© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Emergency single-port laparoscopic partial

adrenalectomy for adrenal abscess in an adult

with disseminated Streptococcus pyogenes

bacteraemia: a case report

DS Tam, MB, BS; CH Man, FHKAM (Surgery); KW Wong, FHKAM (Surgery); KC Ng, FHKAM (Surgery)

Department of Surgery, Caritas Medical Centre, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr DS Tam (dicksontamds@gmail.com)

Case report

A 55-year-old man with unremarkable past health

who was a chronic smoker and drinker presented

to the emergency department in July 2019 with

2-day history of severe epigastric pain and fever.

On admission, the patient was septic-looking and

clinically unstable (blood pressure 138/94 mm Hg,

pulse 115 bpm, temperature 39.2°C). Physical

examination revealed epigastric tenderness and

guarding. Blood tests showed an elevated white

cell count of 20.89 × 109/L (reference range,

3.70-9.20 × 109/L) and C-reactive protein level of

>294 mg/L (reference range, <5.0 mg/L). Chest and

abdominal plain radiograph showed no free gas

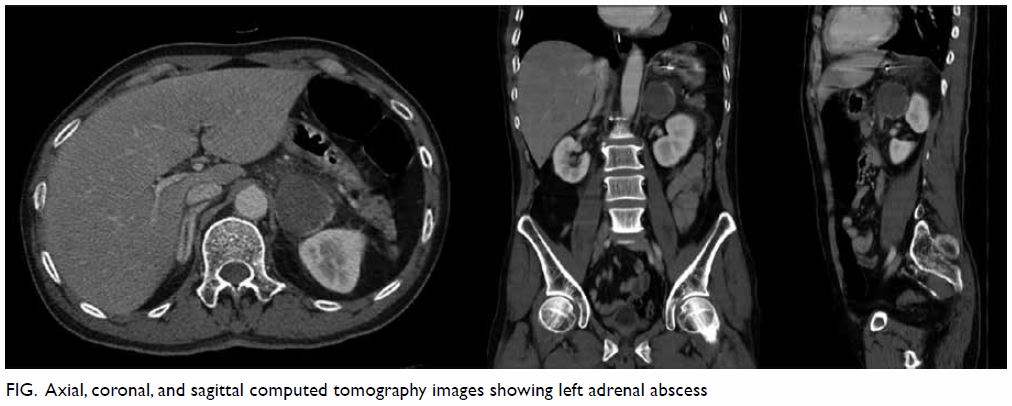

under the diaphragm. Urgent contrast computed

tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis

demonstrated a 4.5 cm × 4 cm × 4 cm minimally

enhancing hypodense lesion in the left adrenal

gland with surrounding infiltrative changes (Fig).

The patient underwent fluid resuscitation and was

prescribed piperacillin/tazobactam. Retroperitoneal

CT-guided drainage of the left adrenal collection

performed the next day yielded 6 mL of pus. The

patient also reported right knee pain for 1 week. Physical examination revealed a right knee effusion.

Right knee tapping yielded straw-coloured joint

fluid, urgent Gram stain of which showed gram-positive

cocci. Emergency right knee arthroscopy

with synovectomy was performed for septic arthritis.

Intraoperatively there was pus within the knee

joint. Adrenal fluid aspirate, joint fluid and blood

culture all grew Streptococcus pyogenes (sensitive to

penicillin). However, his swinging fever persisted.

Extensive workup for other septic foci, including

urine and sputum culture, nasal swab for viruses

and bone marrow examination were all negative as

were autoimmune markers and hepatitis and human

immunodeficiency virus serology. He later developed

sepsis-induced congestive heart failure with acute

pulmonary oedema. Echocardiogram showed no

valvular vegetation. The patient’s haemodynamics

gradually improved with antibiotics.

Sepsis again worsened with septic shock

and desaturation. New chest radiograph revealed

pulmonary congestion and a further CT scan

showed interval shrinkage of the left adrenal abscess

(3.2 cm × 2.9 cm × 2.6 cm). The left adrenal abscess

was suspected as the remaining septic focus. Image-guided drainage was not possible since there was no

safety window. The abscess was small and very close

to the aorta so emergency single-port laparoscopic

left partial adrenalectomy was performed for

definitive drainage.

The patient underwent general anaesthesia and

was placed in a right lateral decubitus position. We

adopted a transperitoneal approach with a 3-cm left

subcostal incision. An OCTO-port was inserted, and

pneumoperitoneum was established. Laparoscopy

showed hyperaemic and inflammatory adhesions

around the left adrenal gland. Splenic flexure was

then taken down. The spleen and anterior surface

of the left kidney were mobilised to enable a clearer

view of the left adrenal gland. Initial tapping yielded

no pus so the left adrenal gland was opened and

the abscess cavity entered. Pus was drained and the

cavity irrigated with normal saline. The superficial

part of the abscess and its overlying adrenal tissue

were then resected. A 15-French silicon drain was

placed at the left adrenal bed. Finally, the fascial

defect and skin were closed with an interrupted 2-0

absorbable suture and skin staples, respectively. The

operating time was 210 minutes. Interval CT on

postoperative day 4 showed disappearance of the left

adrenal abscess. The surgical drain was removed on

day 5. Private positron emission tomography–CT

scan on day 15 showed no adrenal collection. The

patient was discharged on postoperative day 33.

Histopathology was reported as abscess.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case

of adrenal abscess treated by emergency single-port

laparoscopic partial adrenalectomy. Adrenal

abscesses are uncommon in neonates and much rarer

in adults. In the literature, most adult cases are due to

disseminated infection in an immunocompromised

host or postoperative complications. One rare case

of acute appendicitis complicating adrenal abscess

has been reported.1 Iatrogenic cause due to fine needle aspiration of an adrenal nodule has also been

reported once only.2 Identified pathogens include Escherichia coli, Mycobacterium tuberculosis,

Nocardia, Salmonella, and Streptococcus spp.

Invasive group A streptococcus causing abdominal

or peritoneal infections is rare.3 Adrenal abscess can present as fever, malaise, abdominal, or back pain.

Diagnosis is by imaging, preferably CT. Principles

of management are adequate drainage and systemic

antimicrobials. Percutaneous image-guided drainage

is useful for small and simple abscesses. Those that

are large, multiloculated, lacking a safety window

for needle insertion or in which percutaneous

drainage has failed should be treated with surgical

drainage.

After the first single-port adrenalectomy

reported in 2005, there has been increasing evidence that laparo-endoscopic single-site adrenalectomy

is safe and has a comparable surgical outcome to a

conventional approach but with less wound pain and

better cosmesis.4 Partial adrenalectomy has been

applied for aldosterone-producing adenoma but

is more challenging than total adrenalectomy as it

is more difficult to gain a negative margin, ensure

haemostasis, and minimise damage to the remaining

adrenal tissue.5 The first single-port partial

adrenalectomy was reported in 2010. Currently there

is no solid evidence suggesting the best approach of

surgery. In our centre, we performed our first single-port

adrenalectomy in 2009. Since then, we routinely

perform this technique for left-sided adrenal lesions

and the surgical approach is transperitoneal.

Emergency adrenalectomy is much less well

investigated. The most common indication is

pheochromocytoma multisystem crisis, an acute

severe presentation of catecholamine-induced

hemodynamic instability causing end-organ damage

or dysfunction.6 Emergency surgery is the treatment

of choice, but the definitive timing of surgery is

controversial.

Most reported cases that require surgical

drainage have been treated by open surgery,7 except

two cases where standard laparoscopic drainage

was performed. Our patient is the first case of

adrenal abscess treated by emergency single-port

laparoscopic partial adrenalectomy. Intraoperatively,

initial tapping of the abscess yielded no pus. Hence,

we decided to proceed with partial adrenalectomy,

to resect as little overlying adrenal tissue as possible,

to drain the abscess adequately. At the end of surgery

when inserting the silicon drain, we did not insert

the drain via the same abdominal fascial defect at the

OCTO-port to prevent incisional hernia. The drain

exited the fascia adjacent to the fascial defect of the

OCTO-port, then exited the skin at the same port

site wound via a subcutaneous tunnel. There were no

surgical complications and postoperative recovery

was smooth.

In summary, adrenal abscess is rare in healthy

adults but can cause severe sepsis. Prompt surgery

is important when conservative management

fails. We demonstrate that emergency single-port

laparoscopic partial adrenalectomy is a feasible

approach for surgical drainage. More large-scale

studies and randomised trials are needed to provide

more solid evidence to support use of single-port

adrenalectomy in an emergency setting.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept or design of the study, acquisition of the data, analysis or interpretation of the

data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the

manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors

had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved

the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its

accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This case report received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient gave written informed consent for all

investigations and interventions.

References

1. Dimofte G, Dubei L, Lozneanu LG, Ursulescu C, Grigora Scedil M. Right adrenal abscess—an unusual

complication of acute appendicitis. Rom J Gastroenterol

2004;13:241-4.

2. Masmiquel L, Hernandez-Pascual C, Simo R, Mesa J. Adrenal abscess as a complication of adrenal fine-needle

biopsy. Am J Med 1993;95:244-5. Crossref

3. Nelson GE, Pondo T, Toews KA, et al. Epidemiology of

invasive group A Streptococcal infections in the United

States, 2005-2012. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63:478-86. Crossref

4. Chung SD, Huang CY, Wang SM, Tai HC, Tsai YC,

Chueh SC. Laparoendoscopic single-site (LESS)

retroperitoneal adrenalectomy using a homemade single-access

platform and standard laparoscopic instruments.

Surg Endosc 2011;25:1251-6. Crossref

5. Yu CC, Tsai YC. Current surgical technique and outcomes of laparoendoscopic single-site adrenalectomy. Urol Sci

2017;28:59-62. Crossref

6. Wu R, Tong N, Chen X, et al. Pheochromocytoma crisis

presenting with hypotension, hemoptysis, and abnormal

liver function: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore)

2018;97:e11054. Crossref

7. Jackson C, McCullar B, Joglekar K, Seth A, Pokharna H. Disseminated nocardia farcinica pneumonia with left

adrenal gland abscess. Cureus 2017;9:e1160. Crossref