Hong

Kong Med J 2021 Jun;27(3):223.e1–2

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PICTORIAL MEDICINE

Primary orbital melanoma

Vivian WK Hui, MB, ChB1; TC Lau, PhD2; Lawrence PW Ng, MSc2; Hunter KL Yuen, FRCOphth1; W Cheuk, FHKCPath2

1 Department of Ophthalmology, Hong Kong Eye Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Department of Pathology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr W Cheuk (cwzz01@ha.org.hk)

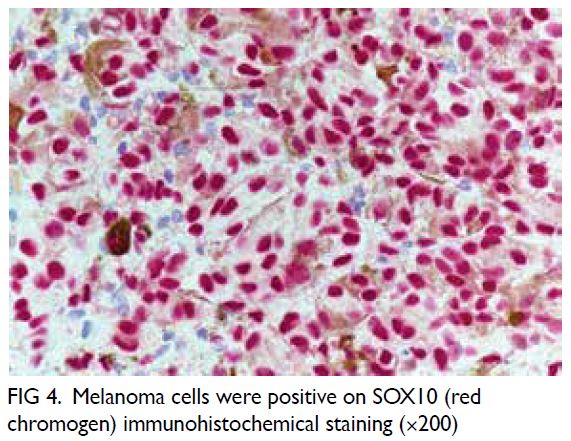

A 68-year-old Chinese man presented with proptosis,

epiphora and discomfort in the right eye associated

with impaired visual acuity. Contrast computed

tomography scan revealed a 3.3 cm × 2.1 cm

heterogeneously enhancing mass at the

superotemporal aspect of the right orbit with

displacement of the lateral rectus muscle (Fig 1).

A pigmented tumour with dense adhesions to the

surrounding structures was found in orbitotomy

with leakage of the pigmented content upon surgical

exploration. The lesion was excised as much as

possible. Detailed clinical examination showed no

evidence of intraocular melanoma, conjunctival

or eyelid melanoma, or melanoma anywhere else.

Systemic examination and whole-body positron

emission tomography-computed tomography scan

were unremarkable. The patient was alive with no

evidence of disease at 9-month follow-up.

Figure 1. Contrast computed tomography scan showing a contrast-enhancing tumour behind the right globe displacing the optic nerve

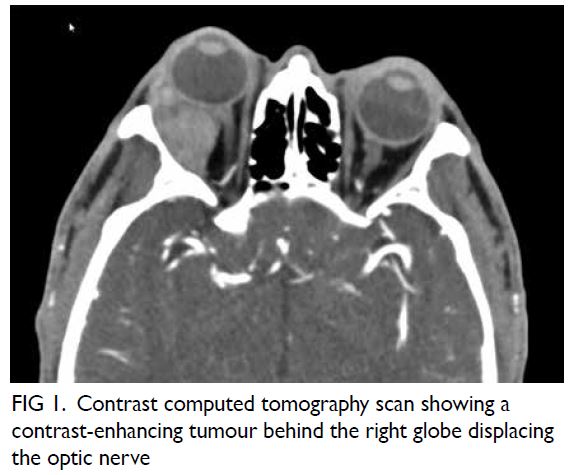

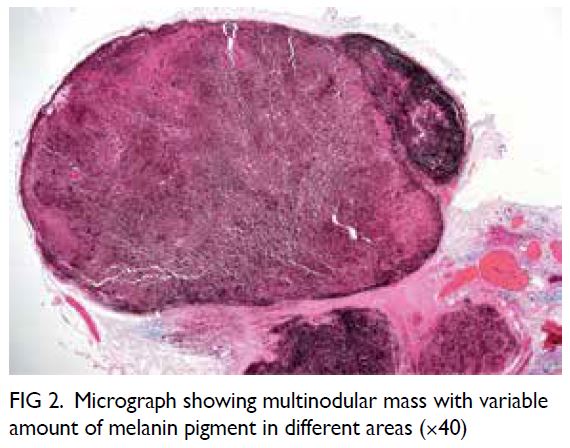

The tumour was a solid, dark brownish

multinodular mass covered by fat and skeletal

muscle, comprising lobulated sheets of epithelioid

and spindly melanocytes with vesicular chromatin,

prominent nucleoli, and variable amounts of

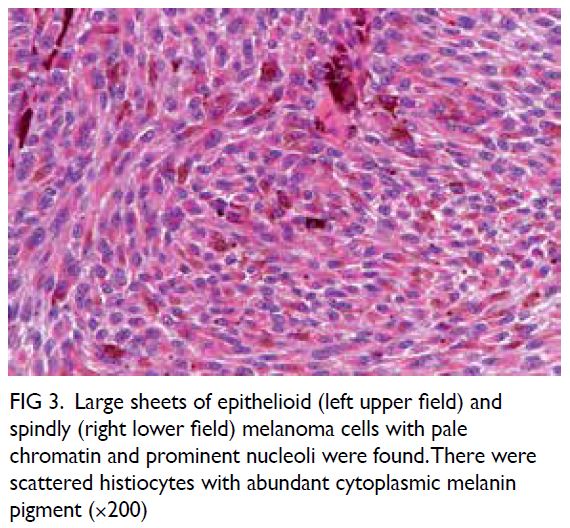

melanin pigment (Figs 2, 3, and 4). The mitotic count

was 1 per 10 HPFs. The neoplastic melanocytes were

positive for S100 and SOX10 but negative for BRAF.

BRCA1-associated protein 1 immunostaining was

intact. Sanger sequencing revealed a GNA11 Q209L

mutation. No mutation was found in GNAQ, NRAS,

KRAS, BRAF or KIT.

Figure 2. Micrograph showing multinodular mass with variable amount of melanin pigment in different areas (×40)

Figure 3. Large sheets of epithelioid (left upper field) and spindly (right lower field) melanoma cells with pale chromatin and prominent nucleoli were found. There were scattered histiocytes with abundant cytoplasmic melanin pigment (×200)

Ocular melanoma most frequently involves

the uveal tract (choroid, ciliary body, and iris) and

the conjunctiva, where melanocytes are normally present. According to The Cancer Genome Atlas

uveal melanoma project, mutually exclusive

mutations in GNAQ, GNA11, CYSLTR2 and PLCB4

are the tumour-initiating mutations whereas BAP1,

EIF1AX and SF3B1/SRSF2 mutations are associated

with prognosis in uveal melanoma.1 In contrast,

conjunctival melanoma typically exhibits BRAF,

NRAS and NF1 mutations of the MAPK pathway

with UV-induced C→T mutation signature.2

Orbital soft tissue melanoma is uncommon with

>90% representing secondary tumours as a result

of contiguous spread or metastasis from uveal,

conjunctival, cutaneous or sinonasal melanomas.3

Primary orbital melanoma is exceedingly rare

and has been postulated to arise in embryological

remnants of melanocytes arrested in the region since

a substantial proportion of cases are associated with

blue nevus, orbital melanocytosis or oculodermal

melanocytosis (nevus of Ota). Alternatively, it may

arise from isolated melanocytes found in the optic

nerve sheath, orbital fat, extraocular muscles or

orbital periosteum. The majority of patients are

white Europeans in their fourth to fifth decade.

Histologically, it comprises epithelioid, spindle or

mixed populations of neoplastic melanocytes that

are frequently pigmented but with a lesser degree

of nuclear pleomorphism than their cutaneous and

mucosal counterparts. The prognosis is generally

poor but a small proportion of patients survive

long term. The most frequent site of metastasis

is the liver.3 4 The clinicopathological features of

primary orbital melanoma are very similar to those

of uveal melanoma. The findings of GNAQ, SF3B1,

EIF1AX mutations5 and GNA11 mutation in this

case provide further evidence that primary orbital

melanoma has a close pathogenic relationship with

uveal melanoma.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept or design of the study, acquisition of the data, analysis or interpretation of the

data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the

manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors

had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved

the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its

accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an adviser of the journal, HKL Yuen was not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no

conflicts of interest.

Declaration

This case was presented as a poster at the Annual Scientific Meeting of The College of Ophthalmologists of Hong Kong

and Hong Kong Ophthalmological Society on 14 to 15

December 2019.

Funding/support

This pictorial medicine paper received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-forprofit

sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from

the patient.

References

1. Bakhoum MF, Esmaeli B. Molecular characteristics of uveal melanoma: insights from the Cancer Genome Atlas

(TCGA) Project. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:1061.Crossref

2. Swaminathan SS, Field MG, Sant D, et al. molecular characteristics of conjunctival melanoma using whole-exome

sequencing. JAMA Ophthalmol 2017;135:1434-7. Crossref

3. Rose AM, Luthert PJ, Jayasena CN, Verity DH, Rose GE. Primary orbital melanoma: presentation, treatment,

and long-term outcomes for 13 patients. Front Oncol

2017;7:316. Crossref

4. Shields JA, Shields CL. Orbital malignant melanoma: the 2002 Sean B Murphy lecture. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr

Surg 2003;19:262-9. Crossref

5. Rose AM, Luo R, Radia UK, et al. Detection of mutations in SF3B1, EIF1AX and GNAQ in primary orbital melanoma

by candidate gene analysis. BMC Cancer 2018;18:1262. Crossref