Tumour-induced osteomalacia

Hong Kong Med J 2014 Aug;20(4):350.e1–2

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj133981

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PICTORIAL MEDICINE

Tumour-induced osteomalacia

Anjali A Bhatt, MD1; Suma S Mathews, MS, DLO2; Anusha Kumari, MD3; Thomas V Paul, MD, PhD1

1 Department of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism, Christian Medical College, Vellore 632 004, India

2 Department of ENT, Christian Medical College, Vellore 632 004, India

3 Department of General Pathology, Christian Medical College, Vellore 632 004, India

Corresponding author: Dr Thomas V Paul (thomasvpaul@yahoo.com)

Tumour-induced osteomalacia (also known as

oncogenic osteomalacia) is an uncommon condition.

The fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23), a

polypeptide secreted by mesenchymal tumours,

causes phosphaturia, which in turn results in

defective mineralisation. In addition, FGF-23 causes suppression of the enzyme 1α-hydroxylase located

in the proximal convoluted tubules of kidneys and

responsible for final activation of vitamin D (from

25-hydroxyvitamin D to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D).1

Once the tumour causing the osteomalacia is found,

its excision usually results in complete remission of

the bone disorder.2 Herein we report on a patient

who presented to us with the features of oncogenic

osteomalacia.

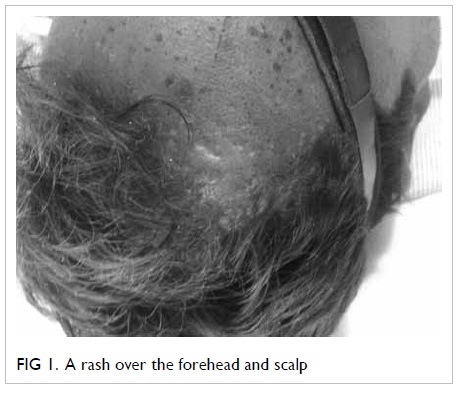

A 32-year-old woman born of non-consanguineous

parents complained of gradually

increasing proximal muscle weakness of both lower

limbs over 1 year in February 2012. She also had pain

in both hips while walking, which restricted her daily

activities. She had no history of any chronic gastro-intestinal

illness, and was not taking medication

which might affect bone metabolism. Nor was

there a family history of any similar illness. Clinical

examination revealed severe proximal muscle

weakness in both lower limbs. Active movements

like external rotation and abduction at the both

hips were painful. Otherwise the examination was

unremarkable.

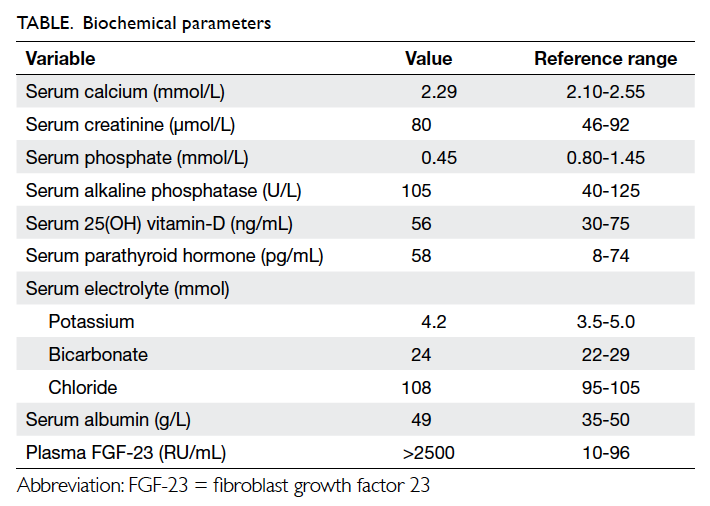

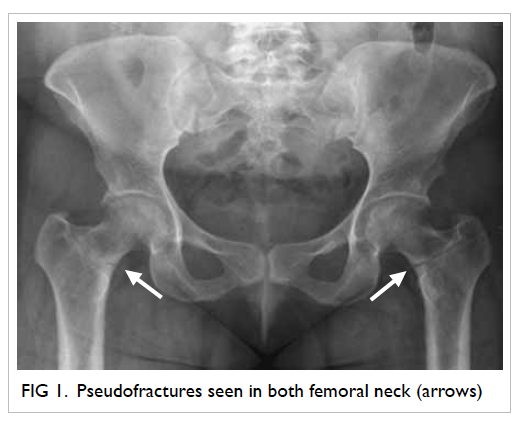

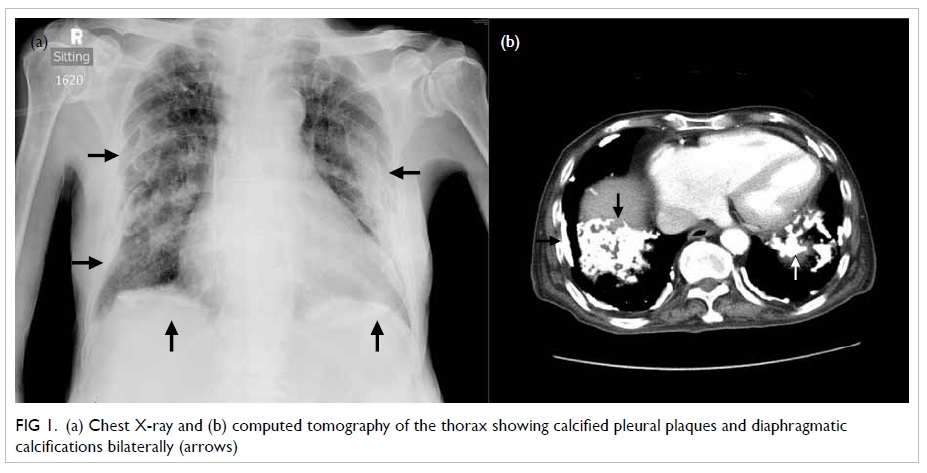

Biochemical evaluation revealed hypophosphataemia

with phosphaturia (Table). Radiology

of the hips showed bilateral femoral neck pseudofractures (Fig 1). These abnormalities favoured a

diagnosis of hypophosphataemic osteomalacia.

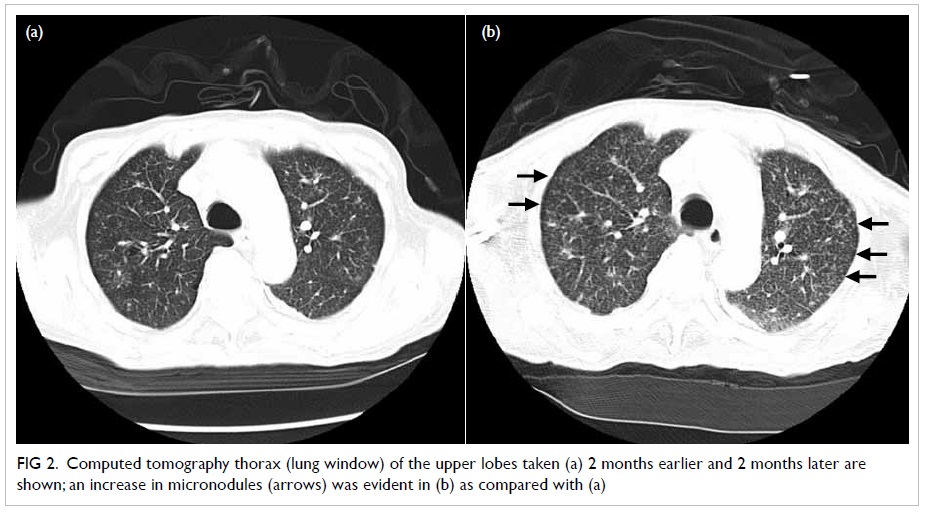

Further workup yielded a high FGF-23 level and

computed tomography of the paranasal sinuses

showed a soft tissue tumour in the left ethmoidal

sinus (Fig 2).

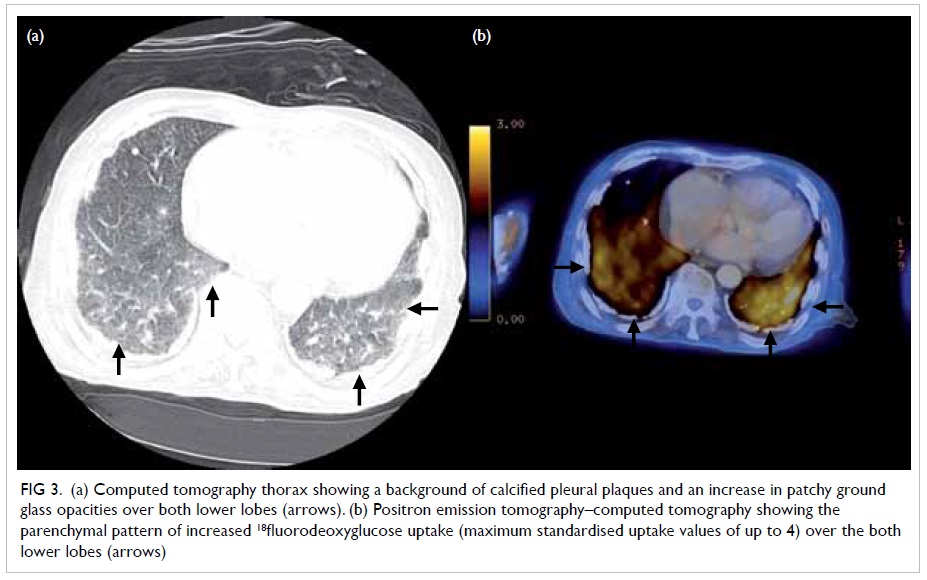

The patient was treated with phosphate

supplements and underwent complete excision of

the left ethmoidal sinus mass. Histopathological

examination confirmed the diagnosis of a phosphaturic mesenchymal tumour. The patient

remained stable after surgery. Two months later

she was asymptomatic, by which time her muscle

weakness had resolved markedly. Respective serial

serum phosphate concentrations were 0.90, 1.00, and

1.35 mmol/L at 1, 2 and 4 weeks after surgery. After

surgery, her plasma FGF-23 levels were undetectable.

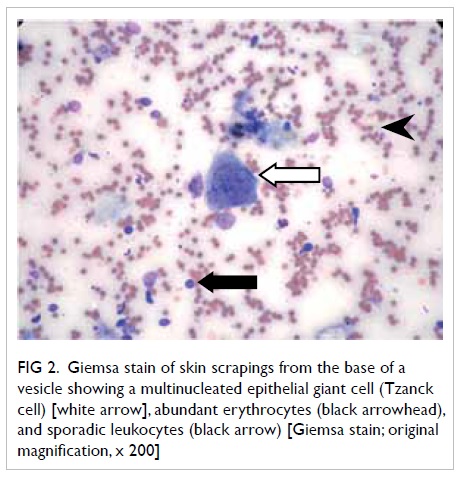

Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumours are rare

mesenchymal tumours and mostly comprised of

a single histological entity with mixed connective

tissue (designated PMT-MCT). Such tumours can

occur in the soft tissue or bone.3 Most PMT-MCTs

are histologically and clinically benign with rare

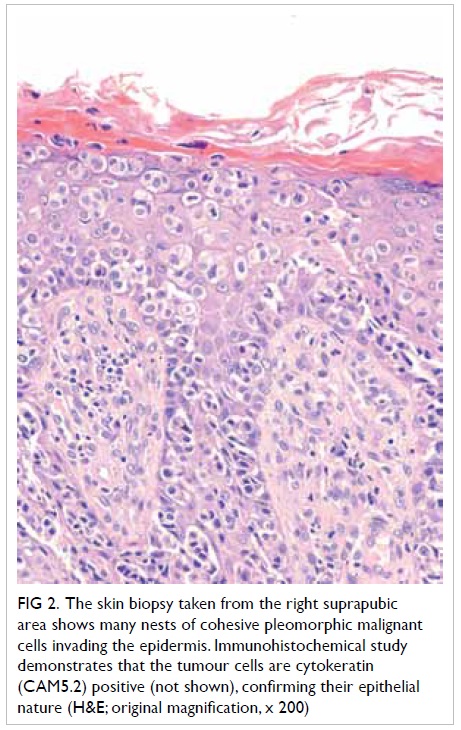

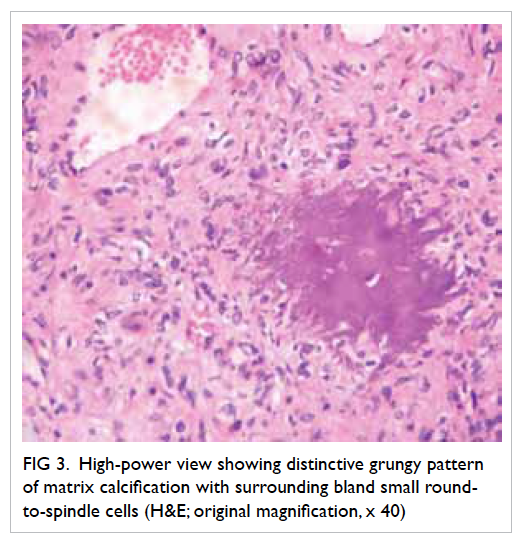

instances of malignancy. Microscopically, PMT-MCTs

are variable in appearance, usually being

composed of small, bland round-to-spindle cells embedded in a vascular to myxochondroid matrix

with variable amounts of mature adipose tissue (Fig

3). This matrix calcifies in an unusual ‘grungy’ fashion,

inciting an osteoclast-rich and fibrohistiocytic

response. A very prominent feature of PMT-MCT is

its elaborate intrinsic microvasculature. Malignant

PMT-MCTs resemble undifferentiated pleomorphic

sarcomas or fibrosarcomas.3 After complete excision

of the tumour, most patients improve dramatically4

and become symptomatically, biochemically, and

radiologically better. Such results should prompt

the physicians to search for such treatable and

potentially curable causes, whenever they encounter

hypophosphataemic osteomalacia.

Figure 3. High-power view showing distinctive grungy pattern of matrix calcification with surrounding bland small round-to-spindle cells (H&E; original magnification, x 40)

References

1. Chokyu I, Ishibashi K, Goto T, Ohata K. Oncogenic

osteomalacia associated with mesenchymal tumor in

the middle cranial fossa: a case report. J Med Case Rep

2012;6:181. CrossRef

2. Komínek P, Stárek I, Geierová M, Matoušek P, Zeleník K. Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumour of the sinonasal area:

case report and review of the literature. Head Neck Oncol

2011;3:16. CrossRef

3. Folpe AL, Fanburg-Smith JC, Billings SD, et al. Most

osteomalacia-associated mesenchymal tumors are a

single histopathologic entity: an analysis of 32 cases and a

comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol

2004;28:1-30. CrossRef

4. Chong WH, Molinolo AA, Chen CC, Collins MT. Tumor-induced

osteomalacia. Endocr Relat Cancer 2011;18:R53-77. CrossRef