Hong Kong Med J 2018 Apr;24(2):175–81 | Epub 6 Apr 2018

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj177086

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REVIEW ARTICLE

Management of complications of ketamine abuse: 10

years’ experience in Hong Kong

YL Hong, MSc1; CH Yee, FHKAM (Surgery)2,

YH Tam, FHKAM (Surgery)1; Joseph HM Wong, FHKAM (Surgery)2;

PT Lai, BN2; CF Ng, FHKAM (Surgery)2

1 Division of Paediatric Surgery and

Paediatric Urology, Department of Surgery, The Chinese University of Hong

Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

2 SH Ho Urology Centre, Department of

Surgery, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof CF Ng (ngcf@surgery.cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Ketamine is an N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor

antagonist, a dissociative anaesthetic agent and a treatment option for

major depression, treatment-resistant depression, and bipolar disorder.

Its strong psychostimulant properties and easy absorption make it a

favourable candidate for substance abuse. Ketamine entered Hong Kong as a

club drug in 2000 and the first local report of ketamine-associated

urinary cystitis was published in 2007. Ketamine-associated lower–urinary

tract symptoms include frequency, urgency, nocturia, dysuria, urge

incontinence, and occasionally painful haematuria. The exact prevalence of

ketamine-associated urinary cystitis is difficult to assess because the

abuse itself and many of the associated symptoms often go unnoticed until

a very late stage. Additionally, upper–urinary tract pathology, such as

hydronephrosis, and other complications involving neuropsychiatric,

hepatobiliary, and gastrointestinal systems have also been reported.

Gradual improvement can be expected after abstinence from ketamine use.

Sustained abstinence is the key to recovery, as relapse usually leads to

recurrence of symptoms. Both medical and surgical management can be used.

The Youth Urological Treatment Centre at the Prince of Wales Hospital,

Hong Kong, has developed a four-tier treatment protocol with initial

non-invasive investigation and management for these patients.

Multidisciplinary care is essential given the complex and diverse

psychological factors and sociological background that underlie ketamine

abuse and abstinence status.

Introduction

Ketamine is an N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor

antagonist, a dissociative anaesthetic agent that was first

synthesised in the United States in 1962. It has been widely used in both

human and veterinary medicine since 1971. It has also been used as a

treatment for major depression, treatment-resistant depression, and

bipolar disorder.1 However, its

strong psychostimulant properties and easy absorption make it a favourable

candidate for substance abuse. Ketamine abuse has become increasingly

common over the past two decades. It entered Hong Kong as a club drug in

2000 and was initially used as a ‘top-up’ drug to ecstasy

(3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine) by those aiming to elevate and

redirect the ‘high’.2 It was viewed

as a poor man’s version of cocaine, as it is available in powder form and

can be consumed by snorting. By 2002, ketamine had become the drug of

choice instead of a ‘top-up’ drug. Users self-administered ketamine to

have a ‘time-out’ or ‘sit-down-to-float’ experience.2 3 Within a

short period, the number of reported ketamine abusers in Hong Kong

increased from 1605 in 2000 to its peak of 5280 in 2009. Ketamine remained

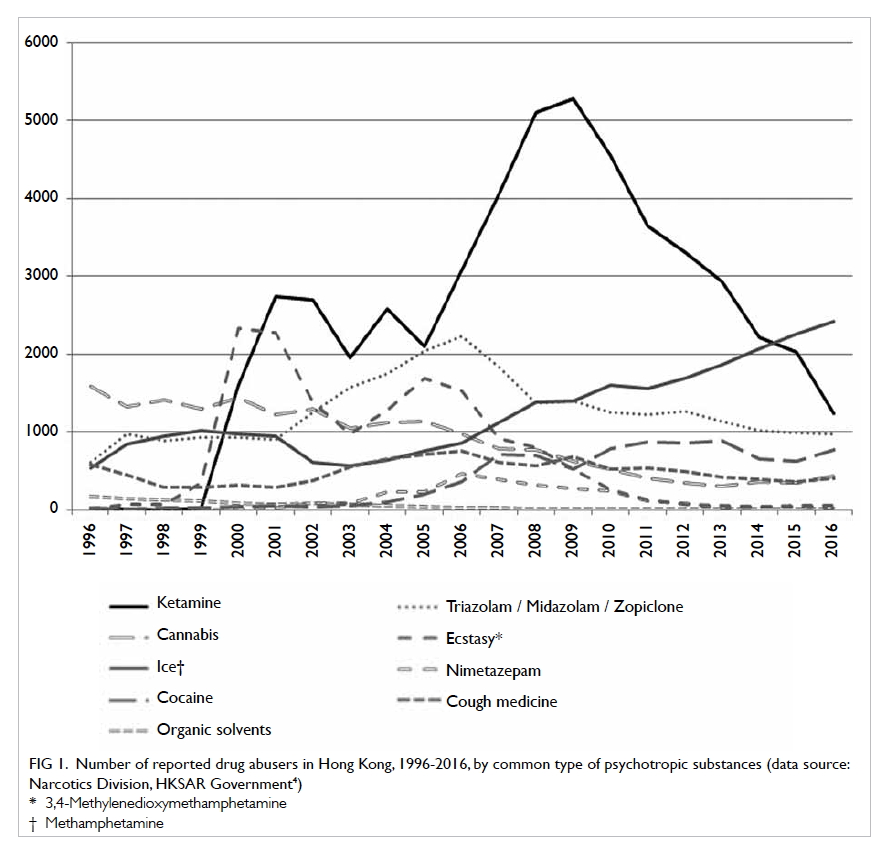

the most popular psychotropic substance abused from 2005 to 2014 (Fig

1).4

Figure 1. Number of reported drug abusers in Hong Kong, 1996-2016, by common type of psychotropic substances (data source: Narcotics Division, HKSAR Government4)

The abuse of ketamine and its popularity

nonetheless created a new medical entity. The first report of

ketamine-associated urinary cystitis in Hong Kong was published in 2007.5 In the same year, Shahani et al

reported a similar condition overseas.6

In the past decade, owing to the joint efforts of urologists, general

surgeons, physicians, psychiatrists, pathologists, and basic scientists,

we have gained a better understanding of other ketamine-associated

conditions. This understanding spans from pathology to clinical

management, from urological complications to upper-gastrointestinal (GI)

complications, and from a mouse model to humans. We have also explored

holistic ways to manage this condition in the long term, such as helping

young adults to have a fresh start while living with potentially

irreversible complications. This article reviews the evolution of local

clinical awareness and management of these complications, with a

particular focus on the work and contributions of local researchers.

Urological complications

Chu et al5

reported the first local case series of ketamine-associated bladder

dysfunction in 2007. Ketamine-associated lower–urinary tract symptoms

(LUTS) include frequency, urgency, nocturia, dysuria, urge incontinence,

and occasionally painful haematuria. The exact prevalence of

ketamine-associated urinary cystitis is difficult to assess because

ketamine abuse and many of the associated symptoms often go unnoticed

until a very late stage. A survey among 12 000 local secondary school

students revealed that 18.5% of non-psychotropic substance users had LUTS,

whereas 47.8% and 60.7% of psychotropic substance users and ketamine users

had LUTS, respectively.7

Unpublished data from the same study showed that compared with

non-psychotropic substance users, sole ketamine users were five times as

likely to have LUTS, whereas concomitant users of ketamine and

methamphetamine were eight times as likely to have LUTS.

In 2015, Yee et al8

reported the largest available cohort of both active and past ketamine

users who had ketamine-associated uropathy. Among 463 patients, ketamine

users had a significantly higher pelvic pain and urgency/frequency (PUF)

score than ex-ketamine users. The PUF score is initially used to assess

interstitial cystitis, and a higher PUF score correlates with worse

symptoms. Among active ketamine users, a higher PUF score was found to

correlate with a poorer quality of life and a smaller functional bladder

capacity.8 Achieving abstinence

from ketamine use and consuming smaller amounts of ketamine were factors

that predicted improvement in PUF score.

As well as bladder involvement, upper–urinary tract

pathology presenting as hydronephrosis and flank pain has also been

reported (Fig 2). A study by Yee et al9 of 572 patients with ketamine-related LUTS found that

up to 16.8% (n=96) of patients had hydronephrosis according to

ultrasonography. Hydronephrosis was frequently accompanied by ureteral

lesions, ureteral wall thickening, or vesicoureteral (vesicoureteric)

reflux. Similarly, Chu et al10

reported that 51% (30/59) of their patients had hydronephrosis according

to ultrasonography.

Figure 2. Intravenous urogram of a 28-year-old woman presenting to the Prince of Wales Hospital, showing bilateral hydronephrosis and small bladder

Pathophysiology

Although the exact mechanism of ketamine-associated

cystitis remains to be explored, there is evidence that ketamine

metabolites in the urine induce chemical irritation of the urothelium,

thereby causing an inflammatory response.11

Severe irritation may lead to denudation of the urothelium and consequent

transmural inflammation, loss of muscle thickness, fibrosis of the

detrusor muscle, and ultimately poor urinary bladder compliance.

Vesicoureteral reflux or urinary stasis in the ureter may occur, causing

chronic ureteral inflammation and ureteral stricture. There is also

evidence that both systemic and local inflammatory markers are elevated in

ketamine users.10 12 In addition, the NMDA antagonist properties of

ketamine may exert their effect via a central pathway.13

Neuropsychiatric complications

As ketamine is a psychostimulant, it is not

surprising that it is associated with long-term neurocognitive problems.

Chan et al14 found that when

ketamine users were compared with healthy controls, they had impaired

verbal fluency, cognitive processing speed, and verbal learning. Heavy

ketamine use correlated with deficits in verbal memory and visual

recognition memory. Liang et al15

also identified predominant verbal and visual memory impairment in

ketamine poly-drug users. Unfortunately, these deficits persisted in

ex-users. A much higher incidence of psychiatric co-morbidities, including

psychosis, depression, and anxiety, was observed among ketamine users.16

Pathophysiology

Structural brain damage associated with ketamine

abuse was supported by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) by Wang et al.17 They were the first group to report patches of

degeneration in the superficial white matter as early as 1 year after

ketamine addiction onset. Cortical atrophy was also found in the frontal,

parietal, or occipital cortices of addicts.17

Another MRI study also provided evidence of brain damage in chronic

ketamine users. Reduced grey- and white-matter volumes were noted in the

bilateral orbitofrontal cortex, right medial prefrontal cortex, and

bilateral hippocampi. There was also significantly decreased connectivity

inside the brain in chronic ketamine abusers.18

A series of studies on the neurotoxicity of

ketamine suggested that ketamine could cause apoptosis of neuronal cells

in both in-vitro and in-vivo models. Ketamine also

potentially causes phosphorylation of tau protein, a marker of Alzheimer’s

degeneration in the brain.19 20 21 22

Hepatobiliary complications

In 2009, Wong et al23

reported ketamine-associated hepatobiliary complications for the first

time. Three ketamine abusers presented with recurrent epigastric pain and

dilated bile ducts mimicking choledochal cysts. Subsequently, more similar

cases were identified. Fusiform dilatation of the common bile duct was

also observed.24 25 26 Liver

biopsy confirmed development of active liver and/or bile duct injury. A

study of 297 chronic ketamine abusers with urinary tract dysfunction

showed that the prevalence of liver injury was 9.8%.27 These studies and reports show the possibility and

severity of damage by ketamine to the hepatobiliary and pancreatic system.

Pathophysiology

The exact mechanism of ketamine-associated bile

injury is still unknown. The associated rise in C-reactive protein

suggests a possible inflammatory process in the liver parenchyma,

including or excluding the bile duct.27

Others have postulated that either central or direct action of ketamine on

the biliary smooth muscle in turn leads to the cholestasis and biliary

dilatation observed in ketamine abusers.28

Gastrointestinal complications

In addition to urological complaints, GI problems

are also frequently the symptoms for which ketamine abusers seek medical

help. A review of 233 ketamine-related visits to accident and emergency

departments found that 49 (21.0%) patients had abdominal pain, 23 (9.9%)

had nausea or vomiting, and 41 (17.6%) had abdominal tenderness.29 Gastrointestinal complaints often co-exist with and

precede the presentation of urological symptoms. Liu et al30 found that about a quarter (168; 27.5%) of 611

ketamine users who sought treatment for ketamine uropathy reported the

presence of upper-GI symptoms, whereas only 42 (5.2%) of 804 non-ketamine

users attending a general urology clinic reported similar symptoms

(P<0.001). The majority of the symptoms reported were epigastric pain

and recurrent vomiting. Nearly three-quarters of patients required

hospitalisation for acute or chronic upper-GI symptoms. With the exception

of acid reflux and perforated peptic ulcer, the prevalence of all the

above-mentioned symptoms and hospitalisation rates were statistically

significantly higher in ketamine users than in non-ketamine users. All 168

patients using ketamine had undergone oesophagogastroduodenoscopy during

which biopsies were taken. Pathological findings ranged from gastritis to

gastroduodenal erosions, peptic ulceration, and intestinal metaplasia.30

Liu et al30

also found that more than 80% of patients developed upper-GI symptoms

before urological symptoms. Patients developed upper-GI symptoms after a

mean (standard deviation) of 5.1 (3.1) years of ketamine use and developed

uropathy symptoms after another 4.4 (3.0) years of ketamine use.30 Epigastric symptoms are not common in young people,

but common in ketamine abusers. This difference may provide an opportunity

to identify hidden ketamine abuse when assessing young patients with

epigastric symptoms. The identification of ketamine use is important, as

cessation of use can greatly improve GI symptoms.31

Further referral for help and counselling may improve psychological and

physical health and promote long-term ketamine abstinence.

Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiological mechanism by which

ketamine produces upper-GI toxicity remains unknown but there are several

postulations. First, ketamine, as an NMDA antagonist, might act on local

smooth muscle or the central nervous system, thereby affecting gastric

motility and leading to cramping pain. Second, microvascular damage by

ketamine and its metabolites, which was believed to be a possible cause of

ketamine uropathy, might also cause similar microvascular damage in the

stomach and duodenum, leading to ischaemic pain and inflammation.

Likewise, circulating ketamine might also trigger some unknown autoimmune

responses, and thus induce interstitial inflammation in the urinary and GI

tracts. Finally, as many ketamine abusers like to swallow the nasal drips

occurring from ketamine inhalation, the swallowed ketamine might also

induce direct cytotoxic injury to the vulnerable GI tract.30

Management

As in the management of other substance abuse,

abstinence is the key to success in overall management of ketamine use.

Whereas other treatment modalities may relieve symptoms and hasten the

recovery process, many ketamine abusers have complicated underlying

psychosocial problems and psychiatric co-morbidities. Long-term and

consistent support and encouragement from doctors, nurses, social workers,

family, and friends are vital for success.

Abstinence from ketamine use

Recurrence of symptoms after resuming ketamine use

highlights the importance of ketamine abstinence. Studies have shown that

abstinence leads to symptomatic improvement. Compared with active ketamine

abusers, those who had abstained for 1 year had significantly lower PUF

scores and a larger voided volume. There was a trend towards higher voided

volumes and lower PUF scores as duration of ketamine cessation increased,

although neither variable was statistically significant.32 Another follow-up study of 101 participants who had

abstained from ketamine and 218 active ketamine users showed that the

abstinence group had a statistically significantly lower PUF score, and a

higher functional bladder capacity.8

Moreover, abstinence was the only protective factor associated with fewer

symptoms, larger voided volume, and bladder capacity.33

Nonetheless, abstinence does not lead to immediate

and full recovery of symptoms. Gradual improvement can be expected but

sustained abstinence is the key to recovery. Patience and continuous

support are of paramount importance. A study showed that on admission to a

drug rehabilitation centre, 90% of 40 female ex-ketamine users still had

active urinary symptoms, with increased 24-hour urinary frequency, lower

maximum voided volume, smaller median functional bladder capacity, and

higher mean Urogenital Distress Inventory Short Form (UDI-6) and

Incontinence Impact Questionnaire Short Form (IIQ-7) scores, when compared

with age-matched controls who attended a general gynaecology clinic. After

having stopped using ketamine for 3 months or more, mean 24-hour urinary

frequency and mean UDI-6 and IIQ-7 scores decreased, and maximum voided

volume increased. These scores further improved after another 3 months,

although this group continued to perform more poorly in all aspects

compared with controls.34

Medical and surgical management

As ketamine-associated uropathy is an evolving

‘disease entity’, the exact pathophysiology remains to be elucidated. Some

of the clinical features share similarities with interstitial cystitis.

Protocols are being developed to cater to the needs of patients in Hong

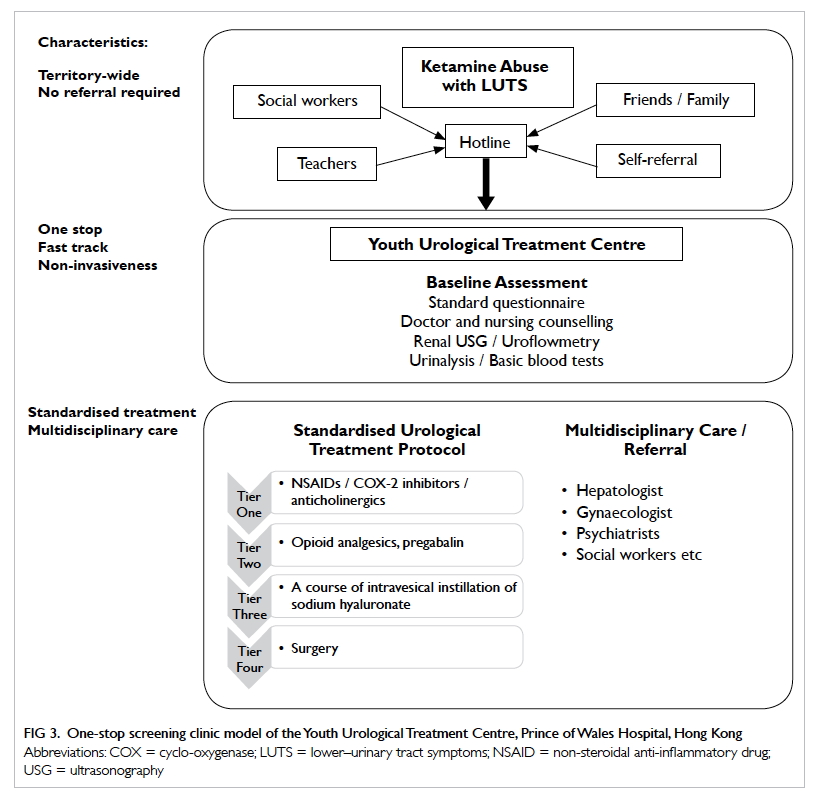

Kong. A one-stop service model has been adopted by the Youth Urological

Treatment Centre at the Prince of Wales Hospital since 2011 (Fig

3). The standard treatment protocol involves four tiers of

treatment, starting with an initial non-invasive investigative approach,

including questionnaire assessment of symptoms and calculation of (1)

functional bladder capacity by measuring voided volume using uroflowmetry

and (2) residual urine using ultrasound bladder scanning. This

non-invasive investigative approach helps gain patients’ trust and improve

adherence to later follow-up.

Figure 3. One-stop screening clinic model of the Youth Urological Treatment Centre, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong

First-tier treatment includes oral non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (eg, diclofenac) and anticholinergics

(eg, solifenacin) or COX-II inhibitors (eg, etoricoxib) if patients cannot

tolerate NSAIDS. Simple analgesics such as paracetamol and phenazopyridine

are used for pain control. The Youth Urological Treatment Centre has

reported the largest series of patients with ketamine-associated uropathy

and their corresponding outcomes. Of 290 patients with ketamine cystitis

who received first-line treatment, 202 (69.7%) reported symptom

improvement and a reduction in PUF scores. Functional bladder capacity was

also shown to have improved.8

The opioid group of analgesics and pregabalin are

used in the next tier of pain-control treatment when first-tier treatment

is insufficient for symptom relief. Sixty-two patients received

second-line treatment and 42 (67.7%) responded to treatment.8

Third-tier treatment consists of a course of

intravesical instillation of sodium hyaluronate (6-weekly instillations

followed by 2-monthly instillations) attempting to repair the

glycosaminoglycan layer. The drug is given to patients whose symptoms

remain uncontrolled after second-tier treatment. Seventeen patients in the

cohort received the third-tier treatment and eight completed the course.

Significant improvement in voided volume was noted and five were able to

reduce their oral medication usage after treatment. No significant adverse

effects were reported.8

Unfortunately, for a proportion of patients with

extremely refractory symptoms, surgery becomes the fourth-tier treatment

of choice. In the Youth Urological Treatment Centre series, one patient in

the cohort required hydrodistension and another underwent robotic-assisted

laparoscopic augmentation cystoplasty. The patient with hydrodistension

experienced a recurrence of symptoms post-treatment.8 Ng et al35

reported on four patients who underwent augmentation cystoplasty. Although

they showed initial improvement, all patients relapsed and resumed

ketamine use postoperatively. Three of the patients showed a further

deterioration in renal function, secondary to new-onset ureteral

strictures and/or sepsis. Therefore, patient selection, education, close

follow-up, and support are vital to the success of augmentation

cystoplasty.35

Multidisciplinary care

Given the complex and diverse psychological factors

and sociological background contributing to an individual’s decision to

abuse ketamine or achieve abstinence, joint multidisciplinary efforts are

required to help affected young adults. Doctors, social workers, teachers,

psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, and patients’ families all need to

support them on their long road to recovery, to help them rehabilitate

physically and achieve sustained abstinence from ketamine.33 36 37

Conclusion

Since the initial discovery of ketamine-associated

uropathy, the impact of this disease entity has become more prominent in

Asian countries. Thanks to the joint efforts of urologists,

gynaecologists, surgeons, psychiatrists, pathologists, and social workers,

as well as the support of local government, the extent of medical

complications has been revealed to also involve the brain, liver, and GI

system. Many ketamine abusers are ‘hidden’ and can use ketamine stealthily

at home for years without their family noticing. Clinicians must take the

opportunity to identify hidden abusers when they consult for non-specific

symptoms such as epigastric pain and LUTS. Doing so will not only enable

early diagnosis of ketamine-associated uropathy, but it will also help

provide appropriate medical treatment in a timely manner. In addition to

medical therapy, referral for appropriate psychosocial support is

essential to sustain abstinence and manage underlying psychosocial

problems.

Acknowledgement

The Youth Urological Treatment Centre was developed

by joint efforts of The Chinese University of Hong Kong and the Hong Kong

Hospital Authority, with generous support from the Beat Drugs Fund of the

Narcotics Division, Security Bureau, Government of the Hong Kong Special

Administrative Region.

Declaration

The authors have no conflicts of interest to

disclose.

References

1. Hasselmann HW. Ketamine as

antidepressant? Current state and future perspectives. Curr Neuropharmacol

2014;12:57-70. Crossref

2. Joe Laidler KA. The rise of club drugs

in a heroin society: the case of Hong Kong. Subst Use Misuse

2005;40:1257-78. Crossref

3. Joe-Laidler K, Hunt G. Sit down to

float: the cultural meaning of ketamine use in Hong Kong. Addict Res

Theory 2008;16:259-71. Crossref

4. Narcotics Division, Security Bureau,

HKSAR Government. Statistical tables customization. Available from:

http://cs-crda.nd.gov.hk/en/enquiry.php. Accessed 22 Sep 2017.

5. Chu PS, Kwok SC, Lam KM, et al. ‘Street

ketamine’–associated bladder dysfunction: a report of ten cases. Hong Kong

Med J 2007;13:311-3.

6. Shahani R, Streutker C, Dickson B, et

al. Ketamine-associated ulcerative cystitis: a new clinical entity.

Urology 2007;69:810-2. Crossref

7. Tam YH, Ng CF, Wong YS, et al.

Population-based survey of the prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms

in adolescents with and without psychotropic substance abuse. Hong Kong

Med J 2016;22:454-63. Crossref

8. Yee CH, Lai PT, Lee WM, et al. Clinical

outcome of a prospective case series of patients with ketamine cystitis

who underwent standardized treatment protocol. Urology 2015;86:236-43. Crossref

9. Yee CH, Teoh YC, Lai PT, et al. The risk

of upper urinary tract involvement in patients with ketamine-associated

uropathy. Int Neurourol J 2017;21:128-32. Crossref

10. Chu PS, Ma WK, Wong SC, et al. The

destruction of the lower urinary tract by ketamine abuse: a new syndrome?

BJU Int 2008;102:1616-22. Crossref

11. Chu PS, Ng CF, Ma WK. Ketamine

uropathy: Hong Kong experience. In: Yew DT, editor. Ketamine: Use and

Abuse. CRC Press; 2015: 207-26.

12. Division of Urology, Department of

Surgery, Princess Margaret Hospital and Tuen Mun Hospital. Research on

Urological Sequelae of Ketamine Abuse. Available from:

http://www.nd.gov.hk/pdf/20110307_beat_drug_fund_report.pdf. Accessed 22

Sep 2017.

13. Jankovic SM, Jankovic SV, Stojadinovic

D, et al. Effect of exogenous glutamate and N-methyl-D-aspartic acid on

spontaneous activity of isolated human ureter. Int J Urol 2007;14:833-7. Crossref

14. Chan KW, Lee TM, Siu AM, et al.

Effects of chronic ketamine use on frontal and medial temporal cognition.

Addict Behav 2013;38:2128-32. Crossref

15. Liang HJ, Lau CG, Tang A, et al.

Cognitive impairments in poly-drug ketamine users. Addict Behav

2013;38:2661-6. Crossref

16. Tang WK, Morgan CJ, Lau GC, et al.

Psychiatric morbidity in ketamine users attending counselling and youth

outreach services. Subst Abus 2015;36:67-74. Crossref

17. Wang C, Zheng D, Xu J, et al. Brain

damages in ketamine addicts as revealed by magnetic resonance imaging.

Front Neuroanat 2013;7:23. Crossref

18. Narcotics Division, Security Bureau,

HKSAR Government. Evidence of Brain Damage in Chronic Ketamine Users—a

Brain Imaging Study. Available from:

http://www.nd.gov.hk/pdf/Evidence-of-Brain-Damage-in-Chronic-Ketamine-Users_Final-report.pdf.

Accessed 22 Sep 2017.

19. Yeung LY, Wai MS, Fan M, et al.

Hyperphosphorylated tau in the brains of mice and monkeys with long-term

administration of ketamine. Toxicol Lett 2010;193:189-93. Crossref

20. Narcotics Division, Security Bureau,

HKSAR Government. Long-term Ketamine Abuse and Apoptosis in Cynomolgus

Monkeys and Mice. Available from:

http://www.nd.gov.hk/pdf/long_term_ketamine_abuse_apoptosis_in_cynomologus_monkeys_and_mice/final_report_with_all_attachments.pdf.

Accessed 22 Sep 2017.

21. Tan S, Rudd JA, Yew DT. Gene

expression changes in GABA(A) receptors and cognition following chronic

ketamine administration in mice. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e21328. Crossref

22. Mak YT, Lam WP, Lü L, et al. The toxic

effect of ketamine on SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell line and human neuron.

Microsc Res Tech 2010;73:195-201.

23. Wong SW, Lee KF, Wong J, et al.

Dilated common bile ducts mimicking choledochal cysts in ketamine abusers.

Hong Kong Med J 2009;15:53-6.

24. Ng SH, Lee HK, Chan YC, et al. Dilated

common bile ducts in ketamine abusers. Hong Kong Med J 2009;15:157.

25. Cheung TT, Poon RT, Chan AC, et al.

Education and imaging. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic: cholangiopathy in

ketamine user—an emerging new condition. J Gastroenterol Hepatol

2014;29:1663. Crossref

26. Lui KL, Lee WK, Li MK.

Ketamine-induced cholangiopathy. Hong Kong Med J 2014;20:78.e1-2. Crossref

27. Wong GL, Tam YH, Ng CF, et al. Liver

injury is common among chronic abusers of ketamine. Clin Gastroenterol

Hepatol 2014;12:1759-62.e1. Crossref

28. Lo RS, Krishnamoorthy R, Freeman JG,

et al. Cholestasis and biliary dilatation associated with chronic ketamine

abuse: a case series. Singapore Med J 2011;52:e52-5.

29. Ng SH, Tse ML, Ng HW, et al. Emergency

department presentation of ketamine abusers in Hong Kong: a review of 233

cases. Hong Kong Med J 2010;16:6-11.

30. Liu SY, Ng SK, Tam YH, et al. Clinical

pattern and prevalence of upper gastrointestinal toxicity in patients

abusing ketamine. J Dig Dis 2017;18:504-10. Crossref

31. Poon TL, Wong KF, Chan MY, et al.

Upper gastrointestinal problems in inhalational ketamine abusers. J Dig

Dis 2010;11:106-10. Crossref

32. Mak SK, Chan MT, Bower WF, et al.

Lower urinary tract changes in young adults using ketamine. J Urol

2011;186:610-4. Crossref

33. Tam YH, Ng CF, Pang KK, et al.

One-stop clinic for ketamine-associated uropathy: report on service

delivery model, patients’ characteristics and non-invasive investigations

at baseline by a cross-sectional study in a prospective cohort of 318

teenagers and young adults. BJU Int 2014;114:754-60. Crossref

34. Cheung RY, Chan SS, Lee JH, et al.

Urinary symptoms and impaired quality of life in female ketamine users:

persistence after cessation of use. Hong Kong Med J 2011;17:267-73.

35. Ng CF, Chiu PK, Li ML, et al. Clinical

outcomes of augmentation cystoplasty in patients suffering from

ketamine-related bladder contractures. Int Urol Nephrol 2013;45:1245-51. Crossref

36. Ng CF. Editorial comment to possible

pathophysiology of ketamine-related cystitis and associated treatment

strategies. Int J Urol 2015;22:826. Crossref

37. Chu PS, Dasgupta P. Lessons learned

from Asian Urology. BJU Int 2014;114:633. Crossref