Depression and anxiety among university students in Hong Kong

Hong

Kong Med J 2018 Oct;24(5):466–72 | Epub 24 Sep 2018

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj176915

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Depression and anxiety among university students in

Hong Kong

Kevin WC Lun, CK Chan, Patricia KY Ip, Samantha YK

Ma, WW Tsai, CS Wong, Christie HT Wong, TW Wong, D Yan

Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of

Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Mr Kevin WC Lun (lunkwc@gmail.com)

Abstract

Introduction: Entry into

tertiary education is a critical juncture where adolescents proceed to

adulthood. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of depression

and anxiety, and factors associated with such symptoms, among university

undergraduate students in Hong Kong.

Methods: A cross-sectional

questionnaire study was employed. A total of 1200 undergraduate students

from eight University Grants Committee–funded universities were invited

to complete three sets of questionnaires, including the 9-item patient

health questionnaire for screening of depressive symptoms, the 7-item

generalised anxiety disorder scale for screening of anxiety symptoms,

and a socio-demographic questionnaire.

Results: Among the valid

responses (n=1119) analysed, 767 (68.5%) respondents indicated mild to

severe depressive symptoms, which were associated with mild to severe

anxiety symptoms. Several lifestyle and psychosocial variables,

including regular exercise, self-confidence, satisfaction with academic

performance, and optimism towards the future were inversely related with

mild to severe depressive symptoms. A total of 599 (54.4%) respondents

indicated mild to severe anxiety symptoms, which were associated with

level of academic difficulty. Satisfaction with friendship, sleep

quality, and self-confidence were inversely associated with mild to

severe anxiety symptoms.

Conclusion: More than 50% of

respondents expressed some degree of depressive and anxiety symptoms

(68.5% and 54.4%, respectively). Approximately 9% of respondents

exhibited moderately severe to severe depressive symptoms; 5.8%

exhibited severe anxiety symptoms. Respondents reporting regular

exercise, higher self-confidence, and better satisfaction with both

friendship and academic performance had fewer depressive and anxiety

symptoms.

New knowledge added by this study

- Up to 9% of university students in Hong Kong exhibit moderately severe to severe depressive symptoms.

- Up to 5.8% of university students in Hong Kong exhibit severe anxiety symptoms.

- Respondents reporting regular exercise, higher self-confidence, and better satisfaction with both friendship and academic performance had fewer depressive and anxiety symptoms.

- Health care workers and organisations such as universities should be aware of potential depression and anxiety among university undergraduate students.

- Adolescents and young adults in Hong Kong should be educated, to raise social awareness of depression and anxiety among university undergraduate students.

Introduction

Recently, an increased incidence of suicide among

students has triggered immense public concern regarding the mental health

of adolescents and young adults. In 2014, there were 52 suicides in the

age-group 15 to 24 years. The number of suicides in this age-group

increased in subsequent years to 68 in 2015 and 75 in 2016.1 A report from the Centre for Health Protection in Hong

Kong showed that, in 2012, the prevalences of mild, moderate, and severe

depressive symptoms in adolescents and children were 36.4%, 14.7%, and

4.2%, respectively.2 The Population

Health Survey 2003/2004 conducted collaboratively by the Department of

Health and the Department of Community Medicine of the University of Hong

Kong revealed that the median score for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

was highest in those aged 25 to 34 years, whereas the median score for the

Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale was highest in those

aged 15 to 34 years.3 A web-based

survey targeting first-year students receiving tertiary education in Hong

Kong concluded that, in 2006, the prevalence of depression was 20.9%,

while that of anxiety was 41.2%.4

Another recent study, the Hong Kong Mental Morbidity Survey,5 revealed that the most common mental problem in Hong

Kong was mixed anxiety and depressive disorder; moreover, there was a

strong association between anxiety symptoms and depressive symptoms.

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

of Mental Disorders, published by the American Psychiatric Association,

major depressive disorder is defined as the presence of five or more of

the listed symptoms for most of the days during the same 2-week period; at

least one of the symptoms must be either depressed mood or loss of

interest or pleasure. Notably, these symptoms should reflect a change from

previous functioning. Generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) is characterised

by excessive worries that cause distress and interfere with psychosocial

functioning. These worries frequently happen without precipitants, exhibit

longer durations, and are accompanied by three or more of the six listed

additional symptoms.

Various factors associated with major depressive

disorder and GAD have been identified, including alcohol use, illicit drug

use, tobacco use, and level of physical activity.6

However, evidence for an association between academic pressure and these

two psychiatric disorders remains unknown among university undergraduate

students in Hong Kong. We aimed to provide an update regarding the

prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms experienced by undergraduate

students in Hong Kong, and to identify factors associated with these

symptoms.

Methods

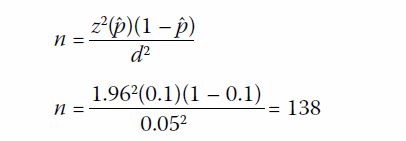

Full-time undergraduate students of the eight

universities in Hong Kong that are funded by the University Grants

Committee (UGC) were the target participants in this study. A

cross-sectional study design was employed and the target number of

students to be enrolled from each university was 150; the total target

number of students to be recruited was 1200.

The inclusion criteria for this study were as

follows: full-time undergraduate students in the eight UGC-funded

universities who were ≥18 years, were able to understand the consent,

provide a valid oral consent, comprehend the questionnaire, and had not

previously participated in this research. Students who failed to fulfil

all inclusion criteria were excluded from the study.

Convenience sampling was employed. Questionnaires

were distributed at popular locations within all eight university campuses

on school days in September and October 2016. Participants were asked to

complete three sets of questionnaires, including the 9-item Patient Health

Questionnaire (PHQ-9) for screening of depressive symptoms, the 7-item GAD

scale (GAD-7) for screening of anxiety symptoms, and a socio-demographic

questionnaire to identify factors associated with depressive and anxiety

symptoms.7 8 When completed questionnaires were being returned,

respondents were reminded that they would not be able to withdraw from the

study after returning the questionnaires, as the questionnaires did not

contain any personal identifying information to allow individual

retrieval.

The PHQ-9 was adopted to screen for depressive

symptoms in this study. Both Chinese and English versions were provided.

The PHQ-9 has been shown to be a valid and reliable tool for assessing

depressive symptoms in the Hong Kong general population.7 8 Another study

showed that the PHQ-9 was a useful tool to detect both major depression

and subthreshold depression.9

According to the PHQ-9, a score of <5 was defined as none-minimal

depressive symptoms, score of 5 to 9 as mild, score of 10 to 14 as

moderate, score of 15 to 19 as moderately severe, and score of ≥20 as

severe.

The GAD-7 is a practical self-report anxiety

questionnaire that is generally used in out-patient and primary care

settings for referral to a psychiatrist to confirm the diagnosis of GAD.

Both Chinese and English versions were available. The adoption of GAD-7 in

this study was due to its good reliability, as well as its criteria,

construct, and factorial and procedural validity.10

11 According to the GAD-7, a score

of <5 was defined as none-minimal anxiety symptoms, score of 5 to 9 as

mild, score of 10 to 14 as moderate, and score of ≥15 as severe.

Descriptive analysis was performed to summarise the

demographics and statuses of depressive and anxiety symptoms of the

respondents. A binary logistic regression was conducted to ascertain the

effects of various covariates on the odds of exhibiting mild to severe

depressive symptoms, on the basis of PHQ-9 results. A PHQ-9 score of <5

was defined as no depressive symptoms, while a score of ≥5 was defined as

mild to severe depressive symptoms. Another binary logistic regression was

used to ascertain the effects of multiple covariates on the odds that

participants would exhibit mild to severe anxiety symptoms, on the basis

of GAD-7 results. A GAD-7 score of <5 was defined as no anxiety

symptoms, while a score of ≥5 was defined as mild to severe anxiety

symptoms. A P value of <0.05 was regarded as a significant difference.

Results

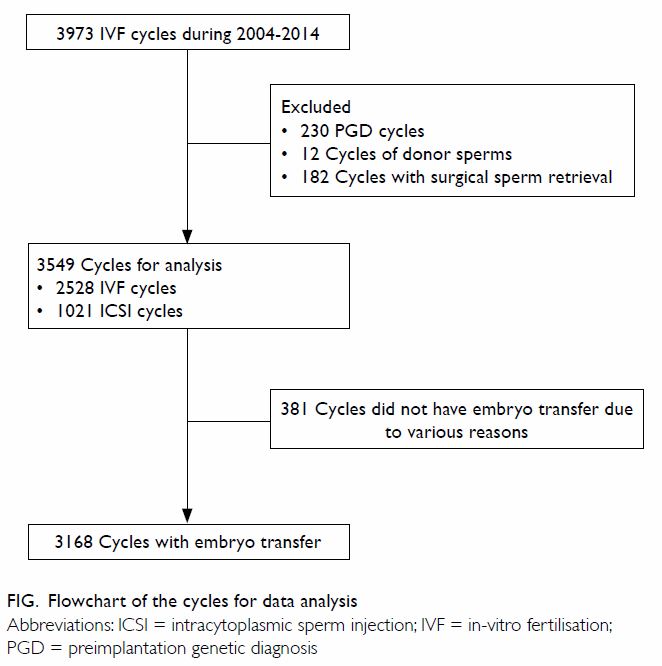

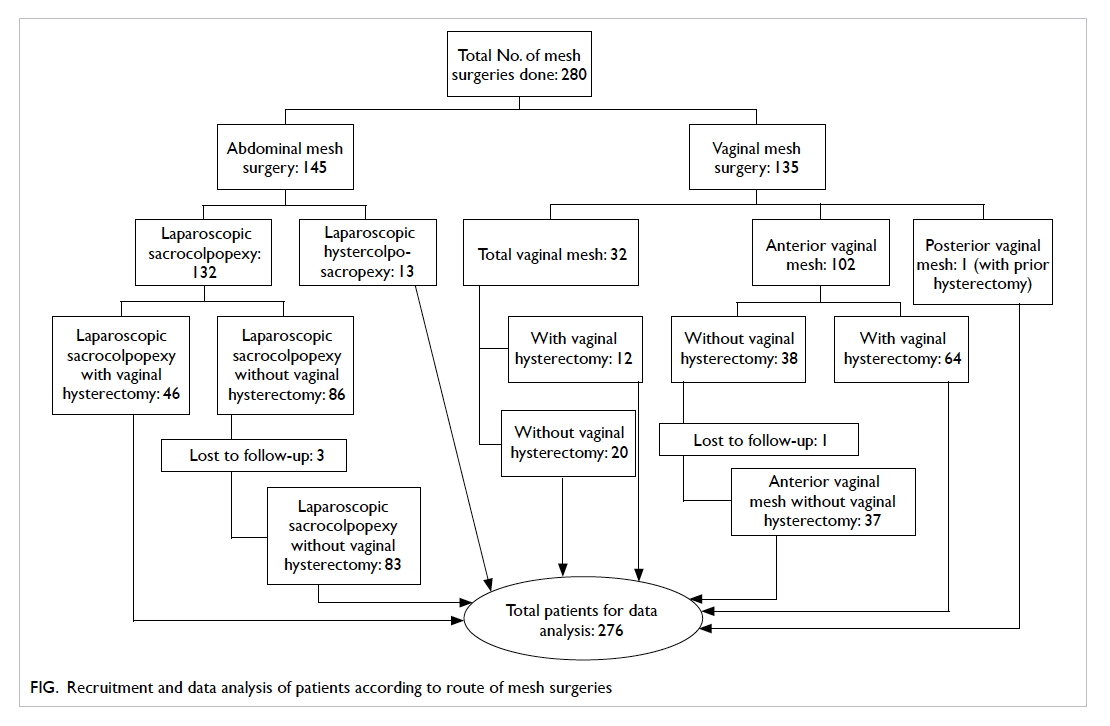

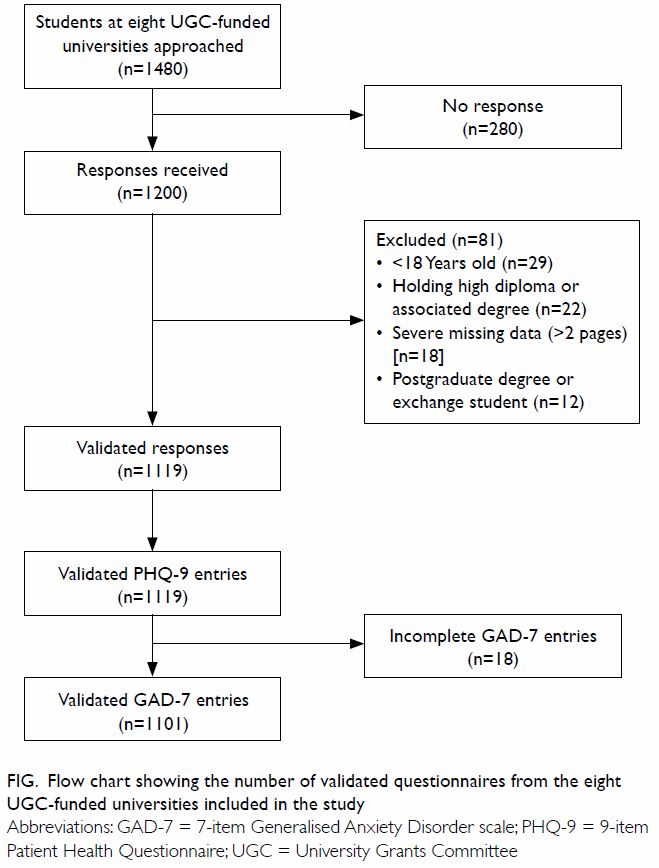

In total, 1480 undergraduate students from the

eight UGC-funded universities were approached from 6 September 2016 to 3

October 2016. From these, 1200 completed questionnaires were collected,

for a response rate of 81.1%. A total of 81 students did not meet at least

one of the inclusion criteria and their responses were subsequently

excluded from analysis (Fig). The remaining 1119 students fulfilled all

inclusion criteria and their responses were analysed by SPSS (Mac version

24; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States).

Figure. Flow chart showing the number of validated questionnaires from the eight UGC-funded universities included in the study

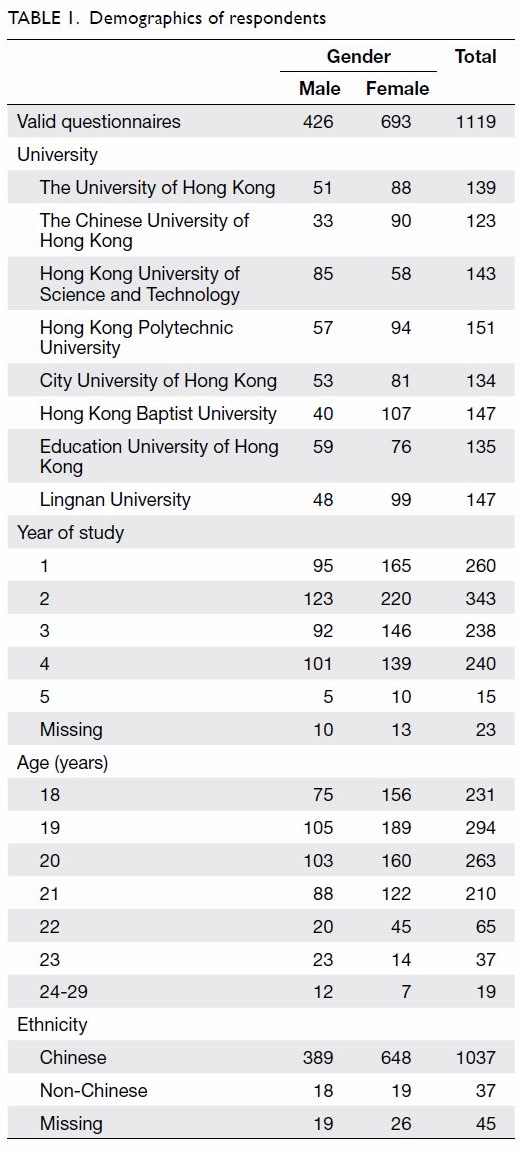

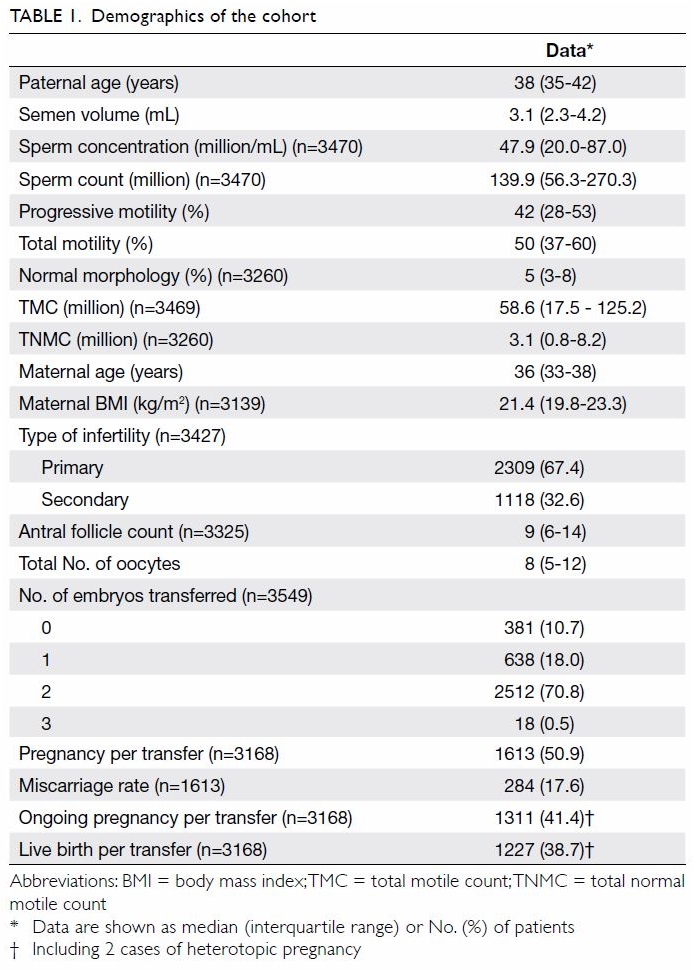

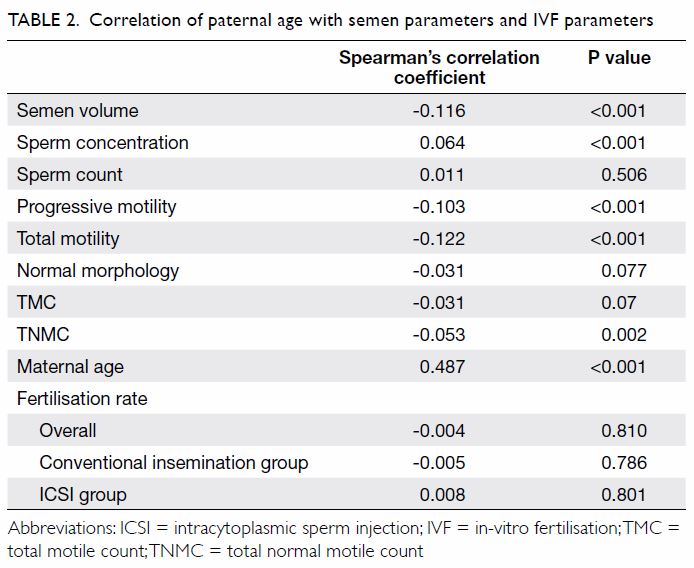

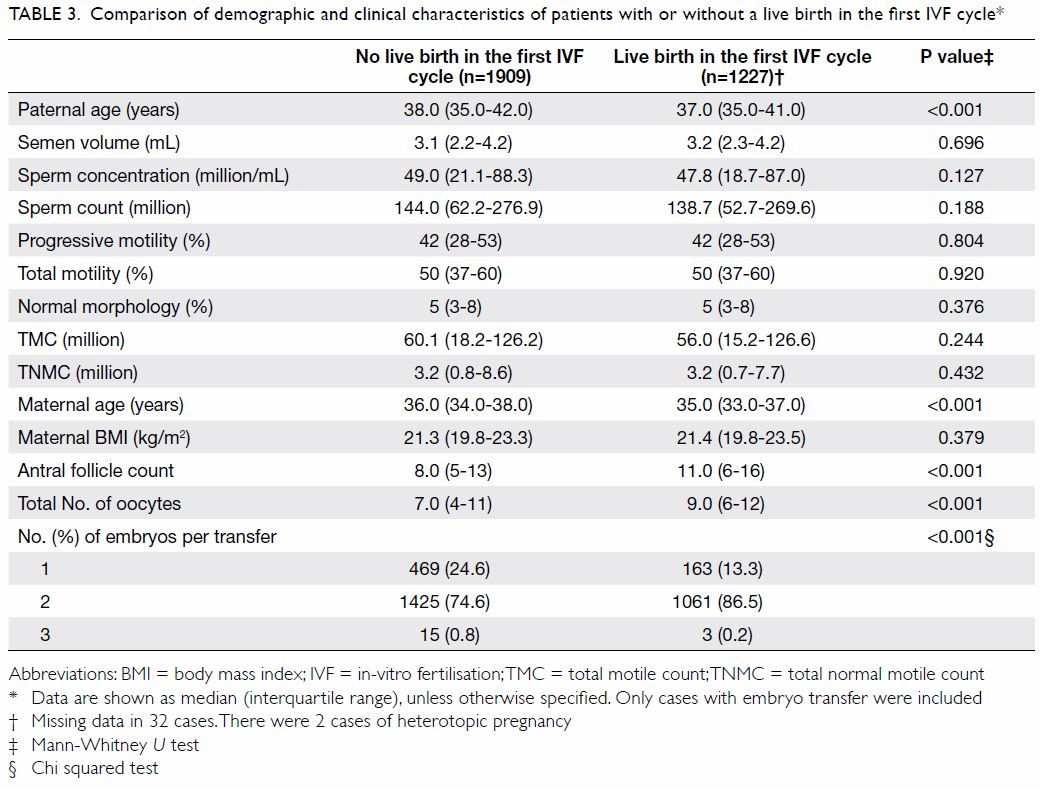

The mean (standard deviation) age of the

respondents was 19.81 (1.48) years (range, 18-29 years). Among the

respondents, 426 (38.1%) were male and 693 (61.9%) were female. Most

respondents were Chinese (92.7%). The respondents’ demographics are shown

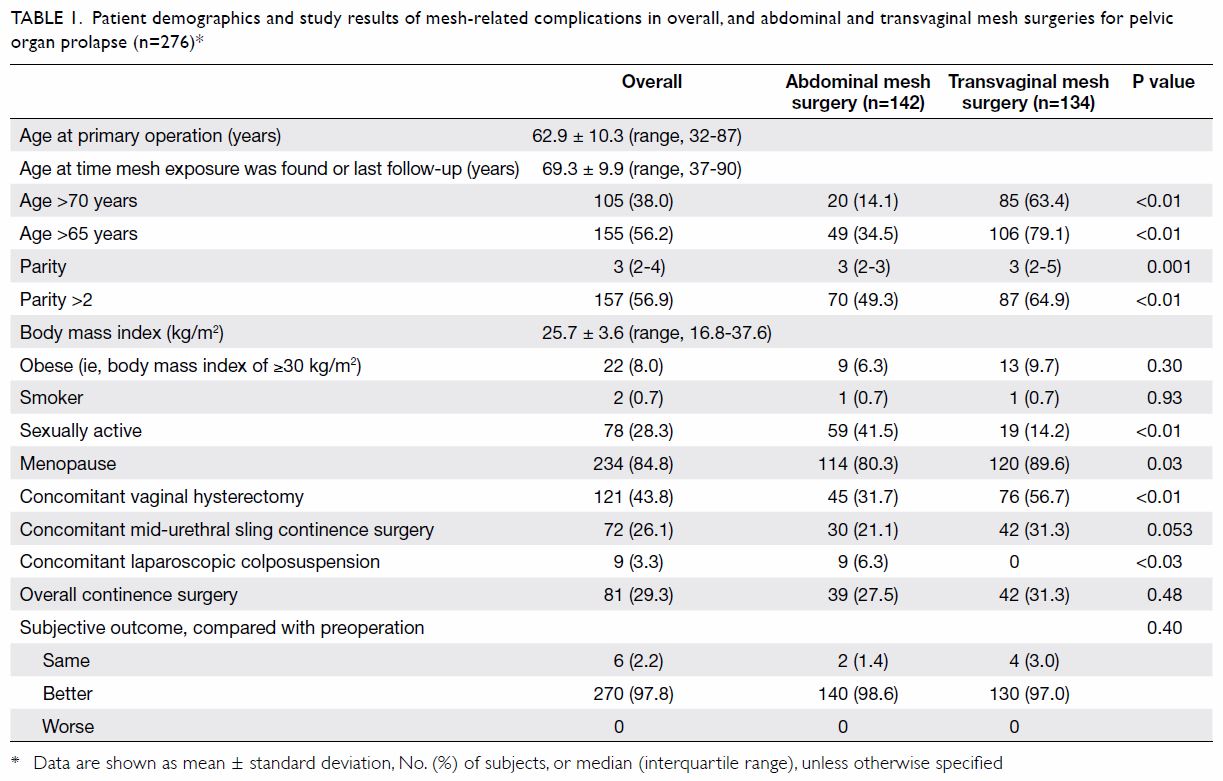

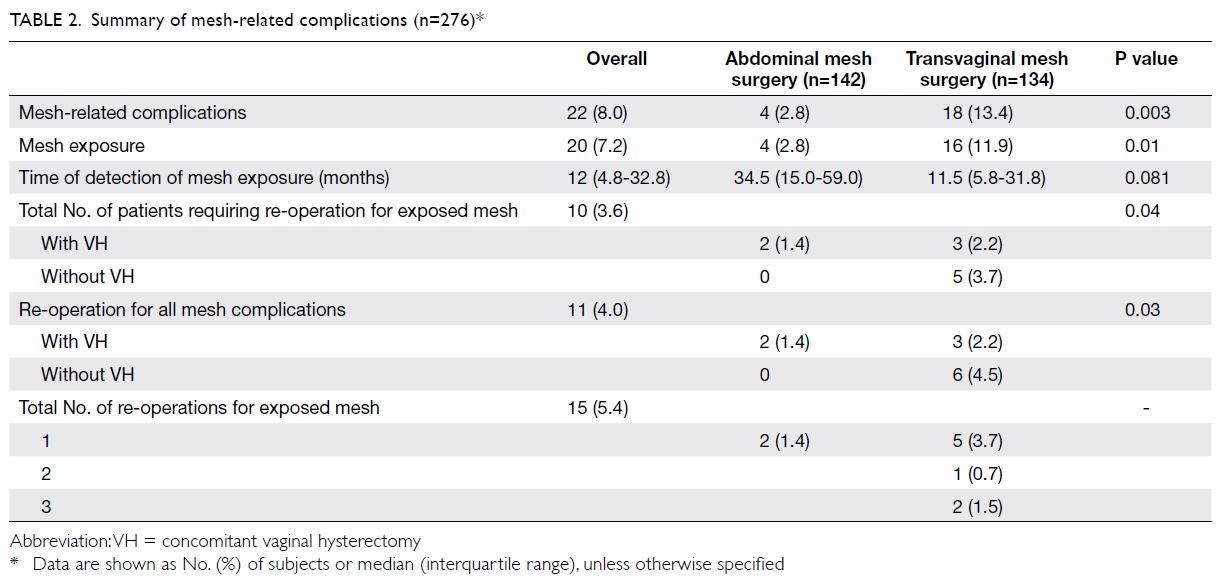

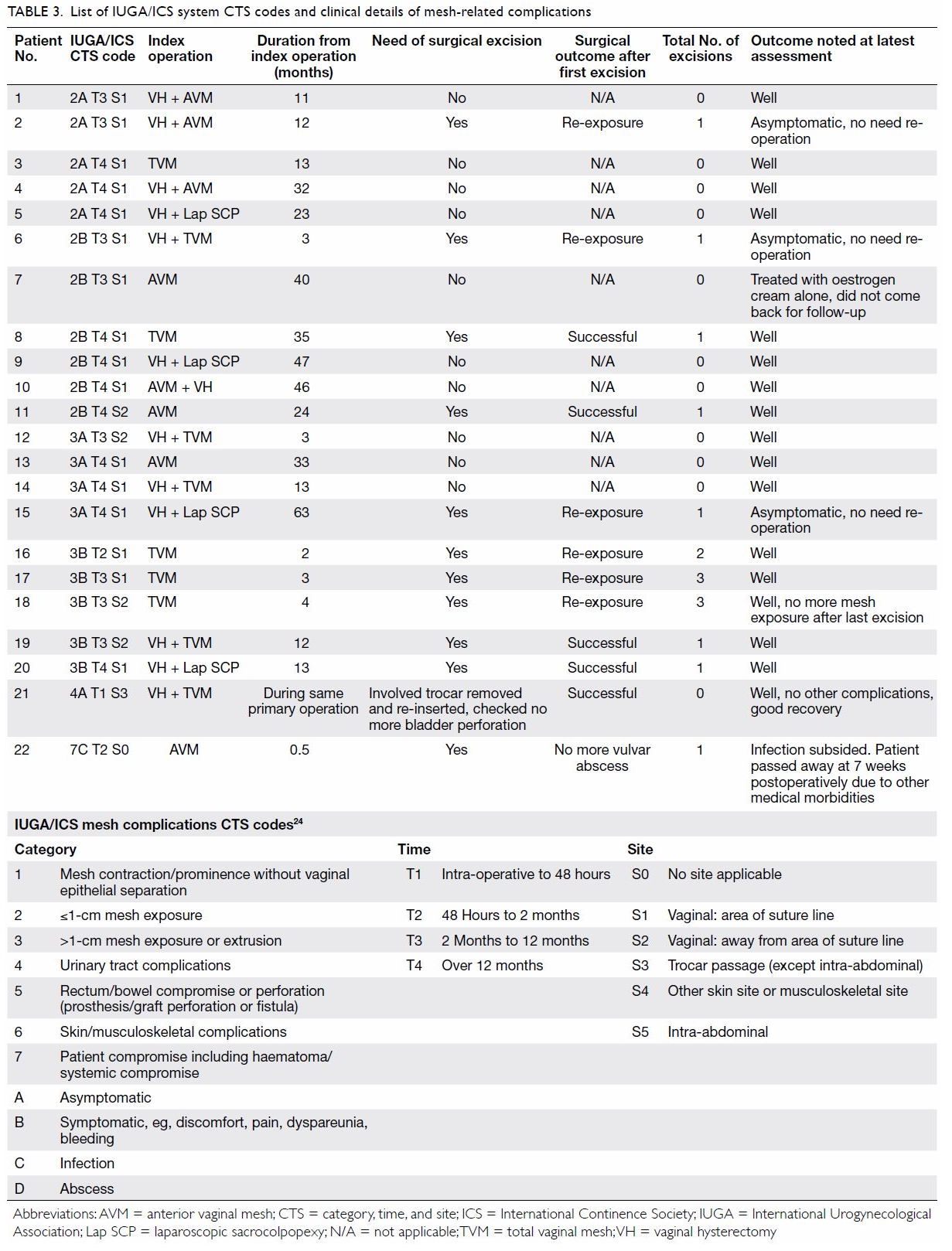

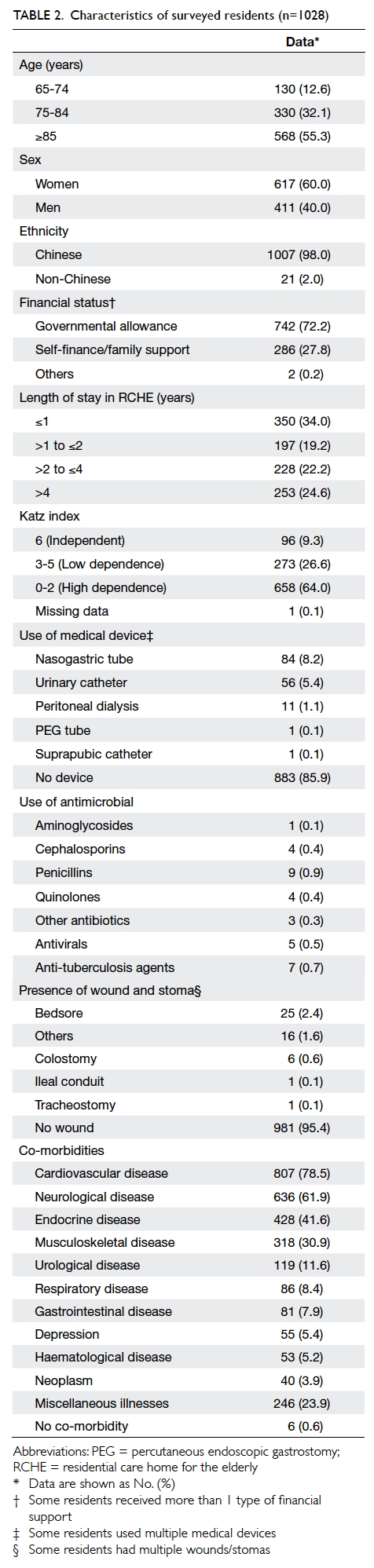

in Table 1.

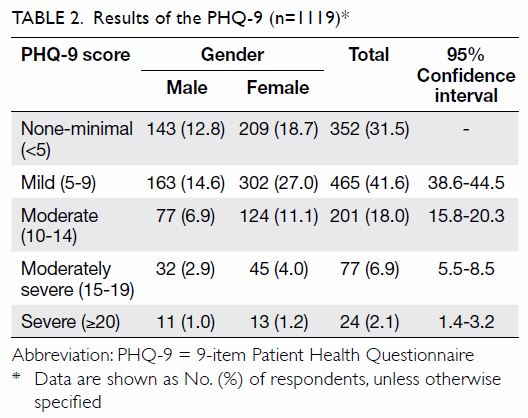

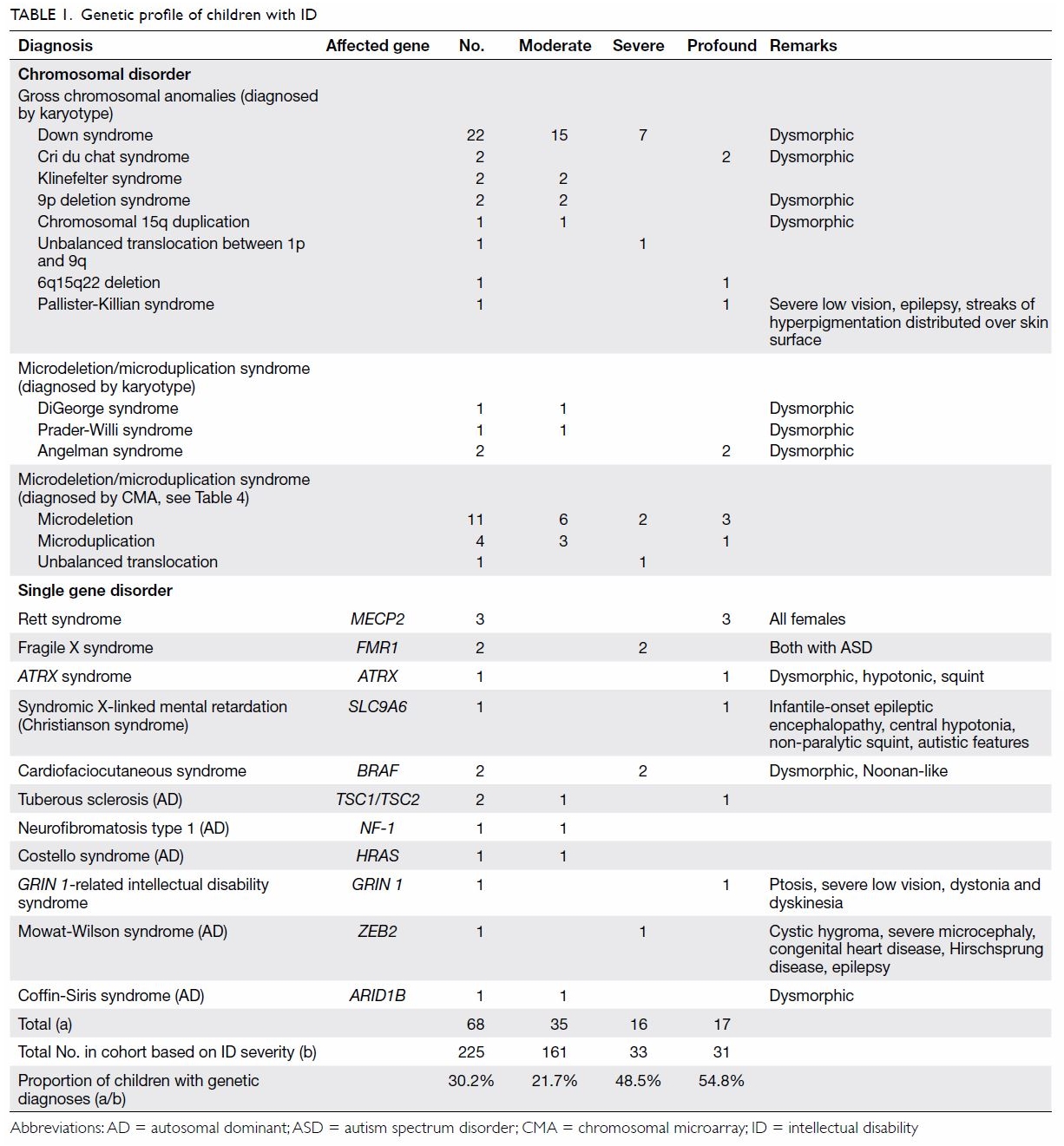

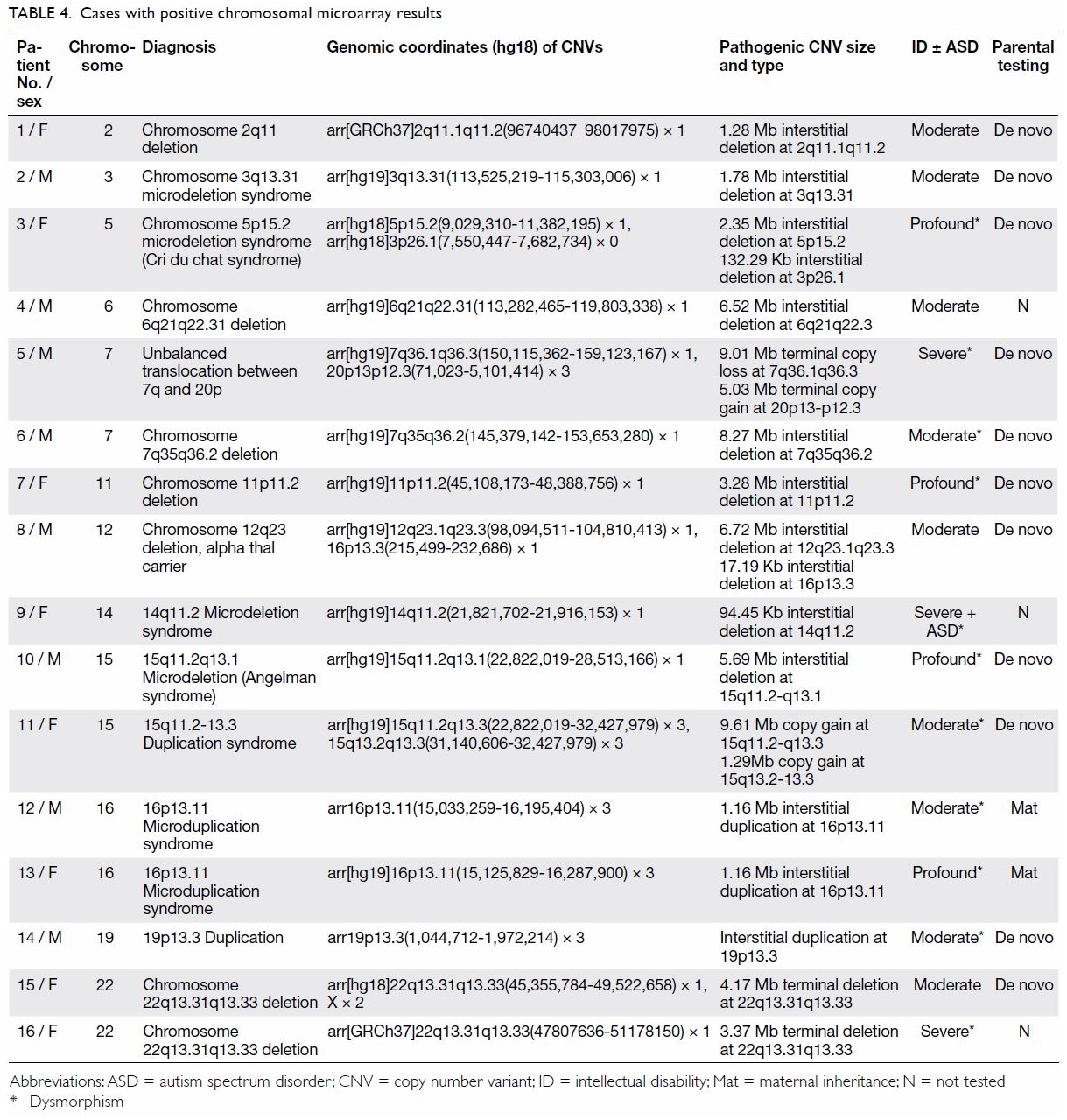

Among the 1119 valid questionnaires analysed, 767

(68.5%) were found to have mild to severe depressive symptoms (Table

2).

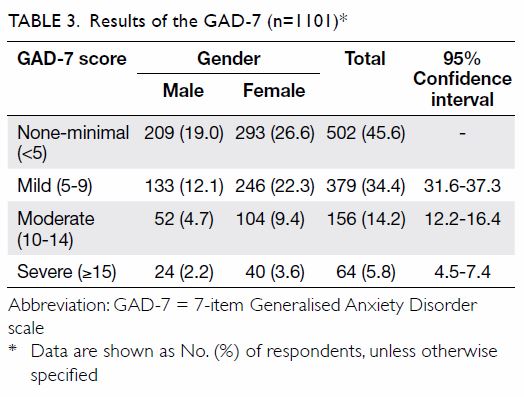

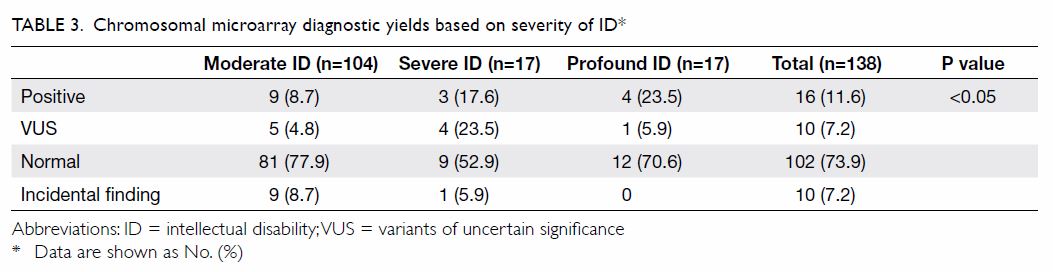

For screening of anxiety symptoms, 18 of the 1119

respondents were excluded because they did not complete the GAD-7

questionnaires; therefore, results are based on the 1101 valid responses.

A total of 599 (54.4%) respondents were found to have mild to severe

anxiety symptoms. A higher prevalence of anxiety was observed in females

than males in all three categories of severity (Table 3).

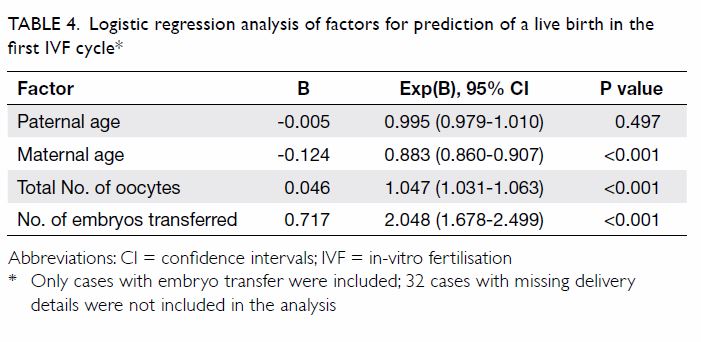

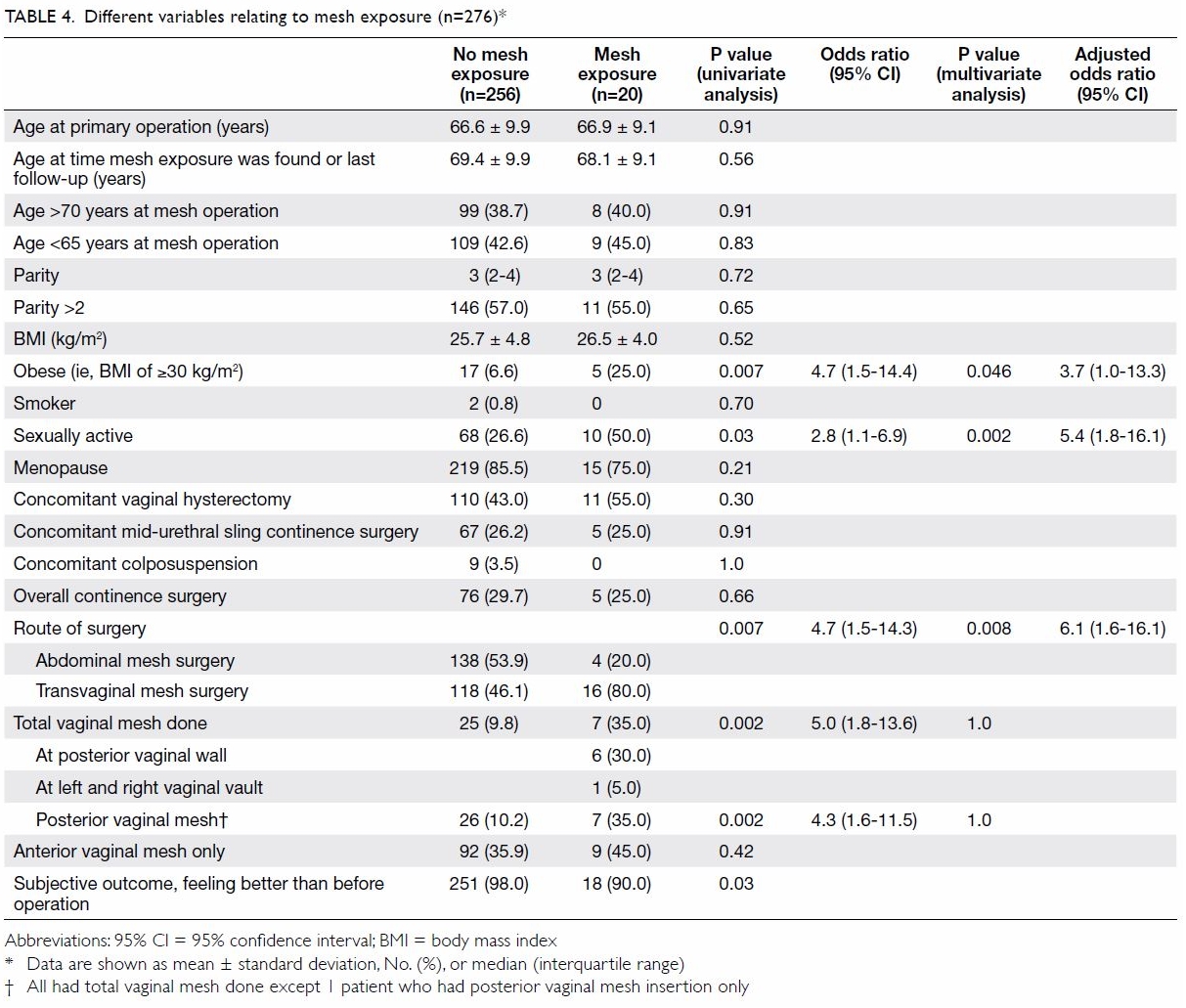

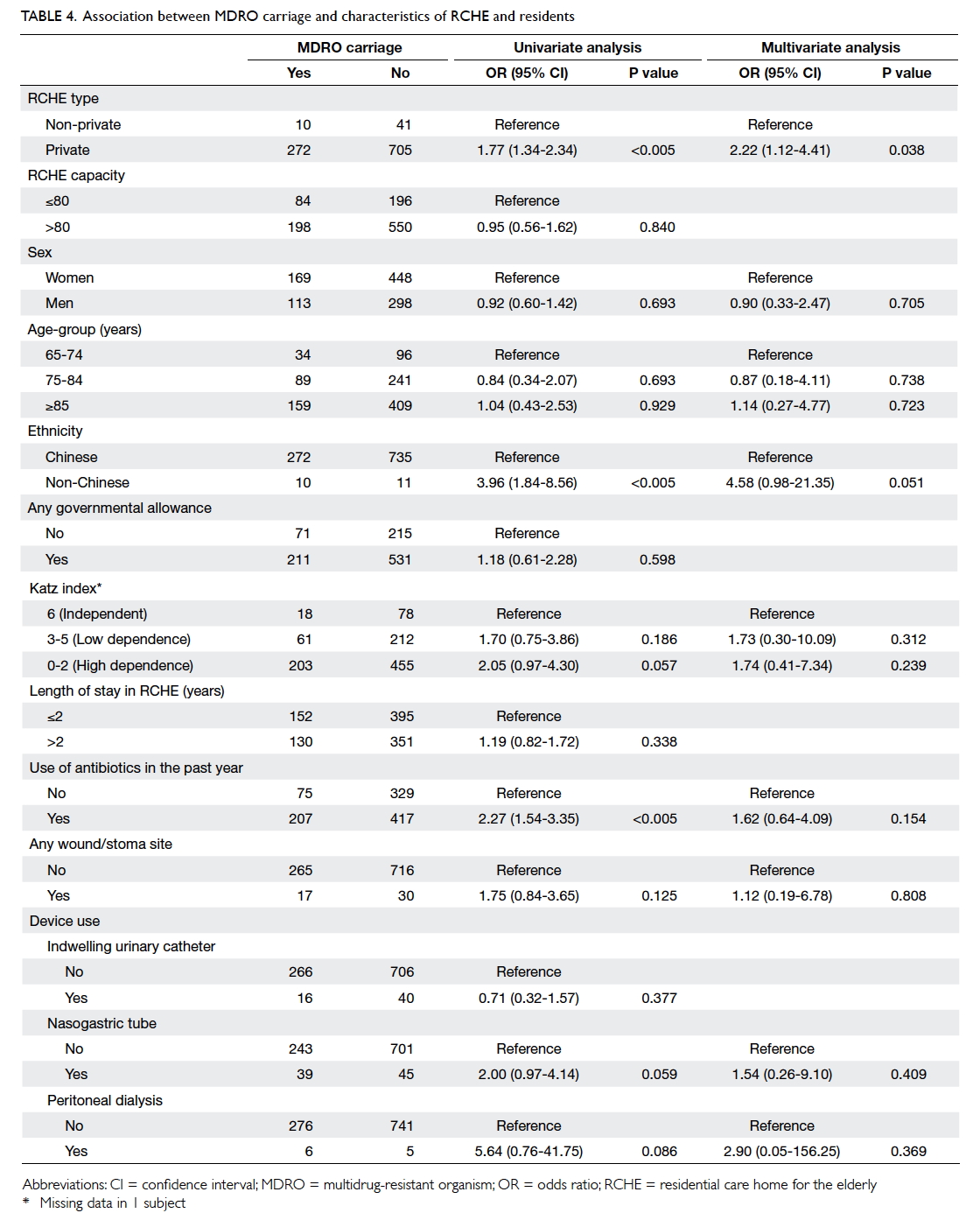

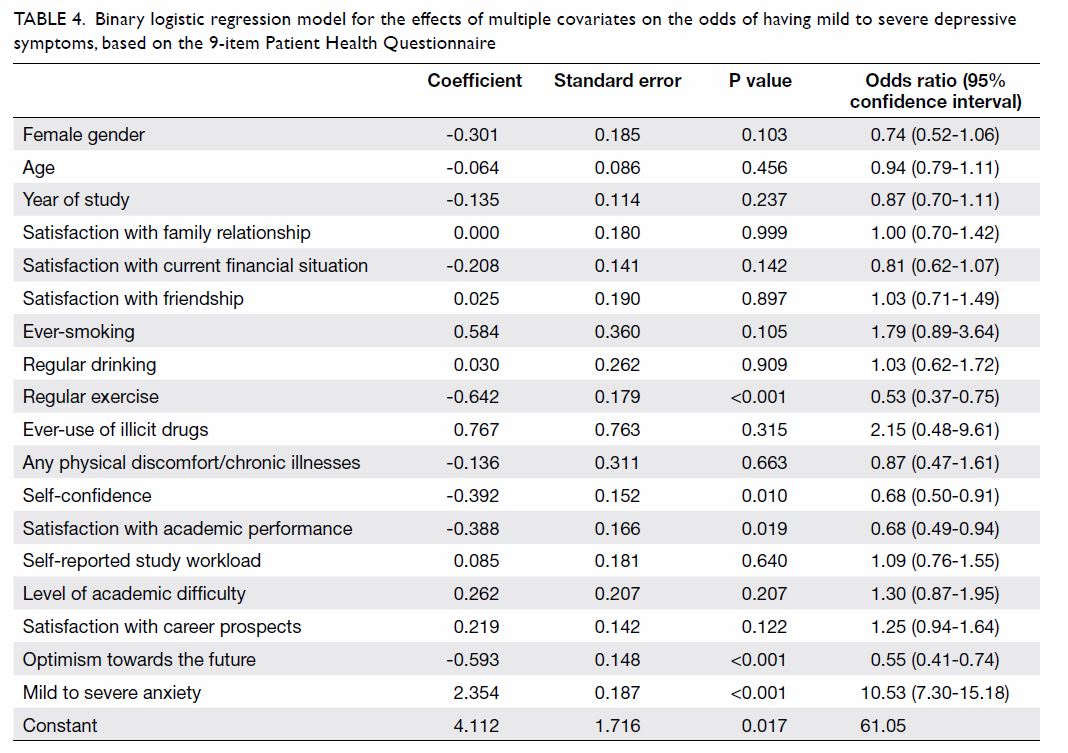

The binary logistic regression model for the

effects of multiple covariates on the odds of having mild to severe

depressive symptoms, on the basis of the PHQ-9 results, was statistically

significant with χ2=375.006, P<0.001, with 18 degrees of freedom (Table

4). The model explained 43.1% of the variance in depression

severity, as shown by Nagelkerke R2, and correctly classified

79.6% of the cases. Mild to severe anxiety symptoms, as screened by GAD-7,

were significantly associated with mild to severe depressive symptoms

(P<0.001). In contrast, several lifestyle and psychosocial variables,

including regular exercise (P<0.001), self-confidence (P=0.01),

satisfaction with academic performance (P=0.019), and optimism towards the

future (P<0.001) were inversely related to mild to severe depressive

symptoms.

Table 4. Binary logistic regression model for the effects of multiple covariates on the odds of having mild to severe depressive symptoms, based on the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire

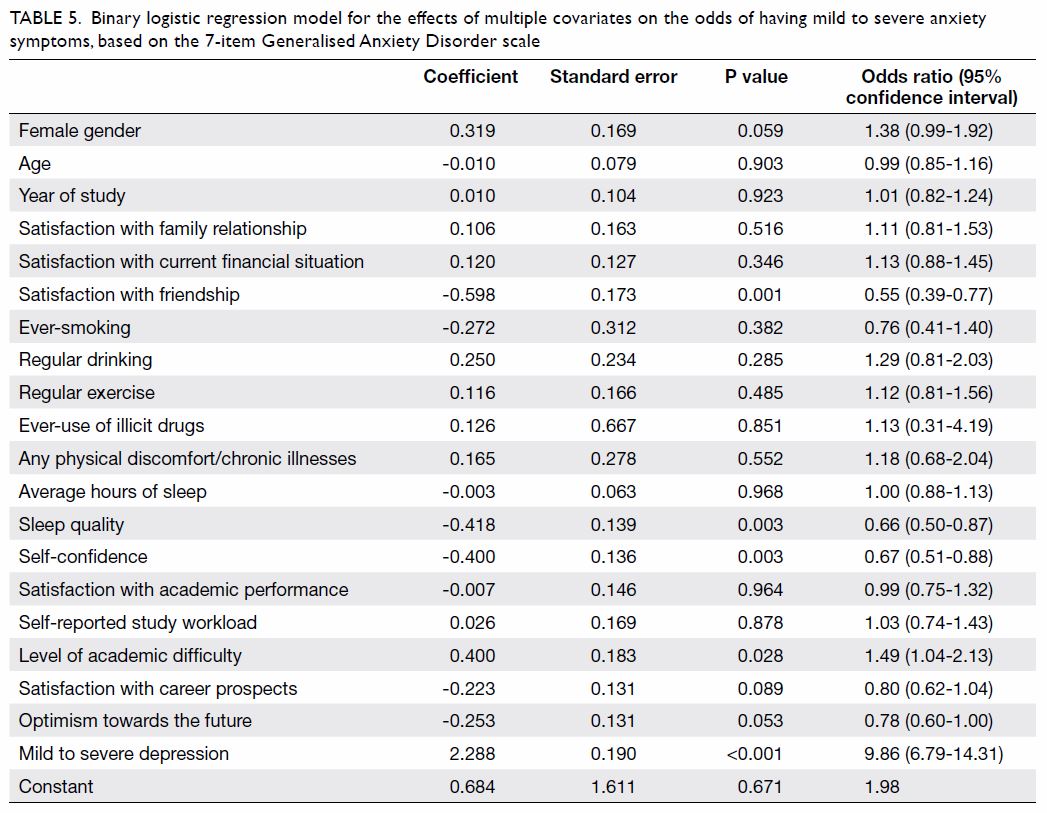

Another binary logistic regression model for the

effects of multiple covariates on the odds of having mild to severe

anxiety symptoms, on the basis of the GAD-7 results, was statistically

significant with χ2=374.842, P<0.001, with 20 degrees of

freedom (Table 5). The model explained 41.3% of the variance

in depression severity, as shown by Nagelkerke R2, and

correctly classified 76.9% of the cases. Mild to severe anxiety symptoms

were associated with level of academic difficulty (P=0.028) and mild to

severe depressive symptoms, as screened by PHQ-9 (P<0.001). Certain

lifestyle and psychosocial variables, including satisfaction with

friendship (P=0.001), sleep quality (P=0.003), and self-confidence

(P=0.003) were inversely associated with mild to severe anxiety symptoms.

Table 5. Binary logistic regression model for the effects of multiple covariates on the odds of having mild to severe anxiety symptoms, based on the 7-item Generalised Anxiety Disorder scale

Discussion

The results revealed that 68.5% of respondents had

mild to severe depressive symptoms and 54.4% had mild to severe anxiety

symptoms. These rates are higher than and comparable to the results of a

similar survey conducted by the University of Hong Kong 10 years ago,

respectively.4 This could be

attributed to the increasing academic pressure after major reforms of the

education system in Hong Kong,12

uncertainties in career prospects due to fluctuations in the

socio-political environment, and the more prevalent use of social media.13

This study revealed that mild to severe depressive

symptoms, as screened by PHQ-9, were associated with mild to severe

anxiety symptoms, as screened by GAD-7. This is consistent with previous

studies, including a study in patients with depression showing that 85% of

those with major depression were also diagnosed with generalised anxiety.14 Sharing common risk factors and

symptoms may explain their co-existence.15

16 Another study has shown that

anxiety is more frequently an antecedent of depression, but the reverse

relationship was not observed.17

This could be explained by the withdrawal and submissive techniques

adopted by individuals with anxiety, in response to social exclusion.18 However, a definite causal relationship remains

unclear.

Regular exercise could decrease the occurrence of

depression via both physiological and psychological mechanisms. Exercise

exerts an excitatory effect on the monoamine and endorphin

neurotransmitter systems; notably, monoamines are depleted in patients

with depression.19

Psychologically, exercise is reported to improve self-esteem and

self-perception through self-actualisation and gaining pleasure from an

expanded social circle.20

Psychosocial factors, including higher

self-confidence, satisfaction with academic performance, and optimism

towards the future are inversely related to depressive symptoms. These

could be the presentation or consequences of depression; these factors may

have protective effects against developing depression.21 Optimism towards the future, apart from personal

factors, is also related to community factors. Risk factors include

community disadvantage, safety, and discrimination; an important

protective factor is community connectedness. These factors were

associated with depressive symptoms.22

This implies that, in addition to promoting personal mental health,

community-level risk and protective factors that affect individuals’

optimism towards future are sufficiently important to receive broader

attention.

For the analysis of anxiety, the level of academic

difficulty was associated with mild to severe anxiety symptoms. A higher

level of academic difficulty may create greater stress and anxiety for

students; subsequent unsatisfactory academic results may complete the

vicious cycle. Several tips were suggested by the Anxiety and Depression

Association of America (ADAA) regarding test anxiety reduction.23 Female gender was not associated with mild to severe

anxiety symptoms, which conflicts with previous studies.15 No clear causality was identified, but some potential

aetiologies include higher stress levels from academic and interpersonal

issues.

Satisfaction with friendship, sleep quality, and

self-confidence were three factors inversely associated with mild to

severe anxiety symptoms. Having good interpersonal relationships with

peers could be a protective factor against anxiety; however, symptoms of

anxiety may also hinder friendship, thus explaining the inverse

relationship. Insomnia is a symptom of anxiety. According to a survey

conducted by ADAA, worrying about falling asleep at night was identified

as a cause for an increased level of anxiety.24

Recommendations that could help in falling asleep and achieving better

sleep quality include maintaining 7 to 9 hours of uninterrupted sleep,

establishing a regular bedtime routine, and avoiding electronic gadgets,

coffee, and tea, as well as designing a relaxing environment for sleeping.24 Lack of self-confidence could be

a cause of anxiety, but anxiety symptoms could also diminish one’s

self-confidence. A bilateral association is possible.

There were several limitations in our study.

Firstly, as with all cross-sectional studies, it was not possible to

establish causality between the identified factors and symptoms of

depression and anxiety. Hence, the identified factors are regarded as

associated factors, which could be either the causes or the results of

depression or anxiety. To further explore the relationships between these

factors and symptoms of depression and anxiety, we reviewed the available

literature to provide supporting evidence. Secondly, convenience sampling

was adopted, but there could be self-selection bias when inviting students

to complete the questionnaires, limited by the locations and times at

which questionnaire distribution was conducted. The questionnaires were

distributed in the open areas of the eight UGC-funded universities in Hong

Kong. Withdrawn university students affected by depression or anxiety

might not have been reached or might have refused to participate in the

study; hence, the results may be underestimates. Thirdly, we could not

attain our target number of 150 students from each university, except from

the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Importantly, this study used

screening questionnaires to assess the depressive and anxiety symptoms

experienced by the students, but no clinical diagnoses were made by health

care professionals. However, with limited resources, the use of validated

screening questionnaires was considered a cost-effective approach to

explore the situation in general and thus was used in this study. Possible

directions for further studies include the implementation of stratified

random sampling, expansion of the sample size of the study, and

performance of a reliability test to reduce information bias. Including

detailed backgrounds of students’ disciplines and faculties, as well as

ensuring a diverse population to include both local and non-local

students, as well as Chinese-speaking and non-Chinese-speaking students,

could allow further subgroup analysis; students from different faculties

may experience depressive symptoms or anxiety symptoms at different

severities due to differences in curricula. In this research, participants

who were screened to have depressive and/or anxiety symptoms were not

notified because of the lack of identifiable personal information.

Provision of the results to participants and recommendations regarding

help-seeking information are suggested for future studies. This study

result may not fully reflect the severity of depressive and anxiety

symptoms among students, as the study method could not reach severely

depressed individuals who had socially isolated themselves.

Conclusion

This study showed that over 50% of university

students in the eight UGC-funded universities expressed some degree of

depressive symptoms (68.5%) or anxiety symptoms (54.4%). Notably, 9% of

these university students exhibited moderate to severe depressive symptoms

and 5.8% of the studied students showed severe anxiety symptoms. Students

with regular exercise, higher self-confidence, better satisfaction with

academic performance, and more optimism towards the future experienced

fewer depressive symptoms. Students with better satisfaction with

friendship, better sleep quality, higher self-confidence, and lower levels

of academic difficulty experienced fewer anxiety symptoms.

Author contributions

Concept or design of study: KWC Lun, CK Chan.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the article: All authors.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: KWC Lun, CK Chan.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the article: All authors.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: KWC Lun, CK Chan.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr LM Ho, assistant IT director of the

Division of Epidemiology and Biostatistics of School of Public Health of

the University of Hong Kong, for his statistical support and advice in

conducting this study. We also thank the School of Public Health of the

University of Hong Kong, for its support in conducting this study.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of

interest. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility

for its accuracy and integrity.

Funding/support

The LKS Faculty of Medicine, University of Hong

Kong reimbursed project expenses under the title of Health Research

Project for HKD500.

Ethical approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the

Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital

Authority Hong Kong West Cluster.

References

1. Hong Kong Jockey Club Centre for Suicide

Research and Prevention, The University of Hong Kong. Statistics.

Available from: https://csrp.hku.hk/statistics/. Accessed 18 Sep 2018.

2. Centre for Health Protection, Department

of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Depression: beyond feeling blue.

Non-Communicable Diseases Watch 2012. Available from:

https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/ncd_watch_sep2012.pdf. Accessed 20 Apr

2016.

3. Centre for Health Protection, Department

of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Population Health Survey 2003/2004.

Collaborative project of Department of Health and Department of Community

Medicine, University of Hong Kong, Available from:

https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/report_on_population_health_survey_2003_2004_en.pdf.

Accessed 20 Apr 2016.

4. Wong JG, Cheung EP, Chan KK, Ma KK, Tang

SW. Web-based survey of depression, anxiety and stress in first-year

tertiary education students in Hong Kong. Aust N Z J Psychiatry

2006;40:777-82. Crossref

5. Lam LC, Wong CS, Wang MJ, et al.

Prevalence, psychosocial correlates and service utilization of depressive

and anxiety disorders in Hong Kong: the Hong Kong Mental Morbidity Survey

(HKMMS). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2015;50:1379-88. Crossref

6. Cairns KE, Yap MB, Pilkington PD, Jorm

AF. Risk and protective factors for depression that adolescents can

modify: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J

Affect Disord 2014;169:61-75. Crossref

7. Yu X, Tam WW, Wong PT, Lam TH, Stewart

SM. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for measuring depressive symptoms

among the general population in Hong Kong. Compr Psychiatry

2012;53:95-102. Crossref

8. Wang W, Bian Q, Zhao Y, et al.

Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Patient Health

Questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry

2014;36:539-44. Crossref

9. Martin A, Rief W, Klaiberg A, Braehler

E. Validity of the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire Mood Scale (PHQ-9)

in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2006;28:71-7. Crossref

10. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB,

Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the

GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092-7. Crossref

11. Tong X, An D, McGonigal A, Park SP,

Zhou D. Validation of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) among

Chinese people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 2016;120:31-6. Crossref

12. Yeh YC, Yen CF, Lai CS, Huang CH, Liu

KM, Huang IT. Correlations between academic achievement and anxiety and

depression in medical students experiencing integrated curriculum reform.

Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2007;23:379-86. Crossref

13. O’Keeffe GS, Clarke-Pearson K, Council

on Communications and Media. The impact of social media on children,

adolescents, and families. Pediatrics 2011;127:800-4. Crossref

14. Hall RC, Platt DE, Hall RC. Suicide

risk assessment: a review of risk factors for suicide in 100 patients who

made severe suicide attempts. Evaluation of suicide risk in a time of

managed care. Psychosomatics 1999;40:18-27. Crossref

15. Blanco C, Rubio J, Wall M, Wang S, Jiu

CJ, Kendler KS. Risk factors for anxiety disorders: common and specific

effects in a national sample. Depress Anxiety 2014;31:756-64. Crossref

16. van Ameringen M. Comorbid anxiety and

depression in adults: Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and

diagnosis. 15 Jun 2017. Available from:

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/comorbid-anxiety-and-depression-in-adults-epidemiology-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis.

Accessed 24 Jul 2017.

17. Muris P. Normal and Abnormal Fear and

Anxiety in Children and Adolescents. London: Elsevier; 2007.

18. Richards CS, O’Hara MW, editors. The

Oxford Handbook of Depression and Comorbidity. New York: Oxford University

Press; 2014.Crossref

19. Buckworth J, Dishman RK. Exercise

Psychology. Champaign: Human Kinetics; 2002.

20. Faulkner GE, Taylor AH, editors.

Exercise, Health and Mental Health: Emerging Relationships. New York:

Routledge; 2005. Crossref

21. Wang KT. Perfectionism, depression,

and self-esteem: a comparison of Asian and Caucasian Americans from a

collectivistic perspective [dissertation]. Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania

State University; 2007.

22. Stirling K, Toumbourou JW, Rowland B.

Community factors influencing child and adolescent depression: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2015;49:869-86.

Crossref

23. Anxiety and Depression Association of

America. Test Anxiety. Available from:

https://www.adaa.org/living-with-anxiety/children/test-anxiety. Accessed

23 Mar 2017.

24. Anxiety and Depression Association of

America. Stress and Anxiety Interferes with sleep. Available from:

https://www.adaa.org/understanding-anxiety/related-illnesses/other-related-conditions/stress/stress-and-anxietyinterfere.

Accessed 23 Mar 2017.