Indocyanine green angiography and lymphography in microsurgical subinguinal varicocelectomy with evolving video microsurgery and fluorescence imaging platforms

Hong Kong Med J 2022 Apr;28(2):181.e1–2

Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PICTORIAL MEDICINE

Indocyanine green angiography and

lymphography in microsurgical subinguinal

varicocelectomy with evolving video

microsurgery and fluorescence imaging platforms

CL Cho, FRCSEd (Urol), FHKAM (Surgery)1; Ringo WH Chu, FRCSEd (Urol), FHKAM (Surgery)2

1 SH Ho Urology Centre, Department of Surgery, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

2 Private Practice

Corresponding author: Dr CL Cho (chochaklam@yahoo.com.hk)

Intra-operative use of indocyanine green (ICG)

angiography and lymphography has been reported as

a valuable adjunct during microsurgical subinguinal

varicocelectomy (MSV).1 The development of a

video microsurgery platform and fluorescence

imaging technology further facilitates identification

of testicular arteries and lymphatics. We report

the intra-operative imaging of two patients who

underwent varicocele repair for grade 3 left

varicoceles in February and March 2021 using the

new platform.

The operations were performed under three-dimensional

(3D) optical magnification images on

the television monitors using the video microsurgery

platform with VITOM® 3D system (KARL STORZ

SE, Tuttlingen, Germany) as previously described.2

A pack of 25 mg ICG (Diagnogreen; Daiichi Sankyo

Co, Tokyo, Japan) was dissolved in 10 mL water.

Identification of testicular arteries was assisted by

ICG angiography with intravenous injection of 2 mL

(5 mg) ICG solution. After preservation of the

testicular arteries, the differentiation between

lymphatics and small veins was facilitated by

ICG lymphography performed following intra-parenchymal

testicular injection of 0.5 mL (1.25 mg)

ICG solution followed by gentle testicular massage.3 The setting of ICG fluorescence imaging consisted

of an IMAGE1 S™ 4U RUBINA™ with 4K 3D

monitor system (KARL STORZ SE, Tuttlingen,

Germany) and a HOPKINS™ Straight Forward

Telescope 0° (10-mm diameter/20-cm length)

[KARL STORZ SE, Tuttlingen, Germany]. We

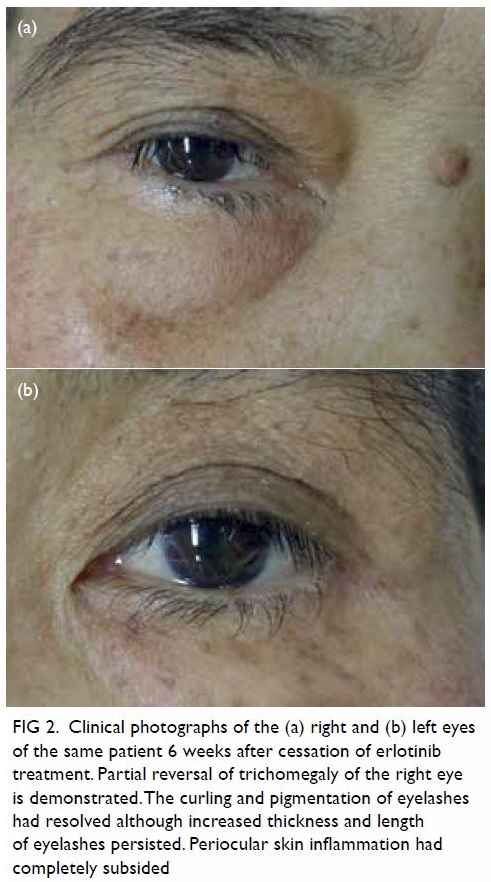

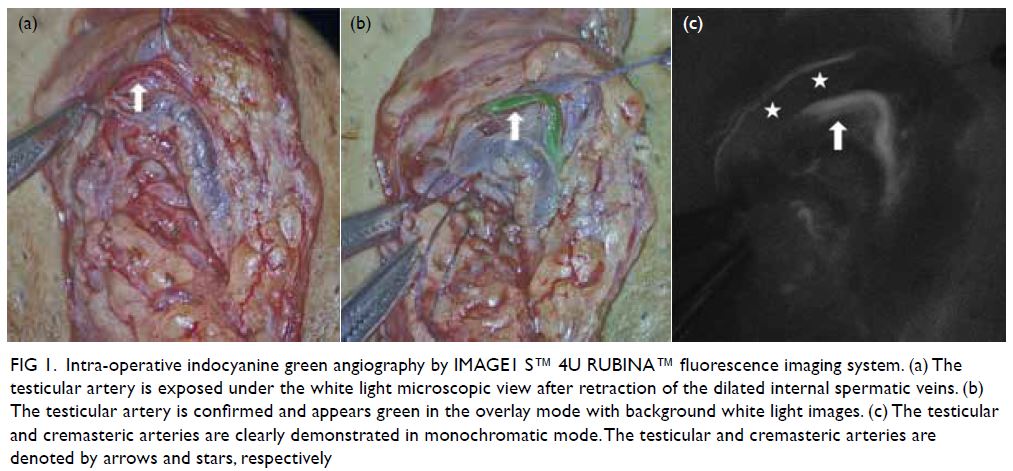

demonstrate intra-operative ICG angiography of

patient 1, a 35-year-old man with primary infertility

and oligoasthenoteratozoospermia. The testicular

artery appeared green on the overlay image mode

with clear simultaneous visualisation of white light

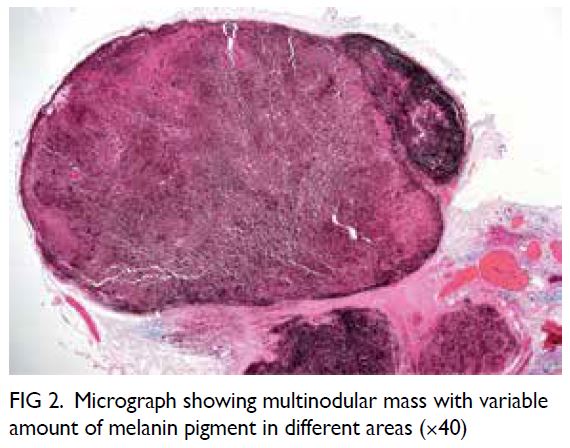

microscopy images in the background (Fig 1a and b).

In addition to the testicular artery, the small

(<1 mm) cremasteric artery could also be identified

in the monochromatic mode that further enhanced

the contrast (Fig 1c). After successful preservation

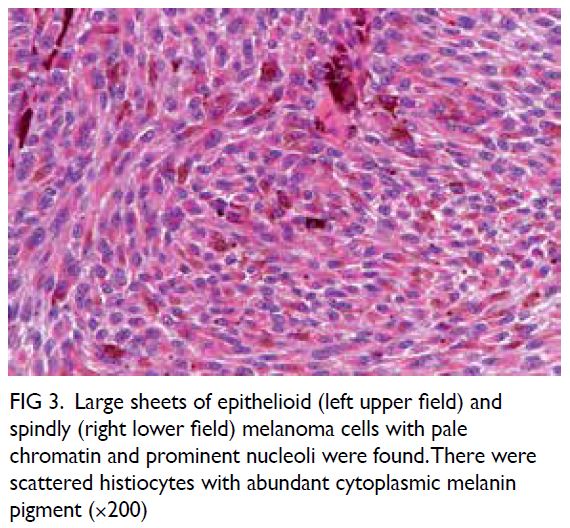

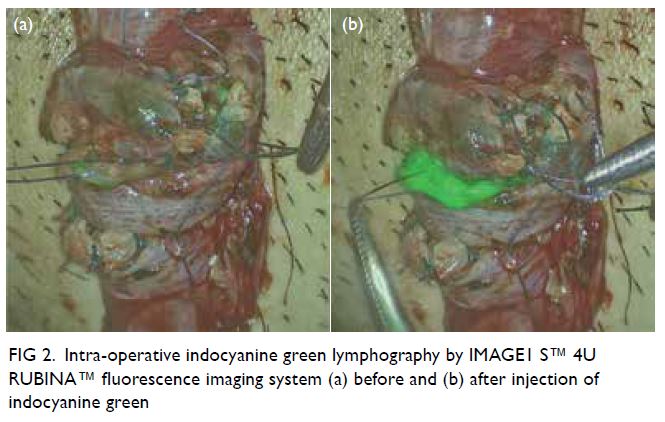

of the testicular arteries in patient 2, a 28-year-old

man with left scrotal pain, two probable lymphatics

were identified under white light microscopy

(Fig 2a). The strong green colouration seen in the

overlay mode after ICG injection unambiguously

confirmed the successful preservation of lymphatics

in MSV (Fig 2b).

Figure 1. Intra-operative indocyanine green angiography by IMAGE1 S™ 4U RUBINA™ fluorescence imaging system. (a) The testicular artery is exposed under the white light microscopic view after retraction of the dilated internal spermatic veins. (b) The testicular artery is confirmed and appears green in the overlay mode with background white light images. (c) The testicular and cremasteric arteries are clearly demonstrated in monochromatic mode. The testicular and cremasteric arteries are denoted by arrows and stars, respectively

Figure 2. Intra-operative indocyanine green lymphography by IMAGE1 S™ 4U RUBINA™ fluorescence imaging system (a) before and (b) after injection of indocyanine green

Microsurgical subinguinal varicocelectomy

is the standard for varicocele repair with excellent

surgical outcomes reported.4 Nonetheless identification of testicular arteries and lymphatics

under white light microscopy alone is operator-dependent

and remains challenging for novice

surgeons. Several adjuncts have been introduced to

facilitate artery- and lymphatic-sparing procedures

during MSV. One such adjunct is ICG fluorescence

imaging.1 In our opinion, the new overlay mode

provided by the latest platform is particularly useful

for MSV. Without the need to switch between

different modes, the combined regular white light

image and near-infrared/ICG data allow accurate

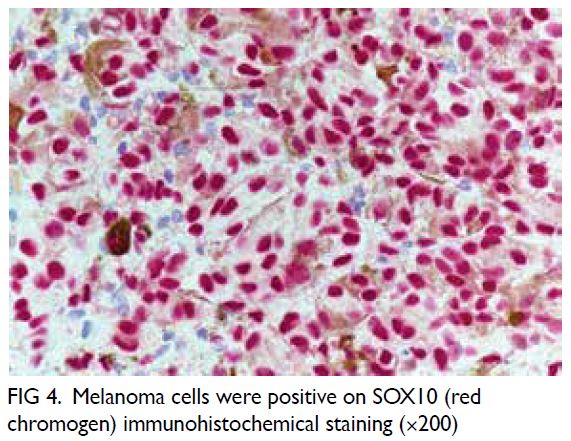

localisation of even the smallest vessel without ambiguity (Fig 3). Moreover, the display of ICG

signal alone in white on a black background in the

monochromatic mode maximises contrast and

further improves identification of target vessels

(Fig 3). We believe the advances of this surgical

platform and imaging technology play a role in

enhancing patient safety by increasing the success of

arterial and lymphatic preservation in MSV.

Figure 3. Intra-operative indocyanine green (ICG) angiography with the previous fluorescence imaging platform utilising VITOM II ICG system with SPIES camera (KARL STORZ SE, Tuttlingen, Germany). Without the overlay mode, the images of (a) white light microscopy view and (b) Chroma mode can only be analysed separately. Correlation between the testicular arteries identified on ICG angiography and white light microscopy can be difficult

Author contributions

Concept or design: CL Cho.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have disclosed no conflict of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

Patients were treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients provided written informed consent for the procedures, and verbal consent for publication.

References

1. Cho CL. Is there any role for indocyanine green

angiography in testicular artery preservation during

microsurgical subinguinal varicocelectomy? In: Esteves

SC, Cho CL, Majzoub A, Agarwal A, editors. Varicocele

and Male Infertility: a Complete Guide. Switzerland AG:

Springer Nature; 2019: 603-14. Crossref

2. Cho CL, Chu RW. Use of video microsurgery platform

in microsurgical subinguinal varicocelectomy with

indocyanine green angiography. Surg Prac 2019;23:20-4. Crossref

3. Cho CL, Chiu PK, Chu RW. Preliminary experience with

indocyanine green lymphography during microsurgical

subinguinal varicocelectomy. Surg Prac 2021;25:207-10. Crossref

4. Zini A. Varicocelectomy: microsurgical subinguinal technique is the treatment of choice. Can Urol Assoc J

2007;1:273-6.

A video clip demonstrating systematic transperineal prostate biopsy is avaialble at

A video clip demonstrating systematic transperineal prostate biopsy is avaialble at