Primary pelvic retroperitoneal ancient schwannoma—a rare diagnosis of pelvic complex cystic lesion

Hong

Kong Med J 2019 Apr;25(2):160–1.e1–3

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PICTORIAL MEDICINE

Primary pelvic retroperitoneal ancient schwannoma—a

rare diagnosis of pelvic complex cystic lesion

TS Chan, MB, BS, FRCR; T Wong, FRCR, FHKAM

(Radiology); NY Pan, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)

Department of Radiology, Princess Margaret

Hospital, Kwai Chung, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr TS Chan (drsunchan@gmail.com)

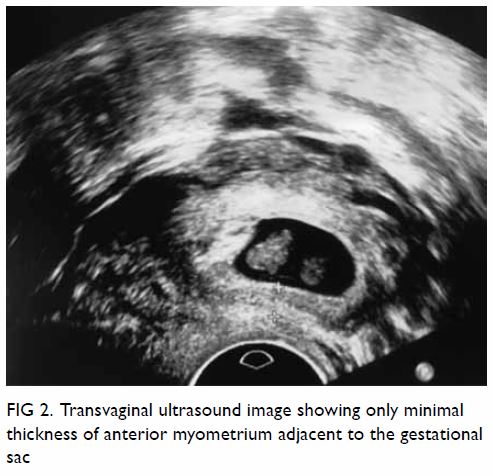

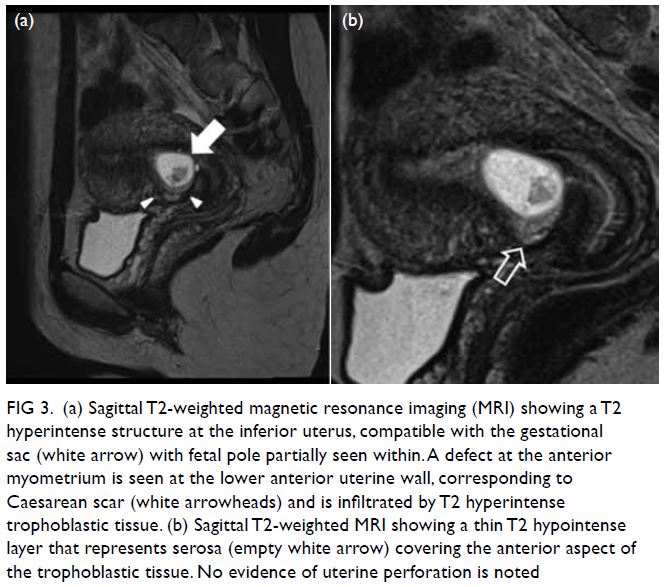

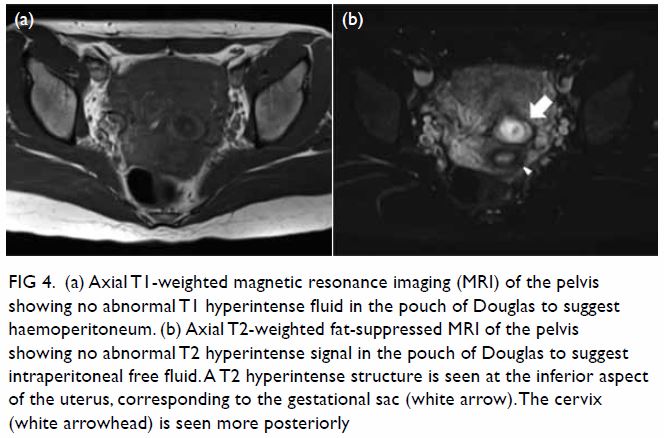

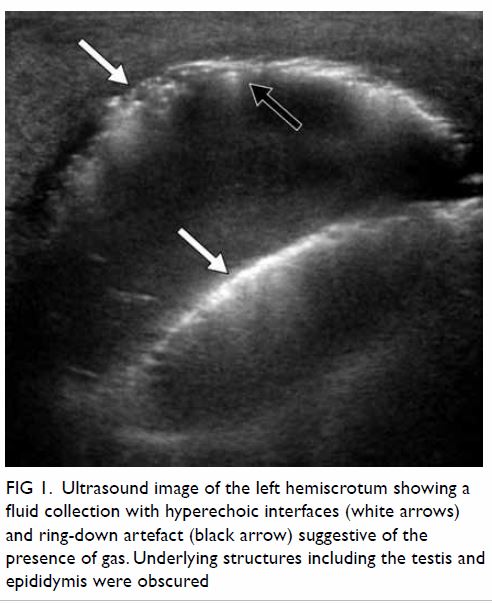

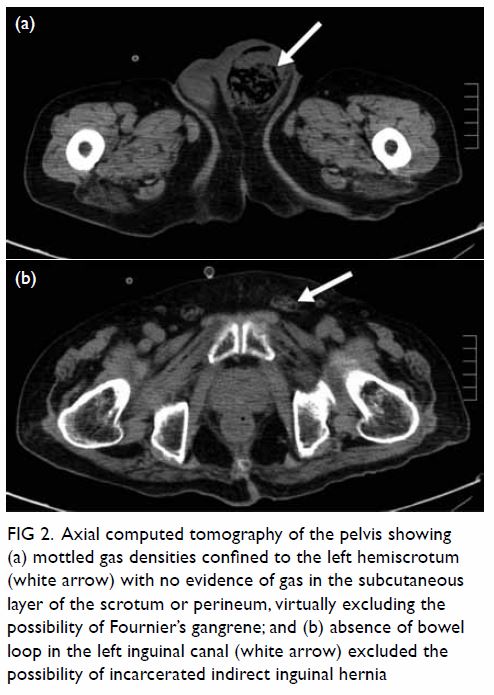

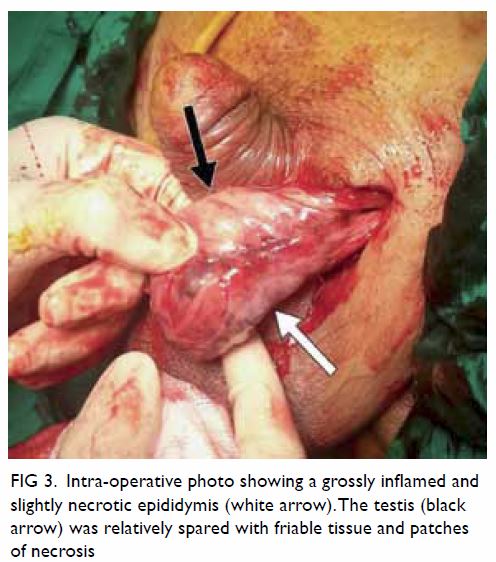

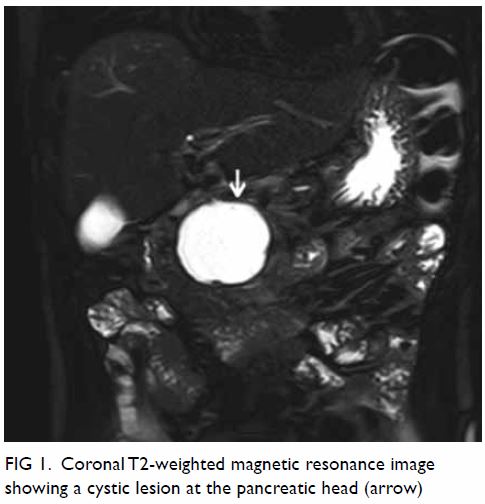

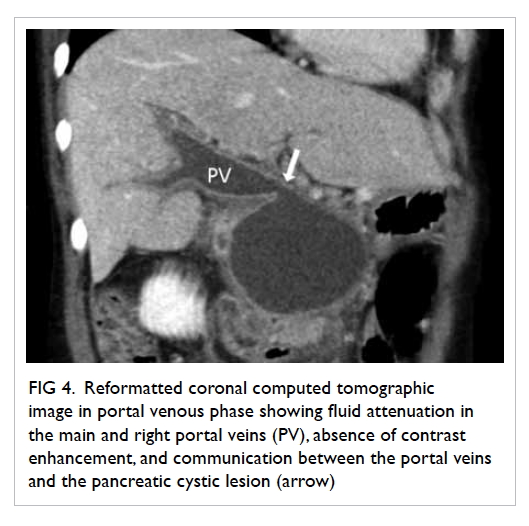

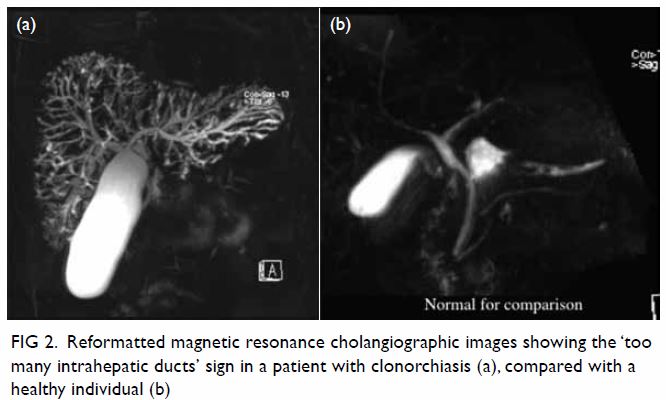

A 42-year-old woman was admitted through our

emergency department for subacute onset of lower abdominal pain in

September 2014. Bedside ultrasound by a gynaecology specialist showed a

left adnexal cyst with fluid interface. Magnetic resonance imaging of the

pelvis showed a large well-defined multiloculated cystic lesion measuring

9.2 cm (width) × 8.5 cm (depth) × 8.9 cm (height) with thick T1 and T2

hypointense enhancing wall and septa at the left side of the pelvis (Fig

1). An internal slightly T1 hyperintense component with fluid-fluid

level was suspected to be proteinaceous or haemorrhagic content. A 1.6-cm

non-enhancing mural nodule was noted at the posterior aspect. Partial

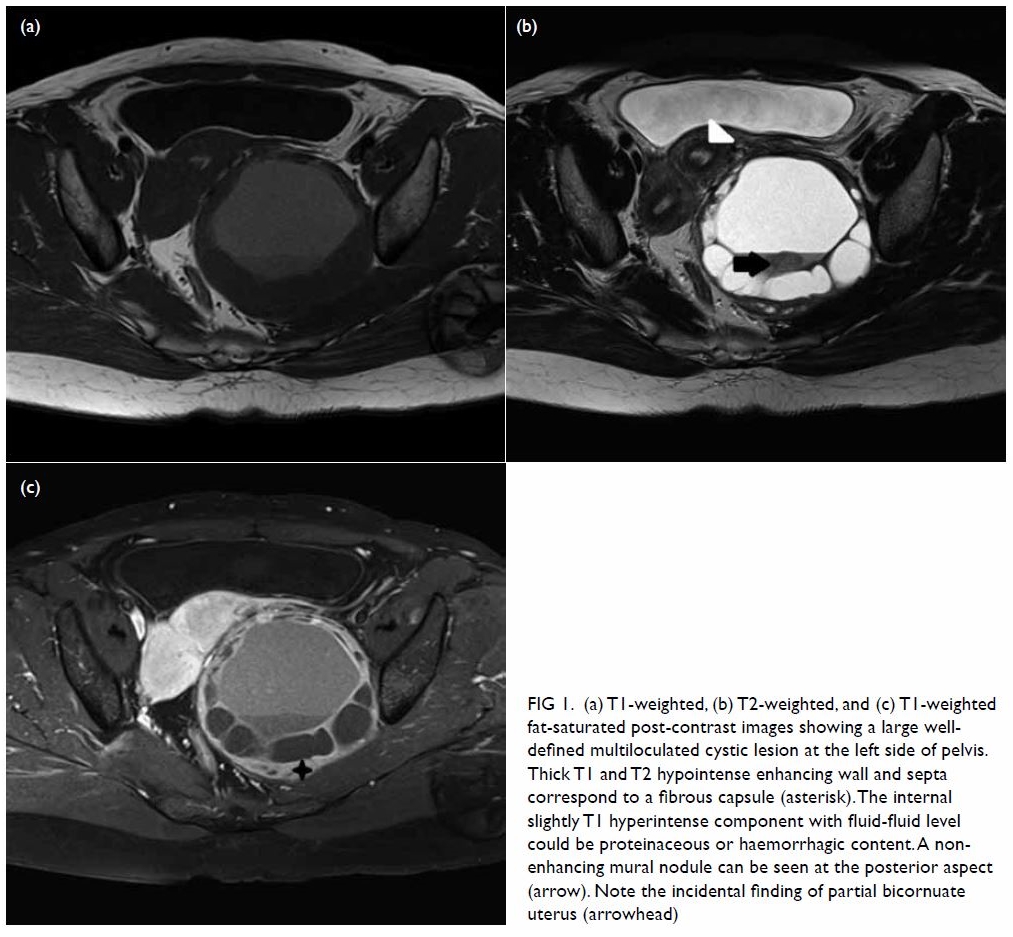

bicornuate uterus was noted. Bilateral ovaries were normal in size with

small cysts (Fig 2). Laparoscopy was done, with

excision of the lesion. Intra-operative frozen section showed a benign

spindle cell tumour. Final histopathological evaluation revealed a

retroperitoneal schwannoma.

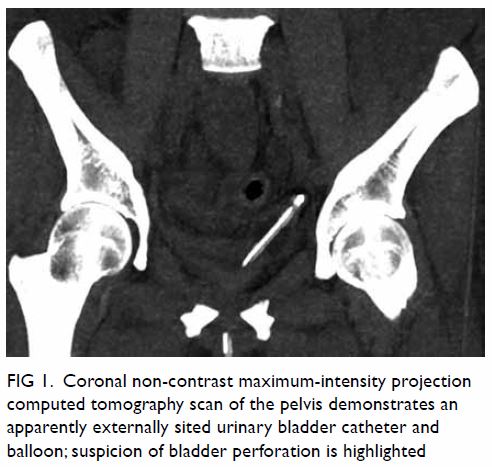

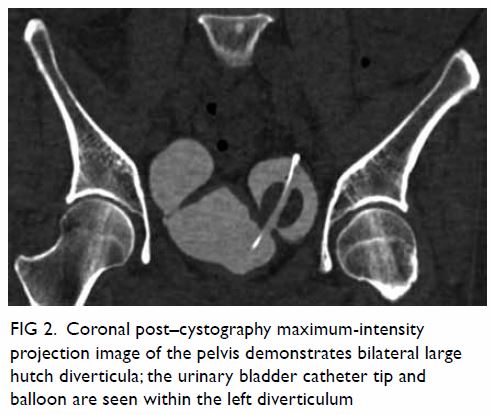

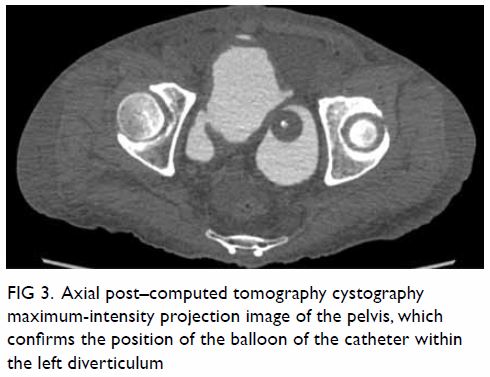

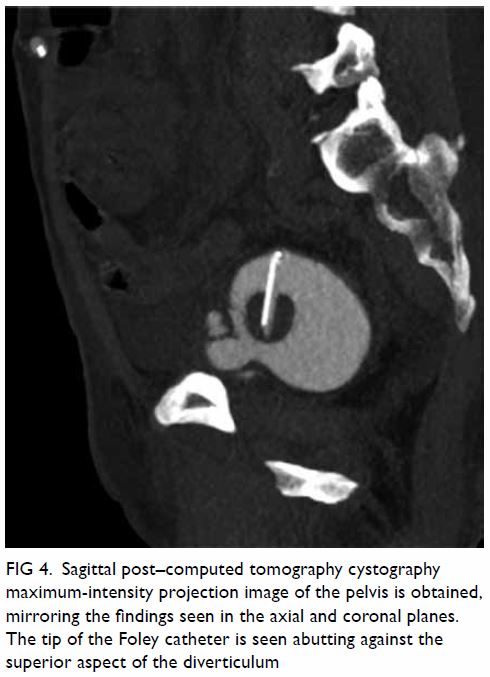

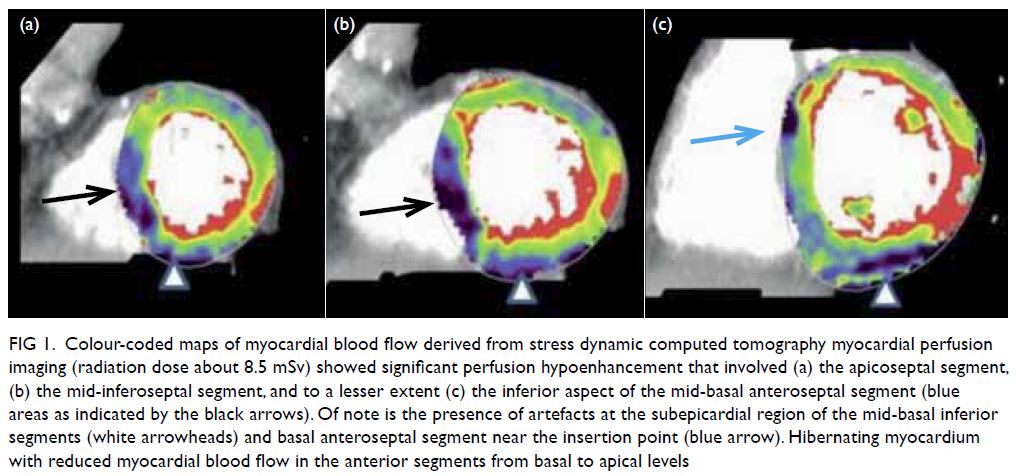

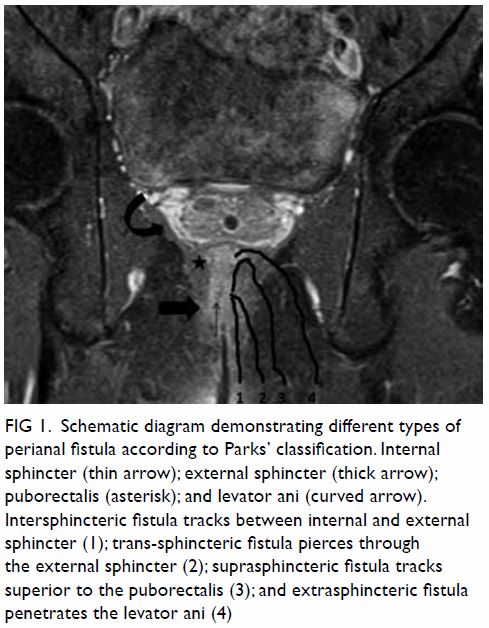

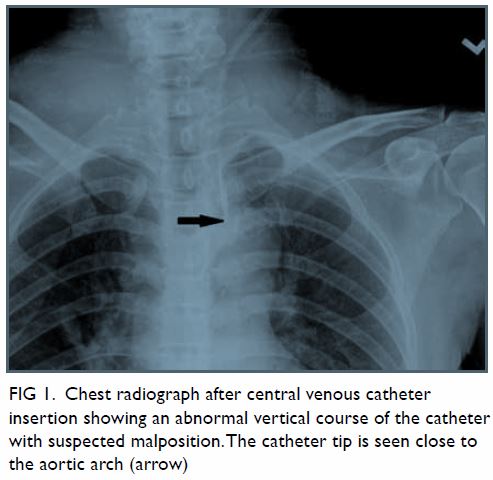

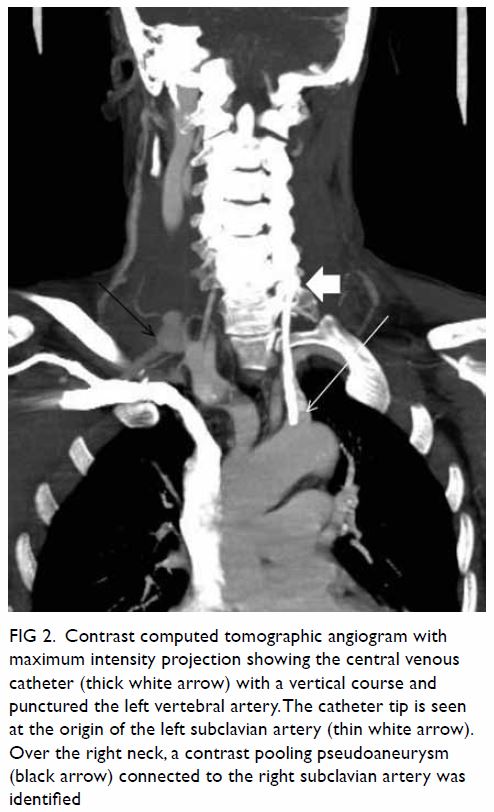

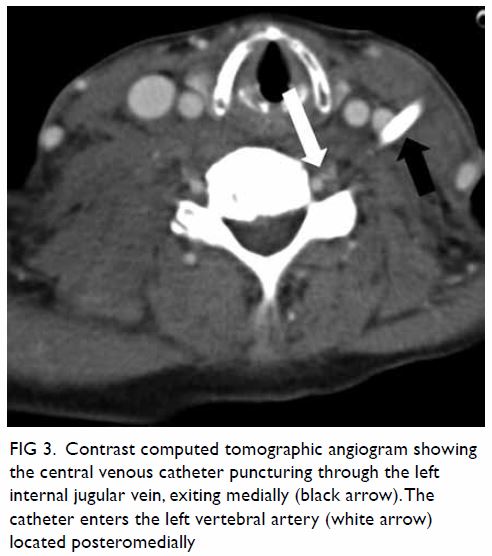

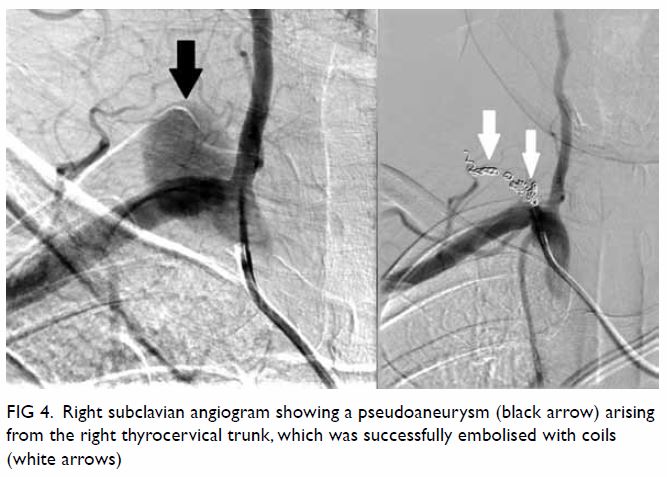

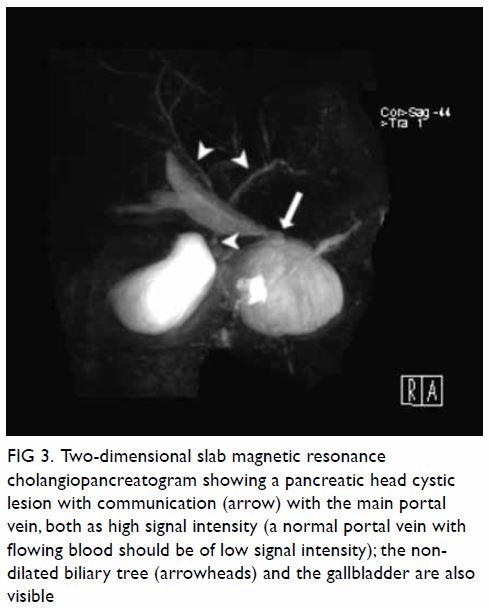

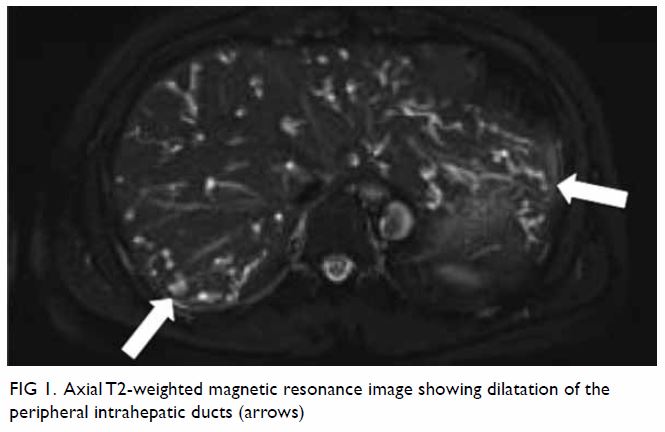

Figure 1. (a) T1-weighted, (b) T2-weighted, and (c) T1-weighted fat-saturated post-contrast images showing a large welldefined multiloculated cystic lesion at the left side of pelvis. Thick T1 and T2 hypointense enhancing wall and septa correspond to a fibrous capsule (asterisk). The internal slightly T1 hyperintense component with fluid-fluid level could be proteinaceous or haemorrhagic content. A nonenhancing mural nodule can be seen at the posterior aspect (arrow). Note the incidental finding of partial bicornuate uterus (arrowhead)

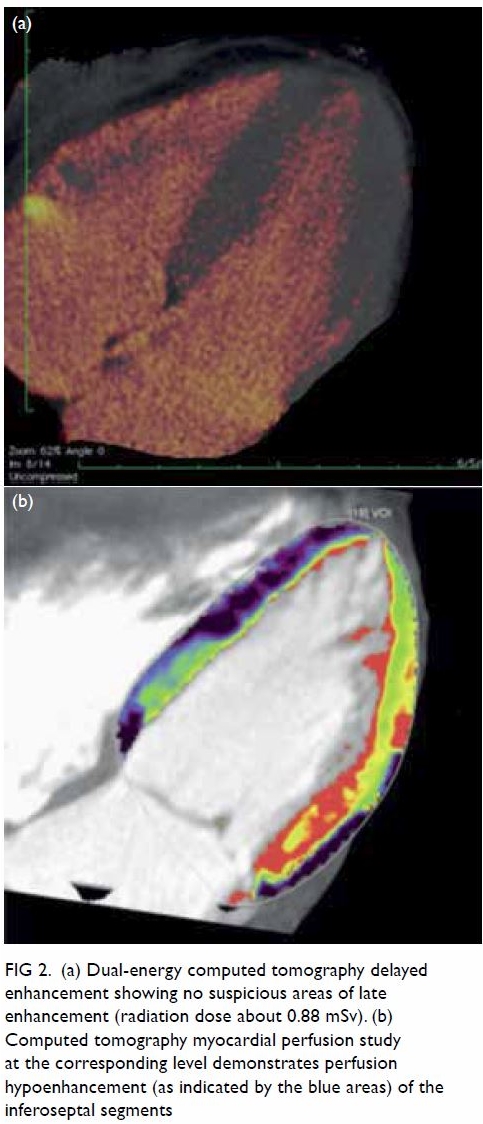

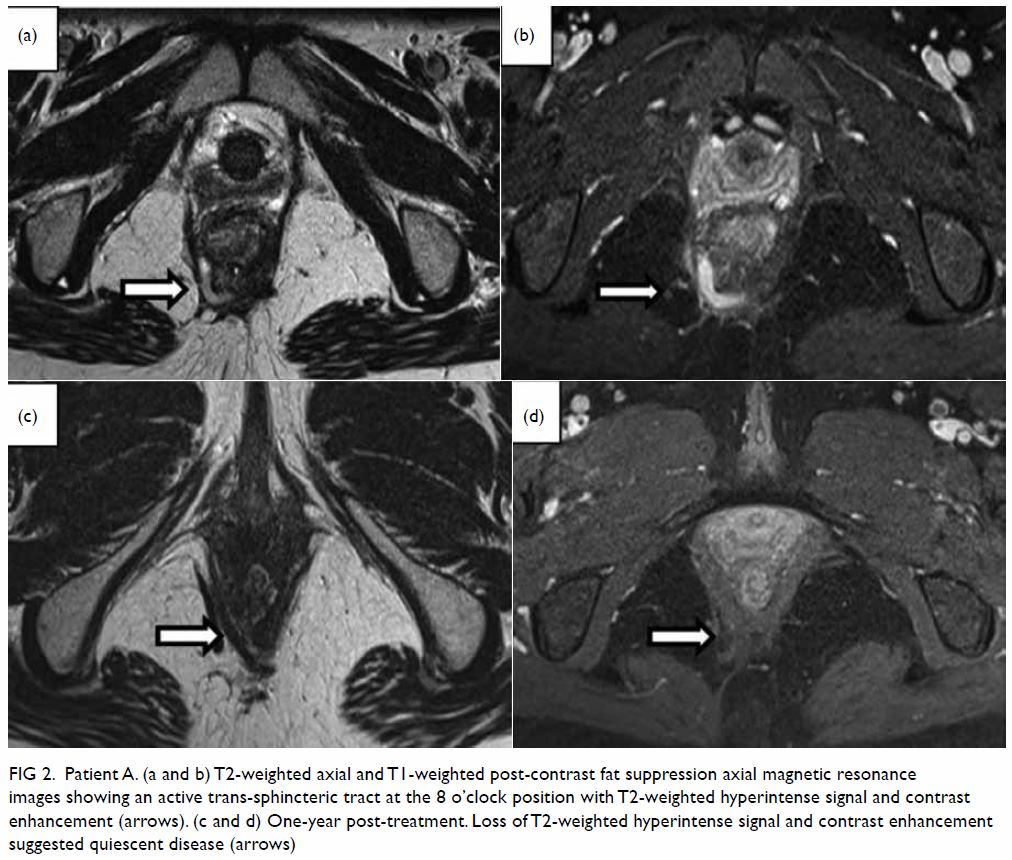

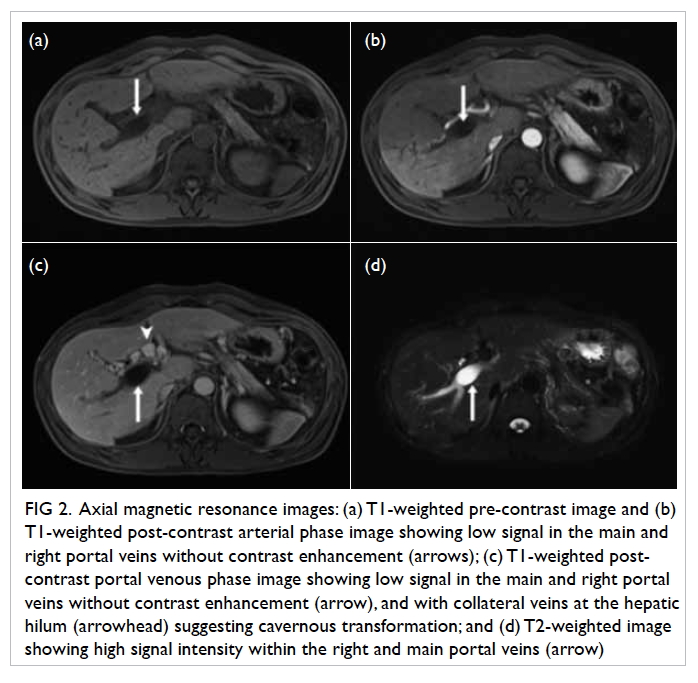

Figure 2. T2-weighted images showing (a) right and (b) left ovaries (arrows), which are normal in size and with small cysts

The majority of cystic pelvic masses originate from

the ovary. Mimics of ovarian cystic masses have a wide variety of

diagnoses. It is important to understand the relationship of a mass with

its anatomic location, identify normal ovaries at imaging, and correlate

imaging findings with the patient’s clinical history to avoid

misdiagnosis.

Retroperitoneal schwannoma is a rare tumour and is

difficult to diagnose, accounting for only 6% of retroperitoneal

neoplasms. A retroperitoneal schwannoma is usually located in the

paravertebral space or pre-sacral pelvic retroperitoneum.1 It usually occurs in young to middle-aged adults, and

women are affected twice as often as men.1

The patient is usually asymptomatic, or complains of a wide variety of

non-specific symptoms when the tumour is large in size.2 Malignant transformation is rare.1 On magnetic resonance images, a schwannoma appears as a

well-defined mass with hypo- or iso-intensity on T1-weighted images and

with hyperintensity on T2-weighted images. The nerve of origin is often

difficult to identify. It is not unusual for a schwannoma to display

cystic changes. However, prominent cystic changes are uncommon and point

to ancient schwannoma, a rare variant of schwannoma that is characterised

by degeneration and decreased cellularity.3

On magnetic resonance images, ancient schwannoma appears as a

well-defined, complex cystic mass with a variable enhancement pattern.

Thick T1 and T2 hypointense enhancing wall and septa correspond to a

fibrous capsule, consisting of epineurium and residual nerve fibres.4

Identification of the nerve adjacent to or along

the tumour is useful for differentiating ancient schwannomas from other

complex cystic lesions, such as serous or mucinous cystadenocarcinoma,

abscess, necrotic soft-tissue sarcoma, or necrotic metastatic

lymphadenopathy.5

In the present case, the patient did not complain

of any neurological symptoms at presentation. The presence of normal

ovaries and fibrous capsule indicated a preoperative diagnosis of ancient

schwannoma. This case illustrates the importance of considering this

uncommon diagnosis when a pelvic complex cystic lesion is detected in

imaging, and seeking specific imaging features (such as fibrous capsule

and close relationship to the nerve) to confirm or exclude this diagnosis.

This would facilitate surgical planning and minimise the risk of

complications such as major neurological deficit.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept or design,

acquisition of data, analysis or interpretation of data, drafting of the

manuscript, and critical revision for important intellectual content. All

authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved

the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its

accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of

interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Rha SE, Byun JY, Jung SE, Chun HJ, Lee

HG, Lee JM. Neurogenic tumors in the abdomen: tumor types and imaging

characteristics. Radiographics 2003;23:29-43. Crossref

2. Kim SH, Choi BI, Han MC, Kim YI.

Retroperitoneal neurilemoma: CT and MR findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol

1992;159:1023-6. Crossref

3. Dahl I. Ancient neurilemmoma

(schwannoma). Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand A 1977;85:812-8. Crossref

4. Takeuchi M, Matsuzaki K, Nishitani H,

Uehara H. Ancient schwannoma of the female pelvis. Abdom Imaging

2008;33:247-52. Crossref

5. Isobe K, Shimizu T, Akahane T, Kato H.

Imaging of ancient schwannoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004;183:331-6. Crossref