Lemierre’s syndrome: an often forgotten but potentially life-threatening disease

Hong Kong Med J 2016 Apr;22(2):184.e1–2

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154696

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PICTORIAL MEDICINE

Lemierre’s syndrome: an often forgotten but potentially life-threatening disease

C Lee, MB, BS, FRCR;

Lorraine HY Sinn, MB, BS, FRCR;

Sonia HY Lam, MB, BS, FRCR;

WM Lam, MB, BS, FRCR

Department of Radiology, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr C Lee (leechunbruce@gmail.com)

An earlier version of this paper was presented as a poster at the European

Society of Thoracic Radiology held in Barcelona, Spain on 4-6 June 2015.

A 20-year-old Chinese female with good past health

presented to the emergency department in October

2014 with a few days history of fever, dizziness, and

headache. She was hypotensive upon presentation

with blood pressure of 73/48 mm Hg and pulse rate

of 90 beats/min but responded to fluid resuscitation.

Physical examination revealed no other significant

findings. Her white cell count was 4.4 x 109 /L on

admission but increased to 13.4 x 109 five days later.

Neutrophil predominance was observed. Subsequent

gradual decline and normalisation of the white cell

count was noted after initiation of intravenous

antibiotics.

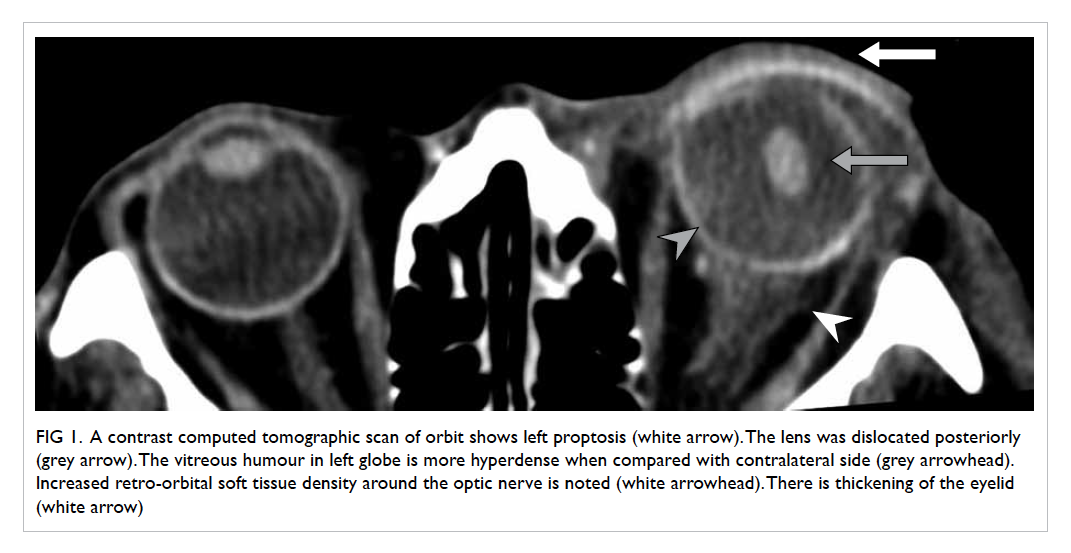

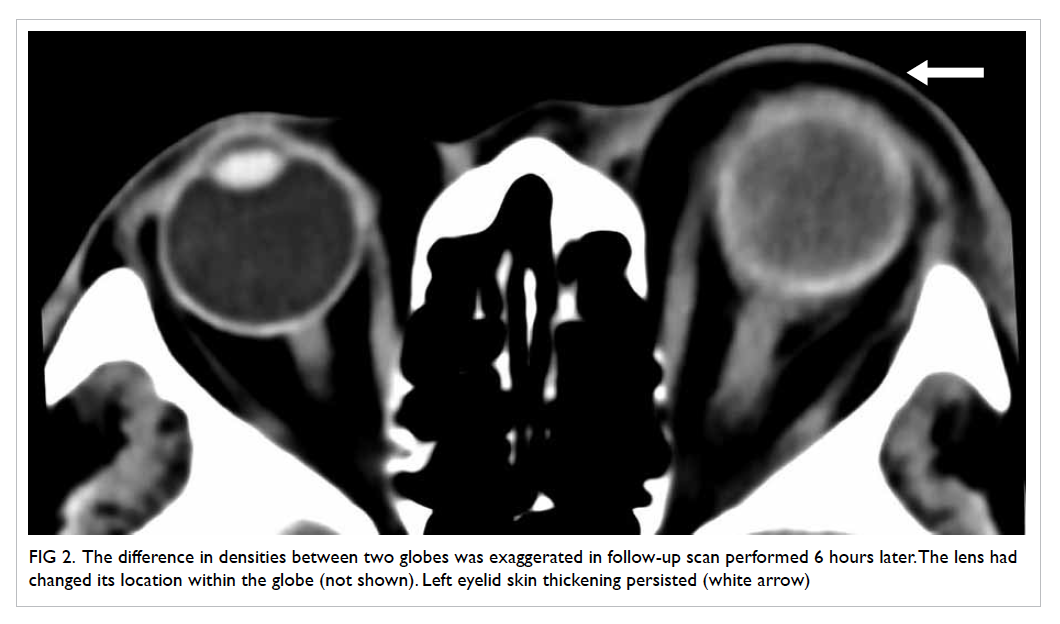

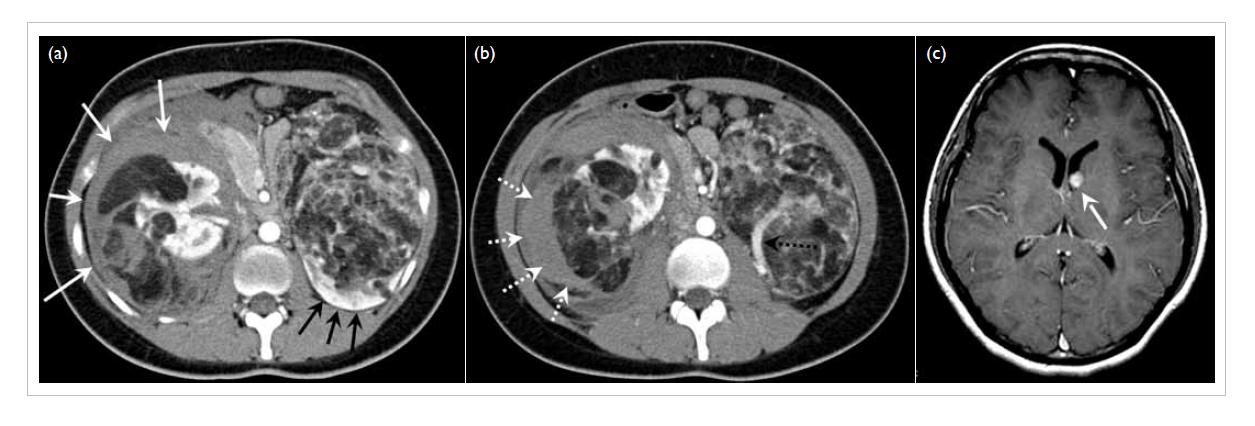

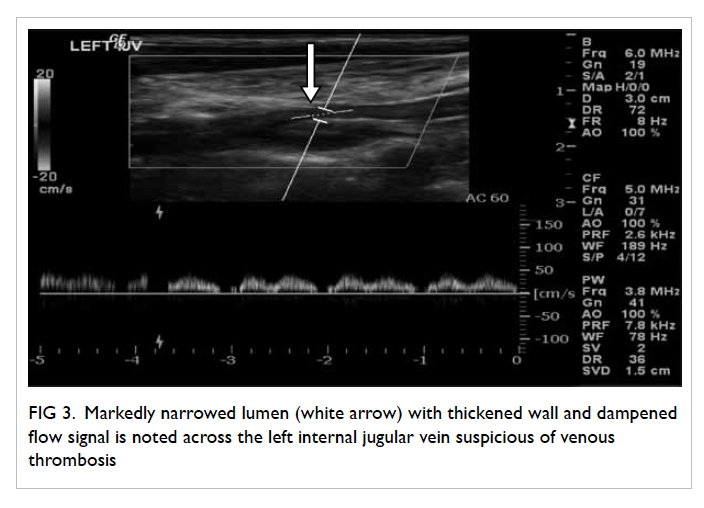

Computed tomographic (CT) abdomen and

pelvis was initially requested based on the clinical

suspicion of intra-abdominal sepsis or gynaecological

pathologies but yielded no remarkable findings. Chest

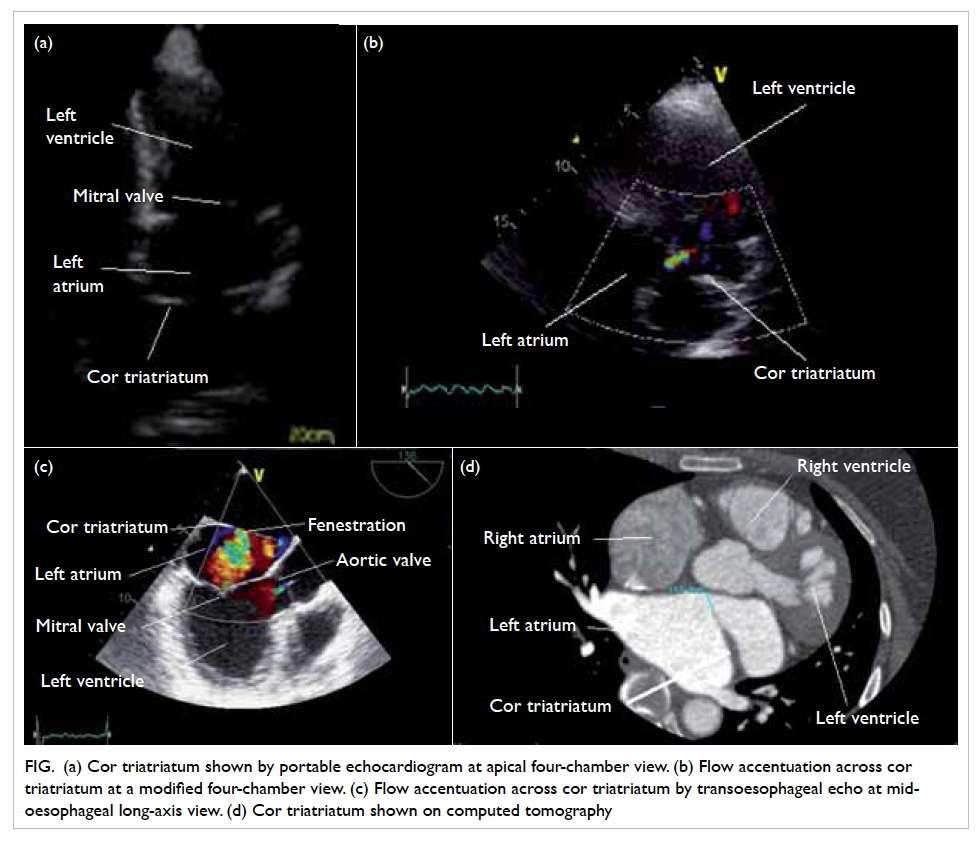

X-ray (CXR) was also performed for preliminary

assessment and was initially unremarkable. Follow-up

serial CXRs, however, showed an increasing

number of cavitary lesions in both lungs with no

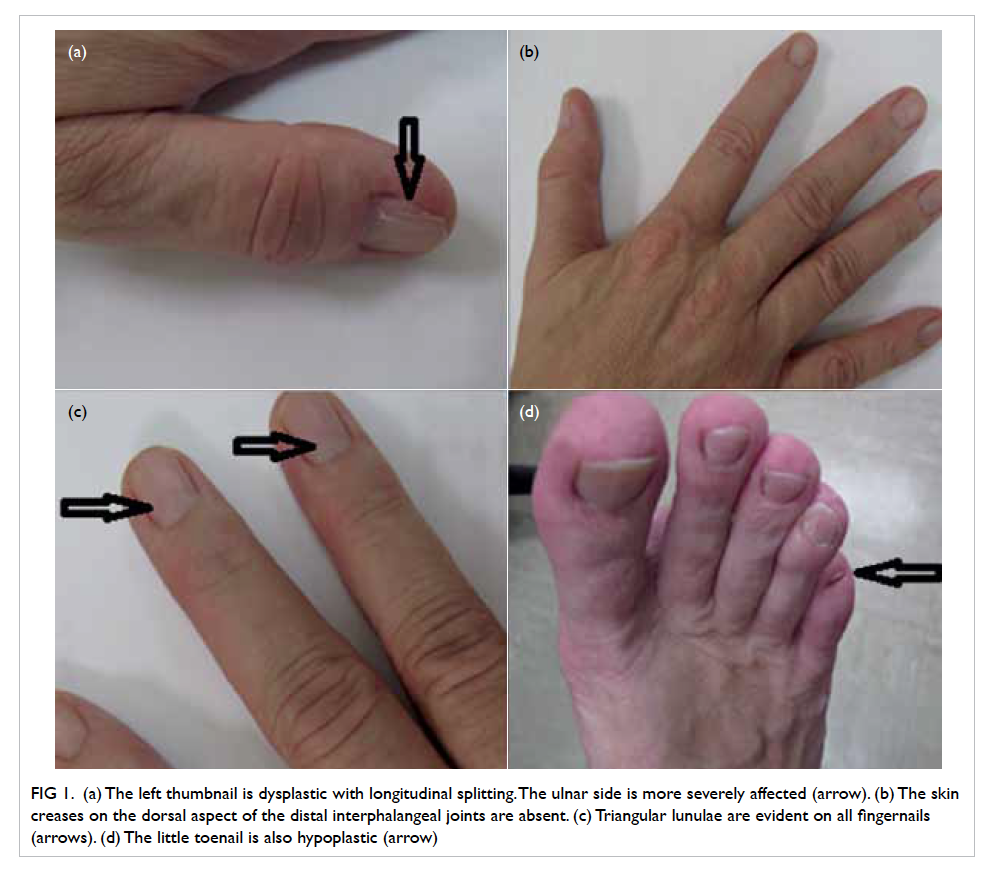

zonal predominance (Fig 1).

Figure 1. Chest X-ray revealing multiple cavitary lesions of variable size in the bilateral lung fields with no zonal predominance (black arrows)

Area of consolidation is also evident in the right lower zone (white arrow)

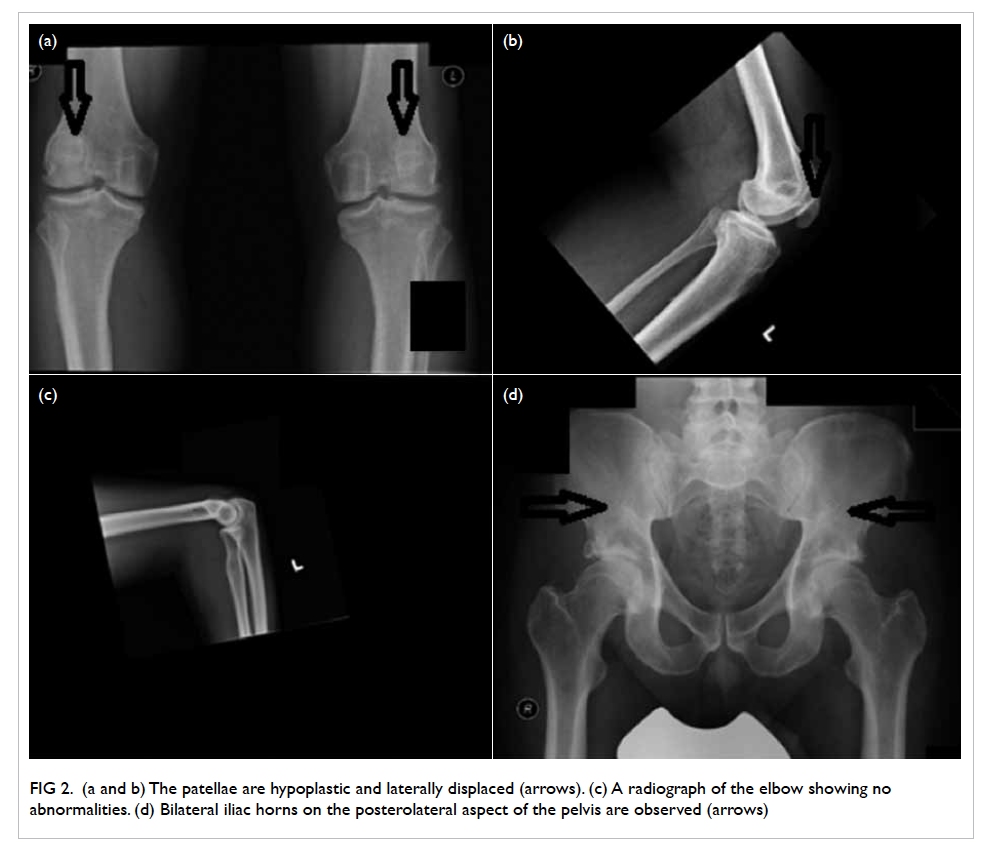

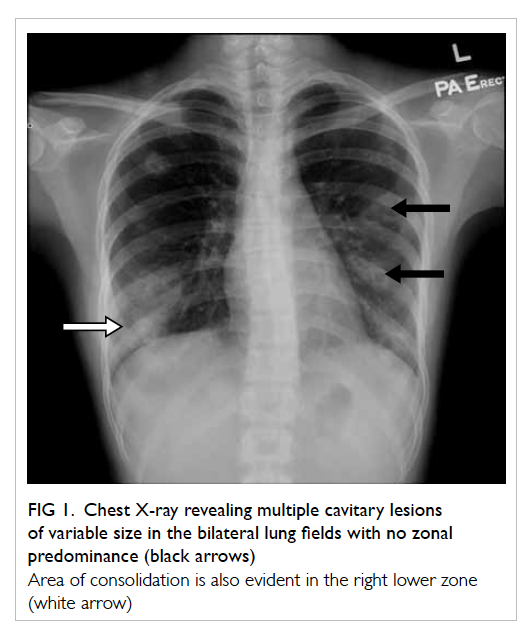

Non-contrast CT thorax was deemed necessary

for further characterisation of these lesions and

confirmed multiple cavitary lesions of variable sizes

involving all the lung lobes (Fig 2). Thick irregular

walls with fluid content and perifocal consolidative

changes were noted in some of these lesions, which are

compatible with an infective process. Further imaging

workup was then arranged to identify any potential

source of the septic emboli but echocardiogram did

not reveal any heart valve vegetation.

Figure 2. Computed tomographic thorax demonstrating multiple cavitary lesions of variable size involving all the lung lobes

The right lower zone lesion shows perifocal consolidative changes (white arrow) in some of these lesions, compatible with an infective process

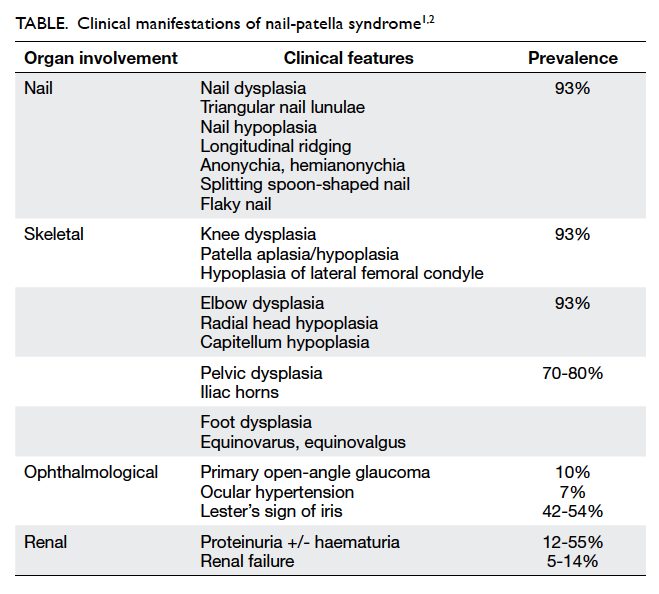

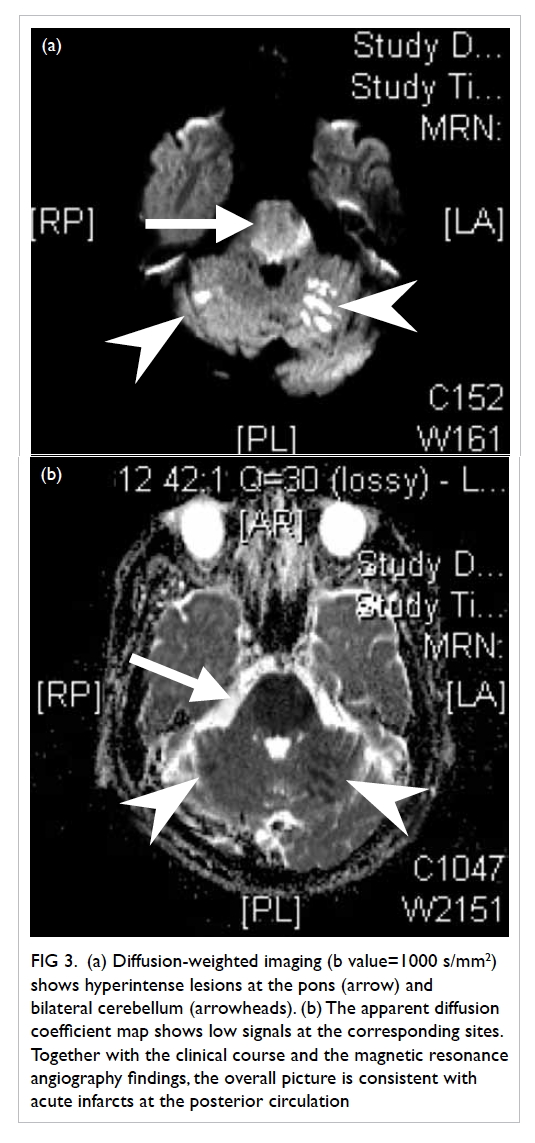

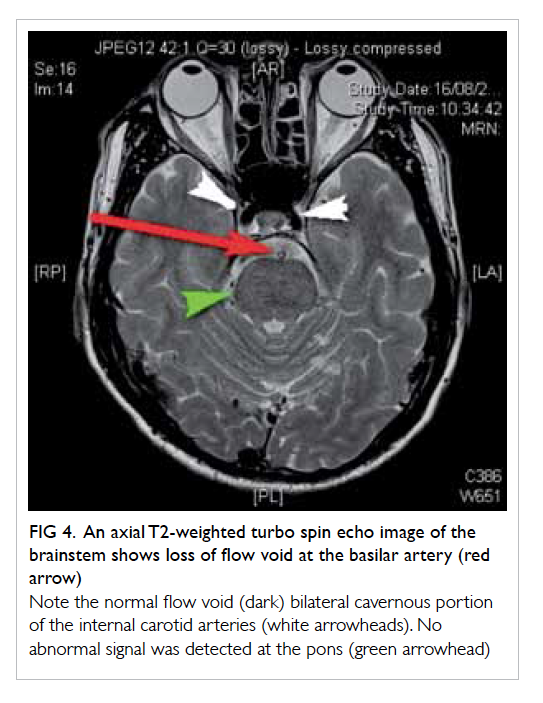

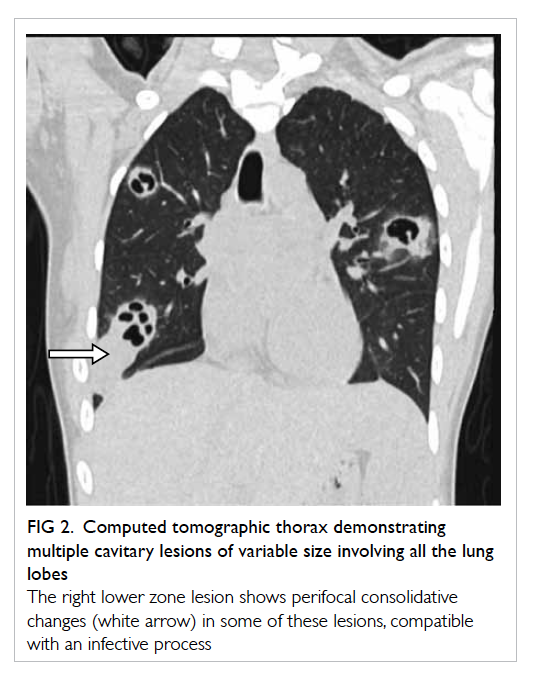

On further questioning, the patient reported

mild left neck pain. Doppler ultrasound of the neck

was then performed based on the clinical suspicion

of Lemierre’s syndrome. A markedly narrowed lumen

with thickened wall and dampened flow signal was

noted across the left internal jugular vein suspicious

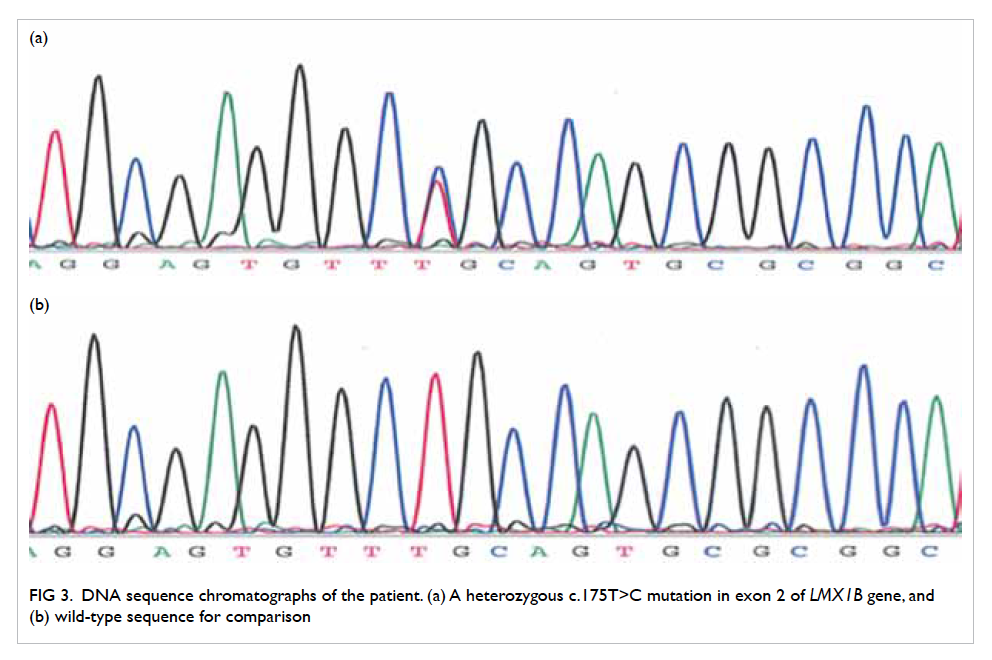

of venous thrombosis (Fig 3). This was subsequently

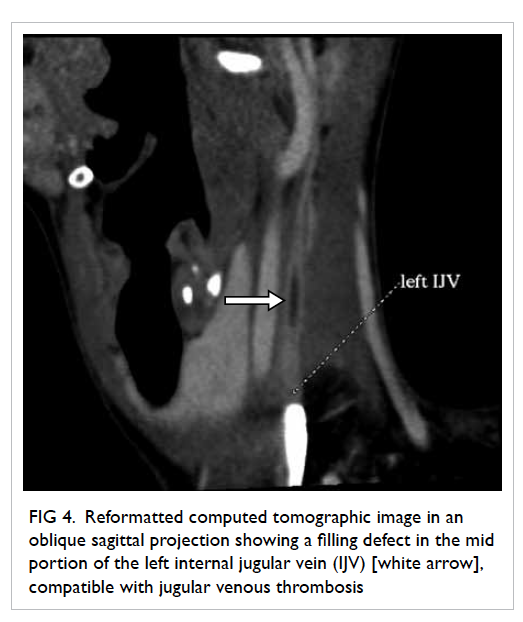

confirmed on contrast CT neck and thorax (Fig 4).

Figure 3. Markedly narrowed lumen (white arrow) with thickened wall and dampened flow signal is noted across the left internal jugular vein suspicious of venous thrombosis

Figure 4. Reformatted computed tomographic image in an oblique sagittal projection showing a filling defect in the mid portion of the left internal jugular vein (IJV) [white arrow], compatible with jugular venous thrombosis

Mycoplasma-Fusobacterium polymerase chain

reaction study confirmed the causative organism as

Fusobacterium necrophorum, which is the classic

bacteria described in Lemierre’s syndrome.

The patient was promptly treated with

intravenous antibiotics and anticoagulant. Her

clinical condition gradually improved and follow-up

CT scan demonstrated interval resolution of

the cavitary lung lesions. She was subsequently

discharged with oral antibiotics and anticoagulants.

Lemierre’s syndrome remains a rare yet

potentially life-threatening disease especially in young

adults.1 A high index of clinical suspicion is therefore

imperative to ensure prompt and timely imaging

investigations that are integral to its diagnosis.

Unrecognised and untreated systemic dissemination

can result in a poor prognosis.2 Contrast-enhanced

CT played a pivotal role in terms of evaluation of the

pulmonary sepsis and assessment of the jugular vein

thrombosis in this patient.3

References

1. Shook J, Trigger C. Lemierre’s Syndrome. West J Emerg

Med 2014;15:125-6. Crossref

2. Lai C, Vummidi DR. Images in clinical medicine.

Lemierre’s Syndrome. N Engl J Med 2004;350:e14. Crossref

3. Screaton NJ, Ravenel JG, Lehner PJ, Heitzman ER, Flower

CD. Lemierre syndrome: forgotten but not extinct—report

of four cases. Radiology 1999;213:369-74. Crossref