Hong Kong Med J 2017 Apr;23(2):150–7 | Epub 24 Feb 2017

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj164993

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Mothers’ attitude to the use of a combined

oral contraceptive pill by their daughters for

menstrual disorders or contraception

KW Yiu, MRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology);

Symphorosa SC Chan, FRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology);

Tony KH Chung, FRANZCOG, FRCOG

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The Chinese University of

Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Symphorosa SC Chan (symphorosa@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Mothers’ attitude may affect use of

combined oral contraceptive pills by their daughters.

We explored Chinese mothers’ knowledge of

and attitudes towards the use of combined oral

contraceptive pills by their daughters for menstrual

disorders or contraception, and evaluate the factors

affecting their attitude.

Methods: This survey was conducted from October

2012 to March 2013, and recruited Chinese women

who attended a gynaecology clinic or accompanied

their daughter to a gynaecology clinic, and who

had one or more daughters aged 10 to 18 years.

They completed a 41-item questionnaire to assess

their knowledge of and attitude towards use of the

combined oral contraceptive pills by their daughters.

The demographic data of the mothers and their

personal experience in using the pills were also

collected.

Results: A total of 300 women with a mean age

of 45.2 (standard deviation, 5.0) years completed

the questionnaire. Only 58.3% of women reported

that they had knowledge about the combined oral

contraceptive pills; among them, a majority (63.3%)

reported that their source of knowledge came from

medical professionals. Of a total possible score of

22, their mean knowledge score for risk, side-effects,

benefits, and contra-indications to use of combined

oral contraceptive pills was only 5.0 (standard

deviation, 4.7). If the medical recommendation

to use an oral contraceptive was to manage their

daughter’s dysmenorrhoea, menorrhagia, acne,

or contraception needs, 32.0%, 39.3%, 21.0% and

29.7%, respectively would accept this advice.

Women who were an ever-user of combined oral

contraceptive pills or who were more knowledgeable

about combined oral contraceptives had a higher

acceptance rate.

Conclusions: Chinese women had a low acceptance

level of using combined oral contraceptive pills as a

legitimate treatment for their daughters. This was

associated with lack of knowledge or a high degree

of uncertainty about their risks and benefits. It is

important that health caregivers provide up-to-date

information about combined oral contraceptive pills

to women and their daughters.

New knowledge added by this study

- Chinese women had a low acceptance level of combined oral contraceptive (COC) pills as a legitimate treatment for their daughters. This was associated with lack of knowledge or a high degree of uncertainty about the risks and benefits of COC use.

- Health caregivers should provide up-to-date information to potential COC users.

Introduction

The combined oral contraceptive (COC) pill is an

effective contraception. It has a very low-risk profile

documented over several decades and its protective

effect on endometrial and ovarian carcinoma has

been well established.1 It is also an effective treatment

for menstrual problems and polycystic ovarian

syndrome,2 3 which are common in adolescents.4 5 6 7

The prevalences of menorrhagia, dysmenorrhoea,

and menstrual symptoms in adolescent girls have

been reported to be 17.9%, 68.7%, and 37.7%,

respectively.4 The prevalence of polycystic ovarian

syndrome in adolescent girls has been reported to

be 16% in those who attended a local paediatric and

adolescent gynaecology clinic.5 Nonetheless, the

use of COC pills in Chinese women has remained

low; only 1% of women of reproductive age (20-49

years) in China used the pills in 2010.8 There are

some obstacles to access although family planning is

a relatively well-funded area of health care in China

and has been implemented for decades. In Hong

Kong, the situation is slightly less unusual. From an

online survey conducted in Hong Kong, 12.6% of

women had used an oral contraceptive in the year

prior to the survey, but many of them had stopped

using it.9 According to the annual report of the

Family Planning Association of Hong Kong in 2014-2015, 22% of the 48 363 clients who practised birth

control, including women who were both married

and unmarried, used an oral contraceptive.10 Only

6% of teenage girls who attended the youth health

care centres used COC pills for contraception.11

Although sex education has been integrated

into the primary and secondary educational

curriculum for many years, efforts to provide

quality sex education have been limited.12 According

to a survey conducted by the Hong Kong SAR

Government, sex education at the junior secondary

school level is limited to an average of 3 to 4 school

hours only.13 Sometimes concepts emphasised

included protection of self and avoidance of sex,

especially prior to marriage.14 The median age of

marriage in Hong Kong is now close to 30 years. It is

notable that Hong Kong has a high rate of therapeutic

abortion that is underestimated by official statistics

because an indeterminate proportion is performed

in mainland China due to cost considerations. In

women attending for their antenatal visit, a high

proportion of 36.5% reported a previous therapeutic

abortion (unpublished data from our institute). This

suggests that women of reproductive age may not

have been educated about contraception. There is

little published information on the use of COC pills

for the management of menstrual problems in Hong

Kong but it is likely to be low. Misconceptions and

myths about COC pills are likely to be the main

obstacles to use. Although extensive high-quality

information about use of COC is currently available

from various sources, many women remain unaware

of the non-contraceptive benefits of COC. They

also have little awareness of the risks of COC.15 For

female adolescents, their decision about whether to

use COC is likely to be influenced by their parents,

especially their mothers, who may be giving advice

to their daughters based on little or erroneous

knowledge. This may lead mothers to make decisions

that are not in their daughter’s best interests.

Focused education about COC may lead to

a more balanced view, both in adolescents and

their mothers. In a study of Korean and Japanese

university students, significant correlation between

knowledge of and positive attitude towards COC

pills was reported.16 Mothers in Asia are also often

involved in their teenage daughters’ decision to

begin sexual relationships, the use of contraceptives, and

even vaccination.17 18 Since the mothers’ attitude may affect use of COC by their daughters, we explored

Chinese mothers’ knowledge of and attitudes

towards such use. Mothers’ knowledge about the

COC pills and factors affecting their attitude were

also evaluated.

Methods

The study was conducted from October 2012 to

March 2013 in the gynaecology clinic of a tertiary

teaching hospital in Hong Kong. Women who

attended the clinic or accompanied a daughter

to the clinic, and who had one or more daughters

aged 10 to 18 years were recruited. Women who

did not speak or read Chinese were excluded. The

participants completed a 41-item questionnaire

to assess their knowledge of and attitude towards

use of COC pills by their daughters. Firstly, they

were asked to self-assess their own knowledge of

the COC pill. The knowledge domain consisted

of 19 items testing their knowledge of the non-contraceptive

health benefits and side-effects of

COC pills, and three items on contra-indications to

use of COC pills. For each item, participants were

asked to respond “yes”, “no”, or “don’t know”. They

were then asked about their attitudes to the use of

COC pills by their daughters aged 10 to 18 years for the

management of dysmenorrhoea, menorrhagia, acne,

or as a contraceptive. They were asked to respond

from “strongly agree”, “agree”, “disagree”, to “strongly

disagree”. Reasons for agreeing or disagreeing with

the use of COC pills and the appropriate age or

life-events for using COC pills by their daughters

were also asked. Finally, demographic data and

their personal experience in using COC pills were

collected. Knowledge score and uncertainty score

were calculated for the participants based on their

response15 16—knowledge score was defined as the score of correct answers with 1 score given for

each correct answer (ie range from 0-22); a “don’t

know” reply would create the uncertainty score. The

participants provided written informed consent,

and approval was obtained from the local ethics

committee (CRE-2012.186).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise

participants’ demographic information. Association

between participant characteristics and overall

attitude was explored using Chi squared and

independent-samples t test. A P value of <0.05 was

considered statistically significant. All statistical

analyses were conducted using the SPSS (Windows

version 18.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], United States). Assuming

that 50% of the women accepted the use of COC pills

by their daughters with an accepted error of 0.05%,

278 women were required. An additional 10% was

recruited to prepare for an incomplete questionnaire.

Results

Apart from 150 women who were excluded because

they did not have a daughter aged 10 to 18 years, a

total of 317 women were invited to participate; 302

agreed and 300 (94.6%) completed the questionnaire.

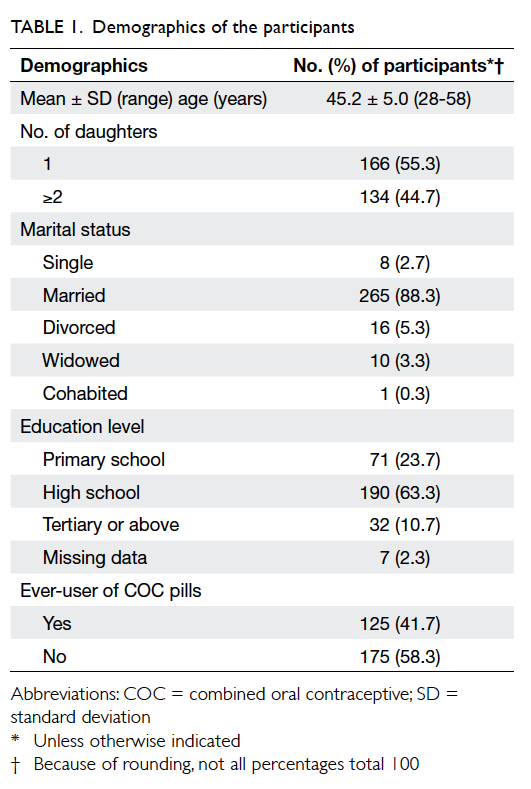

Demographic characteristics of the participants are

shown in Table 1. Their mean age was 45.2 years (range, 28-58 years). The median number of daughters

was one and most participants (88.3%) were married.

Most (>70%) had high school education. In all, 125

(41.7%) were ever-users of COC pills, including both

current and ex-users. Overall, 175 (58.3%) reported

that they had knowledge about the COC pills, while

125 (41.7%) reported no knowledge.

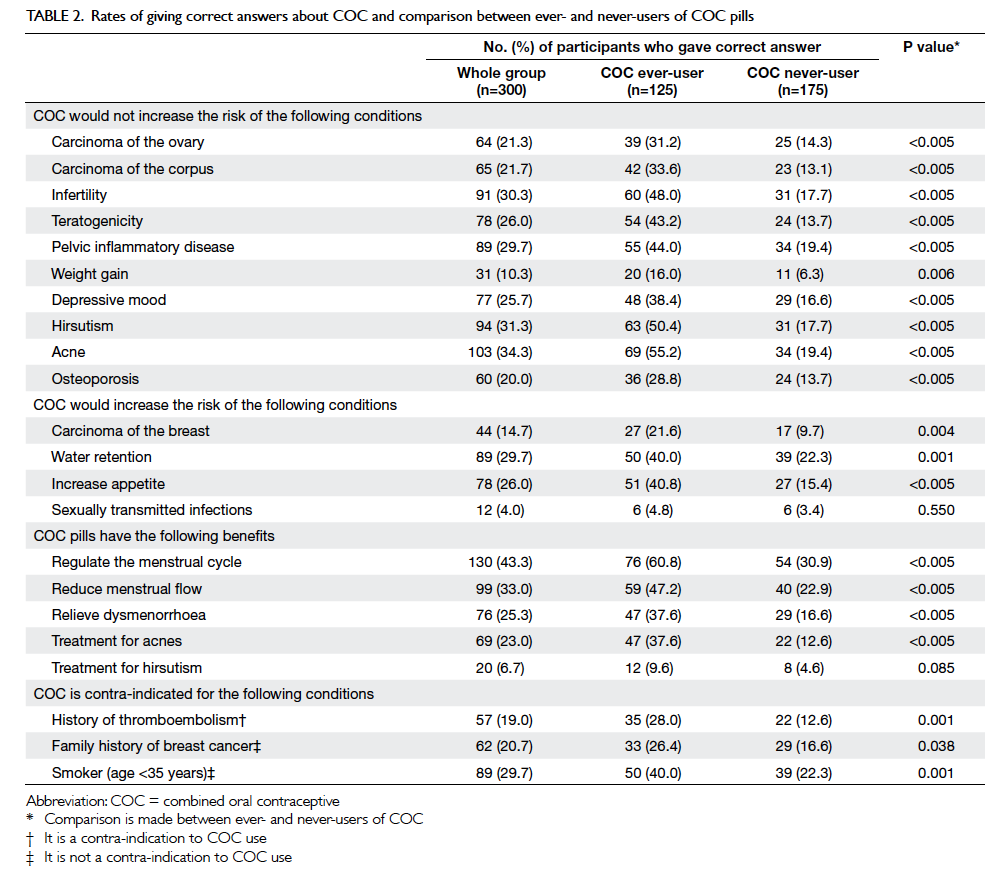

The rates of giving correct answers about the

COC pill and the comparison between ever- and

never-users of COC pills are shown in Table 2. Of

a total possible score of 22, the mean (± standard

deviation) knowledge score of all the participants was

5.0 ± 4.7. Of all the participants, only approximately

20% of the mothers correctly answered that COC

pills would not cause carcinoma of ovary and

corpus; 26.0%, 29.7%, and 30.3% respectively

correctly answered that COC pills did not have

proven teratogenicity, cause pelvic inflammatory

disease and infertility; 10.3% knew that COC pills

would not cause weight gain and 25.7% answered

that COC pills would not lead to a depressive mood.

In all, 43.3%, 33.0%, and 25.3% knew that COC pills

had the benefits of regulating the menstrual cycle,

decreasing menstrual flow, and helping to relieve

dysmenorrhoea, respectively. Moreover only 20%

knew that the COC pills are not contra-indicated

in people with a family history of breast cancer

but is contra-indicated in thromboembolism. The

knowledge score of the 175 women who responded

to have knowledge of the COC pills was significantly

higher than those who reported lack of knowledge

(8.0 ± 4.4 vs 3.0 ± 3.7; P<0.001). Among those who

declared they had knowledge about the use of COC

pills, their sources of knowledge were from medical

professional (63.3%), media (30.3%), friends (24.6%),

family members (6.9%), school (2.9%), and others

(1%).

Table 2. Rates of giving correct answers about COC and comparison between ever- and never-users of COC pills

The rate of responding “uncertain” to the health

benefit, side-effects, or contra-indications of COC

use ranged from 43.7% to 71.0% for each item. The

mean uncertainty score among all participants was

13.0 ± 7.6. The uncertainty score was significantly

higher in participants who reported to have lack of

knowledge when compared with those reported to

have knowledge about COC pills (15.6 ± 7.1 vs 9.1 ±

6.7; P<0.001).

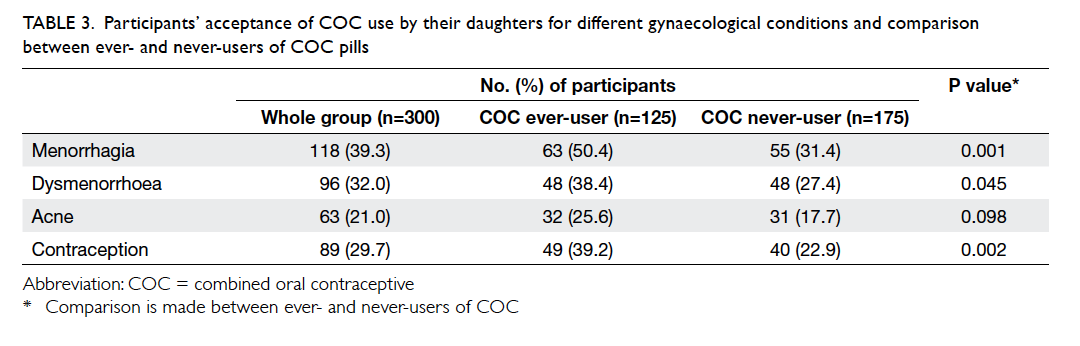

Among the ever-users, 43 (34%), five (4%), and

96 (77%) women reported that COC pills had been

used to manage their own menstrual problems, acne

problems, and as contraception, respectively. Table 3 lists the participants’ acceptance rate of COC use by their daughters in different gynaecological

conditions and the comparison between ever- and

never-users of COC pills. More ever-users than

never-users accepted the use of COC for their

daughter’s gynaecological indications. Participants

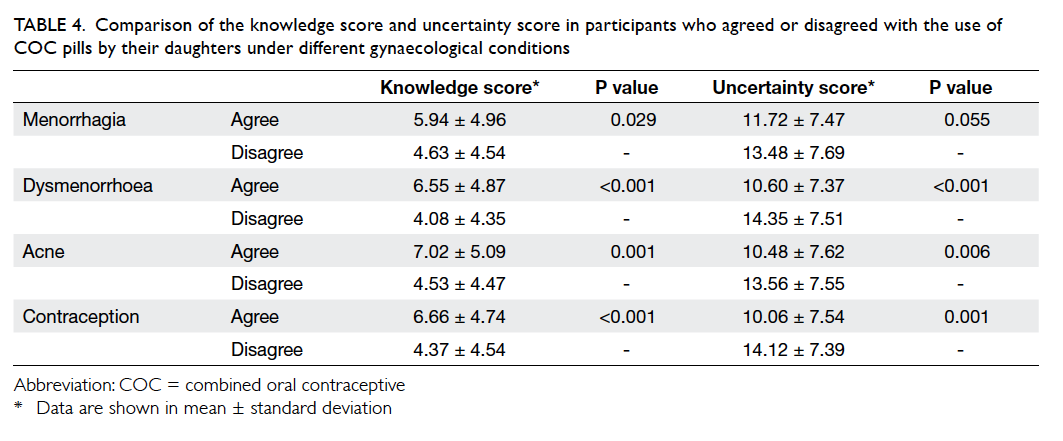

who accepted their daughter’s use of COC also had a

higher knowledge score and lower uncertainty score

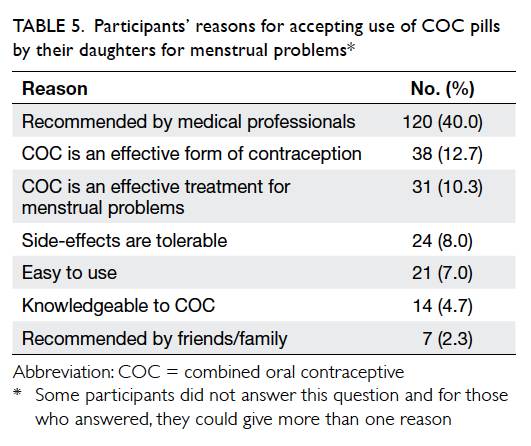

(Table 4). Table 5 shows the participants’ reasons for accepting use of COC pills by their daughters.

Recommendation by medical professionals was the

major reason, followed by the knowledge that COC

pills provided effective contraception.

Table 3. Participants’ acceptance of COC use by their daughters for different gynaecological conditions and comparison between ever- and never-users of COC pills

Table 4. Comparison of the knowledge score and uncertainty score in participants who agreed or disagreed with the use of COC pills by their daughters under different gynaecological conditions

Table 5. Participants’ reasons for accepting use of COC pills by their daughters for menstrual problems

Age, education level, and whether they had

previous experience of side-effects of COC pills were

not associated with participants’ acceptance of COC

use by their daughters. Among the 125 ever-users of

COC pills, 65 (52.0%) reported they had experienced

side-effects, including weight gain (n=45), fluid

retention (n=25), headache (n=12), increase in

appetite (n=8), mode disturbance (n=8), and acne

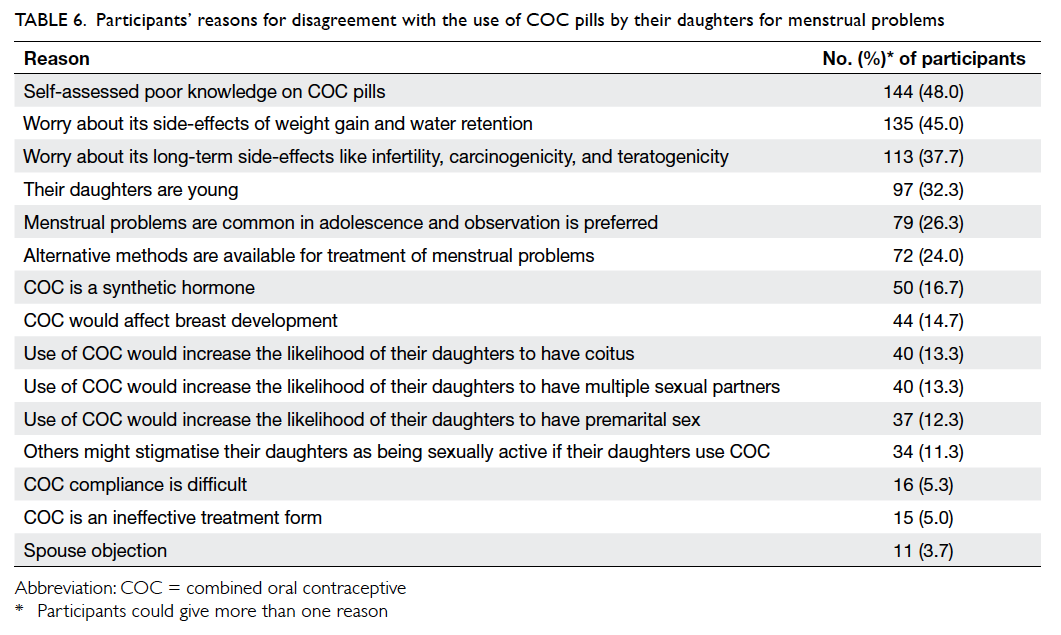

(n=4). Table 6 lists the reasons for disagreement with the use of COC pills by their daughters for menstrual

problems. Finally, only 71 (23.6%) participants

thought that the use of COC pills was appropriate in

girls aged 12 to 18 years.

Table 6. Participants’ reasons for disagreement with the use of COC pills by their daughters for menstrual problems

Discussion

Our study highlights a notable lack of knowledge

about the use of COC pills in many Hong Kong

Chinese mothers. Many were uncertain or had

erroneous beliefs about the use of COC pills. They

believed that such usage would lead to cancers,

fetal deformity, and cause infertility and pelvic

inflammatory disease. These misconceptions and

uncertainties may further reinforce their non-acceptance

of the COC pills as an appropriate

medication for their daughters. This inevitably often

leads to suboptimal treatment for their daughters.

Fear of increased risk of cancer is an important

reason for low acceptance of COC pills and only

22% of our participants thought it did not increase

the risk for carcinoma of ovary or uterus. More

than 60% of the participants were uncertain about

the risk of cancer with the use of COC pills (results

not shown). Research has shown that contraceptives

have a significantly protective effect on carcinoma

of ovary and corpus uteri.19 20 In fact, a collaborative re-analysis of individual data from 53 297 women with

breast cancer and 100 239 women without breast

cancer from 54 epidemiological studies revealed

that while women were taking COC pills and in the

10 years after stopping, there was a small increase

in the relative risk of breast cancer.21 There was,

however, no significant excess risk of having breast

cancer diagnosed ≥10 years after stopping

use of COC pills. The breast cancer incidence rises

steeply with age. The estimated excess number of

cancers diagnosed in the period between starting

use and 10 years after stopping increases with age

at last use. The estimated excess number of breast

cancers diagnosed up to 10 years after stopping

use from the age of 16 to 19 years among 10 000

women has been reported to be 0.5 (95% confidence

interval, 0.3-0.7) only.21 The Nurses’ Health Study

with 121 701 participants followed up for 36 years

revealed that longer duration of COC use was

strongly associated with premature mortality due

to breast cancer.22 Another highlight was that only

20.7% of our participants knew that a family history

of breast cancer was not a contra-indication to use of

COC pills.

Another common misconception is that the

use of COC pills can lead to future subfertility.

The COC pill preserves fertility by diminishing the

risk of ectopic pregnancy.23 According to a review,

1-year pregnancy rates after discontinuation of COC

ranged from 79% to 96%, similar to those reported

following discontinuation of barrier methods or no

contraception.24 Moreover, the progestogen effect of

COC pills results in production of thick, tenacious

cervical mucus that resists penetration by bacteria

and spermatozoa and reduces the risk of upper

genital tract infection. Use of COC pills was also

quoted to be protective against symptomatic pelvic

inflammatory disease, with a 50% reduction in rate

of hospitalisation for the disease, with itself being a

risk factor for subfertility.25 The COC pill does not

protect against sexually transmitted infections. On

the other hand, there is no evidence to support the

notion that the use of COC pills is associated with

high-risk sexual behaviour in adolescents, which is a

very common fear among Hong Kong mothers.

Primary dysmenorrhoea is prevalent during

adolescence. Approximately 6.4% of adolescents or

29% of those reporting severe dysmenorrhoea seek

help from a physician.4 A review and meta-analysis

of five trials of the use of COC pills concluded that

it was more effective than placebo in managing

dysmenorrhoea.2 One of the most common problems

reported by adolescents is irregular and/or profuse

menstruation. The COC pill is also effective in

treating and preventing heavy menstrual bleeding. In

our study, only 25% to 43% of the participants knew

that it is an appropriate treatment for menstrual

problems and 50% were uncertain.

The fear of side-effects often leads to reluctance

to using new treatments.18 In many cases, such fears

are often unfounded. In our study, participants

believed that weight gain and depressive mood were

side-effects of COC pills, although pooled analysis

of a placebo-controlled trial showed no difference

in weight gain.26 Furthermore, depressive symptoms

are common in adolescence.27 In a randomised

controlled study, there was no difference in mood

changes throughout the menstrual cycle between

COC users and non-users.28 In a prospective study

of 43 adolescents, subjects anticipated more side-effects

than they actually experienced after 6 months

of taking COC pills.29

It is important to provide correct information

to women and their teenage daughters if they are

contemplating the use of COC pills. In our study,

40% of participants indicated that recommendation

from a medical professional was a critical factor in

their acceptance of the use of COC pills by their

daughters.

Only 19% of participants were aware that

thromboembolism is a contra-indication to COC

use. Venous thromboembolism in Asians has been

reported to be low.30 A recent case-control study

confirmed that current exposure to any COC poses

a 3-times higher risk of venous thromboembolism

compared with no exposure in the previous year.31

The risk is higher with COC pills containing

desogestrel (odds ratio, 4.3), gestodene (3.6),

drospirenone (4.1), and cyproterone (4.3) than the

second-generation COC pills with levonorgestrel

(2.4) and norgestimate (2.5).31 The risk of venous

thromboembolism is also increased for COC users

with a family history of venous thromboembolism.32

Clinicians should assess the woman’s personal and

family history of thromboembolism, and provide

information about the warning symptoms of

venous thromboembolism before prescribing a

new generation pill. As recommended by the World

Health Organization, the COC pill is not contra-indicated

in smokers <35 years old33;

approximately 30% of our participants answered this

correctly.

This study has several limitations. First,

there may be selection bias as subjects were

women who presented to the gynaecology clinic or

accompanied their daughter to a gynaecology clinic

for a gynaecological problem. The results may not be

generalised to the whole population of Hong Kong.

Second, the questionnaire was not validated and the

questions did not include all aspects of the use of

COC pills. Third, we relied on women’s self-reported

use of COC pills and could not verify the information.

Despite these, the questionnaire included the most

widely studied aspects of non-contraceptive benefits

and risks of the COC pill and knowledge score

or uncertainty score have been used in previous

literature.15 16 Although this study was conducted in only one centre and in Chinese women only, it helps

clinicians to understand the low levels of acceptance

of and compliance with prescribed COC pills.

The degree of misconception among Hong

Kong mothers about COC use is of concern. Hong

Kong has a well-developed education system with

many highly regarded universities. The reported

limited sex education in schools may be responsible

for this knowledge gap of Hong Kong mothers.13 This

may in turn have an impact on the advice they give

their daughters, who are usually compliant with their

mother’s wishes. Specific training in communication

and counselling skills should be provided to health

care professionals when promoting sexual health to

women and adolescents.34

Conclusions

Our study found that the Hong Kong Chinese women

who attended a gynaecology clinic of a tertiary centre

had a low acceptance rate of the use of COC pills by

their daughters. This low acceptance was associated

with a lack of knowledge and misconception of the

risks and benefits of the COC pills. Such ignorance

will exert an adverse influence on the choice of

treatment for many gynaecological problems in

teenage daughters.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Vessey M, Painter R. Oral contraceptive use and cancer.

Findings in a large cohort study, 1968-2004. Br J Cancer

2006;95:385-9. Crossref

2. Proctor ML, Roberts H, Farquhar CM. Combined

oral contraceptive pill (OCP) as treatment for

primary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2001;(4):CD002120.

3. Nader S, Diamanti-Kandarakis E. Polycystic ovary

syndrome, oral contraceptives and metabolic issues: new

perspectives and a unifying hypothesis. Hum Reprod

2007;22:317-22. Crossref

4. Chan SS, Yiu KW, Yuen PM, Sahota DS, Chung TK.

Menstrual problems and health-seeking behaviour in

Hong Kong Chinese girls. Hong Kong Med J 2009;15:18-23.

5. Chung PW, Chan SS, Yiu KW, Lao TT, Chung TK.

Menstrual disorders in a Paediatric and Adolescent

Gynaecology Clinic: patient presentations and longitudinal

outcomes. Hong Kong Med J 2011;17:391-7.

6. Esmaelizadeh S, Delavar MA, Amiri M, Khafri S, Pasha

NG. Polycystic ovary syndrome in Iranian adolescents. Int

J Adolesc Med Health 2014;26:559-65. Crossref

7. Christensen SB, Black MH, Smith N, et al. Prevalence of

polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescents. Fertil Steril

2013;100:470-7. Crossref

8. Wang C. Trends in contraceptive use and determinants of

choice in China: 1980-2010. Contraception 2012;85:570-9. Crossref

9. Lo SS, Fan SY. Acceptability of the combined oral

contraceptive pill among Hong Kong women. Hong Kong

Med J 2016;22:231-6.

10. The Family Planning Association of Hong Kong. 2014-2015 Annual report. Available from: http://www.famplan.org.hk/fpahk/en/template1.asp?style=template1.asp&content=about/annualreport.asp. Accessed 28 Apr 2016.

11. The Family Planning Association of Hong Kong. Youth

sexuality in Hong Kong secondary school survey. Available

from: http://www.famplan.org.hk/fpahk/en/template1.asp?content=info/research.asp. Accessed 28 Apr 2016.

12. Che FS. A study of the implementation of sex education in

Hong Kong secondary schools. Sex Educ 2005;5:281-94. Crossref

13. Survey of life skills-based education on HIV/AIDS at

junior level of secondary schools in Hong Kong. Red

Ribbon Centre, Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR

Government; 2014.

14. Wong WC, Lee A, Tsang KK, Lynn H. The impact of AIDS/sex education by schools or family doctors on Hong Kong Chinese adolescents. Psychol Health Med 2006;11:108-16. Crossref

15. Voqt C, Schaefer M. Disparities in knowledge and interest

about benefits and risks of combined oral contraceptives.

Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2011;16:183-93. Crossref

16. Lim HJ, Lee MS, Cho YH, Kazumi U. A comparative study

of knowledge about and attitudes toward the combined

oral contraceptives among Korean and Japanese university

students. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2004;13:741-7. Crossref

17. Bachar R, Yogev Y, Fisher M, Geva A, Blumberg G, Kaplan

B. Attitudes of mothers toward their daughters’ use of

contraceptives in Israel. Contraception 2002;66:117-20. Crossref

18. Chan SS, Cheung TH, Lo WK, Chung TK. Women’s

attitudes on human papillomavirus vaccination to their

daughters. J Adolesc Health 2007;41:204-7. Crossref

19. Cibula D, Gompel A, Mueck AO, et al. Hormonal

contraception and risk of cancer. Hum Reprod Update

2010;16:631-50. Crossref

20. Bitzer J. Oral contraceptives in adolescent women. Best

Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;27:77-89. Crossref

21. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer.

Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative

reanalysis of individual data on 53 297 women with breast

cancer and 100 239 women without breast cancer from 54

epidemiological studies. Lancet 1996;347:1713-27. Crossref

22. Charlton BM, Rich-Edwards JW, Colditz GA, et al. Oral

contraceptive use and mortality after 36 years of follow-up

in the Nurses’ Health Study: prospective cohort study. BMJ

2014;349:g6356. Crossref

23. Burkman R, Schlesselman JJ, Zieman M. Safety concerns

and health benefits associated with oral contraception. Am

J Obstet Gynecol 2004;190 (4 Suppl):S5-22. Crossref

24. Mansour D, Gemzell-Dianielsson K, Inki P, Jensen

JT. Fertility after discontinuation of contraception: a

comprehensive review of the literature. Contraception

2011;84:465-77. Crossref

25. Guillebaud J, MacGregor A. Contraception: your questions

answered. 6th ed. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2013.

26. Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, Carayon F, Schulz KF,

Helmerhorst FM. Combination contraceptives: effects on

weight. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;(1):CD003987. Crossref

27. Saluja G, Iachan R, Scheidt PC, Overpeck MD, Sun W,

Giedd JN. Prevalence of and risk factors for depressive

symptoms among young adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc

Med 2004;158:760-5. Crossref

28. Walker A, Bancroft J. Relationship between premenstrual

symptoms and oral contraceptive use: a controlled study.

Psychosom Med 1990;52:86-96. Crossref

29. Rosenthal SL, Cotton S, Ready JN, Potter LS, Succop

PA. Adolescents’ attitudes and experiences regarding

levonorgestrel 100 mcg/ethinyl estradiol 20 mcg. J Pediatr

Adolesc Gynecol 2002;15:301-5. Crossref

30. Lee WS, Kim KI, Lee HJ, Kyung HS, Seo SS. The incidence

of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis after

knee arthroplasty in Asians remains low: a meta-analysis.

Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013;471:1523-32. Crossref

31. Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J. Use

of combined oral contraceptives and risk of venous

thromboembolism: nested case-control studies using the

QResearch and CPRD databases. BMJ 2015;350:h2135. Crossref

32. Zöller B, Ohlsson H, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Family

history of venous thromboembolism is a risk factor for

venous thromboembolism in combined oral contraceptive

users: a nationwide case-control study. Thromb J

2015;13:34. Crossref

33. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use. 5th ed.

Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

34. Yip BH, Sheng XT, Chan VW, Wong LH, Lee SW, Abraham

AA. ‘Let’s talk about sex’—a knowledge, attitudes and

practice study among paediatric nurses about teen sexual

health in Hong Kong. J Clin Nurs 2015;24:2591-600. Crossref