© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Gas embolism and hyperbaric oxygen therapy:

a case series

Jeffrey CW Chau, MB, BS, MRCS(Ed)1; Joe KS Leung, MB, ChB, FRCS1; WW Yan, FRCP, FHKCP2

1 Department of Accident and Emergency, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Intensive Care Unit, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Jeffrey CW Chau (drjhealthcare@gmail.com)

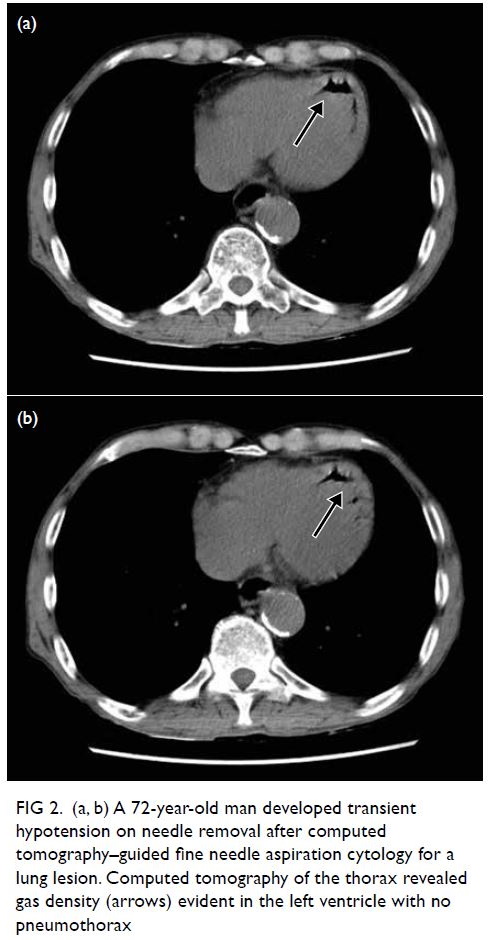

Case report

Patient 1

A 79-year-old man presented with left-sided

weakness, drowsiness and dysphasia following left

atrial appendage occlusion implantation in a cardiac

intensive care unit. A sudden drop in systolic blood

pressure to 40 mmHg was noted. Echocardiogram

and angiogram revealed no obvious coronary artery

disease. Computed tomography (CT) of the brain

showed no major vessel occlusion or gas pocket. A

new CT of the brain showed more established infarct

and oedema. Four sessions of hyperbaric oxygen

therapy (HBOT) were conducted in accordance with

United States Navy Treatment Tables (USNTT)1: two USNTT6 and two USNTT5.

Patient 2

A 40-year-old woman was admitted to a surgical

unit for suspected acute appendicitis. Urgent CT

of the abdomen with contrast was performed, but

approximately 60 mL of air was injected intravenously

during the procedure and gas was evident in the

right ventricle. Luckily, she was asymptomatic as the

gas emboli had entered only the venous system and

remained in the heart. One session of HBOT was

conducted with USNTT6.

Patient 3

A 57-year-old woman underwent fine needle

aspiration cytology under CT guidance for lung

mass. The patient developed sudden onset bilateral

anopia and left upper limb weakness during the

procedure. Computed tomography brain and thorax

identified a small gas embolism in the pulmonary

vein with pulmonary haemorrhage. No obvious gas

bubble was noted in the brain. A total of four sessions

of HBOT were conducted with two USNTT6 and

two USNTT5.

Patient 4

An 84-year-old man underwent CT-guided lung

biopsy for right lung mass but experienced an acute

deterioration in Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score. Urgent CT of the brain showed multiple acute gas

emboli and confirmed the diagnosis of cerebral

arterial gas embolism (AGE). On arrival at the HBOT

centre, he had GCS of 13/15 and right limb weakness

with power of 1/5 and 3/5, respectively. Two sessions

of HBOT were conducted with USNTT6.

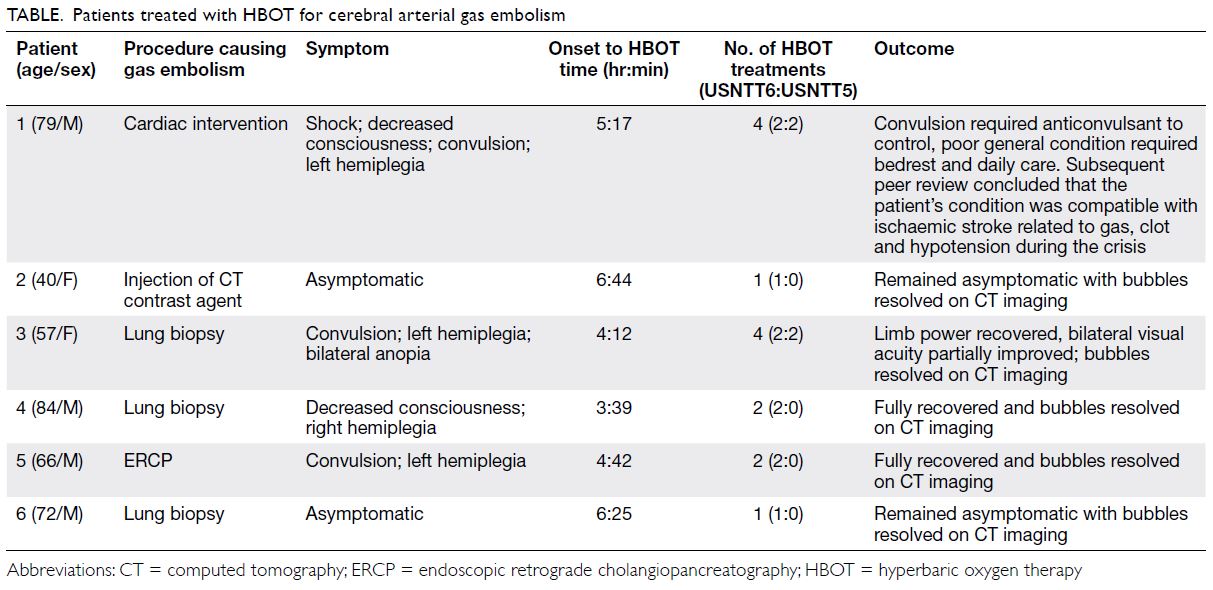

Patient 5

A 66-year-old man with biliary pancreatitis

underwent urgent endoscopic retrograde

cholangiopancreatography. After the procedure he

developed left-sided weakness with limb power of

0/5 after 5 minutes. Urgent CT of the brain revealed

branching gas densities at the sulcal space of his

right frontal and parietal lobes (Fig 1). Two sessions

of HBOT with USNTT6 were conducted and the

patient’s symptoms considerably improved.

Figure 1. (a, b) A 66-year-old man with biliary pancreatitis developed left-sided weakness 5 minutes after urgent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Computed tomography of the brain revealed branching gas density in the right frontal and parietal lobes (arrows)

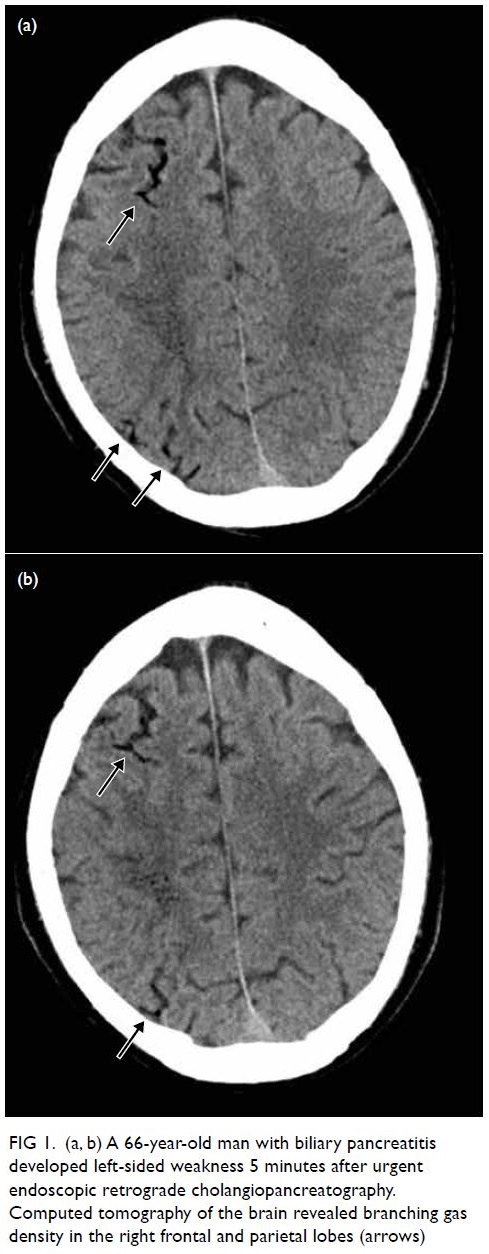

Patient 6

A 72-year-old man underwent CT-guided fine

needle aspiration cytology for a lung lesion. The

patient developed transient hypotension on

needle removal and CT of the thorax revealed gas

embolism in his left ventricle with no pneumothorax

(Fig 2). The patient remained asymptomatic with

no neurological deficit. Gas embolism had been

introduced through the pulmonary circulation but

remained in the heart, avoiding the complication of

cerebral arterial occlusion. One session of HBOT

was conducted with USNTT6.

Figure 2. (a, b) A 72-year-old man developed transient hypotension on needle removal after computed tomography–guided fine needle aspiration cytology for a lung lesion. Computed tomography of the thorax revealed gas density (arrows) evident in the left ventricle with no pneumothorax

Discussion

Gas embolism is a serious and life-threatening

condition. It is usually iatrogenic and should be

treated promptly to prevent serious complications

such as cerebral AGE. It presents with sudden

deterioration in neurological and haemodynamic

status following risky medical procedures, most

notably lung biopsy and cardiac interventions. This

case report revealed six patients with gas embolism:

five with AGE and one with venous gas embolism.

Four patients with AGE manifested as cerebral AGE

with neurological deficits such as limb weakness and

anopia (Table).

Rationale for using hyperbaric oxygen

therapy

As soon as AGE is suspected, the patient should

start receiving 100% high-flow oxygen and be

placed in the right lateral decubitus position. The

definitive treatment for AGE is HBOT with 100%

oxygen, although no randomised controlled trials have been conducted to confirm its efficacy in this

disease. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy “crushes” the

bubbles with pressure, accelerates gas diffusion

and bubble resolution with oxygen, oxygenates

ischaemic tissue, reduces cerebral oedema, and

decreases neutrophil adhesion to the endothelium.1 2

A retrospective study in France showed that the

initial neurological symptoms were impaired

consciousness (70%), focal motor deficits (60%),

seizures (11%), visual disturbance (10%), dysarthria/aphasia (5%) and vertigo (5%). In all, 26% of patients

were haemodynamically unstable and subject to

hypotension, circulatory collapse, and cardiac arrest.

Respiratory disturbances such as dyspnoea, cough or

chest pain were present in 23% of patients.3

In a study of 45 patients with AGE, good

neurological outcome was achieved in 27 (60%)

of them.4 Time to receipt of HBOT was the only

statistically significant factor predictive of a good outcome with mean delay 8.8 hours.4 Although

probability of a good outcome is highest when HBOT

is administered as soon as possible, a good response

can still be obtained if treatment is delayed for longer

than 24 hours.3 5 There is a tendency for patients

with AGE to deteriorate after their initial apparent

recovery; thus, early HBOT is still recommended

for patients with a seemingly spontaneous recovery.6

Although identification of gas bubbles on CT of the

brain is not a prerequisite to HBOT, early treatment

can also attenuate leucocyte adherence to damaged

endothelium and secondary inflammation that in

turn facilitate the return of blood flow. However, gas

bubbles can persist for several days, and many case

reports have demonstrated the benefit of HBOT

after delays ranging from hours to days. Complete

recovery has been reported in one patient in whom

treatment was delayed for 28 hours. In 2017,

another patient who was deeply comatose with AGE

recovered and was able to lead a functional life after

HBOT had been delayed for 6 days.7 8 In our cases,

all the patients were treated within 7 hours onset of

symptoms. Most fully recovered except for Patient 1.

The aetiology of neurological deterioration in

Patient 1 was likely due to a combination of gas

embolism, clots, and hypotension.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy treatment tables

According to the United States Navy Diving Manual,9

USNTT6 is the standard initial compression therapy

for AGE. It is a table with maximum pressure up to

2.8 atmospheres absolute (ATA) for 1 hour 15 minutes

with slow depressurisation to 1.9 ATA lasting for

2.5 hours. Total treatment time is approximately 4 hours 45 minutes. There is no conclusive evidence

that use of pressure higher than 2.8 ATA has any

advantage. Use of pressure up to 6 ATA poses further

risks to the patient and attending staff, including gas

toxicity and decompression sickness. Typically, one

to three hyperbaric treatments are required to treat

AGE; the clinical condition should be monitored

until there is no further stepwise improvement.

There are reports that up to 10 treatments have been

required to reach a stable condition.10 11

The USNTT5, which is a shorter treatment

used to treat mild decompression sickness, may

be used together with USNTT6 for AGE when

prolonged treatment is required. This treatment

table advises a maximum pressure up to 2.8 ATA for

45 minutes with slow depressurisation to 1.9 ATA for

30 minutes. Total treatment time is approximately

2 hours 15 minutes. According to the Royal Navy

Diving manual,12 which is commonly used in Europe,

RN62 Table is the standard to treat AGE. This

treatment is similar to USNTT6 with a maximum

pressure of 2.8 ATA.

Conclusion

Arterial gas embolism presents in highly variable ways with no pathognomonic signs or symptoms. It

is uncommon to achieve complete consensus on the

diagnosis, and it is common practice to err on the

side of caution. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy should

be initiated as early as possible although delayed

treatment is also effective. Failure to administer

treatment can result in long-term disability.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy should be considered for

any suspected AGE.

Author contributions

Concept or design: JCW Chau.

Acquisition of data: JCW Chau.

Analysis or interpretation of data: JCW Chau.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: JCW Chau.

Analysis or interpretation of data: JCW Chau.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patients were treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The patients provided informed consent for the

treatment/procedures, and verbal consent for publication.

References

1. United States Navy. Diagnosis and treatment of

decompression sickness and arterial gas embolism. In: US

Navy Diving Manual. Revision 7. Vol 5. Available from:

https://www.navsea.navy.mil/Portals/103/Documents/SUPSALV/Diving/US%20DIVING%20MANUAL_REV7.pdf?ver=2017-01-11-102354-393. Accessed 30 Sep 2020.

2. Grim PS, Gottlieb LJ, Boddie A, Batson E. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy. JAMA 1990;263:2216-20. Crossref

3. Blanc P, Boussuges A, Henriette K, Sainty JM, Deleflie M. Iatrogenic cerebral air embolism: importance of an early hyperbaric oxygenation. Intensive Care Med 2002;28:559-63.Crossref

4. Beevor H, Frawley G. Iatrogenic cerebral gas embolism: analysis of the presentation, management and outcomes of patients referred to The Alfred Hospital Hyperbaric Unit.

Diving Hyperb Med 2016;46:15-21.

5. Massey EW, Moon RE, Shelton D, Camporesi EM. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy of iatrogenic air embolism. J

Hyperb Med 1990;5:15-21.

6. Pearson RR, Goad RF. Delayed cerebral edema complicating cerebral arterial gas embolism: case histories. Undersea Biomed Res 1982;9:283-96.

7. Benson J, Adkinson C, Colier R. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy of iatrogenic cerebral arterial gas embolism. Undersea Hyperb Med 2003;30:117-26.

8. Perez MF, Ongkeko Perez JV, Serrano AR, Andal MP, Aldover MC. Delayed hyperbaric intervention in lifethreatening decompression illness. Diving Hyperb Med

2017;47:257-9 Crossref

9. United States Navy. US Navy Diving Manual. Revision 7.

Vol 5: Diving medicine and recompression chamber

operations. 2016. Available from: https://www.navsea.navy.mil/Portals/103/Documents/SUPSALV/Diving/US%20DIVING%20MANUAL_REV7.pdf?ver=2017-01-11-102354-393. Accessed 30 Sep 2020.

10. Vann RD, Butler FK, Mitchell SJ, Moon RE. Decompression illness. Lancet 2011;377:153-64.Crossref

11. Undersea & Hyperbaric Medical Society. UHMA Best

Practice Guidelines: Prevention and Treatment of

Decompression sickness and arterial gas embolism.

Available from: https://www.uhms.org/images/DCS-AGE-Committee/dcsandage_prevandmgt_uhms-fi.pdf. Accessed 30 Sep 2020.

12. Royal Navy, Ministry of Defence. Diving Manual. HM Stationery Office, London; 1972.