Medical manslaughter in Hong Kong—how, why, and why not

Hong

Kong Med J 2018 Aug;24(4):384–90 | Epub 27 Jul 2018

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj187346

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REVIEW ARTICLE

Medical manslaughter in Hong Kong—how, why, and why not

Gilberto KK Leung, LLM, FHKAM (Surgery)

Department of Surgery, The University of Hong Kong,

Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof Gilberto KK Leung (gilberto@hku.hk)

Abstract

The increasing number of medical

manslaughter cases in recent years raises concerns about the concept of

criminal liability in medical negligence. Contemporary cases in Hong

Kong have also generated debate on whether criminal law intervention is

justified and effective at dealing with substandard medical practices.

This paper examines the legal principles underlying the applicable legal

offence of gross negligence manslaughter and the implications that

recent events may have on patient care and the medical profession. The

author argues that the criminalisation of medical mistakes can have a

detrimental effect on clinical practice and patient welfare. At stake is

the potential for a loss of mutual trust between the medical profession

and the rest of society. Gross negligence manslaughter is an unstable

legal concept, and criminal sanctions should at most be applied to

conscious violations of established rules and standards but not

unintentional errors. As we await the outcomes of ongoing cases in Hong

Kong, there is an urgent need to uphold standards of practice and to

nurture a robust culture of ethical awareness, compassionate care, and

professionalism.

Introduction

Medical manslaughter is involuntary manslaughter by

gross negligence where patient death has resulted from a grossly negligent

(but otherwise lawful) act or omission.1

Although related prosecutions remain uncommon, the emergence of recent

cases in Hong Kong presents an opportunity to reflect upon whether

criminal sanctions are justifiable and effective at dealing with

substandard medical practices. This paper begins with an examination of

the underlying legal principles, followed by a discussion on how the

current direction of travel might impact patient care and the medical

profession.

Gross negligence manslaughter

The applicable legal offence in medical

manslaughter is that of gross negligence manslaughter (GNM).1 As for civil claims in medical negligence, the legal

test to satisfy is that the affected party is owed a duty of care and that

a breach of that duty has occurred and caused the injury at issue.2 In addition, it must be further established in GNM that

the degree of negligence has gone:

“…beyond a mere matter of compensation between

subjects and has showed such disregard for the life and safety of others

as to amount to a crime against the state and conduct deserving

punishment”.3

The legal test was affirmed in the landmark case of

Adomako, in which an anaesthesiologist failed to respond to a

disconnection of the oxygen supply during general anaesthesia, whereby the

jury had to decide whether “the degree of negligence is so great that

a criminal penalty is warranted”.4

It is ultimately about the transformation of a private wrong into a public

one.

Contemporary cases

Medical manslaughter cases have historically been

rare, but a rising trend has been observed in recent years. In the UK, 85

doctors were charged between 1795 and 2005,5

while 11 cases have already materialised between 2006 and 2013.6 A similar situation has occurred in the United States,

where over 50 prosecutions have been brought since 1990.7 The majority of UK cases involved obstetrics and errors

in the prescription or administration of drugs.5

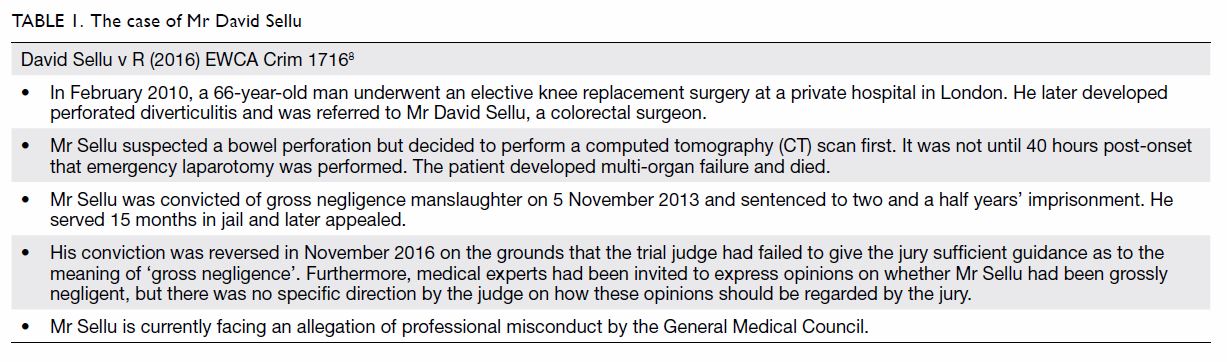

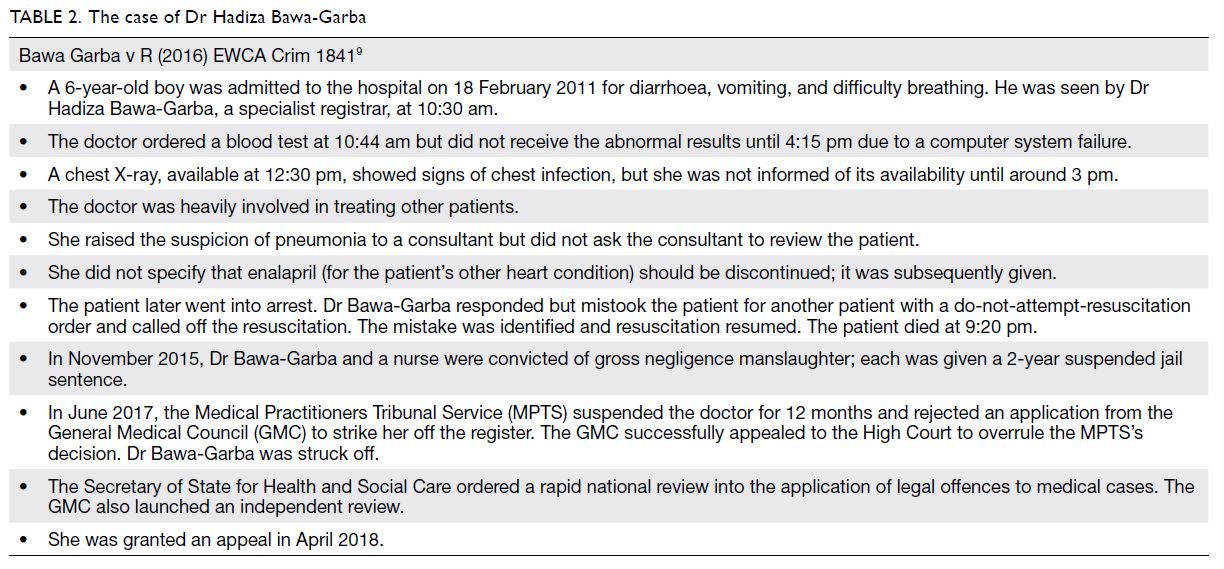

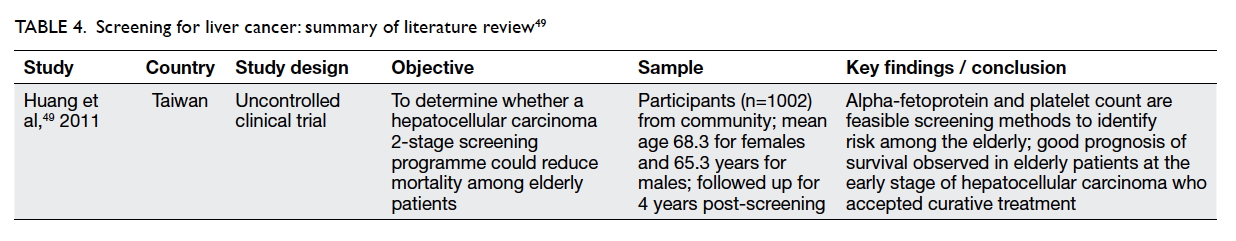

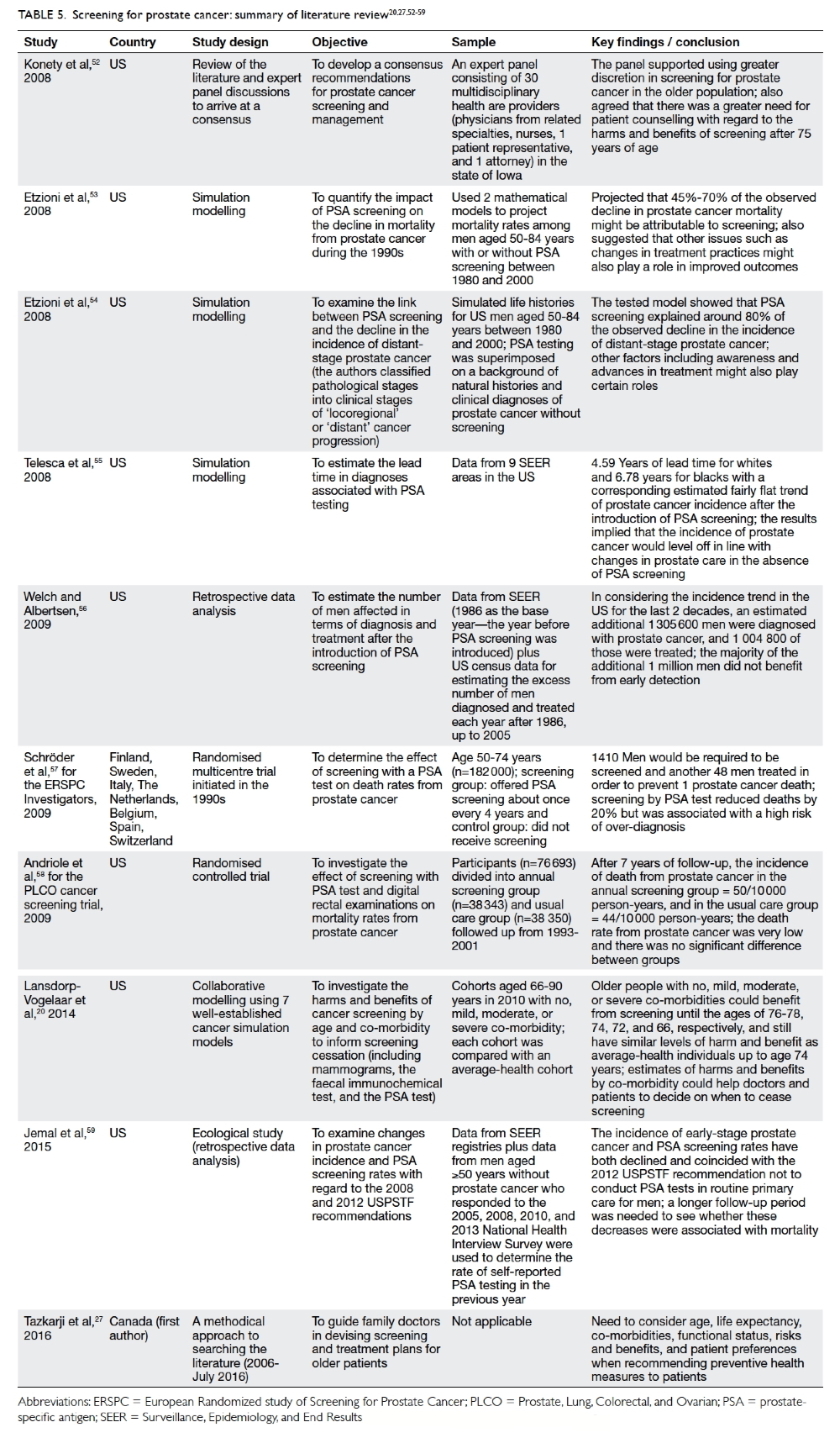

Tables 1 and 2 outline the two recent and controversial cases of

Mr David Sellu8 and Dr Hadiza

Bawa-Garba,9 respectively.

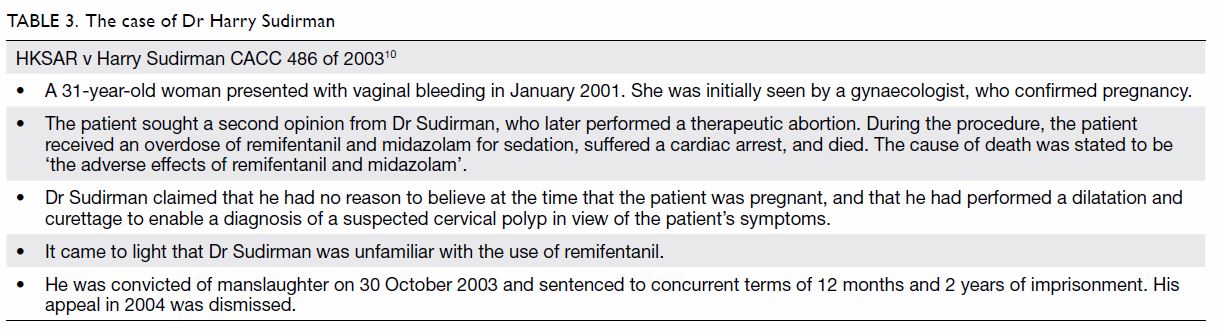

The first case in Hong Kong involved the misuse of

sedative drugs during an illegal abortion for which the doctor was jailed

for 2 years in 2003 (Table 3).10

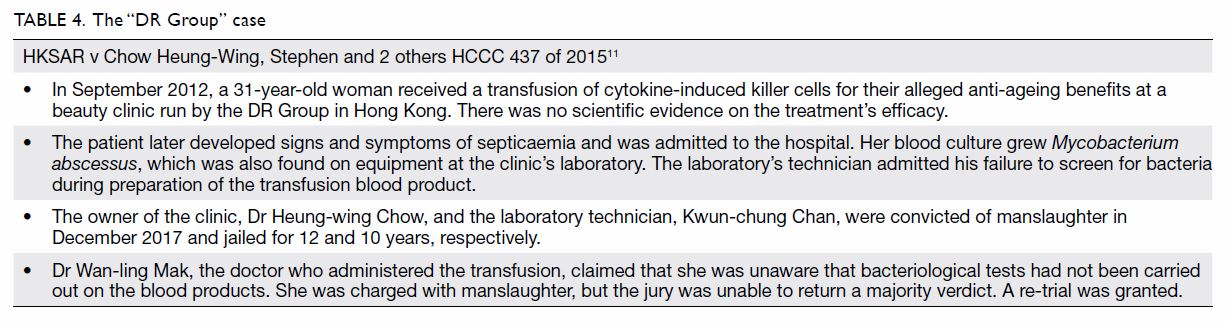

A hiatus followed. The highly publicised “DR Group” case saw the

conviction of a beauty clinic’s owner and technician in 2017; the third

defendant, a doctor who gave the treatment, is awaiting a re-trial (Table

4).11 In March 2018, a

general practitioner was charged after her patient died following a

liposuction 4 years prior.12

Presently, the family of a 73-year-old man is alleging criminal

responsibility on the part of a group of nurses13

and a doctor14 who were already

found guilty of professional misconduct in connection with his death.

Could this be the beginning of a trend in Hong

Kong? If so, what could we be wrestling with here?

Medical negligence as crime

The central and hotly debated question is whether

criminal law intervention is justified in cases of fatal medical

incidents.15 On the one hand, a

doctor’s license to practice has a legal foundation. Criminal sanctions

serve an important punitive function and a symbolic role in restoring

public trust when that foundation is not being respected. By holding

individuals publicly accountable, criminal sanctions may ensure compliance

with professional standards and deter poor and dangerous practices.16 In France, for example, a range of criminal offences

is available to punish medical mistakes, even when they are non-fatal.

Jail terms are uncommon; the ultimate force of deterrence lies in the

stigma of the charge or conviction itself.17

On the other hand, it can be argued that the

criminal law is supposed to punish those who cause damages with a morally

blameworthy state of mind, whereas misjudgement, inadvertence, or sheer

incompetence may be the reasons for a doctor failing to meet standards of

care.18 Criminal sanctions

presume, if not forcibly embed, the role of choice in situations where no

choice or decision has been consciously made. This overlooks the notion of

blameworthiness as the foundation of the criminal law, and prosecutions

were arguably unjustified in at least some cases.19

At issue is the appropriateness of the legal test and the threshold for

prosecution.

The legal test

The term “gross negligence” has not been defined,

and the legal test established in Adomako has been criticised for

its circularity, in that an act or omission constitutes a crime if the

jury finds it a crime.7 The

determination of “grossness” is one for the jury, as directed by the

judge; it is a question of law and not for medical experts to address.

However, medical experts have occasionally employed their varied

understanding of the legal term and provided opinions that could

potentially usurp the jury’s role.20

In the UK, the conviction of Mr David Sellu was reversed because the trial

judge had failed to direct the jury properly with regard to the

determination of “grossness” and the weight given to the expert opinions

on that issue (Table 1).8

Clearer guidance has since become available; how this will affect judicial

practice and outcomes within the UK and other common law jurisdictions,

such as Hong Kong, remains to be discovered.

Another contentious aspect of the existing law

concerns the mens rea (or “guilty mind”) requirement for GNM. A

detailed discussion on this highly complex topic is beyond the scope of

this paper, and readers are referred to previous works by legal scholars.18 21

22 23

It suffices to say that the culpable mental state in GNM is one of

indifference. This can be understood as a state of “wilful blindness” or a

high degree of negligence in considering and avoiding obvious risks.18 It is (arguably) distinguishable from recklessness,

which is acting in the face of subjectively known risks, but less readily

so from what is commonly regarded as “inadvertence” or “absent-mindedness”

by lay people.23

Take for example a hypothetical scenario in which a

patient died from septicaemia following a transfusion procedure. While

those who consciously disregarded standard safety procedures in preparing

the blood product should probably be held criminally liable, it is

debatable whether the doctor who gave the transfusion should be so

treated. Did the doctor know or suspect the risk of contamination? If not,

should he or she have been aware of or considered the possibility of that

risk? Was he or she “indifferent”? What is the level of due diligence

reasonably expected from a doctor administering a treatment passed to him

or her by someone else? How much checking is needed, and how should

“grossness” be determined in a situation like this? And from an ethical

point of view, should the severity of the consequence alone (ie, patient

death) transform a common human failing such as “inattention” into a

crime? If so, what could this mean in daily clinical practice?

There is no ready answer, and the concept of

liability in criminal negligence remains controversial, especially in the

medical context.23 In the UK,

charges against two pharmacists, whose dispensing of a defective medicine

caused a child’s death, were dropped because of the absence of malicious

intent to cause harm,24 whereas

two junior doctors who inadvertently injected vincristine into a patient’s

spine were convicted on the grounds that criminal liability may be found

not at the time of the injection but when they had “chosen” not to be more

careful before acting.25 The

distinction between these individuals’ corresponding mental states is not

overly clear, and the legal bar for gross negligence remains disputable.14

The situation is further complicated by the fact

that a defendant’s mental state may be judged either objectively (ie, what

a reasonably competent doctor should have been thinking at the time) or

subjectively (ie, what the doctor in question was actually thinking at the

time).18 In the sensationalised

case of Dr Conrad Murray, convicted for causing the death of the singer

Michael Jackson, it was sufficient for the prosecution to prove that the

doctor “should have been aware” of the risks associated with using

Propofol outside of a hospital setting, not whether he had actual

knowledge of those risks (ie, an objective test).26

In contrast, the High Court of Hong Kong had consciously departed from the

established English authorities and applied the subjective test in a

recent non-medical case.27 The

debate continues.28

Threshold for prosecution

A charge of GNM even without conviction can be

devastating for the doctor involved. In principle, prosecution is brought

when it is in the public interest to do so and when there is a realistic

prospect of success, but the loosely defined concept of gross negligence

affords prosecutors considerable discretion.29

Importantly, the criteria for distinguishing between honest mistakes and

conscious violations of professional standards are “tests unknown to

the criminal law”.30 As a

result, doctors (or even lawyers) can have little confidence in knowing

what kinds of behaviour will attract the attention of the criminal law.

Indeed, prosecutors in the UK have been criticised

for prosecuting many doctors who should not have been charged in the first

place.19 Such prosecutions have

caused significant disruptions to the personal and professional lives of

innocent individuals and negative feelings within the medical community.31 The small number of cases in

Hong Kong does not permit a valid assessment, but a reasonable,

consistent, and transparent threshold for prosecution would certainly be

welcomed. The principle reaffirmed in Mr David Sellu’s successful appeal

is that a prosecution should not be brought unless the conduct of the

doctor involved was “truly exceptionally bad”. The mere commission

of an error, even if fatal, does not begin to satisfy that test.

Criminal sanctions as a quality assurance measure

From the public’s point of view, an important

question is whether criminalisation improves patient safety. There is no

empirical evidence to show that it does, and the current understanding of

the nature of human error challenges the premise that punishment can

prevent mistakes.32 Again, a

distinction can be made between errors and violations.

Human errors are by nature unintentional. Even the

most able and conscientious clinician can commit errors in a complex

hospital environment; inexperience, exhaustion, lack of supervision, or

systemic failures may be responsible.33

Because errors are committed without awareness of the associated risks,

they are unlikely to respond positively to the threat of criminal

prosecution.34 This is

particularly the case where health care delivery involves multiple

disciplines and professionals whose roles and responsibilities, and hence

their duties of care and liabilities, cannot be easily delineated.

Moreover, human error is often the last part of a chain of events leading

up to an adverse outcome; the proper response should be the adoption of a

culture of open disclosure, learning, risk management, and system

improvement measures.32 A case in

point is that of Dr Bawa-Garba, in which system factors such as

understaffing, lack of supervision, and hardware malfunction are thought

to be at least partially responsible for a tragic patient outcome (Table

2).

In contrast, violations are associated with

deliberate disregard for patient safety and unjustified risk taking.

Adverse outcomes occur primarily because of individual doctors’ autonomous

decisions rather than the cumulative effects of system and latent factors.

The predominance of human agency renders system improvement measures

ineffective if not irrelevant; deterrence targeting individuals’ attitudes

and mental states is needed.22

Criminal sanctions in these situations can potentially discourage some

doctors’ “couldn’t care less” attitude and promote a greater sense of

responsibility and carefulness. The conduct of Dr Sudirman and the two

convicted individuals in the “DR Group” case in Hong Kong fall squarely

into this category (Table 3 and 4).

Admittedly, the distinction between error and

violation is not always straightforward, especially when there are

questions about clinical competency. Clinical competency involves a range

of human qualities, from skills and knowledge to conscientiousness and

ethical standards, only some of which are influenced by threat of criminal

penalties. It is notable that criminal sanctions in the early

vincristine-related cases did not prevent a recurrence: numerous cases

have occurred since.33

Diligence or vengeance?

It has been suggested that the wider use of the

criminal law in the present context represents an attempt by the public to

exact retribution rather than a desire to improve patient safety.35 In the UK, findings from several public inquiries,

such as the Bristol Royal Infirmary Report36

and the Francis Report,37 revealed

widespread unethical and substandard practices within the National Health

Service. Public dissatisfaction and a deepening blame culture have

allegedly created a greater tendency to hold individuals criminally

responsible, turning what was once a private matter of civil litigation

into a public act of criminal prosecution by the state.38

There has at the same time been a gradual but

fundamental shift in the way that the medical profession is perceived by

society.39 Better access to

medical information and a stronger emphasis on patients’ rights means that

doctors are no longer held as high priests of the mysterious art and

science of healing but partners in patient journey or providers of

services to which taxpayers are entitled. Mistakes are not deemed

acceptable simply because medical peers say so; society expects to have

the final word. When society thinks that certain behaviours are

unacceptable, criminal sanctions can be seen as a ready and legitimate

solution.40

The medical profession has not taken this well. In

the UK, the initial conviction of Mr David Sellu was met with fervent

protests.31 This surgeon had an

otherwise unblemished track record, was held in high regard by his peers

and patients, and the penalty imposed on him was seen by some as

unjustifiable and disproportionate (Table 1). Similarly, as mentioned previously, the

court in Dr Bawa-Garba’s case has been strongly criticised for its failure

to give due consideration to system factors.41

The insistence of the General Medical Council on removing Dr Bawa-Garba

from its register caused such an outcry that the UK government decided to

launch a national review into the application of the existing law to

medical cases (Table 2).42

The loss of mutual trust between the medical profession, its regulatory

body and the criminal justice system encapsulated in these cases is

probably the most damaging effect of the prevailing climate of blame and

fear. Patient care may also suffer as doctors become reluctant to disclose

their mistakes. Instead of promoting high-quality care, criminalisation

could in fact encourage the practice of defensive medicine, stifle

compassionate care, alienate the medical profession, and hamper the

promotion of a safety culture.43

The road ahead

Reactions from medical peers in Hong Kong towards

the two convictions in the “DR Group” case have been restrained. Few

appear to condone the negligent practices in that case or disapprove of

the penalties imposed (Table 4). There is arguably a sense of detachment,

as the circumstances in this case (ie, the preparation of an experimental

blood product) are far removed from those commonly experienced by most

doctors. As such, we have not seen the kind of emotional responses from

within our medical sector that have been found in the UK, where doctors

perform routine duties with the knowledge that jail sentences could arise

from a single missed diagnosis or a few hours’ delay in performing

life-saving surgery.

The outcome of the re-trial of the third defendant

in the “DR Group” case could generate more lively discussions for several

reasons. First, general opinions vary more widely regarding the

wrongfulness of the doctor’s conduct. Second, practising clinicians can

relate more readily to the circumstances in this part of the case and see

the relevance and implications of the re-trial. Third, the legal arguments

involved are more complex and subject to debate with respect to the

culpability of the doctor’s mental state.28

Irrespective of the outcome, the ruling will send a strong message on how

similar cases will be handled in the future and raise concerns within

different sectors of society one way or the other. Ahead of us could be a

challenging time.

In the greater scheme of things, there are perhaps

good reasons to believe that the general attitude towards the medical

profession in Hong Kong has not (yet) become hostile, and that the

catalogue of recent cases here is a rare exception. A previous survey

showed that the majority of our patients were very satisfied with the

quality of care received.44 The

number of complaints submitted to the Medical Council of Hong Kong has

remained steady.45 We have not had

any public scandal at a comparable scale to those in the UK, and our

health care professionals still enjoy a reasonable level of respect.44 There is also a handsome degree of transparency and

accountability within our system, while institutional measures are in

place to ensure that our medical students are properly trained, foreign

graduates suitably qualified, and requirements for continuous education

diligently followed.46 47 All of these factors must be acknowledged, treasured,

and enhanced.

But society’s trust in us is not a given; it has to

be earned and maintained. Our doctors and nurses work under challenging

conditions and need to be supported.48

The recent controversy about the suspension of a doctor by the Medical

Council mentioned above represents a serious trust crisis that must be

addressed urgently.14 Meanwhile,

we need to train our medical students and trainees well and impart a

strong sense of ethical awareness and responsibility so that our patients

will remain safe, and know that they are safe, in our hands.49 Public education should culture a better

understanding of the nature of human error and the acknowledgment of the

fact that Medicine is not a perfect science. Lastly, underpinning our

right to practice and power to self-regulate is a social contract with

society that is built on trust.50

The expert opinions we give, how we discuss and handle medical incidents,

and the ways in which we respond to legislative efforts to improve patient

safety will eventually affect how society perceives and reacts to our

mistakes and failings.

Conclusion

The rising number of medical manslaughter charges

and convictions in Hong Kong and overseas poses a concern. Criminal

liability for medical negligence is an arguably unstable legal concept,

and the prosecutorial threshold and legal test for GNM are imbued with

uncertainty. The criminalisation of medical mistakes can potentially

create a climate of blame and fear that is damaging to the medical

profession and detrimental to patient welfare. From the perspectives of

providing deterrence and punishment in the medical context, criminal

sanctions should probably be limited to conscious violations of

established standards; unintentional errors are better dealt with through

professional disciplinary actions or litigation based on the ordinary

civil test of negligence. However, this necessitates a fundamental

jurisprudential shift that is unlikely to materialise in the near future.

As we await the outcomes of ongoing cases in Hong Kong, there is much that

we can do to maintain society’s trust in the medical profession by

upholding standards of care and nurturing a robust culture of

professionalism.

Author contributions

The author has made substantial contributions to

the concept or design; acquisition of data; analysis or interpretation of

data; drafting of the article; and critical revision for important

intellectual content.

Funding/support

This article received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration

The author has disclosed no conflicts of interest.

The author had full access to the data, contributed to the paper, approved

the final version for publication, and takes responsibility for its

accuracy and integrity.

References

1. Crown Prosecution Service, UK

Government. Homicide: murder and manslaughter. Available from:

http://www.cps.gov.uk/legal/h_to_k/homicide_murder_and_manslaughter/#gross.

Accessed 16 Mar 2018.

2. Mason JK, Laurie GT. Mason & McCall

Smith’s Law and Medical Ethics. 9th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press;

2013.

3. R v Bateman [1925] 19 Cr App R 8.

4. R v Adomako [1995] 1 AC 171.

5. Ferner RE, McDowell SE. Doctors charged

with manslaughter in the course of medical practice, 1795-2005: a

literature review. J R Soc Med 2006;99:309-14. Crossref

6. White P. More doctors charged with

manslaughter are being convicted, shows analysis. BMJ 2015;351:h4402. Crossref

7. Quick Q. Medicine, mistakes and

manslaughter: a criminal combination? Cam Law J 2010;69:186-203. Crossref

8. David Sellu v R [2016] EWCA Crim 1716.

9. Bawa Garba v R [2016] EWCA Crim 1841.

10. HKSAR v Harry Sudirman CACC 486/2003.

11. HKSAR v Chow Heung-Wing, Stephen and 2

others HCCC 437/2015.

12. Mok D. Hong Kong doctor arrested on

manslaughter charge over death of dancer after beauty treatment. South

China Morning Post. 2018 Mar 13. Available from:

http://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/law-crime/article/2137050/hong-kong-doctor-arrested-manslaughter-charge-over-death.

Accessed

19 Mar 2018.

13. Tsang E. Hong Kong nurses found guilty

of misconduct in fatal blunder or one month. South China Morning Post.

2016 June 13. Available from:

http://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/health-environment/article/1974286/hong-kong-nurses-found-guilty-misconduct-fatal.

Accessed 16 Mar 2018.

14. Cheung E. Hong Kong doctor Wong

Cheuk-yi banned for six months over death of elderly cancer patient Wang

Keng-kao at Kowloon Hospital. South China Morning Post. 2018 May 9.

Available from:

http://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/health-environment/article/2145352/hong-kong-doctor-wong-cheuk-yi-found-guilty.

Accessed 10 Mar 2018.

15. Edwards S. Medical manslaughter: a

recent history. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2014;96:118-9. Crossref

16. Dekker SA. Criminalization of medical

error: who draws the line? ANZ J Surg 2007;77:831-7. Crossref

17. Spencer JR, Brajeux MA. Criminal

liability for negligence—a lesson from across the Channel? Int Comp Law

Quart 2010;59:1-24. Crossref

18. McCall Smith A. Criminal negligence

and the incompetent doctor. Med Law Rev 1993;1:336-49. Crossref

19. Hubbeling D. Criminal prosecution for

medical manslaughter. J R Soc Med 2010;103:216-8. Crossref

20. Quick O. Expert evidence and medical

manslaughter: vagueness in action. J Law Soc 2011;38:496-518. Crossref

21. Virgo G. Reconstructing manslaughter

on defective foundations. Cam Law J 1995;54:14-6. Crossref

22. Horder J. Gross negligence and

criminal culpability. U Toronto Law J 1997;47:495-521. Crossref

23. Smith AM. Criminal or merely human?:

the prosecution of negligent doctors. J Cont Health Law Policy

1996;12:131-46.

24. March PJ. Boots pharmacist and trainee

cleared of baby’s manslaughter, but fined for dispensing a defective

medicine. Pharmaceutical J 2000;264:390-2.

25. R v Prentice, R v Adomako [1995] 1 AC

171.

26. Kim CJ. The trial of Conrad Murray:

prosecuting physicians for criminally negligent over-prescription. Am Crim

Law Rev 2014;51:517-40.

27. HKSAR v Lai Shui Yin HCCC 29/2011.

28. Leung JA, Liu HT. Gross negligence

manslaughter after Lai Shui Yin. Hong Kong Law J 2014;44:709-17.

29. Quick O. Prosecuting ‘gross’ medical

negligence: manslaughter, discretion, and the crown prosecution service. J

Law Soc 2006;33:421-50. Crossref

30. O’Doherty S. Doctors and

manslaughter—response from the Crown Prosecution Service. J R Soc Med

2006;99:544. Crossref

31. McDonald P. Doctors and manslaughter.

Bull R Coll Surgeons 2014;96:112-3. Crossref

32. Reason J. Human error: models and

management. BMJ 2000;320:768-70. Crossref

33. Leape LL. Error in medicine. JAMA

1994;272:1851-7. Crossref

34. Merry AF. How does the law recognize

and deal with medical errors? J R Soc Med 2009;102:265-71. Crossref

35. Holbrook J. The criminalisation of

fatal medical mistakes. BMJ 2003;327:1118-9. Crossref

36. Department of Health, UK Government.

Learning from Bristol: The Department of Health’s response to the report

of the Public Inquiry into Children’s Heart Surgery at the Bristol Royal

Infirmary 1984-1995. 2002. Available from:

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/273320/5363.pdf.

Accessed 18 Feb 2018.

37. UK Government Report of the Mid

Staffordshire NHS foundation trust public inquiry. London: The Stationery

Office; 2013.

38. Radhakrishna S. Culture of blame in

the National Health Service; consequences and solutions. Br J Anaesth

2015;115:653-5. Crossref

39. Edwards N, Komacki MJ, Silversin J.

Unhappy doctors: what are the causes and what can be done? BMJ

2002;324:835-8. Crossref

40. Leung GK. If we do not take charge of

ourselves, some else would (have to). Surg Pract 2016;20:141. CrossRef

41. Cohen D. Back to blame: the Bawa-Garba

case and the patient safety agenda. BMJ 2017;359:j5534. Crossref

42. Donnelly L. Hunt orders review of

medical malpractice amid doctors’ outcry over manslaughter case. The

Telegraph. 6 Feb 2018. Available from:

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2018/02/06/hunt-orders-review-medical-malpractice-amid-doctors-outcry-manslaughter/.

Accessed 26 Mar 2018.

43. Kessler D, McClellan M. Do doctors

practice defensive medicine? Q J Econ 1996;111:353-90. Crossref

44. Wong EL, Coulter A, Cheung AW, Yam CH,

Yeoh EK, Griffiths SM. Patient experiences with public hospital care:

first benchmark survey in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2012;18:371-80.

45. The Medical Council of Hong Kong.

Annual reports 2016. Available from:

https://www.mchk.org.hk/files/annual/files/2016/MCAR_2016_e.pdf. Accessed

26 Mar 2018.

46. The Medical Council of Hong Kong. Hong

Kong doctors. October 2017. Available from:

https://www.mchk.org.hk/english/publications/files/HKDoctors.pdf. Accessed

29 Mar 2018.

47. The Hong Kong Academy of Medicine.

Positional paper on postgraduate medical education. 2010. Available from:

https://www.hkam.org.hk/publications/HKAM_position_paper.pdf. Accessed 27

Mar 2018.

48. Chow CB. Satisfied patients, burnout

doctors! Hong Kong Med J 2012;18:360-1.

49. Wong DS, Lai PB. Malpractice claims:

prevention is often a better strategy. Hong Kong Med J 2011;17:425-6.

50. Cruess SR, Cruess RL. Professionalism:

a contract between medicine and society. CMAJ 2000;162:668-9.