Hong Kong Med J 2017 Jun;23(3):222–30 | Epub 5 May 2017

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj166023

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

A descriptive study of Lewy body dementia

with functional imaging support in a Chinese

population: a preliminary study

YF Shea, MRCP(UK), FHKAM (Medicine);

LW Chu, MD, FRCP;

SC Lee, BHS(Nursing)

Geriatrics Division, Department of Medicine, Queen Mary Hospital,

Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr YF Shea (elphashea@gmail.com)

Abstract

Introduction: Lewy body dementia includes

dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease

dementia. There have been limited clinical studies

among Chinese patients with Lewy body dementia.

This study aimed to review the presenting clinical

features and identify risk factors for complications

including falls, dysphagia, aspiration pneumonia,

pressure sores, and mortality in Chinese patients

with Lewy body dementia. We also wished to

identify any difference in clinical features of patients

with Lewy body dementia with and without an

Alzheimer’s disease pattern of functional imaging.

Methods: We retrospectively reviewed 23 patients

with Lewy body dementia supported by functional

imaging. Baseline demographics, presenting clinical

and behavioural and psychological symptoms of

dementia, functional and cognitive assessment

scores, and complications during follow-up were

reviewed. Patients with Lewy body dementia were

further classified as having an Alzheimer’s disease

imaging pattern if functional imaging demonstrated

bilateral temporoparietal hypometabolism or

hypoperfusion with or without precuneus and

posterior cingulate gyrus hypometabolism or

hypoperfusion.

Results: The pre-imaging accuracy of clinical

diagnosis was 52%. In 83% of patients, behavioural

and psychological symptoms of dementia were

evident. Falls, dysphagia, aspiration pneumonia,

pressure sores, and death occurred in 70%, 52%,

26%, 26%, and 30% of patients, respectively with

corresponding event rates per person-years of 0.32,

0.17, 0.18, 0.08, and 0.10. Patients with aspiration

pneumonia compared with those without were more

likely to have dysphagia (100% vs 35%; P=0.01).

Deceased patients with Lewy body dementia,

compared with alive patients, had a higher (median

[interquartile range]) presenting Clinical Dementia

Rating score (1 [1-2] vs 0.5 [0.5-1.0]; P=0.01), lower

mean (± standard deviation) baseline Barthel index

(13 ± 7 vs 18 ± 4; P=0.04), and were more likely to be

prescribed levodopa (86% vs 31%; P=0.03). Patients

with Lewy body dementia with an Alzheimer’s

disease pattern of functional imaging, compared

with those without the pattern, were younger at

presentation (mean ± standard deviation, 73 ± 6 vs

80 ± 6 years; P=0.02) and had a lower Mini-Mental State

Examination score at 1 year (15 ± 8 vs 22 ± 6; P=0.05).

Conclusions: Falls, dysphagia, aspiration pneumonia,

and pressure sores were common among patients

with Lewy body dementia. Those with an Alzheimer’s

disease pattern of functional imaging had a younger

age of onset and lower 1-year Mini-Mental State

Examination score.

New knowledge added by this study

- Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia were present in 83% of patients with Lewy body dementia (LBD).

- Falls, dysphagia, aspiration pneumonia, and pressure sores were common complications in LBD patients.

- Chinese LBD patients with an Alzheimer’s disease pattern of functional imaging had a younger age of onset and lower 1-year Mini-Mental State Examination score.

- Such information is useful in the formulation of a management plan, including advance care planning, for Chinese LBD patients.

Introduction

Lewy body dementia (LBD) includes dementia with

Lewy bodies (DLB) and Parkinson’s disease dementia

(PDD).1 Pathological hallmarks of LBD include α-synuclein neuronal inclusions (Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites) with subsequent neuronal loss.1

The difference between DLB and PDD lies in the

sequence of onset of dementia and parkinsonism,

although syndromes and pathological changes

become similar with progression.1 2 Thus, they are regarded as a continuum instead of two separate

entities. In western studies, approximately 10% to

15% of patients with dementia had DLB.1 In contrast,

only 3% of 1532 patients with dementia followed up

at the memory clinic of Queen Mary Hospital in

Hong Kong had LBD (unpublished data). It is likely

that LBD remains under-recognised among the

Chinese population.

Compared with autopsy, sensitivity and

specificity for clinical diagnosis of DLB have been

reported to be 32% and 95%, respectively.1 In our

memory clinic, 50% of DLB patients were initially

misdiagnosed (mostly as Alzheimer’s disease [AD]

in 75% of cases).3 There has been only one case series

of 35 Chinese DLB patients and diagnosis was based

mainly on clinical criteria.4 The presence of occipital

hypometabolism on [18F]-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose

positron emission tomography (18FDG-PET)

has a sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 71% to 80% in

differentiating AD and DLB patients.5

Pathologies of AD are common in DLB

patients; 35% of patients with Parkinson’s disease

fulfil the pathological diagnostic criteria of AD,

while deposition of amyloid plaques is present in

approximately 85% of DLB patients.6 A meta-analysis

revealed a positive amyloid scan in 57% and 35% of

patients with DLB and PDD, respectively.5 A higher

cortical amyloid burden has been associated with

greater cortical and medial temporal lobe atrophy in

LBD patients.6 Significant cortical amyloid burden

may accelerate the cognitive decline in LBD patients,

suggesting the possibility of a synergistic contribution

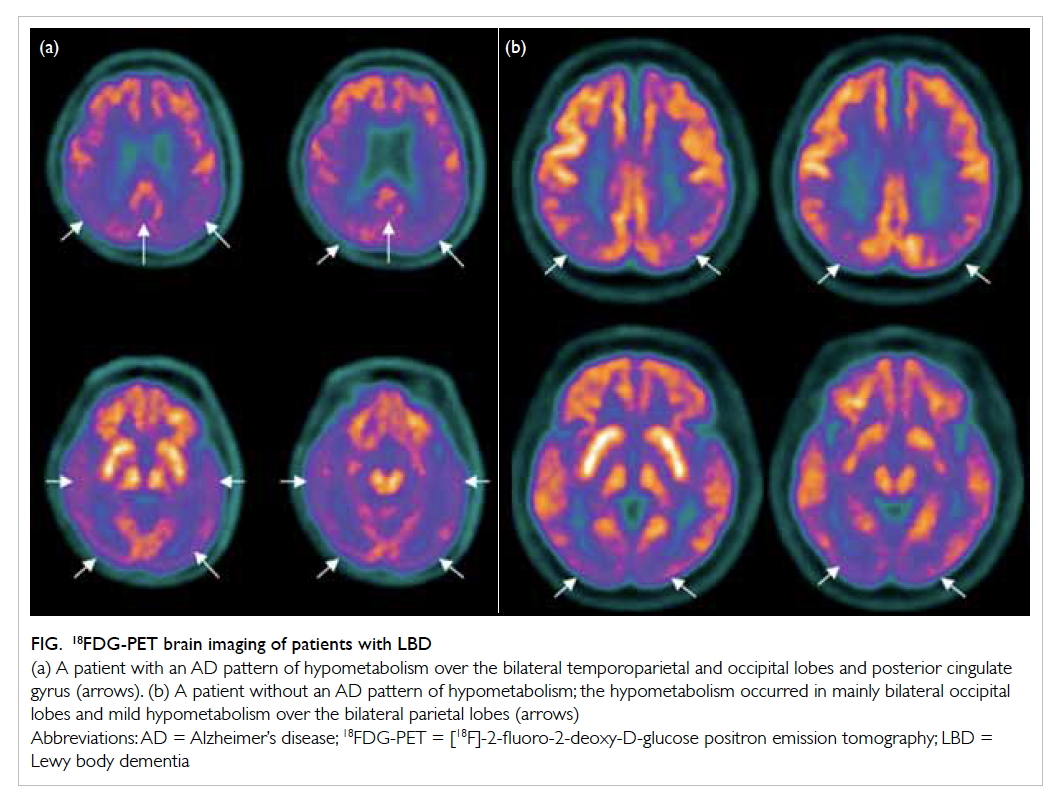

of AD pathologies to LBD dementia.6 On 18FDG-PET,

apart from bilateral occipital hypometabolism,

some LBD patients also demonstrate an AD pattern

of hypometabolism, ie temporoparietal, posterior

cingulate gyrus or precuneus hypometabolism

(Fig).7 In a recent study comparing 12 patients

with DLB and an AD pattern of hypometabolism

on 18FDG-PET with 11 patients with DLB and no

AD pattern of hypometabolism, the former had

a higher prevalence of visual hallucinations and

extracampine hallucination.7 As far as we are aware,

an AD pattern of functional imaging has not been

studied in Chinese patients with DLB.

In contrast with AD, the clinical features of

patients with DLB are unfamiliar to the general

public. In a recent study that involved 125 carers of

LBD patients, 82% to 96% expressed a wish to have

information and support about visual hallucinations,

changes in the brain and the body, and ways to cope

with behavioural changes.8 Unfortunately clinical

studies of LBD among the Chinese population

are limited and none has examined the long-term

outcomes of LBD, including falls, dysphagia,

aspiration pneumonia, pressure sores, mortality,

and behavioural and psychological symptoms of

dementia (BPSD).

Based on a review of the clinical records of

all LBD patients followed up in our memory clinic,

the current study aimed to review the presenting

clinical features and identify risk factors for long-term

outcomes including falls, dysphagia, aspiration

pneumonia, pressure sores, and mortality in Chinese

patients with LBD. It was hoped that this would

provide useful clinical information for carers of such

patients. We also wished to identify any difference in

clinical features of LBD patients with and without an

AD pattern of functional imaging. We hypothesised

that LBD patients with an AD pattern of functional

imaging would have a young age at presentation or

diagnosis due to concomitant AD pathologies.

Methods

This was a retrospective case series of Chinese LBD

patients. The case records of Chinese patients with

LBD who attended a memory clinic at Queen Mary

Hospital between 1 January 2007 and 31 December

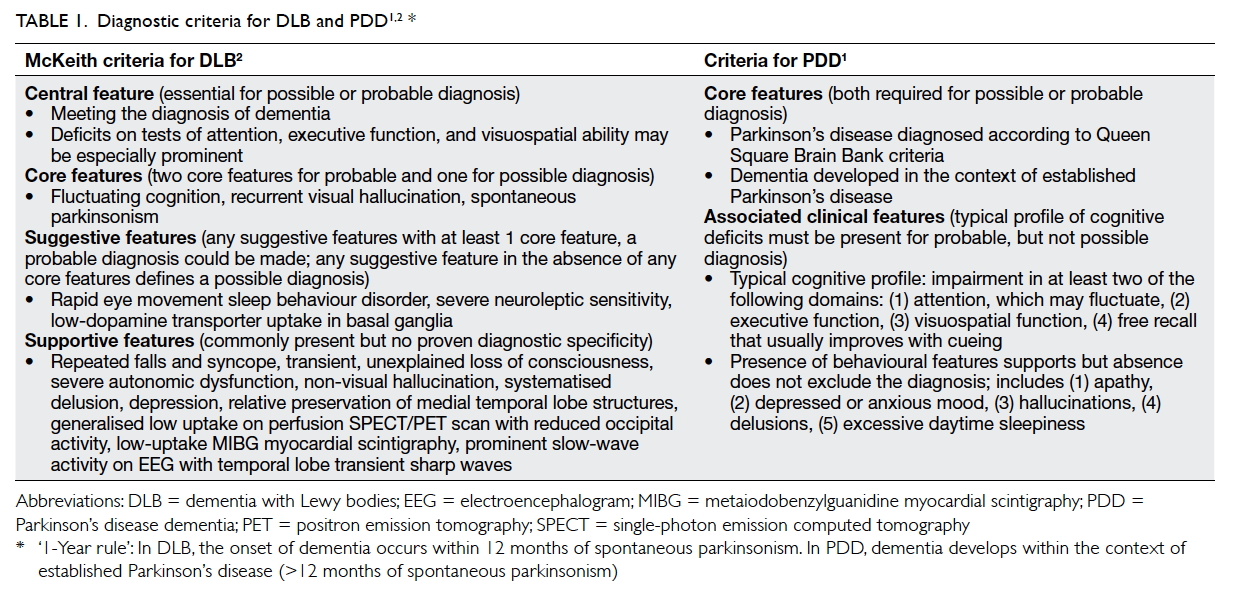

2015 were reviewed. This study was done in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Probable DLB was diagnosed according to McKeith criteria2 (Table 11 2). Probable PDD was diagnosed according to the following:

the patient should meet the diagnostic criteria of

Queen Square Brain Bank criteria with dementia

developing in the context of established Parkinson’s

disease with cognitive impairment in more than one

domain and severe enough to impair daily life (Table 11 2). The differentiation between DLB and PDD

was based on temporal sequence of symptoms—for

DLB, dementia developed before or within 1 year of

parkinsonism (ie the clinical syndrome characterised

by tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity, and postural

instability); for PDD, dementia developed more than

1 year after the established diagnosis of Parkinson’s

disease.1 All patients underwent functional imaging

in the form of 18FDG-PET or technetium-99m

hexamethylpropylene amine oxime single-photon

emission computed tomography (SPECT) that would

show either hypometabolism or hypoperfusion of

the occipital lobes, respectively. Data on baseline

demographics, baseline and first-year Mini-Mental

State Examination (MMSE) score,9 Clinical Dementia

Rating (CDR) score,10 age-adjusted Charlson

Comorbidity Index,11 baseline Neuropsychiatric

Inventory (NPI) score,12 baseline Barthel index–20,13 presenting cognitive symptoms, and BPSD were

derived from clinical records. ‘Time to diagnosis’

was defined as the difference between the date of

first presentation to the memory clinic and the date

of first diagnosis of LBD. Patients with DLB were

further classified as having an ‘AD imaging pattern’

if the functional imaging demonstrated bilateral

temporoparietal hypometabolism or hypoperfusion

with or without precuneus and posterior cingulate

gyrus hypometabolism or hypoperfusion (Fig).7 14

Figure. 18FDG-PET brain imaging of patients with LBD

(a) A patient with an AD pattern of hypometabolism over the bilateral temporoparietal and occipital lobes and posterior cingulate gyrus (arrows). (b) A patient without an AD pattern of hypometabolism; the hypometabolism occurred in mainly bilateral occipital lobes and mild hypometabolism over the bilateral parietal lobes (arrows)

Clinical outcomes including falls, dysphagia,

aspiration pneumonia, development of pressure

sores, and mortality were traced. For patients

with a history of falls, geriatric day hospital (GDH)

training was traced including the pre-/post-training

Elderly Mobility Scale15 and Berg Balance Scale.16 Parkinsonism medication was often titrated at the

GDH. Dysphagia was further subclassified as oral

or pharyngeal according to the clinical

assessment by a speech therapist (ST) or, if available,

a video fluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS).17

Penetration was defined as barium material entering

the airway but not passing below the vocal cords;

aspiration was defined as barium material passing

below the level of the vocal cords.18 The locations

of pressure sores and staging, according to National

Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel,19 were recorded.

‘Time to event’ was defined as the difference between

the date of diagnosis and first appearance of these

events.

Statistical analyses

Parametric variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and non-parametric variables were expressed by median (interquartile range

[IQR]). Descriptive statistics were used to express the

frequency of defining features of LBD. Chi squared

test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare

categorical variables. Independent-samples t test

or Mann-Whitney U test were used to compare

continuous variables when appropriate. Statistical

significance was inferred by a two-tailed P value

of <0.05. All statistical analyses were carried out

using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

(Windows version 18.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], United States).

Results

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics

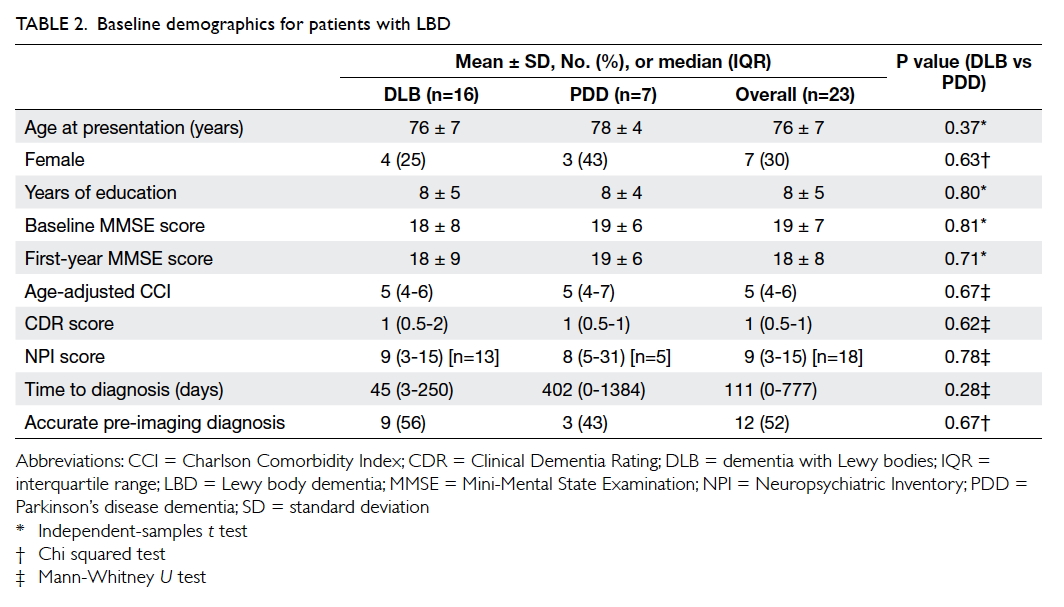

There were 23 patients with LBD (16 with DLB and

7 with PDD). The mean age at presentation was 76 ±

7 years and the mean MMSE score at presentation

was 19 ± 7 with a total duration of follow-up

of 72 patient-years (mean follow-up, 1138 ± 698

days). The baseline demographics of the patients are

summarised in Table 2. There was no statistically significant difference in baseline demographics

between DLB and PDD patients. The time to diagnosis

appeared to be longer but not statistically significant

for PDD patients, possibly due to very small

numbers in the two groups. The overall accuracy of

diagnosis was 52%. Six (38%) of the 16 DLB patients

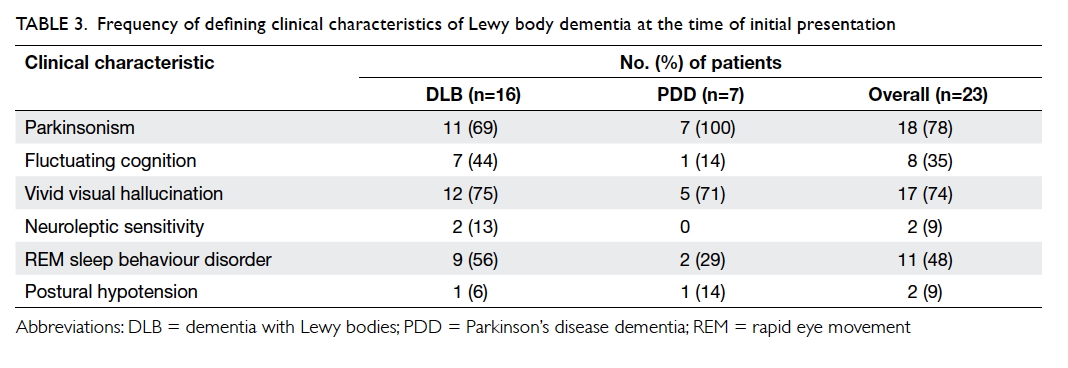

were initially misdiagnosed as AD. The frequency of

defining clinical characteristics of LBD among DLB

and PDD patients is summarised in Table 3. There were no statistically significant differences (results

not shown). Of note, 69% of DLB patients presented

with parkinsonism and 74% of LBD patients had

vivid visual hallucinations. Information about the

content of visual hallucinations was available for

14 of 17 patients: 50% (n=7) involved persons, 7%

(n=1) involved objects, 21% (n=3) a combination

of persons and animals, 7% (n=1) a combination

of insects and animal, 7% (n=1) a combination of

insects and objects, and 7% (n=1) a combination of

animal and objects. An NPI score was available for

78% (18/23) at baseline, of whom 83% (15/18) had

a score of ≥1, and 78% (14/18) had at least one NPI

subcategory rated as severe, ie ≥4. The three most

common BPSD as indicated by a NPI score of ≥1

were visual hallucination (56%), anxiety (50%), and

apathy (50%). There was no significant difference

in BPSD in terms of NPI score for DLB and PDD

patients (results not shown).

Table 3. Frequency of defining clinical characteristics of Lewy body dementia at the time of initial presentation

Falls

Of the patients, 16 (70%) had a total of 23 falls

(all non-syncopal) with four complicated by bone

fractures and two associated with intracerebral

haemorrhage. The event rate was 0.32 per person-years.

Ten patients underwent GDH training after

their fall(s). The median time to first GDH training

(from the time of diagnosis) was 56 (IQR, 56-663)

days with a mean time of 93 ± 44 days. Paired-samples

t test did not identify any significant pre-/post-training

difference in Elderly Mobility Scale15 or Berg

Balance Scale16 scores (10 ± 4 vs 11 ± 5, P=0.81 and

25 ± 13 vs 25 ± 14, P=1.0, respectively). Comparison

of LBD patients with and without a fall history

revealed no significant difference in clinical features

(including visual hallucination, parkinsonism,

and fluctuation of consciousness) or medication

(including benzodiazepine or antipsychotics)

[results not shown]. Parkinsonism was numerically

more prevalent among fallers (88% vs 57%; P=0.14).

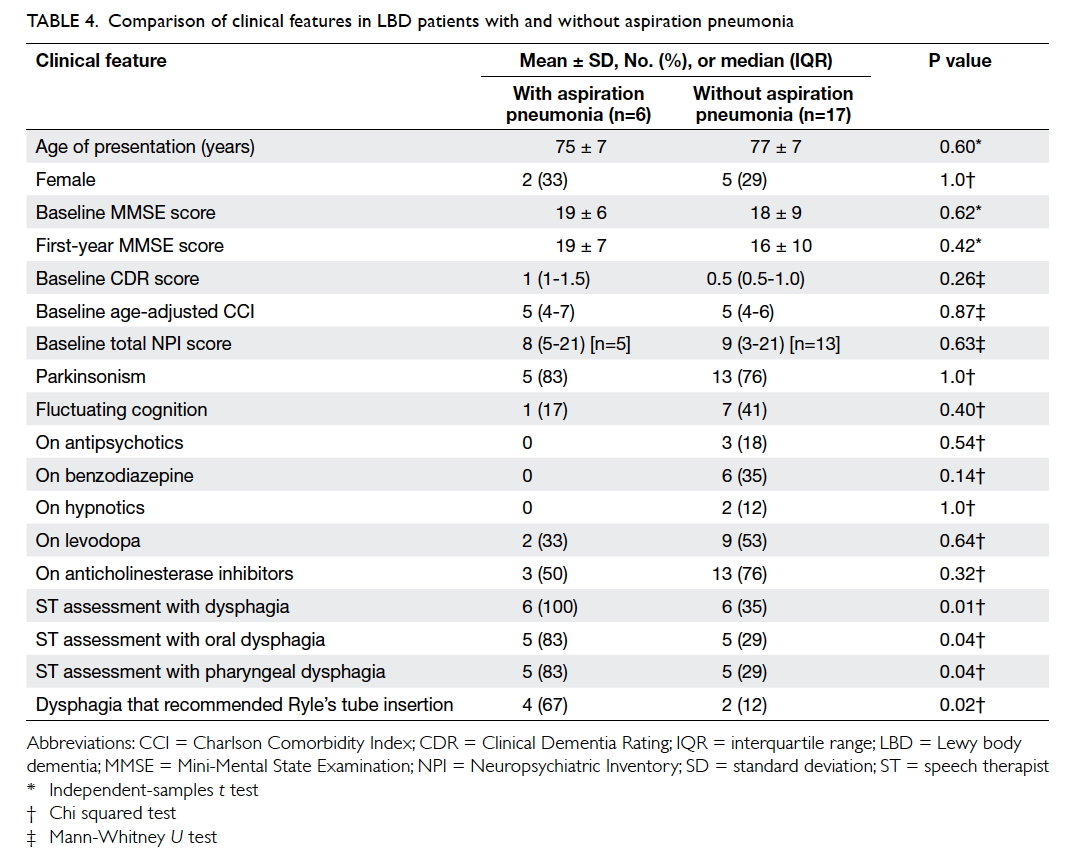

Dysphagia and aspiration pneumonia

Of the patients, six (26%) had a total of 13 episodes

of pneumonia, and 12 (52%) had dysphagia. The

mean time to first episode of aspiration pneumonia

was 866 ± 689 days (median, 634; IQR, 315-1456

days; n=6) and to first diagnosis of dysphagia 951 ± 734 days (median, 862; IQR, 311-1624 days; n=12).

Five patients underwent VFSS (time to VFSS: 831

± 728; median, 723; IQR, 154-1562 days). Three of

four patients with penetration developed aspiration

pneumonia; both patients with aspiration on VFSS

developed aspiration pneumonia. The event rates

were 0.17 and 0.18 per person-years for dysphagia

and aspiration pneumonia, respectively. Patients

with LBD with a history of aspiration pneumonia

compared with those without were more likely to

have been identified by the ST to have

dysphagia (100% vs 35%; P=0.01), oral dysphagia

(83% vs 29%; P=0.04), pharyngeal dysphagia (83% vs

29%; P=0.04), or dysphagia that required Ryle’s tube

insertion (67% vs 12%; P=0.02) [Table 4].

Pressure sores

Six (26%) patients developed pressure sores with four

over the sacrum and two over the heel (two in stage

1, two in stage 3, and two in stage 4). The mean time

to development of pressure sore was 978 ± 599 days

(median, 994; IQR, 379-1528 days). The event rate

was 0.08 per person-years. A comparison between

LBD patients with or without pressure sores did not

identify any significant difference in clinical features

(results not shown).

Mortality

Seven (30%) patients died of various diseases: three

(43%) of pneumonia, two (29%) of unexplained

cardiac arrest (UCA), and one (14%) each of pressure

sore sepsis and choking. The mean time to death was

894 ± 617 days (median, 798; IQR, 312-1597 days).

The event rate was 0.10 per person-years. Deceased

patients with LBD, compared with alive patients,

scored a higher presenting CDR (median [IQR]: 1

[1-2] vs 0.5 [0.5-1.0]; P=0.01), lower mean baseline

Barthel index (13 ± 7 vs 18 ± 4; P=0.04), and were

more likely to have been prescribed levodopa (86%

vs 31%; P=0.03).

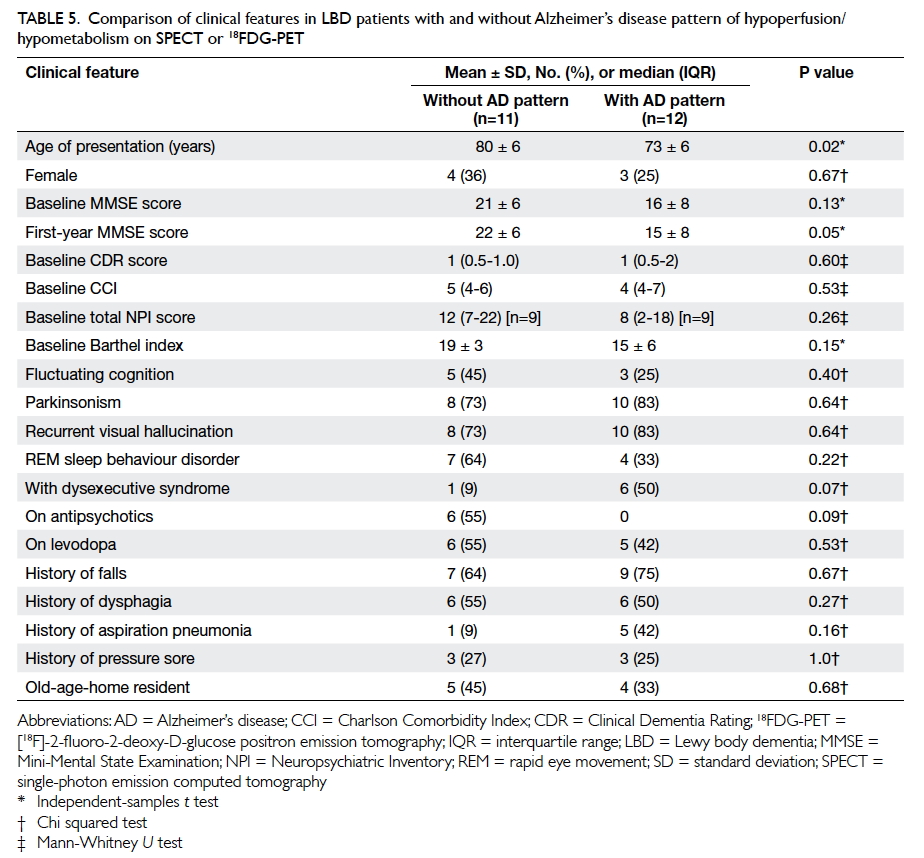

Alzheimer’s disease pattern of functional imaging

Of the patients, 19 underwent 18FDG-PET and

four underwent perfusion SPECT imaging.

Twelve patients (9 DLB and 3 PDD) had

an AD pattern of functional imaging: all 12 had

bilateral temporoparietal lobe hypometabolism/hypoperfusion; three patients concomitantly had

hypoperfusion/hypometabolism over the posterior

cingulate gyrus and one patient had additional

hypometabolism over the precuneus. Patients with

LBD with an AD pattern of functional imaging

compared with those without were younger at

presentation (73 ± 6 vs 80 ± 6 years; P=0.02) and

had a lower MMSE score at 1 year (15 ± 8 vs 22 ± 6;

P=0.05). There was no difference in the presentation

of visual hallucination between the two groups of

patients (Table 5).

Table 5. Comparison of clinical features in LBD patients with and without Alzheimer’s disease pattern of hypoperfusion/hypometabolism on SPECT or 18FDG-PET

Discussion

An accurate diagnosis of LBD is important. It allows

prescription of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors or

avoidance of antipsychotics in view of the risk of

neuroleptic sensitivity. An overall accuracy of clinical

diagnosis of 52% in our study is similar to findings

in western studies, eg 62% by a neurologist.20 Our

results reveal that no single diagnostic criteria or

test is infallible and the diagnosis needs follow-up

review and support from functional imaging when

appropriate. In our series, 38% of DLB patients

were initially misdiagnosed as AD. This is thought

to have been related to the presence of amnesia in

all patients at initial presentation: only 69% of DLB

patients presented with parkinsonism. There was no

difference in the clinical features of DLB and PDD

patients. Braak et al21 have proposed a pathological

staging of Parkinson’s disease with Lewy body

pathology starting in the dorsal IX/X motor nucleus

or adjoining intermediate reticular zone, and

spreading rostrally in the brainstem then to the

limbic system and subsequently to the neocortex

with the underlying mechanism being the spread

of α-synuclein from cell to cell. This might explain

why DLB and PDD can progress and later overlap

clinically.

Compared with the previous literature review

of Chinese LBD case reports (1980-2012) by Han et al4 including 31 DLB and four PDD patients with a younger mean age of onset (67 ± 10 years), more

patients in our series presented with cognitive

decline (100% vs 60%), parkinsonism (78% vs 9%),

visual hallucinations (74% vs 9%), and rapid eye movement

sleep behaviour disorder (48% vs 11%).

These differences may be related to the heightened

awareness of the core features of LBD among

Chinese doctors in recent years or because patients

in our series presented at a more advanced stage of

dementia (Han et al4 did not state the severity of

dementia). Nonetheless, both case series reported

similar rates of postural hypotension (9% vs 3%) and

BPSD (83% vs 86%).4 The rate of postural hypotension

in both case series is much lower than that reported

in other literature on DLB patients, ie 50%.22 The

lower rates of postural hypotension may be related to

under-recognition. Similar to our findings, in a study

of 22 Chinese DLB patients (mean age, 74 ± 8 years;

mean MMSE score, 16 ± 7; mean NPI score, 24 ± 16),

three most commonly observed BPSDs were visual

hallucinations (86%), delusions (64%), and anxiety

(59%); total NPI score was an independent predictor

of caregiver burden (odds ratio=1.537; P=0.048).22

Clinicians should pay particular attention to BPSD,

particularly visual hallucinations and anxiety

symptoms, when managing Chinese LBD patients.

In addition, falls, dysphagia, and pressure

sores can contribute to carer stress but they were

not included in previous studies of LBD patients.23 24 Nearly 70% of our LBD patients experienced falls.

This rate is greater than the previously reported

rates of 11% to 44%.25 26 Although visuospatial impairment, cognitive fluctuation, parkinsonism,

or visual hallucinations were proposed as

possible mechanisms that contributed to falls, only

parkinsonism was identified in one study of 51 AD

and 27 DLB patients as an independent risk factor.25 26 Because of the limited sample size, no significant risk

factors could be identified in our series. With regard

to the finding of limited improvement in mobility

after GDH training, it is likely that many factors affect

the mobility of LBD patients. These factors include

dementia, postural hypotension, and poor balance

from disease. Clinicians should alert carers of the risk of falls and offer advice about general measures for

falls prevention, including addressing environmental

risk factors and use of safety alarms. Compared with

Londos et al’s finding17 that 29% of 82 LBD patients

(median age, 77 years; median MMSE score, 20) had

dysphagia on VFSS, we reported a higher

rate of 52%. When identified by STs,

LBD patients and their carers should be given

advice about diet modification (eg use of thickeners)

and postural changes (eg chin tuck). In addition,

clinicians should titrate the levodopa dose as far as

possible.27

Given that LBD is an irreversible

neurodegenerative disease, advance care planning

(ACP) forms a major part of care.28 Our data for

dysphagia, aspiration pneumonia, pressure sores,

and mortality can offer useful information during

ACP for Chinese LBD patients. Since those patients

who have died had a higher presenting CDR score,

lower Barthel Index, and greater usage of levodopa

(which probably reflects more severe parkinsonism),

ACP should be initiated earlier in LBD patients

with these features. It has been reported that LBD

patients can have UCA and in our series two (28.6%)

patients died of UCA. Unexplained cardiac arrest is

proposed to be related to pathological involvement

of the intermediolateral columns of the spinal

cord, autonomic ganglia, and sympathetic neurons,

affecting either respiration or heart rhythm.29 Such

risk of UCA should be explained during ACP.

Presence of hypometabolism/hypoperfusion over

the temporoparietal lobes/precuneus/posterior

cingulate gyrus was used as surrogate markers of

concomitant AD pathologies in our LBD patients. As

far as we are aware, this is the first study to show that

concomitant AD pathologies among Chinese LBD

patients can result in an early age of presentation

or diagnosis and lower MMSE score at 1 year. Our

findings provide further evidence of the synergistic

contribution of AD pathologies to LBD dementia.6

This study has several limitations. It was a

single-centre retrospective case series, therefore, we

considered clinical features only as present or absent

when clearly stated as such. This might have affected

our results. Pathological diagnosis was not obtained

including pathological proof of concomitant AD

pathologies. Since all subjects were recruited from

the memory clinic, LBD patients who present to a

psychiatric clinic may be different, eg with more

BPSD or visual hallucinations. The severity of

parkinsonism was not graded so the influence of

parkinsonism on long-term outcomes such as falls

or aspiration pneumonia was not fully analysed.

Although our case series comprised the largest

number of Chinese patients with LBD supported by

functional imaging, the number remained limited.

Our findings should be confirmed by a larger study

with Pittsburgh compound B imaging to delineate

the concomitant presence of amyloid plaques.

Conclusions

Falls, dysphagia, aspiration pneumonia, and pressure

sores were common among LBD patients. Lewy body dementia

patients with an AD pattern of neuroimaging had

an earlier age of diagnosis or presentation and lower

1-year MMSE scores. Such information is useful in

the formulation of a management plan for Chinese

LBD patients.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Walker Z, Possin KL, Boeve BF, Aarsland D. Lewy body

dementias. Lancet 2015;386:1683-97. Crossref

2. McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, et al. Diagnosis and

management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report

of the DLB consortium. Neurology 2005;65:1863-72. Crossref

3. Shea YF, Ha J, Lee SC, Chu LW. Impact of 18FDG PET

and 11C-PIB PET brain imaging on the diagnosis of

Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in a regional

memory clinic in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J

2016;22:327-33.

4. Han D, Wang Q, Gao Z, Chen T, Wang Z. Clinical features

of dementia with lewy bodies in 35 Chinese patients.

Transl Neurodegener 2014;3:1. Crossref

5. Valkanova V, Ebmeier KP. Neuroimaging in dementia.

Maturitas 2014;79:202-8. Crossref

6. Gomperts SN. Imaging the role of amyloid in PD dementia

and dementia with Lewy bodies. Curr Neurol Neurosci

Rep 2014;14:472. Crossref

7. Chiba Y, Fujishiro H, Ota K, et al. Clinical profiles of

dementia with Lewy bodies with and without Alzheimer’s disease-like hypometabolism. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry

2015;30:316-23. Crossref

8. Killen A, Flynn D, De Brún A, et al. Support and information

needs following a diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies.

Int Psychogeriatr 2016;28:495-501. Crossref

9. Chiu FK, Lee HC, Chung WS, Kwong PK. Reliability and

validity of the Cantonese version of Mini-Mental State

Examination: a preliminary study. J Hong Kong Coll

Psychiatr 1994;4(2 Suppl):S25-8.

10. Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current

version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993;43:2412-4. Crossref

11. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A

new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in

longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic

Dis 1987;40:373-83. Crossref

12. Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S,

Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory:

comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in

dementia. Neurology 1994;44:2308-14. Crossref

13. Collin C, Wade DT, Davies S, Horne V. The Barthel ADL

Index: a reliability study. Int Disabil Stud 1988;10:61-3. Crossref

14. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The

diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease:

recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic

guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement

2011;7:263-9. Crossref

15. Smith R. Validation and reliability of the Elderly Mobility

Scale. Physiotherapy 1994;80:744-7. Crossref

16. Berg KO, Wood-Dauphinee SL, Williams JI, Maki

B. Measuring balance in the elderly: validation of an

instrument. Can J Public Health 1992;83 Suppl 2:S7-11.

17. Londos E, Hanxsson O, Alm Hirsch I, Janneskog A, Bülow

M, Palmqvist S. Dysphagia in Lewy body dementia—a

clinical observational study of swallowing function by

videofluoroscopic examination. BMC Neurol 2013;13:140. Crossref

18. Rosenbek JC, Robbins JA, Roecker EB, Coyle JL, Wood

JL. A penetration-aspiration scale. Dysphagia 1996;11:93-8. Crossref

19. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. NPUAP pressure

injury stages. Available from: http://www.npuap.org/resources/educational-and-clinical-resources/npuap-pressure-injury-stages/. Accessed 7 May 2016.

20. Galvin JE. Improving the clinical detection of Lewy body

dementia with the Lewy body composite risk score.

Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2015;1:316-24. Crossref

21. Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rüb U, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur

EN, Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic

Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 2003;24:197-211. Crossref

22. Takemoto M, Sato K, Hatanaka N, et al. Different clinical

and neuroimaging characteristics in early stage Parkinson’s disease with dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies. J

Alzheimers Dis 2016;52:205-11. Crossref

23. Liu S, Jin Y, Shi Z, et al. The effects of behavioral

and psychological symptoms on caregiver burden in

frontotemporal dementia, Lewy body dementia, and

Alzheimer’s disease: clinical experience in China. Aging

Ment Health 2016 Feb 16:1-7. Epub ahead of print. Crossref

24. Leggett AN, Zarit S, Taylor A, Galvin JE. Stress and burden

among caregivers of patients with Lewy body dementia.

Gerontologist 2011;51:76-85. Crossref

25. Imamura T, Hirono N, Hashimoto M, et al. Fall-related

injuries in dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and

Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol 2000;7:77-9. Crossref

26. Kudo Y, Imamura T, Sato A, Endo N. Risk factors for falls in

community-dwelling patients with Alzheimer’s disease and

dementia with Lewy bodies: walking with visuocognitive

impairment may cause a fall. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord

2009;27:139-46. Crossref

27. Alagiakrishnan K, Bhanji RA, Kurian M. Evaluation and

management of oropharyngeal dysphagia in different types

of dementia: a systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr

2013;56:1-9. Crossref

28. Jethwa KD, Onalaja O. Advance care planning and

palliative medicine in advanced dementia: a literature

review. BJPsych Bull 2015;39:74-8. Crossref

29. Molenaar JP, Wilbers J, Aerts MB, et al. Sudden death: an

uncommon occurrence in dementia with Lewy bodies. J

Parkinsons Dis 2016;6:53-5. Crossref