Hong Kong Med J 2024 Apr;30(2):164–6 | Epub 11 Apr 2024

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Acute chorioamnionitis following amnioreduction for polyhydramnios in placental chorioangioma complicating pregnancy: a case report

Janice TC Leung, MB, ChB; WY Lok, MSc, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology); William WK To, MD, FRCOG; CW Kong, MSc, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr CW Kong (melizakong@gmail.com)

Case presentation

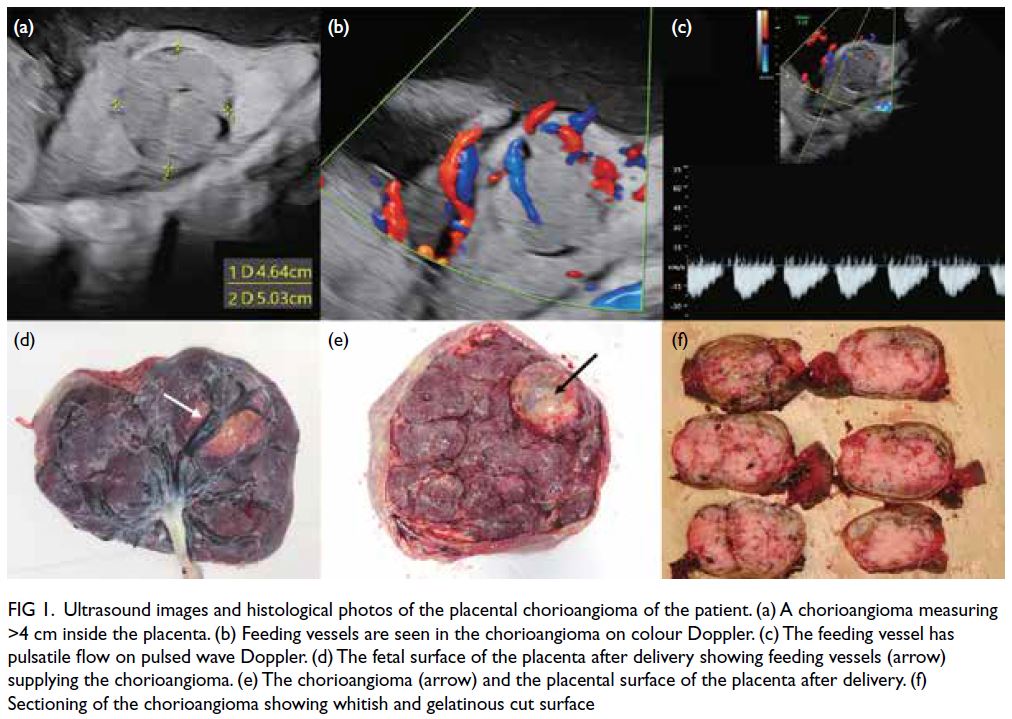

In October 2022, a 29-year-old nulliparous woman at

30 weeks of gestation was found to have a larger-than-dates

uterus with symphysial fundal height of 38 cm.

Her previous antenatal course had been uneventful

with scan at 20 weeks of gestation showing normal

fetal morphology and liquor volume. Ultrasound

revealed polyhydramnios with amniotic fluid index

(AFI) of up to 42 cm but normal fetal growth and

morphology. An echogenic lesion measuring

4.7×5.6×4.5 cm3 was seen in the placenta. The lesion

had feeding vessels visible on colour flow Doppler and pulsatile flow on pulsed wave Doppler (Fig 1).

There were no signs of fetal anaemia or hydrops

fetalis. The diagnosis of placental chorioangioma

was made. A standard 75-g oral glucose tolerance

test was performed due to polyhydramnios and

revealed mild gestational diabetes mellitus with

normal fasting level (4.7 mmol/L) and marginally

raised 2-hour post-loading level of 8.6 mmol/L

(normal range for pregnancy, <8.5).

Figure 1. Ultrasound images and histological photos of the placental chorioangioma of the patient. (a) A chorioangioma measuring >4 cm inside the placenta. (b) Feeding vessels are seen in the chorioangioma on colour Doppler. (c) The feeding vessel has pulsatile flow on pulsed wave Doppler. (d) The fetal surface of the placenta after delivery showing feeding vessels (arrow) supplying the chorioangioma. (e) The chorioangioma (arrow) and the placental surface of the placenta after delivery. (f) Sectioning of the chorioangioma showing whitish and gelatinous cut surface

In view of the severe maternal pressure

symptoms with shortness of breath, amnioreduction

was performed at 31 weeks of gestation under aseptic technique with continuous ultrasound guidance

using a 22-gauge spinal needle connected to low-pressure

wall suction. A total of 2280-mL amniotic

fluid was drained over 3 hours with post-procedure

AFI reduced to 16 cm. In view of the potential risk

of preterm labour, a course of betamethasone (12 mg

every 24 hours for two doses) was administered

intramuscularly prior to amnioreduction to enhance

fetal lung maturity. Results of chromosomal

microarray studies of the amniotic fluid were normal.

One week later, the polyhydramnios recurred with

AFI measuring 40 cm. Amnioreduction was repeated

at 32 weeks of gestation with 2600-mL amniotic

fluid drained over 2.5 hours and AFI reduced to 18

cm. Prophylactic antibiotics were not given prior to

either procedure.

Three days after amnioreduction, the

patient developed signs of sepsis with fever, fetal

tachycardia, and abdominal tenderness. Maternal

white cell count and C-reactive protein level were

elevated. The clinical picture was compatible with acute chorioamnionitis and intravenous antibiotics

were commenced. Emergency caesarean section was

performed and a baby weighing 2080 g was born

with good Apgar score. Septic workup including

blood culture, high vaginal swabs, amniotic fluid and

placental swabs did not yield any bacterial growth.

Both the mother and the baby subsequently recovered

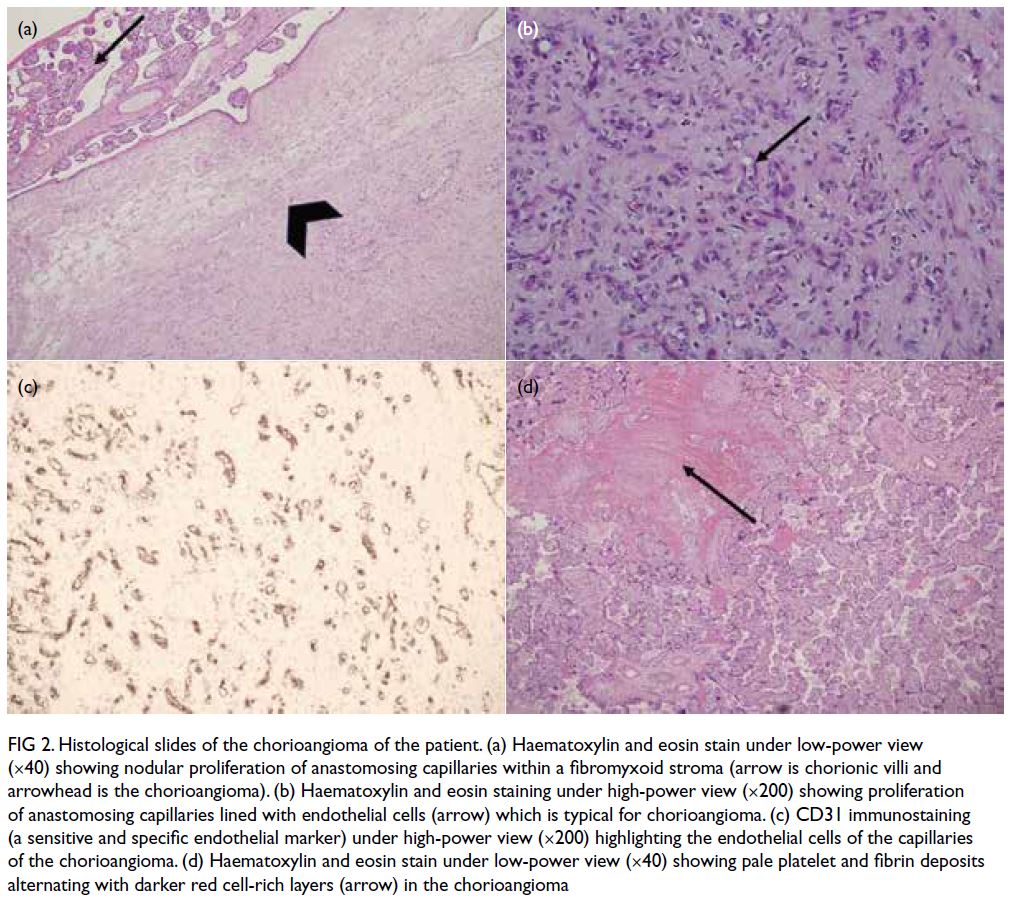

well. Histological examination of the placenta

confirmed the diagnosis of chorioangioma (Fig 2).

Figure 2. Histological slides of the chorioangioma of the patient. (a) Haematoxylin and eosin stain under low-power view (×40) showing nodular proliferation of anastomosing capillaries within a fibromyxoid stroma (arrow is chorionic villi and arrowhead is the chorioangioma). (b) Haematoxylin and eosin staining under high-power view (×200) showing proliferation of anastomosing capillaries lined with endothelial cells (arrow) which is typical for chorioangioma. (c) CD31 immunostaining (a sensitive and specific endothelial marker) under high-power view (×200) highlighting the endothelial cells of the capillaries of the chorioangioma. (d) Haematoxylin and eosin stain under low-power view (×40) showing pale platelet and fibrin deposits alternating with darker red cell-rich layers (arrow) in the chorioangioma

Discussion

There are numerous causes for polyhydramnios in

singleton pregnancies including gestational diabetes,

chromosomal abnormalities, fetal structural

abnormalities such as bowel atresia, and placental

causes such as chorioangioma. As mild gestational

diabetes should not lead to severe polyhydramnios,

the most likely primary diagnosis in our patient

was chorioangioma. The pathophysiology of

polyhydramnios in placental chorioangioma is not completely known. One of the proposed mechanisms

is transudation of fluid from the surface of the

chorioangioma adjacent to the placental surface. The

incidence of placental chorioangioma is estimated to

be around 1%. As chorioangiomas >4 cm can lead to

complications including polyhydramnios, preterm

delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, hydrops

fetalis and even fetal demise, close ultrasound

surveillance, intrauterine interventions or even

early delivery may be necessary.1 Careful ultrasound

examination of the placenta is warranted for all cases

of gross polyhydramnios.

Amnioreduction has been commonly

performed to relieve polyhydramnios in both

singleton and multiple pregnancies. Traditionally,

amniodrainage would be performed using an 18-to 22-gauge spinal needle with the amniotic fluid

removed manually using a three-way tap and 50-mL

syringe. The use of wall suction and a vacuum bottle

aspiration system connected to a needle has been

proposed in recent years to speed up the procedure

and reduce operator fatigue.2

Different complications including preterm

labour, prelabour rupture of membranes and

placental abruption have been reported following

amnioreduction. There is no consensus or guideline

for the most appropriate size of needle or the rate

at which amniotic fluid can be safely removed.

Rapid drainage using an 18- or 20-gauge needle

connected to the vacuum system with the fastest rate

of drainage up to 178 mL/min has been advocated

by Leung et al2 since 2004. The overall complication

rate for this rapid drainage, including placental

abruption, prelabour rupture of membranes and fetal

bradycardia in singleton and multiple pregnancies,

was 3.1%.2 Placental abruption has been reported

following amnioreduction for polyhydramnios

specifically caused by chorioangioma. One patient

has been reported in whom two episodes of

amnioreduction were performed a few days apart

using an 18-gauge needle connected to a vacuum

system.3 With an average drainage rate of 100 mL/min,

2500 mL and 2700 mL of amniotic fluid was removed.

Placental abruption occurred 12 hours after the

second amnioreduction. The authors concluded

that caution should be exercised when performing

large-volume or rapid amnioreductions in idiopathic

or chorioangioma-associated polyhydramnios.3 We

used a small needle (22-gauge) to drain the amniotic

fluid slowly at a rate of 12.7 mL/min in our first

amnioreduction and 17.3 mL/min in the second

amnioreduction in an attempt to lower the risk of

placental abruption and preterm prelabour rupture

of membranes.

Erfani et al4 recently evaluated the

complications following amnioreduction in

singleton pregnancies without other interventions

by combining their findings with those of six other studies. The incidence of preterm labour

was 50.5% (48/95) and that of placental abruption

was 1.3% (4/315), although there was no acute

chorioamnionitis in a total of 244 patients.4 This

implies that the role of prophylactic antibiotics is

dubious. Nonetheless not all studies specified the

duration of the amnioreductions. Only one case of

acute chorioamnionitis following amnioreduction

has been reported.5 That patient had a twin

pregnancy with polyhydramnios not caused by

twin-twin transfusion syndrome. Amnioreduction

was performed at 31 weeks of gestation using an 18-gauge needle with a total of 1950-mL amniotic fluid

removed at a rate of 65 mL/min. She developed acute

chorioamnionitis 18 hours following the procedure.5

Although it is logical to deduce that the risk of

chorioamnionitis will increase with the length of

procedure for amnioreduction, there are no relevant

studies available in the literature to support this

association due to the rarity of this complication.

As far as we are aware, this is the second case

reported in the literature of acute chorioamnionitis

following amnioreduction. As caesarean section was

performed immediately under antibiotic cover when

the patient developed signs of sepsis, the septic

workup did not yield any bacterial growth.

It is crucial to maintain a high index of

suspicion and search for placental chorioangioma

in a fetus where there is no obvious cause for

polyhydramnios to ensure prompt diagnosis and

proper management. Amnioreduction carries risks

of complications, including placental abruption

and acute chorioamnionitis, and the optimal rate of

drainage remains controversial.

Author contributions

Concept or design: JTC Leung, CW Kong.

Acquisition of data: JTC Leung.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: JTC Leung, CW Kong.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: WWK To, CW Kong.

Acquisition of data: JTC Leung.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: JTC Leung, CW Kong.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: WWK To, CW Kong.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr CL Ho from the Department of Pathology of United Christian Hospital for the histological slides of the chorioangioma of the patient.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of

Helsinki. Written consent was obtained from the patient for

publication of this article and the accompanying images.

References

1. Buca D, Iacovella C, Khalil A, et al. Perinatal outcome of

pregnancies complicated by placental chorioangioma:

systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet

Gynecol 2020;55:441-9. Crossref

2. Leung WC, Jouannic JM, Hyett J, Rodeck C, Jauniaux E.

Procedure-related complications of rapid amniodrainage in the treatment of polyhydramnios. Ultrasound Obstet

Gynecol 2004;23:154-8. Crossref

3. Kim A, Economidis MA, Stohl HE. Placental abruption

after amnioreduction for polyhydramnios caused by

chorioangioma. BMJ Case Rep 2018;2018:bcr2017222399. Crossref

4. Erfani H, Diaz-Rodriguez GE, Aalipour S, et al.

Amnioreduction in cases of polyhydramnios: indications

and outcomes in singleton pregnancies without fetal

interventions. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol

2019;241:126-8. Crossref

5. Elliott JP, Sawyer AT, Radin TG, Strong RE. Large-volume

therapeutic amniocentesis in the treatment of hydramnios.

Obstet Gynecol 1994;84:1025-7.