An uncommon complication of infective endocarditis

Hong Kong Med J 2015 Apr;21(2):187.e1–2

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144248

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PICTORIAL MEDICINE

An uncommon complication of infective endocarditis

KW Lam, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine); KW Au Yeung, MB, BS, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology); KY Lai, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)

Intensive Care Unit, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Jordan, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr KW Lam (lamkw1@ha.org.hk)

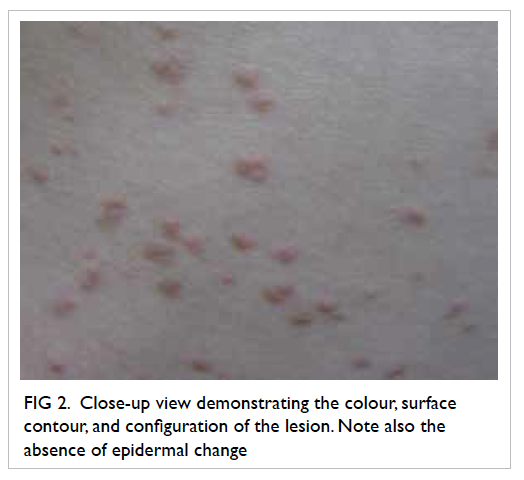

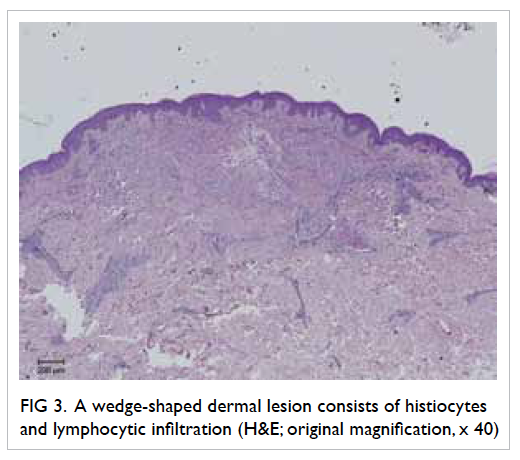

A 20-year-old man presented to us with confusion and

generalised skin rash in April 2010. On examination,

he was febrile and in shock. He was detected with a

mitral regurgitation murmur and mild neck stiffness.

His white cell count was elevated and platelet count

was low. His liver function was mildly impaired.

Chest X-ray showed acute pulmonary oedema.

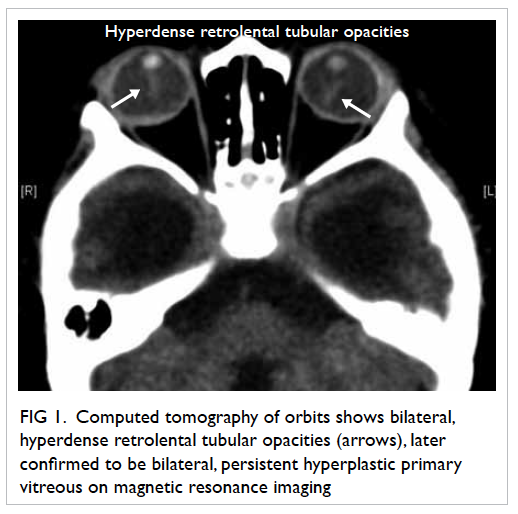

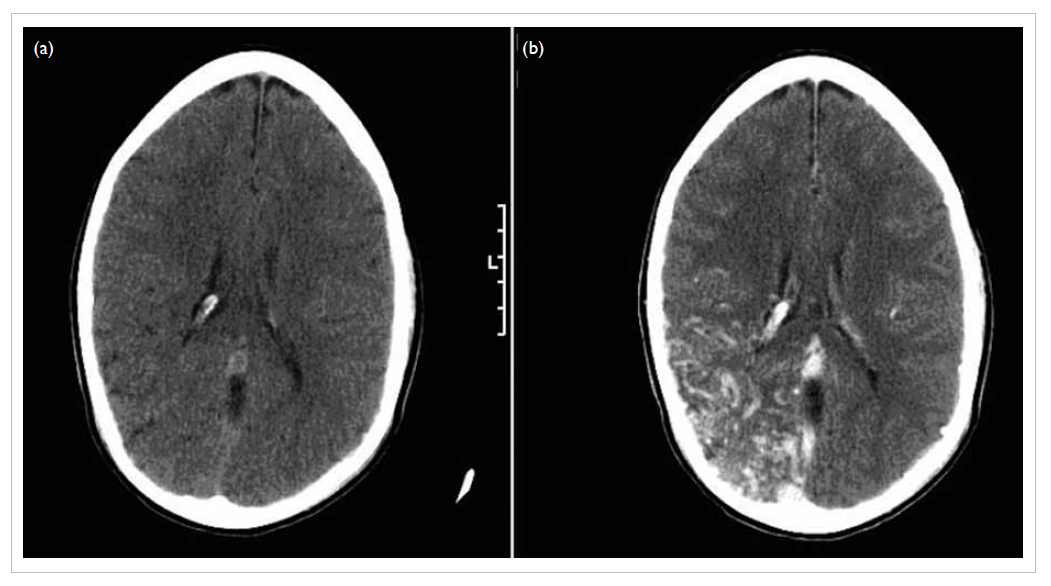

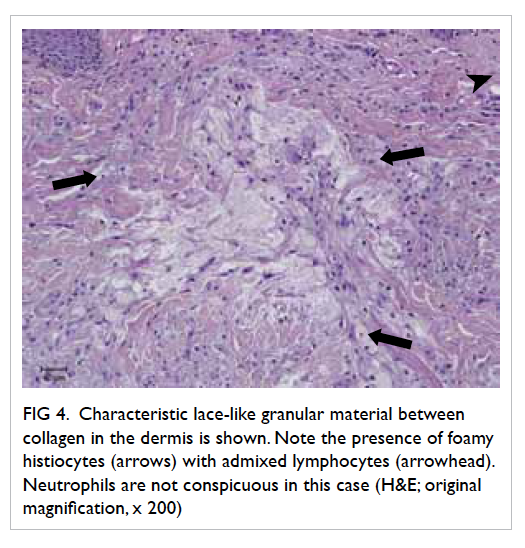

Computed tomography (CT) scan of brain showed

multiple haematomas in his left occipital lobe and

right parietal lobe, and subarachnoid haemorrhage

(Fig 1a). Blood culture showed methicillin-sensitive

Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA).

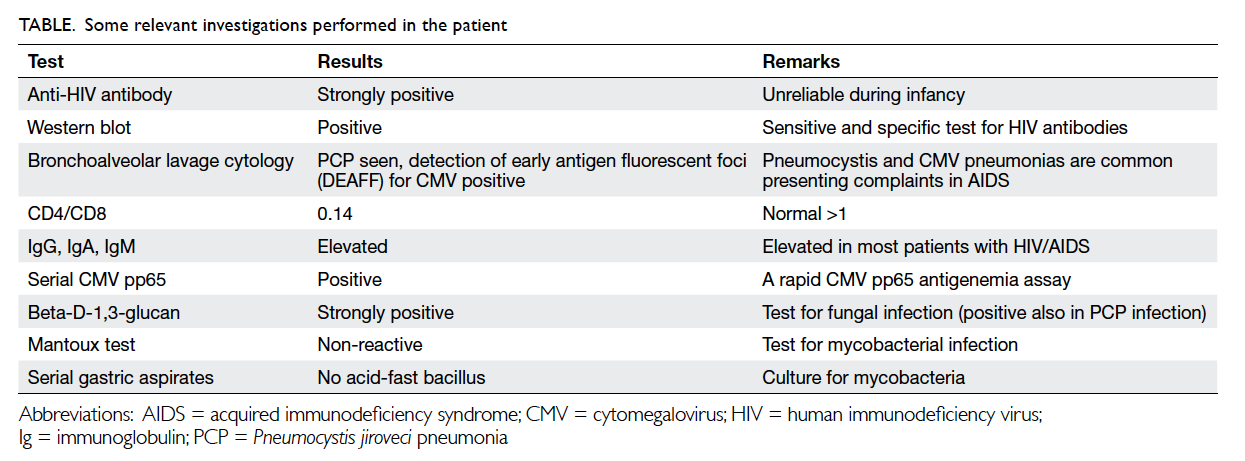

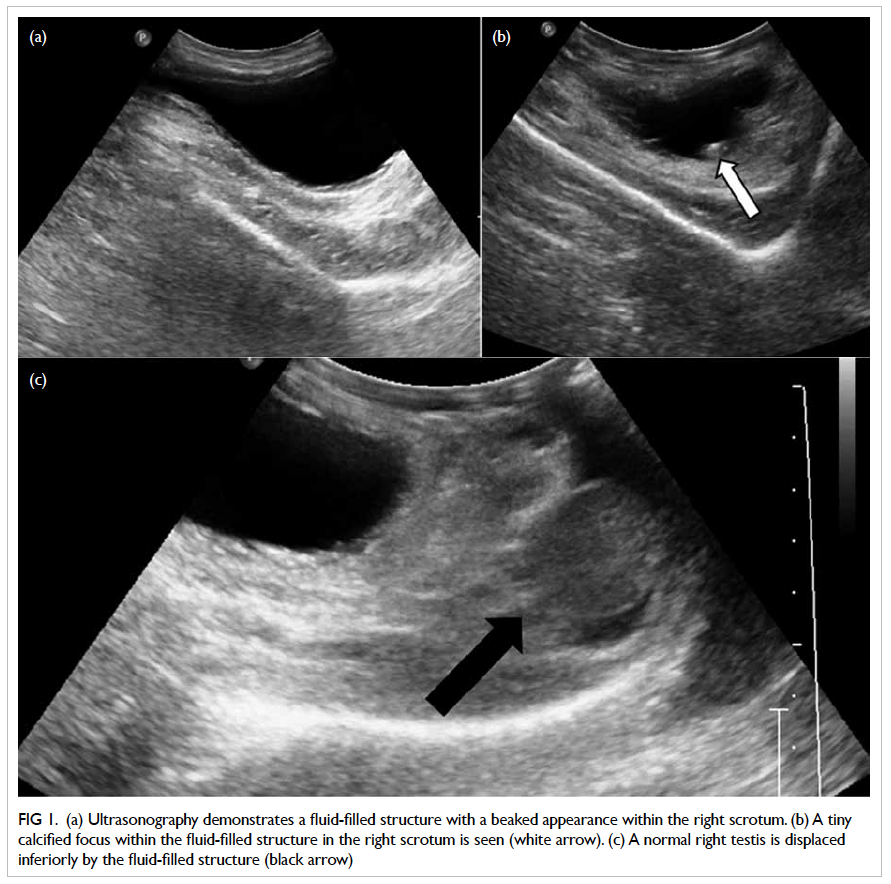

Figure 1. Complications of infective endocarditis developed by the patient: (a) cerebral haemorrhage in the left occipital lobe (arrows), (b) saddle embolism (arrow)

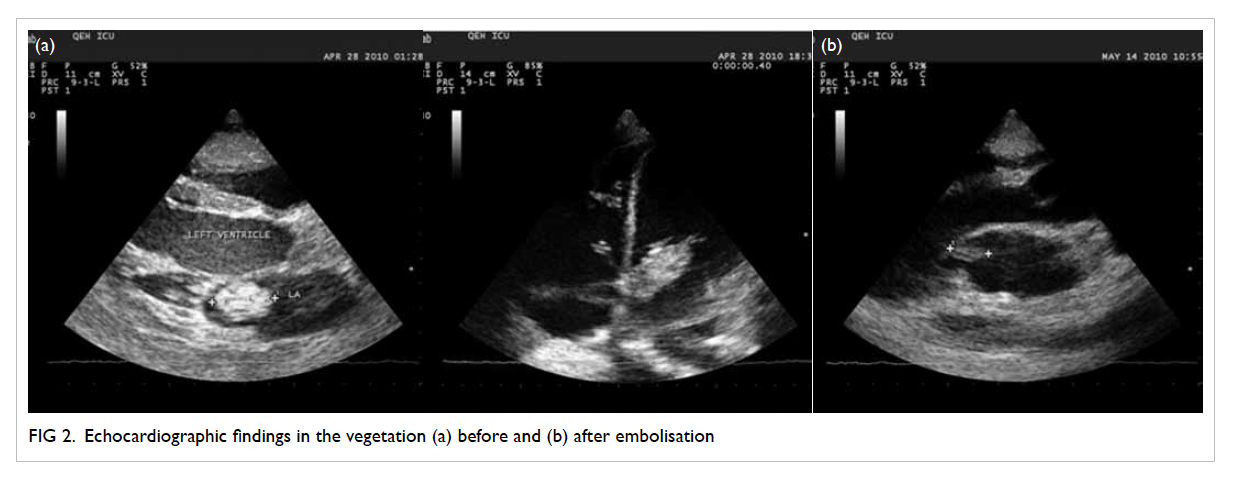

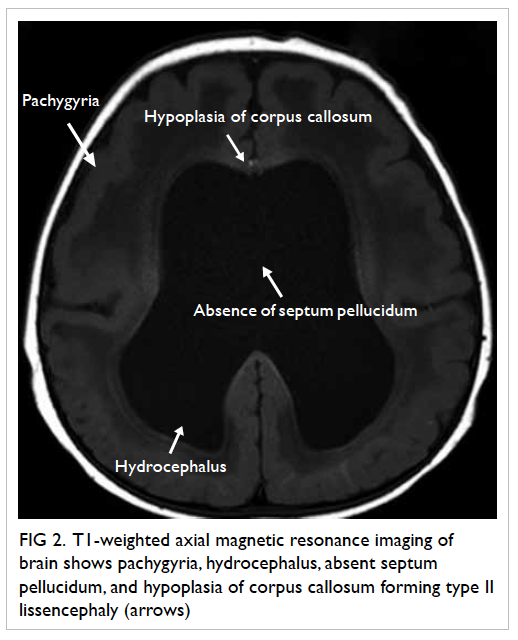

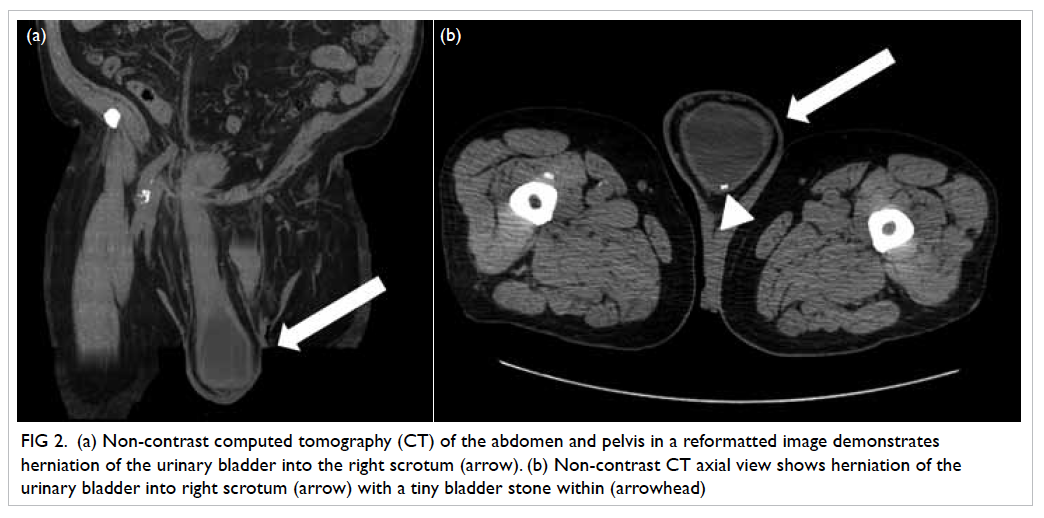

Transthoracic echocardiogram showed a huge

vegetation measuring 4 cm x 2.22 cm attached to

the base of anterior leaflet of mitral valve, resulting

in perforation of the base of leaflet with severe

mitral regurgitation (Fig 2a). The diagnosis was

infective endocarditis due to MSSA, complicated by

ruptured chordae tendineae with severe acute mitral

regurgitation and multiple, septic cerebral emboli.

The source of infection was suspected to be the skin.

He was treated with high-dose intravenous cloxacillin

and gentamicin. His heart failure was treated with

frusemide.

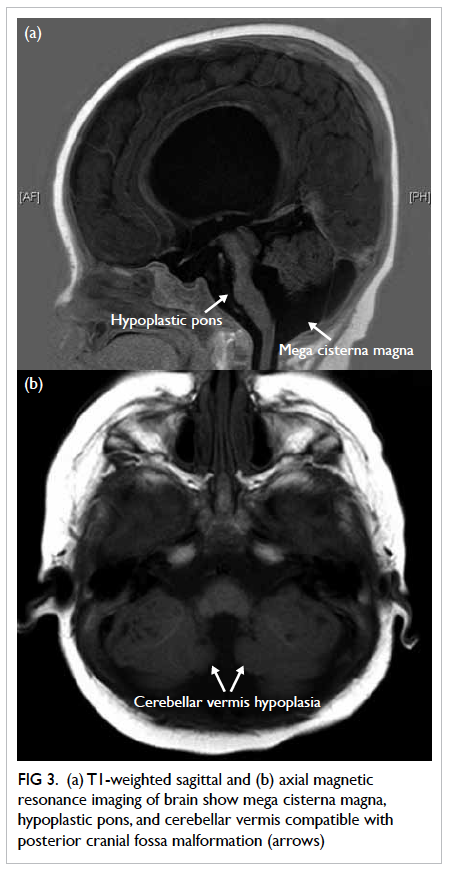

Three weeks later, he complained of sudden

onset of right lower limb pain and numbness. His

CT angiogram showed a large saddle embolus in the

lower abdominal aorta (Fig 1b). Emergent right-sided

lower femoral and bilateral iliac artery embolectomy

was performed.

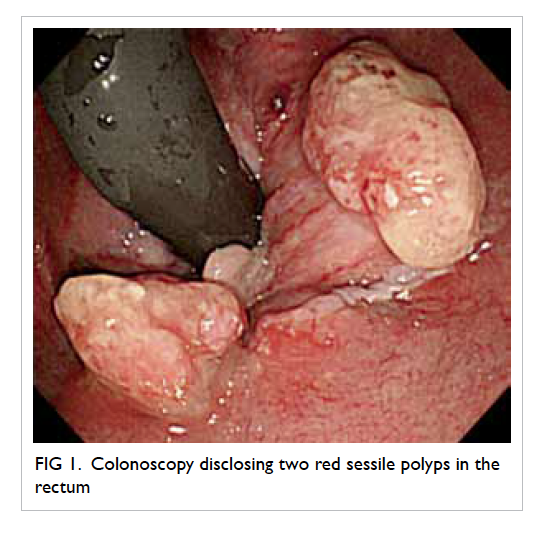

On postoperative echocardiogram, the size of

the vegetation was found to be decreased to 1.5 cm in

diameter (Fig 2b). He then underwent mitral valvular

replacement about 1 week later.

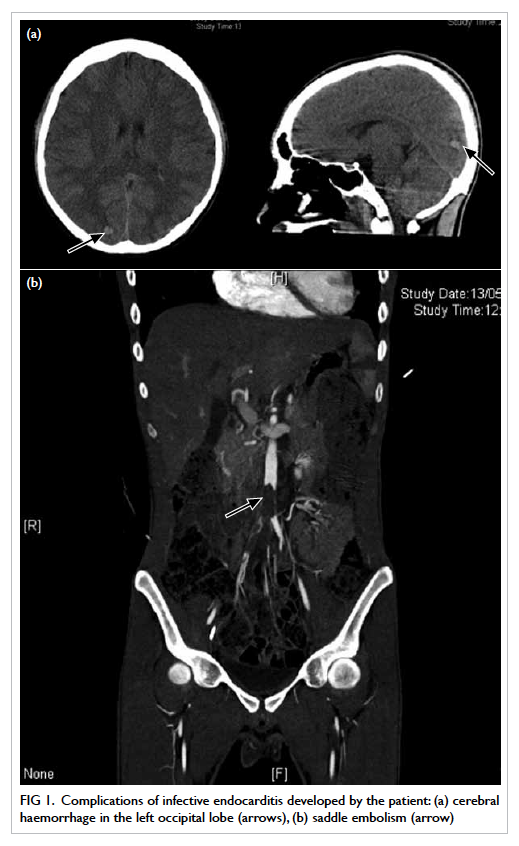

Discussion

The incidence of community-acquired native-valve

endocarditis in western countries ranges from 1.7

to 6.2 cases per 100 000 person-years, with a male-to-female ratio of 1.7:1.1 Recently, the incidence of S

aureus infective endocarditis is on the rise. Infective

endocarditis due to S aureus is more common among

young adults, especially the intravenous injection

drug users.1 Usually, the tricuspid valve is involved.2

Extra cardiac complications of infective

endocarditis usually include embolic events. The

rate of embolic events has a relationship with the

initiation of antibiotic therapy. In one study, after

the commencement of appropriate antimicrobial

treatment, the rate of embolism fell from 13 per 1000

patient-days during the first week of treatment to

fewer than 1.2 per 1000 patient-days 2 weeks after

treatment.3 A review involving 281 patients with

suspected infective endocarditis demonstrated that

the incidence of embolic events was greater with

mitral than aortic valve vegetations (25% vs 10%).4

For mitral valve vegetations, the rate of embolism was

higher if these were attached to the anterior leaflet

rather than posterior leaflet. Some studies showed

that the rate of embolism correlated with the size of

vegetation, with the risk being higher if the diameter

of the vegetation was greater than 1 cm.1

Up to 65% of embolic events of infective

endocarditis are associated with neurological

involvement. Such neurological complications

account for 20% to 40% of all patients with infective

endocarditis.5 Saddle embolus is a large embolus that

straddles the arterial bifurcation and, thus, blocks

both branches of the aorta. Saddle embolisation at

the aortic bifurcation is an uncommon but serious

complication. From the literature search, only eight

cases were reported and all were caused by fungal

endocarditis.6

References

1. Mylonakis E, Calderwood SB. Infective endocarditis in

adults. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1318-30. Crossref

2. Hecht SR, Berger M. Right-sided endocarditis in

intravenous drug users. Prognostic features in 102

episodes. Ann Intern Med 1992;117:560-6. Crossref

3. Heiro M, Nikoskelainen J, Engblom E, Kotilainen E,

Marttila R, Kotilainen P. Neurologic manifestations of

infective endocarditis: a 17-year experience in a teaching

hospital in Finland. Arch Inern Med 2000;160:2781-7. Crossref

4. Rohmann S, Erbel R, Görge G, et al. Clinical relevance of vegetation

localization by transoesophageal echocardiography in

infective endocarditis. Eur Heart J 1992;13:446-52.

5. Røder BL, Wandall DA, Espersen F, Frimodt-Møller

N, Skinhøj P, Rosdahl VT. Neurologic manifestations

in Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis: a review of

260 bacteremic cases in nondrug addicts. Am J Med

1997;102:379-86. Crossref

6. Kawamoto T, Nakano S, Matsuda H, Hirose H, Kawashima

Y. Candida endocarditis with saddle embolism: a

successful surgical intervention. Ann Thorac Surg

1989;48:723-4. Crossref