Hong

Kong Med J 2021 Feb;27(1):58–9.e1–2

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PICTORIAL MEDICINE

Popliteal artery entrapment syndrome: a rare

diagnosis for calf pain

Stephanie C Woo, MB, BS, FRCR; TS Chan, FHKCR, FHKAM (Radiology); NY Pan, FHKCR, FHKAM (Radiology); Johnny KF Ma, FRCR (UK), FHKAM (Radiology)

Department of Radiology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr SC Woo (stephaniecheriwoo@gmail.com)

An 18-year-old man presented with a long history

of occasional right calf pain and fullness. He also

complained that over the last year his right foot

An 18-year-old man presented with a long history

of occasional right calf pain and fullness. He also

complained that over the last year his right foot became pale and numb after exercising for few

minutes. There was no history of trauma and the

patient had no constitutional symptoms. On physical

examination, the right calf was non-tender with no

mass although right posterior tibial and dorsalis

pedis pulses were weaker than the left. Radiograph

of the right knee showed static right proximal

tibial exostosis, which had been monitored since

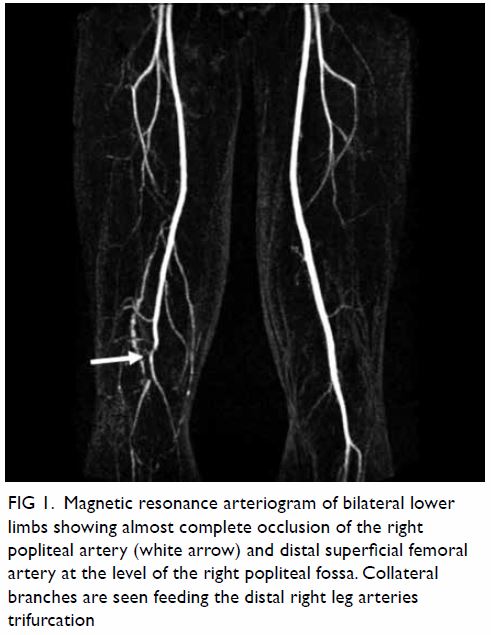

the patient was aged 10 years. Magnetic resonance

arteriogram showed almost complete occlusion

of the right popliteal artery and distal superficial

femoral artery at the level of the right popliteal

fossa (Fig 1). Collateral branches were seen feeding

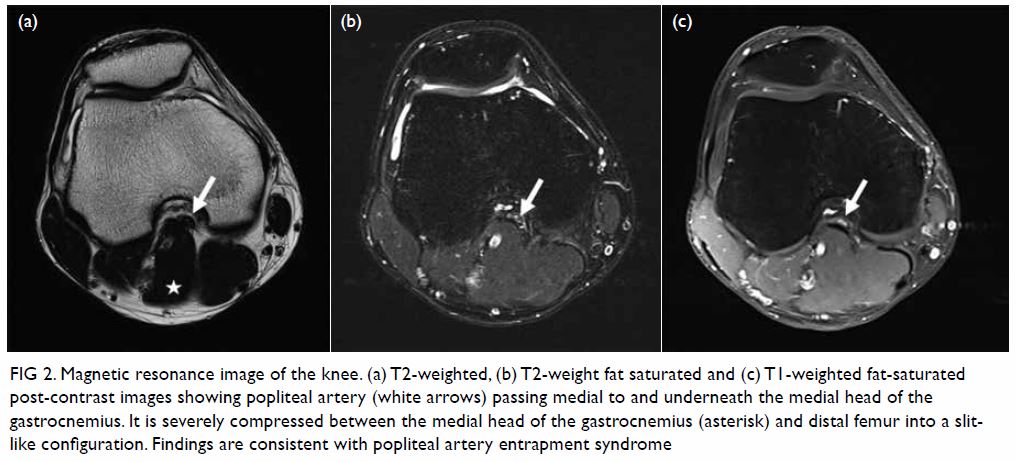

the distal right leg arteries trifurcation. Magnetic

resonance imaging scan of the knee revealed the

medial head of the gastrocnemius inserting at a

more lateral position than usual (Fig 2). The popliteal

artery was separated from the popliteal vein, passing

medial to and underneath the medial head of

the gastrocnemius, and was severely compressed

between the medial head of the gastrocnemius and

distal femur. Loss of normal flow-related signal void

was noted in the right popliteal artery distal to the

compression.

Figure 1. Magnetic resonance arteriogram of bilateral lower limbs showing almost complete occlusion of the right popliteal artery (white arrow) and distal superficial femoral artery at the level of the right popliteal fossa. Collateral branches are seen feeding the distal right leg arteries trifurcation

Figure 2. Magnetic resonance image of the knee. (a) T2-weighted, (b) T2-weight fat saturated and (c) T1-weighted fat-saturated post-contrast images showing popliteal artery (white arrows) passing medial to and underneath the medial head of the gastrocnemius. It is severely compressed between the medial head of the gastrocnemius (asterisk) and distal femur into a slitlike configuration. Findings are consistent with popliteal artery entrapment syndrome

Popliteal artery entrapment syndrome (PAES)

is a rare1 and frequently underdiagnosed disease

entity. It typically affects young male athletes who

commonly have hypertrophied musculature without

significant cardiovascular risk factors. The classic presentation of PAES is of symptoms related to

vascular compression, which is intermittent lower

limb claudication. Other symptoms can include

numbness, pain, discoloration, or even paralysis.2

Symptoms in the early stages typically occur during

or following physical activity but can progress to

symptoms at rest if complications develop.

In addition to a careful history, proper physical

examination aids in diagnosis. Usual findings include

calf muscle hypertrophy,2 and reduced posterior tibial

and dorsalis pedis pulses on passive dorsiflexion or

active plantar flexion of the foot.3 In addition, resting

ankle-brachial index tests will usually be normal

but will show a decrease with exercise.4 Differential

diagnoses include other vascular diseases such as

atherosclerosis, exertional syndrome, and cystic

adventitial disease. Further diagnostic testing is

usually needed to make a confident diagnosis of PAES.

Doppler ultrasonography is one of the first-line

imaging modalities. It may demonstrate popliteal

artery stenosis, increased velocity, or reduced peak

systolic velocity during stress manoeuvres. However,

it plays a limited role since imaging findings with

this modality are non-specific and show only the

consequences of the abnormal anatomy.4

Conventional angiography has been long used

for the diagnosis of PAES.1 Typical findings include

medial deviation of the proximal segment, occlusion

in the middle segment, and post-stenotic dilatation

at the distal segment.5 However, it is invasive and

is unable to demonstrate surrounding soft tissue

structures leading to the occlusion of the popliteal

artery. It has recently been replaced by diagnostic

modalities that are non-invasive such as computed

tomography angiography and magnetic resonance

imaging with magnetic resonance arteriogram.

Computed tomography angiography offers

good soft tissue contrast and can provide diagnostic

evaluation of surrounding muscular anomalies.4 It

may also be used to evaluate the contralateral limb

to exclude bilateral entrapment.

Magnetic resonance imaging and MR

angiography are promising imaging modalities

for the diagnosis of PAES6 due to their superior

capability to demonstrate surrounding anatomy and

soft tissue compared with computed tomography

angiography, with no ionising radiation required.

In this case, timely diagnosis was made and

treatment given. However, delay in diagnosis and

management may lead to irreversible effects of lower

limb ischaemia. This case illustrates the importance

of considering this rare diagnosis when encountering young patients with lower limb claudication or calf

pain symptoms. This will facilitate early surgical

intervention to minimise the risk of complications.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the design, acquisition of data, analysis of data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical

revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This pictorial medicine received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit

sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient provided written informed consent for

the treatment/procedures, and consent for publication.

References

1. Thanila AM, Johnson CM, Hallett JW Jr, Breen JF. Popliteal artery entrapment syndrome: role of imaging in

the diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003;181:1259-65. Crossref

2. Davis DD, Shaw PM. Popliteal Artery Entrapment

Syndrome. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island

(FL): StatPearls Publishing; 10 May 2019. Available from:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441965/.

Accessed 1 Apr 2020.

3. Tercan F, Oğuzkurt L, Kizilkiliç O, Yeniocak A, Gülcan O. Popliteal artery entrapment syndrome. Diagn Interv

Radiol 2005;11:222-4.

4. Eliahou R, Sosna J, Bloom AI. Between a rock and a hard place: clinical and imaging features of vascular

compression syndromes. Radiographics 2012;32:33-49. Crossref

5. Zhong H, Liu C, Shao G. Computed tomographic

angiography and digital subtraction angiography findings

in popliteal artery entrapment syndrome. J Comput Assist

Tomogr 2010;34:254-9. Crossref

6. Atilla S, Ilgit ET, Akpek S, Yücel C, Tali ET, Işik S. MR imaging and MR angiography in popliteal artery

entrapment syndrome. Eur Radiol 1998;8:1025-9. Crossref