Hong Kong Med J 2015 Apr;21(2):136–42 | Epub 16 Jan 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144236

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Implementation of secondary stroke prevention protocol for ischaemic stroke patients in primary care

YK Choi, FHKCFP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)1; JH Han, MD, PhD1; Richard Li, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)2; Kenny Kung, FHKCFP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)3; Augustine Lam, FHKCFP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)4

1 Lek Yuen General Out-patient Clinic, Department of Family Medicine, New Territories East Cluster, Hong Kong

2 Department of Medicine, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong

3 Department of Family Medicine and Primary Care, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

4 Department of Family Medicine, New Territories East Cluster, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr YK Choi (yuekwan@hotmail.com)

Abstract

Objective: To investigate the effectiveness of a secondary stroke prevention protocol in the general out-patient clinic.

Design: Cohort study with pre- and post-intervention

comparisons.

Setting: Two general out-patient clinics in Hong

Kong.

Patients: Ischaemic stroke patients who had long-term

follow-up in two clinics were recruited. The

patients of one clinic received the intervention

(intervention group) and the patients of the second

clinic did not receive the intervention (control

group). The recruitment period lasted for 6 months

from 1 September 2008 to 28 February 2009. The

pre-intervention phase data collection started within

this 6-month period. The protocol implementation

started at the intervention clinic on 1 April 2009.

The post-intervention phase data collection started

9 months after the protocol implementation, and ran

for 6 months from 1 January 2010 to 30 June 2010.

Main outcome measures: Clinical data before and

after the intervention, including blood pressure,

glycated haemoglobin level, low-density lipoprotein level and

prescription pattern, were compared between the

two groups to see whether there was enhancement

of secondary stroke management.

Results: A total of 328 patients were recruited into the intervention group and 249 into the control group; data of 256 and 210 patients from these groups were analysed, respectively.

After intervention, there were significant reductions in mean (± standard deviation) systolic

blood pressure (135.2 ± 17.5 mm Hg to 127.7 ±

12.2 mm Hg), glycated haemoglobin level (7.2 ± 1.0% to

6.5 ± 0.8%), and low-density lipoprotein level (3.4 ± 0.8

mmol/L to 2.8 ± 1.3 mmol/L) in the intervention

group (all P<0.01). There were no significant reductions in mean

systolic blood pressure, glycated haemoglobin level, or

low-density lipoprotein level in the control group. There

was a significant increase in statin use (P<0.01) in

both clinics.

Conclusion: Through implementation of a clinic

protocol, the standard of care of secondary stroke

prevention for ischaemic stroke patients could be

improved in a general out-patient clinic.

New knowledge added by this

study

- A standard secondary stroke prevention protocol can significantly improve the control of cardiovascular risk factors in ischaemic stroke patients.

- Implementation of such a programme is effective and feasible in local primary care.

- This study supports more widespread use of a secondary stroke prevention programme in the setting of a general out-patient clinic.

Introduction

Stroke is the second commonest cause of death

worldwide1 and the fourth leading cause of death

in Hong Kong.2 Stroke is also the commonest cause

of permanent disability in adults. Patients with

stroke are at high risk for recurrent stroke and other

major vascular events. As the ageing population is

increasing in most developed countries, stroke will

remain a major burden to patients’ families and

carers, the health care system, and the community.

According to local data from Hong Kong,

cerebrovascular disease was the principal diagnosis

for about 26 500 in-patient discharges and deaths in

all hospitals and accounted for 7.5% of all deaths in

2012.3 The mortality rate was significantly higher in

patients with stroke recurrence than in those without.4 5 Prevention of recurrent stroke

offers great potential for reducing the burden of this

disease.

Over 80% of all strokes are ischaemic stroke.

There are effective strategies for secondary

prevention of ischaemic stroke, which are

summarised as follows6:

(1) Modification of lifestyle risk factors (smoking,

alcohol consumption, obesity, physical

inactivity).

(2) Modification of vascular risk factors

(hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, diabetes).

(3) Antiplatelet therapy for non-cardioembolic

ischaemic stroke.

(4) Anticoagulation for cardioembolic stroke.

(5) Intervention for symptomatic carotid stenosis.

As stroke patients need lifelong monitoring

and control of risk factors, family physicians play the

most important role in providing secondary stroke

prevention care. However, despite the availability

of evidence-based guidelines, studies show that

adherence to these preventive strategies by physicians

is poor.7 8 9 10 11 Local Hong Kong data about secondary

stroke prevention in primary care are largely lacking.

This study aimed to review the clinical effectiveness

of a secondary stroke prevention programme in a

general out-patient clinic (GOPC).

Methods

This was a cohort study of pre- and post-intervention

comparison between patients receiving or not

receiving the intervention to ascertain the effect of a

secondary stroke prevention programme on clinical

outcomes.

Clinic setting

The Lek Yuen GOPC was selected as the intervention

site where the secondary stroke prevention

programme was implemented. Another clinic, the

Ma On Shan GOPC, was selected as the control site,

where usual care was provided. Both clinics are large

public primary care clinics under the management

of the Department of Family Medicine of the New

Territories East Cluster of the Hospital Authority.

Both clinics are accredited Family Medicine

Training Centres with similar service throughput

annually, covering a population of around 600 000

and providing approximately 30 000 attendances

monthly.

Most of the stroke patients in the clinics are

referred from the public hospitals. The patients

usually have a history of minor stroke with good

functional recovery and are clinically stable.

Clinic protocol development and implementation

A protocol of secondary stroke prevention (Box)

was developed with reference to evidence-based

guidelines (mainly according to the American Heart

Association and American Stroke Association stroke

guidelines).12 13 14

Study design

The target population of the study was all the

ischaemic stroke patients with long-term follow-up

in the two clinics. The recruitment period lasted for 6

months from 1 September 2008 to 28 February 2009.

As the usual follow-up interval of long-term patients

is about 3 to 4 months, the 6-month recruitment

period included all stroke patients who have

regular follow-up. The pre-intervention phase data

collection started within this 6-month period. The

protocol implementation started at the intervention

clinic on 1 April 2009. The post-intervention phase

data collection started 9 months after the protocol

implementation, that is, for 6 months from 1 January

2010 to 30 June 2010.

Sampling

The clinical data were collected by reviewing the

medical records of all patients assigned with the

International Classification of Primary Care coding

of K90 (stroke/cerebrovascular accident) or K91

(cerebrovascular disease). Only those patients

diagnosed with ischaemic stroke and who had at

least two consecutive follow-up visits within the

recruitment period were included. Patients who had

a history of haemorrhagic stroke were excluded. In

order to exclude patients with sporadic follow-up,

only those patients with two consecutive follow-up

visits in the post-intervention phase were regarded

as eligible for data collection. Those patients

without two consecutive follow-up visits in the post-intervention

phase were classified as dropouts.

Protocol implementation

One month before initiation of the protocol, two

1-hour training sessions were arranged for medical

officers and nurses in the intervention clinic.

During the training sessions, the treatment goals

for secondary ischaemic stroke prevention and

the relevant clinical evidence were presented. The

workflow and applicability of the protocol were

also discussed. Medical officers were required to

have good documentation of all the lifestyle and

cardiovascular risk factors of the ischaemic stroke

patients and provide care according to the protocol.

Nurses were trained to be familiar with the treatment

goals and provide patient education and lifestyle

modification interventions in line with the doctors’

referrals. Allied health services such as a dietitian,

smoking cessation clinic, diabetes complication

screening programme, and patient empowerment

programmes for diabetic and hypertensive patients

were available in both the intervention and control

clinics. Doctors in the intervention clinic were

encouraged to refer appropriate patients to these

services. There was no additional consultation time

allocated to these patients. In order to monitor

progress, the electronic consultation notes were

reviewed monthly for each patient to assess

compliance with the protocol. If suboptimal care

was noted, an electronic reminder with appropriate

management advice was issued to the patient’s

electronic medical record. The consulting doctor

would then be able to provide the appropriate

management at the next follow-up. Throughout

the protocol implementation period, interim clinic

meetings were held quarterly to present the data for

protocol compliance with the medical and nursing

staff of the intervention clinic.

In the control clinic, no specific protocol was

applied. Medication prescription and adjustment

was based solely on the physicians’ discretion.

The drug formulary was the same in both clinics.

Statins were introduced to both clinic formularies

in July 2009. There were no training sessions for

doctors and nursing staff in the control clinic, and

no electronic reminders or interim meetings for

progress monitoring.

Data collection

Baseline characteristics on sex, age, chronic illness

status, chronic drug use, laboratory results, and blood

pressure (BP) values were extracted from the Clinical

Data Analysis and Reporting System. The latest

laboratory results and BP values within

the data collection period were taken as the study

data. Individual case records were also reviewed for

the following lifestyle parameters: smoking status,

alcohol consumption, body mass index (BMI), and

exercise and diet history.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using

the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

(Windows version 20.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL],

US). Continuous variables were expressed as mean

and standard deviation. Baseline comparisons were

made with the Student’s t test or the Chi squared test

as appropriate. The mean BP, glycated

haemoglobin (HbA1c) level, and low-density lipoprotein

(LDL) level before and after intervention were compared

by paired-samples t test in both the intervention and

control clinics.

Results

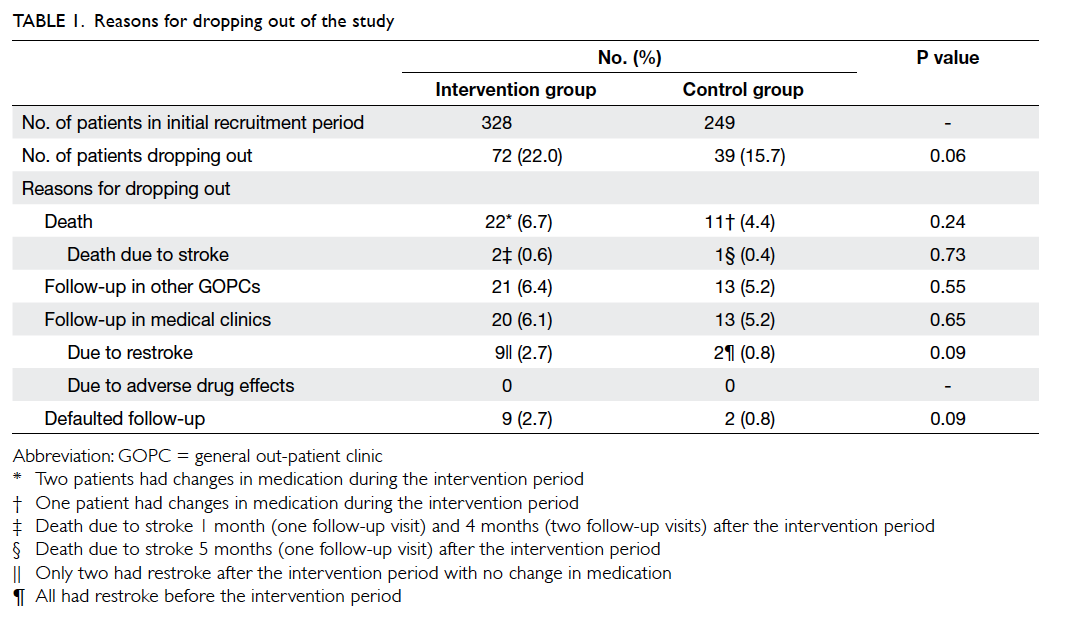

In the intervention clinic, 328 patients were

recruited to the intervention group and 72 dropped

out. In the control clinic, 249 were recruited to the

control group and 39 dropped out. The reasons for

dropping out are shown in Table 1. More patients in the intervention group than in the control group

dropped out due to restroke (9 vs 2, respectively)

and death (22 vs 11, respectively), but these were not

statistically significant due to the small number of

patients. In both the intervention and control groups,

most of the patients who died had no medication

changes during the intervention period (Table 1).

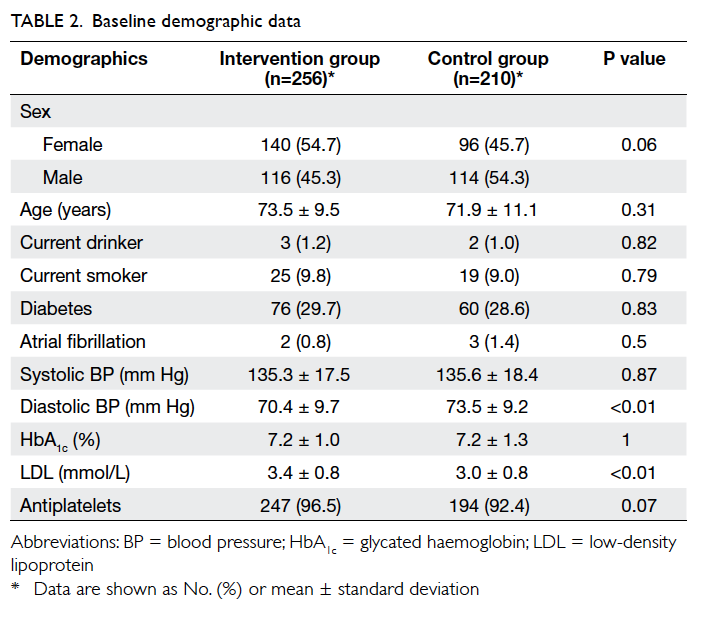

A total of 256 patients in the intervention

group and 210 in the control group were recruited for

data analysis. At baseline, there were no significant

differences in the demographic and cardiovascular

risk factor profiles between the two groups, except

that patients in the intervention group had a higher

mean LDL level and a lower mean diastolic BP (Table 2).

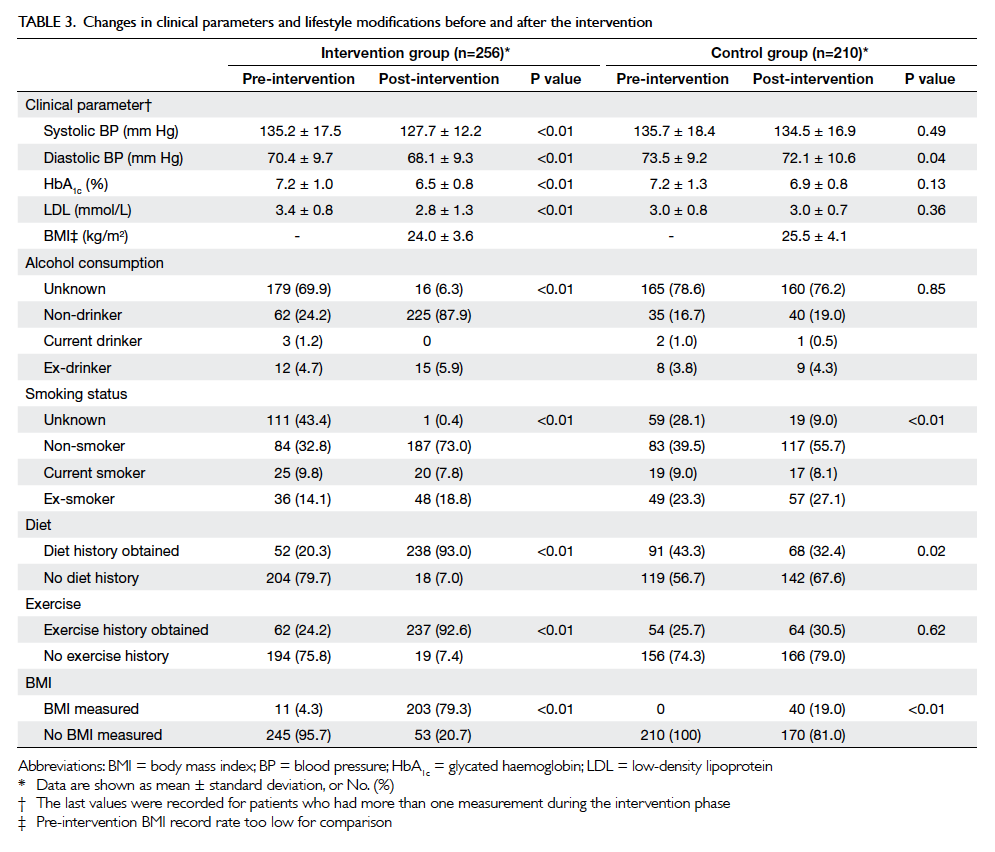

After the intervention period, significant

improvements in systolic BP, HbA1c and

LDL levels were observed in the intervention group

(Table 3). There were significant improvements in

all lifestyle modification parameters (alcohol and

smoking status, obtaining exercise and diet history, and BMI

measurement) in the intervention group (P<0.01),

and the control group had improvements in smoking

status (P<0.01) and BMI measurement (P<0.05)

[Table 3].

Table 3. Changes in clinical parameters and lifestyle modifications before and after the intervention

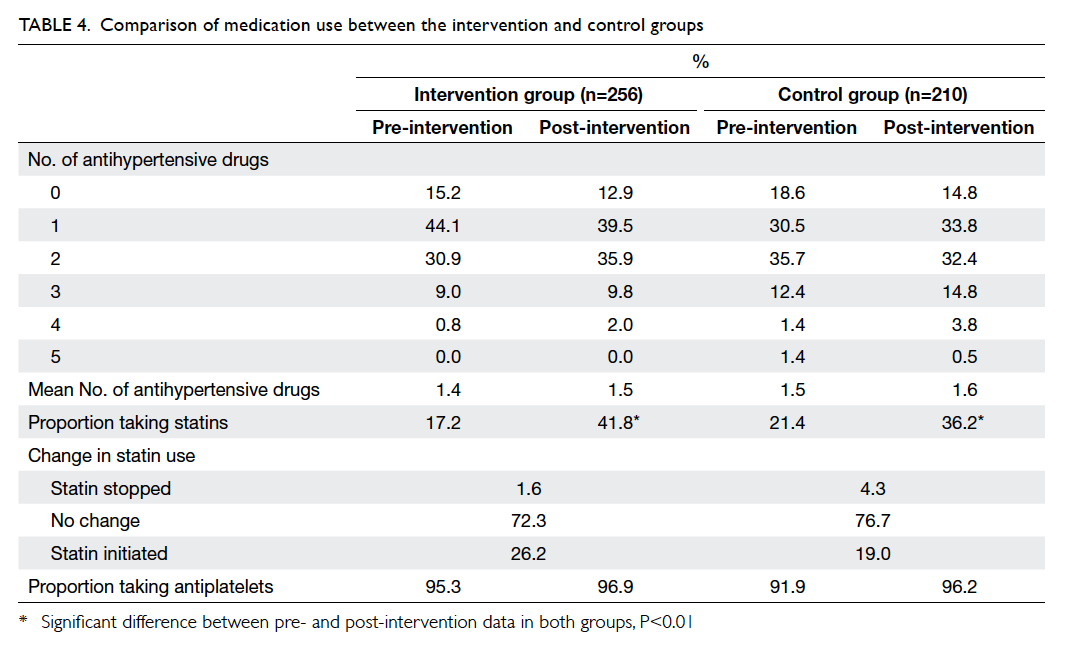

There was no significant increase in the number

of antihypertensive drugs prescribed in either group

(Table 4). Approximately 96% of patients were taking

an antiplatelet after the intervention period in both

clinics (Table 4) and the antiplatelet was always

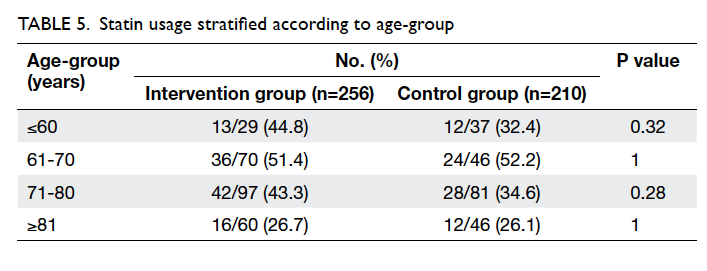

aspirin. The proportion of patients prescribed statins

increased significantly in both groups since the

introduction of simvastatin to the GOPC formulary

in 2009. However, the overall proportion of statin

use was still below 50%. Statins were less frequently

prescribed to patients older than 80 years (Table 5).

Statins were stopped for 1.6% of patients in the

intervention group and 4.3% in the control group

(Table 4). Statins were discontinued because of

dyspepsia for all patients in the intervention group.

The reasons for stopping statins for the control

group were dyspepsia, myalgia, mild liver function

derangement, hypotension, hypoglycaemia, and

drug-induced hepatitis. Only two patients in the

control group required emergency admission for

hypoglycaemia during the intervention period.

There was no restroke in the intervention group

and four restrokes in the control group during the

intervention period.

Discussion

This study showed that the implementation of

a secondary stroke prevention programme in

GOPCs could improve control of cardiovascular

risk factors, including BP, HbA1c and

LDL levels among ischaemic stroke patients. We observed

an improvement of BP control in the

intervention group, although there was no significant

increase in the number of antihypertensives used.

However, since simvastatin was introduced into the

GOPC drug formulary in 2009, the use of statins

increased in both the control and intervention

clinics, although the effect of LDL reduction was

only observed in the intervention group. This

result implies that the improvement in outcome

for this group is due to more than just the effects of

medications. Lifestyle modifications may provide

additional benefits.

Although the BP and HbA1c level

in the intervention group were comparable with

recent recommendations (BP <140/90 mm Hg for

patients without diabetes; BP <130/80 mm Hg and

HbA1c level of <7% for patients with diabetes), the mean

LDL levels remained well above the recommended

target of 1.9 mmol/L. Only about half of the

patients were taking statins. There is a suggestion

that doctors may not prescribe or maximise statin

therapy because treatment may be considered futile,

especially among older people whose life expectancy

is limited.15 This trend was observed in both the

control and intervention sites in this study (Table 4). The percentage of patients taking statins was

relatively low in this study as some doctors may have

concerns about the possible side-effects. However,

no severe adverse effects of statins were noted in

the intervention group despite the more aggressive

treatment approach.

The implementation of secondary stroke

prevention protocol has raised doctors’ awareness

of lifestyle modification for patients with ischaemic

stroke. This was reflected by the significant

increase in the use of lifestyle modifications in the

intervention group. We encouraged doctors to

provide appropriate advice on lifestyle modification

when lifestyle risk factors were identified during the

consultation. However, due to heavy patient loads in

the GOPC, no additional time can be allocated for

medical consultations. During clinic meetings, our

staff expressed difficulty in providing quality lifestyle

education due to limited consultation time. The lack

of additional resources for lifestyle education was a

main shortcoming of this programme.

Certain subgroups of ischaemic stroke patients

are not well represented by this study, for example,

those with atrial fibrillation. Atrial fibrillation is

one of the major risk factors for recurrent stroke.16

However, as warfarin was not available in the drug

formulary of the GOPCs during the study period,

most patients with atrial fibrillation were not

referred to these clinics. Only a few patients with

atrial fibrillation were identified in our study and

all of them had a contra-indication for warfarin. At

the time of writing, warfarin has become available

in the GOPCs and several novel anticoagulants have

been introduced as self-finance items. The use of

anticoagulants in GOPCs is an important aspect of

secondary stroke prevention that warrants further

investigation.

Implementation of evidence-based guidelines

into routine clinical practice is complicated.17 18

Physicians usually have concerns about the

applicability of new trial data to individual patients,

and it takes time for them to change their practice.

Apart from considering the best available evidence,

we also need to take into account the practical

barriers in the clinical practice setting. The heavy

workload in the clinic, shortage of consultation time,

and limited scope of the drug formulary may impose

difficulty in introducing an evidence-based protocol

to local GOPCs.

From the experience of this study, a dedicated

training session for clinic staff is necessary

before the implementation of any new protocol.

Additional review sessions are needed to audit

clinicians’ compliance with the protocol. Review of

the GOPC drug formulary, for example, to include

greater choices of statins and antiplatelets, may

be helpful to improve the care of stroke patients.

Lifestyle modification is an important aspect for

secondary stroke prevention, but time constraints

in busy GOPCs are always an issue. A designated

nurse clinic for patient education and annual risk

factor monitoring should be introduced. For better

utilisation of resources, it is beneficial to recruit

community partners from allied health services to

provide a structured secondary stroke prevention

programme for patient empowerment and

engagement.

In our study, approximately 5% to 6% of

patients were lost to other GOPCs and medical

clinics (Table 1). This may introduce some bias. In addition, differences between the two clinics such

as proportions of health care workers, doctors’

qualifications, and differences in the socio-economic

groups of the patients are possible confounders that

might introduce bias. The intervention group had a

higher rate of dropouts due to death and restroke

although this was not statistically significant. As

most of these patients had no change in medications

during the intervention period (Table 1), the higher death and restroke rates were unlikely to be related to

any adverse effects from the implementation of the

protocol. However, we do not have data on the rates

of stroke recurrence, adverse events, and mortality

over a longer period, which are the most important

outcomes for effective secondary stroke prevention.

Furthermore, we may need to take into account the

Hawthorne effect when looking at the effectiveness

of the protocol implementation, in that physicians

perform better simply because they are aware that

they are in a study rather than because of the nature

of the protocol.19 20 This is an unavoidable bias in

clinical research.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that through

implementation of a standardised treatment

protocol, the standard of care of secondary stroke

prevention for ischaemic stroke patients could

be improved in local GOPCs. However, due to

the relatively small sample size in this study, this

preliminary result should be interpreted with

caution and further studies involving more primary

care clinics are required to test its clinical value.

References

1. The top ten causes of death. (Fact sheet No 310/July 2013).

Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

2. Centre for Health Protection. Vital statistics: death rates

by leading causes of death, 2001-2012. Hong Kong:

HKSAR Government.

3. Centre for Health Protection. Health topics: non

communicable diseases and risk factors: cerebrovascular

disease. Available from: http://www.chp.gov.hk/en/content/9/25/58.html. Accessed 31 Mar 2014.

4. Cheung CM, Tsoi TH, Hon SF, et al. Outcomes after first-ever

stroke. Hong Kong Med J 2007;13:95-9.

5. Tsoi TH, Huang CY, Hon SF, et al. Trends in stroke types

and mortality in Chinese. Stroke 2004;35:e256.

6. Wong HC, Mok CT. Update on secondary stroke

prevention. Hong Kong Pract 2007;29:271-6.

7. Wang Y, Wu D, Wang Y, Ma R, Wang C, Zhao W. A survey

on adherence to secondary ischemic stroke prevention.

Neurol Res 2006;28:16-20. Crossref

8. Whitford DL, Hickey A, Horgan F, O’Sullivan B, McGee H,

O’Neill D. Is primary care a neglected piece of the jigsaw in

ensuring optimal stroke care? Results of a national study.

BMC Fam Pract 2009;10:27. Crossref

9. Ovbiagele B, Drogan O, Koroshetz WJ, Fayad P, Saver JL.

Outpatient practice patterns after stroke hospitalization

among neurologists. Stroke 2008;39:1850-4. Crossref

10. Rudd AG, Lowe D, Hoffman A, Irwin P, Pearson M.

Secondary prevention for stroke in the United Kingdom:

results from the National Sentinel Audit of Stroke. Age

Ageing 2004;33:280-6. Crossref

11. Xu G, Liu X, Wu W, Zhang R, Yin Q. Recurrence after

ischemic stroke in Chinese patients: impact of uncontrolled

modifiable risk factors. Cerebrovasc Dis 2007;23(2-3):117-20. Crossref

12. Sacco RL, Adams R, Albers G, et al. Guidelines for prevention of stroke in

patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack:

a statement for healthcare professionals from the American

Heart Association/American Stroke Association Council

on Stroke: co-sponsored by the Council on Cardiovascular

Radiology and Intervention: the American Academy

of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline. Stroke

2006;37:577-617. Crossref

13. Adams RJ, Albers G, Alberts MJ, et al. Update to the AHA/ASA

recommendations for the prevention of stroke in

patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack. Stroke

2008;39:1647-52. Crossref

14. Furie KL, Kasner SE, Adams RJ, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke

in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: a

guideline for healthcare professionals from the American

Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke

2011;42:227-76. Crossref

15. Walker DB, Jacobson TA. Initiating statins in the elderly:

the evolving challenge. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes

Obes 2008;15:182-7. Crossref

16. Li R, Cheng S, Mok M, et al. Atrial fibrillation is an

independent risk factor of poor stroke outcome and

mortality in Chinese ischaemic stroke patients. Cerebrovasc

Dis 2013;36(Supp 1):74.

17. Cranney M, Warren E, Barton S, Gardner K, Walley T.

Why do GPs not implement evidence-based guidelines? A

descriptive study. Fam Pract 2001;18:359-63. Crossref

18. Foy R, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Why does primary care need

more implementation research? Fam Pract 2001;18:353-5. Crossref

19. Wickström G, Bendix T. The “Hawthorne effect”—what

did the original Hawthorne studies actually show? Scand J

Work Environ Health 2000;26:363-7. Crossref

20. McCarney R, Warner J, Iliffe S, van Haselen R, Griffin M,

Fisher P. The Hawthorne effect: a randomised, controlled

trial. BMC Med Res Methodol 2007;7:30. Crossref