Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Traumatic epidural pneumorrhachis: a case

report

YY Yang, MB, BS1; CB Chua, MD1; CW Hsu, MD, PhD1,2; KH Lee, MD, PhD1,2

1 Department of Emergency Medicine, E-Da Hospital, I-Shou University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

2 School of Medicine for International Students, I-Shou University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

Corresponding author: Dr KH Lee (peter1055@gmail.com)

Case report

A 62-year-old man with no known systemic disease

was brought to an emergency department by

ambulance. He was found trapped in a car after

colliding with a bridge and was found to have been

driving under the influence of alcohol. On arrival,

he complained of headache, neck pain, and chest

pain. Physical examination revealed blood pressure

of 133/71 mm Hg, heart rate 71 beats per minute,

respiratory rate 22 breaths per minute, and oxygen

saturation on air of 93%. He appeared intoxicated

and was disorientated with a score of 13 (E3V4M6)

on the Glasgow Coma Scale. His pupil size was

3.5 mm with bilateral normal reaction to light.

A thorough neurological examination could not

be performed but the patient was able to move all

four limbs without limitation. Nonetheless a scalp

laceration, upper back tenderness and left lower

cervical crepitus were evident during palpation.

Chest examination revealed bilateral equal breath

sounds but some basal crackles and a left flank

abrasion about 3 × 4 cm in size. Haemogram and

biochemistry test results were within normal limits

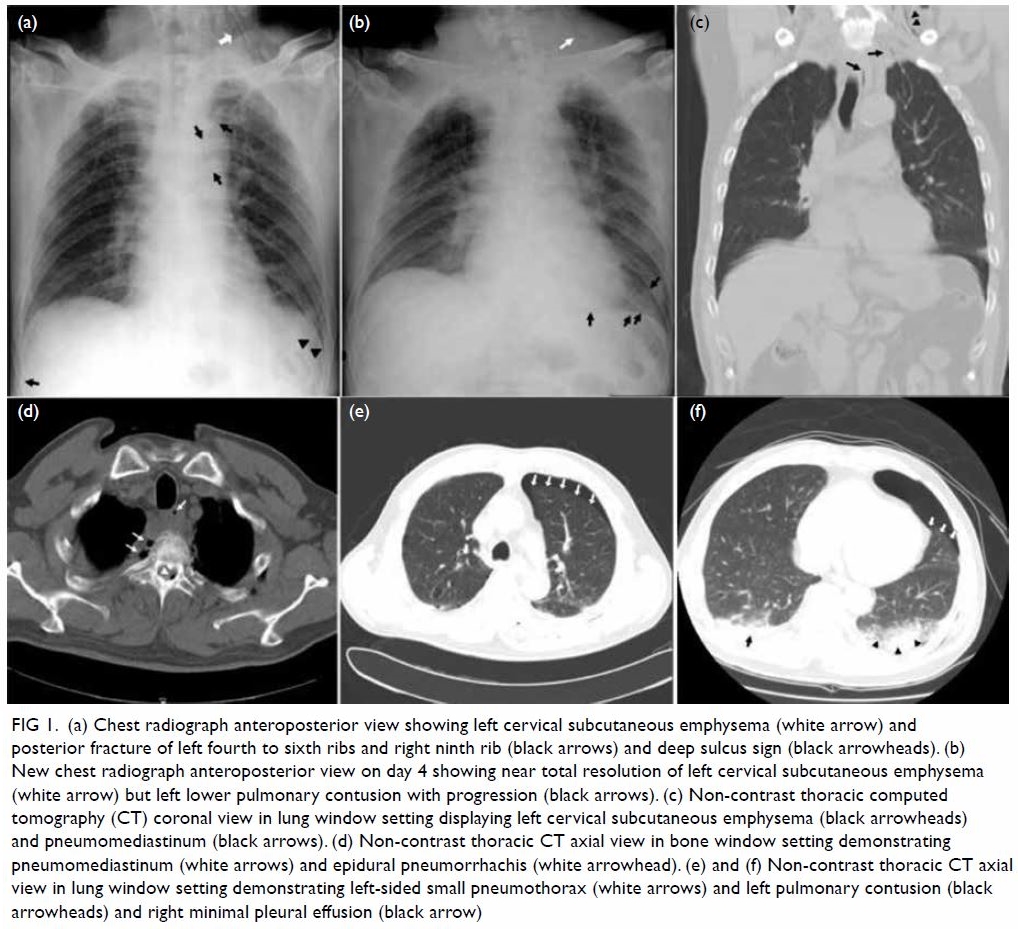

but serum alcohol level was elevated at 2.48 g/L. Chest radiography revealed a posterior fracture at

the left fourth to sixth ribs and right ninth rib as well

as left cervical subcutaneous emphysema that raised

the suspicion of barotrauma associated with chest

trauma (Fig 1). In view of the possibility of barotrauma

and intracranial injuries, further evaluation with

computed tomography (CT) of the brain and chest

was arranged. The former was normal and the latter

confirmed right first to second posterior ribs and

left third to sixth posterior ribs fractures, as well as a

small left-sided pneumothorax, bilateral pulmonary

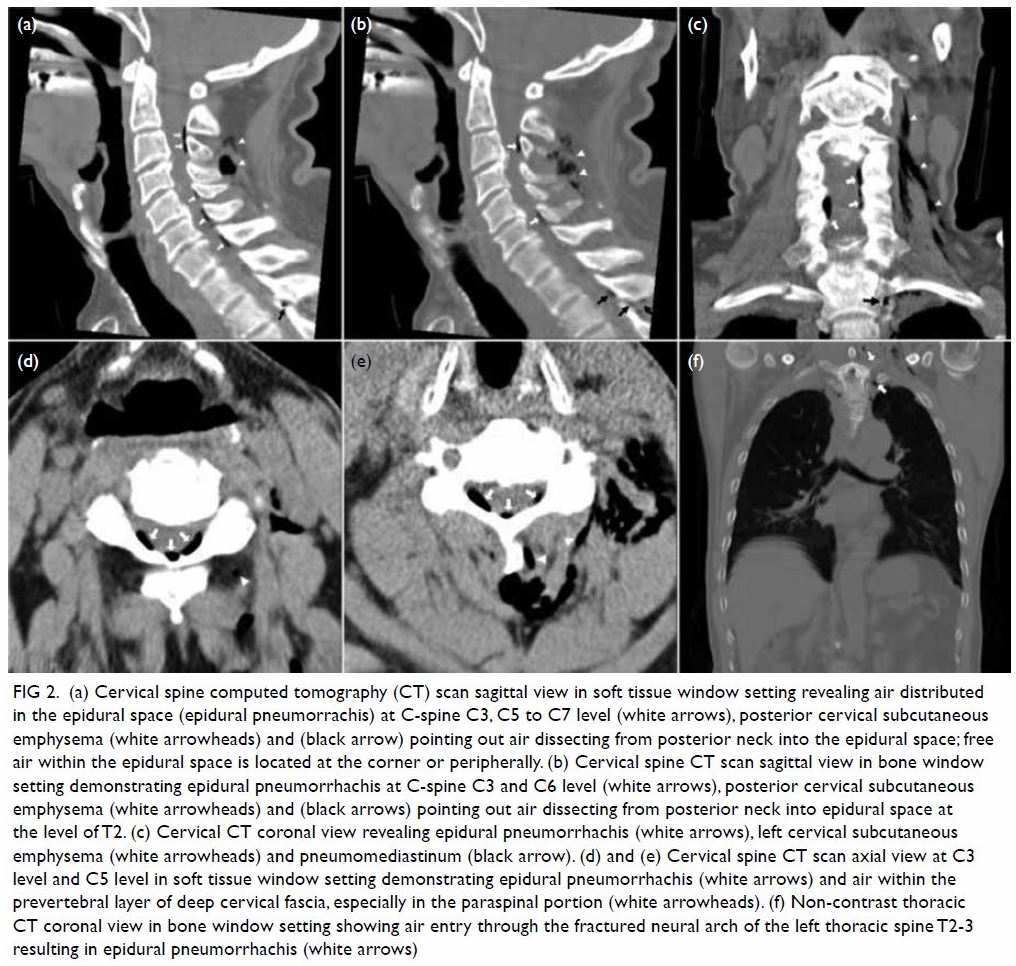

contusions, and pneumomediastinum. Notably, free

air accumulated in the posterior epidural spaces

of the cervical and thoracic spine as well as in the

left retrospinal and paraspinal muscle layers with

accompanying left second and third thoracic spine

posterior neural arch fracture in cervical spine CT

scan (Fig 2); these findings were compatible with

epidural pneumorrhachis. Additionally, air was

seen dissecting from the posterior neck into the

epidural space. A neurosurgeon recommended close observation rather than surgical intervention for

both the epidural pneumorrhachis and thoracic spine

fracture. The patient was admitted to the thoracic

surgical ward where he received conservative

therapy for rib fractures, pneumothorax and

pneumomediastinum including meperidine for pain

control and oxygen therapy via a nasal cannula at

3 L/min. New chest radiographs were taken on day 4

after surgery. Cervical emphysema had mostly

resolved but there was progression of pulmonary

contusion with bilateral minimal pleural effusions.

The patient also exhibited wheezing and dyspnoea

that warranted inhaled bronchodilators and systemic

steroid therapy. The patient was discharged on day

12 after surgery with symptom improvement; no

neurological sequelae were noted during follow-up

at the out-patient department.

Figure 1. (a) Chest radiograph anteroposterior view showing left cervical subcutaneous emphysema (white arrow) and posterior fracture of left fourth to sixth ribs and right ninth rib (black arrows) and deep sulcus sign (black arrowheads). (b) New chest radiograph anteroposterior view on day 4 showing near total resolution of left cervical subcutaneous emphysema (white arrow) but left lower pulmonary contusion with progression (black arrows). (c) Non-contrast thoracic computed tomography (CT) coronal view in lung window setting displaying left cervical subcutaneous emphysema (black arrowheads) and pneumomediastinum (black arrows). (d) Non-contrast thoracic CT axial view in bone window setting demonstrating pneumomediastinum (white arrows) and epidural pneumorrhachis (white arrowhead). (e) and (f) Non-contrast thoracic CT axial view in lung window setting demonstrating left-sided small pneumothorax (white arrows) and left pulmonary contusion (black arrowheads) and right minimal pleural effusion (black arrow)

Figure 2. (a) Cervical spine computed tomography (CT) scan sagittal view in soft tissue window setting revealing air distributed in the epidural space (epidural pneumorrachis) at C-spine C3, C5 to C7 level (white arrows), posterior cervical subcutaneous emphysema (white arrowheads) and (black arrow) pointing out air dissecting from posterior neck into the epidural space; free air within the epidural space is located at the corner or peripherally. (b) Cervical spine CT scan sagittal view in bone window setting demonstrating epidural pneumorrhachis at C-spine C3 and C6 level (white arrows), posterior cervical subcutaneous emphysema (white arrowheads) and (black arrows) pointing out air dissecting from posterior neck into epidural space at the level of T2. (c) Cervical CT coronal view revealing epidural pneumorrhachis (white arrows), left cervical subcutaneous emphysema (white arrowheads) and pneumomediastinum (black arrow). (d) and (e) Cervical spine CT scan axial view at C3 level and C5 level in soft tissue window setting demonstrating epidural pneumorrhachis (white arrows) and air within the prevertebral layer of deep cervical fascia, especially in the paraspinal portion (white arrowheads). (f) Non-contrast thoracic CT coronal view in bone window setting showing air entry through the fractured neural arch of the left thoracic spine T2-3 resulting in epidural pneumorrhachis (white arrows)

Discussion

Pneumorrachis (PRS) is characterised by the

presence of air within the spinal canal and

can be classified according to its location as

subarachnoid or epidural PRS. Each is associated

with different pathophysiological mechanisms

and causes. It may result non-traumatically from

spinal degeneration, gas-producing infections,

or spontaneous pneumomediastinum in patients

with asthma. Iatrogenic PRS may occur following

a surgical procedure, epidural anaesthesia, or

lumbar puncture but PRS following trauma is rare.1

Almost all types of PRS are found in association

with air distribution in other compartments and

cavities of the body. For example, PRS is observed in

conjunction with pneumocephalus, pneumothorax,

pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium, or

subcutaneous emphysema. Pneumorrachis following

trauma is rare and arises from the presence of air

in the posterior mediastinum or retropharyngeal

space dissecting along the fascial planes from the

posterior mediastinum or retropharyngeal space

through the neural foramina into the epidural space

under the driving pressure of a pneumothorax and

pneumomediastinum and low resistance of loose

connective tissue.2

Epidural PRS has been reported to occur most commonly secondary to traumatic

pneumomediastinum. Neurological deficits have

not been reported in epidural PRS secondary to

trauma. In contrast, traumatic subarachnoid PRS

is almost always secondary to major trauma and

skull bone fractures, and indicates severe injury

and possible association with complications

such as tension pneumocephalus or meningitis.3

Various neurological deficits, such as acute lumbar

root compression, chronic radiculopathy, and

cauda equina syndrome may occur. It is therefore

important to identify air in the epidural space and

subarachnoid space to enable prompt and adequate

management.4 The possible mechanism of PRS in our

patient was air entry into the epidural space because

of pneumomediastinum, left-sided pneumothorax

and subcutaneous emphysema extending through

the fractured neural arch of the thoracic spines into

the epidural space; these conditions fulfil the criteria

for benign traumatic PRS. Criteria for a diagnosis of benign traumatic epidural PRS include substantial

pneumomediastinum with extensive subcutaneous

emphysema due to thoracic trauma.4 There may also

be incidental findings of small amounts of epidural

air demonstrable only on CT and unrelated to spinal

trauma. “Benign” epidural PRS can be managed

conservatively with spontaneous resolution of

epidural air.4 Repeat or further neuroimaging studies

are not routinely provided in cases of epidural PRS,

provided there is no new or progressive neurological

deficit. Three cases have been reported with complete

resolution of PRS on follow-up CT scan after 4 to

14 days.5 6 7

The PRS is usually asymptomatic and an

accidental finding on CT images while evaluating

other severe or life-threatening torso injuries.

Although CT is the gold standard for diagnosis, it

is difficult to differentiate epidural and subarachnoid

PRS. Nonetheless in the former, air is collected at

the corner or peripherally unlike subarachnoid PRS where it is distributed more centrally in the canal

based on normal anatomy. Magnetic resonance

imaging or intrathecal contrast CT can distinguish

intradural from extradural air.7 In most cases of

epidural PRS, the air reabsorbs spontaneously

without recurrence and the patient can be managed

conservatively.1 In subarachnoid PRS, timely

consultation with a neurosurgeon for decompression

of nerve root injuries, tension pneumocephalus and

exploratory surgery by a chest surgeon to detect

severe thoracic trauma is vital. Impressively, Avci

et al5 reported a case of complete resolution of

subarachnoid PRS on the fifth day of admission

with recovery of neurological deficit after chest tube

insertion. They concluded that the negative pressure

of the chest drain to withdraw the air supported the

hypothesis of a one-way valve mechanism in which

high pressure air travels through fascial layers but

is unable to return. The routine use of antibiotic is not recommended in either type unless meningitis develops.1

Conclusion

Traumatic PRS is rare and an incidental radiological

finding. Epidural PRS is often self-limiting with a

good prognosis. Although most patients can be

managed conservatively, prompt recognition of

subarachnoid PRS with neurological deficits and

other concurrent life-threatening torso injuries is

vital.

Author contributions

Concept or design: KH Lee.

Acquisition of data: YY Yang.

Analysis or interpretation of data: CB Chua.

Drafting of the manuscript: YY Yang and KH Lee.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: CW Hsu.

Acquisition of data: YY Yang.

Analysis or interpretation of data: CB Chua.

Drafting of the manuscript: YY Yang and KH Lee.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: CW Hsu.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We would like to extend our special thanks to Dr Cheng-yang

Lee, Department of Medical Imaging, Chi Mei Medical Center,

Tainan, Taiwan who provided insight and expertise on the

image interpretation that greatly improved our manuscript.

Funding/support

All authors have no commercial association, such as

consultancies, stock ownership or other equity interests or

patent-licensing arrangements.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient provided written

informed consent for all treatments and procedures.

References

1. Oertel MF, Korinth MC, Reinges MH, Krings T, Terbeck S, Gilsbach JM. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of

pneumorrhachis. Eur Spine J 2006;15 Suppl 5:636-43. Crossref

2. Defouilloy C, Galy C, Lobjoie E, Strunski V, Ossart M. Epidurual pneumatosis: A benign complication of benign

pneumomediastinum. Eur Respir J 1995;8:1806-7. Crossref

3. Goh BK, Yeo AW. Traumatic pneumorrhachis. J Trauma

2005;58:875-9. Crossref

4. Willing SJ. Epidural pneumatosis: a benign entity in trauma patients. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1991;12:345.

5. Avci İ, Başkurt O, Şirinoğlu D, Aydin MV. Rapid

disappearance of pneumorrhachis after chest tube

placement. Turk J Emerg Med 2019;19:146-8. Crossref

6. Kim SW, Seo HJ. Symptomatic epidural pneumorrhachis: a rare entity. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2013;54:65-7. Crossref

7. Pfeifle C, Henkelmann R, von der Höh N, et al. Traumatic pneumorrhachis. Injury 2020;51:267-70. Crossref