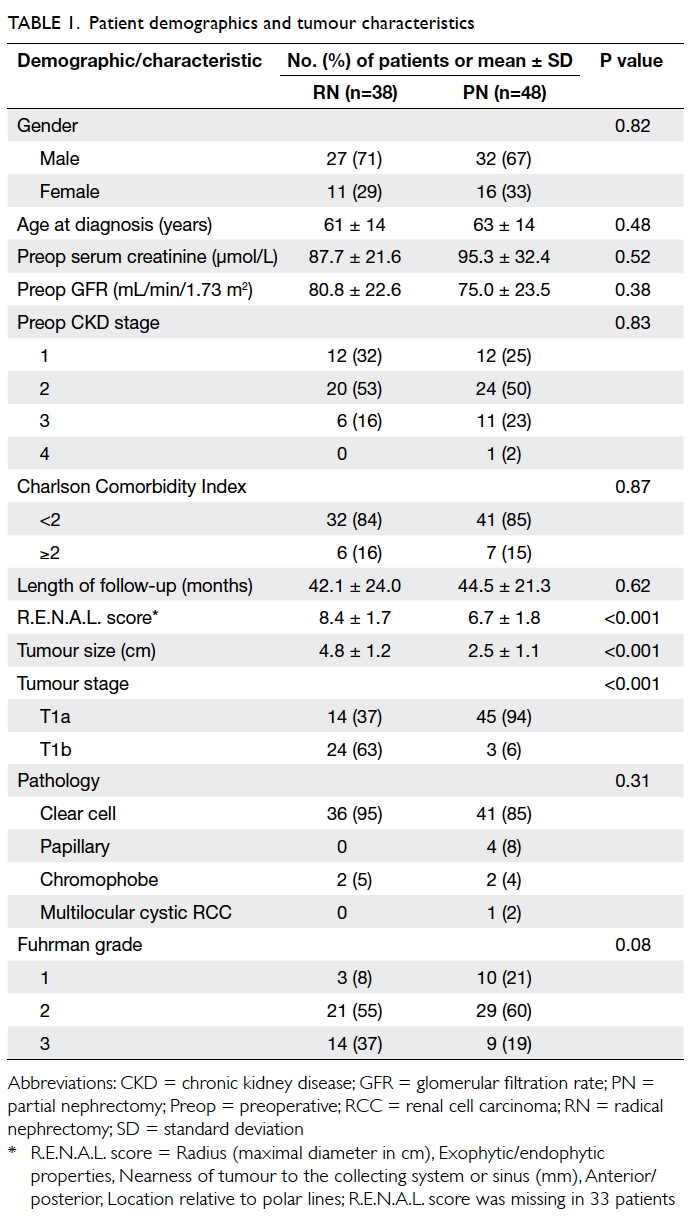

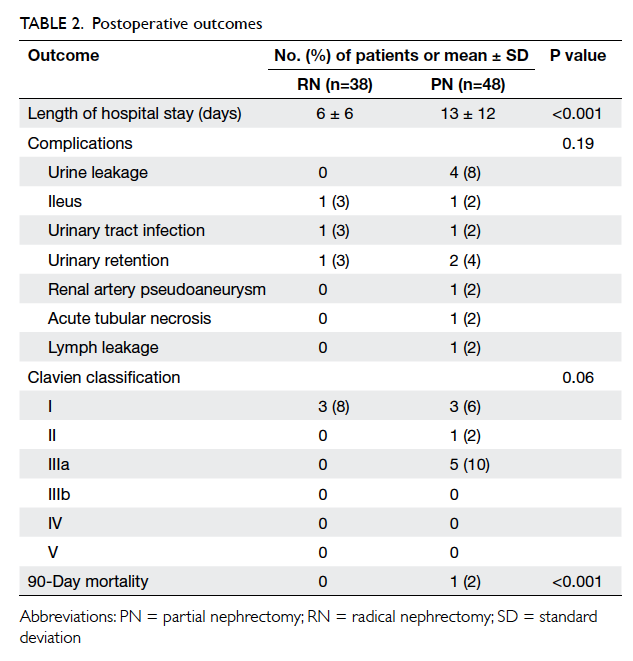

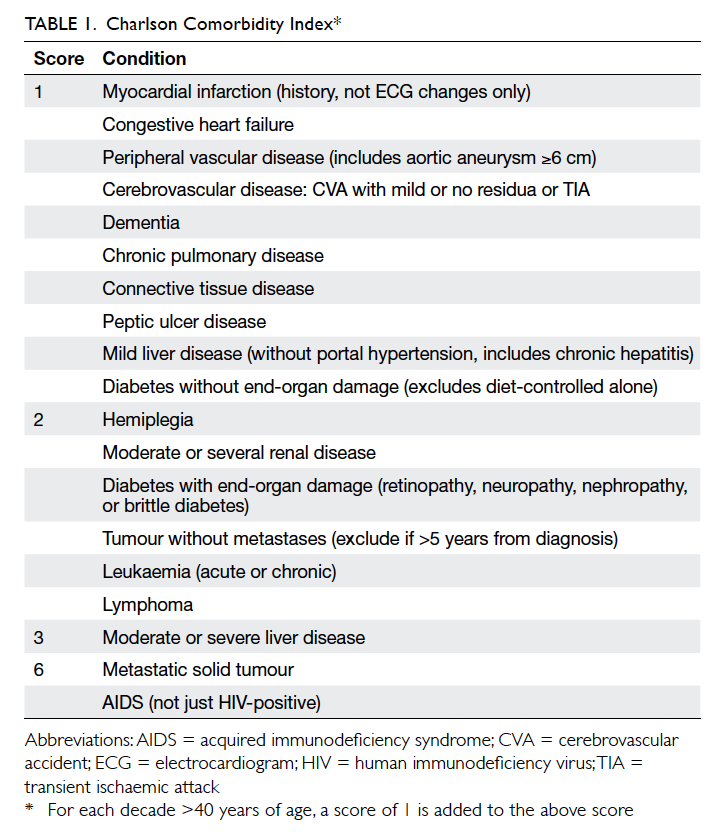

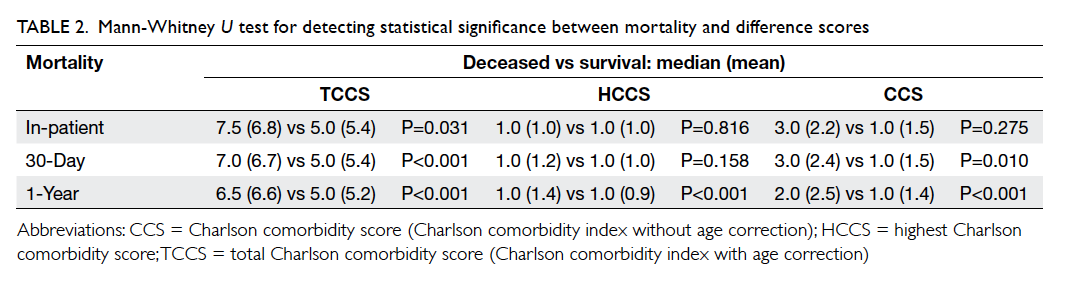

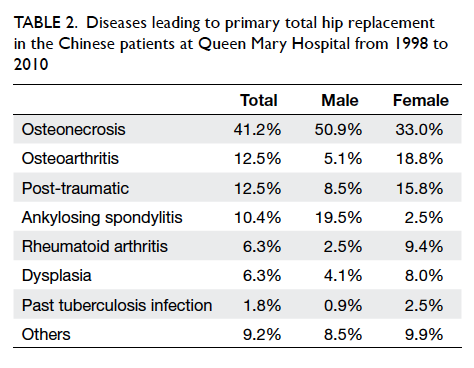

The baseline characteristics of patients are

summarised in Table 1. When stratified according to the presence of SREs, the two groups did not differ significantly in total Gleason score of prostate

cancer, PSA level at the time of diagnosis, PSA nadir,

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG)

performance status, volume of metastasis, presence

of bone pain at the start of ADT, or mode of ADT.

Patients with SREs were slightly younger at the time

of diagnosis (73.1 vs 76.3 years; P=0.04) and had a

shorter mean follow-up time (28.5 vs 39.1 months;

P=0.02). More patients with SREs developed CRPC

when compared with those who did not have SREs

(84.6% vs 65.7%; P=0.02).

The treatment received by patients with

and without SREs were compared (Table 1). Only treatments received prior to development

of SREs were included in Table 1 to analyse whether the baseline characteristics of treatment

differed before the development of SREs. The proportion of patients

prescribed chemotherapy, bicalutamide, flutamide,

ketoconazole, cyproterone acetate, and calcium

supplement was statistically similar for the two

groups. Only two patients in each group received

abiraterone and denosumab therapy. No patient

received sipuleucel-T, cabazitaxel, enzalutamide,

radium-223, or other novel treatment for prostate

cancer throughout the study period.

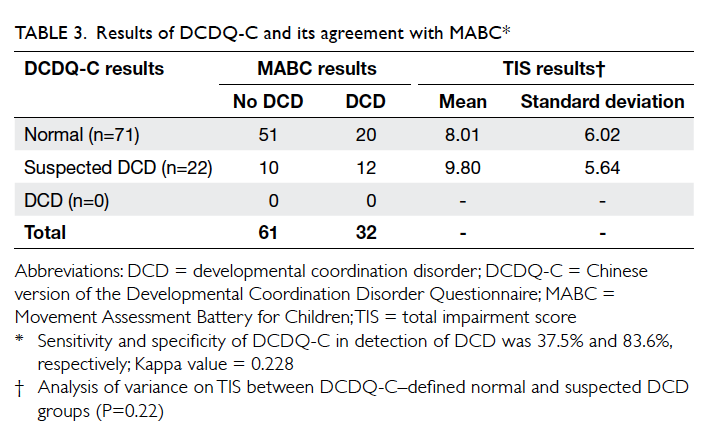

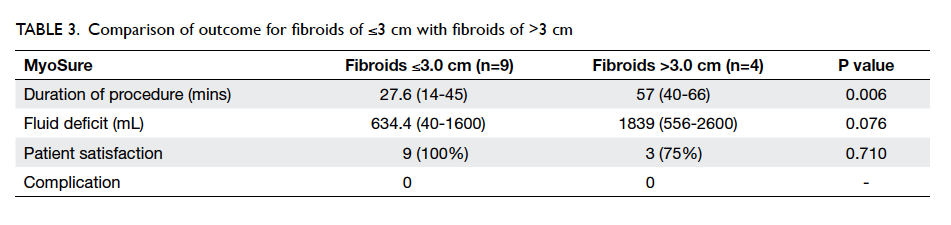

Incidence of skeletal-related events

Of 119 patients, 52 (43.7%) developed SREs. A total

of 69 SREs were recorded—36 (69.2%) patients had

one SRE, 15 (28.8%) patients had two SREs, and one

patient had three SREs. Irradiation to bone for pain

control accounted for 47 (68.1%) events; 14 (20.3%)

events were cord compression and there were eight

(11.6%) events of pathological fractures without cord

compression. No patient underwent prophylactic

surgery for bone metastasis. With regard to timing

of SRE development, 13 (10.9%) patients had SRE

as the initial presentation of metastatic prostate

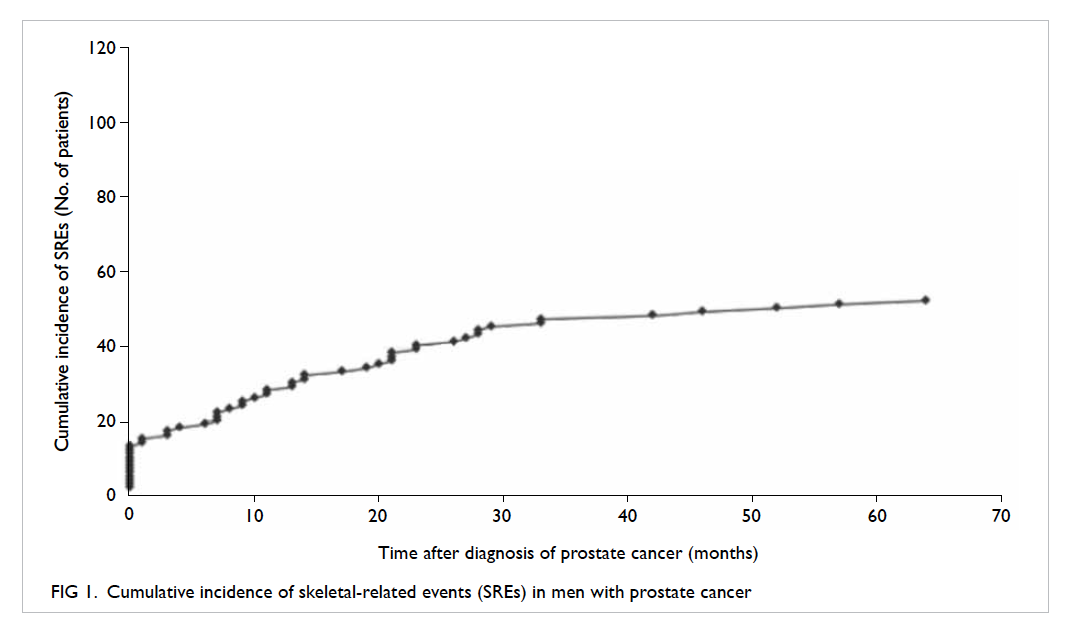

cancer. The overall cumulative incidence of SREs at

1 year and 5 years of diagnosis was 23.5% and 42.9%,

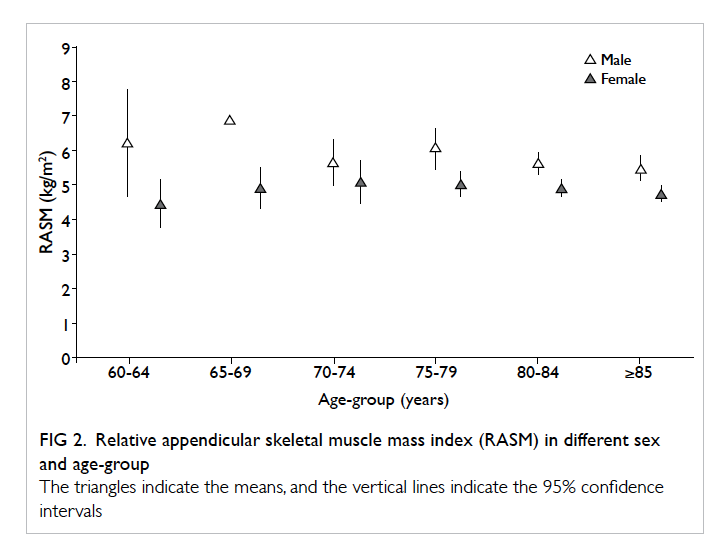

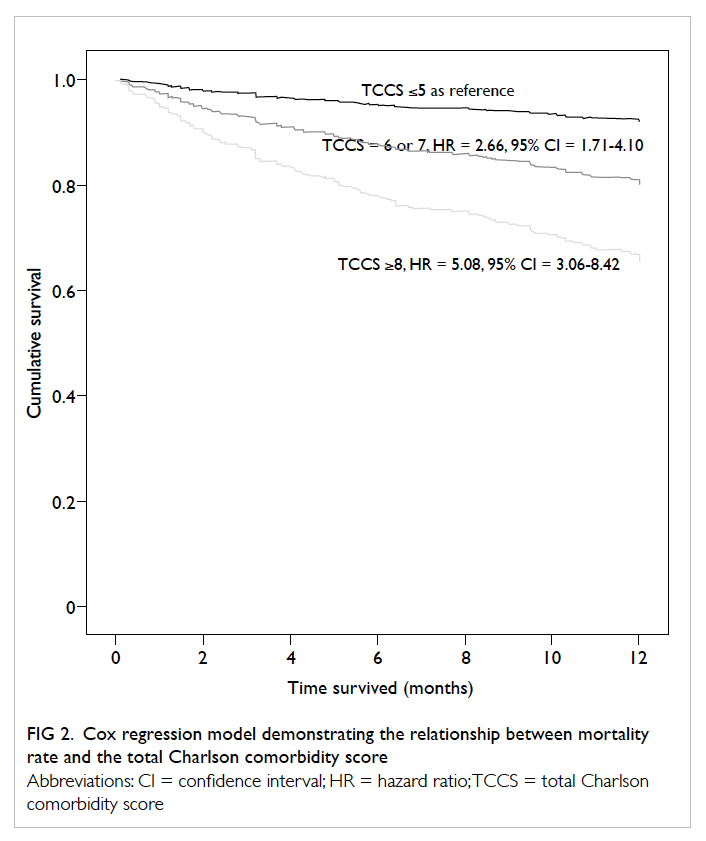

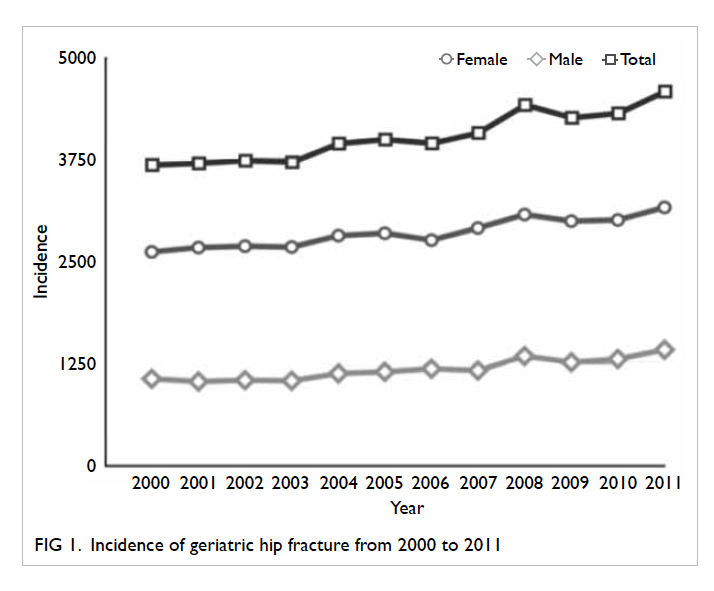

respectively (Fig 1).

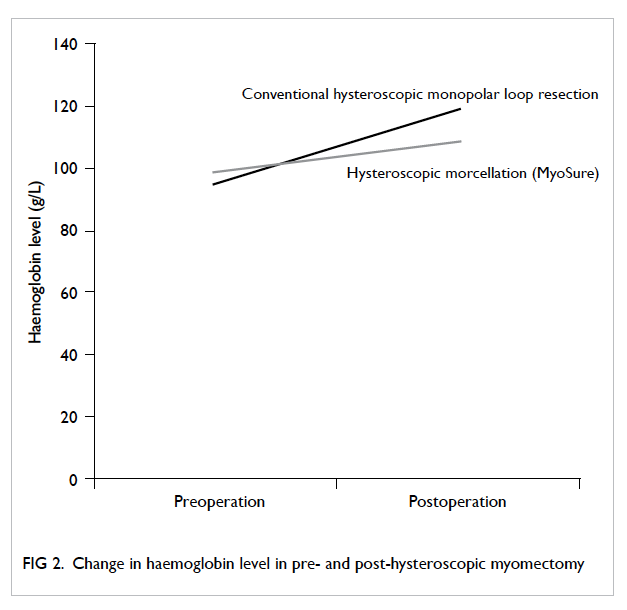

Castration-resistant status and survival

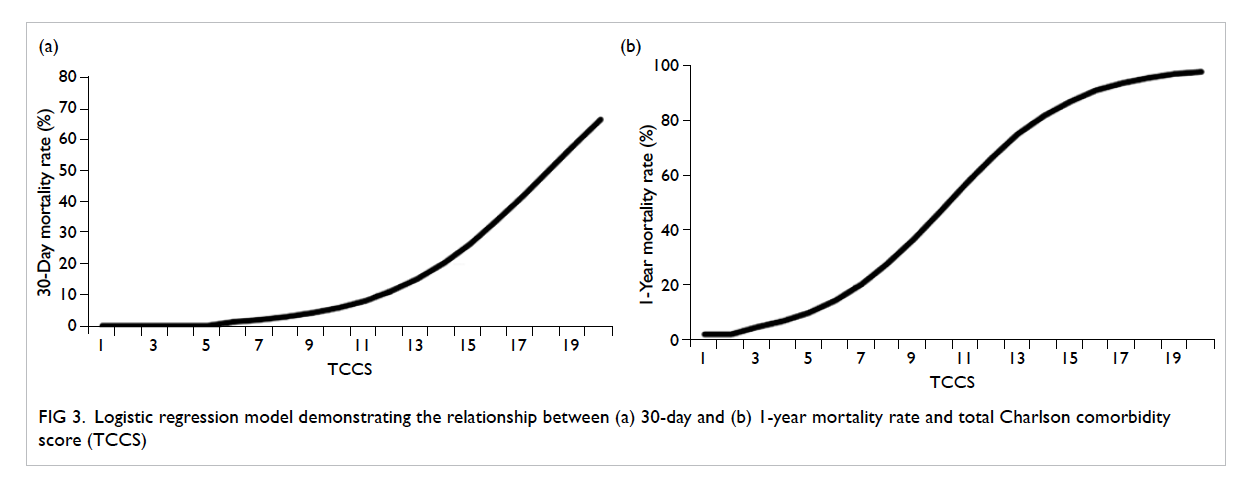

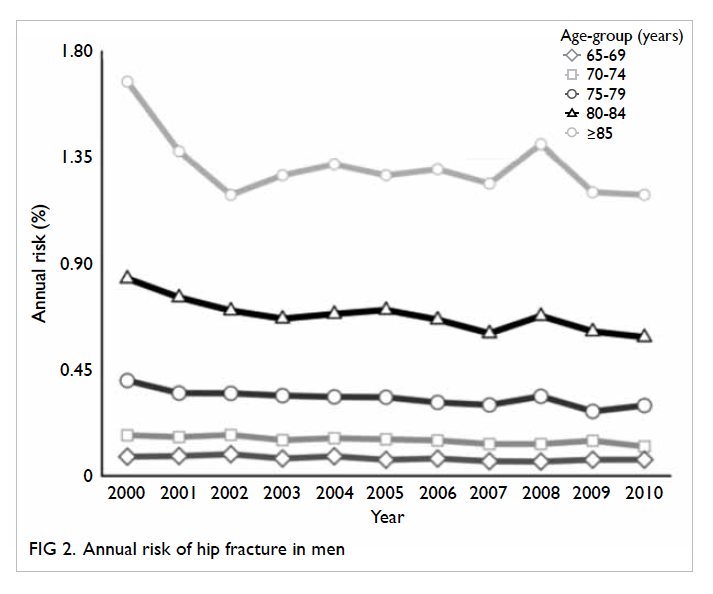

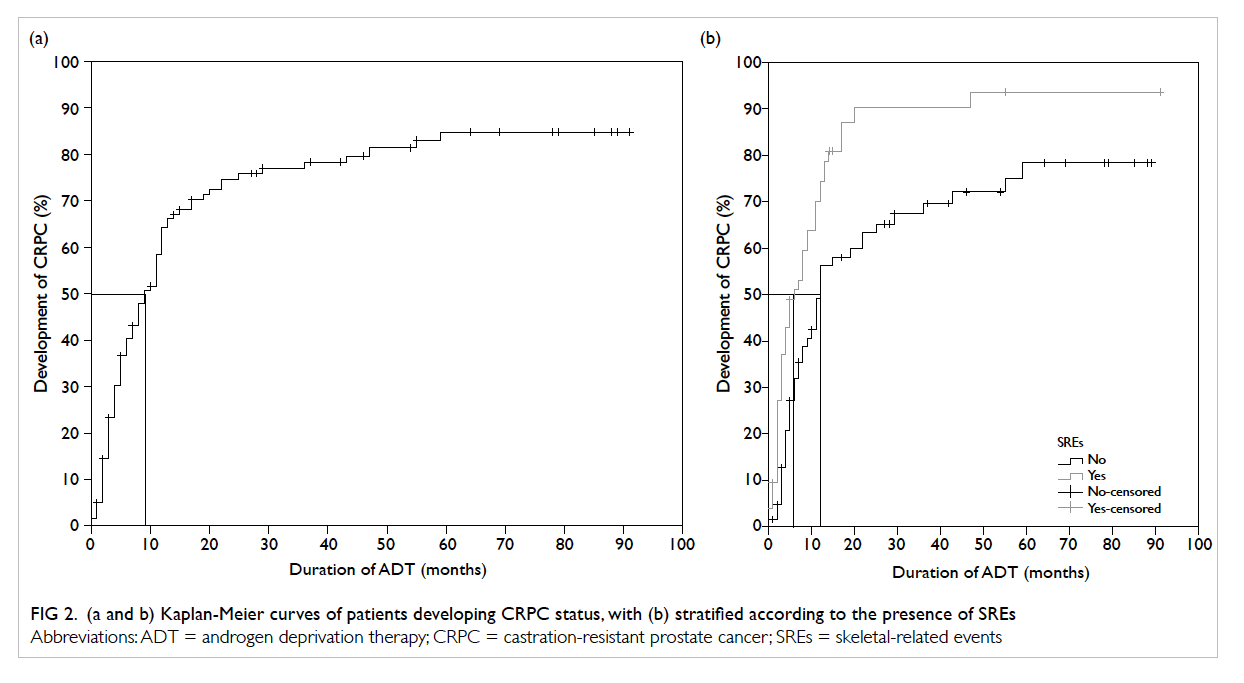

The median time required to develop CRPC status

from the start of ADT was 9 months (Fig 2a). When stratified according to the presence of SREs, the

median time to CRPC status from ADT initiation

was significantly shorter in patients with SREs than

in those without (6 vs 12 months, log-rank test,

P=0.001; Fig 2b).

Figure 2. (a and b) Kaplan-Meier curves of patients developing CRPC status, with (b) stratified according to the presence of SREs

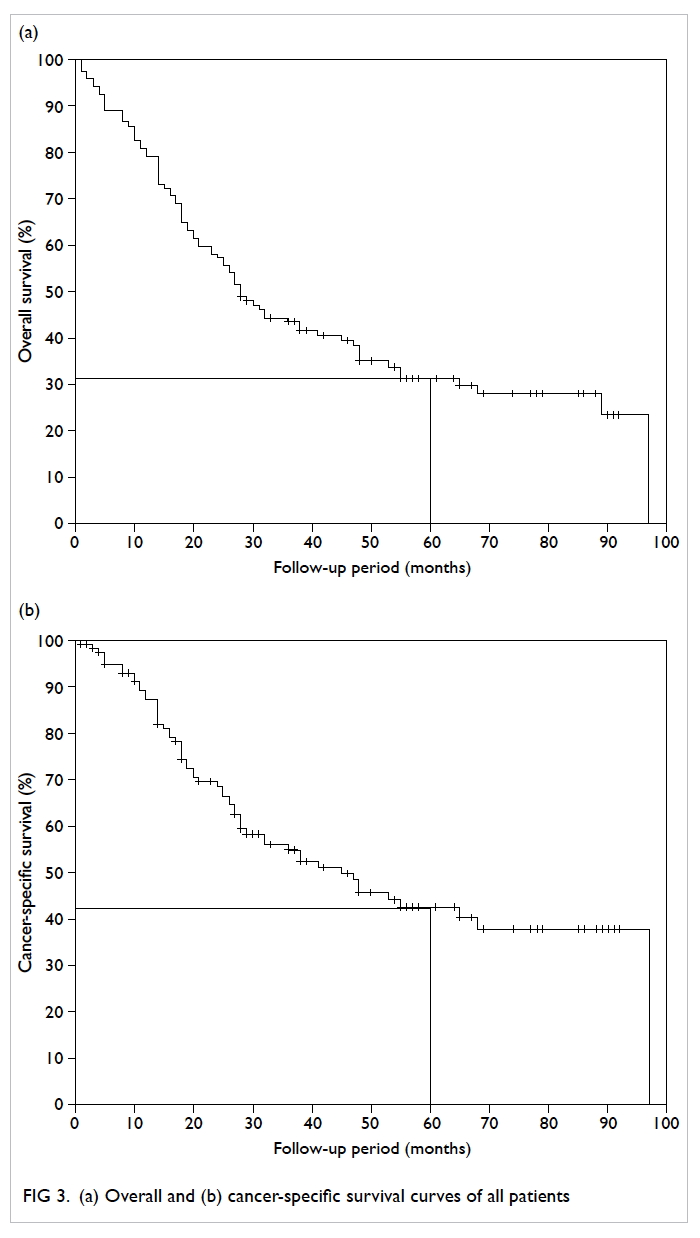

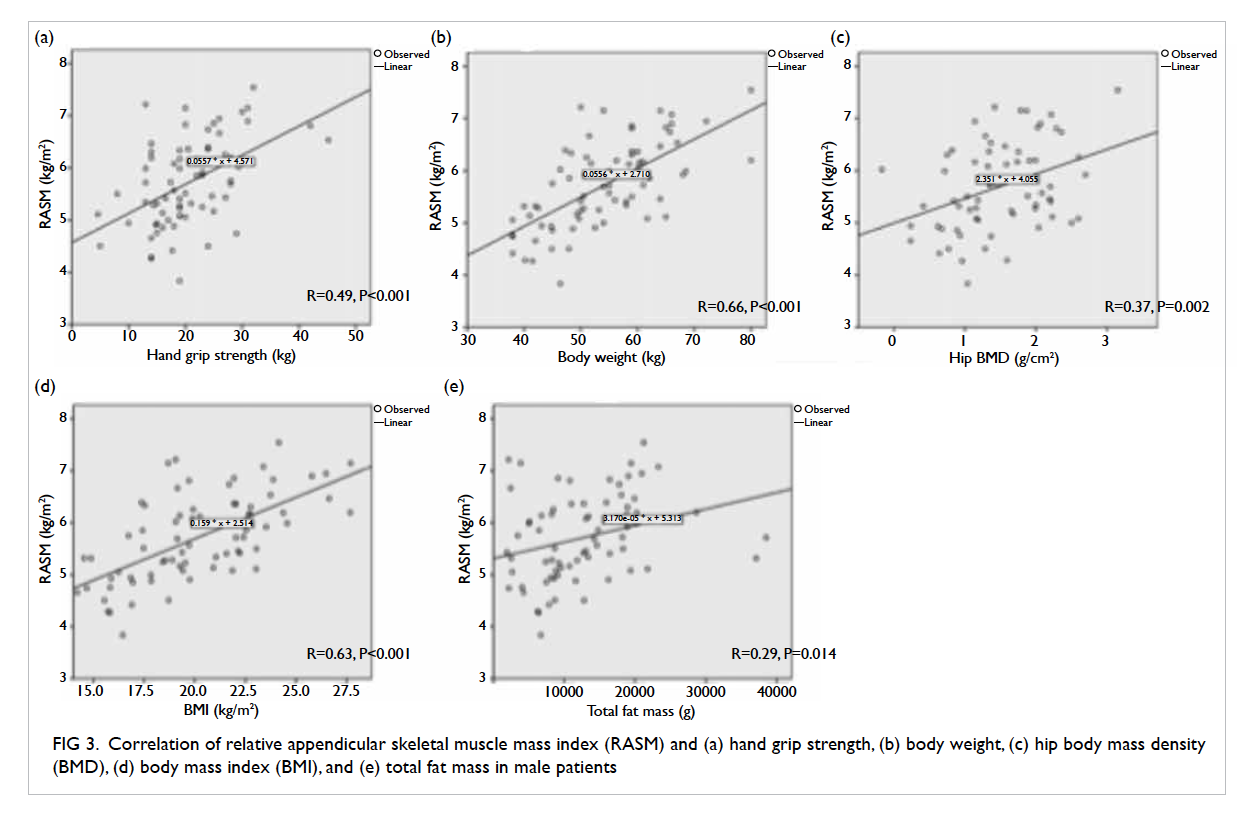

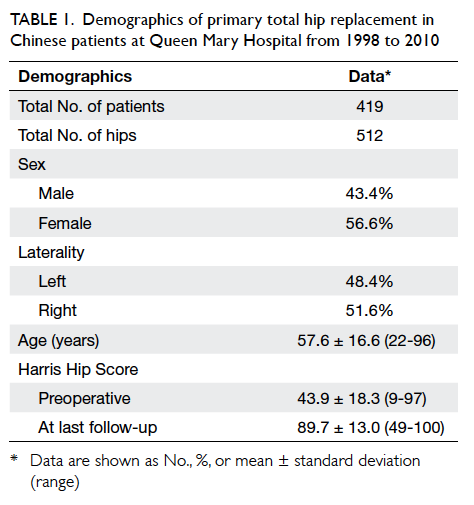

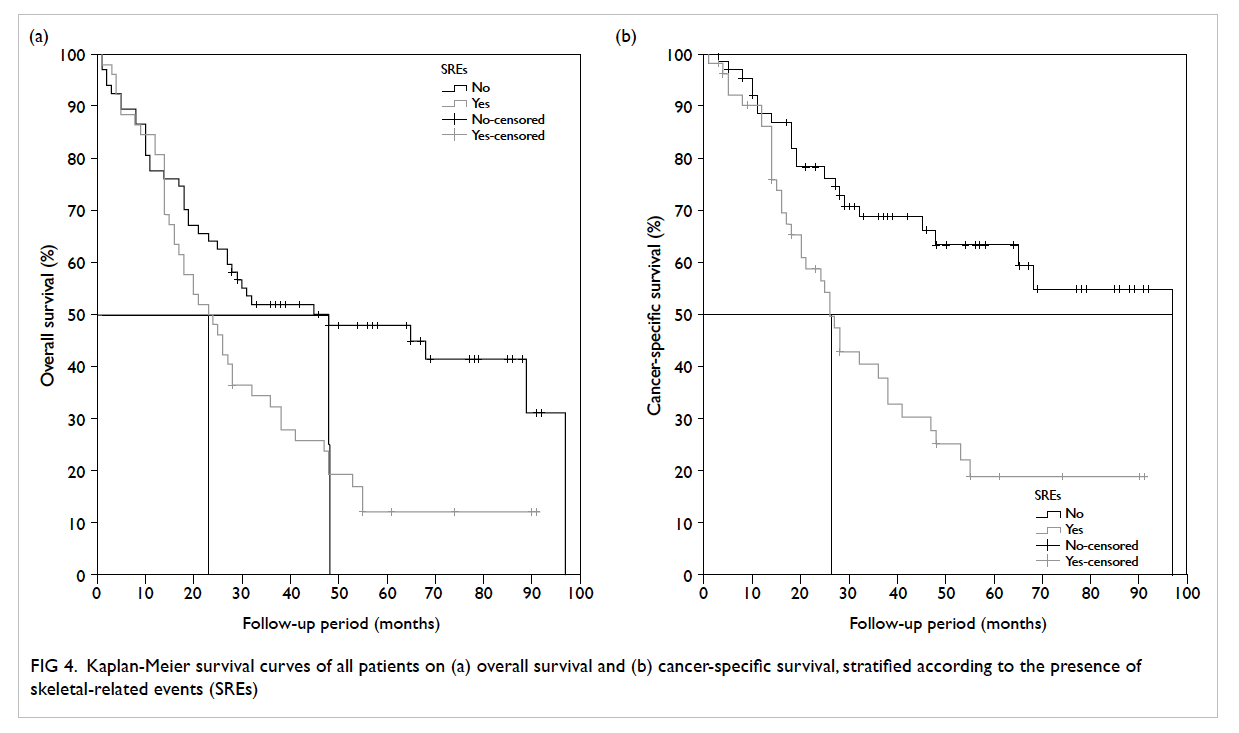

The actuarial overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific

survival (CSS) curves are shown in Figure 3. The 5-year actuarial OS and CSS was 32% and 43%, respectively. Among men without SREs, 38 (56.7%) patients died, compared with 44 (84.6%) patients

in the SRE group. When stratified according to presence of SREs (Fig 4), the median OS and CSS for patients with SREs were significantly shorter than

that for patients without SREs (log-rank test: 23 vs

48 months, P=0.003 and 26 vs 97 months, P<0.001,

respectively).

Figure 4. Kaplan-Meier survival curves of all patients on (a) overall survival and (b) cancer-specific survival, stratified according to the presence of skeletal-related events (SREs)

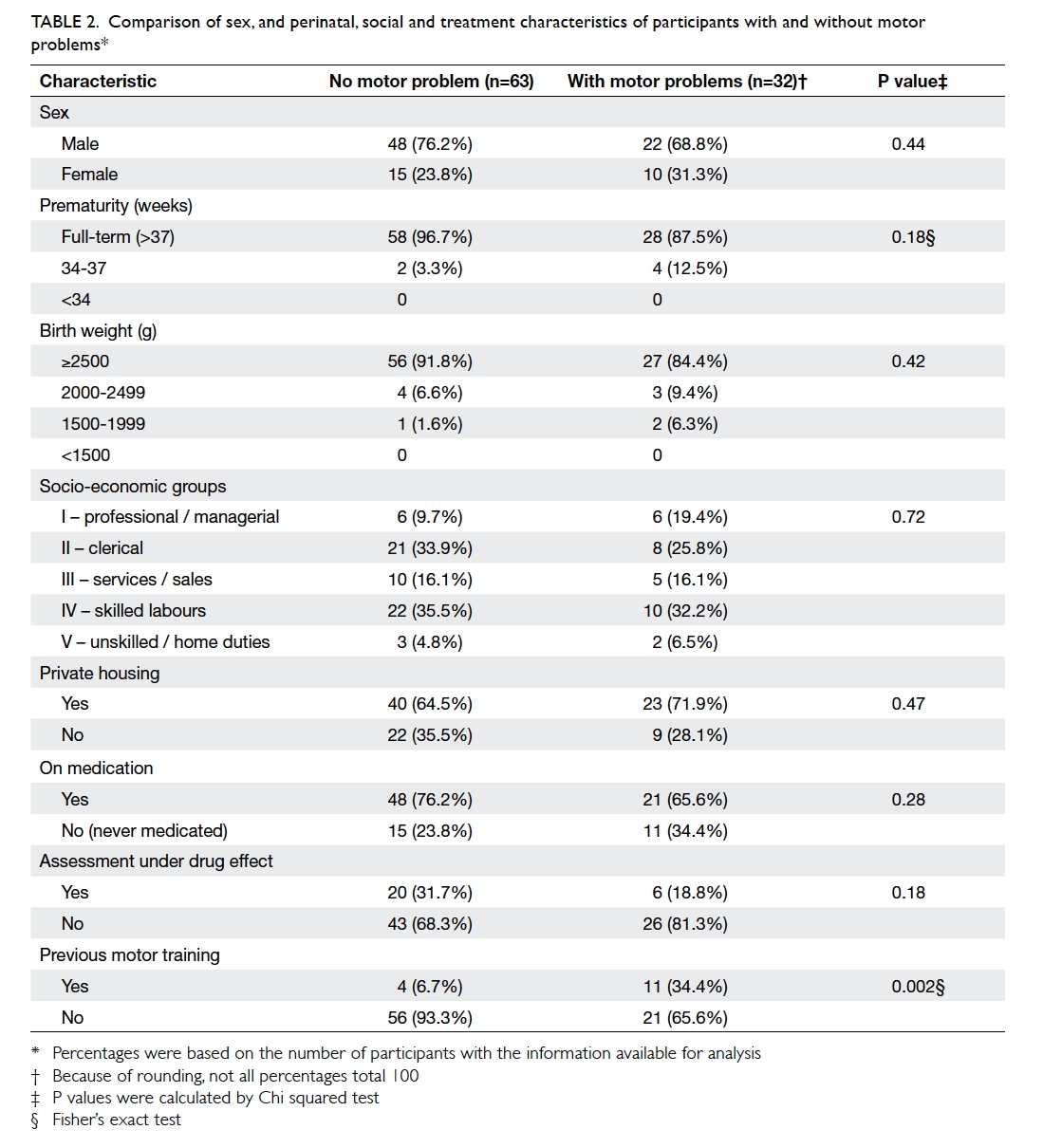

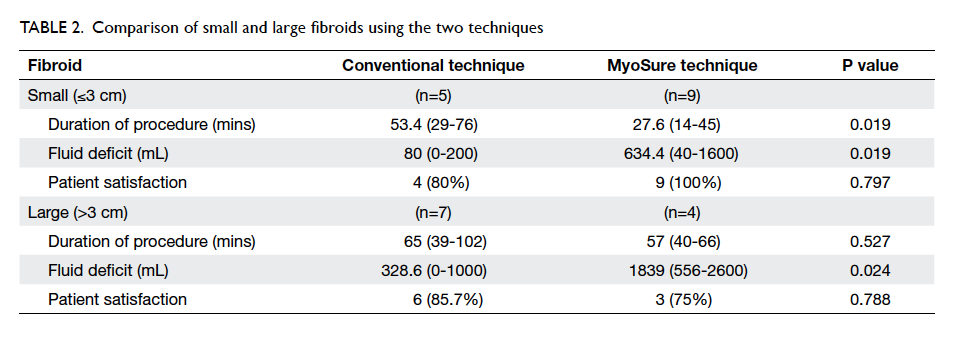

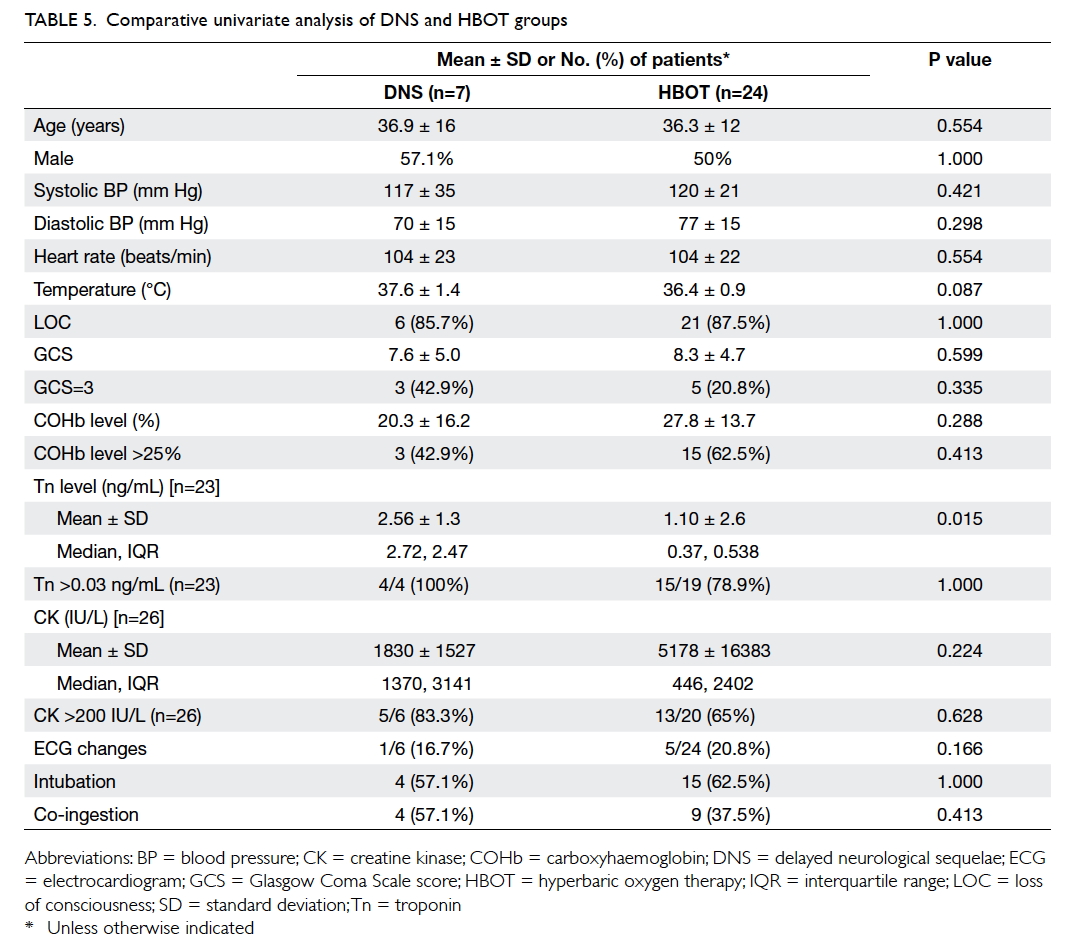

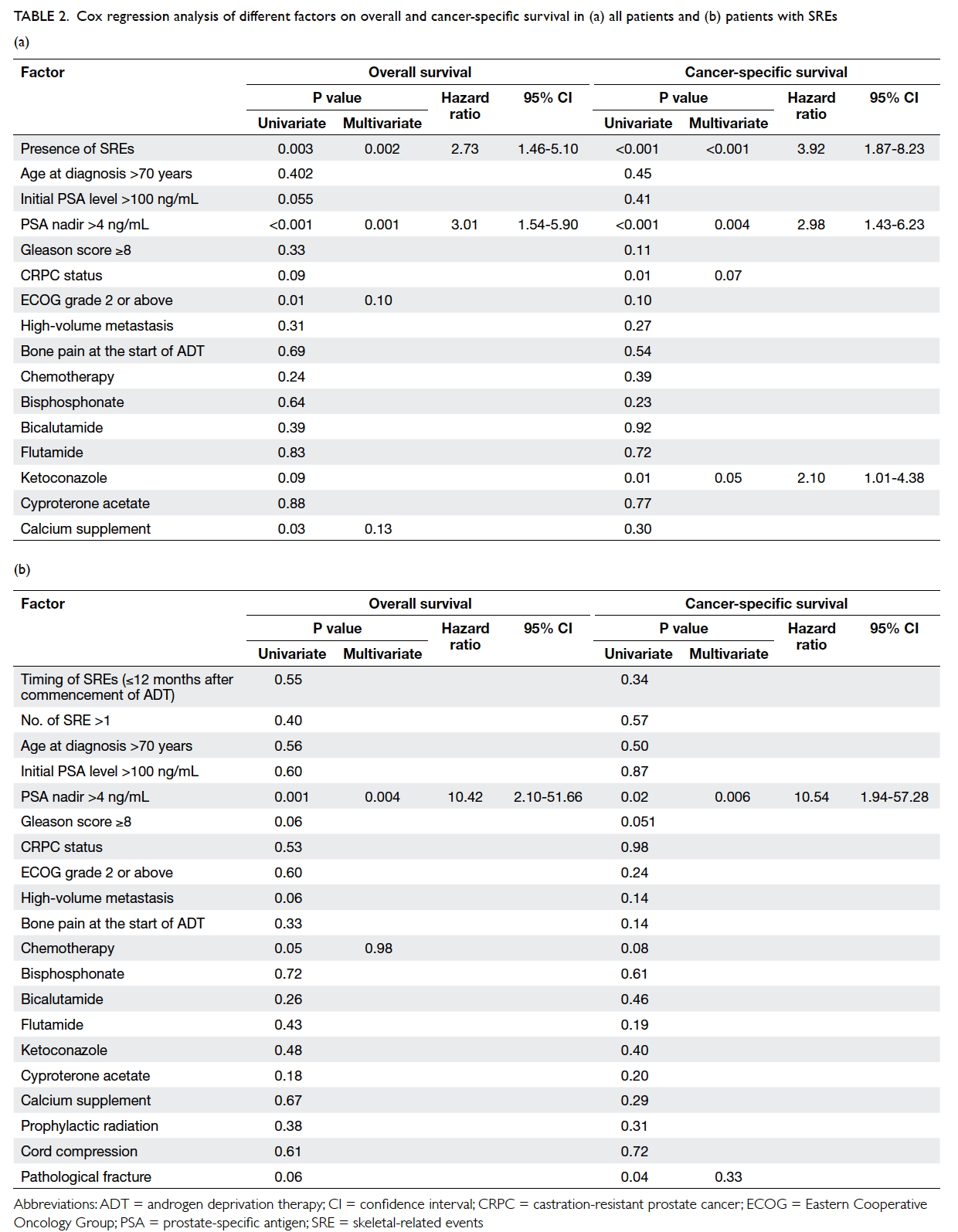

Risk factors for survival

Various possible factors that could affect survival

were analysed (Table 2a). All treatments for prostate cancer received both before and after SRE were

included. Univariate analysis revealed that in terms

of OS, presence of SREs (P=0.003), PSA nadir of >4

ng/mL (P<0.001), ECOG grade 2 or above (P=0.01),

and calcium supplement (P=0.03) were significant

risk factors. On multivariate analysis, only the

presence of SREs and PSA nadir of >4 ng/mL

remained statistically significant, with hazard ratio

(HR) of 2.73 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.46-5.10; P=0.002) and 3.01 (95% CI, 1.54-5.90; P=0.001),

respectively. In terms of CSS, presence of SREs

(P<0.001), PSA nadir of >4 ng/mL (P=0.004), and

ketoconazole therapy (P=0.05) remained significant risk

factors on both univariate and multivariate analyses.

The HR for the presence of SREs, PSA nadir of >4

ng/mL, and ketoconazole therapy was 3.92 (95% CI, 1.87-8.23; P<0.001), 2.98 (95% CI, 1.43-6.23;

P=0.004), and 2.10 (95% CI, 1.01-4.38; P=0.05), respectively.

Table 2. Cox regression analysis of different factors on overall and cancer-specific survival in (a) all patients and (b) patients with SREs

The median survival period after occurrence

of SRE was 11.5 months. A post-hoc analysis for OS

and CSS after SRE revealed PSA nadir of >4 ng/mL

as the only independent predictor for survival after

SRE in both univariate and multivariate analyses,

with HR of 10.42 (95% CI, 2.10-51.66; P=0.004) and

10.54 (95% CI, 1.94-57.28; P=0.006), respectively

(Table 2b).

Discussion

The importance of SREs in survival of patients with

prostate cancer with different disease stage and

treatments was studied10 11 12 but not specifically in

patients with metastatic prostate cancer prescribed

ADT. This group of patients was selected because

patients with metastatic prostate cancer are at risk of

developing SREs.11 In addition, ADT is the standard

first-line treatment for metastatic prostate cancer.12

It has been proven to provide a clear benefit in terms

of preventing SREs.13 Focusing on patients who are

prescribed ADT can ensure that the effect of ADT in

preventing SREs is balanced out during analysis. A

study by Oefelein et al9 showed that skeletal fractures

negatively correlate with OS in men with prostate

cancer prescribed ADT, but it included patients with

localised disease and all kinds of fracture including

osteoporotic fractures. Berruti et al4 reported the

incidence of skeletal complications in patients with

CRPC and bone metastasis, but failed to demonstrate

any difference in survival between patients with and

without skeletal complications. Multivariate analysis

was not performed on survival either. Daniell et al14 15 reported eight fractures in 49 patients with prostate cancer at various times following orchiectomy but

did not take into account the preventive effect of

ADT in SREs.13 In our study, patients with SREs

had much worse OS and CSS when compared with

those without SREs (23 vs 48 months and 26 vs 97

months, respectively), and remained significantly

so after multivariate Cox regression analysis. To

our knowledge, this is the first reported study to

investigate the impact of SREs on survival in this

homogeneous group of patients.

The baseline characteristics were similar

between patients with or without SREs except that

those with SREs were slightly younger at diagnosis

(73.1 vs 76.3 years; P=0.04). This, however, does

not affect data interpretation since age at diagnosis

was not a significant factor in subsequent analyses

for both OS and CSS. In our targeted group of

patients with metastatic prostate cancer prescribed

ADT, the presence of SREs was first shown to be an

independent predictive factor for OS and CSS with

a notable HR of 2.73 and 3.92 respectively, taking

into account baseline cancer characteristics, ECOG

performance status, development of CRPC status,

and different treatments received. In addition, PSA

nadir was found to be another predictive factor

for OS and CSS. This finding has been reported in

previous studies16 although most included patients

who were heterogeneous in terms of clinical stage

of prostate cancer. Kitagawa et al16 showed that

PSA nadir of >4 ng/mL was associated with HR of

5.22 (95% CI, 2.757-9.89; P<0.001) in OS in patients

with prostate cancer. The cohort, however, included

patients with either locally advanced non-metastatic

disease or metastatic disease. Park et al17 reported

that a higher PSA nadir level correlated with shorter

CSS. Similar to the previous study,16 patients with

lymph node metastasis were also included. In

another retrospective study,18 a high PSA nadir level

was shown to be associated with shorter OS in a

homogeneous group of patients with metastatic

prostate cancer prescribed ADT. Nonetheless only

87 patients were included in the study. In our study,

in patients who developed SREs, PSA nadir was the

only predictive factor for both OS and CSS with HR

of 10.42 and 10.54, respectively. This is previously

unreported.

Various treatments have been proven to improve

OS in patients with metastatic prostate cancer,

including docetaxel,19 cabazitaxel,20 abiraterone,21 22 23

sipuleucel-T,24 and enzalutamide.25 26 Various bone-modulating

agents have also been studied for patients

with bone metastasis. Bisphosphonate therapy has

been shown to improve bone mineral density and

quality of life,27 28 and reduce the incidence of SREs in patients with metastatic CRPC in a randomised

controlled trial (RCT), although there was no proven

survival benefit.6 The receptor activator for nuclear

factor κB ligand (RANKL) inhibitor denosumab is

another bone-modulating agent proven to reduce

the incidence of SREs in metastatic CRPC patients

but also without survival benefit.29 30 Radium-223,

a bone-seeking calcium-mimicking alpha emitter,

was shown in a RCT31 to not only delay first

symptomatic SRE, but also improve OS. Therefore,

when investigating the incidence of SRE and survival

in these groups of patients, the aforementioned

treatments have to be taken into account. In our

study, treatments received by patients without SREs

and in patients prior to development of SREs were

statistically similar (Table 1). The number of patients prescribed chemotherapy or novel hormonal agents

was relatively small in our series. Sipuleucel-T,

enzalutamide, and radium-223 were not available

in this locality during the study period. Denosumab

and abiraterone therapies were used by only two

patients in each group as these medications were

not subsidised by the local government and were

not affordable for many patients. Docetaxel has

been shown to improve bone pain and OS in a phase

III RCT.19 After development of SREs, six more

patients received chemotherapy in our series. All

but one patient received docetaxel. The remaining

patient received estramustine and etoposide before

development of SREs. The fact that all patients

prescribed docetaxel were in the SRE group suggests

that its potential benefit in improving OS has been

offset by SREs and so this is not a confounding factor

in our study.

The overall prevalence of bisphosphonate

therapy was low (17%). Nine patients received

bisphosphonate therapy only after development of

SREs. In fact, in patients receiving bisphosphonate

therapy, two out of seven patients without SREs

and six out of 13 patients with SREs only received

one dose of bisphosphonate due to various

reasons, including side-effects of the medication,

affordability, and early mortality after medication.

With the heterogeneous timing of start and duration

of therapy, we cannot accurately comment on the

benefit of bisphosphonate in our series. No further

patient received RANKL inhibitor or abiraterone

after development of SREs.

Since the pre-chemotherapy era, the concept of

complete androgen blockade with classic hormonal

manipulation by both steroidal anti-androgen, such

as cyproterone acetate,32 and non-steroidal anti-androgen

(such as bicalutamide,33 flutamide,34 and

nilutamide35) has been widely adopted when patients

develop CRPC status. This practice remains in use

in this locality despite the fact that no associated

survival benefit has ever been reported12 due to the

side-effects and availabilities of aforementioned

novel treatments for CRPC. Ketoconazole, a broad-spectrum

imidazole antifungal agent, was previously

the hormonal treatment of choice after anti-androgen

withdrawal for complete androgen blockade.35

It works by preventing adrenal steroidogenesis

with inhibition of the enzyme cytochrome P450

14 alpha-demethylase.36 Bicalutamide, flutamide,

cyproterone acetate, and ketoconazole were used in

our centre for hormonal manipulation. Interestingly,

ketoconazole use appeared to have a deleterious

effect on CSS even with multivariate Cox regression

in our study. This result contradicts that of a phase

III RCT35 which showed positive PSA and objective

response but no survival benefit or harm. As our

study was retrospective in nature, the implication of

ketoconazole use is doubtful based on the results of

this study and requires further evaluation.

With a median follow-up of 28 months, the

incidence of SREs in men with metastatic prostate

cancer was high (43.7%) and is comparable with

43.6% reported from the Danish group population-based

cohort study with similar follow-up period.11

The median time to CRPC status from first ADT

was 9 months, which is 5.7 months shorter than the

control arm of the CHAARTED trial.37 This may

be explained by the fact that the CHAARTED trial

included patients prescribed ADT for less than 24

months but those with disease progression within 12

months were excluded.

We obtained local data of the natural history

of metastatic prostate cancer with or without SREs

and the impact of SREs on survival. A PSA nadir

of >4 ng/mL was an independent poor prognostic

factor for OS and CSS after development of SREs.

Its clinical use in terms of predicting prognosis

and patient counselling is highly feasible. Based

on our results, prevention of SREs in patients with

metastatic prostate cancer may translate to longer

survival. Nonetheless most bone-targeting therapies,

including bisphosphonate therapy and RANKL

inhibitors, have failed to demonstrate survival benefit

even though they prevent SREs.6 30 34 38 Radium-223

appears to hold promise as it delays symptomatic SREs by 5.8 months and improves OS by 3.8 months

in metastatic prostate cancer patients.31 Further

studies are needed in this field.

There are several limitations in this study. This

was a retrospective study with small sample size so

statistical power is limited. There are even fewer

patients in post-hoc analysis. The data collected

may not accurately reflect the condition of patients

because the follow-up protocol was not standardised.

Furthermore, the data abstraction process was not

blinded. For better presentation of data, several

factors such as PSA nadir, initial PSA, and age at

diagnosis were analysed as categorical data. This

could lead to information bias. The definition of

CRPC was less stringent than that suggested from

international guidelines12 because testosterone level

and follow-up imaging such as bone scans were

not routinely performed due to limited resources.

Potential confounding factors for survival such as

smoking and co-morbidity were also not included in

the study and may have affected the validity of the

results. The small number of patients prescribed

novel treatments or bone-modulating agents did

not allow a comprehensive understanding of their

influence on SRE occurrence. Further prospective

trials with a large cohort size are necessary.

Conclusions

Skeletal-related events were common in men with

metastatic prostate cancer and were first shown by

this study to be an independent prognostic factor

of OS and CSS in patients with metastatic prostate

cancer prescribed ADT. A PSA nadir of >4 ng/mL is

an independent poor prognostic factor for OS and

CSS following development of SREs.

References

1. Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, Jemal A. Cancer statistics,

2011: the impact of eliminating socioeconomic and racial

disparities on premature cancer deaths. CA Cancer J Clin

2011;61:212-36. Crossref

2. Hong Kong Cancer Registry 2012. Available from:

http://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/Summary%20of%20CanStat%202012.pdf. Accessed 6 Oct 2015.

3. Mullan RJ, Jacobsen SJ, Bergstralh EJ, et al. Decline in the

overall incidence of regional-distant prostate cancer in

Olmsted County, MN, 1980-2000. BJU Int 2005;95:951-5. Crossref

4. Berruti A, Dogliotti L, Bitossi R, et al. Incidence of skeletal

complications in patients with bone metastatic prostate

cancer and hormone refractory disease: predictive role

of bone resorption and formation markers evaluated at

baseline. J Urol 2000;164:1248-53. Crossref

5. Saad F, Gleason DM, Murray R, et al. A randomized,

placebo-controlled trial of zoledronic acid in patients with

hormone-refractory metastatic prostate carcinoma. J Natl

Cancer Inst 2002;94:1458-68. Crossref

6. Saad F, Gleason DM, Murray R, et al. Long-term efficacy of

zoledronic acid for the prevention of skeletal complications

in patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate

cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004;96:879-82. Crossref

7. Galasko CS. Skeletal metastases. Clin Orthop Relat Res

1986;210:18-30. Crossref

8. Logothetis CJ, Navone NM, Lin SH. Understanding the

biology of bone metastases: key to the effective treatment

of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2008;14:1599-602. Crossref

9. Oefelein MG, Ricchiuti V, Conrad W, Resnick MI. Skeletal

fractures negatively correlate with overall survival in men

with prostate cancer. J Urol 2002;168:1005-7. Crossref

10. Saad F, Lipton A, Cook R, Chen YM, Smith M, Coleman

R. Pathologic fractures correlate with reduced survival

in patients with malignant bone disease. Cancer

2007;110:1860-7. Crossref

11. Nørgaard M, Jensen AØ, Jacobsen JB, Cetin K, Fryzek JP, Sørensen HT. Skeletal related events, bone metastasis and

survival of prostate cancer: a population based cohort

study in Denmark (1999 to 2007). J Urol 2010;184:162-7. Crossref

12. Mottet N, Bastian PJ, Bellmunt J, et al. European

Association of Urology Guidelines on Prostate Cancer

2014. Available from: http://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/1607-Prostate-Cancer_LRV3.pdf. Accessed 6 Oct

2015.

13. Nair B, Wilt T, MacDonald R, Rutks I. Early versus

deferred androgen suppression in the treatment of

advanced prostatic cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2002;(1):CD003506.

14. Daniell HW. Osteoporosis after orchiectomy for prostate

cancer. J Urol 1997;157:439-44. Crossref

15. Daniell HW, Dunn SR, Ferguson DW, Lomas G,

Niazi Z, Stratte PT. Progressive osteoporosis during

androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J Urol

2000;163:181-6. Crossref

16. Kitagawa Y, Ueno S, Izumi K, et al. Nadir prostate-specific

antigen (PSA) level and time to PSA nadir following primary

androgen deprivation therapy as independent prognostic

factors in a Japanese large-scale prospective cohort study

(J-CaP). J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2014;140:673-9. Crossref

17. Park YH, Hwang IS, Jeong CW, Kim HH, Lee SE, Kwak

C. Prostate specific antigen half-time and prostate

specific antigen doubling time as predictors of response

to androgen deprivation therapy for metastatic prostate

cancer. J Urol 2009;181:2520-4; discussion 2525. Crossref

18. Sasaki T, Onishi T, Hoshina A. Nadir PSA level and time

to PSA nadir following primary androgen deprivation

therapy are the early survival predictors for prostate cancer

patients with bone metastasis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic

Dis 2011;14:248-52. Crossref

19. Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, et al. Docetaxel plus

prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced

prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1502-12. Crossref

20. de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, et al. Prednisone

plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant

prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel

treatment: a randomised open-label trial. Lancet

2010;376:1147-54. Crossref

21. Ryan CJ, Smith MR, de Bono JS, et al. Abiraterone in

metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherapy.

N Engl J Med 2013;368:138-48. Crossref

22. de Bono JS, Logothetis CJ, Molina A, et al. Abiraterone and

increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J

Med 2011;364:1995-2005. Crossref

23. Fizazi K, Scher HI, Molina A, et al. Abiraterone acetate

for treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate

cancer: final overall survival analysis of the COU-AA-301

randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3

study. Lancet Oncol 2012;10:983-92. Crossref

24. Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, et al. Sipuleucel-T

immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N

Engl J Med 2010;363:411-22. Crossref

25. Beer TM, Armstrong AJ, Rathkopf DE, et al. Enzalutamide

in metastatic prostate cancer before chemotherapy. N Engl

J Med 2014;371:424-33. Crossref

26. Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, et al. Increased survival with

enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N

Engl J Med 2012;367:1187-97. Crossref

27. Saad F. Maintaining bone health throughout the continuum

of care for prostate cancer. In: Progress in bone cancer

research. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers; 2006.

28. Smith MR. Bisphosphonates to prevent osteoporosis in

men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate

cancer. Drugs Aging 2003;20:175-83. Crossref

29. Smith MR, Egerdie B, Hernández Toriz N, et al. Denosumab

in men receiving androgen-deprivation therapy for

prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2009;361:745-55. Crossref

30. Fizazi K, Carducci M, Smith M, et al. Denosumab versus

zoledronic acid for treatment of bone metastases in men

with castration-resistant prostate cancer: a randomised,

double-blind study. Lancet 2011;377:813-22. Crossref

31. Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, et al. Alpha emitter

radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N

Engl J Med 2013;369:213-23. Crossref

32. Goldenberg SL, Bruchovsky N. Use of cyproterone acetate

in prostate cancer. Urol Clin North Am 1991;18:111-22.

33. Scher HI, Liebertz C, Kelly WK, et al. Bicalutamide for

advanced prostate cancer: the natural versus treated

history of disease. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:2928-38.

34. Crawford ED, Eisenberger MA, McLeod DG, et al. A

controlled trial of leuprolide with and without flutamide in

prostatic carcinoma. N Engl J Med 1989;321:419-24. Crossref

35. Small EJ, Halabi S, Dawson NA, et al. Antiandrogen

withdrawal alone or in combination with ketoconazole in

androgen-independent prostate cancer patients: a phase

III trial (CALGB 9583). J Clin Oncol 2004;22:1025-33. Crossref

36. Loose DS, Kan PB, Hirst MA, Marcus RA, Feldman D.

Ketoconazole blocks adrenal steroidogenesis by inhibiting

cytochrome P450-dependent enzymes. J Clin Invest

1983;71:1495-9. Crossref

37. Sweeney CJ, Chen YH, Carducci M, et al. Chemohormonal

therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;373:737-46. Crossref

38. Dole EJ, Holdsworth MT. Nilutamide: an antiandrogen

for the treatment of prostate cancer. Ann Pharmacother

1997;31:65-75.