Dermatomyositis following COVID-19 vaccination

Hong Kong Med J 2025 Feb;31(1):74.e1–2 | Epub 10 Feb 2025

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PICTORIAL MEDICINE

Dermatomyositis following COVID-19 vaccination

TK Kong, FRCP, FHKAM (Medicine)

Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr TK Kong (tkkong@cuhk.edu.hk)

A 59-year-old Chinese woman, a workman with

hypertension and non-smoking history, sought

medical advice in April 2024 for a 16-month

history of progressive weight loss, reduced appetite,

proximal myalgia, arthralgia of the hands, abdominal

discomfort and constipation since February 2023;

and a 10-month history of dry cough and exertional

dyspnoea. She had received four Comirnaty

messenger ribonucleic acid coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19) vaccinations (Pfizer-BioNTech; Pfizer

Inc, Philadelphia [PA], United States) between 8 July

2021 and 12 January 2023 and had two COVID-19

infections, one each in March 2022 and June 2023.

She carried the beta thalassaemia trait, as did her

father. Both her parents had lung cancer.

Investigations in January 2024 revealed raised

carcinoembryonic antigen level (11.4 ug/L; reference

range, <5.0); negative stool for occult blood; negative

sputum for acid-fast bacilli smear/culture and

positive anti–nuclear antigen antibodies (1:160).

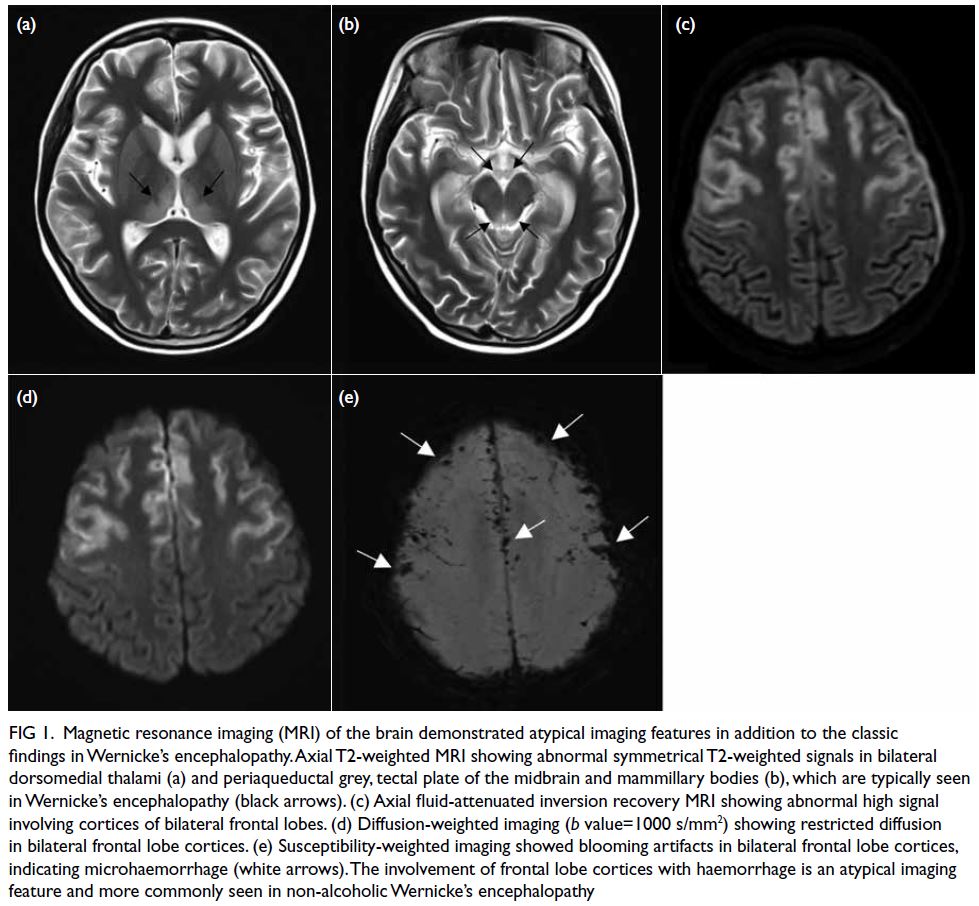

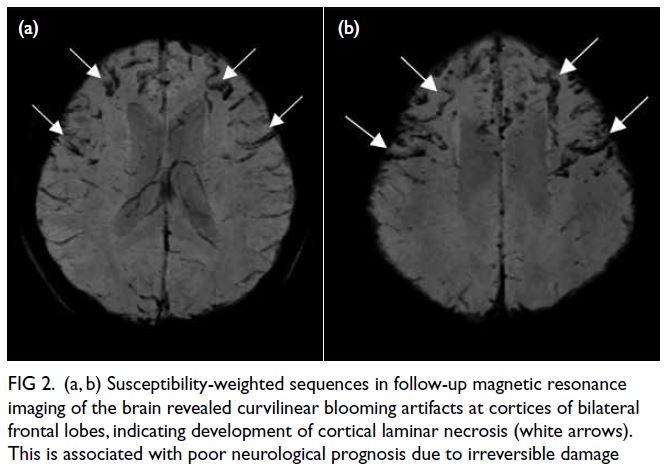

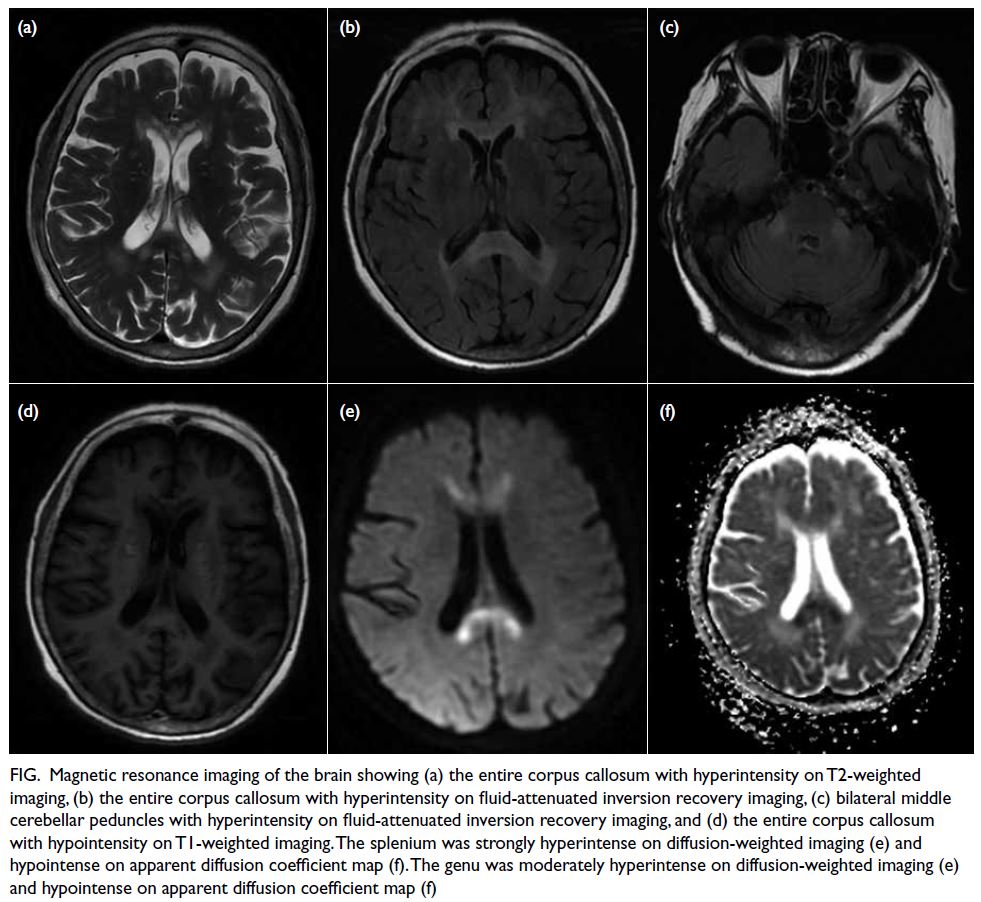

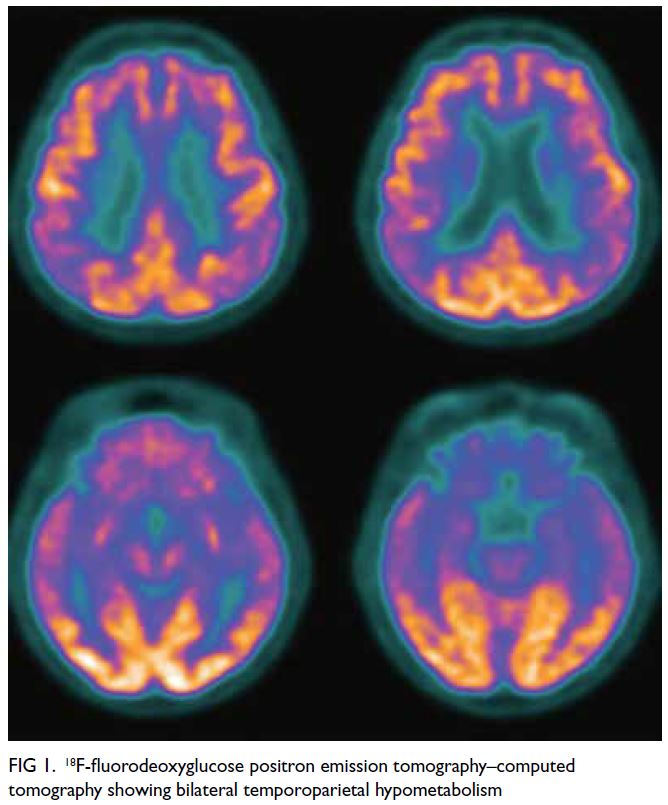

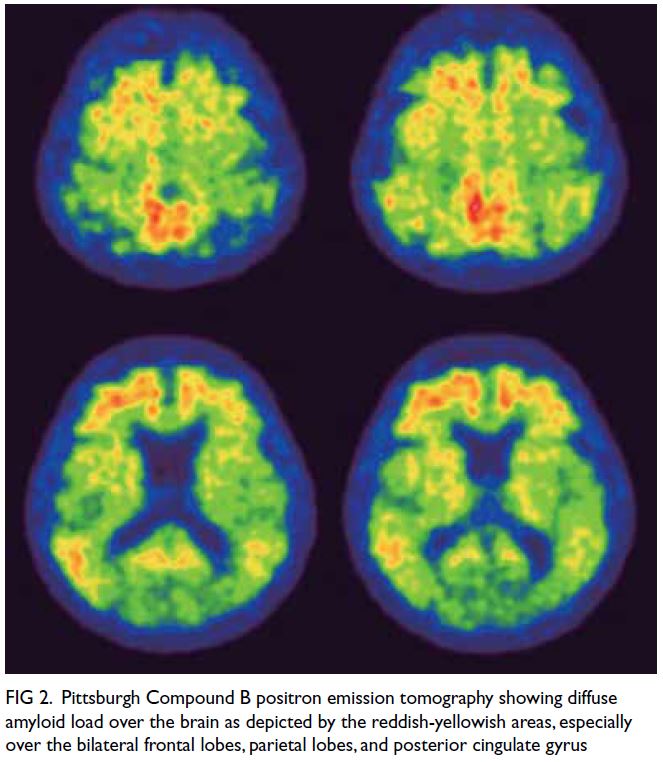

Whole-body positron emission tomography–computed tomography in January 2024 revealed

patchy ground-glass opacities and fibrosis with mild 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the lower lobes of

the lungs, but no hypermetabolic lesion to suggest

malignancy. Twelve days prior to consultation she

had been hospitalised for dizziness and found to

have a low haemoglobin level (6.7 g/dL). She was

transfused to 8.5 g/dL and discharged the next day.

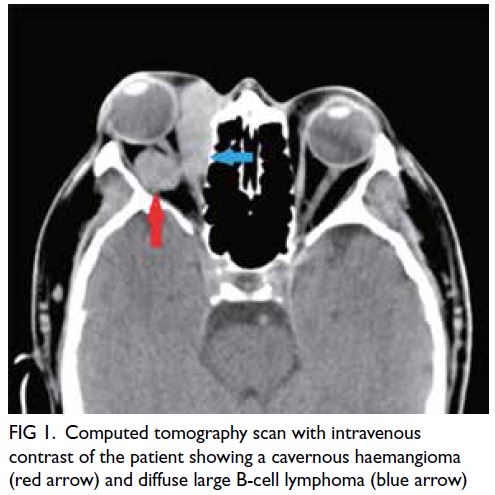

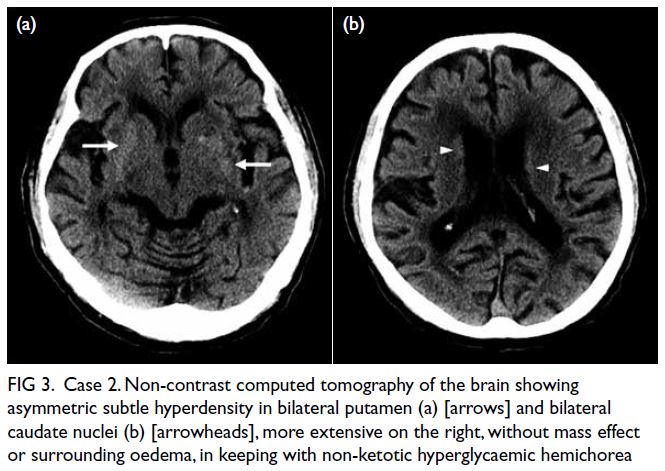

When seen at the clinic in April 2024, the

patient’s body weight was 47.9 kg, compared

with 68.2 kg 16 months previously. She expressed

difficulty with working and in getting up from

bed because of weakness. Physical examination

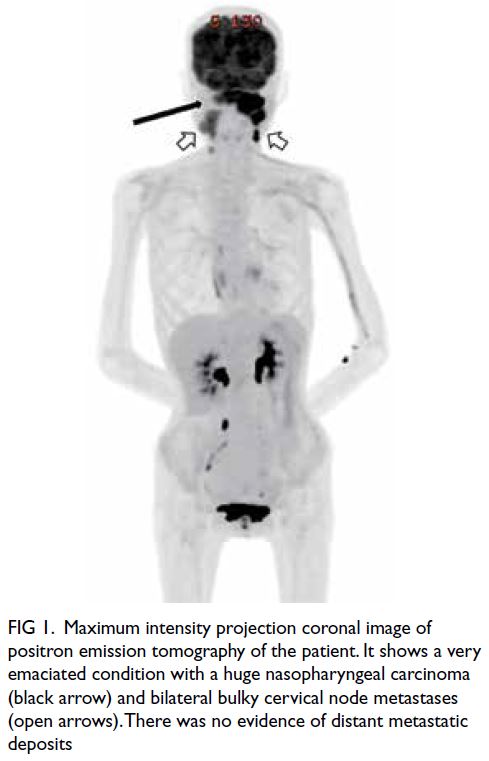

revealed pallor, a rash on her hands suggestive

of dermatomyositis (Fig), puffy eyelids without

heliotrope rash, and proximal muscle wasting and

weakness. Fine end-inspiratory crepitations were

heard at the base of the lungs. There was no cervical

lymphadenopathy nor palpable abdominal masses.

Review showed a serial drop in haemoglobin level

(from 10.2 g/dL in February 2023 to 6.7 g/dL in

April 2024), increasing microcytosis (decrease in

mean corpuscular volume from 63.1 fL in February

2023 to 59.0 fL in April 2024), and iron deficiency

in the setting of chronic inflammation. The clinical

diagnosis was dermatomyositis with myopathy,

interstitial lung disease, and probable colon cancer

with iron deficiency anaemia superimposed on

beta thalassaemia trait. She was referred to hospital

for further management. Muscle enzyme tests

revealed normal creatine kinase level (113 U/L)

but elevated lactate dehydrogenase (499 U/L) and

alanine aminotransferase levels (65 U/L). Myositis

antibody screening confirmed the diagnosis of

anti–melanoma differentiation–associated protein 5

(anti-MDA5) antibody–positive dermatomyositis.

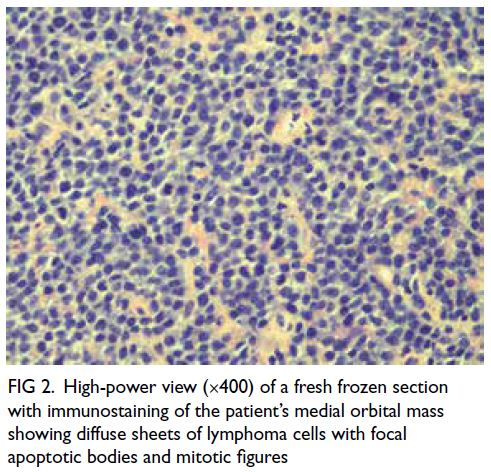

Figure. Rash on the patient’s hands characteristic of dermatomyositis: violaceous plaques over the knuckles and fingers (Gottron papules), periungual erythematous swelling, mechanic’s hands with fissuring and hyperkeratosis on the ulnar aspect of the thumbs and radial aspect of the index fingers

The patient’s illness onset in February 2023

following COVID-19 vaccination the month

before suggested a trigger by vaccination, further

aggravated by her COVID-19 infection in June

2023. Dermatomyositis, inflammatory myopathy,

and rheumatic immune-mediated inflammatory

diseases have been reported following COVID-19

vaccination and infection.1 2 3 In a systematic review

up to May 2023,3 24 cases of post–COVID-19

vaccination dermatomyositis were reported

worldwide, the majority following vaccination with

Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, and some following that

with Moderna and Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccines.

Only two such cases were reported among Chinese,

one from mainland China (after Sinopharm’s

inactivated Vero cell),4 one from Taiwan (after Oxford–AstraZeneca),5 but none from Hong Kong.

The close temporal sequence and surge against

a background of the reported case series suggest

an association between severe acute respiratory

syndrome coronavirus 2 infection/vaccination and

the development of dermatomyositis, although

proof of causality requires further research because

of the limited number of cases reported.1 3 A recent

bioinformatic study and transcriptome-derived

insights point to a potential causal link between the

surge in the Yorkshire region in the United Kingdom

between 2020 and 2022 in anti-MDA5–positive

dermatomyositis, autoimmune interstitial lung

disease and COVID-19.6 The COVID-19 vaccination

and infection may trigger a proinflammatory

immune response involving type I interferon and

stimulate production of dermatomyositis-specific

autoantibodies such as MDA5 that are closely related

to viral defence or viral RNA interaction supporting

the concept of infection and vaccination-associated

dermatomyositis.1 2 3 6

This case demonstrates that dermatomyositis

can be induced by COVID-19 vaccination, ignorance

of which and of the diagnostic clinical signs

would lead to delayed diagnosis and management.

Coronavirus disease 2019 vaccines are widely used.

When patients present with constitutional symptoms

with persistent muscle aches and weakness following

COVID-19 vaccination, clinicians should consider

dermatomyositis as a differential diagnosis and

examine the skin for pathognomonic signs.

Author contributions

The author is solely responsible for the concept or design,

acquisition of data, analysis or interpretation of data, drafting

of the manuscript, and critical revision of the manuscript for

important intellectual content. The author had full access to

the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version

for publication, and takes responsibility for its accuracy and

integrity.

Conflicts of interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration

of Helsinki. Patient consent was obtained for clinical photo of

her hands and for publication of the article.

References

1. Holzer MT, Krusche M, Ruffer N, et al. New-onset

dermatomyositis following SARS-CoV-2 infection

and vaccination: a case-based review. Rheumatol Int

2022;42:2267-76. Crossref

2. Ding Y, Ge Y. Inflammatory myopathy following

coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination: a systematic review.

Front Public Health 2022;10:1007637. Crossref

3. Nune A, Durkowski V, Pillay SS, et al. New-onset rheumatic

immune-mediated inflammatory diseases following SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations until May 2023: a systematic review.

Vaccines (Basel) 2023;11:1571. Crossref

4. Yang L, Ye T, Liu H, Huang C, Tian W, Cai Y. A case of

anti-MDA5–positive dermatomyositis after inactivated

COVID-19 vaccine. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol

2023;37:e127-9. Crossref

5. Huang ST, Lee TJ, Chen KH, et al. Fatal myositis,

rhabdomyolysis and compartment syndrome after

ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccination. J Microbiol Immunol

Infect 2022;55:1131-3. Crossref

6. David P, Sinha S, Iqbal K, et al. MDA5-autoimmunity

and interstitial pneumonitis contemporaneous with the

COVID-19 pandemic (MIP-C). EBioMedicine

2024:104:105136. Crossref