Hong

Kong Med J 2018 Dec;24(6):634–5.e1–4

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj176964

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PICTORIAL MEDICINE

Magnetic resonance imaging monitoring of post-treatment

changes to Crohn’s disease–related anal fistula in patients prescribed

infliximab

KY Man, MB, ChB, FRCR1; Esther MF Wong,

MB, BS, FHKCR1; Francis KY Cho, MB, BS, FHKCR1; CM

Leung, FHKAM (Medicine)2

1 Department of Radiology, Pamela Youde

Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong

2 Department of Medicine, Pamela Youde

Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr KY Man (dsgundam@hotmail.com)

The incidence of inflammatory bowel disease,

particularly Crohn’s disease, is rising in Hong Kong.1 The age-adjusted incidence of Crohn’s disease increased

from 0.01 per 100 000 population in 1985 to 1.46 per 100 000 population in

2014.1 Crohn’s disease is a

multisystem disorder with specific radiological features such as

transmural inflammation, fistulation, and skip lesions. Perianal fistulas

often complicate Crohn’s disease, affecting up to 36% of patients.2

Infliximab, a monoclonal antibody against tumour

necrosis factor-α, has revolutionised the treatment of Crohn’s

disease–related anal fistula. Current evidence shows encouraging results

for closure of perianal fistulas. According to a local consensus

statement, biologics are advocated in patients with active fistulising

Crohn’s disease, particularly those with complex perianal fistulising

disease.3

Response to monoclonal antibody therapy needs to be

monitored. This pictorial review illustrates the post-treatment changes on

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of anal fistula in patients prescribed

infliximab.

Patients with a known history of Crohn’s disease

complicated by perianal fistula and prescribed infliximab between 2012 and

2016 were reviewed. The treatment regimen at our centre comprises an

intravenous loading dose of infliximab 5 mg/kg, followed by the same dose

at week 2 and week 6. Thereafter a maintenance dose of 5 mg/kg is given

every 8 weeks.

Magnetic resonance images were acquired with the

1.5T Siemens Magnetom Avanto system (Erlangen, Germany). The pelvic MRI

protocol for perianal fistula evaluation consists of T1-weighted and

high-spatial-resolution T2-weighted imaging sequences without fat

saturation to delineate the muscle groups, fat planes, and fistula tract.

T2-weighted imaging with fat suppression is used to assess oedema and

fluid-containing tracts and cavities, whereas fat-suppressed T1-weighted

unenhanced and contrast-enhanced sequences are used to assess the presence

and degree of inflammation (Table). Diffusion-weighted imaging is not routinely

performed in view of the need for an extended examination time.

Information about the presence of fluid, oedema, cavities, and

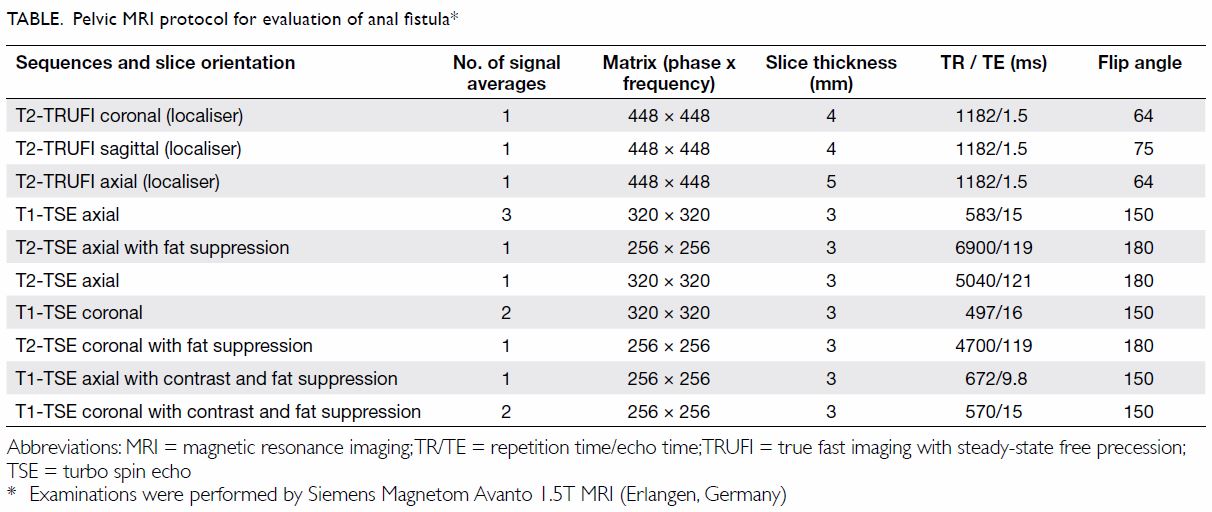

inflammation can be obtained through these sequences. Anal fistulae are

classified according to the Parks’ classification system (Fig

1).4

Figure 1. Schematic diagram demonstrating different types of perianal fistula according to Parks’ classification. Internal sphincter (thin arrow); external sphincter (thick arrow); puborectalis (asterisk); and levator ani (curved arrow). Intersphincteric fistula tracks between internal and external sphincter (1); trans-sphincteric fistula pierces through the external sphincter (2); suprasphincteric fistula tracks superior to the puborectalis (3); and extrasphincteric fistula penetrates the levator ani (4)

Three patients (two men, one woman) were reviewed

and all received infliximab. At least one pre-treatment and one

post-treatment MRI were performed.

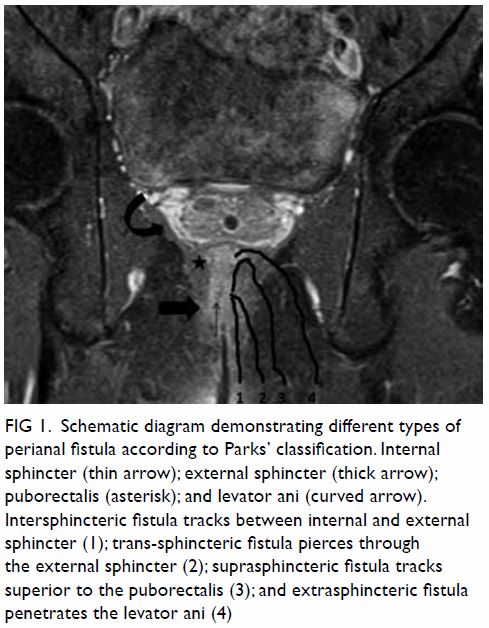

Patient A was a 34-year-old woman with a history of

systemic lupus erythematosus, retinitis, and neuropsychiatric lupus. She

had had recurrent ischiorectal abscess and perianal fistula since 2002.

Rectal biopsy confirmed Crohn’s disease. Despite treatment with

azathioprine, the perianal fistula failed to close. She was scheduled to

initially receive three doses of infliximab. Close monitoring was

essential in view of the potential to develop lupus-like disease. Progress

MRI after the third dose of infliximab showed slight interval improvement

in her perianal fistula. Biologics were continued in view of the residual

disease. After the seventh dose of infliximab, progress MRI revealed a

largely quiescent perianal fistula (Fig 2). In view of the radiologically healed

fistula, clinical improvement and potential risk of lupus-like disease,

the decision was taken to stop the infliximab infusion but continue close

clinical and radiological monitoring.

Figure 2. Patient A. (a and b) T2-weighted axial and T1-weighted post-contrast fat suppression axial magnetic resonance images showing an active trans-sphincteric tract at the 8 o’clock position with T2-weighted hyperintense signal and contrast enhancement (arrows). (c and d) One-year post-treatment. Loss of T2-weighted hyperintense signal and contrast enhancement suggested quiescent disease (arrows)

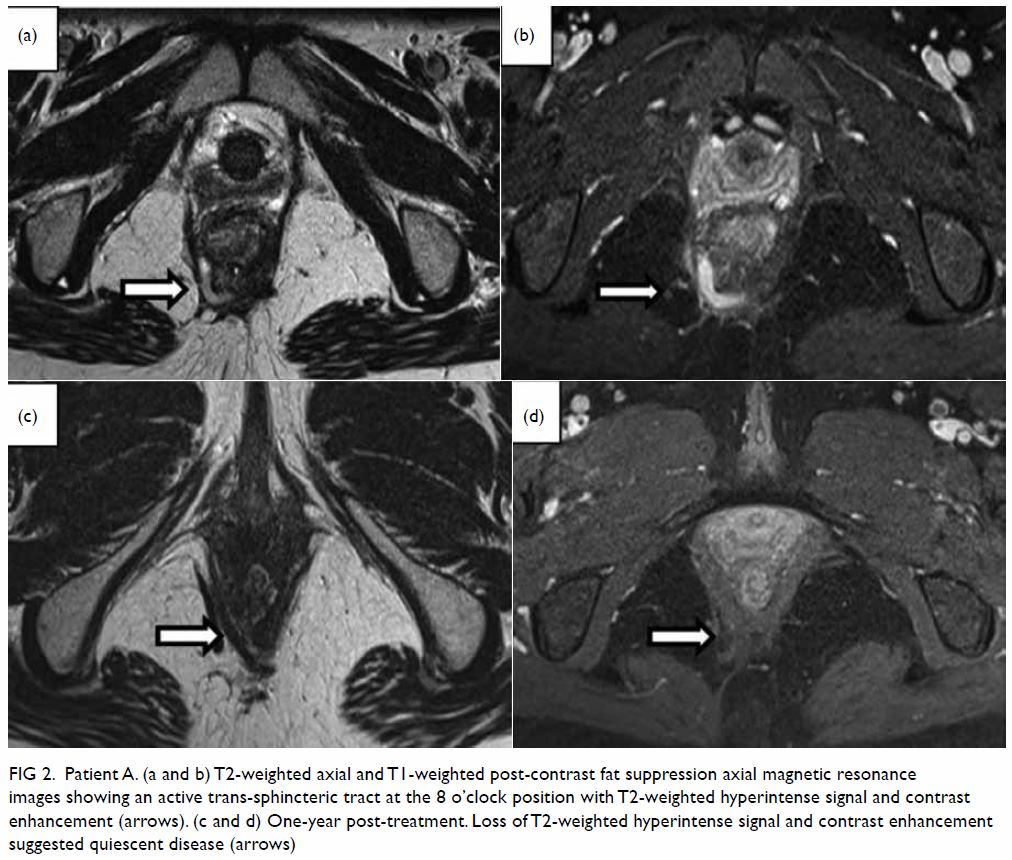

Patient B was a 24-year-old man with a history of

perianal fistula since 2015 and an episode of perianal abscess that

required incision and drainage. Crohn’s disease was confirmed on rectal

biopsy. He had previously developed azathioprine-induced pancytopenia.

Subsequent infusion of infliximab infusion resulted in responsive disease,

evident on MRI (Fig 3). Clinical and radiological monitoring

(progress MRI) at 6-month intervals was carried out to determine progress

of the perianal fistula. Infliximab would be stopped when there was

evidence of healed tract and clinical improvement.

Figure 3. Patient B. (a and b) T2-weighted axial and T1-weighted post-contrast fat suppression coronal magnetic resonance images showing an active intersphincteric tract at the right-sided natal cleft with T2-weighted hyperintense signal and contrast enhancement (arrows). (c and d) Six months post-treatment. Loss of T2-weighted hyperintense signal and contrast enhancement suggested quiescent disease (arrows)

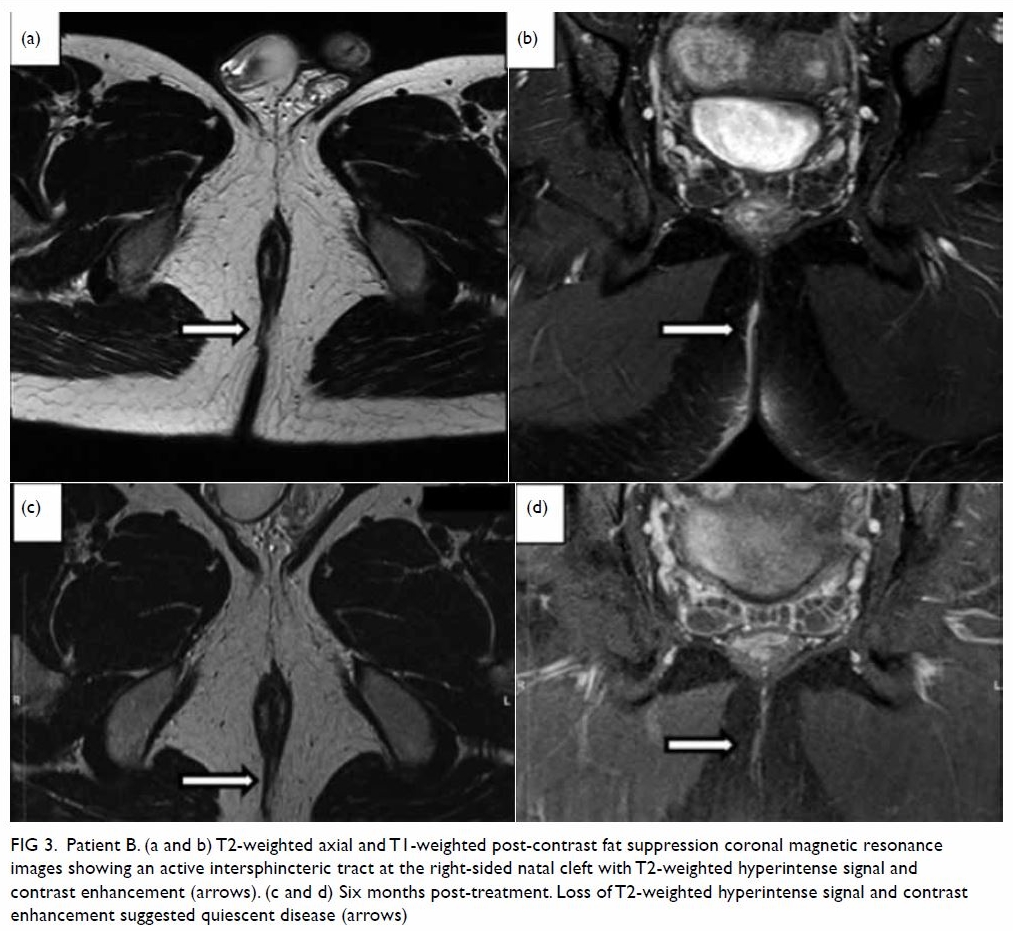

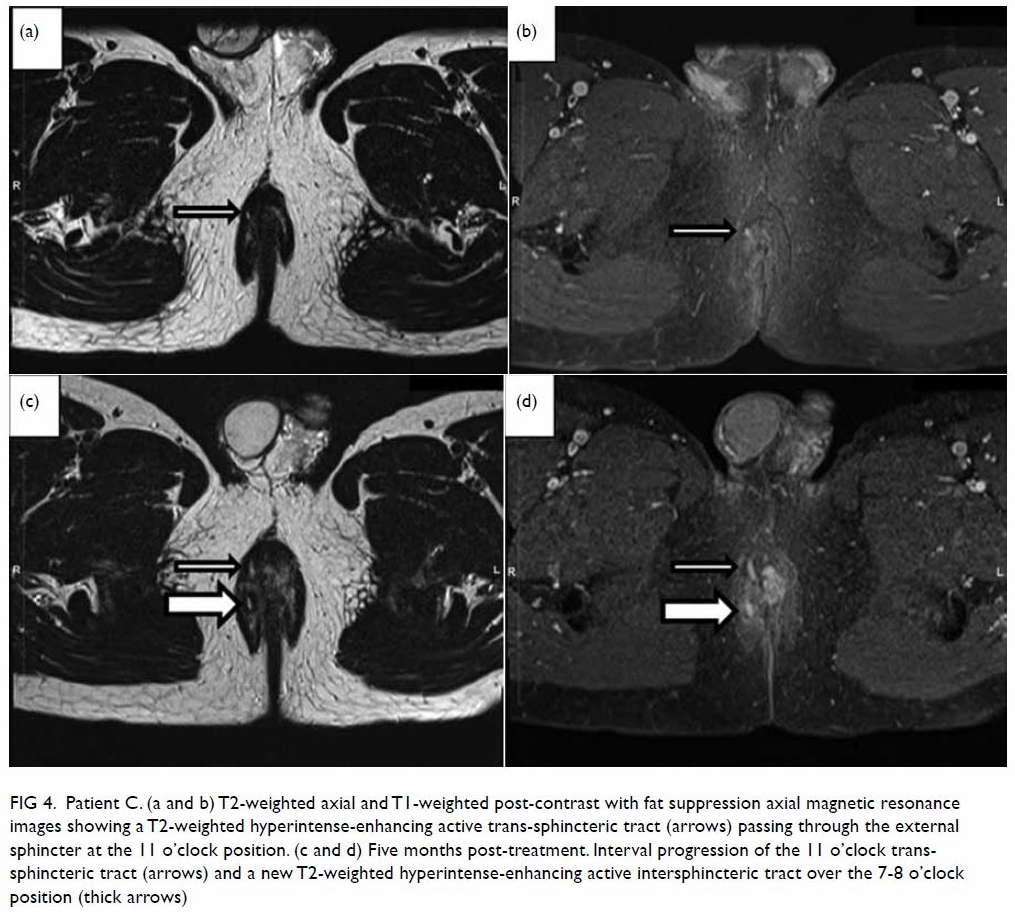

Patient C, a 42-year-old man had a history of

ileocolic Crohn’s disease since 2008, with episodes of perianal abscess

and fistula refractory to steroid and azathioprine treatment. Magnetic

resonance imaging showed progressive perianal fistula (Fig

4) after the second maintenance dose of infliximab. Previous

infliximab dose/frequency was continued and progress MRI planned for the

purpose of reassessment and consideration of alternative treatment if

there was persistent progression.

Figure 4. Patient C. (a and b) T2-weighted axial and T1-weighted post-contrast with fat suppression axial magnetic resonance images showing a T2-weighted hyperintense-enhancing active trans-sphincteric tract (arrows) passing through the external sphincter at the 11 o’clock position. (c and d) Five months post-treatment. Interval progression of the 11 o’clock transsphincteric tract (arrows) and a new T2-weighted hyperintense-enhancing active intersphincteric tract over the 7-8 o’clock position (thick arrows)

Crohn’s disease–related anal fistulae are

frequently encountered in radiologic practice due to their complexity and

propensity for incomplete treatment response and relapse.

Magnetic resonance imaging is a well-established

diagnostic tool for anal fistula. Its inherent high spatial and contrast

resolution allows precise anatomical delineation.5

Magnetic resonance imaging plays a critical role in helping determine the

appropriate treatment that should be individualised according to the type

of perianal fistula and the degree of involvement of surrounding pelvic

structures. Clinical examination can often be difficult because of

induration and inflammation in patients with anal sepsis. At MRI,

identification and localisation of the entire fistula, including the

external opening, the primary track, secondary tracks, abscesses, and the

internal opening, are essential for fistula classification and treatment.

Inadequate assessment may result in progression of a simple fistula to a

complex fistula, and failure to recognise secondary extensions can result

in recurrent sepsis. Anti–tumour necrosis factor antibodies (infliximab)

have been introduced with good clinical results. Magnetic resonance

imaging also plays an important role in evaluation of the response to

medical therapy. Magnetic resonance imaging does not have field of view

limitations and offers excellent views of the supralevator, retrorectal

and anteroanal spaces, where occult sepsis may be missed clinically due to

extensive scarring or a remote location.6

This pictorial review demonstrates the ability of

MRI to monitor the response to therapy of anal fistula in Crohn’s disease

patients receiving infliximab.

Author contributions

KY Man is responsible for the design, acquisition

and interpretation of data, and drafting of the article. EMF Wong, FKY

Cho, and CM Leung are responsible for critical revision for important

intellectual content.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of

interest. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility

for its accuracy and integrity.

References

1. Ng SC, Leung WK, Shi HY, et al.

Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease from 1981 to 2014: results from

a territory-wide population-based registry in Hong Kong. Inflamm Bowel Dis

2016;22:1954-60. Crossref

2. Leong RW, Lau JY, Sung JJ. The

epidemiology and phenotype of Crohn’s disease in the Chinese population.

Inflamm Bowel Dis 2004;10:646-51. Crossref

3. Leung WK, Ng SC, Chow DK, et al. Use of

biologics for inflammatory bowel disease in Hong Kong: consensus

statement. Hong Kong Med J 2013;19:61-8.

4. Parks AG, Gordon PH, Hardcastle JD. A

classification of fistula-in-ano. Br J Surg 1976;63:1-12. Crossref

5. Buchanan G, Halligan S, Williams A, et

al. Effect of MRI on clinical outcome of recurrent fistula-in-ano. Lancet

2002;360:1661-2. Crossref

6. Bell SJ, Halligan S, Windsor AC,

Williams AB, Wiesel P, Kamm MA. Response of fistulating Crohn’s disease to

infliximab treatment assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. Aliment

Pharmacol Ther 2003;17:387-93. Crossref