Necrotising fasciitis: a rare complication of acute appendicitis

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj166180

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Necrotising fasciitis: a rare complication of acute

appendicitis

Thomas WY Chin, MB, ChB; Koel WS Ko, MB, BS; KH

Tsang, MB, BS, FHKAM (Radiology)

Department of Radiology and Imaging, Queen

Elizabeth Hospital, Yaumatei, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Thomas WY Chin (twychin@gmail.com)

Introduction

Acute appendicitis is a common surgical emergency

that can cause severe complications if diagnosis and management are

delayed.1 Necrotising fasciitis

(NF) is a necrotic infection involving deeper layers of the skin and

subcutaneous tissue that spreads rapidly along the fascia, progressing to

systemic sepsis. It is most commonly induced by injury and is an extremely

rare complication of acute appendicitis. In this article, we present a

case of perforated appendicitis complicated by right thigh and scrotal NF.

Since the condition runs a fulminant clinical course, prompt diagnosis and

early surgical intervention are crucial to reduce mortality.

Case report

A 60-year-old man with good past health presented

to the Accident and Emergency Department of Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong

Kong, in December 2015 with a 6-day history of fever and lower abdominal

pain.

His vital signs on presentation were as follows:

systolic blood pressure 97 mm Hg; diastolic blood pressure 59 mm Hg; pulse

90 beats per minute; and body temperature 38.3°C. Physical examination

revealed lower abdominal and right thigh tenderness without subcutaneous

emphysema. Laboratory data showed leucocytosis (15.5 × 109/L)

with neutrophilia (neutrophils 88.7%) and evidence of acute kidney injury

(estimated glomerular filtration rate 38 mL/min/1.73 m2, serum

creatinine 171 μmol/L).

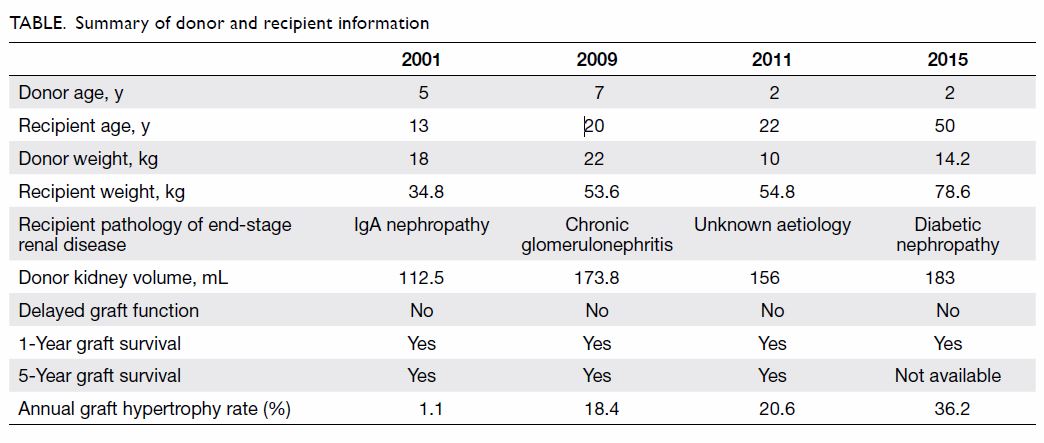

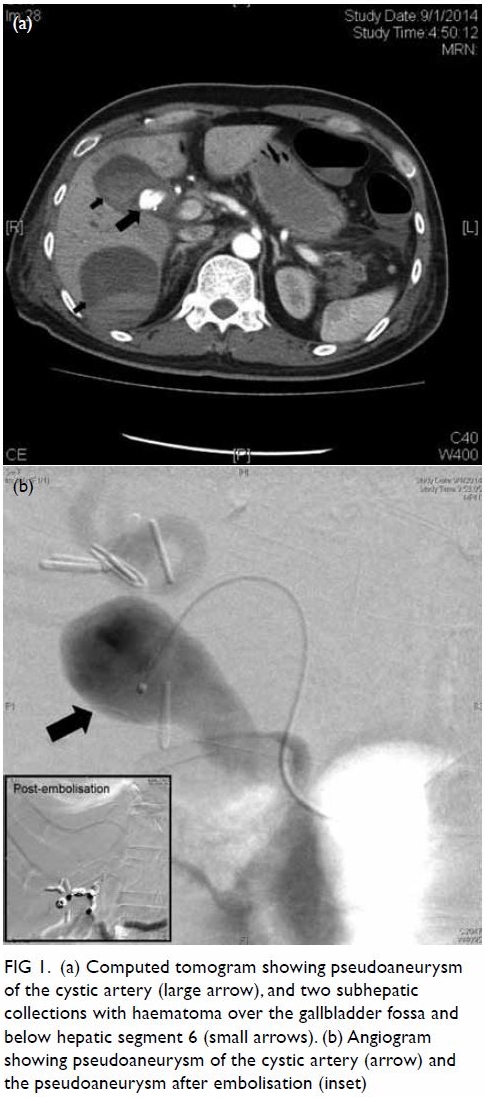

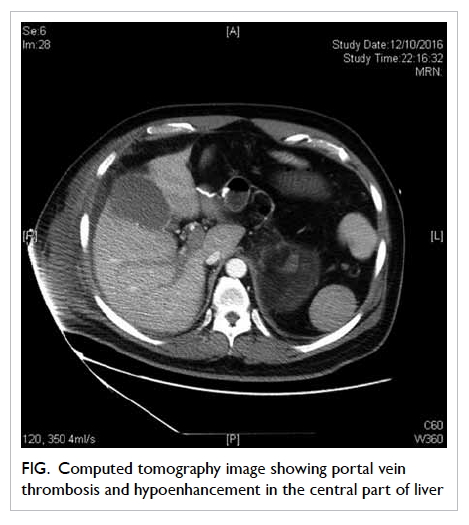

Abdominal, pelvic, and right hip radiographs were

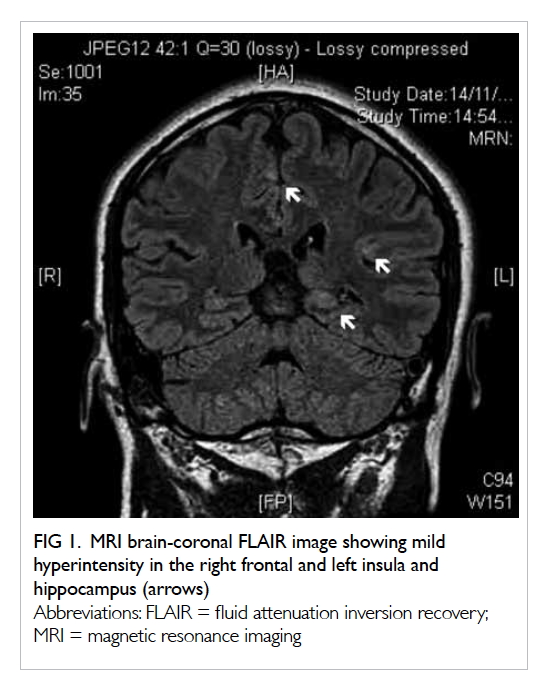

unremarkable. Urgent abdominal and pelvic computed tomographic (CT) scan

revealed a dilated retrocaecal appendix with heterogeneous wall

enhancement, compatible with acute gangrenous appendicitis. There was

rupture at the appendiceal tip, contiguous with a 2.8- × 4.5- × 8.0-cm

gas-containing abscess posterolateral to the ascending colon and caecum (Fig 1). Increased peri-appendiceal and pericaecal

stranding and free gas were noted. Multiple smaller pelvic abscesses were

also observed. An incidental finding of abnormal swelling of the right

upper thigh was noted in the limited coverage of the thigh in the original

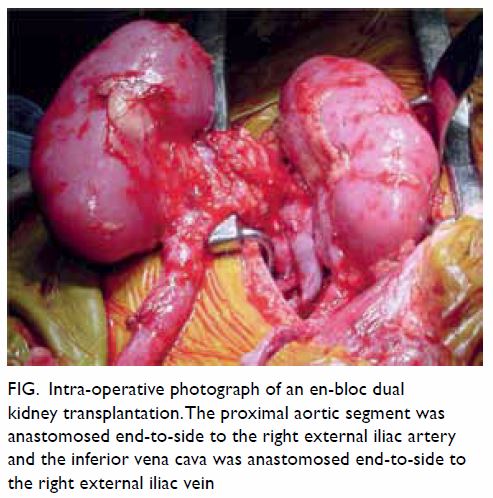

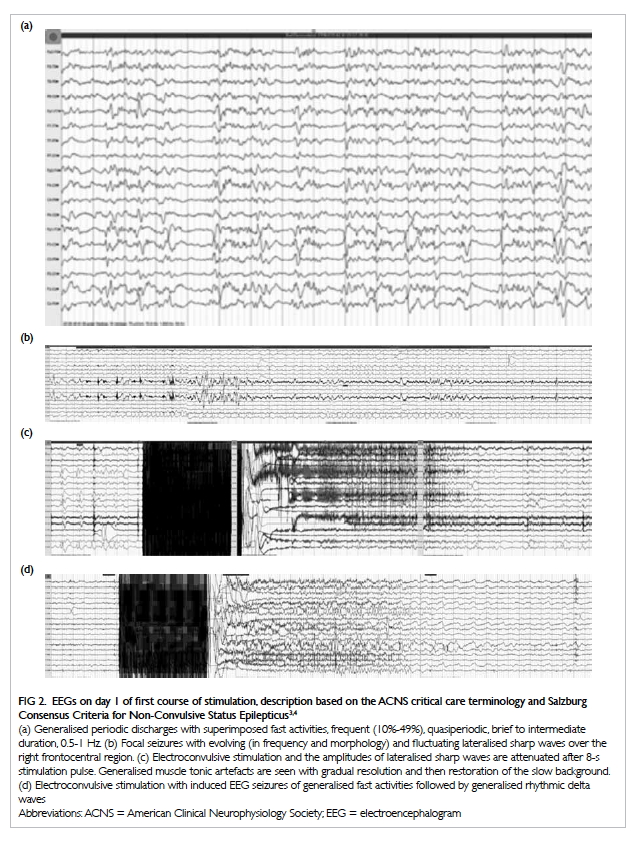

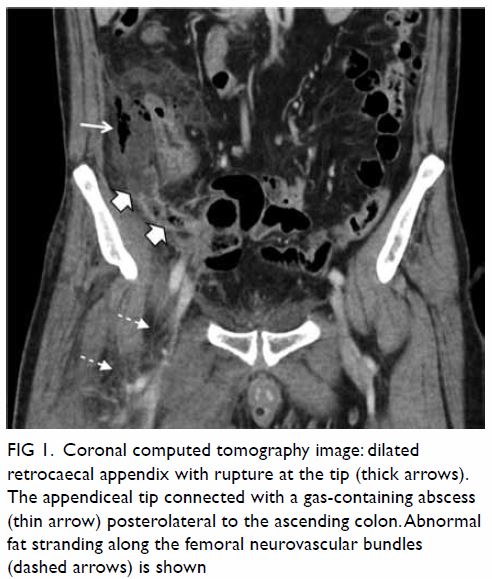

CT scan. Another CT scan including the whole right thigh was performed by

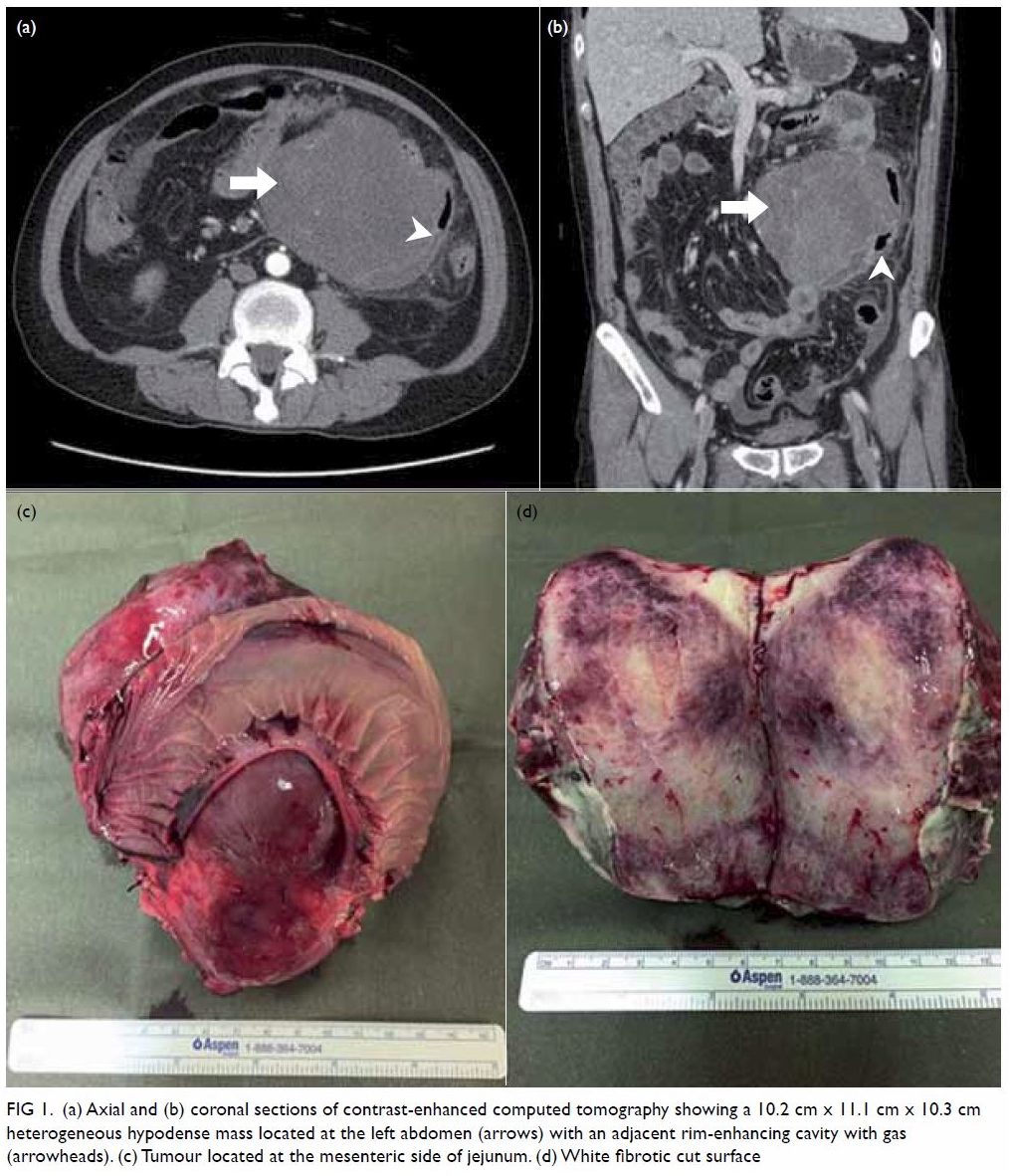

the on-site radiologist. Abnormal high-density fluid and fat stranding

were noted in the subcutaneous layer and intermuscular fascial planes in

the anterior, adductor, and posterior compartments of the right thigh (Fig 2). The thigh muscles were swollen without

discrete abscess formation. No gas density was detected along the fasciae.

The initial overall imaging diagnosis was ruptured acute appendicitis with

peri-appendiceal abscess, complicated by right thigh NF.

Figure 1. Coronal computed tomography image: dilated retrocaecal appendix with rupture at the tip (thick arrows). The appendiceal tip connected with a gas-containing abscess (thin arrow) posterolateral to the ascending colon. Abnormal fat stranding along the femoral neurovascular bundles (dashed arrows) is shown

Figure 2. Coronal computed tomographic image: generalised right thigh swelling. Abnormal high-density fluid and fat stranding in the subcutaneous layer (white thin arrow), intermuscular fascial planes (black arrow) and along the femoral neurovascular bundles (white thick arrow) are shown

Subsequent urgent laparotomy revealed a ruptured

inflamed retrocaecal appendix and an 8-cm retrocolic abscess. Appendectomy

and abscess drainage were performed. These were followed by exploration of

the right thigh that revealed oedematous and necrotic subcutaneous and

deep soft tissues mainly involving the adductor compartment. Multiple

intramuscular abscesses were seen with turbid fluid tracing along the

femoral neurovascular bundles proximally to the pelvic region. Overall

features were compatible with NF. Right above-knee amputation with

excisional debridement was performed in view of the patient’s poor general

condition and extensive involvement.

Culture of the debrided muscle and fascial tissue

yielded Escherichia coli, Bacteroides fragilis, and Streptococcus

milleri. A combination of antibiotics was given, including amikacin,

ampicillin, levofloxacin, linezolid, meropenem, and penicillin G. However,

septic shock persisted with development of multi-organ dysfunction despite

multiple inotropes. Another CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was

performed on postoperative day 1, revealing a grossly swollen scrotum with

hydrocoele (not shown). No intrascrotal gas density was detected. In view

of the patient’s clinical deterioration, urgent scrotal exploration was

performed and revealed extensive scrotal skin necrosis with copious serous

fluid draining from the perineum.

After the second surgery, the patient had

persistent multi-organ failure with clinical deterioration despite

supportive management. He developed acute respiratory distress syndrome

with respiratory failure and disseminated intravascular coagulation with

severe anaemia, further complicated by acute coronary syndrome. The

patient succumbed on the fourth day of hospital admission.

Discussion

The incidence of NF has risen recently owing to an

increased prevalence of patients who are immunocompromised secondary to

diabetes mellitus or treatment for malignancy or human immunodeficiency

virus infection.1 The mortality

rate for NF is high, despite significant advances in antibiotic treatment,

owing to its rapid progression to septic shock and multi-organ failure.1

Common causes of NF include minor trauma, skin

infection, intravenous drug use, and surgical complication.1 The abdomen,

groin, and extremities are the regions most commonly affected by NF.1 2 3 4 5 Necrotising fasciitis is commonly polymicrobial, caused

by virulent toxin-producing bacteria such as Group A haemolytic

streptococci and Staphylococcus aureus. Other causative bacteria

include Bacteroides, Clostridium, Enterobacteriaceae,

Peptostreptococcus, Proteus, Pseudomonas, and Klebsiella.1

The diagnosis of NF is challenging due to its

rarity and non-specific presentation. Usually the early manifestations are

local inflammatory signs and symptoms such as swelling, erythema, and

tenderness, occasionally with fever. However, NF should be suspected when

the severity of pain or clinical status are disproportional to local

findings.5 Laboratory studies show

leucocytosis with predominant neutrophilia,1

but is unfortunately non-specific.5

Presence of soft tissue gas in the absence of penetrating trauma suggests

a diagnosis of NF,2 although the absence of soft tissue gas does not

exclude the diagnosis, as evidenced by our case.

Plain radiographs are usually unhelpful for initial

diagnosis as soft tissue gas is seldom detected until late in the disease

process.1 Magnetic resonance

imaging is superior in delineating soft tissue pathology but is a

suboptimal modality for critically ill patients.2

Computed tomography is the preferred imaging modality, with reported

findings including asymmetric fascial thickening with fat stranding and

subcutaneous gas tracking along fascial planes.2

It also delineates the extent of tissue involvement well and is useful for

monitoring treatment response.

Necrotising fasciitis secondary to perforated

appendicitis is rarely reported. We have found only 18 case reports of NF

caused by acute appendicitis published in the English literature.1 2 3 4 5 The affected regions included the abdominal wall (most

commonly involved), perineum, and thigh. According to Taif and Alrawi,5 there have been only three reported cases of

appendicitis complicated by NF predominantly involving the lower limb. All

cases involved the right thigh, likely from more direct infective spread

along the right femoral neurovascular bundles than the left.

Our case represents a rare but life-threatening

consequence of a common disease despite the absence of risk factors. Early

clinical changes of NF can be subtle. Early recognition, broad-spectrum

antibiotic treatment, and aggressive surgical debridement are the

cornerstones of management for this potentially lethal disease.1 A high index of suspicion is needed in diagnosis such

that emergent surgical intervention can be initiated to improve clinical

outcome.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the design, acquisition

and interpretation of data, drafting of the article, and critical revision

for important intellectual content.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the staff radiographers of

the Department of Radiology and Imaging, Queen Elizabeth Hospital for

their assistance in acquisition of the images.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of

interest. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility

for its accuracy and integrity.

References

1. Chen CW, Hsiao CW, Wu CC, Jao SW, Lee

TY, Kang JC. Necrotizing fasciitis due to acute perforated appendicitis:

case report. J Emerg Med 2010;39:178-80. Crossref

2. Hung YC, Yang FS. Necrotizing

fasciitis—a rare but severe complication of perforated appendicitis.

Radiol Infect Dis 2015;2:81-3. Crossref

3. Hua J, Yao L, He ZG, Xu B, Song ZS.

Necrotizing fasciitis caused by perforated appendicitis: a case report.

Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2015;8:3334-8.

4. Wanis M, Nafie S, Mellon JK. A case of

Fournier’s gangrene in a young immunocompetent male patient resulting from

a delayed diagnosis of appendicitis. J Surg Case Rep 2016;2016:rjw058. Crossref

5. Taif S, Alrawi A. Missed acute

appendicitis presenting as necrotising fasciitis of the thigh. BMJ Case

Rep 2014;2014:bcr2014204247. Crossref