DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154524

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Neurocysticercosis: diagnostic dilemma

Joyce HM Cheng, MB, ChB; Eric MW Man, MB, ChB, FRCR; SY Luk, MB, BS, FRCR; Wendy WC Wong, MB, BS, FRCR

Department of Radiology, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Joyce HM Cheng (chm915@ha.org.hk)

Case report

A 7-year-old Nepalese boy with unremarkable past

health was admitted in July 2013 with a 2-week

history of headache, dizziness, and vomiting that

subsided spontaneously. On admission, he was

afebrile with unremarkable neurological and fundal

examination.

He had been living in Nepal until the age of

5 years and then immigrated to Hong Kong. He

recently travelled to Nepal but had otherwise no

contact history with pigs or febrile persons.

Blood tests were unremarkable except mildly

elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 26 mm/h.

Lumbar puncture yielded normal cerebrospinal fluid

(CSF) white cell count, and protein and glucose level.

Culture of blood and CSF was negative.

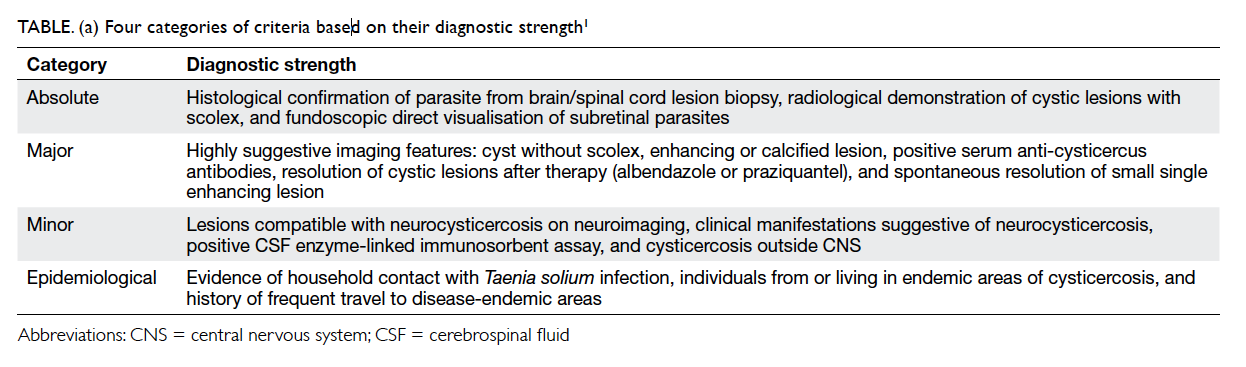

Initial contrast computed tomographic

brain showed two subcentimetre (7 mm and 9

mm) left parieto-occipital adjacent rim-enhancing

lesions (Fig a) with T1-weighted hypointense and T2-weighted/fluid-attenuated

inversion recovery hyperintense signal on contrast

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [Fig b]. Significant perifocal oedema and mass effect

with compression on the left occipital horn was

noted. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy showed a

significant lipid-lactate peak (Fig c), decreased N-acetylaspartate,

and no elevated choline. No amino acid peak was identified. Perfusion imaging with

arterial spine labelling showed no elevated regional

cerebral blood flow (Fig d). Contrast MRI of the spine showed no leptomeningeal enhancement,

intradural nor extradural spinal mass lesions.

Figure. (a) (i) Axial and (ii) coronal reformatted contrast computed tomography showing two rim-enhancing lesions over left parieto-occipital region (arrows). (b) (i) Magnetic resonance (MR) axial images showing T1-weighted (T1W) hypointense and T2-weighted (T2W) hyperintense lesions over left parieto-occipital region with perifocal oedema (arrows); (ii) post-gadolinium T1W MR axial and coronal images showing rim enhancement of the lesions (arrows). (c) Single-voxel MR spectroscopy of left parieto-occipital lobe lesion of (i) short (TE 30), (ii) intermediate (TE 135), and (iii) long (TE 270) echo showing significantly elevated lipid-lactate (1.3 ppm), with a peak doublet centred at 1.3 ppm in TE 30 and TE 270, and inverts in TE 135; N-acetylaspartate peak (2.0 ppm) is decreased; and choline (3.2 ppm) is not elevated. (d) Perfusion imaging in arterial spine labelling showing no significantly elevated regional cerebral blood flow over the left parieto-occipital lesions. (e) T2W and post-gadolinium T1W MR axial images at (i) 2-month and (ii) 5-month intervals showing gradual reduction in the size of the two rim-enhancing lesions over parieto-occipital region (arrows)

Subsequent extensive investigations of blood

(including anti-Taenia solium immunoglobulin G),

CSF, urine and stool for tuberculosis and T solium

were performed, and all results were negative.

Overall review of the clinical presentation,

travel history, laboratory and imaging findings,

and the two cerebral rim-enhancing lesions were

suggestive of an infective process, in particular,

neurocysticercosis or tuberculosis.

After thorough investigations and

interdepartmental discussions, it was decided to treat

the patient as a probable case of neurocysticercosis

and a course of empirical albendazole and

prednisolone was prescribed.

The patient remained asymptomatic after

treatment. Follow-up MRI performed after 2 and 5

months (Fig e) showed reduction in size of the two

cerebral rim-enhancing lesions (3 mm and 1 mm), as

well as the extent of perifocal oedema.

Discussion

Neurocysticercosis is a parasitic infection of

the central nervous system by T solium (ie pork

tapeworm) usually through accidental ingestion of

contaminated food containing its eggs. It has been a

diagnostic challenge in developed areas owing to its

infrequent occurrence, low sensitivity of serological

tests, and highly variable and non-specific

manifestations, both clinically and radiologically. It

is further complicated by clinical and radiological

features that overlap considerably with tuberculosis

infection, particularly in tuberculosis-endemic areas.

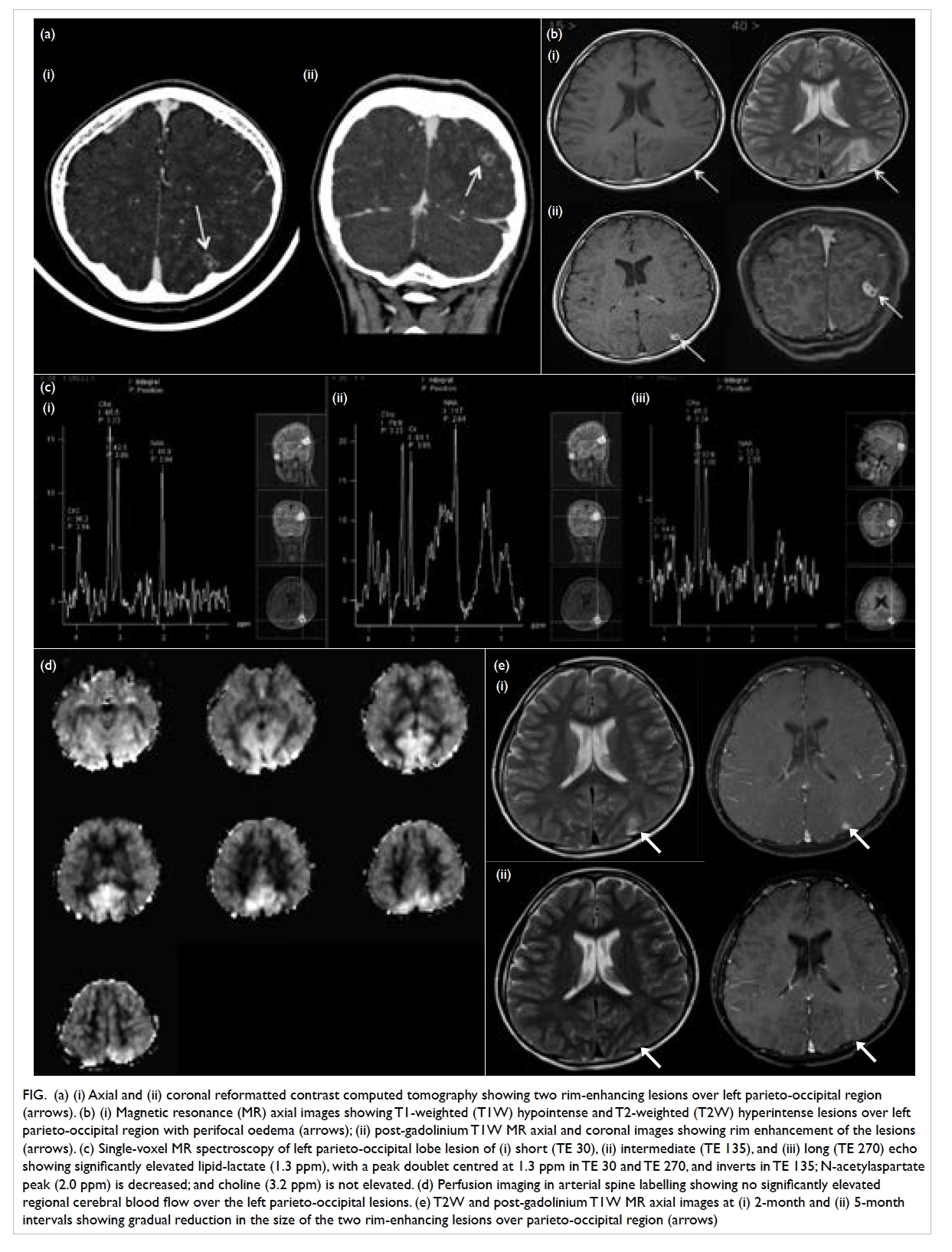

A few international diagnostic criteria for

neurocysticercosis have been proposed, and aim

to stratify the diagnostic strength based on the

interpretation of clinical, radiological, serological,

and epidemiological information. One of the most

widely accepted revised criteria was proposed by

Del Brutto et al in 2001,1 and classifies patients into

two degrees of diagnostic certainty—definitive or

probable. Definitive diagnosis requires the presence

of one absolute criterion or two major plus one minor

epidemiological criteria. Probable diagnosis can be

made if there are one major plus two minor criteria;

one major plus one minor and one epidemiological

criteria; or presence of three minor plus one

epidemiological criteria. Four categories of criteria

based on their diagnostic strength are shown in

Table a.1

The diagnostic dilemma in our index case

was the lack of characteristic imaging features and

positive serological proof, hence difficult differentiation

from tuberculosis infection, i.e. tuberculomas.

Other common differential diagnoses of cystic

lesions include pyogenic abscesses and metastases.

Both were unlikely in our patient given the aseptic

clinical presentation, normal blood and CSF profiles,

absence of a known primary and lack of associated

radiological findings (eg cerebritis, ventriculitis or

meningeal enhancement). Biopsy or excision of the

cerebral cystic lesions might offer a straightforward

histopathological diagnosis, however, it is an invasive

investigation and imposes potential risks.

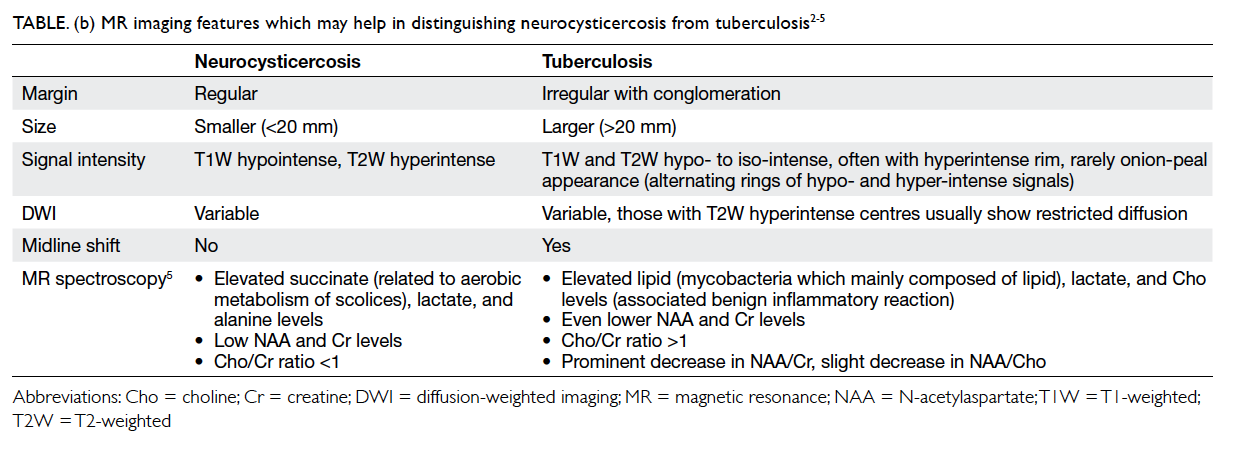

Attempts have been made in the literature

to distinguish cysticercosis and tuberculosis

neurological infection by combined interpretation of

the clinical, radiological, and serological features.2 3 4

Clinically, tuberculomas are more often

associated with increased intracranial pressure and

focal neurological deficits, whereas patients with

neurocysticercosis are usually less symptomatic or

present with seizures.2

Radiologically, the imaging findings of

neurocysticercosis are variable, depending on the

stage and location of infestation. A diagnostic dilemma

lies in those who present with intracranial cystic

lesions without presence of scolex, and that may be

present in both neurocysticercosis and tuberculosis.

Table b shows some MRI imaging features that may

help distinguish the two diagnoses.2 3 4 5

Table (b). MR imaging features which may help in distinguishing neurocysticercosis from tuberculosis2 3 4 5

Based on the neuroimaging features and the

revised diagnostic criteria, a probable diagnosis of

neurocysticercosis was made: presence of lesions

compatible with neurocysticercosis that resolved

after treatment with albendazole, and a history of

travelling to an endemic area.

Neurocysticercosis is an uncommon parasitic

infection of the central nervous system in Hong

Kong and requires a high degree of clinical suspicion

for diagnosis. Despite the advances in neuroimaging,

accurate diagnosis is still sometimes difficult, which

is related to the pleomorphic disease nature and

significant overlapping features with tuberculosis. A

combination of proper interpretation of diagnostic

criteria and imaging findings is helpful in making the

diagnosis without invasive and potentially harmful

investigations.

References

1. Del Brutto OH, Rajshekhar V, White AC Jr, et al. Proposed

diagnostic criteria for neurocysticercosis. Neurology

2001;57:177-83. Crossref

2. Rajshekhar V, Haran RP, Prakash GS, Chandy MJ.

Differentiating solitary small cysticercus granulomas

and tuberculomas in patients with epilepsy. Clinical

and computerized tomographic criteria. J Neurosurg

1993;78:402-7. Crossref

3. Garg RK, Kar AM, Kumar T. Neurocysticercosis like

presentation in a case of CNS tuberculosis. Neurol India

2000;48:260-2.

4. Garg RK. Diagnosis of intracranial tuberculoma. Indian J

Tuberc 1996;43:35-9.

5. Pretell EJ, Martinot C Jr, Garcia HH, Alvarado M, Bustos

JA, Martinot C; Cysticercosis Working Group in Peru.

Differential diagnosis between cerebral tuberculosis and

neurocysticercosis by magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J

Comput Assist Tomogr 2005;29:112-4. Crossref