Hong Kong Med J 2024 Apr;30(2):167–9 | Epub 17 Apr 2024

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Burkholderia pseudomallei pericarditis as a mimicker of tuberculous pericarditis: a case report

Frederick HC Lau, MB, BS; MF Lin, MB, BS, FHKAM (Surgery); WS Ng, MB, BS, FHKAM (Surgery)

Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr Frederick HC Lau (hcf.lau@ha.org.hk)

Introduction

Melioidosis, also known as Whitmore’s disease,

occurs predominantly in tropical climates and

can cause pneumonia, soft tissue infection, brain

abscess, and septicaemia. Very few cases of

melioidosis pericarditis have been reported. The

most common cause of constrictive pericarditis

in Hong Kong is tuberculosis. We report a patient

with melioidosis constrictive pericarditis with

presentation mimicking tuberculous pericarditis

infection in whom we performed pericardiectomy.

Case presentation

A 61-year-old man who was a chronic smoker and

worked on a construction site presented with fever

and heart failure symptoms including dyspnoea,

orthopnoea, and ankle oedema. Laboratory results

showed elevated white blood cell count (21.7 × 109/L)

with neutrophils predominant (19 × 109/L) and raised

levels of C-reactive protein (303 mg/L) and liver

parenchymal enzymes (alanine transaminase level:

153 U/L, alkaline phosphate level: 125 U/L). Repeated

blood cultures were negative. Sputum for acid-fast

bacilli smear and culture and Mycobacterium

tuberculosis polymerase chain reaction were

negative. Computed tomography (CT) with contrast

showed bilateral multiple small lung nodules

(largest 1.3 cm) with mediastinal and right hilar

lymphadenopathy. Transthoracic echocardiogram

revealed bilateral pleural effusion with pericardial

effusion requiring pericardial drain insertion 2 days

after admission. Analysis of pericardial fluid showed

elevated adenosine deaminase (ADA) level (58 U/L)

and culture showed scanty growth of pseudomonal

species after 6 days. No Mycobacterium species was

isolated after 6 weeks of incubation. The patient

was commenced on empiric antituberculosis

treatment (isoniazid 300 mg daily, rifampicin 600 mg

daily, pyrazinamide 1500 mg daily, ethambutol

900 mg daily, and pyridoxine 20 mg daily) 3 weeks

after admission in view of the elevated ADA level,

persistent intermittent fever while on intravenous

piperacillin/tazobactam and due to the risk of

tuberculous pericarditis in Hong Kong. He was discharged and referred to our cardiothoracic centre

for elective pericardial biopsy.

While waiting for our outpatient clinic

assessment, the patient was admitted as an emergency

1 month after commencing antituberculosis

treatment with shortness of breath and frequent

episodes of atrial flutter. He was later transferred

to our cardiothoracic unit for further management.

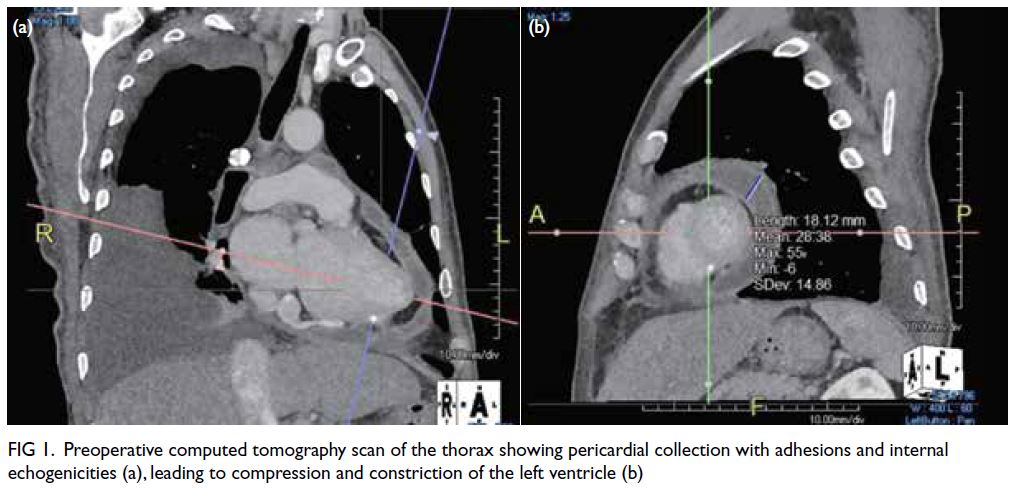

Echocardiogram and CT scan of the thorax showed

a large heterogeneous pericardial collection with

adhesions and internal echogenicities of up to 3.5 cm

in diameter, located next to the left ventricle with

signs of compression and constriction (Fig 1). There

were also signs of septal bounce and exaggerated

respirophasic changes of tricuspid and mitral inflow.

Left and right ventricular systolic function was

reduced due to impaired bi-ventricular contractility

caused by pericardial adhesions and constriction,

confirmed by right heart catheterisation (high

right ventricular end-diastolic pressure–to–right

ventricular systolic pressure ratio, discordance

between left ventricular systolic pressure and right

ventricular systolic pressure during respiration).

Figure 1. Preoperative computed tomography scan of the thorax showing pericardial collection with adhesions and internal echogenicities (a), leading to compression and constriction of the left ventricle (b)

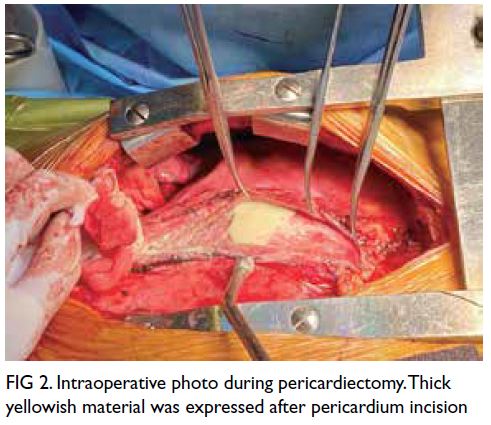

Pericardiectomy was performed and the excised

pericardium sent for sectioning revealed suppurative

granulomatous inflammation (Fig 2). The Ziehl–Neelsen stain and Mycobacterium tuberculosis

polymerase chain reaction were negative. Pericardial

pus aspirate contained Burkholderia pseudomallei species.

Figure 2. Intraoperative photo during pericardiectomy. Thick yellowish material was expressed after pericardium incision

Antituberculosis treatment was withheld and

melioidosis was treated with intravenous meropenem

for 4 weeks and oral co-trimoxazole with doxycycline

as maintenance therapy. The patient’s postoperative

course was uneventful. Postoperative CT of the

thorax at 3 months showed reduced pericardial

effusion, decreased lung consolidation, and reduced

pleural effusion.

Discussion

Melioidosis is caused by intracellular Gram-negative

saprophytic B pseudomallei. This bacterium was

formerly classified in the genus Pseudomonas

but is now separated from Pseudomonas and Stenotrophomonas. It is predominantly found in

contaminated water and soil and spread to humans

through direct contact with contaminated sources.

Melioidosis is a multiorgan infectious disease with

pneumonia as the most common presentation. A

progressive increase in the number of cases has been

observed in Hong Kong over the last 20 years, as

well as in Asia over the past decade.1 There was no

previous reported case of melioidosis pericarditis in

Hong Kong.1

Tuberculosis is caused by the acid-fast bacillus

M tuberculosis. It is airborne and primarily affects

the lungs, and is common in Southeast Asia. The

level of ADA, an enzyme in lymphocytes, increases in the presence of inflammatory effusions caused by

bacterial infection, granulomatous inflammation,

malignancy, and autoimmune disease. It is typically

higher in effusions caused by tuberculosis than

those caused by other conditions with a level

>40 U/L in lymphocyte-predominant effusions

having a sensitivity of 87% to 93% and a specificity

of 89% to 97% for tuberculosis.2 Nonetheless in

neutrophil-predominant effusions, ADA level may

lead to false-positive results since ADA is normally

elevated.2

Constrictive pericarditis is a disease

characterised by pericardial effusion with constrictive

pathology. The most common cause is idiopathic,

followed by tuberculosis, or post-irradiation

and post-pericardiotomy. It is characterised by

echocardiography findings of septal bounce, diastolic

shift of the interventricular septum, restrictive left

ventricular filling pattern, and cardiac catheterisation

finding of square root sign.3

The presentation, laboratory results and

imaging findings are very similar for melioidosis

and tuberculous pericarditis. Most patients have a

subacute-to-chronic disease course. The protein,

sugar and white cell count of pericardial fluid

may also be similar in both diseases. Compared

with patients with tuberculous pericarditis, those

with melioidosis pericarditis more often have a

neutrophil-predominant white blood cell count,4

as in our case. Histological findings can show

granulomatous inflammation with tuberculosis

showing a caseous type.5

It is important to differentiate between B pseudomallei and M tuberculosis and make a correct diagnosis since the treatment for melioidosis pericarditis and tuberculous pericarditis varies

markedly. A prolonged course of intravenous

ceftazidime followed by a combination of co-trimoxazole

and doxycycline is prescribed for

melioidosis while a prolonged course of rifampicin,

ethambutol, pyrazinamide and isoniazid is prescribed

for tuberculosis.3 An incorrect diagnosis not only

delayed treatment for melioidosis in our patient with

consequent worsening of his clinical condition, but

may also have caused more harm by exposing the

patient to the side-effects of tuberculosis treatment.

It is important to send pericardial fluid for culture

and to look meticulously for the two organisms.

Conclusion

The presentation, laboratory results and imaging

findings can be very similar for melioidosis and

tuberculous pericarditis. It is important to bear

this in mind during investigations for chronic

pericarditis and obtain pericardial culture. This will

ensure prompt diagnosis and timely commencement

of appropriate treatment.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept or design, acquisition

of data, analysis or interpretation of data, drafting of the

manuscript, and critical revision of the manuscript for

important intellectual content. All authors had full access to

the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration

of Helsinki and provided informed consent for all treatments

and procedures, and consent for publication.

References

1. Lui G, Tam A, Tso YK, et al. Melioidosis in Hong Kong. Trop Med Infect Dis 2018;3:91. Crossref

2. Chau E, Sarkarati M, Spellberg B. Adenosine deaminase diagnostic testing in pericardial fluid. JAMA 2019;322:163-4. Crossref

3. Chow CY, Lun KS. Idiopathic effusive constrictive

pericarditis in an adolescent boy: a rare cause of heart

failure with diagnostic difficulty. Hong Kong J Paediatr

(new series) 2015;20:110-4.

4. Chetchotisakd P, Anunnatsiri S, Kiatchoosakun S,

Kularbkaew C. Melioidosis pericarditis mimicking

tuberculous pericarditis. Clin Infect Dis 2010;51:e46-9. Crossref

5. Wong KT, Puthucheary SD, Vadivelu J. The histopathology

of human melioidosis. Histopathology 1995;26:51-5. Crossref