A curious case of small vessel vascular dementia

Hong Kong Med J 2023 Apr;29(2):174.e1–3

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PICTORIAL MEDICINE

A curious case of small vessel vascular dementia

Whitney CT Ip, MRCP (UK)1; YF Shea, FHKAM (Medicine)1; HF Tong, FHKCPath2,3; CY Law, FHKAM (Pathology)2; CW Lam, FHKAM (Pathology)2,4; Patrick KC Chiu, FHKAM (Medicine)1

1 Department of Medicine, Queen Mary Hospital, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Division of Chemical Pathology, Department of Pathology, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Department of Pathology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

4 Department of Pathology, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr YF Shea (syf321@ha.org.hk)

A 63-year-old man was referred to the memory

clinic of Queen Mary Hospital in December 2021 for

early-onset dementia. He had stepwise deterioration

in cognitive function over the previous 6 months,

especially in short-term memory, poor judgement,

and spatial and temporal disorientation. His home

environment was poor with rotten food. Physical

examination revealed symmetrical parkinsonism.

Montreal Cognitive Assessment Hong Kong version

score was 10/30 (<2nd percentile). Vitamin B12,

folate and thyroid function tests were normal.

A review of his medical history revealed three

episodes of stroke since the age of 50 years. These

episodes presented as left lower limb monoplegia,

left-sided hemiplegia and slurring of speech 12

years, 8 years, and 1 year ago, respectively. Extensive

workup including 24-hour Holter monitoring and

transthoracic echocardiogram was unremarkable.

He had hypertension and hyperlipidaemia and was

prescribed amlodipine 5 mg and rosuvastatin 20 mg

daily. His blood pressure was under control and the

latest low-density lipoprotein was 1.7 mmol/L. A

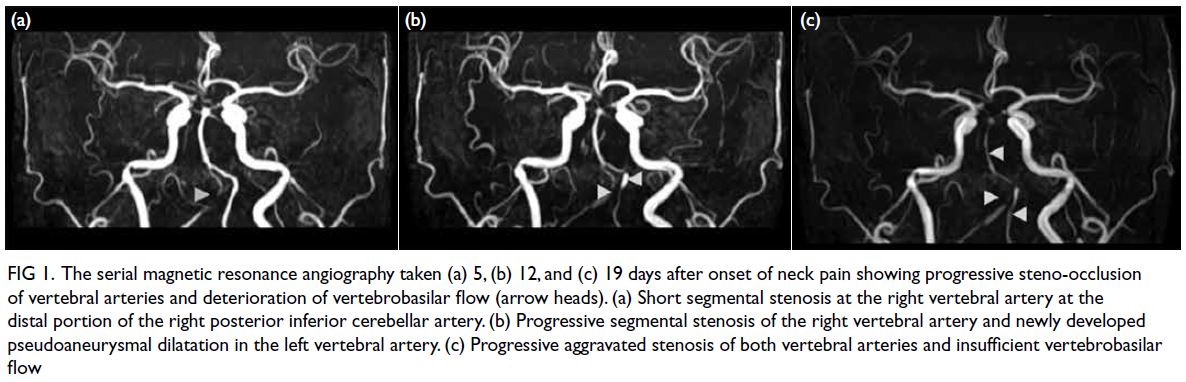

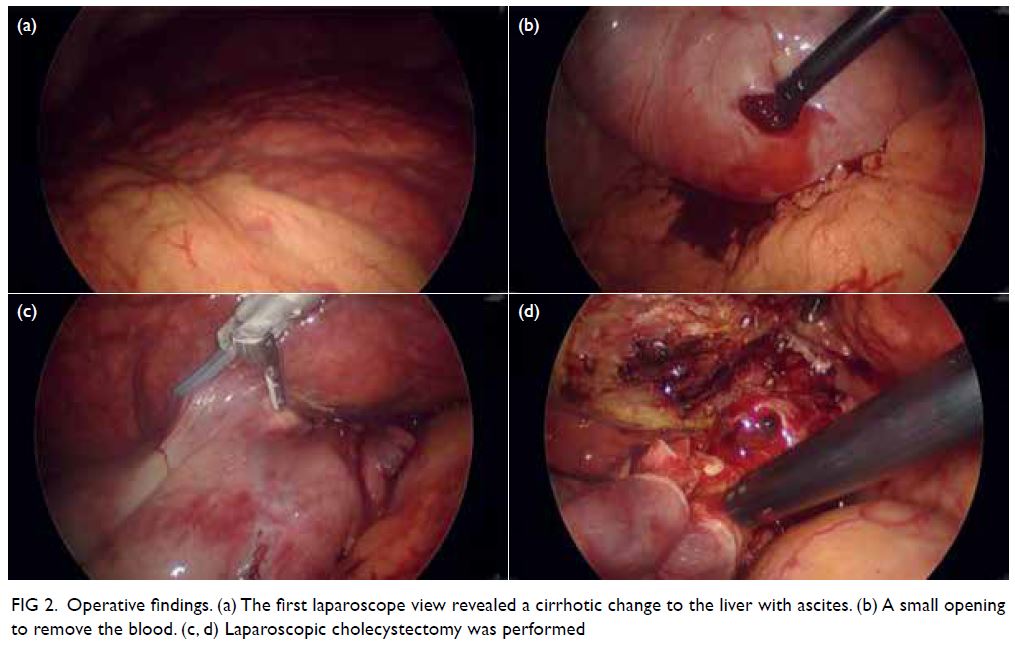

review of his computed tomography of the brain over the last 11 years showed a progressive increase in

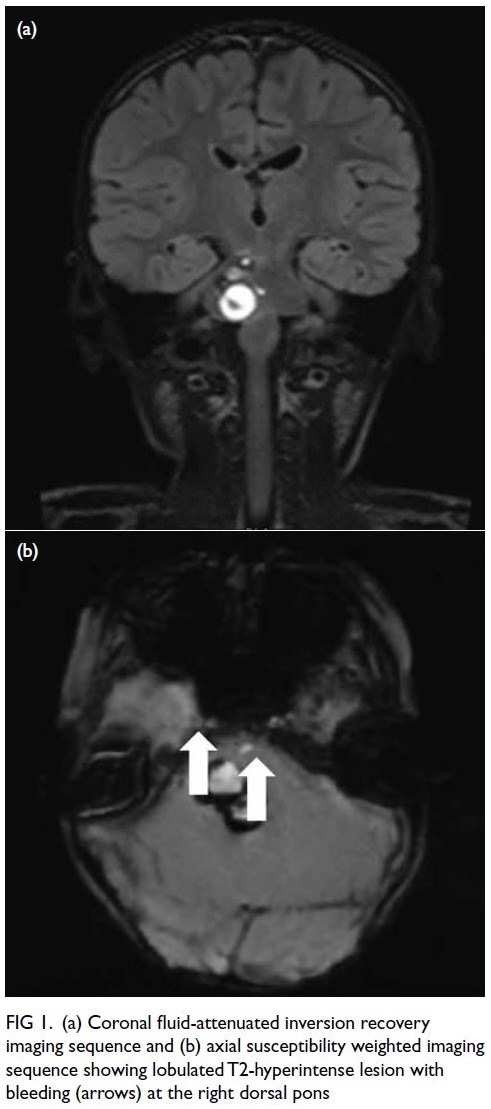

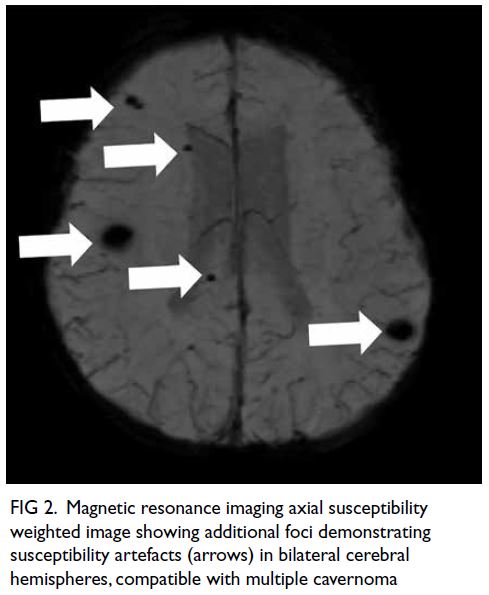

periventricular hypodensities (Fig 1). Brain magnetic

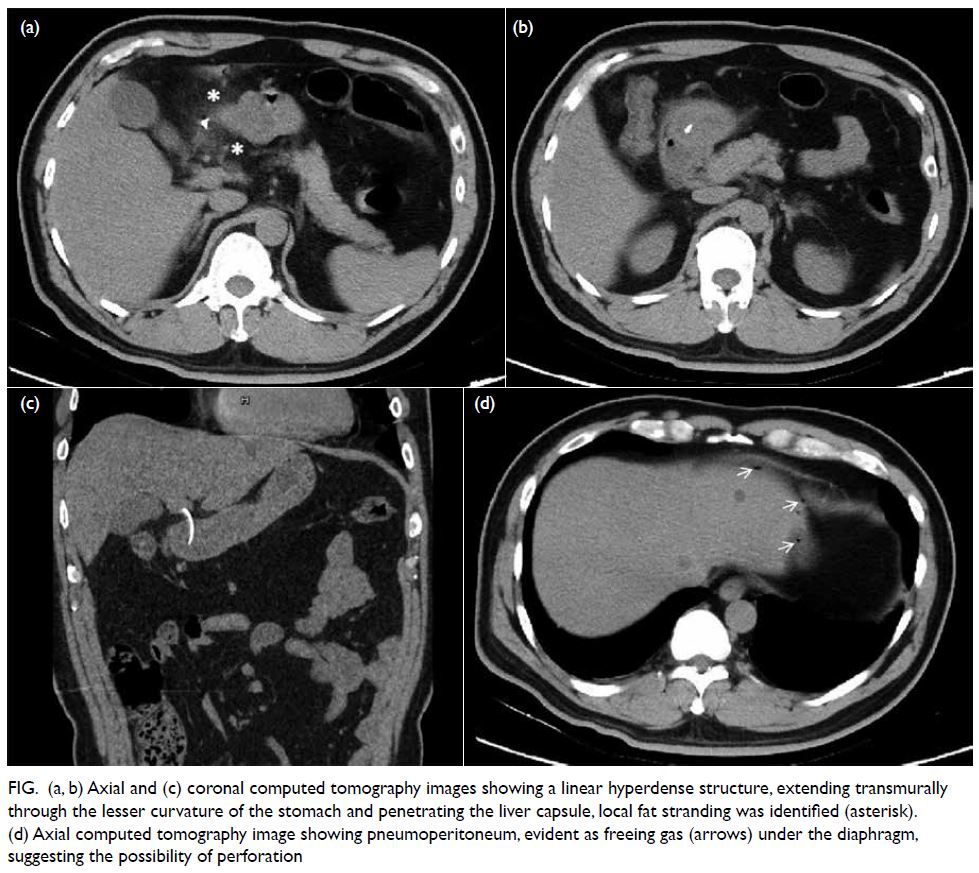

resonance imaging (1 year previously) showed

extensive periventricular hyperintensities and an

old ischaemic insult over bilateral external capsules

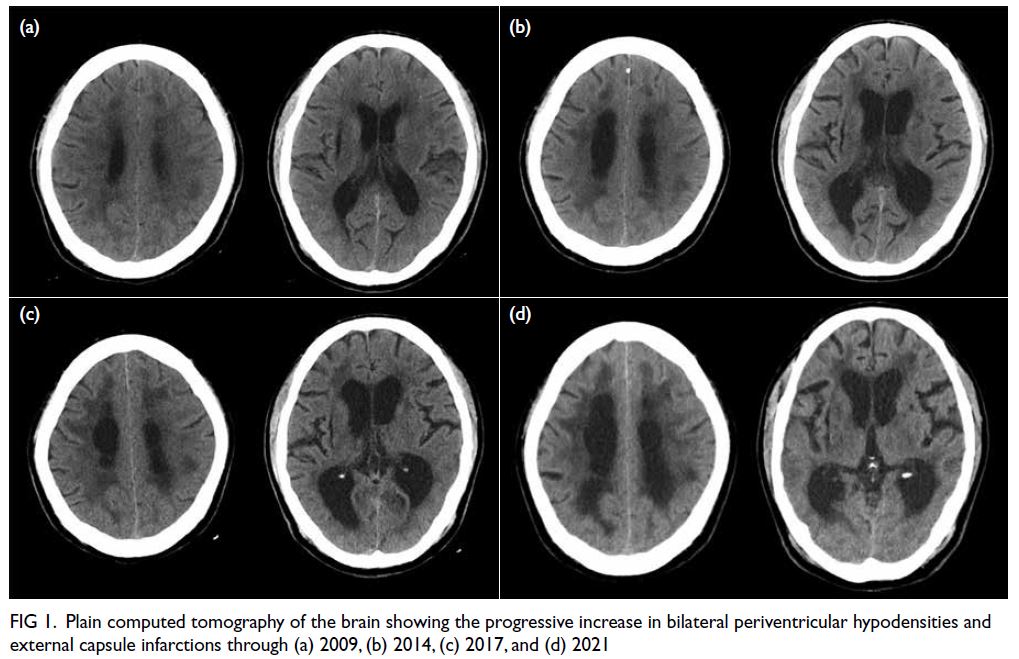

(Fig 2). Family history was notable for multiple

first-degree relatives with young-onset stroke in

their fifties and a suspected autosomal dominant

inheritance pattern (Fig 3). Genetic testing of

the neurogenic locus notch homolog protein 3

(NOTCH3) gene revealed a heterozygous mutation

with a pathogenic variant (c.1630C>T, p.Arg544Cys),

confirming the diagnosis of cerebral autosomal

dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and

leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL). The family was

referred for genetic counselling.

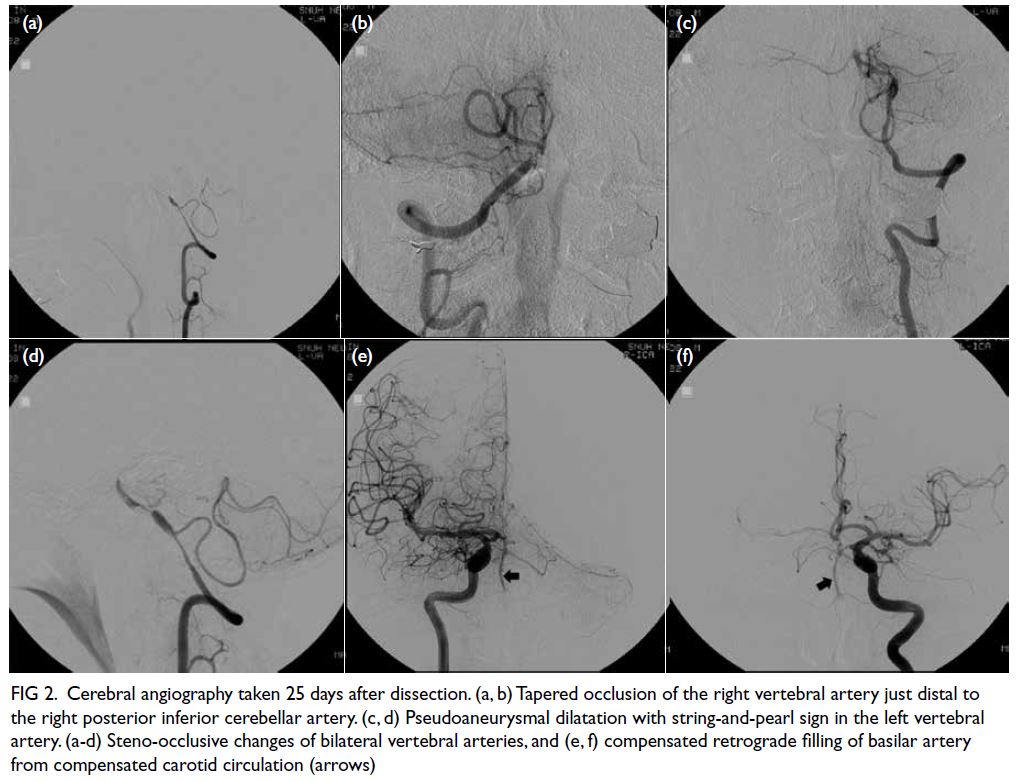

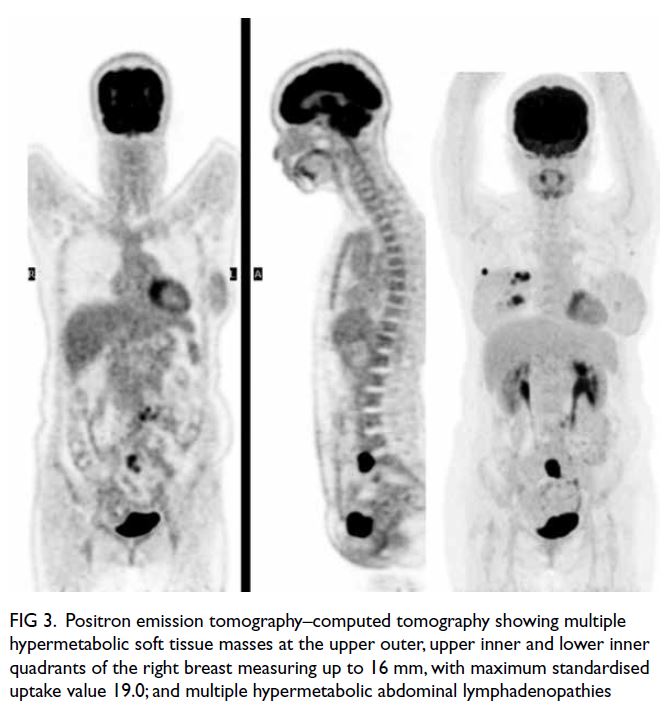

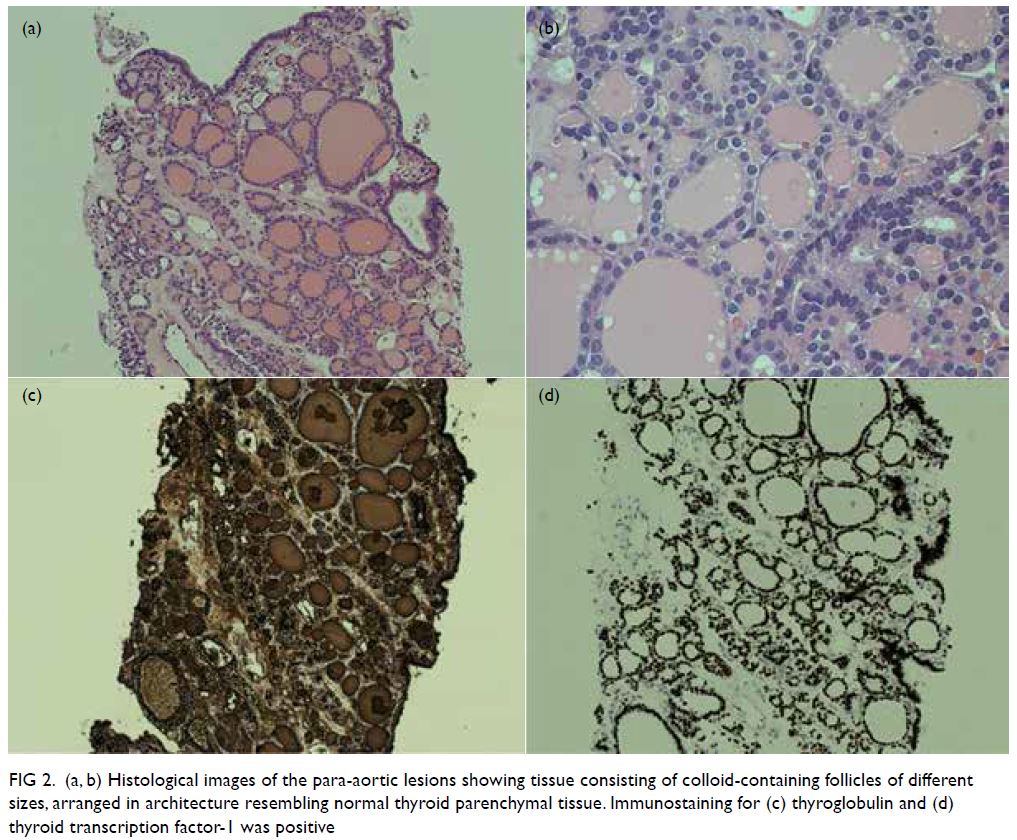

Figure 1. Plain computed tomography of the brain showing the progressive increase in bilateral periventricular hypodensities and external capsule infarctions through (a) 2009, (b) 2014, (c) 2017, and (d) 2021

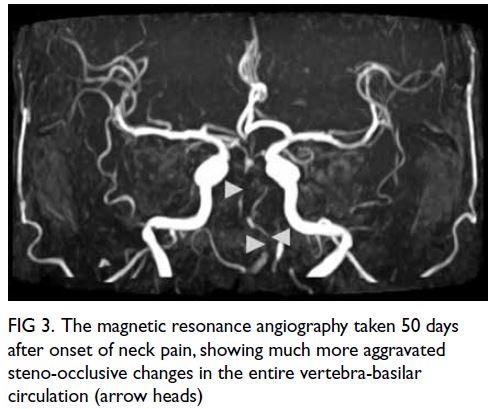

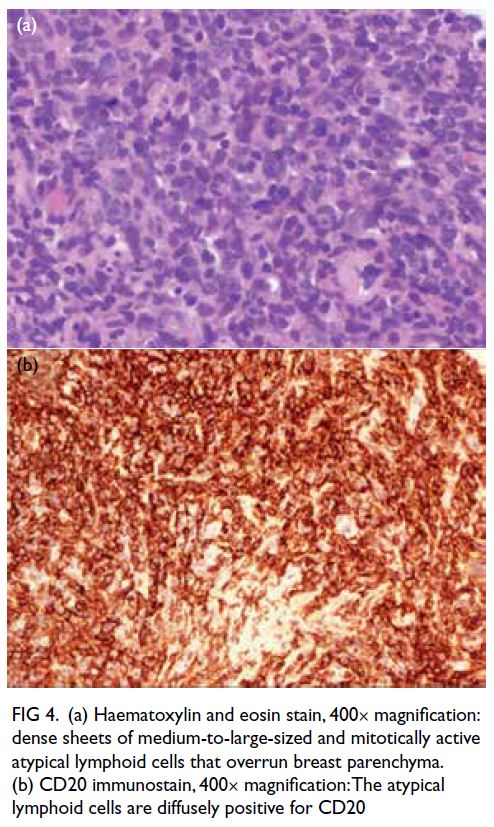

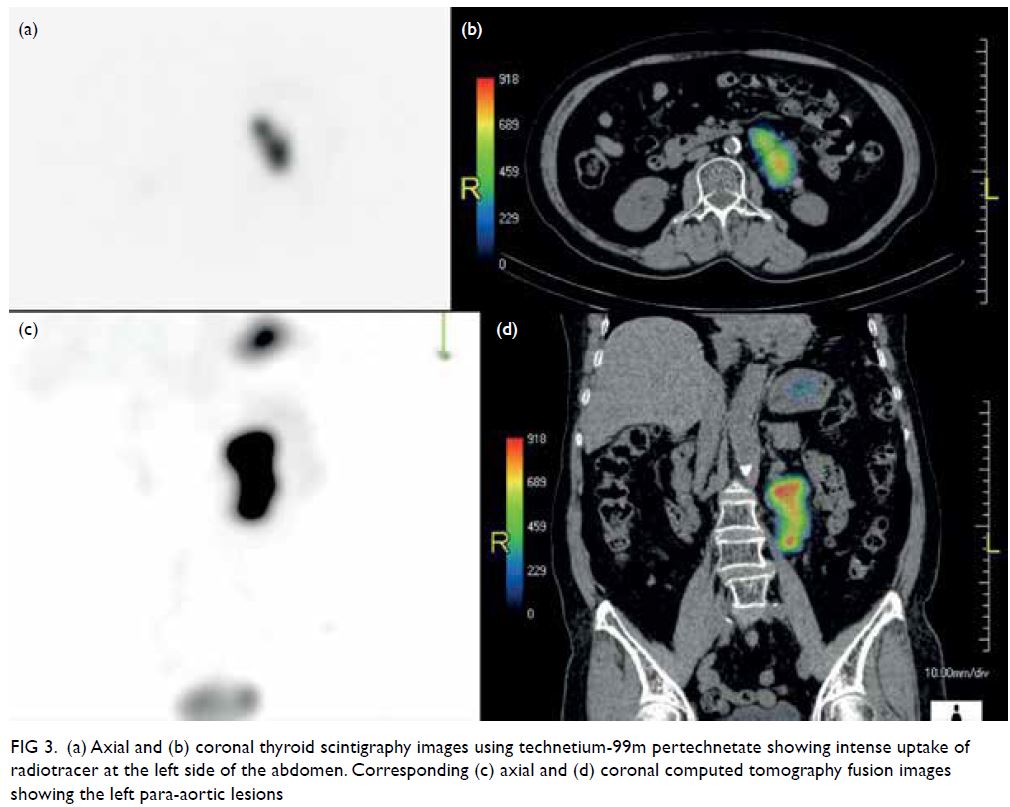

Figure 2. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed extensive white matter abnormalities compatible with cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL). (a) Coronal fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequence MRI showing periventricular hyperintensities. Temporal lobes had focal subcortical white matter hyperintensities, which are common findings in CADASIL. (b) Axial T2-weighted MRI showing extensive white matter hyperintensities. (c) Axial T2-weighted MRI showing the infarcts located at bilateral basal ganglia and external capsules. (d) T2 gradient echo sequence showed hemosiderin deposition over the bilateral external capsules suggestive of previous haemorrhage over the infarcted areas

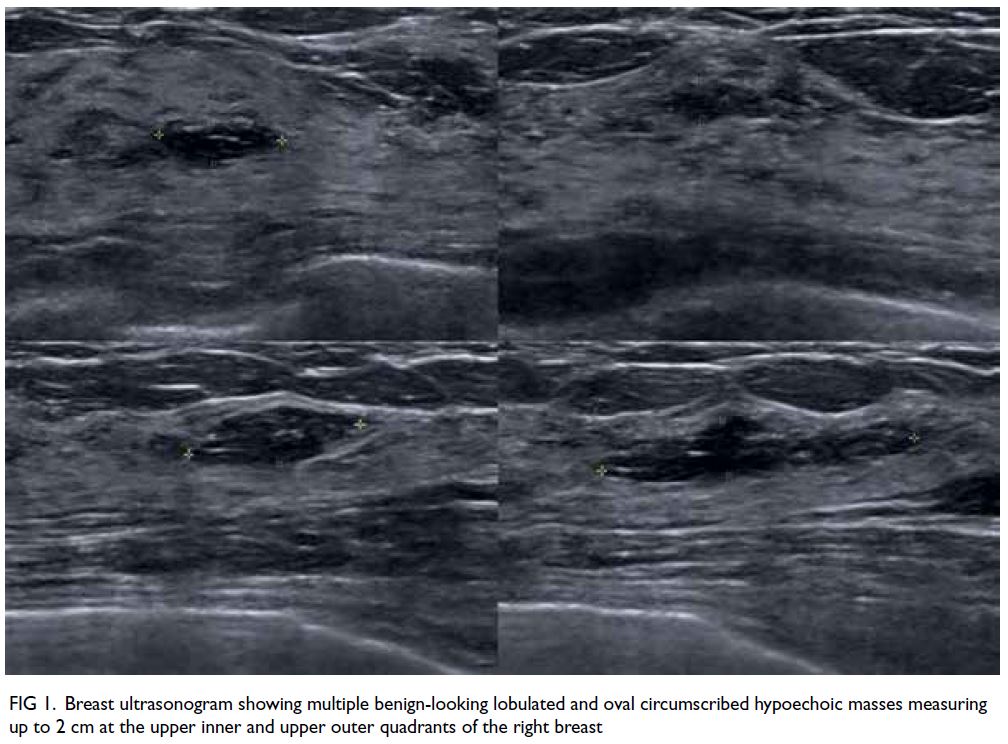

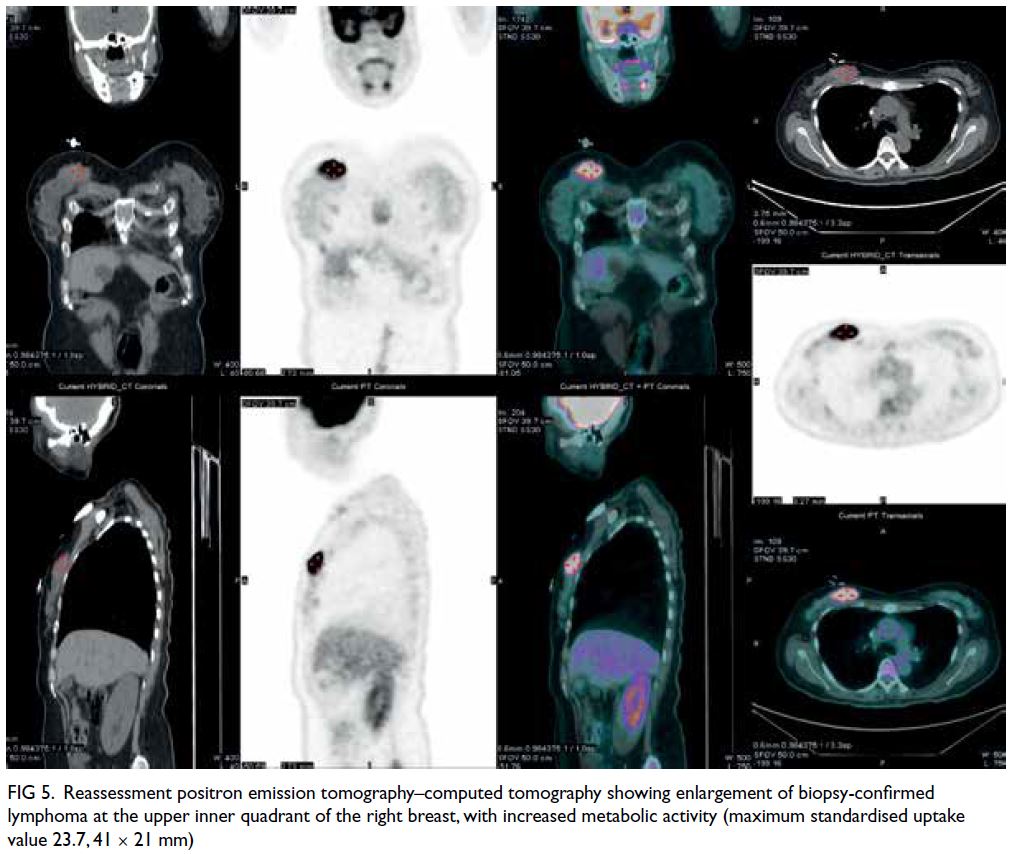

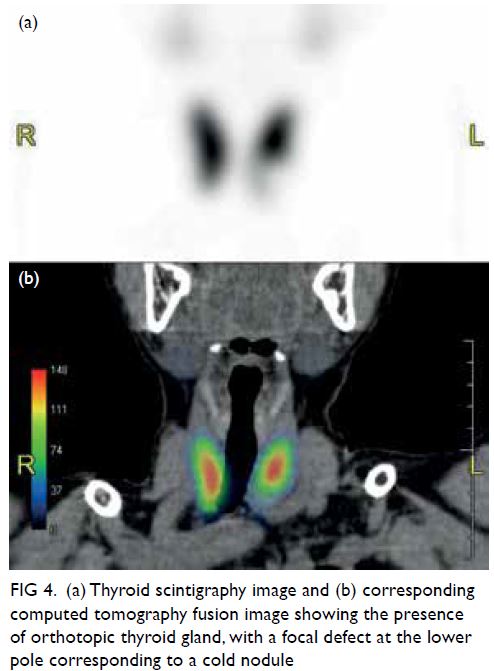

Figure 3. Pedigree of the patient’s family showing the autosomal dominant inheritance pattern of disease transmission

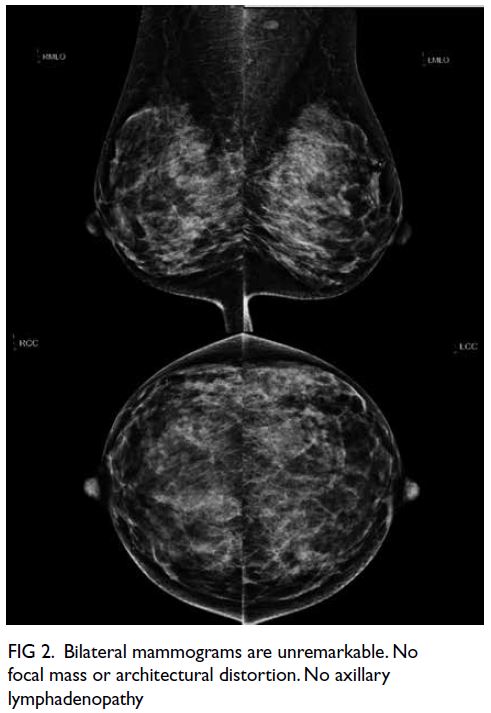

Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy

with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy

is caused by cysteine-altering pathogenic variants in

the NOTCH3 gene, with consequent vasculopathic

changes, predominantly involving small penetrating

arteries, arterioles, and brain capillaries.1 2 The

mutation leads to an odd number of cysteine residues with deposition of osmiophilic material

and progressive degeneration of vascular smooth

muscle cells.1 2 The key to diagnosis includes a strong

family history of young-onset stroke, an absence

of strong vascular risk factors, and salient findings on brain magnetic resonance imaging, especially

extensive white matter abnormalities and subcortical

infarcts involving external capsules. Genetic testing

for the NOTCH3 gene can be arranged after

consultation with chemical pathologists in major public hospitals.3 4 The principle of management

for symptomatic patients is similar to that of other

patients with stroke, ie, antiplatelet therapy, lipid-lowering

agents, and blood pressure control. There

is no disease-modifying therapy currently available.

Family members of affected individuals should

be referred for genetic counselling with referral

to tertiary centres for potential pre-implantation

genetic testing to avoid transferring the mutation

to offspring.5 There have been four other reported

families with CADASIL in Hong Kong with different

mutations. The mean age of symptom onset for

index patients of these families was 51 years.3 4 The

mutation in our patient has been commonly found

in Fujian province and Taiwan, accounting for up to

14.5% to 70% of CADASIL cases.1

In summary, clinicians should obtain a

detailed history and be alert to suspicious magnetic

resonance imaging findings. Referral to chemical

pathologists for genetic testing is key to the diagnosis

of CADASIL.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept or design of the study, acquisition of the data, analysis or interpretation of the

data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the

manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors

had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved

the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its

accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Patient consent was obtained for all investigations.

References

1. Chen S, Ni W, Yin XZ, et al. Clinical features and mutation spectrum in Chinese patients with CADASIL: a multicenter retrospective study. CNS Neurosci Ther 2017;23:707-16. Crossref

2. Hu Y, Sun Q, Zhou Y, et al. NOTCH3 variants and genotype-phenotype features in Chinese CADASIL patients. Front Genet 2021;12:705284. Crossref

3. Au KM, Li HL, Sheng B, et al. A novel mutation (C271F) in the Notch3 gene in a Chinese man with cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. Clin Chim Acta 2007;376:229-32. Crossref

4. Hung LY, Ling TK, Lau NK, et al. Genetic diagnosis of CADASIL in three Hong Kong Chinese patients: a novel mutation within the intracellular domain of NOTCH3. J Clin Neurosci 2018;56:95-100. Crossref

5. Konialis C, Hagnefelt B, Kokkali G, Pantos C, Pangalos C. Pregnancy following pre-implantation genetic diagnosis of cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL). Prenat Diagn 2007;27:1079-83. Crossref

A video clip demonstrating physical examination findings of bilateral fixed left lateral gaze and right lower-motor-neuron seventh cranial nerve palsy is available at

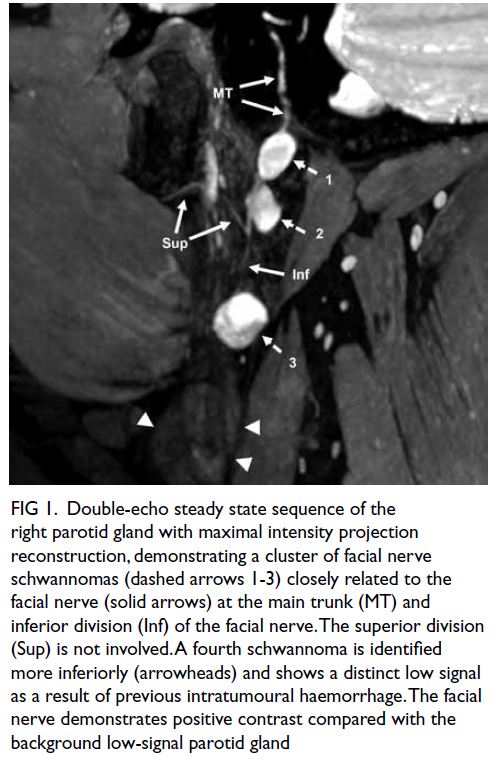

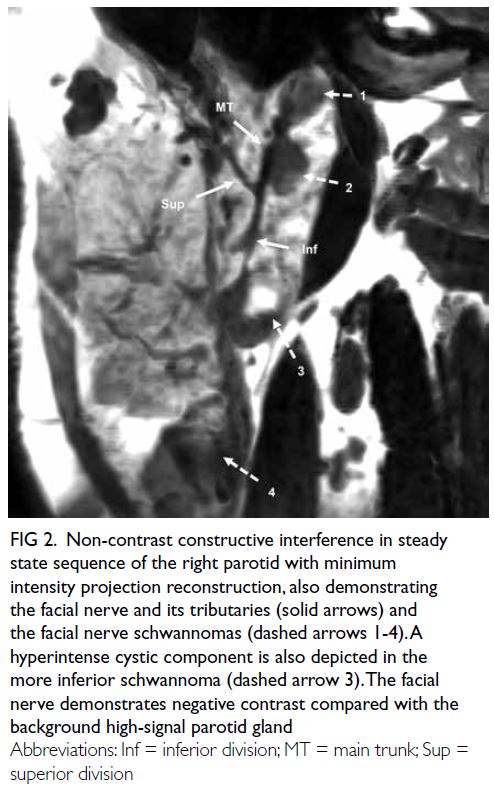

A video clip demonstrating physical examination findings of bilateral fixed left lateral gaze and right lower-motor-neuron seventh cranial nerve palsy is available at