Hong

Kong Med J 2021 Jun;27(3):222.e1–2

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PICTORIAL MEDICINE

Tattoo-associated uveitis

CY Mak, MB, BS, MRCSEd (Ophth)1; Mary Ho, FCOphth HK, FHKAM (Ophthalmology)1; Angela Z Chan, MB, BS2; Lawrence PL Iu, FRCSEd (Ophth), FHKAM (Ophthalmology)1; Christina MT Cheung, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)3; Marten E Brelen, BMBCh (Oxon), FRCOphth1; Paul CL Choi, FRCPA, FHKAM (Pathology)2; Alvin L Young, FRCOphth, FHKAM (Ophthalmology)1

1 Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Department of Anatomical and Cellular Pathology, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong

3 Division of Dermatology, Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof Alvin L Young (youngla@ha.org.hk)

A 19-year-old man with extensive body tattooing

presented with recurrent episodes of reduced vision,

bilateral photophobia and concomitant swelling of

body tattoos. He had multiple tattoos over his entire

body with mainly black pigment and occasional red

and yellow pigment, performed over a period of 3

years prior to the presentation of ocular symptoms.

He enjoyed good past health with no history of

autoimmune diseases. There was no joint pain, skin

rash or chest symptoms.

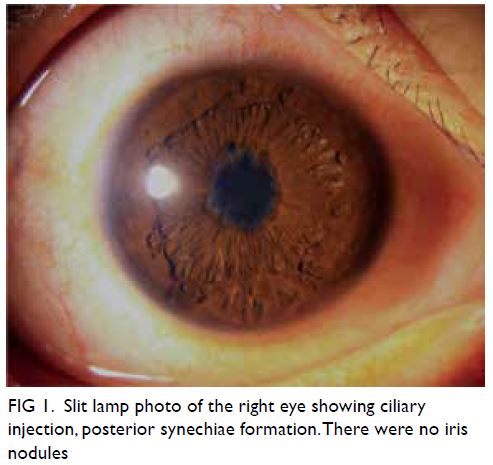

Ophthalmological examination revealed

bilateral injection, anterior chamber cells, posterior

synechiae (Fig 1) and marked vitritis, consistent

with anterior and intermediate uveitis. There were

no mutton-fat keratic precipitates or iris nodules.

Presenting visual acuity was 20/200 in both eyes.

Dermatological examination showed prominent

induration of skin with mild tenderness in areas

of body tattoo containing black pigment (Fig 2).

Non-tattooed skin was unremarkable with no signs

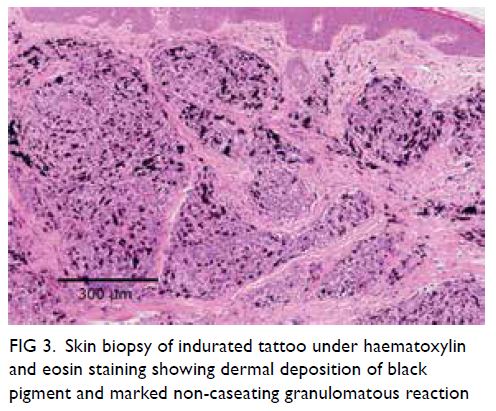

of inflammation. Incisional skin biopsy was taken

from an area of prominently indurated tattoo.

Histopathology showed marked non-caseating

granulomatous reaction within the dermis and

abundant black pigment deposition (Fig 3). Periodic

acid-Schiff staining showed no fungal elements. Chest

radiograph was clear with no hilar lymphadenopathy

and interferon-gamma releasing assay was negative.

Syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus serology

was negative. Immune markers including antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies

and anti-extractable nuclear antigens antibody

were negative. The patient declined a blood test for

angiotensin-converting enzyme level due to the

associated cost. Serum calcium was not elevated.

Figure 1. Slit lamp photo of the right eye showing ciliary injection, posterior synechiae formation. There were no iris nodules

Figure 2. Prominent induration of part of a tattoo containing black pigment. Surrounding non-tattooed skin was unremarkable

Figure 3. Skin biopsy of indurated tattoo under haematoxylin and eosin staining showing dermal deposition of black pigment and marked non-caseating granulomatous reaction

He was treated with topical prednisolone and

oral prednisolone 60 mg daily after exclusion of

infectious uveitides. Body tattoo swelling subsided

rapidly after systemic steroid and the uveitis was

brought under control gradually with significant improvement in bilateral vision. He was maintained

on mycophenolate mofetil 1g twice a day as a steroid-sparing

agent for uveitis control. His oral prednisolone

was tapered to below 15 mg daily. His visual acuity

improved and maintained at 20/30 bilaterally. There

were no features of systemic sarcoidosis. Overall

clinicopathological features were compatible

with tattoo-associated uveitis, a rare dermato-ophthalmological

complication of body tattooing.

Systemic sarcoidosis, a rare disease in Asians,

can occasionally cause tattoo granuloma and

uveitis.1 Tattoo-associated uveitis without systemic

sarcoidosis is a rare entity first described in a case

series half a century ago.2 The disease is characterised

by recurrent episodes of uveitis in conjunction

with raised and indurated tattoo, while histology

of affected skin demonstrates florid non-caseating

granulomatous reaction indistinguishable from

tattoo granuloma in systemic sarcoidosis.3 The exact

pathogenesis is unknown, but it was believed to be

a type of delayed hypersensitivity reaction to tattoo

pigments.3 Treatment is mainly to control ocular

inflammation by topical and systemic steroid, with

or without steroid-sparing agent. Tattoo excision has

been reported to be useful in limiting recurrences.1 3

However, the extensive tattoo involvement in our

patient rendered excision impractical.

In summary, the clinical photos illustrate a rare

case of tattoo-associated uveitis, highlighting the

importance of inquiry into tattoo history and skin

examination of tattoos in a patient with recurrent

uveitis.

Author contributions

Concept or design: CY Mak, ME Brelen, AL Young.

Acquisition of data: CY Mak, AZ Chan, CMT Cheung.

Analysis or interpretation of data: CY Mak, M Ho, LPL Iu, PCL Choi.

Drafting of the manuscript: CY Mak, M Ho, AZ Chan.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: CY Mak, AZ Chan, CMT Cheung.

Analysis or interpretation of data: CY Mak, M Ho, LPL Iu, PCL Choi.

Drafting of the manuscript: CY Mak, M Ho, AZ Chan.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This pictorial medicine paper received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-forprofit

sectors.

Ethics approval

This patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient provided written informed consent for

all treatments and procedures and for publication of clinical

photos.

References

1. Kluger N. Tattoo-associated uveitis with or without systemic sarcoidosis: a comparative review of the

literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018;32:1852-61. Crossref

2. Rorsman H, Brehmer-Andersson E, Dahlquist I, et al. Tattoo granuloma and uveitis. Lancet 1969;2:27-8. Crossref

3. Ostheimer TA, Burkholder BM, Leung TG, Butler NJ, Dunn JP, Thorne JE. Tattoo-associated uveitis. Am J

Ophthalmol 2014;158:637-43.e1. Crossref