Hong Kong Med J 2017 Apr;23(2):158–67 | Epub 17 Mar 2017

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj165014

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Improving medication safety and diabetes management in Hong Kong: a multidisciplinary

approach

Agnes YS Chung, BPharm1;

Shweta Anand, BDS1;

Ian CK Wong, PhD2;

Kathryn CB Tan, MD, MBBCH3;

Christine FF Wong, PharmD4;

William CM Chui, MSc4;

Esther W Chan, PhD1

1 Department of Pharmacology and Pharmacy, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

2 Research Department of Practice and Policy, School of Pharmacy,

University College London, United Kingdom

3 Department of Medicine, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

4 Department of Pharmacy, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Esther W Chan (ewchan@hku.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Patients with diabetes often require

complex medication regimens. The positive impact

of pharmacists on improving diabetes management

or its co-morbidities has been recognised worldwide.

This study aimed to characterise drug-related

problems among diabetic patients in Hong Kong

and their clinical significance, and to explore the

role of pharmacists in the multidisciplinary diabetes

management team by evaluating the outcome of

their clinical interventions.

Methods: An observational study was conducted at

the Diabetes Clinic of a public hospital in Hong Kong

from October 2012 to March 2014. Following weekly

screening, and prior to the doctor’s consultation,

selected high-risk patients were interviewed by

a pharmacist for medication reconciliation and

review. Drug-related problems were identified and

documented by the pharmacist who presented

clinical recommendations to doctors to optimise

a patient’s drug regimen and resolve or prevent

potential drug-related problems.

Results: A total of 522 patients were analysed and

417 drug-related problems were identified. The

incidence of patients with drug-related problems

was 62.8% with a mean of 0.9 (standard deviation,

0.6) drug-related problems per patient. The most

common categories of drug-related problems were

associated with dosing (43.9%), drug choice (17.3%),

and non-allergic adverse reactions (15.6%). Drugs

most frequently involved targeted the endocrine

or cardiovascular system. The majority (71.9%) of

drug-related problems were of moderate clinical

significance and 28.1% were considered minor

problems. Drug-related problems were totally solved

(50.1%) and partially solved (11.0%) by doctors’

acceptance of pharmacist recommendations, or

received acknowledgement from doctors (5.5%).

Conclusions: Pharmacists, in collaboration with

the multidisciplinary team, demonstrated a positive

impact by identifying, resolving, and preventing

drug-related problems in patients with diabetes.

Further plans for sustaining pharmacy service in

the Diabetes Clinic would enable further studies

to explore the long-term impact of pharmacists in

improving patients’ clinical outcomes in diabetes

management.

New knowledge added by this study

- Pharmacists make an important contribution to the identification, resolution, and prevention of drug-related problems by medication reconciliation and review. Most problems were related to dosing with moderate clinical significance according to Dean and Barber’s validated scale for scoring medication errors. Over half of the clinical interventions initiated by pharmacists were accepted or acknowledged by doctors to improve medication management.

- Collaboration between pharmacists and other health care professionals is valuable for the improvement of medication safety in the management of diabetes.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic disease that is

prevalent worldwide.1 Patients with diabetes often

require complex medication regimens and are likely

to develop multiple irreversible complications that

significantly worsen their quality of life.2 Effective

diabetes management requires collaboration among

health care professionals in a multidisciplinary

diabetes management team (DMT). Pharmacists, as

a part of the DMT, are well positioned to optimise

pharmacological treatment, educate patients about

diabetes management, and promote medication

compliance.3

The major role of a pharmacist in a DMT is

to conduct medication reconciliation (MR) and

medication review—MR is the process of comparing

a patient’s prescriptions with all their usual

medications and identifying the most complete and

updated medication history4; whereas medication

review aims to review a patient’s medical and drug

history, assess their current prescriptions, and

ascertain their drug knowledge and compliance.5

This enables pharmacists to identify drug-related

problems (DRPs) that can actually or potentially

interfere with optimum health outcomes in specific

patients.6 7 Polypharmacy (concurrent use of

multiple medications) is commonly seen in people

with chronic diseases which could lead to potential

DRPs.8 9 These DRPs might be overlooked by

prescribers and interfere with diabetes management.

In several overseas studies, pharmacists have

implemented timely interventions to resolve or

prevent DRPs by offering recommendations to

prescribers, with an acceptance rate of over 60%.10 11 12 13

The positive impact of pharmacists in improving

diabetes management or its co-morbidities has

also been recognised by interventional and controlled

observational studies worldwide.14 Greater overall

improvement in glycosylated haemoglobin, fasting

plasma glucose, blood pressure, cholesterol

levels, renal outcomes, and medication adherence

has been demonstrated in patients who received

pharmacist-led diabetes services compared with the

standard care.12 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Few studies, however, have been

conducted in Hong Kong.17 29 In view of inadequate available data and potential for expansion of local

pharmacy services, more studies are required to

investigate the future development of a sustainable

diabetes service provided by pharmacists.

This study aimed to characterise DRPs

among Chinese diabetic out-patients, and to

define the clinical significance and outcome of

pharmacist interventions; thereby highlighting

their contribution to the detection, resolution, and

prevention of DRPs to improve medication safety

and diabetes management.

Methods

Study design and setting

An observational study was conducted weekly in

the Diabetes Clinic at Queen Mary Hospital (QMH)

from October 2012 to March 2014. The study

protocol was approved by the Institutional Review

Board of the University of Hong Kong (HKU)/Hospital Authority (HA) Hong Kong West Cluster.

Informed consent was not required for the study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients were included if they were at ‘high risk’ due

to their multiple disease state and complex drug

regimen and if they fulfilled the following criteria:

- Aged ≥65 years (elderly patients are considered having high risk for DRPs since they usually take more drugs than younger patients)

- Taking five or more medications including all routes of administration, or over-the-counter medications (regular or as needed)

- Taking medications that have a low therapeutic index or require monitoring

- Attending multiple specialist clinics

Nursing home residents were excluded due

to their relatively low risk for non-compliance,

compared with community-dwelling elderly patients.

Procedure and materials

The day before the scheduled weekly clinic

consultation, two researchers screened the medical

history, previous consultation notes, current

medications, and latest laboratory results of Chinese

elderly patients with diabetes to select high-risk

patients. Selected patient records were printed and

prepared for quick reference during the medication

interview. To facilitate data collection, a memo was

attached to the patient’s records to indicate patient

selection.

Two pharmacists from QMH and one from the

HKU attended the clinic on alternate Wednesdays to

compile a thorough medication history from selected

patients and conduct an independent medication

review prior to the medical consultation. During the

review, pharmacists also recorded medications not

shown in the Clinical Management System (CMS),

such as drugs prescribed by general practitioners

(GPs), over-the-counter products, vitamins, and

herbal supplements.

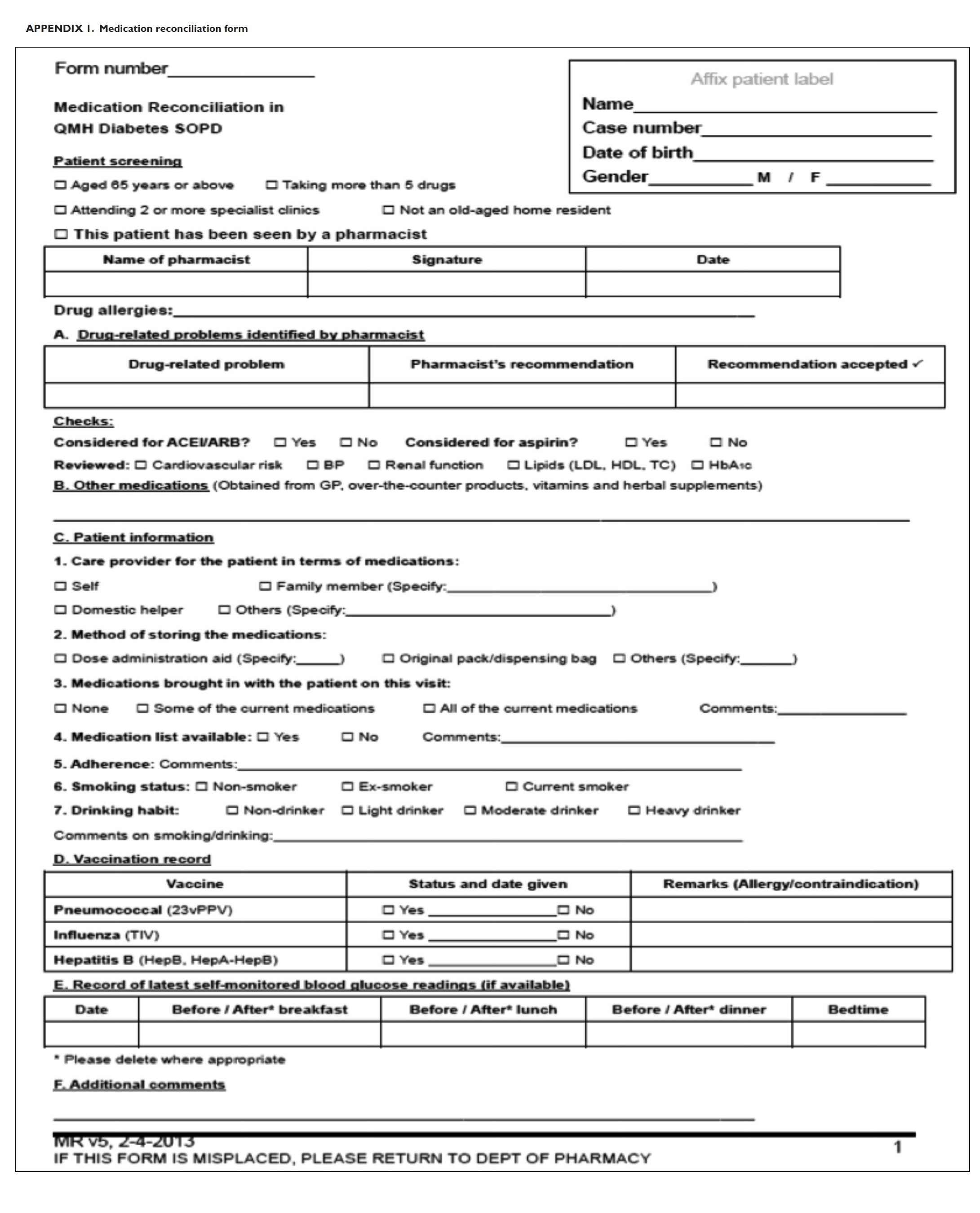

A MR form (Appendix 1) was then completed

by pharmacists, documenting the identified DRPs

and formulating an intervention proposal. The MR

forms were collected following medical consultation,

either on the same day or within the next few days.

Pharmacist intervention

For the selected high-risk patients, pharmacists

reviewed the patient’s drug regimen and made

recommendations to doctors for adjustment,

provided doctors with an updated drug list after MR,

suggested a need to further investigate a patient’s

condition, provided drug education to patients

and caregivers, reinforced the importance of drug

compliance to patients, and suggested lifestyle

modifications such as dietary control.

Drug-related problems were identified

from the completed MR forms, and pharmacist

recommendations were collected for analysis. The

CMS was checked for outcome of intervention.

Data collection

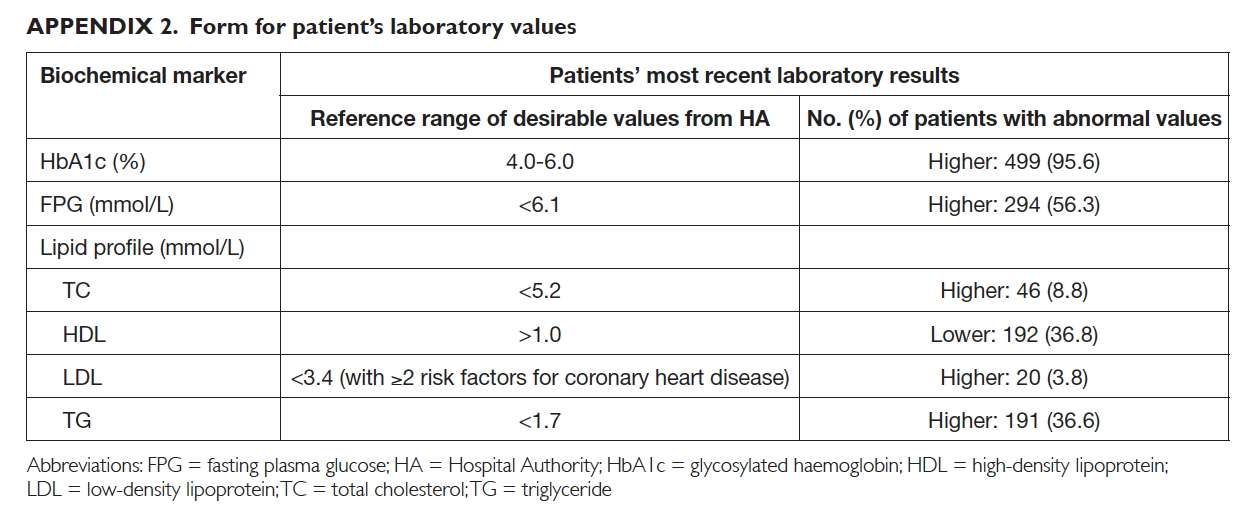

Demographic data—for example, age, gender,

drug allergy status, number of regular medications

obtained from the HA clinics, and the most

current laboratory results, including glycosylated

haemoglobin, fasting plasma glucose, and lipids

(Appendix 2)—were retrieved from the CMS.

Additional information in terms of medication,

drug storage methods, smoking status, drinking

habits, vaccination record, and latest readings from

self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) was also

collected.

Data analysis

Demographic data were tabulated as frequency and

percentage using Microsoft Excel 2010. Primary

outcomes included the frequency and categories of

DRPs, drug classes involved, clinical significance of

DRPs, and outcome of pharmacist interventions.

The incidence of DRPs was also calculated as the

percentage of patients with at least one DRP.

Definition and classification of drug-related problems

Using the Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe

(PCNE) classification system for DRPs V5.01, DRPs

were categorised as ‘adverse reactions’, ‘drug choice

problem’, ‘dosing problem’, ‘drug use problem’,

‘interactions’, or ‘others’.7 This is an established system that has been revised several times with tested

validity and reproducibility11 31 and has been used in many studies.9 32 33 When a single drug was associated

with more than one possible DRP category, the one

that best described the clinical scenario was chosen.

Drugs involved in DRPs were categorised according

to their British National Formulary classification.34

The clinical significance of DRPs was assessed

to determine their actual or potential consequence

for patient health outcomes. Using a validated

scale,35 four independent reviewers (two pharmacists

and two doctors) scored the severity of each DRP

from 0 (without potential effects on the patient)

to 10 (lead to a fatal event). A mean score of <3

indicated a minor problem (very unlikely to cause

adverse effects), 3 to 7 indicated a moderate problem

(likely to cause some adverse effects or interfere

with therapeutic goals), and >7 indicated a

severe DRP that could likely cause death or lasting

impairment.

To evaluate prescribers’ acceptance level,

the outcome of pharmacist interventions was

categorised as ‘not known’, ‘solved’, ‘partially solved’,

or ‘not solved’ according to PCNE classification

V5.01.7

Results

Patient demographics and characteristics

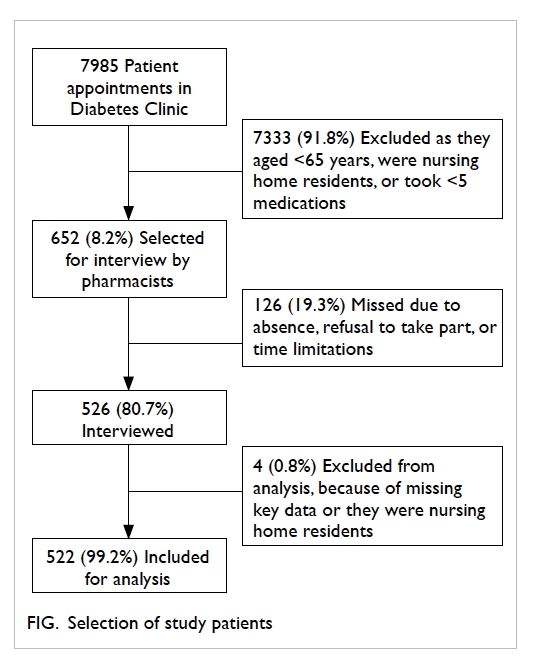

During the study period, a total of 652 patients

were included based on the selection criteria; 526

(80.7%) were interviewed, of whom 522 (99.2%) were

analysed (Fig).

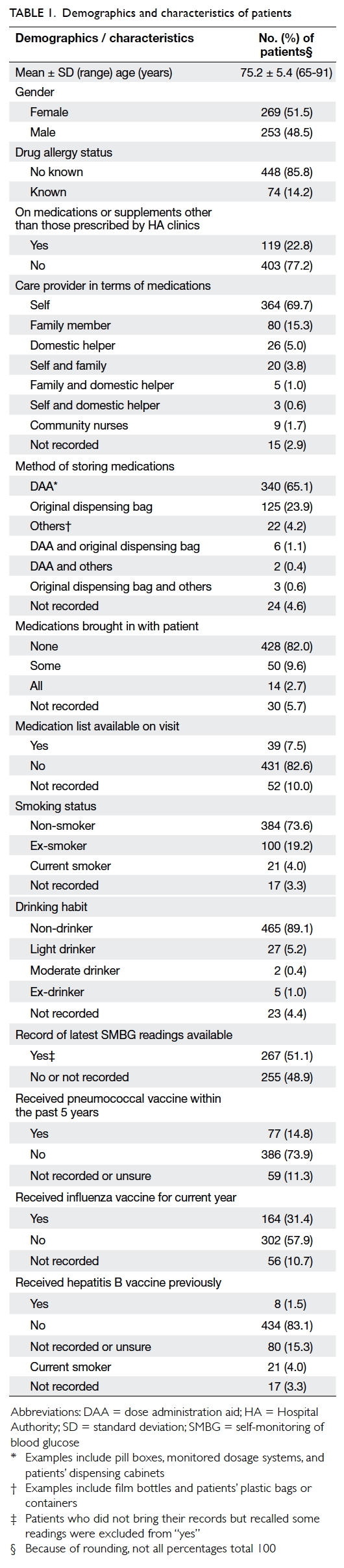

The mean (± standard deviation) age of the 522

patients was 75.2 ± 5.4 years (range, 65-91 years).

The number of prescribed regular HA medications

ranged from 5 to 17 with a mean of 9 ± 2. The

demographics and characteristics of patients are

shown in Table 1.

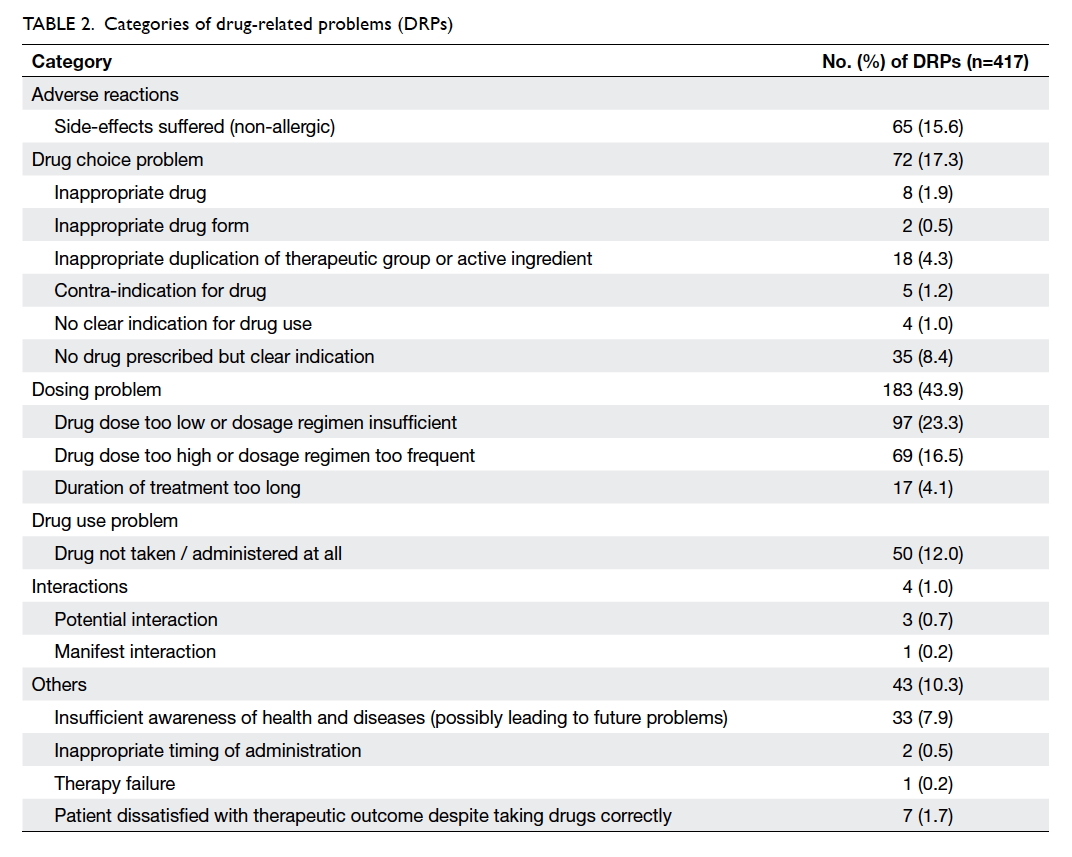

Categories of drug-related problems

A total of 417 DRPs were identified. Among the 522

patients analysed, 328 (62.8%) had at least one DRP

and the mean number of DRPs per patient was 0.9

± 0.6. The most prevalent DRP category was related

to dosing (n=183, 43.9%), followed by drug choice

(n=72, 17.3%) and non-allergic adverse reaction

(n=65, 15.6%). The subcategories of each of them

are listed in Table 2.

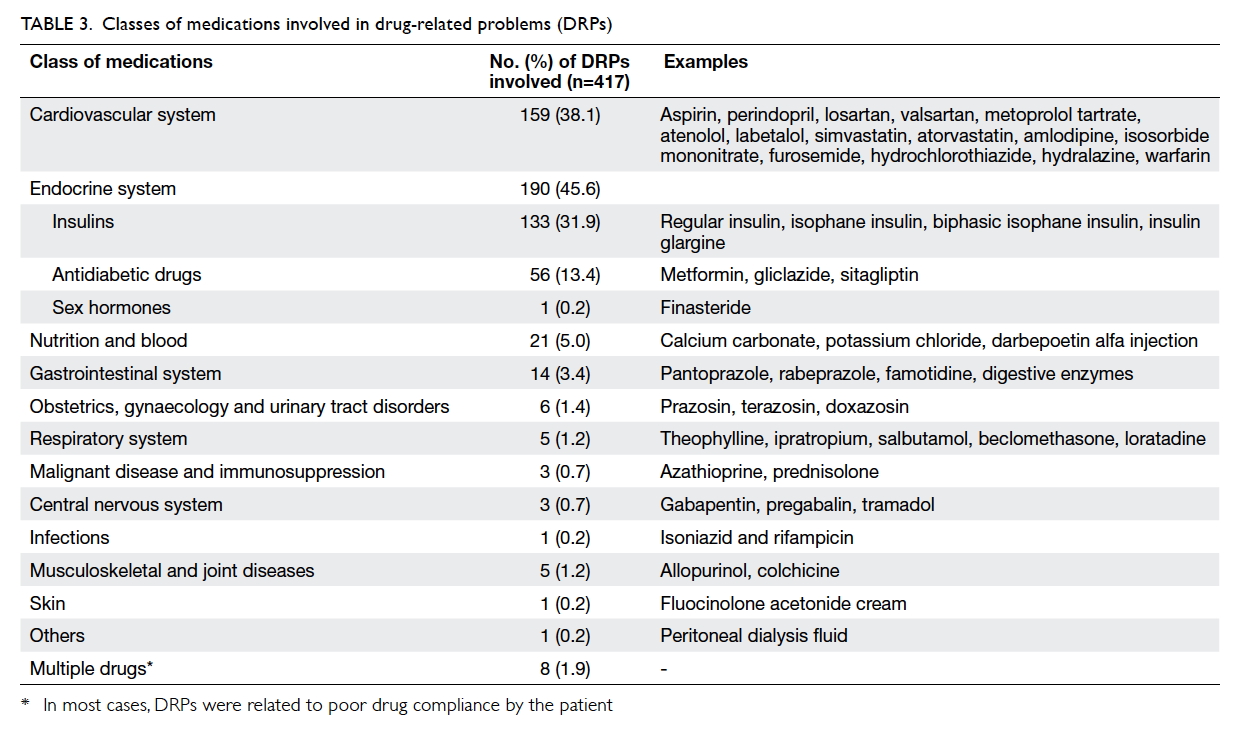

Classes of medications involved in drug-related problems

The most common classes of medication involved

were those targeting the endocrine system with 190

(45.6%) DRPs, followed by cardiovascular system

with 159 (38.1%) DRPs (Table 3).

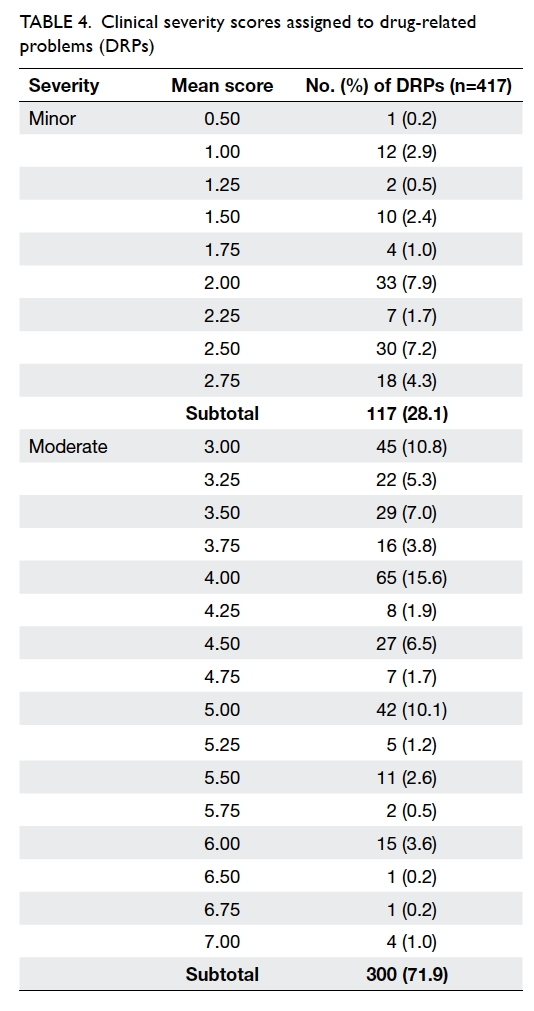

Clinical significance of drug-related problems

The mean clinical severity scores assigned to DRPs

ranged from 0.50 to 7.00. The majority of DRPs

(n=300, 71.9%) were classified as moderate with the

remainder (n=117, 28.1%) considered minor. No

clinically severe DRP was identified (Table 4).

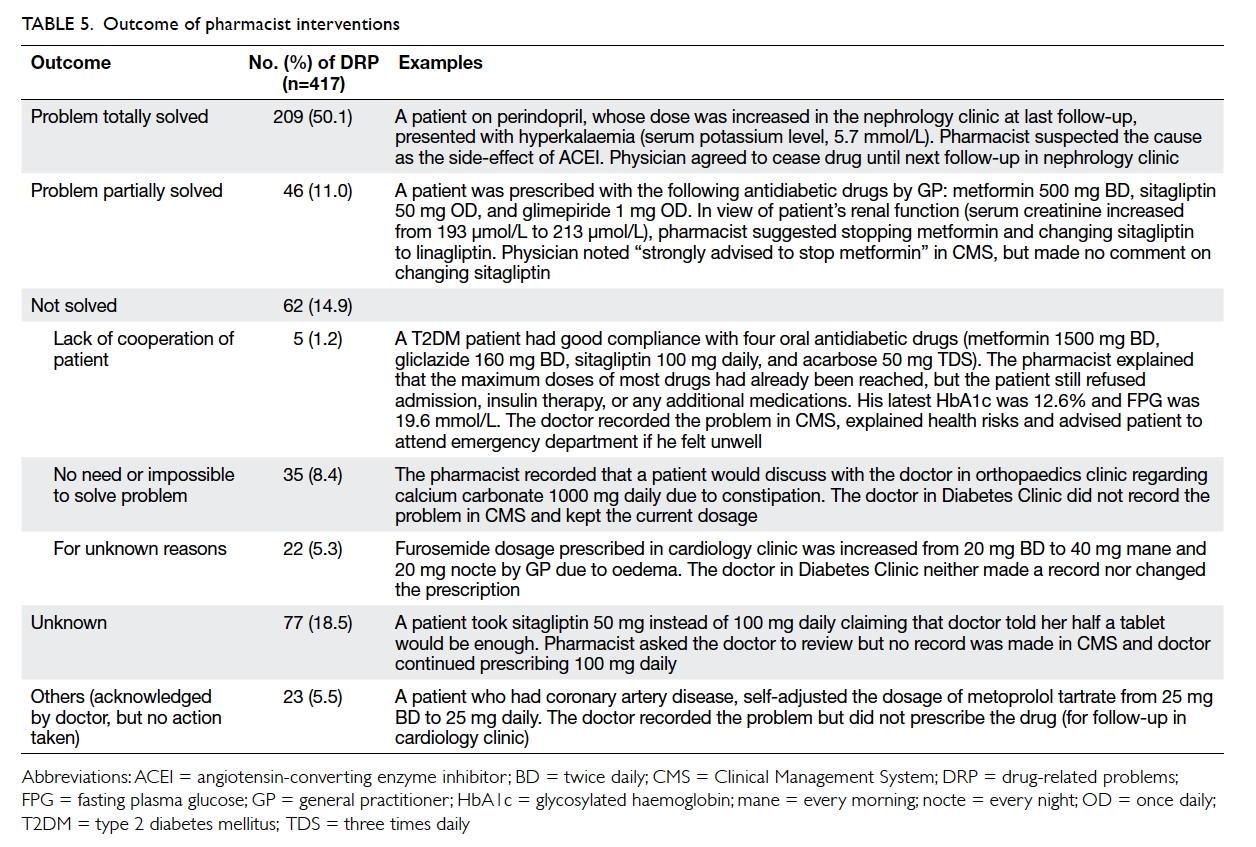

Outcome of pharmacist interventions

As Table 5 shows, modifying drug regimens or

reinforcing compliance by doctors or referral to

pharmacists solved 209 (50.1%) DRPs. On the other

hand, 46 (11.0%) DRPs were partially resolved

by doctors adjusting prescriptions, although not

according to pharmacist recommendations; 62

(14.9%) DRPs were not resolved due to patient

reluctance to change prescriptions, resolution

considered unnecessary, or for unknown reasons;

23 (5.5%) DRPs had an unknown outcome because

these were non-compliance issues not acknowledged

by doctors.

Discussion

The incidence of patients with DRPs (62.8%) and the

mean number of DRPs per patient analysed (0.9) in

this study were comparable to a Norwegian study

(59.2% and 1.2, respectively)10 but considerably

lower than those identified in four overseas studies

(incidence of 80.7%-90.5%, and mean number of

DRPs per patient between 1.9 ± 1.2 and 4.6 ± 1.7).9 11 12 36

Such discrepancies might be attributed to variations

in patient selection criteria, data collection methods,

pharmacists’ clinical experience, as well as study

duration and setting.9 36 37

The majority of DRPs were dosing problems

(43.9%), with “drug dose too low or dosage regimen

insufficient” as the largest subcategory. In contrast

to the lower percentage (5.9%-21.6%) in five overseas

studies,9 10 11 12 36 our high prevalence of dosing problems was in line with a local study of medication incidents

among hospital in-patients,38 mostly arising from

self-adjustment of dosage or frequency, confusion

about previous dose changes and dosage modification

by GPs or doctors overseas. These highlight the

pivotal role of local pharmacists in conducting MR,

reviewing drug dosages to ensure safety and efficacy,

monitoring patients’ metabolic control regularly as

well as reminding patients and/or their caregivers to

maintain an updated medication list and follow the

latest drug label instructions.

Drug choice problem was the second most

common DRP; 17.3% of DRPs related to this category,

which is comparable to the findings of two overseas

studies (9.1%, 23%)9 36 but deviating from others (31.8%-30.2%).10 11 The most common subcategory was “no drug prescribed but clear indication”, such

as the omission of angiotensin-converting enzyme

inhibitor/angiotensin-receptor blocker (ACEI/ARB) in patients with microalbuminuria or patient’s

reluctance to use insulin. Hence, pharmacists have

a role in advising doctors to adhere to the latest

treatment guidelines and educate patients about the

treatment benefits of each drug class.39 Other causes

of problems surrounding drug choice included drug

duplication and changes to drug choices by GPs to

prevent side-effects. This suggests that some DRPs

might have arisen due to the lack of a common

platform between the public and private health care

sector for sharing patient information. Pharmacists

can make a valuable contribution by establishing

a patient’s drug history by MR and by liaison with

different health care sectors.

Adverse reactions were the third most

common DRP (15.6%). The major types of “side-effects suffered (non-allergic)” were insulin-induced

hypoglycaemia, gastrointestinal disturbances, and

dizziness caused by antidiabetic drugs, for which

pharmacists recommended changes in drug choice

or dosage. Adverse reactions could lead to other

DRP categories,7 such as drug choice and drug use

problems. This reflects the pharmacist’s pivotal role

in reviewing prescribed doses, suggesting dosage

adjustments to doctors, monitoring adverse effects,

and providing information about prevention of

side-effects (such as performing SMBG regularly to

prevent hypoglycaemia).39

Drug use issues were the fourth most common

category with comparable prevalence (12.0%) with a

Malaysian study9 although this ranges widely among

other studies (3.8%-54.2%).10 11 36 Reasons for the

subcategory of “drug not taken/administered at all”

included inability to purchase a self-financed item

due to cost, ignorance of the indications, concern

about side-effects, and confusion about previous

regimen changes.40 In our study, pharmacists

mainly intervened by direct patient counselling,

recommending reinforcement of patient compliance

to doctors or suggesting changes to drug regimens.

Pharmacists could also work closely with other

DMT members to educate patients about their

disease and the most updated regimen, address

drug cost concerns or side-effects, and encourage

patients to update their medication list and use dose

administration aids such as pill boxes.41

The low prevalence of drug interactions

(1.0%) was similar to that (0.6%) in a Danish study,36

although much higher percentages were found

in three other studies (8.0%-16.3%),9 10 11 possibly

ascribed to differences in prescribing practice,

references used to define drug interactions,9 and

also because CMS could already detect a range

of clinically significant interactions when doctors

issued prescriptions. Nonetheless system checking

and prompts cannot replace clinical judgement or

recommendations of alternative regimens. Other

categories of DRPs included “insufficient awareness

of health and diseases” (such as poor dietary control)

and “inappropriate timing of administration”, but

this category could also encompass therapy failure

and inappropriate lifestyle choices, resulting in

greater variation of prevalence from overseas studies

(6.8%-46.6%).9 10 11 36 Pharmacists are ideally positioned

to advise patients about the importance of diet,

smoking cessation, regular exercise, and SMBG.22

The drug classes most implicated in DRPs

were for the endocrine system (45.6%) followed by

cardiovascular system (38.1%). These findings were

not surprising as insulins, oral antidiabetic drugs,

antihypertensive, antihyperlipidaemic, antiplatelet

agents, and ACEI/ARB are most commonly

prescribed to manage diabetes, its co-morbidities

and complications.11 39

The majority of DRPs were classified as

moderate. Among similar overseas studies, only

one analysed the clinical significance of DRPs, in

which 87% had high or medium clinical/practical

relevance.10 These findings could not be readily

compared with the present study because of

different assessment scales, potential variations

in reviewers’ clinical experience,35 and unknown

relative proportions of cases with medium and high

relevance.

Over half of the DRPs were totally solved as

doctors implemented pharmacist recommendations.

The acceptance rate was somewhat similar to that

observed in two overseas studies (60.2%-62.7%).12 13 The physicians acknowledged the provision of

service by pharmacists and were more aware of the

written recommendations provided by pharmacists.

In particular, the value of verbal communication

between different health care professionals in

resolving or preventing DRPs has been recognised

in earlier studies,10 42 43 44 45 suggesting potential improvement in the acceptance rate if pharmacists

had more time to hand over DRPs by speaking with

doctors.

The outcome of pharmacist interventions could

also be influenced by doctors’ clinical experience and

familiarity with the new service. Doctors’ acceptance

level could have been underestimated since some

of them might have neglected or missed written

information from pharmacists. This highlights the

importance of promoting the role of pharmacists to

doctors and keeping all participating doctors well-informed.

Difficulties and limitations

This pilot study allowed for an opportunity to assess

the proportion of patients who might be seen by

clinical pharmacists in a busy specialist out-patient

clinic at a teaching hospital. Approximately 10% of

patients were chosen each week and not all eligible

patients could be selected owing to time restrictions.

The number of patients interviewed was further

limited due to time constraints, patient absence or

refusal. Local figures from the QMH Diabetes Clinic

indicate that approximately 7% to 8% of all patients

who attend the clinic are deemed ‘high risk’, based

on ongoing work and prioritisation of those taking

five or more regular medications. Limited work

space was another consideration. A designated area

is required to conduct patient interviews. Further

arrangements could be made with the medical and

nursing staff in the Diabetes Clinic to access better

space.

This study only described the current situation

of DRPs. It did not assess the implementation of

interventions and their impact on patient health

outcome. As the majority of patients did not bring

their drugs to the clinic and had no medication

list available, the MR process was not always

comprehensive or effective. Only a minority of

patients could name their regular drugs. The

majority relied on pharmacist investigation and

prompts about the colour, shape, package, or

indication of each drug. Due to the potential

for misinterpretation, DRP prevalence may be

underestimated. One possible solution might be

to show patients samples of commonly prescribed

medications. Alternatively, selected patients could

be telephoned in advance and asked to bring along

their medications, although this measure may not be

sustainable. A multifaceted promotional campaign

could be introduced to encourage patients to bring

their regular medications to clinic. This has been

shown to be effective in an emergency setting.46

Although completed MR forms were

presented to doctors after the interviews, some

written information might have been missed with

a consequent lack of response to certain DRPs.

Pharmacists should ideally have informed doctors

about every DRP in person, but this was not always

possible due to time constraints and the great

volume of patients. In the long run, pharmacists

should document DRPs and their recommendations

in the CMS. This would enhance visibility and allow

doctors to input their response electronically and

facilitate organised documentation and easy data

retrieval.

Future directions

Upon completion of this study, pharmacists have

been continuing to provide MR and medication

review services in QMH Diabetes Clinic. They have

also been collecting data about DRPs to plan for a

sustainable service. Following a longer study period,

patient and staff satisfaction surveys could be

introduced and also control groups added to enable

comparison of the effectiveness of pharmacist

intervention. This would further support the

extension of hours of service and potentially the

setup of similar pharmacy services to other hospitals

and diabetes clinics in Hong Kong.

Conclusions

Approximately two thirds of patients at the Diabetes

Clinic had at least one DRP. The most frequent

categories of DRPs were related to dosing, drug

choice, and non-allergic adverse reaction. Drugs

targeting the endocrine and cardiovascular systems

were most commonly involved. The majority of DRPs

were of moderate clinical significance. Pharmacist

interventions for over half the DRPs were accepted

or acknowledged by prescribers. Through effective

communication and collaboration within the

multidisciplinary health care team, pharmacists

had a positive impact on identifying, resolving,

and preventing DRPs. Future plans to sustain the

diabetes service will enable more local research to

enhance medication safety and optimise patients’

medication regimens in diabetes management.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Ms Cyan Chan for her

assistance in patient screening and data collection,

and pharmacists Ms Phoebe Chan (HKU); Ms Amy

Chan, Ms Dominique Yeung, Ms Katie Chan, and Mr

Ric Fung (QMH); Prof Karen Lam (QMH); nursing

and medical staff in S6 Diabetes Clinic, QMH for

their advice and contributions to service provision

in the study. We would also like to thank Mr Michael

Ling and Ms Elaine Lo (Kwong Wah Hospital);

Dr Michael Mok (Geelong Hospital, Victoria,

Australia); Dr Vickie Tse (HKU) contributing to the

independent assessment of clinical severity of DRPs;

and Dr Anthony Tam (HKU) and Sharon Law (HKU)

for proofreading the manuscript.

References

1. International Diabetes Federation International diabetes

atlas. 6th ed. Available from: http://www.diabetesatlas.org/resources/previous-editions.html. Accessed Mar 2014.

2. Fowler MJ. Microvascular and macrovascular

complications of diabetes. Clin Diabetes 2008;26:77-82. Crossref

3. Tapp H, Phillips SE, Waxman D, Alexander M, Brown R,

Hall M. Multidisciplinary team approach to improved

chronic care management for diabetic patients in an urban

safety net ambulatory care clinic. J Am Board Fam Med

2012;25:245-6. Crossref

4. Hellström LM, Bondesson Å, Höglund P, Eriksson T. Errors

in medication history at hospital admission: prevalence

and predicting factors. BMC Clin Pharmacol 2012;12:9. Crossref

5. Krska J, Cromarty JA, Arris F, et al. Pharmacist-led

medication review in patients over 65: a randomized,

controlled trial in primary care. Age Ageing 2001;30:205-11. Crossref

6. Draft statement on pharmaceutical care. ASHP Council

on Professional affairs. American Society of Hospital

Pharmacists. Am J Hosp Pharm 1993;50:126-8.

7. Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe. The PCNE

Classification V 5.01. 2006. Available from: http://www.pcne.org/upload/files/16_PCNE_classification_V5.01.pdf.

Accessed 22 Oct 2013.

8. Viktil KK, Blix HS, Moger TA, Reikvam A. Polypharmacy

as commonly defined is an indicator of limited value in the

assessment of drug-related problems. Br J Clin Pharmacol

2007;63:187-95. Crossref

9. Zaman Huri H, Fun Wee H. Drug related problems in type

2 diabetes patients with hypertension: a cross-sectional

retrospective study. BMC Endocr Disord 2013;13:2. Crossref

10. Granas AG, Berg C, Hjellvik V, et al. Evaluating

categorisation and clinical relevance of drug-related

problems in medication reviews. Pharm World Sci

2010;32:394-403. Crossref

11. van Roozendaal BW, Krass I. Development of an evidence-based

checklist for the detection of drug related problems

in type 2 diabetes. Pharm World Sci 2009;31:580-95. Crossref

12. Borges AP, Guidoni CM, Ferreira LD, de Freitas O, Pereira

LR. The pharmaceutical care of patients with type 2

diabetes mellitus. Pharm World Sci 2010;32:730-6. Crossref

13. DeName B, Divine H, Nicholas A, Steinke DT, Johnson CL.

Identification of medication-related problems and health

care provider acceptance of pharmacist recommendations

in the DiabetesCARE program. J Am Pharm Assoc

2008;48:731-6. Crossref

14. Kiel PJ, McCord AD. Pharmacist impact on clinical

outcomes in a diabetes disease management program via

collaborative practice. Ann Pharmacother 2005;39:1828-32. Crossref

15. Wubben DP, Vivian EM. Effects of pharmacist outpatient

interventions on adults with diabetes mellitus: a systematic

review. Pharmacotherapy 2008;28:421-36. Crossref

16. Evans CD, Watson E, Eurich DT, et al. Diabetes and

cardiovascular disease interventions by community

pharmacists: a systematic review. Ann Pharmacother

2011;45:615-28. Crossref

17. Chan CW, Siu SC, Wong CK, Lee VW. A pharmacist care

program: positive impact on cardiac risk in patients with

type 2 diabetes. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 2012;17:57-64. Crossref

18. Pepper MJ, Mallory N, Coker TN, Chaki A, Sando KR.

Pharmacists’ impact on improving outcomes in patients

with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Educ 2012;38:409-16. Crossref

19. Jarab AS, Alqudah SG, Mukattash TL, Shattat G, Al-Qirim T. Randomized controlled trial of clinical pharmacy

management of patients with type 2 diabetes in an

outpatient diabetes clinic in Jordan. J Manag Care Pharm

2012;18:516-26. Crossref

20. Jacobs M, Sherry PS, Taylor LM, Amato M, Tataronis GR,

Cushing G. Pharmacist Assisted Medication Program

Enhancing the Regulation of Diabetes (PAMPERED) study.

J Am Pharm Assoc 2012;52:613-21. Crossref

21. Ali M, Schifano F, Robinson P, et al. Impact of community

pharmacy diabetes monitoring and education programme

on diabetes management: a randomized controlled study.

Diabet Med 2012;29:e326-33. Crossref

22. Al Mazroui NR, Kamal MM, Ghabash NM, Yacout TA,

Kole PL, McElnay JC. Influence of pharmaceutical care on

health outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Br J Clin Pharmacol 2009;67:547-57. Crossref

23. Mehuys E, Van Bortel L, De Bolle L, et al. Effectiveness

of a community pharmacist intervention in diabetes

care: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Pharm Ther

2011;36:602-13. Crossref

24. Shah M, Norwood CA, Farias S, Ibrahim S, Chong PH,

Fogelfeld L. Diabetes transitional care from inpatient to

outpatient setting: pharmacist discharge counseling. J

Pharm Pract 2013;26:120-4. Crossref

25. Heisler M, Hofer TP, Schmittdiel JA, et al. Improving

blood pressure control through a clinical pharmacist

outreach program in patients with diabetes mellitus

in 2 high-performing health systems: the adherence

and intensification of medications cluster randomized,

controlled pragmatic trial. Circulation 2012;125:2863-72. Crossref

26. Dobesh PP. Managing hypertension in patients with type 2

diabetes mellitus. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2006;63:1140-9. Crossref

27. Planas LG, Crosby KM, Mitchell KD, Farmer KC. Evaluation

of a hypertension medication therapy management

program in patients with diabetes. J Am Pharm Assoc

2009;49:164-70. Crossref

28. Leal S, Soto M. Chronic kidney disease risk reduction in

a Hispanic population through pharmacist-based disease-state

management. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2008;15:162-7. Crossref

29. Leung WY, So WY, Tong PC, Chan NN, Chan JC. Effects

of structured care by a pharmacist-diabetes specialist team

in patients with type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Am J Med

2005;118:1414. Crossref

30. American Pharmacists Association. DOTx. MED:

Pharmacist-delivered interventions to improve care for

patients with diabetes. J Am Pharm Assoc 2012;52:25-33. Crossref

31. Björkman IK, Sanner MA, Bernsten CB. Comparing 4

classification systems for drug-related problems: processes

and functions. Res Social Adm Pharm 2008;4:320-31. Crossref

32. Eichenberger PM, Lampert ML, Kahmann IV, van

Mil JW, Hersberger KE. Classification of drug-related

problems with new prescriptions using a modified PCNE

classification system. Pharm World Sci 2010;32:362-72. Crossref

33. Hohmann C, Eickhoff C, Klotz JM, Schulz M, Radziwill

R. Development of a classification system for drug-related

problems in the hospital setting (APS-Doc) and assessment

of the inter-rater reliability. J Clin Pharm Ther 2012;37:276-81. Crossref

34. British Medical Association, Royal Pharmaceutical Society

of Great Britain. British National Formulary 71. London:

British Medical Association, Royal Pharmaceutical Society;

2016.

35. Dean BS, Barber ND. A validated, reliable method of

scoring the severity of medication errors. Am J Health Syst

Pharm 1999;56:57-62.

36. Haugbølle LS, Sørensen EW. Drug-related problems

in patients with angina pectoris, type 2 diabetes and

asthma—interviewing patients at home. Pharm World Sci

2006;28:239-47. Crossref

37. Westerlund T, Almarsdottir AB, Melander A. Factors

influencing the detection rate of drug-related problems in

community pharmacy. Pharm World Sci 1999;21:245-50. Crossref

38. Song L, Chui WC, Lau CP, Cheung BM. A 3-year study of

medication incidents in an acute general hospital. J Clin

Pharm Ther 2008;33:109-14. Crossref

39. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care

in diabetes—2013. Diabetes Care 2013;36 Suppl 1:S11-66. Crossref

40. Odegard PS, Gray SL. Barriers to medication adherence

in poorly controlled diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Educ

2008;34:692-7. Crossref

41. Morello CM, Chynoweth M, Kim H, Singh RF, Hirsch JD.

Strategies to improve medication adherence reported by

diabetes patients and caregivers: results of a taking control

of your diabetes survey. Ann Pharmacother 2011;45:145-53. Crossref

42. Perera PN, Guy MC, Sweaney AM, Boesen KP. Evaluation

of prescriber responses to pharmacist recommendations

communicated by fax in a medication therapy management

program (MTMP). J Manag Care Pharm 2011;17:345-54. Crossref

43. Doucette WR, McDonough RP, Klepser D, McCarthy

R. Comprehensive medication therapy management:

identifying and resolving drug-related issues in a

community pharmacy. Clin Ther 2005;27:1104-11. Crossref

44. Chrischilles EA, Carter BL, Lund BC, et al. Evaluation

of the Iowa Medicaid pharmaceutical case management

program. J Am Pharm Assoc 2004;44:337-49. Crossref

45. Galt KA. Cost avoidance, acceptance, and outcomes

associated with a pharmacotherapy consult clinic in

a Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Pharmacotherapy

1998;18:1103-11.

46. Chan EW, Taylor SE, Marriott JL, Barger B. Bringing

patients’ own medications into an emergency department

by ambulance: effect on prescribing accuracy when these

patients are admitted to hospital. Med J Aust 2009;191:374-7.