Hong Kong Med J 2015 Feb;21(1):23–9 | Epub 30 Jan 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144266

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Predictive factors for colonoscopy complications

Annie OO Chan, MB, BS, MD1; Louis NW Lee, MB, BS, FRCS (Edin)2; Angus CW Chan, MB, ChB, MD2; WN Ho, BHSs (Nursing)2; Queenie WL Chan, BHSs (Nursing)3; Silvia Lau, MPH, MSc4; Joseph WT Chan, MB, BS, FRCOG5

1 Gastroenterology & Hepatology Centre, Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Happy Valley, Hong Kong

2 Endoscopy Centre, Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Happy Valley, Hong Kong

3 Nursing Administration Department, Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Happy Valley, Hong Kong

4 Medical Physics & Research Department, Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Happy Valley, Hong Kong

5 Hospital Administration Department, Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Happy Valley, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Queenie WL Chan (wlchan@hksh.com)

Abstract

Objective: To determine factors predicting

complications caused by colonoscopy.

Design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: A private hospital in Hong Kong.

Patients: All patients undergoing colonoscopy in

the Endoscopy Centre of the Hong Kong Sanatorium

& Hospital from 1 June 2011 to 31 May 2012 were

included. Immediate complications were those that

were recorded by nurses during and up to the day

after the examination, while delayed complications

were gathered 30 days after the procedure by

way of consented telephone interview by trained

student nurses. Data were presented as frequency

and percentage for categorical variables. Logistic

regression was used to fit models for immediate and

systemic complications with related factors.

Results: A total of 6196 patients (mean age, 53.7

years; standard deviation, 12.7 years; 3143 women)

were enrolled and 3657 telephone interviews

were completed. The incidence of immediate

complications was 15.3 per 1000 procedures

(95% confidence interval, 12.3-18.4); 50.5% were

colonoscopy-related, including one perforation

and other minor presentations. Being female (odds

ratioadjusted=1.6), use of monitored anaesthetic care

(odds ratioadjusted=1.8), inadequate bowel preparation

(odds ratioadjusted=3.5), and incomplete colonoscopy

(odds ratioadjusted=4.5) were predictors of risk for all

immediate complications (all predictors had P<0.05

by logistic regression). The incidence of delayed

complications was 1.6 per 1000 procedures (95%

confidence interval, 0.3-3.0), which comprised

five post-polypectomy bleeds and one post-polypectomy

inflammation. The overall incidence

of complications was 17.8 per 1000 procedures (95%

confidence interval, 13.5-22.1). The incidences of

complications were among the lower ranges across

studies worldwide.

Conclusion: Inadequate bowel preparation and

incomplete colonoscopy were identified as factors

that increased the risk for colonoscopy-related

complications. Colonoscopy-related complications

occurred as often as systemic complications,

showing the importance of monitoring.

New knowledge added by this

study

- The risks of local and systemic complications of colonoscopy are of paramount importance.

- Enforcing bowel preparation and post-polypectomy care may reduce the risk of delayed complications.

Introduction

Colonoscopy is an efficient, invasive, and

commonly used diagnostic tool with promising

therapeutic capacity. Common colonoscopy-related

complications include prolonged pain

and distension, and rarely draw medical attention

or lead to hospitalisation. Severe complications,

including bleeding and perforation, are potentially

life-threatening and require urgent management.

Although death is uncommon, occurring in no

more than 3 per 10 000 procedures, the incidence

of post-polypectomy bleeding and perforation

ranges from 1.6 to 14.8 and 0.2 to 1.0 per 1000

procedures, respectively.1 2 3 4 5 6 It is difficult to

accurately benchmark direct colonoscopy-related

complications due to the different outcome

measure definitions used in studies. For example,

some studies include immediate complications only,

while others extend the complication period to 7 or

30 days, and some studies include an extensive list

of complications while others include only bleeding

and perforation.1 2 5 7 8 9 10 Furthermore, the efficacy and

safety of the procedure vary across clinical settings

and the targeted populations. With no available local

data, consensus for complication incidence remains

inconclusive.

Intravenous sedation is routinely used during

colonoscopy to minimise the discomfort and pain

associated with the procedure. Endoscopists are

equipped to give sedatives and to monitor their

side-effects, but anaesthetists are often invited

to provide monitored anaesthetic care (MAC)

when the patient is considered to be at high risk

for complications, for instance, older patients and

those with multiple co-morbidities are particularly

vulnerable to complications. Systemic complications

vary from prolonged drowsiness to fatal events

such as cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events.

Cardiovascular events following sedation, such

as hypotension and myocardial infarction, during

colonoscopy have been reported to range from

0.1 to 59.1 per 1000 procedures. Cerebrovascular

events such as stroke range from 0.1 to 1.3 per 1000

procedures.3 6 10 The outcome variables are highly

heterogeneous, for example, Nelson et al’s study3

included myocardial infarction, vasovagal event, and

arrhythmia in the cardiovascular incidents, while

Ma et al’s study10 recorded hypotension only.10 Some

endoscopists opted to study complications related

to the use of carbon dioxide (CO2) insufflation and

absence of sedative use.11 12 13 This study aimed to record all complications systematically and to

determine the relevant risk factors.

Methods

This prospective study collected data for all

colonoscopies done from 1 June 2011 to 31

May 2012 at the Endoscopy Centre of the Hong

Kong Sanatorium & Hospital (HKSH), which is a private hospital in Hong Kong. Prior to

colonoscopy, patients were invited to give their

written consent for their participation in the study,

including for the 30-day follow-up telephone

interview. The Hospital Management Committee

involving the Research Ethics Committee of the

HKSH approved the study.

The complications were recorded by nurses

on a standard form during and immediately after

the procedure. The standard audit forms for

immediate and delayed colonoscopy complications

were designed by a research doctor, with the most

common complications based on literature review.

The immediate complications audit form

included patients’ demographics, use of sedation/analgesic/antispasmodic, use of MAC, gross

indications for colonoscopy (therapeutic or

diagnostic), type of therapeutic procedures

performed such as polypectomy, the reason for

incomplete colonoscopy (caecum intubation

failure), quality of bowel preparation (adequate –

good/adequate or not – fair/poor, which was rated

by the endoscopist), and the use of CO2 insufflation.

Complication data were divided into systemic and

colonoscopy-related complications. For systemic

complications, we captured data for nausea/vomiting, hypotension (systolic blood pressure

<100 mm Hg), bradycardia/tachycardia (heart rate

<50 to >100 beats/min), vasovagal fainting, and

other cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events.

For colonoscopy-related complications, data for

perforation, persistent pain/discomfort, abdominal

distension, and haemorrhage were gathered.

Delayed complications were defined as the

above events happening from the day after the

initial colonoscopy to the 30th day that required

readmission or admission to other hospitals. For

those readmissions, we automatically inspected

the records for the reasons and interventions if the

readmissions were complication-related. Otherwise,

trained student nurses or a research doctor

telephoned all consented participants to interview

for the 30-day complications using the delayed

complication audit form. A participant was declared

lost to follow-up after three telephone attempts. The

student nurses were trained by senior nurses and the

research doctor with standard instructions.

Data analysis was performed by the Statistical

Package for the Social Sciences (Windows version

14.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US). Descriptive

statistics (mean, percentage, incidence, and/or 95% confidence interval [CI]) were used to

display the characteristics of the sample. For those

complications with zero events, only 95% CIs were

given.14 Backward logistic regression analyses were

performed to draw prediction models for immediate

complications, including colonoscopy-related

complications or systemic complications, and overall

complications, including immediate and delayed

complications, from the sample; entering variables

were chosen from age, sex (male or female), use of

MAC (yes or no), sufficiency of bowel preparation

(adequate or not), and completion of colonoscopy

(yes or no) according to the results of the univariate

analyses by Pearson Chi squared tests of all potential

independent variables, with a significance level set

at 10%; variable inclusion in the iteration was set

at P<0.1 for backward logistic regression analyses.

Returning coefficients of the variables were

interpreted as adjusted odds ratio (ORadjusted) with

95% CI provided. All significance levels were set at

two-sided α=0.05.

Results

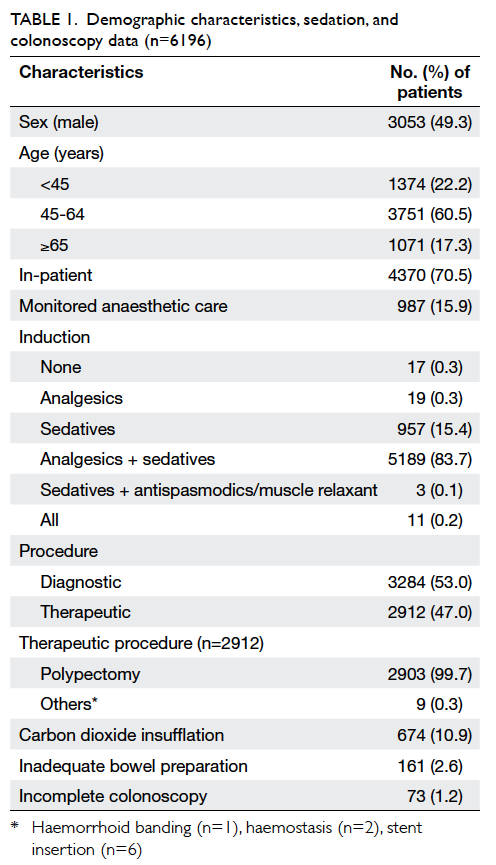

A total of 6196 colonoscopies (3143 women; mean

age 53.7 years; standard deviation, 12.7 years) were

done during the study period. Most patients were

aged between 45 and 64 years, were in-patients, had

undergone diagnostic colonoscopy, and received

intravenous sedation (60.5%, 70.5%, 53.0%, and

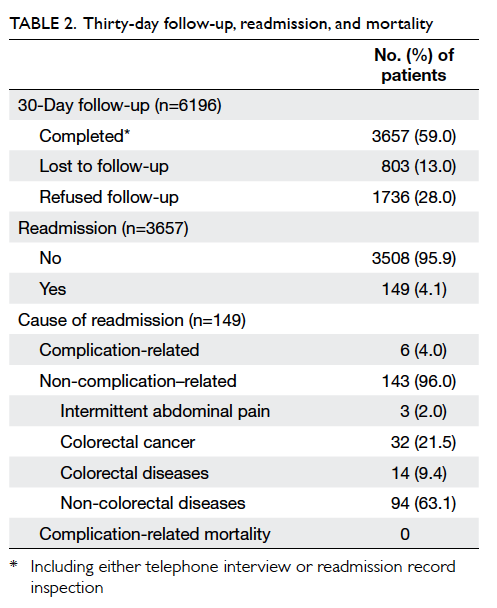

99.4% respectively; Table 1). The data for immediate

complications were complete, while the 30-day

follow-up was completed for 3657 procedures (803

were lost to follow-up and 1736 refused; compliance

rate 59.0%; Table 2).

Of the 6196 colonoscopies, 2912 were

therapeutic with 99.7% dedicated to polypectomy

(Table 1). There were 73 (1.2%) cases of incomplete

colonoscopy, 18 (24.7%) of which were due

to inadequate preparation. Other reasons for

incomplete colonoscopy were tumour obstruction

(15 of 73; 20.5%) and intention of sigmoidoscopy

or stent insertion (26 of 73; 35.6%). A total of 149

patients were readmitted within 30 days after

the procedure, of which six (4.0%) were related

to complications. The other reasons were cancer,

gastro-intestinal disease, or cardiac events (Table 2).

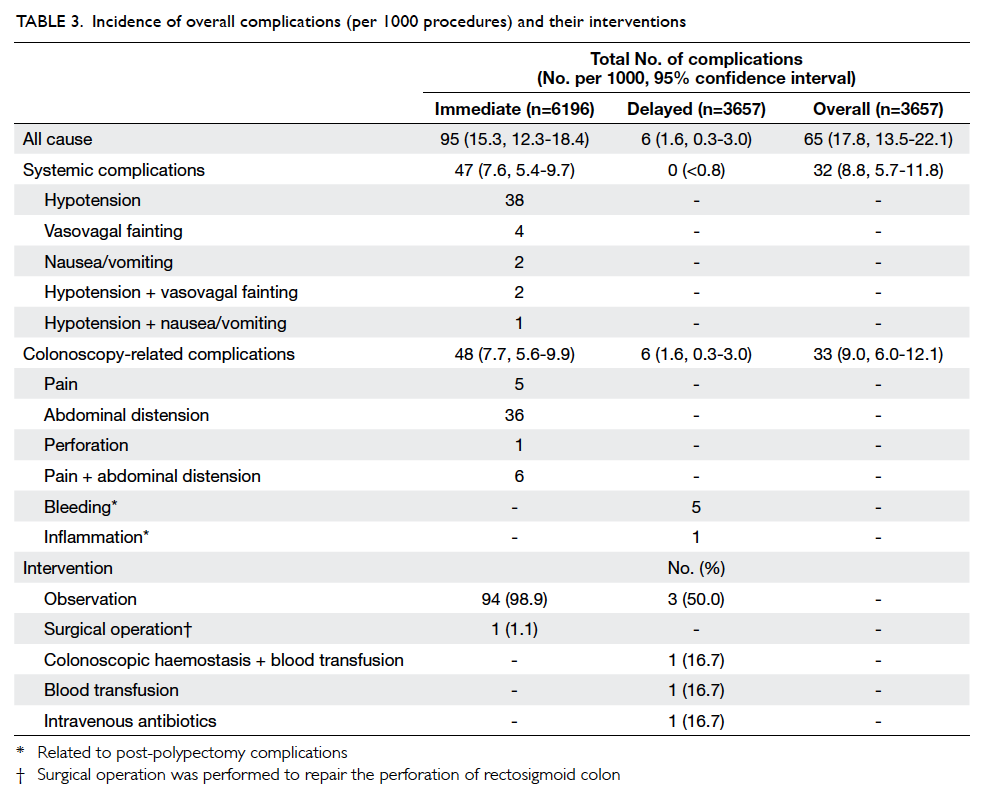

Systemic complications

Regarding the choice of sedation, midazolam and

pethidine were the most used at 81.5% and 82.0%,

respectively, while 15.9% of patients underwent

MAC. Immediate complications reported included

hypotension, vasovagal fainting, and nausea/vomiting, or a combination (6.1, 0.6, 0.3, and 0.5

per 1000 procedures, respectively; Table 3). There

were no severe cardiovascular events such as

heartbeat irregularity or myocardial infarction or

cerebrovascular events such as stroke. Furthermore,

none of the patients reported delayed systemic

complications in the 30-day follow-up.

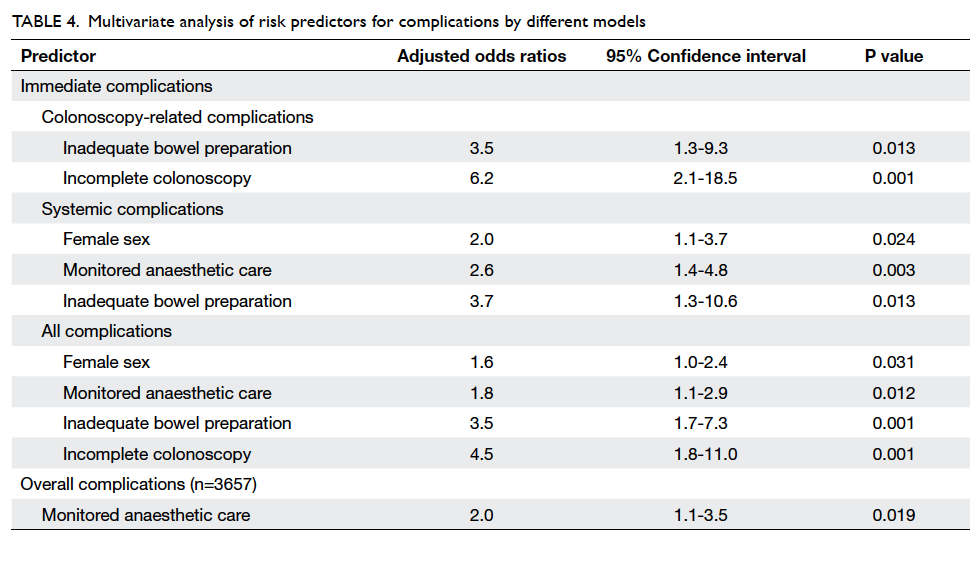

Modelling to study the potential risk factors

showed that being female, use of MAC, and

inadequate bowel preparation were the significant

independent predictors for systemic immediate

complications (ORadjusted=2.0, 2.6, and 3.7,

respectively; all were P<0.05; Table 4).

Colonoscopy-related complications

Immediate colonoscopy-related complications were

recorded for 48 patients (7.7 per 1000 procedures),

including extensive pain/discomfort, abdominal

distension, and perforation (Table 3). The only

perforation was at the sigmoid-rectal junction and

was due to adhesion, which might be related to

previous abdominal surgery (total hysterectomy and

bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was done 10 years

previously). In the 30-day follow-up, six patients

reported complication-related readmissions, five

of whom were for bleeding after discharge from

hospital and one was for inflammation; all were

caused by polypectomy.

Modelling was done to formulate a predictive

algorithm for significant independent risk factors

and outcome events (Table 4). Inadequate bowel

preparation and incomplete colonoscopy were the

significant predictors for immediate colonoscopy-related

complications (ORadjusted=3.5 and 6.2,

respectively; both were P<0.05) and for all immediate

complications (ORadjusted=3.5 and 4.5, respectively;

both were P<0.05). In the model for all immediate

complications, being female and use of MAC were

also predictors (ORadjusted=1.6 and 1.8, respectively;

all were P<0.05).

A predictive model was also done for overall

complications, including all immediate and delayed

complications among those who completed follow-up

at 30 days. The effect of previous significant

predictors was transient in that they did not predict

the overall complications occurring in the 30-day

post-colonoscopy period. Monitored anaesthetic

care was the only predictor during the 30-day period

(ORadjusted=2.0; P=0.019).

Discussion

Significance of this study

Inadequate bowel preparation and incomplete

colonoscopy were identified as risk factors

for colonoscopy-related complications. Other

complications were mostly hypotension and

abdominal distension. No myocardial infarction,

transient ischaemic attack, or death relating to

colonoscopy was reported.

Contribution of individual characteristics to

the complications

Colonoscopy is rarely a complication-free

procedure, but a good understanding of the possible

complications can help to minimise them. While

experienced endoscopists, diagnostic procedures,

and young patients are protective factors for

colonoscopy complications, trainee endoscopists,

therapeutic procedures, advanced age, female

sex, obesity, co-morbidity, anticoagulant use, and

previous abdominal surgery are risk factors for

complications.3 5 6 10 15 16 17 The relatively low incidence

of complications recorded in this study could be

attributed to the fact that more than half of the

procedures were diagnostic, thus reducing the

potential for polypectomy-associated complications.

Other events—such as abdominal pain and

distension, hypotension, vasovagal fainting, and

nausea/vomiting—accounted for 98.9% of all

immediate complications; these events were mostly

reported by women (60.6%; ORadjusted=1.6; Table

4). This result is consistent with the literature.17

This effect could possibly be explained by different

perceptions of somato-sensation, which could be

traced back to the socio-emotional cultivation and

cultural expectation of the different sexes.18

Hidden factors that may contribute to

complications

Despite the sex effect, use of MAC, inadequate

bowel preparation, and incomplete colonoscopy

were all related to immediate complications. The use

of MAC, in particular, requires more interpretation

because it has not been found to be a risk factor

in other studies and its use ought not be a cause

of complications. However, MAC is designed for

patients who are vulnerable to the complications of

sedation and the procedure, especially those with co-morbidities

and who are at an advanced age. In this

study, co-morbidity was not reviewed, but patients

who underwent MAC were significantly older than

those who did not (mean age, 56.1 vs 53.3 years;

P<0.001, t test) which may be partly contributory.

However, age was not significantly associated

with any of the complications after adjustment for

other factors. Age might have a greater impact if co-morbidity

was also considered and this may be an

area for further study.

Inadequate bowel preparation, in which faeces

obscure the inner lining of the colon, impedes the

vision and heightens the risk for complications.

Likewise, incomplete colonoscopy due to inadequate

bowel preparation or unbearable discomfort

inevitably increases the risk for complications. These

results are consistent with other studies.2 3 10

A large proportion (59%) of the study

population completed the study. Per protocol

univariate analyses showed that use of MAC was the

sole significant factor related to overall complications

(Table 4).

Other factors

Sedation-free colonoscopy is a feasible alternative

that could reduce the risk of systemic complications;

use of CO2 insufflation might increase its tolerability

while maintaining visibility. In this study, a sedation-free

procedure was performed in only 36 patients,

with no complications; CO2 insufflation was done for

647 (10.9%) patients instead of gas (room air), with

only minor complications encountered (two patients

reported abdominal distension and seven reported

hypotension/vasovagal fainting). Insufflation with

CO2 could be adopted more widely because it is

non-explosive, absorbable, and does not affect the

mucosal blood flow, thus minimising discomfort

and the risk of colonic ischaemia. According to

Bretthauer et al,19 CO2 insufflation leads to quicker

recovery, and less pain and complications. These

advantages are supported by other studies including

local research.11 19 20 These factors might inspire

greater use of CO2 insufflation and minimise use of

sedation for selected patients.12 13 21

Inadequate bowel preparation not only

hampers completion of the procedure, but also

increases the risk for complications. As evidenced

from the prediction models, inadequate bowel

preparation significantly increases the occurrence

of complications. In addition to implementing the

current standardised bowel preparation protocol,

enforcement of patient education, compliance, and

early admission for monitored bowel preparation

might help to further suppress the rate for inadequate

bowel preparation.

Limitations

Many of the patients were lost to contact by

telephone. In this study, we assumed that the pattern

of missing patients was random and was not affected

by whether or not the patients had complications.

However, self-selection bias might exist. If patients

without complications were more likely to be lost

to contact, the rate of delayed complications would

be overestimated. However, the rate of delayed

complications would be underestimated if the

patients had been admitted to other hospitals or had

died.

Endoscopist experience, and patient characteristics of co-morbidities and

severe symptoms before the procedure were not recorded for analysis

in this study. These are potential risk factors for

complications.

In view of the importance of monitoring the

complications of colonoscopy, further study might

include the missing variables of co-morbidity,

endoscopist experience, symptoms at presentation and oxygen level, and explore factors such as the

influence of body mass index and medical history,

sedation dose, indication for colonoscopy, use of

laxatives and compliance, and post-colonoscopy

diagnosis/pathology that might help to minimise the

variance on prediction of complications.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Sheri Lim, former

Administrative Officer (Medical) who proposed

and developed the audit. We are grateful to Dr KM

Lai, Head of Department of Anaesthesiology for his

expert advice on the anaesthetic terminology; Dr

Raymond Yung and Dr KN Lai, Assistant Medical

Superintendents for their valuable suggestions

and encouragement; Ms Grace Wong, Medical

Records Manager for coordinating with different

departments; and Ms Sara Fung, former Research

Nurse for coordinating the project. Also, thanks to all

doctors who contributed their knowledge and data,

for this study would not have been accomplished

without them.

References

1. Lorenzo-Zúñiga V, Moreno de Vega V, Doménech E,

Mañosa M, Planas R, Boix J. Endoscopist experience as a

risk factor for colonoscopic complications. Colorectal Dis

2010;12(10 Online):e273-7.

2. Gastrointestinal endoscopy, version 1. Australasian Clinical Indicator Report 2003-2010. Australian Council on Healthcare Standards; 2010.

3. Nelson DB, McQuaid KR, Bond JH, Lieberman DA, Weiss

DG, Johnston TK. Procedural success and complications

of large-scale screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc

2002;55:307-14. CrossRef

4. Rathgaber SW, Wick TM. Colonoscopy completion and

complication rates in a community gastroenterology

practice. Gastrointest Endosc 2006;64:556-62. CrossRef

5. Rabeneck L, Paszat LF, Hilsden RJ, et al. Bleeding and perforation after outpatient

colonoscopy and their risk factors in usual clinical practice.

Gastroenterology 2008;135:1899-1906, 1906.e1.

6. Viiala CH, Zimmerman M, Cullen DJ, Hoffman NE.

Complication rates of colonoscopy in an Australian

teaching hospital environment. Intern Med J 2003;33:355-9. CrossRef

7. Ko CW, Riffle S, Michaels L, et al. Serious complications within 30 days of screening

and surveillance colonoscopy are uncommon. Clin

Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;8:166-73. CrossRef

8. Singh H, Penfold RB, DeCoster C, et al. Colonoscopy and its complications across

a Canadian regional health authority. Gastrointest Endosc

2009;69:665-71. CrossRef

9. Teruki O, Keiichi O. The safety of endoscopic day surgery

for colorectal polyps. Dig Endosc 2008;20:92-5. CrossRef

10. Ma WT, Mahadeva S, Kunanayagam S, Poi PJ, Goh KL.

Colonoscopy in elderly Asians: a prospective evaluation in

routine clinical practice. J Dig Dis 2007;8:77-81. CrossRef

11. Wong JC, Yau KK, Cheung HY, Wong DC, Chung CC,

Li MK. Towards painless colonoscopy: a randomized

controlled trial on carbon dioxide-insufflating colonoscopy.

ANZ J Surg 2008;78:871-4. CrossRef

12. Bayupurnama P, Nurdjanah S. The success rate of

unsedated colonoscopy examination in adult. Internet

Journal of Gastroenterology 2010;9:2.

13. Ylinen ER, Vehviläinen-Julkunen K, Pietilä AM, Hannila

ML, Heikkinen M. Medication-free colonoscopy—factors related to pain and its assessment. J Adv Nurs

2009;65:2597-607. CrossRef

14. Ho AK. When the numerator is zero: another lesson on

risk. Am Biol Teach 2009;71:531-3. CrossRef

15. Miller A, McGill D, Bassett ML. Anticoagulant therapy,

anti-platelet agents and gastrointestinal endoscopy. J

Gastroenterol Hepatol 1999;14:109-13. CrossRef

16. Dobbins C, DeFontgalland D, Duthie G, Wattchow DA. The

relationship of obesity to the complications of diverticular

disease. Colorectal Dis 2006;8:37-40. CrossRef

17. Ko CW, Riffle S, Shapiro JA, et al. Incidence of minor complications and time lost

from normal activities after screening or surveillance

colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;65:648-56. CrossRef

18. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. Gender differences in the reporting

of physical and somatoform symptoms. Psychosom Med

1998;60:150-5. CrossRef

19. Bretthauer M, Lynge AB, Thiis-Evensen E, Hoff G, Fausa O,

Aabakken L. Carbon dioxide insufflation in colonoscopy:

safe and effective in sedated patients. Endoscopy

2005;37:706-9. CrossRef

20. Welchman S, Cochrane S, Minto G, Lewis S. Systematic

review: the use of nitrous oxide gas for lower gastrointestinal

endoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010;32:324-33. CrossRef

21. Takahashi Y, Tanaka H, Kinjo M, Sakumoto K. Sedation-free

colonoscopy. Dis Colon Rectum 2005;48:855-9. CrossRef

Find HKMJ in MEDLINE: