Hong

Kong Med J 2018 Feb;24(1):11–7 | Epub 29 Dec 2017

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj176820

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Characteristics and clinical outcomes of living renal

donors in Hong Kong

YL Hong, MSc1; CH Yee, FHKAM (Surgery)1;

CB Leung, FHKAM (Surgery)2; Jeremy YC Teoh, FHKAM (Surgery)1;

Bonnie CH Kwan, FHKAM (Medicine)2; Philip KT Li, FHKAM

(Medicine)2; Simon SM Hou, FHKAM (Surgery)1; CF Ng,

FHKAM (Surgery)1

1 SH Ho Urology Centre, Department of

Surgery, Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese University of Hong Kong,

Shatin, Hong Kong

2 Division of Nephrology, Department of

Medicine and Therapeutics, Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese

University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof CF Ng (ngcf@surgery.cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: In Asia, few

reports are available on the outcomes for living renal donors. We report

the short- and long-term clinical outcomes of individuals following

living donor nephrectomy in Hong Kong.

Methods: We retrospectively

reviewed the characteristics and clinical outcomes of all living renal

donors who underwent surgery from January 1990 to December 2015 at a

teaching hospital in Hong Kong. Information was obtained from hospital

records and territory-wide electronic patient records.

Results: During the study

period, 83 individuals underwent donor nephrectomy. The mean (± standard

deviation) follow-up time was 12.0 ± 8.3 years, and the mean age at

nephrectomy was 37.3 ± 10.0 years. A total of 44 (53.0%), four (4.8%),

and 35 (42.2%) donors underwent living donor nephrectomy via an open,

hand-port assisted laparoscopic, and laparoscopic approach,

respectively. The overall incidence of complications was 36.6%, with

most being grade 1 or 2. There were three (9.4%) grade 3a complications;

all were related to open donor nephrectomy. The mean glomerular

filtration rate was 96.0 ± 17.5 mL/min/1.73 m2 at baseline

and significantly lower at 66.8 ± 13.5 mL/min/1.73 m2 at

first annual follow-up (P<0.01). The latest mean glomerular

filtration rate was 75.6% ± 15.1% of baseline. No donor died or

developed renal failure. Of the donors, 14 (18.2%) developed

hypertension, two (2.6%) had diabetes mellitus, and three (4.0%) had

experienced proteinuria.

Conclusion: The overall

perioperative outcomes are good, with very few serious complications.

The introduction of a laparoscopic approach has decreased perioperative

blood loss and also shortened hospital stay. Long-term kidney function

is satisfactory and no patients developed end-stage renal disease. The

incidences of new-onset medical diseases and pregnancy-related

complications were also low.

New knowledge added by this study

- The overall perioperative outcomes are good, with very few serious complications, among living renal donors. The introduction of a laparoscopic approach has decreased perioperative blood loss and also shortened hospital stay.

- Long-term kidney function was satisfactory and no patients developed end-stage renal disease (ESRD).

- The incidences of new-onset medical disease and pregnancy-related complications were also low.

- Medical practitioners should encourage relatives of patients with ESRD to consider the possibility of kidney donation.

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is the progressive

loss of kidney function over a period of time. End-stage renal disease

(ESRD) is the final stage of CKD. Patients with ESRD require renal

replacement therapy that includes haemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and

renal transplantation.

Currently, there are approximately 7000 patients on

various forms of renal replacement therapy being cared for in the public

sector in Hong Kong. As of 31 December 2016, 2047 patients were on the

renal transplant waiting list. Nonetheless, between 2007 and 2016, only 58

to 87 cadaveric renal transplants were performed in Hong Kong each year.1 With the long waiting list and low

number of cadaveric kidneys available, living donor renal transplant is

the only possible alternative. It offers advantages over other renal

replacement therapies, as it provides better long-term results, shortens

the waiting time for an organ, lowers the risk of complications or

rejection, and provides better quality of life after recovery. Despite

these advantages, only seven to 15 living donor transplants were performed

each year between 2007 and 2015 at the hospitals of the Hong Kong Hospital

Authority.1

One of the major fears of an individual who is

considering living organ donation concerns possible clinical outcomes.

Although studies show that living donors have a similar to or better life

expectancy than the general population, they are nevertheless at increased

risk of developing ESRD, hypertension, gestational hypertension, and

pre-eclampsia.2 3 4

In Hong Kong, few reports on the perioperative,

short-term, and long-term clinical outcomes are available, especially

those related to the minimally invasive surgical approach now employed for

donor nephrectomy. This study reports our observation of characteristics

of donors, and the short- and long-term clinical outcomes following living

donor nephrectomy in Hong Kong.

Methods

Study design

We retrospectively reviewed the characteristics and

short- and long-term clinical outcomes of all patients who underwent

living donor nephrectomy at the Prince of Wales Hospital in Hong Kong

between January 1990 and December 2015. Information was obtained from the

Clinical Management System that includes the majority of electronic

patient records—including consultation histories, operation records,

radiology results, laboratory results, and medication records—collected

and filed under the Hospital Authority since 2000. Medical records before

2000 and pregnancy-related information were reviewed manually by formally

trained medical students and cross-checked by a urologist, and retrieved

from the medical records of the involved patients.

The study was conducted in accordance with the

principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the

Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster

Clinical Research Ethics Committee, with the requirement of patient

informed consent waived because of its retrospective nature.

Study measures

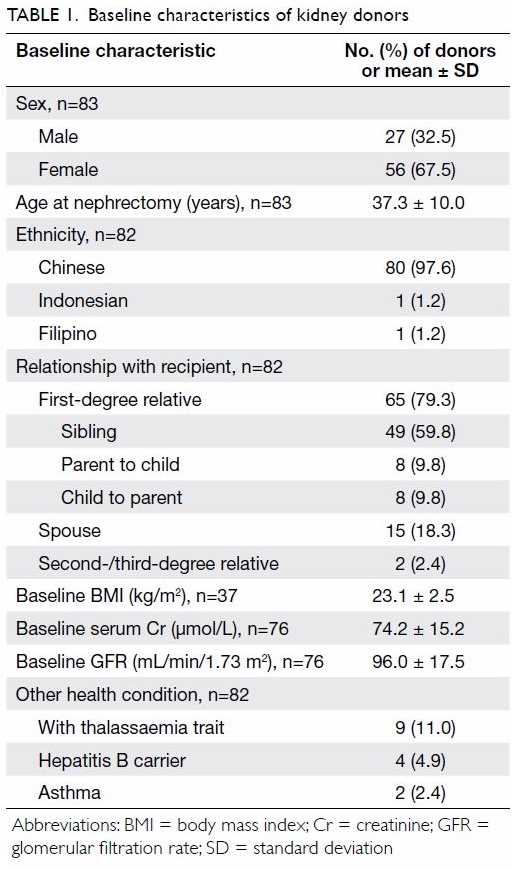

Baseline demographics including sex, age at

donation, ethnicity, relationship with recipient, diabetes mellitus

status, hypertension status, body mass index, and serum creatinine level

were obtained. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was derived from the serum

creatinine level using a modified equation from the Modification of Diet

in Renal Disease (MDRD) study.5

Operation details, including surgical approach, laterality of donated

kidney, operating time, warm ischaemia time, blood loss, and need for

transfusion were retrieved.

Short-term complications within 30 days of surgery

were classified according to the Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical

complications.6 Long-term outcomes

were also assessed, with particular reference to development of

hypertension, diabetes mellitus, renal stones, proteinuria, and renal

failure. Serial changes in GFR were also assessed.

For female donors, pregnancy-related variables were

recorded and included any pregnancy after surgery, records of

pregnancy-related hydronephrosis, pregnancy-related urinary tract

infection, pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes mellitus, gestational

hypertension, and any fetal loss.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using the

SPSS (Windows version 23.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States).

Categorical variables were presented in counts and percentages while

continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Outcomes

following open and laparoscopic techniques were compared by Chi squared

test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, and independent t

test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. Paired t

test or Wilcoxon rank sum test, whichever was appropriate, was used to

evaluate the pre- and post-difference in GFR. A P value of <0.05 was

considered statistically significant. Missing data were excluded from

analysis.

Results

Donor characteristics

Between 1 January 1990 and 31 December 2015, a

total of 83 donors underwent unilateral nephrectomy at the Prince of Wales

Hospital. In one donor, records could not be traced, with only information

about the sex, age at nephrectomy, and type of surgical technique.

Of the 83 donors, 56 (67.5%) were female. The mean

age at nephrectomy was 37.3 ± 10.0 years. The majority were Chinese

(97.6%) and a first-degree relative of the recipient (79.3%). None had

hypertension or diabetes mellitus. The mean preoperative GFR was 96.0 ±

17.5 mL/min/1.73 m2. Nine (11.0%) donors had thalassaemia

trait, four (4.9%) had hepatitis B, and two (2.4%) had asthma (Table

1).

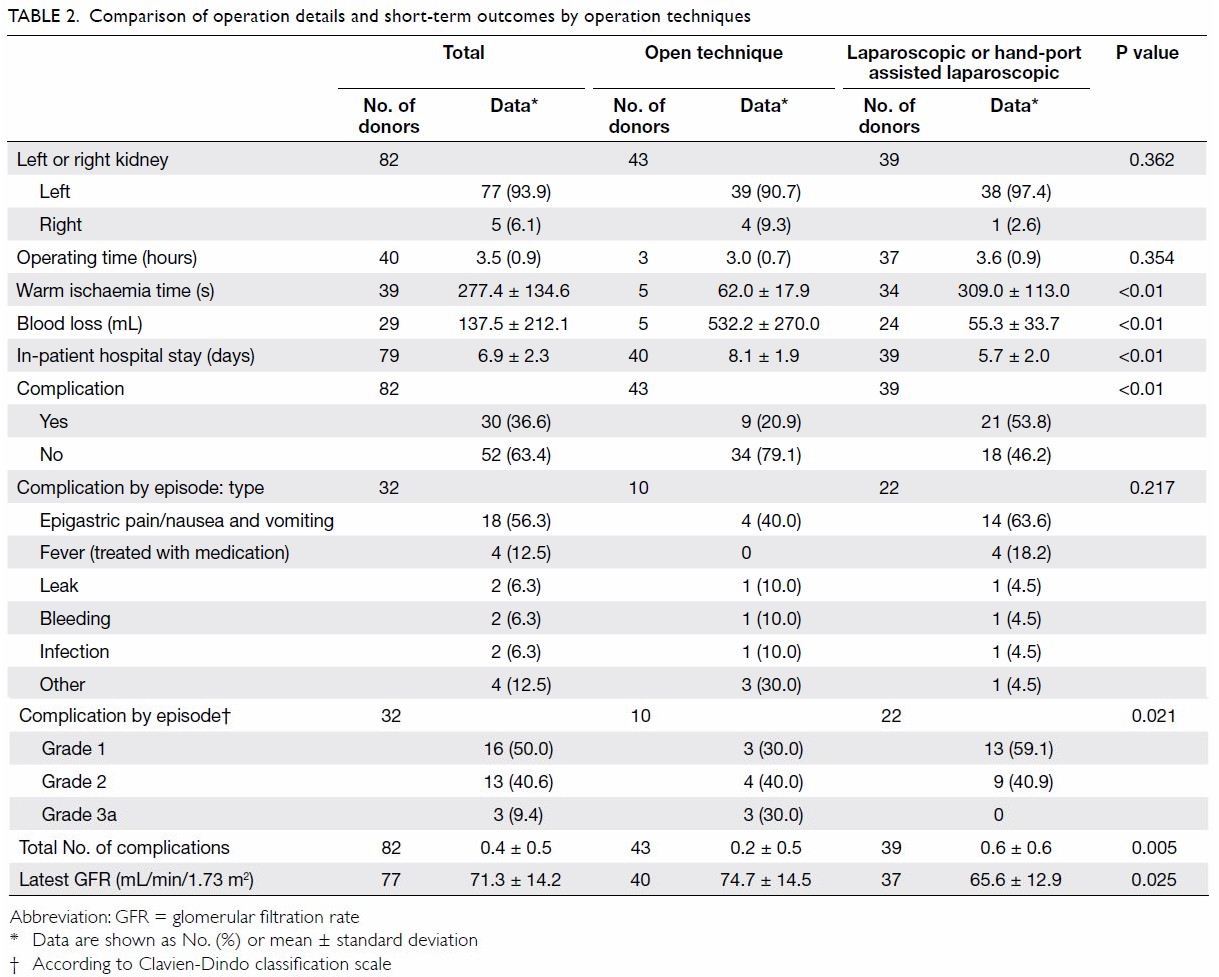

Operation details and short-term outcomes

Around half (n=44, 53.0%) of the donors underwent

open living donor nephrectomy, as this was the only technique used at our

centre until 2002. After 2002, a hand-port assisted laparoscopic approach

(n=4, 4.8%) and later a laparoscopic approach (n=35, 42.2%) were adopted.

In most instances, the left kidney was donated (n=77, 93.9%) [Table

2].

Comparing laparoscopic or hand-port assisted

laparoscopic living donor nephrectomy (LDN) with open donor nephrectomy

(ODN), LDN was associated significantly with longer warm ischaemia time

(309.0 ± 113.0 s vs 62.0 ± 17.9 s; P<0.01), less blood loss (55.3 ±

33.7 mL vs 532.2 ± 270.0 mL; P<0.01), and shorter hospital stay (5.7 ±

2.0 days vs 8.1 ± 1.9 days; P<0.01). In addition, LDN was associated

significantly with more short-term complications (53.8% vs 20.9%;

P<0.01). The most commonly experienced complication was epigastric

pain/nausea and vomiting (n=18, 56.3%), followed by fever requiring

medication (n=4, 12.5%). Most complications were grade 1 on the

Clavien-Dindo classification scale (n=16, 50.0%), only three (9.4%) were

grade 3a and all were related to ODN. The grade 3a complications were

wound dehiscence that required a second operation for re-suturing,

persistent pancreatic fluid discharge that required insertion of a

pancreatic stent, and pneumothorax with chest drain inserted.

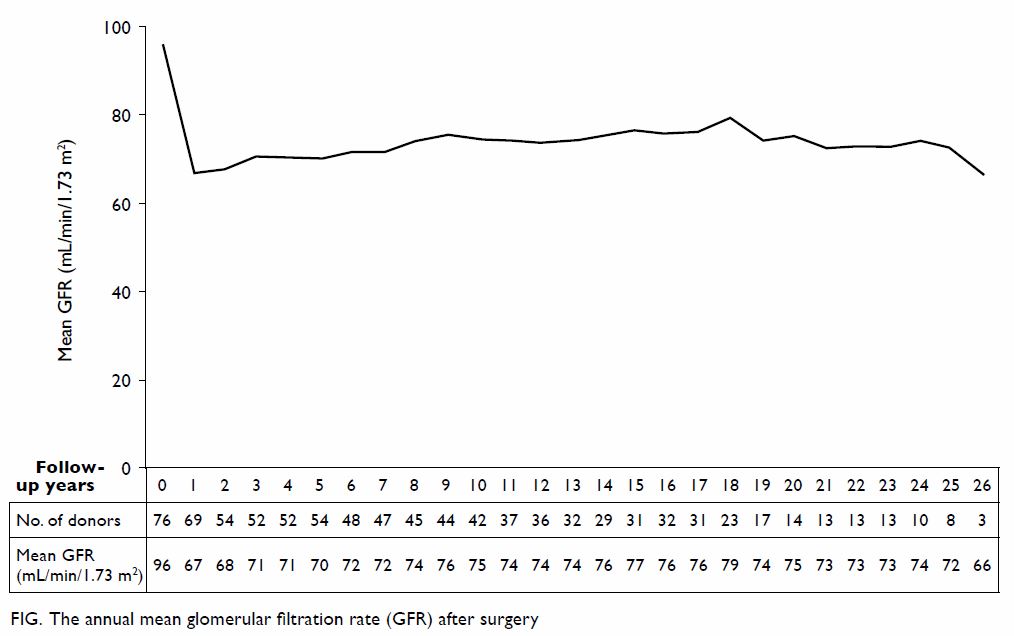

Long-term outcomes

The mean follow-up time was 12.0 ± 8.3 years. The

mean GFR was 96.0 ± 17.5 mL/min/1.73 m2 at baseline and it

dropped significantly to 66.8 ± 13.5 mL/min/1.73 m2 at 1-year

follow-up (P<0.01). The GFR then gradually improved until 8 years after

surgery and became stable (Fig). Of 73 living donors with at least one

follow-up (mean follow-up time, 12.0 ± 8.2 years) and baseline serum

creatinine level available, the latest GFR was 75.6% ± 15.1% of baseline

GFR with the mean latest GFR being 71.3 ± 14.2 mL/min/1.73 m2.

The mean GFR was 70.4% ± 12.3% of baseline level 1 year after surgery.

Comparison of latest GFR with that 1 year after surgery revealed that it

was stable (± 10% change) in 23 (39.0%) of 59 patients and higher (>10%

increment) in 29 (49.2%) patients. None of the donors had died or

developed ESRD. Fourteen (18.2%) donors developed hypertension, two (2.6%)

had diabetes mellitus, and three (4.0%) had experienced proteinuria (Table

3).

Pregnancy-related complications

Of 56 female donors, 11 (19.6%) became pregnant

after kidney donation: 17 pregnancies were reported. None of the pregnant

donors experienced gestational hydronephrosis or gestational hypertension.

Three donors each had gestational diabetes mellitus, pre-eclampsia, and

post-delivery urinary tract infection. Two donors had experienced fetal

loss, one in the first trimester and another one at an unknown gestational

age (Table 4).

Discussion

Postoperative morbidity and mortality are the prime

concerns when making a decision about kidney donation. Our results confirm

that living donor nephrectomy is a relatively safe procedure, with a low

incidence of major complications and mortality. In addition, the incidence

of developing any other major disease was not particularly high in our

series. This form of renal replacement therapy should be further promoted

in Hong Kong to benefit more people with ESRD.

Results from previous studies have shown that

living renal donors have a similar to or better life expectancy than the

general population.7 8 9 10 Mjøen et al,11

however, reported that compared with healthy matched individuals, living

renal donors had an increased risk of death. In Hong Kong, Chu et al12 reported one death related to multiple myeloma among

95 living renal donors with active follow-up and a mean follow-up period

of 13.4 years. There were no deaths recorded in our study with a mean

follow-up of 12 years.

Long-term renal function is another major concern

of renal donors. Our results revealed that 1 year after living donor

nephrectomy, the mean GFR of the kidney donors dropped significantly from

96.0 ± 17.5 mL/min/1.73 m2 at baseline to 66.8 ± 13.5

mL/min/1.73 m2. Nonetheless, it then gradually improved. This

is probably partly related to the adaptation of the remaining kidney with

hyper-filtration. From our series, the mean GFR was 70.4% ± 12.3% of

baseline level 1 year after surgery but improved to 75.6% ± 15.1% of

baseline level at the last follow-up. In the majority (88.2%) of donors,

the last available GFR was static or higher than that 1 year after

donation. This is comparable with the report of Rook et al13 in which GFR usually reached 64% ± 7% of the

pre-donation level 1 year after donation.

Despite these changes in GFR, ESRD in renal donors

is very rare, with an incidence of less than 0.5% in 15 years after

donation.11 14 15 Ibrahim

et al8 reported that survival and

risk of ESRD in kidney donors appeared to be similar to those in the

general population. Our study and that of Chu et al12 observed no ESRD in local kidney donors.

The effect of kidney donation on the development of

hypertension is controversial. Although reports suggest that the incidence

of hypertension among kidney donors increases,16

17 18

19 others have not confirmed this

observation.20 21 22 23 24 In Hong

Kong, the prevalence of hypertension in the general population was 12.6%

in 2014,25 which is lower than our

reported figure of 18.2%. With the progression of time after surgery,

however, the prevalence of hypertension among living donors is expected to

increase as age is a known influence in hypertension. Without a comparable

control group, we cannot conclude if there is any actual discrepancy in

the prevalence of hypertension among living donors compared with the

general population.

Young female potential donors may have concerns

about the impact of kidney donation on any future pregnancy. Garg et al4 reported that gestational

hypertension or pre-eclampsia was more common among living donors than

non-donors. Although our study showed an alarmingly high percentage (11%)

of pre-eclampsia and absence of gestational hypertension, the small sample

size (11 donors reported one or more pregnancies) undermines the ability

to infer the actual percentage.

Perioperative complications may also deter

potential living donors. Based on the US data, Lentine et al26 reported that 16.8% of donors experience a

perioperative complication; most commonly gastrointestinal (4.4%). Our

study showed a higher complication rate of 36.6%, with epigastric pain or

nausea and vomiting being the major complication (56.3%). We further

examined the techniques used and established that the complication rates

of 20.9% or 53.8% respectively in donors who underwent ODN or LDN were

significantly different (P<0.01). Despite the above mean complication

rates, all complications of LDN were mild and of grade 1 or 2 according to

the Clavien-Dindo classification, while three patients who underwent ODN

had grade 3a complications. This is contrary to the majority of previous

findings that suggest a lower perioperative complication rate for LDN and

increased risk of more serious complications than during an ODN,27 although other indicators such as longer warm

ischaemia time, less blood loss, and shorter hospital stays were still in

line with previous findings. Further analysis of the differences between

our local data and those of previous studies is warranted.

This study has several limitations. First, this was

a retrospective study and the total number of living donors was

restricted. Second, data quality could not be controlled and some data

were incomplete, in particular for the obstetric records at other

hospitals. Some data were also lost either because records were too old

and pre-dated the electronic system or donors were no longer followed up

at our centre. The oldest record included in the study was from 1990. At

that time, record keeping was not always accurate, resulting in some

baseline records from the early 1990s being missing. For example, the

baseline GFR level of seven (8.4%) patients was not found, and might have

affected the overall data quality as well as the analysis and conclusion.

Third, although the urologist endeavoured to ensure accurate data entry,

initial interpretation of the raw records was by medical students so

certain inaccuracies might have occurred. Lastly, it is known that GFR

might be underestimated when derived from the MDRD equation.

Conclusion

Living donor kidney transplantation is an important

approach to improve the quality of life of patients with ESRD. Good short-

and long-term outcome for kidney donors is important for promoting kidney

donation. Our results suggest that the overall perioperative outcomes are

good, with only very few serious (grade III) complications after surgery,

occurring following an open approach. Long-term kidney function of donors

was satisfactory and no patients developed ESRD. Although we had no

control arm in our study, the overall incidences of new-onset medical

diseases and pregnancy-related complications were low. The introduction of

a laparoscopic approach for kidney harvesting has helped to decrease blood

loss during surgery and also shorten hospital stay. Based on this

encouraging result, relatives of patients with ESRD should be encouraged

to consider the possibility of kidney donation.

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks are given to Ms Karen Man-ting Chuk,

Ms Tracy Lok-sze Chiu, Mr Wing-tung Leung, and Mr On-wa Ng for assisting

with the data collection.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of

interest.

References

1. Statistics (Milestones of Hong Kong

organ transplantation): organ donation. Available from:

http://www.organdonation. gov.hk/eng/statistics.html. Accessed 27 Dec

2017.

2. Reese PP, Boudville N, Garg AX. Living

kidney donation: outcomes, ethics, and uncertainty. Lancet

2015;385:2003-13. Crossref

3. Delanaye P, Weekers L, Dubois BE, et al.

Outcome of the living kidney donor. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012;27:41-

50. Crossref

4. Garg AX, Nevis IF, Mcarthur E, et al.

Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia in living kidney donors. N Engl

J Med 2015;372:124-33. Crossref

5. Levey AS, Greene T, Kusek JW, Beck GJ. A

simplified equation to predict glomerular filtration rate from serum

creatinine. J Am Soc Nephrol 2000;11:155A0828.

6. Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA.

Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation

in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg

2004;240:205-13. Crossref

7. Segev DL, Muzaale AD, Caffo BS, et al.

Perioperative mortality and long-term survival following live kidney

donation. JAMA 2010;303:959-66. Crossref

8. Ibrahim HN, Foley R, Tan L, et al.

Long-term consequences of kidney donation. N Engl J Med 2009;360:459-69. Crossref

9. Okamoto M, Akioka K, Nobori S, et al.

Short- and long-term donor outcomes after kidney donation: analysis of 601

cases over a 35-year period at Japanese single center. Transplantation

2009;87:419-23. Crossref

10. Garg AX, Meirambayeva A, Huang A, et

al. Cardiovascular disease in kidney donors: matched cohort study. BMJ

2012;344:e1203. Crossref

11. Mjøen G, Hallan S, Hartmann A, et al.

Long-term risks for kidney donors. Kidney Int 2014;86:162-7. Crossref

12. Chu KH, Poon CK, Lam CM, et al.

Long-term outcomes of living kidney donors: a single centre experience of

29 years. Nephrology (Carlton) 2012;17:85-8. Crossref

13. Rook M, Hofker HS, van Son WJ, Homan

van der Heide JJ, Ploeg RJ, Navis GJ. Predictive capacity of pre-donation

GFR and renal reserve capacity for donor renal function after living

kidney donation. Am J Transplant 2006;6:1653-9. Crossref

14. Muzaale AD, Massie AB, Wainwright J,

McBride MA, Wang M, Segev DL. Long-term risk of ESRD attributable to live

kidney donation: matching with healthy non-donors. Am J Transplant

2013;13:204-5.

15. Fehrman-Ekholm I, Nordén G, Lennerling

A, et al. Incidence of end-stage renal disease among live kidney donors.

Transplantation 2006;82:1646-8. Crossref

16. Kasiske BL, Ma JZ, Louis TA, Swan SK.

Long-term effects of reduced renal mass in humans. Kidney Int

1995;48:814-9. Crossref

17. Gossmann J, Wilhelm A, Kachel HG, et

al. Long-term consequences of live kidney donation follow-up in 93% of

living kidney donors in a single transplant center. Am J Transplant

2005;5:2417-24. Crossref

18. Garg AX, Prasad GV, Thiessen-Philbrook

HR, et al. Cardiovascular disease and hypertension risk in living kidney

donors: an analysis of health administrative data in Ontario, Canada.

Transplantation 2008;86:399-406. Crossref

19. Doshi MD, Goggins MO, Li L, Garg AX.

Medical outcomes in African American live kidney donors: a matched cohort

study. Am J Transplant 2012;13:111-8. Crossref

20. Fehrman-Ekholm I, Dunér F, Brink B,

Tydén G, Elinder CG. No evidence of accelerated loss of kidney function in

living kidney donors: results from a cross-sectional follow-up.

Transplantation 2001;72:444-9. Crossref

21. Macdonald D, Kukla AK, Ake S, et al.

Medical outcomes of adolescent live kidney donors. Pediatric Transplant

2014;18:336-41. Crossref

22. Janki S, Klop KW, Dooper IM, Weimar W,

Ijzermans JN, Kok NF. More than a decade after live donor nephrectomy: a

prospective cohort study. Transpl Int 2015;28:1268-75. Crossref

23. Tavakol MM, Vincenti FG, Assadi H, et

al. Long-term renal function and cardiovascular disease risk in obese

kidney donors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;4:1230-8. Crossref

24. El-Agroudy AE, Wafa EW, Sabry AA, et

al. The health of elderly living kidney donors after donation. Ann

Transplant 2009;14:13-9.

25. Census and Statistics Department, Hong

Kong SAR Government. Thematic Household Survey Report No. 58. Available

from: http://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/ B11302582015XXXXB0100.pdf.

Accessed 28 Oct 2016.

26. Lentine KL, Lam NN, Axelrod D, et al.

Perioperative complications after living kidney donation: a national

study. Am J Transplant 2016;16:1848-57. Crossref

27. Fonouni H, Mehrabi A, Golriz M, et al.

Comparison of the laparoscopic versus open live donor nephrectomy: an

overview of surgical complications and outcome. Langenbecks Arch Surg

2014;399:543-51. Crossref