Congenital infections in Hong Kong: an overview of TORCH

Hong Kong Med J 2020 Apr;26(2):127–38 | Epub 2 Apr 2020

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REVIEW ARTICLE CME

Congenital infections in Hong Kong: an overview

of TORCH

Karen KY Leung, MB, BS, MRCPCH1; KL Hon, MB, BS, MD1; Alice Yeung2; Alexander KC Leung, FRCP (UK), FRCPCH3; Elim Man, MB, BS, MRCPCH1

1 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, The Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Kowloon Bay, Hong Kong

2 Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

3 Department of Pediatrics, University of Calgary and Alberta Children’s Hospital, Calgary, Canada

Corresponding author: Dr KL Hon (ehon@hotmail.com)

Abstract

Congenital infections refer to a group of

perinatal infections that may have similar clinical presentations, including rash and ocular findings. TORCH is the acronym that covers these infections (toxoplasmosis, other [syphilis], rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus). There are, however, other important causes of intrauterine/perinatal infections, including enteroviruses, varicella zoster virus, Zika virus, and parvovirus B19. Intrauterine and perinatal infections are significant causes of fetal and neonatal mortality and important contributors to childhood morbidity. A high index of suspicion for congenital infections and awareness of the prominent features of the most common congenital infections can help to facilitate early diagnosis, tailor appropriate diagnostic evaluation, and if appropriate, initiate early treatments. In the absence of maternal laboratory results diagnostic of intrauterine infections, congenital infections should be suspected in newborns with certain clinical features or combinations of clinical features, including hydrops fetalis, microcephaly, seizures, cataract, hearing loss, congenital heart disease, hepatosplenomegaly, jaundice, or rash. Primary prevention of maternal infections during pregnancy is the cornerstone of prevention of congenital infection. Available resources should focus on the promotion of public health.

Introduction

Congenital infections are those that can cross the

placenta and damage the fetus in utero or transmit

to the infant during the peripartum period of

birth, resulting in neonatal infection.1 Apart from

miscarriage, stillbirths, and neonatal deaths,

congenital infections account for 2% to 3% of all

congenital anomalies and are a significant cause

of childhood morbidity.2 3 4 Immunologist Andres

Nahmias first used the acronym ToRCH in 1971

to describe perinatal infections associated with

toxoplasma (To), rubella (R), cytomegalovirus (C),

and herpes simplex virus (H); these infections are

difficult to differentiate from one another clinically.5

In 1975, Harold Fuerst proposed adding syphilis,

another important congenital infection, to the list and

revising the acronym into STORCH.6 Also in 1975,

Roger Brumback recommended replacing STORCH

with TORCHES, as the latter term was more readily

accepted and recognised by paediatricians familiar

with the older acronym.7 Subsequently, the ‘O’ in

TORCH has been broadened and now stands for

‘Others’ to include the following pathogens: syphilis,

parvovirus, coxsackievirus, listeriosis, hepatitis

virus, varicella-zoster virus, Trypanosoma cruzi, enterovirus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV),

and the latest addition, Zika virus.1 4

Congenital infections have remained a major

public health issue globally, especially in developing

countries. These infections can lead to significant

consequences, such as severe disabilities or even

fetal deaths, but most of them are preventable

by preventing primary maternal infection during

pregnancy. In view of this, public awareness is crucial.

The World Health Organization has proposed

strategies to eliminate mother-to-child transmission

of HIV by 2020 and syphilis and hepatitis B by 2030.8

This review discusses congenital infections

in terms of the clinical features, medical

management, implications to public health, and

neurodevelopmental outcomes pertinent to the

local situation. This review will focus on the classic

TORCH infections: toxoplasmosis, syphilis, rubella,

cytomegalovirus (CMV), and herpes simplex virus

(HSV). References were searched using key terms

‘congenital infection’ and ‘Hong Kong’ or ‘TORCH’

and ‘Hong Kong’ in PubMed, limited to ‘human’,

with no filters on article type or publication date.

Discussion is based on, but not limited to, the search

results.

T – Congenital toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasma gondii is the protozoan parasite

responsible for congenital toxoplasmosis.

Toxoplasma infection usually occurs through

contact with faeces of infected cats or consumption

of raw or undercooked meat, raw oysters, clams,

mussels, fruits, vegetables, goat’s milk, or water

contaminated with the parasite.9 Approximately 30%

of primary Toxoplasma infections during pregnancy

result in vertical transmission to the fetus through

the transplacental route.9 10 Congenital infection

occurs predominantly after primary infection

during the parasitemic phase in a pregnant woman.

However, cases of transmission from women

infected shortly before pregnancy and reactivation

from immunosuppressed women have also been

reported.11 The sequelae tend to be more frequent

and severe if the mother is infected during the first

or second trimester of pregnancy, which may result

in intrauterine death, spontaneous abortion, or

premature birth.11 The risk of developing the classic

triad of congenital toxoplasmosis (intracranial

calcifications, hydrocephalus, and chorioretinitis)

decreases from 61% at 13 weeks to 25% at 26

weeks and 9% at 36 weeks. However, if maternal

infection occurs later during gestation, the risk of

transmission to the fetus is higher, increasing sharply

from 6% at 13 weeks to 40% at 26 weeks and 72% at

36 weeks.10 12

The seroprevalence of toxoplasmosis also

varies greatly by geographical area, ranging from

less than 1% to more than 95%. The highest rates

are found in Latin American countries while the

lowest rates are reported in the Southeast Asia.9 In

1980, the overall seroprevalence of toxoplasmosis in Hong Kong was reported to be 9.8%; this low rate is

probably attributed to the local habit of eating well-cooked

meat as part of traditional Chinese meals

and the relatively low number of households that

keep cats as pets.13 The estimated global incidence

of congenital toxoplasmosis is approximately

190 100 cases annually, with an incidence rate of

approximately 1.5 cases per 1000 live births.14

Although congenital toxoplasmosis is

asymptomatic in approximately 75% of affected

newborns, common manifestations in symptomatic

neonates include fever, maculopapular rash,

chorioretinitis, intracranial calcification,

hydrocephalus, abnormal cerebrospinal fluid

(CSF), jaundice, thrombocytopenia, anaemia,

hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, pneumonitis,

seizures, microphthalmia, and microcephaly.10 15 The

classic triad of chorioretinitis, hydrocephalus, and

intracranial calcifications occur in less than 10% of

cases of congenital toxoplasmosis.16 Infants who are

asymptomatic at birth may develop chorioretinitis,

blindness, cerebral palsy, cerebellar dysfunction,

microcephaly, seizures, mental retardation,

sensorineural deafness, or growth retardation later

in life, and untreated cases are at higher risk of

developing these serious sequelae.17 18

Acute maternal infection with T gondii is

usually asymptomatic. Symptoms include transient,

mild fever, headaches, myalgias, maculopapular rash,

sore throat, lymphadenopathy, and hepatomegaly.

When toxoplasmosis is suspected, three tests can

be performed for prenatal diagnosis. Serological

tests to detect the levels of Toxoplasma-specific

immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM antibodies in the

maternal serum are widely used to assess immunity

to the parasite and any recent infection in the

pregnant mother. After infection, IgG appears in 1

to 2 weeks and persists throughout life, therefore

leading to immunity in the mother. In contrast,

IgM becomes detectable earlier after infection than

IgG and persists for a variable period from months

to years, such that positive results for both IgG

and IgM antibodies can be difficult to interpret.9

Ultrasonography of affected fetuses can be normal

or non-specific, but intracranial calcifications,

ventricular dilatations, hepatic enlargement,

ascites, and increased placental thickness are

present in approximately 6% of infected fetuses.19 20

Because maternal infection does not necessarily

result in fetal infection, suspected or established

maternal infection should be confirmed prenatally

by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification

of Toxoplasma DNA in amniotic fluid. Diagnostic

performance after 18 weeks of gestation and at least

4 weeks after maternal seroconversion is likely to be

more reliable.10 21

Postnatal diagnosis of congenital toxoplasmosis

can be confirmed by detection of T gondii in the infant’s umbilical cord blood, urine, peripheral

blood, or CSF; Toxoplasma DNA in the infant’s

amniotic fluid, peripheral blood, urine, or CSF;

IgG, IgM, and IgA antibodies in peripheral blood

or CSF; or Toxoplasma IgG antibody at 12 months

of life. For infants positive for IgG but negative for

IgM and IgA, follow-up serology testing for IgG

should be repeated every 4 to 6 weeks until complete

disappearance of IgG.9 21 22

When primary maternal infection is diagnosed

before 18 weeks of gestation, antiparasitic treatment

with spiramycin should be initiated as soon as

possible to prevent transplacental transmission.9 10

If PCR on amniotic fluid is positive for T gondii

DNA after 18 weeks of gestation, treatment

should be replaced by pyrimethamine-sulfadiazine

with leucovorin (folinic acid). If PCR is negative,

following the prophylaxis regimen in the US and

France, continuation of spiramycin is recommended

until delivery; or following the prophylaxis regimen

in Austria and Germany, spiramycin is used by a

4-week course of pyrimethamine-sulfadiazine at 17

weeks of gestation.10

For infants with symptomatic congenital

toxoplasmosis, a 12-month treatment with

pyrimethamine-sulfadiazine is indicated. Folinic

acid is also given to minimise pyrimethamine

toxicity.10 22 As sulfadiazine is not available in Hong

Kong, clindamycin can be used instead.23 The same

regimen is used for asymptomatic infants, but the

treatment duration is 3 months.22

Education on prevention of Toxoplasma

infection is important for pregnant mothers.

They should be advised to avoid eating raw or

undercooked meat/shellfish or drinking unfiltered

water; to clean fruits and vegetables thoroughly

before consumption24; and to employ proper hand

hygiene to reduce the risk of infection.25 If the family

keeps cats as pets, the cats should not be fed raw or

undercooked meat and contact with cat litter should

be avoided.26

Universal screening for maternal

toxoplasmosis is incorporated into the maternal-child

care programme in some countries, including

Austria, France, and Italy.27 However, such screening

is not practised in the US, Canada, or the United

Kingdom, mainly because of the lower prevalence of

toxoplasmosis, uncertainty about the effectiveness

of maternal treatment at preventing congenital

infection, high cost of frequent testing required

for early detection of infections, low screening

sensitivity, cost-ineffectiveness of treating women

with false positive results, and possible low

adherence to frequent rescreening.28 29 In Hong

Kong, as the prevalence of toxoplasmosis and the cost

effectiveness of antenatal screening for toxoplasmosis

are relatively low, patient education for prevention of Toxoplasma infection should be sufficient to reduce

the risk of congenital toxoplasmosis.

O – Congenital syphilis

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted disease caused by Treponema pallidum, a spirochete. Congenital

syphilis affects approximately 2 million pregnancies

annually, and approximately 25% of these pregnancies

result in spontaneous abortion or stillbirths.30

Syphilis is not a notifiable disease in Hong

Kong. The Social Hygiene Service reported only 100

new cases in 1991, increasing to 1095 cases in 2018,

accounting for 14.6 cases per 100 000 population.31

This is much higher than the 9.5 cases per 100 000

population reported in the US in 2017.32 In Hong

Kong, congenital syphilis decreased from over

100 new cases annually in the early 1970s to three

cases of congenital syphilis in 2017, 0 cases in 2018,

and one case in 2019 (through August). All recent

reported cases were late congenital syphilis.31

Congenital syphilis usually results from

transplacental transmission of T pallidum, mostly

in untreated or inadequately treated mothers,

especially with concomitant HIV infection. The

risk of fetal infection increases along with the

progression of gestation.9 In contrast, the risk of

vertical transmission in untreated mothers is highest

during the first stage and lowest in the late stage.33

Congenital syphilis can result in spontaneous

abortion (usually after the first trimester), stillbirth,

premature birth, impaired fetal growth, and neonatal

mortality.9,34 Approximately two thirds of infected

neonates born alive are asymptomatic at birth.9 34

However, symptoms usually develop by the third

month if these infants are left untreated.35

Congenital syphilis can be divided into two

stages: early congenital syphilis with symptoms onset

during the first 2 years of life and late congenital

syphilis with manifestations after age 2 years.35

Hepatomegaly with or without splenomegaly,

jaundice, syphilitic rhinitis (snuffles), maculopapular

and vesicular rash, generalised lymphadenopathy,

osteochondritis, and periostitis are common

manifestations of early congenital syphilis.9 36 Other

manifestations of early congenital syphilis include

non-immune hydrops fetalis, fever, pneumonia,

secondary sepsis, myocarditis, inability to move

an extremity because of pain (“pseudoparalysis of

Parrot”), chorioretinitis, cataract, glaucoma, loss

of eyebrows, uveitis, nephrotic syndrome, rectal

bleeding from ileitis, malabsorption, keratoderma of

the hands and feet, and onychauxis of the fingernails

and toenails.37 38 39 Laboratory abnormalities may

include anaemia, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia,

and leukocytosis. Radiological abnormalities may

include erosions (osseous destruction) and lucencies

(demineralisation) of the proximal medial tibial metaphysis (Wimberger sign), metaphyseal lucent

bands, metaphyseal serrated appearance at the

epiphyseal margin of long bones (Wegner sign),

irregular areas of increased density and rarefaction

(‘moth-eaten’ appearance), diaphyseal periostitis,

and multiple sites of osteochondritis.40

Late congenital syphilis occurs in

approximately 40% of untreated infants and is often

related to scarring and deformities resulting from

early infection.9 Manifestations include saddle nose;

perioral fissures (rhagades); frontal bossing; Clutton

joints (symmetrical, sterile, and painless synovial

effusions); thickening of sternoclavicular joint

(Higoumenakis sign); scaphoid scapula; anterior

bowing of shins (saber shins); perforation of the hard

palate; multicusped first molars (mulberry molars);

peg-shaped, notched, widely spaced permanent

upper central incisors (Hutchinson’s teeth);

interstitial keratitis; glaucoma; mental retardation;

sensorineural deafness; and hydrocephalus.9 36 37

Hutchinson’s triad, including Hutchinson’s teeth,

interstitial keratitis, and sensorineural deafness,

specific to late congenital syphilis, is rather rare.36

Diagnosis of gestational syphilis can be

established by serological tests, including both non-treponemal

(rapid plasma regain [RPR] and venereal

disease research laboratory [VDRL]) and treponemal

tests (T pallidum particle agglutination and

automated treponemal assay, eg enzyme immunoassay). Non-treponemal

assays are recommended for screening, followed by

a treponemal test if the screening result is positive. If

the reverse sequence screening algorithm is used and

the pregnant woman is reactive to the treponemal

test, confirmatory testing with a non-treponemal test

should be performed. However, if these two results

are discordant, a different treponemal test using a

different T pallidum should be performed.22 Nonspecific

ultrasonographic abnormalities include

hepatomegaly, placentomegaly, polyhydramnios,

and hydrops fetalis.36 Congenital syphilis should be

suspected in infants with a history of untreated or

inadequately treated maternal syphilis, especially

when they have a reactive treponemal test, and the

physical examination showing signs of infection,

abnormal long bone radiography, elevated cell count,

protein in the CSF, or a quantitative non-treponemal

test with titre at least four-fold higher than that of

the mother. Diagnosis can be established by the

presence of T pallidum in body fluids or samples

from lesions when viewed by dark-field microscopy

or fluorescent antibody staining.41

Parenterally administered penicillin G is the

standard treatment for syphilis.41 Pregnant patients

with immediate-type penicillin allergy should be

treated with penicillin after desensitisation because

there is no satisfactory alternative for treating

syphilis in pregnancy.41 The overall success rate

of maternal treatment at all gestational ages in preventing congenital syphilis is as high as 98% and

maternal secondary syphilis has the highest risk of

fetal treatment failure compared with other stages

of maternal infection.42 Mother-to-child infection is

more likely to occur in adequately treated mothers

in the conditions that the interval from treatment

to delivery is short (<30 days), stage of maternal

infection is early, delivery occurs before 36 weeks

of gestation, or non-treponemal titre is high at the

initiation of treatment and delivery.43

If congenital syphilis is diagnosed or suspected

in an infant, treatment can be made with reference

to the mother’s treatment history for syphilis, the

infant’s physical examination findings, and maternal

and infant RPR/VDRL titres. For proven or highly

probable congenital syphilis, penicillin G should

be given intravenously for 10 days.22 41 For possible

congenital syphilis cases with either incomplete or

abnormal evaluations, the same regimen should be

administered. In cases where congenital syphilis is

less likely positive (eg, infant RPR/VDRL are less than

four-fold of the maternal RPR/VDRL), the infant

should be followed-up every 3 months until nontreponemal

tests become non-reactive; alternatively,

a single dose of penicillin G can be given.22

Screening for syphilis during early pregnancy

remains an important preventive measure against

congenital syphilis since early diagnosis facilitates

timely treatment that can prevent perinatal loss and

potential severe disabilities.44 In Hong Kong and

many other countries, the VDRL test for syphilis is

performed during the first antenatal visit.

R – Congenital rubella

Rubella, also known as German measles, is a viral illness that is often mild or even asymptomatic when

acquired. However, catastrophic consequences may

result from congenital infections and is therefore of

particular concern in pregnant women.

Rubella has been a notifiable disease in Hong

Kong since 1994, and the number of cases has

fluctuated drastically, from eight cases in 1994 up

to 4958 cases in 1997.45 After a spike of 2338 cases

recorded in 2000, the number of rubella cases has

decreased and remained low in recent years. There

were 11 reported cases in 2018 and 46 cases in

2019 (through August).46 From 2001 to 2019, there

were only four reported cases of congenital rubella

syndrome (CRS): one in 2008 and three in 2012.46 The

three cases in 2012 were mothers born in mainland

China who had either uncertain proof or no history

of rubella vaccination.45

Although rubella virus can spread by a

respiratory route, vertical transmission from

an infected mother to her fetus can occur via

haematogenous spread during maternal viraemia.

The risk of transmission differs depending on the

timing of maternal infection.47 A study conducted in England from 1976 to 1978 found that when

maternal infection occurred within the first 12

weeks of gestation, the fetal infection rate reached

>80%; at the end of second trimester, it could drop to

25%; at 27 to 30 weeks, it could be 35%; and when it

occurred during the last month of gestation, the rate

could get close to 100%.48

Rubella infection has an incubation period

of 14 to 21 days and can be asymptomatic (ie,

subclinical) in 25% to 50% of individuals.49 When

symptoms occur, they are usually mild and self-limiting.

Prodromal symptoms include low-grade

fever, malaise, anorexia, nausea, non-exudative

conjunctivitis, coryza, cough, sore throat, headache,

petechiae on the soft palate (Forchheimer spots) and

postauricular area, and occipital and/or posterior

cervical lymphadenopathy.47 49 These symptoms,

though common in adolescents and adults, are

unusual in children.47 Prodromal symptoms are

usually followed by the characteristic pinpoint,

erythematous, maculopapular rash in 50% to 80%

of cases, starting on the face, later spreading to the

trunk and limbs, and becoming generalised within 24

hours.47 The rash usually subsides in 3 days and fades

in the same directional pattern as it appears. Some

individuals, mostly adolescents and adult women,

may also experience polyarthritis and polyarthralgia

approximately 1 week after the rash.49

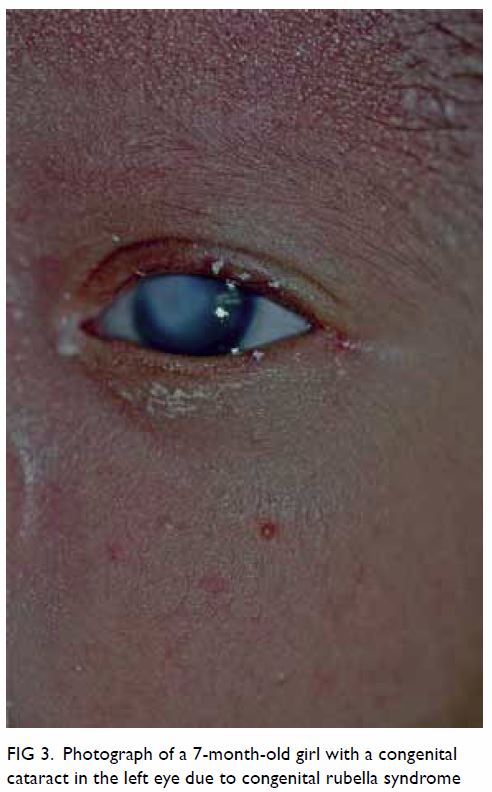

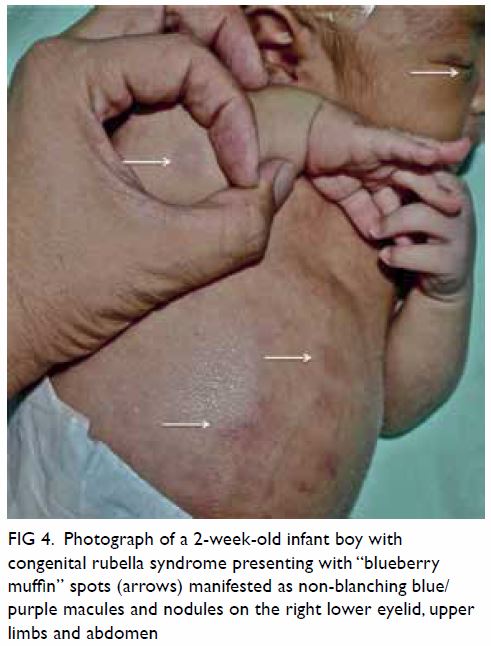

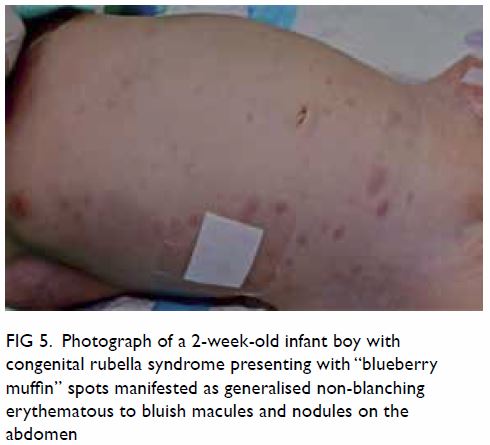

Maternal rubella infection during the first 8

to 10 weeks of gestation can lead to catastrophic

consequences, including spontaneous abortion,

stillbirth, and prematurity.9 50 51 Cataracts,

congenital heart defects (eg, patent ductus

arteriosus, branch pulmonary artery hypoplasia/stenosis), and sensorineural hearing loss are the

classic triad of CRS.47 Other manifestations of

CRS include intrauterine growth retardation,

retinopathy, infantile glaucoma, mental retardation,

microcephaly, meningoencephalitis, hepatitis,

hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, haemolytic anaemia,

thrombocytopenia, and purpura (“blueberry muffin

spots”).9 50 51 52 Some of these clinical manifestations

are transient and non-specific; others may evolve

over time into adulthood, even when the infection

is subclinical at birth.9 50 51 52 The risk of congenital

defects after maternal infection is essentially limited

to the first 16 weeks of gestation. Beyond 20 weeks

of gestation, focal growth restriction seems to be the

only significant sequela.49

Diagnosis of maternal infection can be

confirmed by using serological tests when there

is a four-fold increase in rubella-specific IgG titre

between acute and convalescent serum samples,

a positive test for rubella-specific IgM antibodies,

or a positive culture for the rubella virus.49 Fetal

infection can be confirmed with a positive PCR

assay on a chorionic villus sample when other

clinical findings are consistent with the features of congenital rubella.49 If congenital rubella infection

is suspected, the diagnosis can be confirmed by

the presence of rubella-specific IgM antibodies in

the cord blood or neonatal serum within the first

6 months of life, detection of rubella virus RNA by

reverse transcription PCR on nasopharyngeal swab

or urine, or isolation of the rubella virus.47 53

No specific antiviral treatment for rubella is

now available. When maternal rubella is confirmed

before 20 weeks of gestation, treatment with Ig and

termination of pregnancy should be discussed as

options based on local legislation.47 Treatment of

CRS mainly involves long-term interdisciplinary

supportive care for managing clinical manifestations,

close monitoring of neurodevelopmental progress,

and long-term audiological and ophthalmic follow-up.

47

Vaccination is the only practical and effective

way of preventing congenital rubella infection; a single

dose of vaccine can offer long-lasting immunity in

>95% of cases, while two doses given at an appropriate

interval offers close to 100% protection.47 52 While

the rubella vaccine is available as an isolated vaccine,

it is often administered as a combined vaccine with

measles (MR), both measles and mumps (MMR),

or together with varicella (MMRV). Yet the vaccine

is contra-indicated in pregnant women because of

potential transplacental transfer of live rubella virus.

Since 1969 the immunisation against rubella with

live, attenuated virus was first introduced, some

countries have implemented national immunisation

programmes against rubella although no cases of

CRS have been reported due to rubella vaccination

during early pregnancy,54 55 the number of cases of

rubella infection has declined globally.

Under the Hong Kong Childhood

Immunisation Programme, the inclusion of eligible

children who are entitled to free immunisation

against 11 infectious diseases including rubella has

been incorporated into the programme progressively

since 1978.45 Starting from 1982, the two-dose

protocol has covered all eligible children in Hong

Kong. The first dose of MMR vaccine is given at

age 1 year, and the second dose at primary one. The

second dose of MMR vaccine has been replaced

with MMRV vaccine for children born on or after

1 January 2013. The estimated coverage of the first

dose of MMR vaccine in children from aged 2 to 5

years remains high (over 98%).56

Screening for rubella IgG antibodies is

performed in pregnant women during their first

antenatal visit. If the pregnant woman is found to

be non-immune to rubella during the screening,

postpartum vaccination is arranged at the Maternal

Child Health Centre to protect the mother and her

future pregnancies. With universal immunisation

against rubella implemented in Hong Kong, the

seronegativity rate among resident women who delivered their babies in a local hospital was 8.1%,

less than half of the non-residents being 19.9%,

who were mostly Chinese from the mainland China

where there is no such immunisation programme

implemented.57

C – Congenital cytomegalovirus

Cytomegalovirus is a ubiquitous herpesvirus that

can reside in the body after a primary infection

throughout the person’s life.9 Non-primary

infection can result from reactivation of the latent

virus or reinfection by a different strain of CMV.

Approximately 1% to 7% of pregnant women acquire

primary CMV infection; of these, about 30% to 40%

transmit the infection to the fetus.58 59 Congenital

CMV infection represents the most common

congenital viral infection worldwide and is a leading

cause of hearing loss and neurological disabilities in

children.60 61

According to the Centre for Health Protection

of Hong Kong, the seroprevalence rates of CMV

antibodies in local women aged between 20 and

39 years ranged from 50% to 86% in 2015, with the

highest rate in the age-group of 35 to 39 years.62 A

local study of Chinese women in Hong Kong found

a 7.4% prevalence rate of CMV in cervical excretions

during the third trimester, which was low relative

to other Asian countries.63 A 1994 report indicated

that the seroprevalence rate of CMV in Hong Kong

increased steadily from 37% at aged 1 year to 51%

by aged 10 years and increased drastically to almost

100% by aged 21 years, implying that CMV infection

is usually acquired early in life.64

Cytomegalovirus can be transmitted through

direct or indirect contact with infectious body

fluids like saliva, urine, blood, semen, or cervical

or vaginal secretions.60 Maternal CMV infection

is mainly acquired through contact with the

urine or saliva of infected individuals or sexual

contact.60 Cytomegalovirus can be transmitted

transplacentally, resulting in congenital infection,

with the transmission rate reaching approximately

32.3% in mothers with primary infection but only

1.4% in those with non-primary infection.65 Despite

the higher rate of vertical transmission and the

fact that many women of childbearing age are

seropositive for CMV, only one-quarter of congenital

CMV infections are caused by primary maternal

infection, with the rest three-quarters resulting

from non-primary maternal infections.66 The risk of

vertical transmission is approximately 36% when the

primary maternal infection occurs during the first

trimester, whereas in the third trimester67 rise to

77.6%.

Primary CMV infection in immunocompetent

individuals is asymptomatic including 75% to 95%

of pregnant women with infection.9 68 In others, it may present as a mild mononucleosis- or flu-like

syndrome with non-specific symptoms such as

fever and fatigue.68 Nevertheless, congenital CMV

infections can have severe disabling consequences.

Congenital CMV infections from primary

maternal infections are more likely to result in

symptoms and long-term defects in neonates than

those from non-primary maternal infections.58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69

Approximately 10% of newborns congenitally

infected with CMV are symptomatic.65 The most

common manifestations are jaundice at birth,

petechiae, hepatosplenomegaly, small size for age,

and microcephaly.60 Other clinical manifestations

include premature birth, hypotonia, poor feeding,

lethargy, sensorineural hearing loss, chorioretinitis,

hydrocephalus, seizures, thrombocytopenia,

anaemia, and pneumonitis.60 69

The risk of developing central nervous system

(CNS) sequelae is higher if the congenital infection

results from primary maternal infection occurring in

the first trimester than later stage in pregnancy.70 The

development of permanent sequelae is more frequent

in symptomatic newborns, while 10% to 15% of those

who are asymptomatic at birth have developmental

abnormalities including sensorineural hearing loss,

microcephaly, motor defects, mental retardation,

chorioretinitis, and dental defects, usually appearing

before the age of 2 years.9 61 71 For instance, while

nearly 50% of symptomatic neonates develop

sensorineural hearing loss, only 7% of asymptomatic

ones develop it.72 Fetal and neonatal deaths can

also result from congenital CMV infections in

approximately 0.5% of cases.71

A history of maternal primary CMV

infection, together with ultrasonography findings

such as echogenic bowel, bilateral periventricular

cerebral calcifications, hydrocephalus,

microcephaly, fetal growth retardation,

oligohydramnios, polyhydramnios, placentomegaly,

hepatosplenomegaly, hepatic calcifications, ascites,

or hydrops, are suggestive of fetal infection.71 Fetal

CMV infection can be diagnosed by PCR for CMV

DNA and virus isolation from the amniotic fluid, but

PCR does not predict adverse fetal outcomes.68 As

for newborns, isolation of CMV in the infant’s urine

within the first 2 weeks of life is the standard for

diagnosing congenital infection.59

While no prenatal treatment has yet been shown

to reduce in-utero infections or sequelae, antiviral

treatment with ganciclovir and valganciclovir has

been proven to reduce the risk of sensorineural

hearing loss and improve neurodevelopmental

outcomes, especially when treatment is initiated

within the first month after birth in symptomatic

infants and continued for 6 months.73 Meanwhile,

more evidence is needed to justify the risks and

benefits of antiviral treatment in asymptomatic

infants to devise a suitable treatment scheme that helps to minimise the risk of development of severe

sequelae later in life.

Currently, systemic screening for CMV

primary infection is not performed in any one

country.59 Risk reduction strategies should focus

on preventing maternal primary infection during

pregnancy. Thus, proper hygiene practices (eg, hand

washing), reducing maternal exposure to body fluids

that contain the virus (eg, saliva and urine of children

with infection), and access to clean running water

are effective measures to reduce CMV infections.60

H – Congenital herpes simplex virus

Herpes simplex viruses types 1 and 2 are

herpesviruses, which can establish lifelong latency

after the primary infection.74 75 Both types of HSV can

cause genital herpes, which when acquired during

pregnancy may pose a risk of vertical transmission to

the neonate.76 Neonatal HSV infection is estimated

to occur in 1 in 3000 to 20 000 livebirths, but it is rare

in Hong Kong, with only one case of neonatal HSV

type 1 infection reported from 2008 to 2010.75 77

In Hong Kong, HSV infection tends to

be acquired early in life, with a gradual rise in

seropositivity in childhood and a drastic rise in young

adults.64 Infection with HSV occurs through direct

contact of mucosal or abraded skin surfaces with

infectious secretions or lesions, commonly found in

the oral and genital regions.9 Approximately 5% of

neonatal HSV infections occur in utero, 85% during

the peripartum period, and the remaining 10%

postnatally, through direct contact with infectious

lesions or secretions.78 Peripartum infection is

mainly caused by direct contact with infected genital

lesions in the birth canal.79 80 The risk of vertical

transmission is higher in mothers with newly

acquired genital HSV infections than those with

HSV reactivation, with 57% and 2% increases in risk,

respectively.79 80 81 The presence of maternal antibodies

to either HSV subtype seems to offer a certain

degree of protection against neonatal transmission.

Even antibodies against HSV-2 seem to have a

protective effect against neonatal transmission of

both HSV subtypes, women of all HSV serological

statuses can transmit the virus to neonates.79 Genital

infection occurring closer to term incurs a higher

risk of neonatal transmission, with 50% to 80%

risk of neonatal infections resulting from maternal

genital HSV infections close to term.79

The majority of both newly acquired or

recurrent genital HSV infections are asymptomatic

or too mild to be recognised or properly diagnosed,

such that no known history of genital HSV infection

was found in close to 80% of mothers who delivered

an infected infant.9 82

In-utero HSV infection accounts for only

5% of all neonatal HSV infections.9 The triad of

cutaneous, CNS, and ophthalmic findings are typical in this group of infants. Common cutaneous

presentations include vesicles, scarring, aplasia

cutis, and hypopigmentation/hyperpigmentation.

Neurological findings include microcephaly,

intracranial calcifications, and hydranencephaly,

while ophthalmic manifestations typically include

chorioretinitis, microphthalmia, and optic

atrophy.9 76

Peripartum and postnatal HSV infections

share similar clinical manifestations. They can

generally be categorised into three main groups:

disease localised to the skin, eyes, or mouth (SEM

disease); disease localised to the CNS (CNS disease);

and disseminated disease.78 Approximately 45%

of all cases are categorised as SEM disease, and

these cases typically include vesicles on the skin,

keratoconjunctivitis of the eye, and infection of

the oropharynx. Approximately 30% of cases are

categorised as CNS disease, which is mainly caused

by meningoencephalitis and can present with focal

or generalised seizures, fever, lethargy, irritability,

tremors, poor oral intake, temperature instability,

bulging fontanelle, or pyramidal tract signs.9 78

Disseminated disease involving multiple visceral

organs, such as the lungs, liver, heart, and brain,

occurs in the remaining 25% of cases.78 It presents

with irritability, seizures, respiratory failure,

hepatic failure, jaundice, disseminated intravascular

coagulopathy, and shock. Disseminated disease is

associated with a mortality rate of 29%.78

Diagnosis of neonatal HSV infection is

challenging because of its non-specific presentation.

All of the following specimens should be obtained

and sent for PCR assay: surface specimens (mouth,

nasopharynx, conjunctivae, anus), skin vesicles, CSF,

and whole blood.22 Other organ involvement can be

screened by laboratory tests and imaging, such as

alanine transaminase levels as indicator of hepatic

involvement; chest X-ray for lung involvement;

and neuroimaging and electroencephalogram as

indicators of CNS disease.

Antiviral treatment with intravenous acyclovir

is recommended for neonates with HSV infection.

For infants with disseminated or CNS disease, 21

days of antiviral therapy are indicated. For those with

SEM disease, 14 days of treatment is recommended.22

The 14-day treatment is also recommended for

asymptomatic neonates born to mothers who are

infected with HSV close to term.22 The emergence

of antiviral treatment for HSV infection has

contributed to a drastic reduction in the 12-month

mortality rate of infants with disseminated HSV

disease, from 85% to 29% overall, and from 50% to

only 4% in those with CNS disease.78 80 Morbidity

rates and long-term outcomes have also been

improved with the use of antiviral agents, especially

when treatment is initiated as soon as possible with

an early diagnosis.9 78

As the majority of neonatal HSV infections

are peripartum, reducing neonates’ exposure to

active genital lesions during delivery is important

for prevention of transmission. Active genital

HSV lesions or presence of prodromal symptoms

at the time of delivery are indications for delivery

by Caesarean section, which has been found to be

effective in preventing neonatal transmission.76 Oral

acyclovir or valacyclovir as antiviral suppression

therapy, initiated at 36 weeks of gestation, is

associated with reduced genital lesions and

decreased viral detection by viral culture or PCR at

the time of delivery.76 78 More studies are required to

establish its safety and effectiveness as prophylaxis

against neonatal HSV infection.

Counselling on prevention of unprotected

sexual contact during pregnancy, especially late

pregnancy, may reduce the risk of maternal HSV

infection and thus neonatal infection through

vertical transmission.80

Diagnosing TORCH infection

‘TORCH titres’ are often ordered by clinicians who suspect congenital infections; however, various

studies have shown that the diagnostic yield is very

low if they are not used appropriately.83 84 Maternal

IgG antibodies can cross the placenta and IgG antibody titres from one blood sample might not

be adequate for diagnosis. Therefore, appropriate

follow-up testing should be arranged to evaluate

the levels of IgG-specific antibody of concern, and

whenever possible, isolation of the organism should

be attempted.83 Targeted specimens and tests

rather than a TORCH screen should be sent if

the clinical suspicion for a specific congenital

infection is strong after reviewing the maternal

history and infant’s clinical features. The clinical

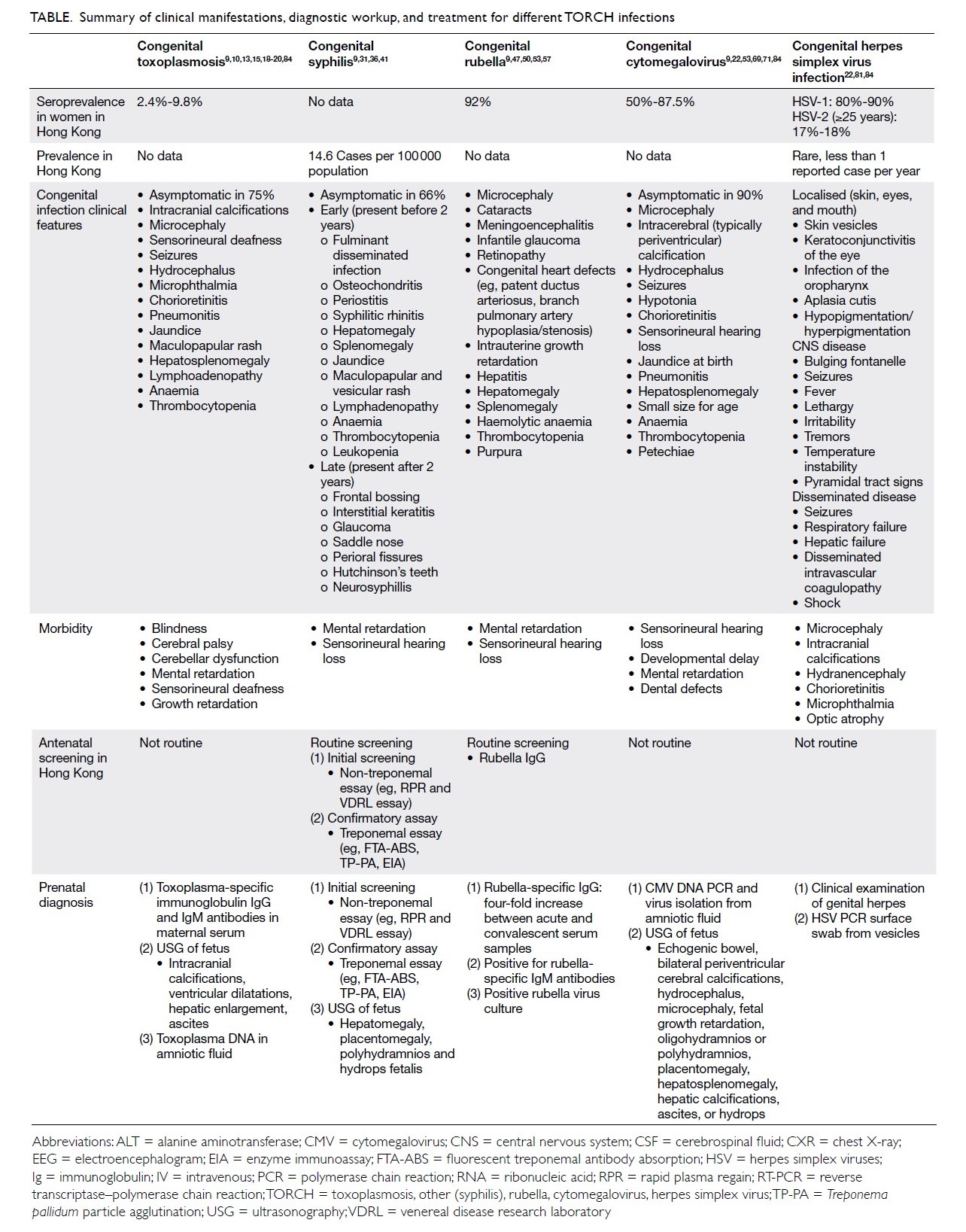

features, antenatal screening, diagnostic testing,

and treatment of congenital toxoplasmosis, syphilis,

rubella, CMV, and HSV are summarised in the

Table.9 10 13 15 18 19 20 22 31 36 4147 50 53 57 69 71 81 84

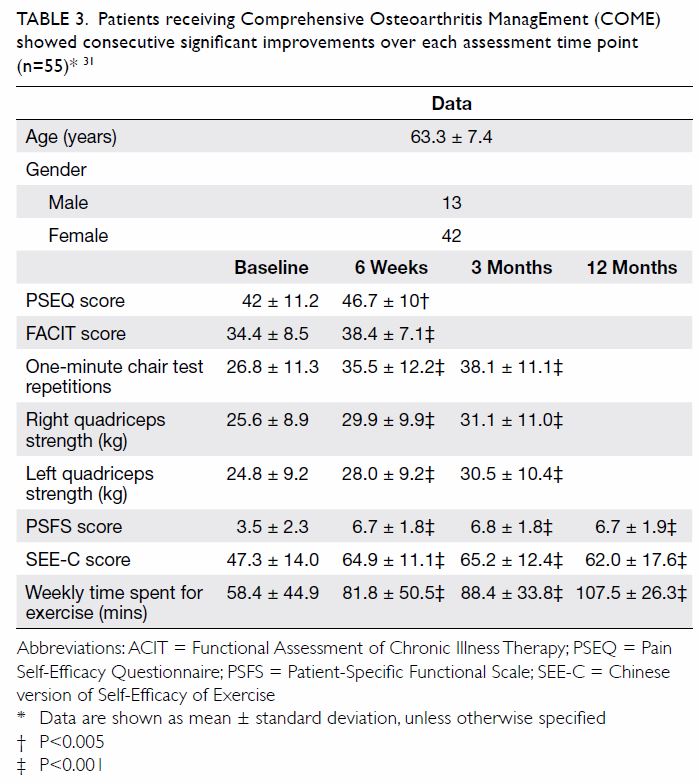

Table. Summary of clinical manifestations, diagnostic workup, and treatment for different TORCH infections

Conclusion

Despite being densely populated, Hong Kong

has relatively low rates of congenital infections.

Nevertheless, it is important to stay vigilant for

infections during pregnancy that may lead to severe

disabilities or even death of the fetus. In Hong Kong,

comprehensive antenatal services that are available to

eligible mothers have been provided free of charge by

the public sector in collaboration with the Maternal

and Child Health Centres (under the Department of

Health) and hospital Obstetrics Departments (under

the Hospital Authority). Pregnant women registered for the shared care system are entitled to receive

regular antenatal check-ups, postnatal services, and

close monitoring of the pregnancy.

Prevention is better than intervention, especially

in the context of congenital infections. Primary

prevention of maternal infection during pregnancy is

the key to preventing congenital infections. Effective

measures for primary prevention are available, and

during the first antenatal visit, screening for rubella,

syphilis, and HIV are performed. Available resources

should focus on promoting public health.

Author contributions

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Concept or design: KL Hon.

Acquisition of data: KKY Leung, A Yeung.

Analysis or interpretation of data: KKY Leung, A Yeung.

Drafting of the article: KL Hon, KKY Leung, A Yeung.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: KL Hon, KKY Leung, AKC Leung, E Man.

Acquisition of data: KKY Leung, A Yeung.

Analysis or interpretation of data: KKY Leung, A Yeung.

Drafting of the article: KL Hon, KKY Leung, A Yeung.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: KL Hon, KKY Leung, AKC Leung, E Man.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, KL Hon was not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. DeVore NE, Jackson VM, Piening SL. TORCH infections. Am J Nurs 1983;83:1660-5. Crossref

2. Neu N, Duchon J, Zachariah P. TORCH infections. Clin Perinatol 2015;42:77-103. Crossref

3. Stegmann BJ, Carey JC. TORCH infections. Toxoplasmosis,

other (syphilis, varicella-zoster, parvovirus B19), rubella,

cytomegalovirus (CMV), and herpes infections. Curr

Womens Health Rep 2002;2:253-8.

4. Schwartz DA. The origins and emergence of Zika virus,

the newest torch infection: what’s old is new again. Arch

Pathol Lab Med 2017;141:18-24. Crossref

5. Nahmias AJ, Walls KW, Stewart, JA, Herrmann KL, Flynt

WJ Jr. The ToRCH complex-perinatal infections associated

with toxoplasma and rubella, cytomegol- and herpes

simplex viruses. Pediatr Res 1971;5:405-6. Crossref

6. Fuerst HT. Flame or bird? Pediatrics 1975;56:107. Crossref

7. Brumback RA. TORCHES. Pediatrics 1976;58:916.

8. World Health Organization. Global validation of

elimination of mother-to child transmission (EMTCT) of

HIV and syphilis. 2019. Available from: https://www.who.

int/reproductivehealth/congenital-syphilis/emtc-gvac/

en/. Accessed 3 Oct 2019.

9. Wilson CB, Nizet V, Maldonado Y, Remington JS, Klein JO.

Remington and Klein’s Infectious Diseases of the Fetus and

Newborn Infant. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders;

2016: 513, 520-5, 675, 677-9, 685-90, 693-4, 729, 732.

10. Montoya JG, Liesenfeld O. Toxoplasmosis. Lancet 2004;363:1965-76. Crossref

11. McAuley JB. Congenital toxoplasmosis. J Pediatric Infect

Dis Soc 2014;3 Suppl 1:S30-5. Crossref

12. Dunn D, Wallon M, Peyron F, Petersen E, Peckham C,

Gilbert R. Mother-to-child transmission of toxoplasmosis:

risk estimates for clinical counselling. Lancet

1999;353:1829-33. Crossref

13. Ko RC, Wong FW, Todd D, Lam KC. Prevalence of

Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in the Chinese population of

Hong Kong. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1980;74:351-4. Crossref

14. Torgerson PR, Mastroiacovo P. The global burden of

congenital toxoplasmosis: a systematic review. Bull World

Health Organ 2013;91:501-8. Crossref

15. Serranti D, Buonsenso D, Valentini P. Congenital

toxoplasmosis treatment. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci

2011;15:193-8.

16. Tamma P. Toxoplasmosis. Pediatr Rev 2007;28:470-1. Crossref

17. Wilson CB, Remington JS, Stagno S, Reynolds DW.

Development of adverse sequelae in children born with

subclinical congenital Toxoplasma infection. Pediatrics

1980;66:767-74.

18. Sever JL, Ellenberg JH, Ley AC, et al. Toxoplasmosis:

maternal and pediatric findings in 23,000 pregnancies.

Pediatrics 1988;82:181-92.

19. Gay-Andrieu F, Marty P, Pialat J, Sournies G, Drier de

Laforte T, Peyron F. Fetal toxoplasmosis and negative

amniocentesis: necessity of an ultrasound follow-up.

Prenat Diagn 2003;23:558-60. Crossref

20. Cortina-Borja M, Tan HK, Wallon M, et al. Prenatal

treatment for serious neurological sequelae of congenital

toxoplasmosis: an observational prospective cohort study.

PLoS Med 2010;7(10). pii: e1000351. Crossref

21. Pomares C, Montoya JG. Laboratory diagnosis of congenital

toxoplasmosis. J Clin Microbiol 2016;54:2448-54. Crossref

22. Kimberlin DW, Brady MT, Jackson MA, editors. Red Book

2018: Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases.

31st ed. Itasca; American Academy of Pediatrics; 2018:

310-7, 437-48, 459-76, 773-88, 809-19, 8698.

23. Chik TS, Tsang OT. Toxoplasmosis. HIV manual. 4th ed.

2019. Available from: https://hivmanual.hk/d27/. Accessed

7 Oct 2019.

24. Cook AJ, Gilbert RE, Buffolano W, et al. Sources of

toxoplasma infection in pregnant women: European

multicentre case-control study. European Research

Network on Congenital Toxoplasmosis. BMJ 2000;321:142-

7. Crossref

25. Halonen SK, Weiss LM. Toxoplasmosis. Handb Clin

Neurol 2013;114:125-45. Crossref

26. Jones JL, Krueger A, Schulkin J, Schantz PM. Toxoplasmosis

prevention and testing in pregnancy, survey of obstetriciangyn-aecologists.

Zoonoses Public Health 2010;57:27-33. Crossref

27. Sagel U, Krämer A. Screening of maternal toxoplasmosis in

pregnancy: laboratory diagnostics from the perspective of

public health requirements. J Bacteriol Parasitol 2013;S5.

28. Cornu C, Bissery A, Malbos C, et al. Factors affecting

the adherence to an antenatal screening programme: an

experience with toxoplasmosis screening in France. Euro

Surveill 2009;14:21-5.

29. Paquet C, Yudin MH; Society of Obstetricians and

Gynaecologists of Canada. Toxoplasmosis in pregnancy:

prevention, screening, and treatment [in English, French].

J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2013;35:78-81. Crossref

30. World Health Organization. The global elimination of congenital syphilis: rationale and strategy for

action. 2017. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/

handle/10665/43782. Accessed 8 Oct 2019.

31. Special Preventive Programme, Centre for Health

Protection, Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Hong Kong STD/AIDS update—a quarterly

surveillance report. Vol 23 No 4, 2017. Available from:

https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/std17q4.pdf. Accessed 8

Oct 2019.

32. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US

Government. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance.

Primary and secondary syphilis—rates of reported cases

by state, United States and outlying areas, 2017. Available

from: https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/figures/37.htm.

Accessed 3 Oct 2019.

33. Fiumara NJ. Syphilis in newborn children. Clin Obstet

Gynecol 1975;18:183-9. Crossref

34. Jenson HB. Congenital syphilis. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis

1999;10:183-94. Crossref

35. Herremans T, Kortbeek L, Notermans DW. A review of

diagnostic tests for congenital syphilis in newborns. Eur J

Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2010;29:495-501. Crossref

36. De Santis M, De Luca C, Mappa I, et al. Syphilis infection

during pregnancy: fetal risks and clinical management.

Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2012;2012:430585. Crossref

37. Leung AK, Leong KF, Lam JM. A case of congenital syphilis

presenting with unusual skin eruptions. Case Rep Pediatr

2018;2018:1761454. Crossref

38. Lago EG, Vaccari A, Fiori RM. Clinical features and follow-up

of congenital syphilis. Sex Transm Dis 2013;40:85-94. Crossref

39. Woods CR. Syphilis in children: congenital and acquired.

Semin Pediatr Infect Dis 2005;16:245-57. Crossref

40. Mannelli L, Perez FA, Parisi MT, Giacani L. A case of

congenital syphilis. Emerg Radiol 2013;20:337-9. Crossref

41. Public Health Agency of Canada. Government of Canada.

Section 5-10: Canadian guidelines on sexually transmitted

infections—management and treatment of specific

infections—syphilis. 2019. Available from: https://www.

canada.ca/en/public-health/services/infectious-diseases/

sexual-health-sexually-transmitted-infections/canadianguidelines/

sexually-transmitted-infections/canadianguidelines-

sexually-transmitted-infections-27.html.

Accessed 3 Oct 2019.

42. Alexander JM, Sheffield JS, Sanchez PJ, Mayfield J, Wendel

GD Jr. Efficacy of treatment for syphilis in pregnancy.

Obstet Gynecol 1999;93:5-8. Crossref

43. Sheffield JS, Sánchez PJ, Morris G, et al. Congenital syphilis

after maternal treatment for syphilis during pregnancy.

Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;186:569-73. Crossref

44. Duthie SJ, King PA, Yung GL, Ma HK. Routine serological

screening for syphilis during pregnancy—disposable

anachronism or fundamental necessity? Aust N Z J Obstet

Gynaecol 1990;30:29-31. Crossref

45. Ho FW. Update on rubella in Hong Kong. Commun Dis

Watch 2017;14:66-8.

46. Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong

Kong SAR Government. Number of notifiable infectious

diseases by month. 2019. Available from: https://www.chp.

gov.hk/en/static/24012.html. Accessed 3 Oct 2019.

47. Leung AK, Hon KL, Leong KF. Rubella (German measles)

revisited. Hong Kong Med J 2019;25:134-41. Crossref

48. Miller E, Cradock-Watson JE, Pollock TM. Consequences

of confirmed maternal rubella at successive stages of pregnancy. Lancet 1982;2:781-4. Crossref

49. Dontigny L, Arsenault MY, Martel MJ; Clinical Practice

Obstetrics Committee. Rubella in pregnancy. J Obstet

Gynaecol Can 2008;30:152-8. Crossref

50. Reef SE, Plotkin S, Cordero JF, et al. Preparing for

elimination of congenital rubella syndrome (CRS):

summary of a workshop on CRS elimination in the United

States. Clin Infect Dis 2000;31:85-95. Crossref

51. Watson JC, Hadler SC, Dykewicz CA, Reef S, Phillips L.

Measles, mumps, and rubella—vaccine use and strategies

for elimination of measles, rubella, and congenital rubella

syndrome and control of mumps: recommendations of the

Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

MMWR Recomm Rep 1998;47:1-57.

52. Rubella vaccines: WHO position paper [editorial] [in

English, French]. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2011;86:301-16.

53. World Health Organization. Manual for the laboratory

diagnosis of measles and rubella virus infection Second

edition. 2017. Available from: https://www.who.int/ihr/

elibrary/manual_diagn_lab_mea_rub_en.pdf. Accessed 8

Oct 2019.

54. Bart SW, Stetler HC, Preblud SR, et al. Fetal risk associated

with rubella vaccine: an update. Rev Infect Dis 1985;7

Suppl 1:S95-102. Crossref

55. Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Rubella vaccination

during pregnancy—United States, 1971-1988. MMWR

Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1989;38:289-93.

56. Food and Health Bureau, Hong Kong SAR Government.

Hong Kong reference framework for preventive care

for children in primary care settings. 2012. Available

from: https://www.fhb.gov.hk/pho/english/health_

professionals/professionals_preventive_children_pdf.

html. Accessed 10 Oct 2019.

57. Lao TT, Suen SS, Leung TY, Sahota DS, Lau TK.

Universal rubella vaccination programme and maternal

rubella immune status: a tale of two systems. Vaccine

2010;28:2227-30. Crossref

58. Boppana SB, Rivera LB, Fowler KB, Mach M, Britt WJ.

Intrauterine transmission of cytomegalovirus to infants

of women with preconceptional immunity. N Engl J Med

2001;344:1366-71. Crossref

59. Lazzarotto T, Guerra B, Gabrielli L, Lanari M, Landini

MP. Update on the prevention, diagnosis and management

of cytomegalovirus infection during pregnancy. Clin

Microbiol Infect 2011;17:1285-93. Crossref

60. Cannon MJ. Congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV)

epidemiology and awareness. J Clin Virol 2009;46 Suppl

4:S6-10. Crossref

61. Boppana SB, Ross SA, Fowler KB. Congenital

cytomegalovirus infection: clinical outcome. Clin Infect

Dis 2013;57 Suppl 4:S178-81. Crossref

62. Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health,

Hong Kong SAR Government. Seroprevalence rates of

cytomegalovirus antibodies. 2018. Available from: https://

www.chp.gov.hk/en/statistics/data/10/641/701/6445.html.

Accessed 5 Oct 2019.

63. Leung AK, Loong EP, Chan RC, Murray HG, Chang

AM. Prevalence of cytomegalovirus cervical excretion in

pregnant women in Hong Kong. Asia Oceania J Obstet

Gynaecol 1989;15:77-8. Crossref

64. Kangro HO, Osman HK, Lau YL, Heath RB, Yeung CY, Ng

MH. Seroprevalence of antibodies to human herpesviruses

in England and Hong Kong. J Med Virol 1994;43:91-6. Crossref

65. Kenneson A, Cannon MJ. Review and meta-analysis of

the epidemiology of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV)

infection. Rev Med Virol 2007;17:253-76. Crossref

66. Wang C, Zhang X, Bialek S, Cannon MJ. Attribution

of congenital cytomegalovirus infection to primary

versus non-primary maternal infection. Clin Infect Dis

2011;52:e11-3. Crossref

67. Bodéus M, Hubinont C, Goubau P. Increased risk of

cytomegalovirus transmission in utero during late

gestation. Obstet Gynecol 1999;93(5 Pt 1):658-60. Crossref

68. Nigro G. Maternal-fetal cytomegalovirus infection:

from diagnosis to therapy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med

2009;22:169-74. Crossref

69. Leung AK, Sauve RS, Davies HD. Congenital

cytomegalovirus infection. J Natl Med Assoc 2003;95:213-

8.

70. Pass RF, Fowler KB, Boppana SB, Britt WJ, Stagno S.

Congenital cytomegalovirus infection following first

trimester maternal infection: symptoms at birth and

outcome. J Clin Virol 2006;35:216-20. Crossref

71. Dollard SC, Grosse SD, Ross DS. New estimates of the

prevalence of neurological and sensory sequelae and

mortality associated with congenital cytomegalovirus

infection. Rev Med Virol 2007;17:355-63. Crossref

72. Dahle AJ, Fowler KB, Wright JD, Boppana SB, Britt WJ,

Pass RF. Longitudinal investigation of hearing disorders

in children with congenital cytomegalovirus. J Am Acad

Audiol 2000;11:283-90.

73. Demmler-Harrison GJ. Congenital cytomegalovirus

infection: management and outcome. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/congenital-cytomegalovirus-infection-management-and-outcome.

Accessed 10 Oct 2019.

74. Leung AK, Barankin B. Herpes labialis: an update. Recent

Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov 2017;11:107-13. Crossref

75. Hon KL, Leung TF, Cheung HM, Chan PK. Neonatal

herpes: what lessons to learn. Hong Kong Med J 2012;18:60-

2.

76. James SH, Sheffield JS, Kimberlin DW. Mother-to-child

transmission of herpes simplex virus. J Pediatric Infect Dis

Soc 2014;3 Suppl 1:S19-23. Crossref

77. Sauerbrei A. Genital herpes. In: Diagnostics to

Pathogenomics of Sexually Transmitted Infections. West

Sussex; John Wiley & Sons Ltd: 2018: 83-99. Crossref

78. Kimberlin DW. Herpes simplex virus infections of the

newborn. Semin Perinatol 2007;31:19-25. Crossref

79. Brown ZA, Selke S, Zeh J, et al. The acquisition of genital

herpes during pregnancy. N Engl J Med 1997;337:509-15. Crossref

80. Corey L, Wald A. Maternal and neonatal herpes simplex

virus infections. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1376-85. Crossref

81. Lee NL, Tse IC. V. Major opportunistic infections. Herpes

simplex and zoster. 2019. Available from: https://www.aids.

gov.hk/pdf/g190htm/25.htm. Accessed 1 Jan 2020.

82. Whitley RJ, Corey L, Arvin A, et al. Changing patterns of

herpes simplex virus infection in neonates. J Infect Dis

1988;158:109-16. Crossref

83. Leland D, French ML, Kleiman MB, Schreiner RL. The use

of TORCH titers. Pediatrics 1983;72:41-3.

84. Lim WL, Wong DA. TORCH screening: time for abolition?

J Hong Kong Med Assoc 1994;46:306.