Hong Kong Med J 2015 Jun;21(3):243–50 | Epub 22 May 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144404

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Double balloon catheter for induction of labour in Chinese women with previous caesarean

section: one-year experience and literature review

Queenie KY Cheuk, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1;

TK Lo, MB, BS, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)2;

CP Lee, FRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)2;

Anita PC Yeung, FRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1

1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Queen Mary Hospital, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Queenie KY Cheuk (cheuky3@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Objectives: To evaluate the efficacy and safety of

double balloon catheter for induction of labour in

Chinese women with one previous caesarean section

and unfavourable cervix at term.

Design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: A regional hospital in Hong Kong.

Patients: Women with previous caesarean

delivery requiring induction of labour at term and with an unfavourable cervix from May 2013 to April

2014.

Major outcome measures: Primary outcome

was to assess rate of successful vaginal delivery

(spontaneous or instrument-assisted) using double

balloon catheter. Secondary outcomes were double

balloon catheter induction-to-delivery and removal-to-delivery interval; cervical score improvement;

oxytocin augmentation; maternal or fetal

complications during cervical ripening, intrapartum

and postpartum period; and risk factors associated

with unsuccessful induction.

Results: All 24 Chinese women tolerated double

balloon catheter well. After double balloon catheter

expulsion or removal, the cervix successfully ripened

in 18 (75%) cases. The improvement in Bishop

score 3 (interquartile range, 2-4) was statistically

significant (P<0.001). Overall, 18 (75%) cases were

delivered vaginally. The median insertion-to-delivery

and removal-to-delivery intervals were

19 (interquartile range, 13.4-23.0) hours and 6.9 (interquartile range, 4.1-10.8) hours, respectively.

Compared with cases without, the interval to delivery

was statistically significantly shorter in those with

spontaneous balloon expulsion or spontaneous

membrane rupture during ripening (7.8 vs 3.0

hours; P=0.025). There were no major maternal or

neonatal complications. The only factor significantly

associated with failed vaginal birth after caesarean

was previous caesarean section for failure to progress

(P<0.001).

Conclusions: This is the first study using double

balloon catheter for induction of labour in Asian

Chinese women with previous caesarean section.

Using double balloon catheter, we achieved a vaginal

birth after caesarean rate of 75% without major

complications.

New knowledge added by this

study

- This is the first report from Asian Chinese women on the use of double balloon catheter (DBC) for induction of labour in the presence of a caesarean scar. Using DBC, a vaginal birth after caesarean (VBAC) rate of 75% was achieved without major complications.

- During cervical ripening with DBC, cases with spontaneous balloon expulsion or spontaneous membrane rupture had a more favourable outcome with shorter interval to delivery.

- Previous caesarean section for failure to progress was significantly associated with failed VBAC.

- Our anecdotal experience with DBC was favourable and its application may reduce repeated caesarean section rates. Further research exploring this potential is warranted and large randomised controlled trials are needed to confirm its efficacy.

Introduction

There is widespread public and professional concern

about the increasing rates of caesarean section (CS).

In the UK and North America, around 25% and 32%

of births respectively were by CS.1 2 In Hong Kong,

according to the 2009 territory-wide O&G audit

report, CS rate has been around 42.1%.3 Previous CS

has been the most common indication for caesarean

delivery.3 In subsequent pregnancies, CS can be

associated with serious maternal morbidities.4 To

reduce CS rate and related morbidities, vaginal birth

after caesarean (VBAC) is an alternative advocated

in most developed countries.2 5 6 According to the

UK and North American guidelines, induction of

labour (IOL) can be offered to women with medical

or obstetric indications who opt for VBAC after

discussion.2 5

Unfavourable cervix, which is a common

obstetric problem, can be addressed using

pharmacological and mechanical methods to enable

cervical ripening. In Hong Kong pharmacological

method is more commonly used for IOL. In

women with previous CS, the increased risk of

uterine rupture is a major concern during IOL.2 5 6 7

Mechanical methods apply pressure on the internal

cervical os, stretch the lower uterine segment, and

increase local production of prostaglandin. There is

a lack of compelling evidence suggesting increased

risk of uterine rupture because mechanical devices

can be readily removed when needed and are stable

in room temperature. Compared to conventional

Foley catheter, the double balloon catheter (DBC)

has a cervicovaginal balloon in addition, allowing

greater compression of the cervical os and avoiding

the need for traction (Fig 1). Nevertheless, there are limited reports about the experience with the use of

DBC. Regarding the question of which IOL method is

suitable in women with prior CS, a recent Cochrane

review stated that there was insufficient information

available to conclude on the optimal method of IOL

in women with prior CS.7

Since May 2013, our unit has been offering

the option of DBC (Cook Cervical Ripening

Balloon; Cook Medical, Bloomington [IN], US) for

IOL in women with one previous CS. Therefore,

we conducted a study on Chinese women with an

objective to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the

DBC in IOL with one previous CS and unfavourable

cervix at term. Another objective was to identify

risk factors associated with unsuccessful VBAC. This

is one of the first studies to report using DBC for this

indication in Asian Chinese population.

Methods

This retrospective study was conducted in the

obstetrics unit of Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern

Hospital in Hong Kong. The unit provides tertiary

care and conducts over 3000 deliveries per year. Prior

to the introduction of DBC, the background CS and

VBAC rates in our unit was approximately 30% and

1.9%, respectively. The overall success rate of VBAC

was more than 80%. In our study, we identified VBAC

cases using DBC for IOL between 1 May 2013 and

30 April 2014 through the departmental database.

Clinical details were reviewed from the case notes

and hospital electronic systems.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were women with one lower

transverse caesarean scar and no contra-indication

for VBAC who were given the option of either

repeated elective CS or VBAC. Those VBAC cases

requiring medically or obstetrically indicated IOL

were offered DBC if the cervix was unfavourable

(modified Bishop score <6) and membranes intact.

The exclusion criteria for using DBC were:

women with two or more previous CS, classical

CS scar, inverted T or J or low vertical incision in

previous CS; previous uterine scar for gynaecological

conditions, eg myomectomy, hysterotomy;

congenital uterine abnormality; twin pregnancy,

non-cephalic presentations, intra-uterine death,

suspected fetal distress; uterine fibroids which

may obstruct labour, placenta praevia, antepartum

haemorrhage, leaking, clinical chorioamnionitis,

suspected macrosomia (ultrasound estimated fetal

weight ≥4000 g), polyhydramnios (amniotic fluid

index ≥25 cm or single deepest pocket ≥8 cm),

congenital fetal abnormalities; and maternal diseases

or maternal infection which would contra-indicate

vaginal delivery or warrant prompt delivery. Ethical

approval for this study was obtained from the local

institutional human research ethics committee.

Induction-of-labour protocol

Eligible patients were admitted into hospital in the

evening and an initial Bishop score was obtained.

Cardiotocogram for 60 minutes, and ultrasound scan

to assess estimated fetal weight, liquor volume, fetal

wellbeing by umbilical artery Doppler and placental

location were performed. After informed consent, the

DBC was inserted according to the manufacturer’s

instruction. If the DBC insertion failed, women

would be offered CS the next day morning. The

procedure of DBC insertion in all patients was done

by one investigator (KY Cheuk). The uterine and

vaginal balloons were inflated in phases to 40-50

mL and 60 mL, respectively using normal saline.

After insertion, vaginal examination was performed

to confirm correct placement. The catheter was

taped to the woman’s inner thigh without tension.

Following insertion of catheter, continuous fetal

heart monitoring (CFHM) was done for 60 minutes.

The catheter was kept for 12 hours if spontaneous

expulsion did not occur, or removed earlier if there

was spontaneous rupture of membranes, excessive

vaginal bleeding, fetal distress, scar tenderness,

or patient intolerance. Immediately following

balloon expulsion or removal, the Bishop score was

reassessed, followed by an attempt to have artificial rupture of membranes (ARM) regardless of Bishop

score. To reduce the potential inter-observer bias,

the same investigator (KY Cheuk) assessed the

Bishop score before DBC insertion and immediately

after DBC expulsion or removal. Oxytocin infusion

(Syntocinon; Sandoz Pharmaceuticals, East Hanover

[NJ], US) was commenced if after ARM the uterine

contractions remained suboptimal at a rate of

1 mU/min and the infusion rate was doubled every

30 minutes until the uterine contractions were

regular at 3 minutes’ interval. The maximum dose

was capped at 8 mU/min. Oxytocin was not started

without membrane rupture or if the DBC was still

in place; CFHM was started after ARM till delivery.

Labour was managed by the attending obstetrician

and midwives. Assessment of labour progress and

administration of analgesia was made according to

departmental protocols. Group B streptococcus

prophylaxis was given according to departmental

protocol. It was commenced after DBC insertion

until delivery for group B streptococcus carriers.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was successful vaginal

delivery (spontaneous or instrument-assisted). The

secondary outcomes were: induction-to-delivery

interval; device-removal-to-delivery interval;

cervical score improvement; oxytocin augmentation;

maternal or fetal complications during cervical

ripening, intrapartum and postpartum period, which

included failed device insertion, inability to void

during insertion, intolerance of device necessitating

early removal, uterine hyperstimulation, uterine

rupture, fetal distress, abruption, antepartum

haemorrhage, cord prolapse, malpresentation,

meconium-stained liquor, intrapartum and

postpartum infection, postpartum haemorrhage,

readmission in puerperium period, neonate delivery

with Apgar score of <7 in 5 minutes, cord blood pH

of <7.2, admission to neonatal intensive care unit,

neonatal sepsis, respiratory distress syndrome and

neonatal death, and risk factors associated with

unsuccessful induction.

Uterine hyperstimulation was defined as either

the occurrence of five or more contractions in 10

minutes for two consecutive 10-minute period, or

a contraction lasting for at least 2 minutes, with or

without changes in fetal heart rate pattern. Uterine

rupture was defined as disruption of the uterine

muscle extending to and involving the uterine serosa

or disruption of the uterine muscle with extension to

the bladder or broad ligament.5 Uterine dehiscence

was defined as disruption of the uterine muscle with

intact uterine serosa.5 Intrapartum infection was

defined by maternal fever of ≥38°C during labour.

Failed IOL was defined as failed ARM after catheter

removal or cervical dilatation of <3 cm after at least

8 hours of optimal uterine contractions.

Literature review

We also conducted a literature search on PubMed,

Ovid Medline, EMBASE, Cochrane library database

of systematic reviews and open library using the

keywords “double balloon catheter”, “Atad balloon”,

“double balloon device”, “Foley catheter”, “induction”,

“previous caesarean section”, and “previous scarred

uterus”. Bibliographies of all relevant articles

identified were searched manually to locate

additional studies. We excluded non-English

publications, or if the original paper was not available

from various sources such as PubMed, local hospital

or universities library systems and internet.

Statistical analyses

The statistical analysis was done by PASW Statistics

18, Release Version 18.0.0 (SPSS Inc, 2009, Chicago

[IL], US). Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical

data, while independent t test was used if normally

distributed, and non-parametric test (ie Mann-Whitney U test) if highly skewed. Univariate analysis

was used to assess the risk factors associated with

unsuccessful VBAC. To identify the differential

effect over time, Wilcoxon signed rank test was used

to compare the cervical Bishop scores before and

after DBC application. The critical level of statistical

significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

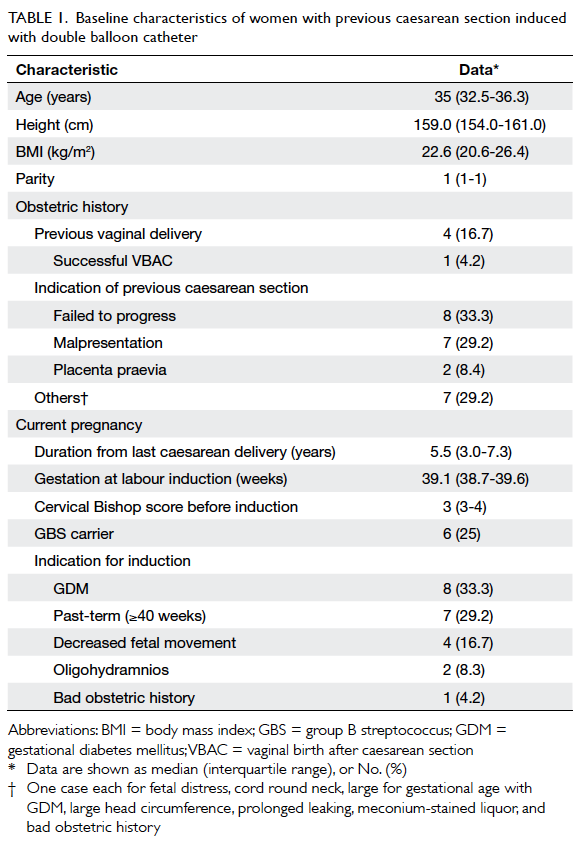

Twenty-five cases were identified during the 1-year

study period, and one non-Chinese woman’s data

were excluded. The remaining 24 cases were included

for analysis. Table 1 summarises the baseline

characteristics of study patients.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of women with previous caesarean section induced with double balloon catheter

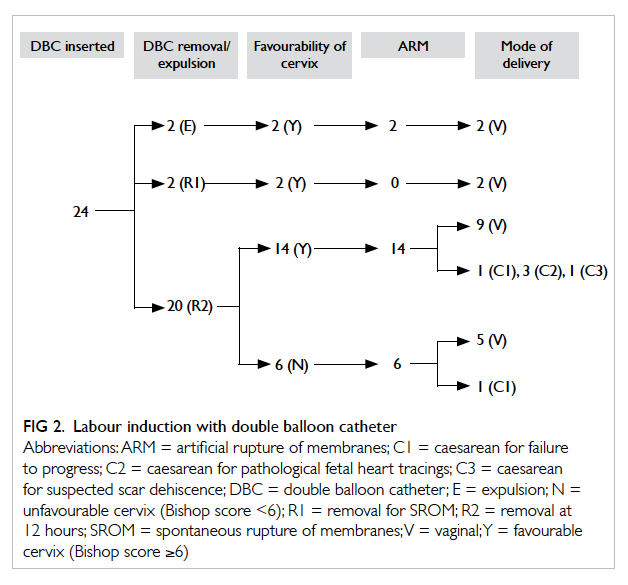

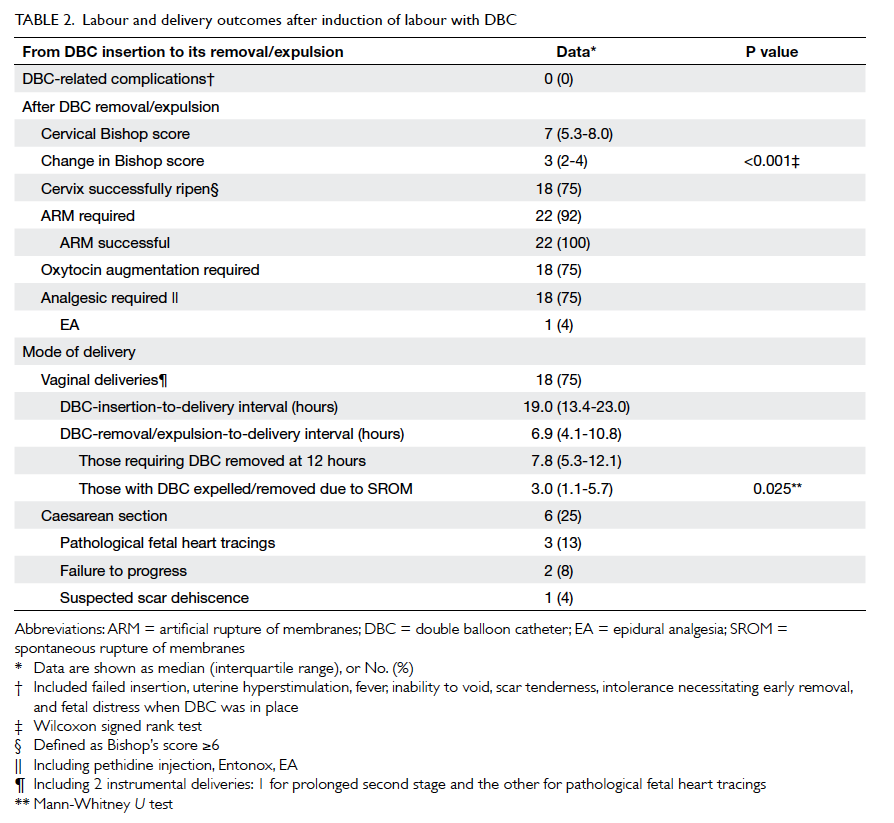

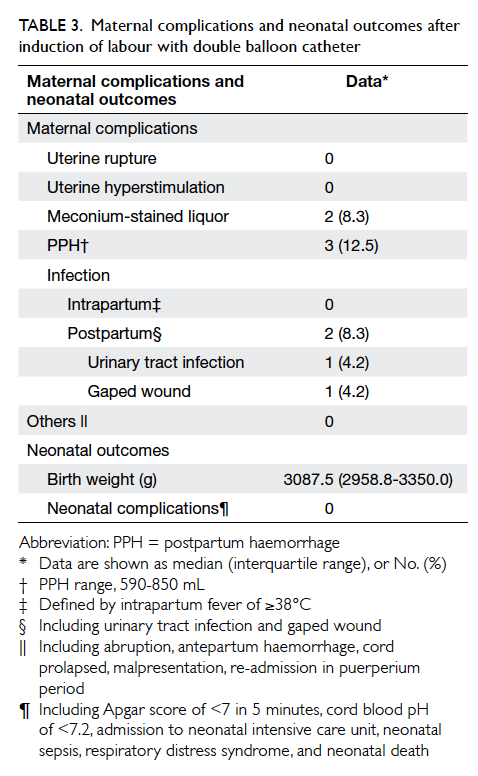

Figure 2 depicts the induction process and outcomes of the 24 cases; DBC was well tolerated

in all cases (Table 2). There was no case of failed insertion. After DBC expulsion or removal, the

cervix became favourable (Bishop’s score ≥6) in

18 (75%) cases. The improvement in Bishop score

3 (interquartile range [IQR], 2-4) was statistically

significant (P<0.001). Artificial rupture of the

membranes was successful in all 22 cases with intact

membranes, regardless of cervical favourability.

Oxytocin augmentation was required in 18 (75%)

cases. Overall, 75% of cases were delivered vaginally.

Among them, the median insertion-to-delivery

and removal-to-delivery intervals were 19 (IQR,

13.4-23.0) hours and 6.9 (IQR, 4.1-10.8) hours,

respectively. All the four women with previous

vaginal deliveries had successful VBAC. Compared

with cases without, the balloon expulsion-to-delivery

or removal-to-delivery interval was shorter in those

with spontaneous balloon expulsion or early balloon

removal due to spontaneous membrane rupture

during ripening (7.8 vs 3.0 hours, P=0.025). All the

cases had good neonatal outcomes with cord blood

pH of >7.25, 5-minute Apgar score of 10, without

the need for neonatal intensive care unit admissions

(Table 3). One case reported severe scar pain

during oxytocin augmentation. Scar dehiscence was

suspected and emergency CS performed. Dehiscence

was not substantiated intra-operatively. The baby

was born in good condition. Apart from a few cases

of maternal complications (eg postpartum infection

and postpartum haemorrhage), there was no case of

uterine rupture or adverse neonatal complications.

Table 3. Maternal complications and neonatal outcomes after induction of labour with double balloon catheter

To study the risk factors associated with

unsuccessful VBAC, univariate analysis was

performed using maternal age, height, body mass

index, cervical Bishop score, cervical favourability

after DBC removal or dislodgement, gender and

birth weight of baby, gestational diabetes mellitus,

history of vaginal delivery, history of successful

VBAC, inter-pregnancy interval, the indication

for previous CS, and the indication for IOL in the

current pregnancy as variables. Previous CS for

failure to progress was the only factor significantly

associated with unsuccessful VBAC (P<0.001).

Discussion

Few studies have investigated the use of DBC for

IOL in patients with previous caesarean scars.

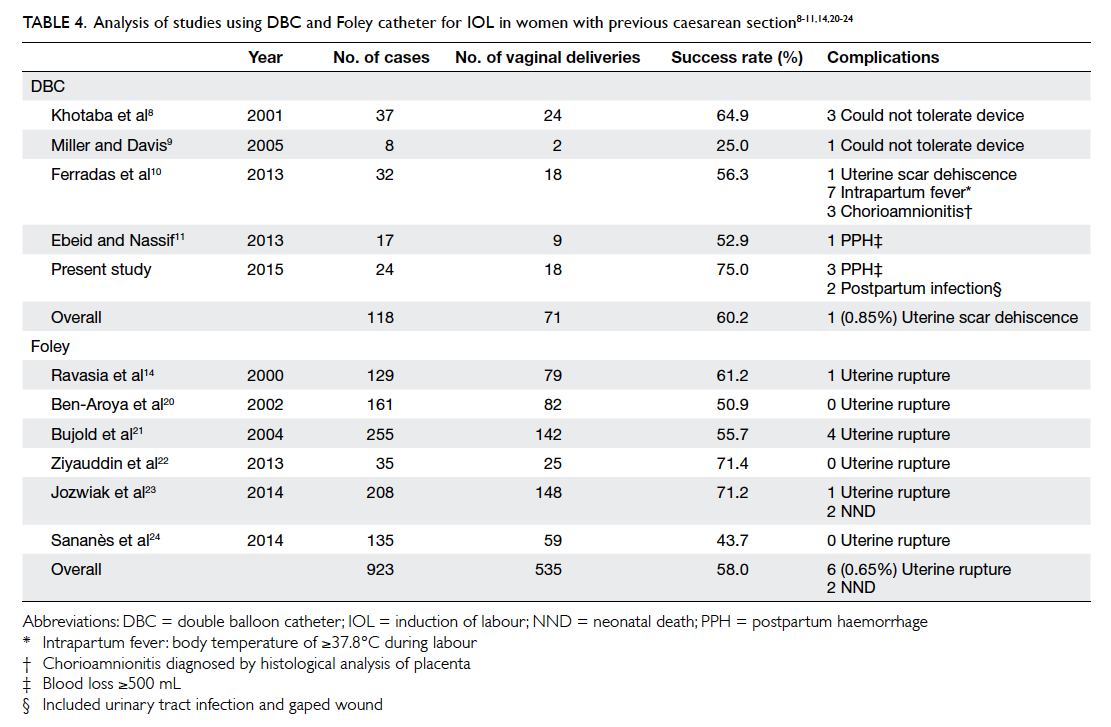

Table 4 summarises the findings from some of the studies8 9 10 11 including the current study. Most of the

studies showed significant improvement in Bishop

score after using the device and a favourable cervix

was achieved in 75% to 85% of cases. The overall

vaginal delivery rate was 60.2% (71/118). There was

one (0.85%) case of symptomatic scar dehiscence,

and no adverse neonatal complications. The cervical

ripening success rate in our study was comparable to

those in other studies, and also our study achieved

a higher vaginal delivery rate. One explanation for

this would have been due to differences in the IOL

protocols. Some authors would offer CS directly

if the cervix failed to ripen after the DBC.9 Our

practice was to continue induction with ARM and

oxytocin even if the cervix remained unfavourable

after the DBC. In our patients, 83.3% (5/6) in this

group delivered vaginally with continued induction.

A second potential reason for better outcomes in our

study would lie in the differences in inclusion criteria.

Some studies had excluded women with previous

vaginal delivery,10 a factor known to be associated

with successful VBAC. A third reason could have

been differences in ethnicity. Studies have shown

that ethnicity does impact VBAC success rates.12

Table 4. Analysis of studies using DBC and Foley catheter for IOL in women with previous caesarean section8 9 11 14 20 21 22 23 24

With increasing rates of CS worldwide, it is

estimated that 10% of women requiring IOL have

a history of CS. However, the optimal induction

method for this high-risk group is unknown. To

counter unfavourable cervix with intact membranes,

prostaglandins and mechanical methods such

as Foley or DBC have been used. Prostaglandins

appeared to be associated with a higher uterine

rupture risk.13 14 Ravasia et al14 found that the relative

risk of uterine rupture with prostaglandins versus

spontaneous labour was 6.41, whereas the risk

with the use of Foley catheter was comparable to

spontaneous labour. Although infective morbidity

associated with mechanical induction is a concern,

the evidence is contradictory.15 16 A systematic

review by Heinemann et al15 on studies using Foley

catheter for IOL showed that use of mechanical

devices was associated with significant increase

in maternal morbidity due to infectious morbidity

when compared with pharmacological agents. On

the other hand, a recent Cochrane review showed no

increase in serious maternal morbidity with the use

of the Foley catheter.7 Further support was provided

from the recent open-label randomised controlled

trial PROBAAT,16 which compared Foley catheter

to vaginal prostaglandin in 824 women without

previous CS. The study showed that Foley catheter

had similar CS rates, less uterine hyperstimulation,

fewer maternal and fetal morbidities, and no increase

in infectious morbidity. Although Foley catheter

was featured in all these studies, DBC potentially

has additional utility for an unripe cervix as it

applies pressure on both the external and internal

os, avoiding the need for traction and reduces the

associated patient discomfort. Double balloon

catheter has a larger inflated volume compared

with Foley catheter (80 mL vs 30 mL) and therefore

IOL with a bigger balloon volume may shorten

duration of labour with better cervical dilatation.17

Nevertheless, clinical data comparing DBC with

Foley catheter in the presence of a caesarean scar are

lacking, while those on intact uterus are scarce and

inconclusive.18 19

Table 4 summarises the results of studies using Foley catheter for IOL in the presence of a caesarean

scar.14 20 21 22 23 24 It appears that DBC achieved comparable

vaginal delivery rate (60.2% vs 58.0%) and similar

uterine rupture/dehiscence rate (0.85 % vs 0.65%).

There was no case report of neonatal death in studies

using DBC while there were two cases reported with

Foley catheter. One was due to uterine rupture;

another was due to rupture of vasa praevia which was

independent of the method of induction.23 Further

research to compare the efficiency and safety of the

two devices for IOL in women with previous CS is

warranted. Although uterine rupture and infectious

morbidity seemed rare with DBC in women with

previous CS, the number of women studied was too

small to allow solid conclusion on its safety.

The complication rate for VBAC attempt was

highest in those who failed to achieve VBAC in the

end.25 Knowledge of the factors associated with

successful VBAC would therefore enable better

counselling on the choice of mode of delivery. Landon

et al12 in a large cohort of 14 529 women showed that

previous vaginal delivery and previous successful

VBAC were the best predictors of successful VBAC;

the success rates were 86.6% and 89.6%, respectively.

In our study, all four cases with previous vaginal

delivery (including one with previous VBAC) had

successful VBAC. In the study by Landon et al,12

factors associated with unsuccessful VBAC included

obesity, previous CS for dystocia, IOL, birth weight of

<4000 g, advanced maternal age, short stature, more

than 2 years from previous caesarean, gestational age

of ≥41 weeks, and previous preterm CS. Despite our

small sample size, we concurred that previous CS for

failure to progress was a significant factor associated

with unsuccessful VBAC.

Conclusions

This is the first report from East Asia on the use

of DBC for IOL in the presence of caesarean scar.

A success rate of 75% was achieved using VBAC

in Chinese women with a caesarean scar and an

unfavourable cervix. The procedure of DBC was

well tolerated, and no major complications were

observed. Our favourable experience with DBC

in Asian Chinese women lends support to further

research exploring the potential of this promising

modality in averting the rising CS rates in this part

of the world.

References

1. Caesarean section. NICE Clinical Guidelines. National

Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health

(UK). London: RCOG Press; November 2011.

2. Vaginal birth after previous Caesarean delivery.

ACOG Practice Bulletin. No. 115. American College of

Obstetricians and Gynecologists; August 2010.

3. HKCOG Territory-wide O&G Audit Report: Caesarean

section. Hong Kong: Hong Kong College of Obstetricians

and Gynaecologists; 2009.

4. Bates GW Jr, Shomento S. Adhesion prevention in patients

with multiple cesarean deliveries. Am J Obstet Gynecol

2011;205(6 Suppl):S19-24. Crossref

5. Birth after previous Caesarean birth. RCOG Green-top

Guideline No. 45. Royal College of Obstetricians and

Gynaecologists; February 2007.

6. Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada.

SOGC clinical practice guidelines. Guidelines for vaginal

birth after previous caesarean birth. Number 155 (Replaces

guideline Number 147), February 2005. Int J Gynaecol

Obstet 2005;89:319-31.

7. Jozwiak M, Dodd JM. Methods of term labour induction

for women with a previous caesarean section. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev 2013;(3):CD009792. Crossref

8. Khotaba S, Volfson M, Tarazova L, et al. Induction of labor

in women with previous cesarean section using the double

balloon device. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2001;80:1041-2. Crossref

9. Miller TD, Davis G. Use of the Atad catheter for the

induction of labour in women who have had a previous

Caesarean section—a case series. Aust N Z J Obstet

Gynaecol 2005;45:325-7. Crossref

10. Ferradas E, Alvarado I, Gabilondo M, Diez-Itza I, García-Adanez J. Double balloon device compared to oxytocin for

induction of labour after previous caesarean section. Open

J Obstet Gynecol 2013;3:212-6. Crossref

11. Ebeid E, Nassif N. Induction of labor using double balloon

cervical device in women with previous cesarean section:

experience and review. Open J Obstet Gynecol 2013;3:301-5. Crossref

12. Landon MB, Leindecker S, Spong CY, et al. The MFMU

Cesarean Registry: factors affecting the success of trial

of labor after previous cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 2005;193:1016-23. Crossref

13. Lydon-Rochelle M, Holt VL, Easterling TR, Martin DP.

Risk of uterine rupture during labor among women with a

prior cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med 2001;345:3-8. Crossref

14. Ravasia DJ, Wood SL, Pollard JK. Uterine rupture during

induced trial of labor among women with previous

cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;183:1176-9. Crossref

15. Heinemann J, Gillen G, Sanchez-Ramos L, Kaunitz AM.

Do mechanical methods of cervical ripening increase

infectious morbidity? A systematic review. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 2008;199:177-87. Crossref

16. Jozwiak M, Oude Rengerink K, Benthem M, et al. Foley

catheter versus vaginal prostaglandin E2 gel for induction

of labour at term (PROBAAT trial): an open-label,

randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2011;378:2095-103. Crossref

17. Levy R, Kanengiser B, Furman B, Ben Arie A, Brown D,

Hagay ZJ. A randomized trial comparing a 30-mL and an

80-mL Foley catheter balloon for preinduction cervical

ripening. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;191:1632-6. Crossref

18. Salim R, Zafran N, Nachum Z, Garmi G, Kraiem N, Shalev

E. Single-balloon compared with double-balloon catheters

for induction of labor: a randomized controlled trial.

Obstet Gynecol 2011;118:79-86. Crossref

19. Mei-Dan E, Walfisch A, Valencia C, Hallak M. Making

cervical ripening EASI: a prospective controlled

comparison of single versus double balloon catheters. J

Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2014;27:1765-70. Crossref

20. Ben-Aroya Z, Hallak M, Segal D, Friger M, Katz M, Mazor

M. Ripening of the uterine cervix in a post-cesarean

parturient: prostaglandin E2 versus Foley catheter. J

Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2002;12:42-5. Crossref

21. Bujold E, Blackwell SC, Gauthier RJ. Cervical ripening with

transcervical foley catheter and the risk of uterine rupture.

Obstet Gynecol 2004;103:18-23. Crossref

22. Ziyauddin F, Hakim S, Beriwal S. The transcervical foley

catheter versus the vaginal prostaglandin e2 gel in the

induction of labour in a previous one caesarean section—a

clinical study. J Clin Diagn Res 2013;7:140-3. Crossref

23. Jozwiak M, van de Lest HA, Burger NB, Dijksterhuis MG,

De Leeuw JW. Cervical ripening with Foley catheter for

induction of labor after cesarean section: a cohort study.

Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2014;93:296-301. Crossref

24. Sananès N, Rodriguez M, Stora C, et al. Efficacy and safety

of labour induction in patients with a single previous

Caesarean section: a proposal for a clinical protocol. Arch

Gynecol Obstet 2014;290:669-76. Crossref

25. Landon MB, Hauth JC, Leveno KJ, et al. Maternal and

perinatal outcomes associated with a trial of labor after

prior cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2581-9. Crossref