Hong Kong Med J 2018 Apr;24(2):119–27 | Epub 10 Apr 2018

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj176831

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Willingness for deceased organ donation under different

legislative systems in Hong Kong: population-based cross-sectional survey

TK Cheung, BSc; TC Cheng, BSc; LY Wong, BSN, MPH,

PhD

The Jockey Club School of Public Health and

Primary Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales

Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof LY Wong (lywong@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Under the current

opt-in system, the deceased organ donation rate remains low in Hong

Kong. An opt-out system and an opt-in system combined with organ

allocation priority (ie, priority to donors as transplant recipients)

have been proposed to encourage willingness among the general population

towards deceased organ donation. This study aimed to compare

willingness, and its determinants, across these three legislative

systems.

Methods: A random telephone

survey of Hong Kong permanent residents aged ≥18 years was conducted

between August and October 2016 using an anonymous questionnaire.

Willingness towards deceased organ donation was compared between the

legislative systems with McNemar’s test. Determinants of willingness

were tested by logistic regression.

Results: The proportion of those

willing to consider deceased organ donation under the current opt-in

system would significantly increase after combining it with allocation

priority (64.5% vs 73.4%; P=0.018). “Fairness or reciprocity” was the

major reported reason underlying the increase. In contrast,

willingness would decrease after introducing the opt-out

system (60.1%), although not significantly (P=0.336). The reduction

might be attributable to a “belief of being forced to donate”. Under the

allocation priority system, reduced willingness to donate was associated

with advanced age, lower educational attainment, and lower monthly

household income. Under the opt-out system, reduced willingness was

associated with being married, having a lower household income, and

distrust of local government.

Conclusions: An opt-in system

with allocation priority could induce willingness to donate, whereas an

opt-out system may reduce willingness. The findings have implications

for policy-making and promotion of organ donation.

New knowledge added by this study

- Introducing organ allocation priority to the current opt-in system is expected to significantly increase willingness of the Hong Kong general population for deceased organ donation.

- Replacing the opt-in system by an opt-out system may cause a reduction in willingness to donate. A portion of registered donors (15.8%) and of the general population who were willing to donate organs under the current opt-in system (28.2%) said they were reluctant to stay in the donor pool under the proposed opt-out system.

- The present study can help health care policymakers anticipate public attitude towards implementing an opt-out system and its potential effectiveness.

- The findings support alternative legislative systems of deceased organ donation other than the opt-out system, such as an opt-in allocation priority system.

- Apart from modification of the legislative system for organ donation, the government should consider policies designed to motivate registering behaviour.

Introduction

Organ transplantation offers the best clinical

management for patients with end-stage organ failure. Since the first

successful kidney transplant in 1954,1

a number of studies have confirmed that organ transplantation provides the

best outcomes for survival,2

quality of life,3 and

cost-effectiveness.4 With advances

in surgical techniques and immunosuppressive drugs, organ donation has

also progressively improved over the decades. However, the low rate of

deceased organ donation is a universal problem. Different countries have

adopted different policy schemes to encourage deceased organ donation but

the donation rates vary.

Currently, Hong Kong adopts an opt-in legislative

system of organ donation, where an individual who is willing to donate

their organs after death is required to carry a signed donor card or

register online at the Central Organ Donation Register.5 However, the registration rate among the general

population is low and was about 11% in 2015.6

The actual number of deceased donors in the same year was only 5.8 per

million population, which is much lower than in other developed areas: for

example, Spain has a deceased donor rate of 34 per million population,

which is the world’s highest.7 As a

result, organ demand consistently outweighs supply, leading to a long

waiting list.8

The World Health Organization is urging every

country to advance their organ procurement programme.9 Two legislative systems have been proposed to increase

the donation rate: an opt-out system and an opt-in system with organ

allocation priority (allocation priority system).10

An opt-out system presumes an individual is a potential deceased donor

unless refusal has been expressed by ‘opting out’ of the donor pool. This

system can simplify registration procedures and is convenient for those

willing to donate organs. An opt-out system, however, does not

specifically indicate willingness.11

On the basis of empirical evidence from several European countries,

implementing an opt-out system can successfully raise awareness and

willingness for deceased organ donation12

and actual donation rates.11 13 14 15

An opt-in system with allocation priority is

another policy approach, in which individuals who have registered as a

deceased donor will gain priority points on the transplant waiting list. A

priority point is a reward for those who are willing to donate an organ

and who in turn gain preferential status for receiving a donor organ if

required.16 This system can

motivate the public to register as donors by providing them with a higher

chance of extending their own lives and address the perceived unfairness

of ‘free-riders’ who are willing to receive an organ but unwilling to

donate. Israel adopted this policy approach in the Organ Transplant Act of

2008 and illustrated its effectiveness by the number of signed donor cards

and actual donation rates.10 16 17

In light of the low deceased organ donation rate in

Hong Kong, the government is currently reviewing its donation policy and

is considering replacing the current opt-in system by an opt-out system.

However, introducing an opt-out system without public support may actually

reduce the donation rate,18 as it

did in Brazil and Singapore.6

Similarly, ethical issues of the allocation priority system may fuel

public opposition. On the one hand, it promotes a fair concept of

reciprocity.16 19 On the other hand, there is a perception that organ

allocation should be based not on an individual’s willingness to donate,

but solely on their medical needs.16

19 It is difficult to predict the

effectiveness of proposed legislative systems in Hong Kong on the basis of

experience elsewhere, and local analysis of these systems is limited. Only

one local study has examined the willingness to donate a kidney under an

opt-out system but the feasibility of allocation priority was not

included.20 In addition,

socio-economic and demographic determinants may influence willingness

towards deceased organ donation. A Malaysian study suggested that such

determinants may differ under different legislative systems.21 Interestingly, political viewpoint is also correlated

with willingness when a new legislative system is imposed.12 22 It is

thus important to explore these determinants when considering an opt-out

system or allocation priority system.

Study aims

This study aimed to explore whether a proposed

opt-out system or opt-in allocation priority system would increase public

willingness in Hong Kong towards deceased organ donation, and to examine

the association of socio-economic, demographic, and political determinants

with the willingness of deceased organ donation under different proposed

policies.

Methods

A cross-sectional telephone survey with a

structured questionnaire was conducted. The target population was Hong

Kong permanent residents who were aged ≥18 years, able to register as a

deceased organ donor, and able to speak Cantonese. On the basis of the

‘10k rule of thumb’,23 the minimum

sample size required to test the association between the willingness of

organ donation and the seven socio-demographic variables in this study was

about 200. Assuming a 0.05 type 1 error, the sample size would be able to

detect 15% and 20% significant differences in the proportions of persons

shifting from ‘unwilling’ to ‘willing’ to donate after proposing the

allocation priority system and opt-out system, respectively, both with at

least 80% power. With the assumption that 12% of landline telephone

numbers are valid and there would be a 30% response rate, a sample of

about 5600 telephone numbers was needed. A computerised random list of

5800 eight-digit residential telephone numbers (starting with ‘2’ and ‘3’,

the current telephone number system in Hong Kong) was generated.

Telephone interviews were held from 18:00 to 20:30

on every weekday and from 11:00 to 18:00 on every weekend to ensure

coverage of different demographics. The actual proportions of calls made

on weekdays and at weekends were 41.3% and 58.7%, respectively. Interviews

were conducted by the first two authors and each took about 5 to 7

minutes, including an introduction explaining the interview and obtaining

verbal consent. A maximum of three calls was made at different times on

different days before a telephone number was considered invalid. If more

than one family member in a household was eligible, the person whose next

birthday was closest to the interview date was invited to participate.

The questionnaire was developed from a literature

review and comprised 14 items in four sections: (1) current opt-in system;

(2) proposed opt-out system; (3) proposed opt-in allocation priority

system; (4) background information: socio-economic and demographic

characteristics and political views. Reasons underlying the willingness

under each legislative system were explored with open-ended questions. On

the basis of a pilot study of the questionnaire’s feasibility and wording,

involving 10 members of the general public, descriptions of the two

proposed systems were refined. Double-entry of data and data cleaning were

conducted by the authors. Ethics approval was granted by the Survey and

Behavioural Research Ethics Committee of The Chinese University of Hong

Kong.

All statistical analyses were performed with IBM

SPSS Statistics 24 (IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], USA). A descriptive summary of

characteristics of respondents compared with those of the targeted general

population24 was prepared.

Two-sided McNemar’s tests were used to compare willingness rates between

the current opt-in system and the opt-out system, as well as between the

current opt-in system and the allocation priority system. Univariate

logistic regression analyses were performed to explore associations

between each independent variable (demographics, socio-economic level, and

political view) and the dependent variable (willingness of deceased organ

donation) under the proposed opt-out and allocation priority systems,

separately. Significant independent variables were further tested by

multiple logistic regression analysis using the forced entry method.

P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. A qualitative content

analysis was also conducted by the first author to identify meaningful

units emerging from the open-ended questions for underlying reasons for

willingness to donate. The units were coded into categories based on the

findings and suggested by the literature review,6

16 17

25 and were checked independently

by the second author.

Results

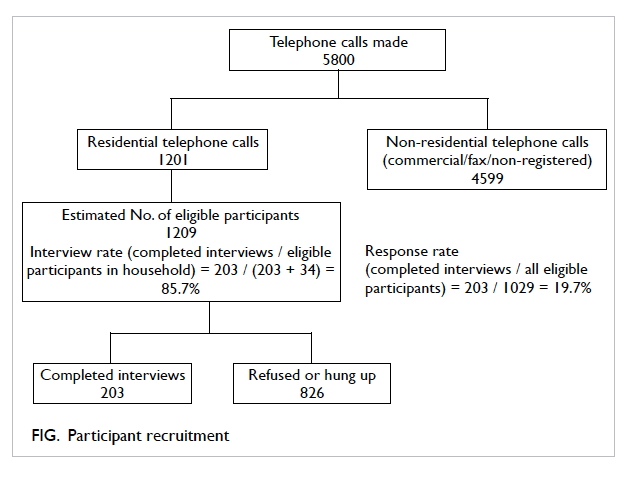

Telephone interview response rate

Telephone interviews took place between 2 August

and 18 October 2016 in Hong Kong. A total of 5800 households were

contacted and 203 respondents completed the questionnaire (response rate,

19.7%) (Fig).

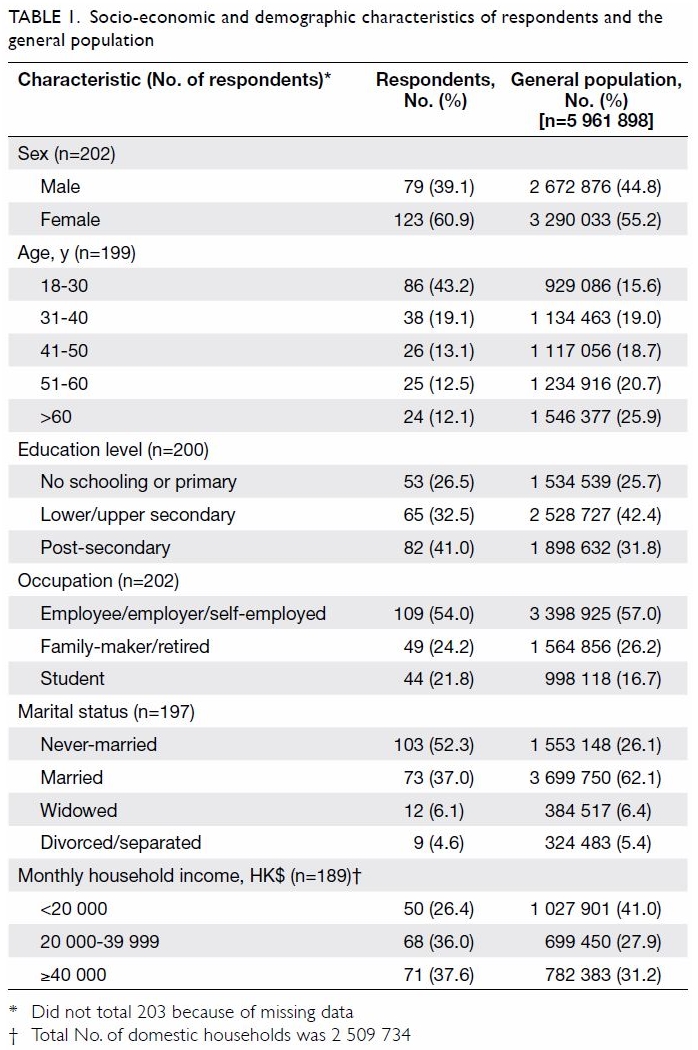

Characteristics of respondents

The majority of the respondents were female (60.9%

of 202), were aged 18 to 30 years (43.2% of 199), had a post-secondary

education (41.0% of 200), were employed (54.0% of 202), were never married

(52.3% of 197), and had a monthly household income of more than HK$40 000

(37.6% of 189). Compared with the general population, our study sample

contained smaller proportions who were male, older than 40 years, educated

to secondary level, or married, or who had a household income of <HK$20

000. (Table 1).

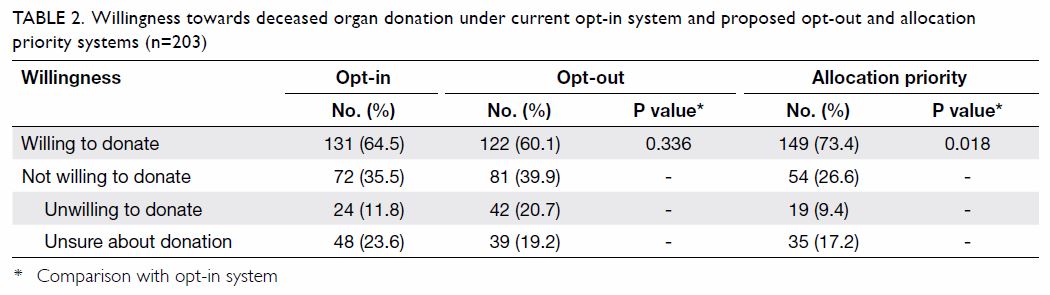

Willingness towards deceased organ donation

Under the current opt-in system, a majority of

respondents were willing to donate organs after death (64.5%), whereas

some were unwilling (11.8%) and others were unsure (23.6%) [Table

2]. Among those willing to donate, only 29.0% had registered as

deceased donors.

Table 2. Willingness towards deceased organ donation under current opt-in system and proposed opt-out and allocation priority systems (n=203)

After the opt-out system was proposed, 37.0% of

respondents who were unsure about donation or had been unwilling to donate

previously, reported a willingness to stay in the donor pool. However,

15.8% of registered donors and 28.2% of respondents who had originally

expressed a willingness to donate were reluctant to stay in the donor

pool. Overall, the willingness rate decreased from 64.5% under the current

opt-in system to 60.1% under the proposed opt-out system, although the

reduction was not statistically significant. In contrast, combining the

opt-in system with allocation priority motivated 64.8% of respondents

originally unwilling to donate to instead express a willingness. Only

11.4% of those originally willing to donate were demotivated. This

resulted in a statistically significant increase in the overall

willingness rate, from 64.5% under the current opt-in system to 73.4%

under the proposed allocation priority system (P=0.018) [Table

2].

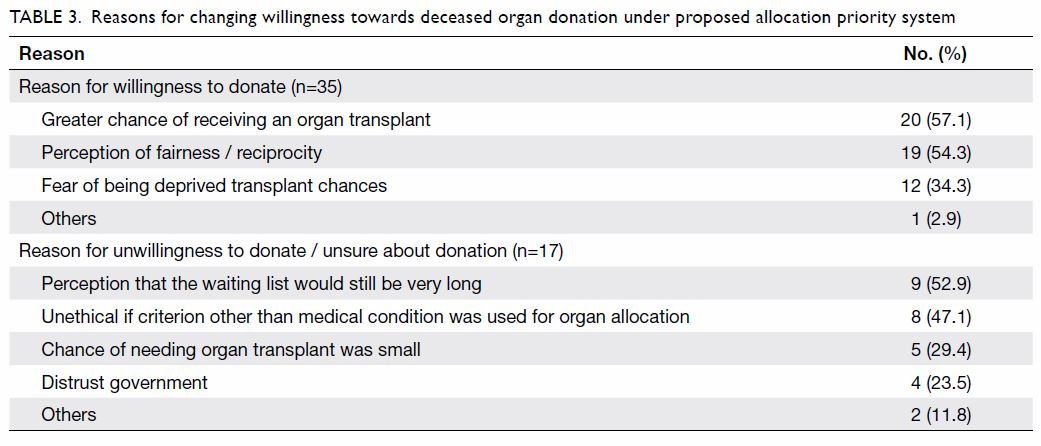

Under the allocation priority system, respondents

who changed their stance from unwilling to willing to donate (n=35) did so

largely because they perceived the system as a “fair or reciprocal” method

of organ allocation (57.1%). They believed they “had a greater chance of

receiving an organ transplant if registered” (54.3%). At the same time,

some respondents who had originally expressed a willingness to donate were

reluctant to do so under the priority system (n=17). They felt that the

preferential status was useless, as “the waiting list would be still very

long” (52.9%). Some also mentioned that it was “unethical” if criteria

other than medical condition were used for organ allocation (47.1%) [Table

3].

Table 3. Reasons for changing willingness towards deceased organ donation under proposed allocation priority system

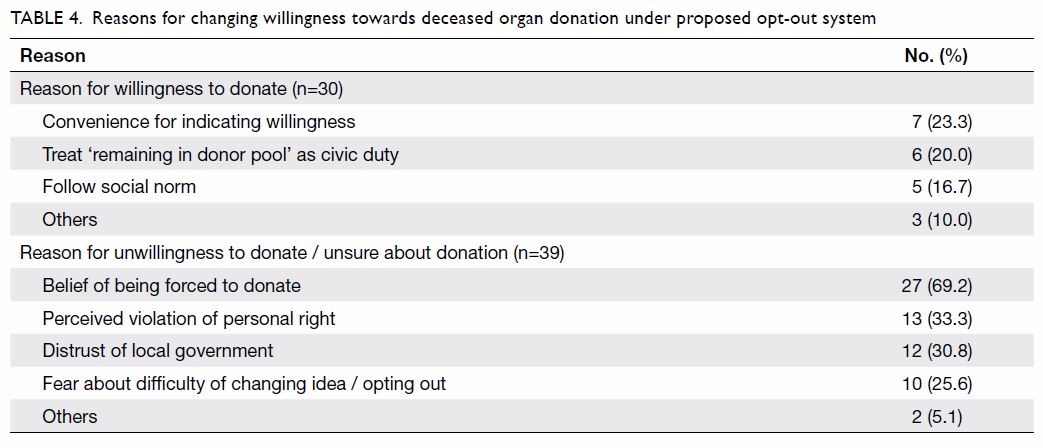

After the opt-out system was explained, those who

had been unsure about donor registration or unwilling to donate under the

opt-in system (n=30) were willing to stay in the donor pool because the

opt-out system offered them “convenience for indicating willingness”

(23.3%). Moreover, some believed that remaining in the donor pool was a

“civic duty” (20.0%). Conversely, many respondents who had been willing to

donate under the opt-in system chose to opt out (n=39), as they perceived

that under the system they were “forced to donate” (69.2%). “Distrust of

local government” was another reason (30.8%) [Table 4].

Table 4. Reasons for changing willingness towards deceased organ donation under proposed opt-out system

Determinants of willingness for deceased organ donation

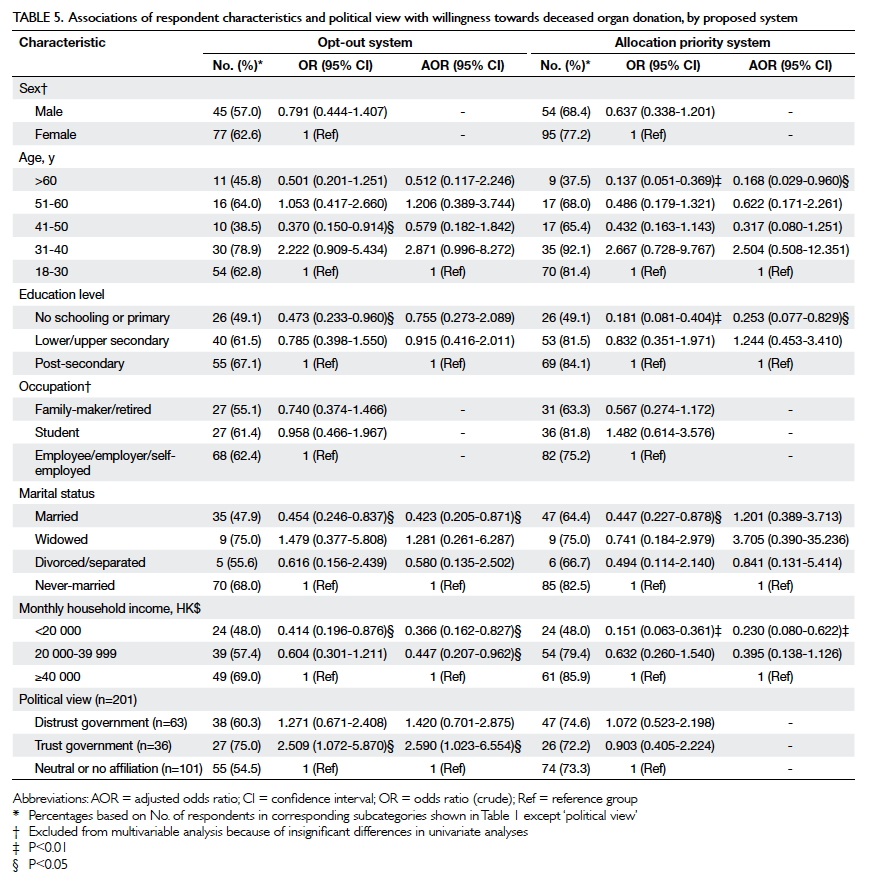

Associations between variables and willingness were

first tested by univariate logistic regression for each legislative system

(Table 5). Under the opt-out system, age, educational

attainment, monthly household income, marital status, and political view

were significantly associated with willingness. Under the allocation

priority system, age, educational attainment, monthly household income,

and marital status were the significant predictors. Sex and occupation

were not significantly associated with a willingness to donate under

either system.

Table 5. Associations of respondent characteristics and political view with willingness towards deceased organ donation, by proposed system

These significant predictors were further analysed

by multiple logistic regression. Under an opt-out system, respondents who

were married (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=0.423, 95% confidence interval

[CI]=0.205-0.871) or earned a monthly household income of <HK$20 000

(AOR=0.366, 95% CI=0.162-0.827) or HK$20 000-39 999 (AOR=0.447, 95%

CI=0.207-0.962) had a lower willingness to donate, whereas those who

trusted local government had a higher willingness (AOR=2.590, 95%

CI=1.023-6.554). Under an allocation priority system, lower willingness to

donate was associated with age over 60 years (AOR=0.168, 95%

CI=0.029-0.960), primary education level or no schooling (AOR=0.253, 95%

CI=0.077-0.829), and monthly household income of <HK$20 000 (AOR=0.230,

95% CI=0.080-0.622).

Discussion

Main findings

This study provides the first analysis of attitudes

towards different policies for deceased organ donation and related

determinants. We found that an allocation priority system would

significantly motivate respondents to donate their organs, similar to the

findings of an Israeli public telephone survey.17

The major underlying reason of “fairness or reciprocity” is aligned with

the concept of justice,19 as

organs are a scarce societal resource with a demand that heavily outweighs

the supply. The positive effect of a proposed priority incentive on

respondents’ willingness to donate may be related to possible organ

scarcity in the market with the extremely low donation rates in both

Israel and Hong Kong.7 In addition,

the concept of reciprocity might be derived from a moral duty of mutual

aid.26 Similar to many countries

that adopt the priority system, especially Singapore, Hong Kong treats

moral duty as a legislative foundation. Respondents might have agreed that

those who refuse to donate their organs (free-riders) should not receive

organs ahead of those who are willing to donate.17

Furthermore, respondents ,may also have been motivated by priority

incentives, providing them with a potential chance to extend their life.

This outcome is unsurprising, as it is the key feature of this allocation

priority system.16

With the increasing demand for organ

transplantation, the Hong Kong government has explored the feasibility of

an opt-out system. It is worth noting that a proposed opt-out system

caused a reduction in the willingness for deceased organ donation,

although not to a significant degree. This finding contradicts that

suggested by a recent Hong Kong study on kidney donation,20 which claimed that the willingness to donate would

rise significantly under an opt-out system. This inconsistency may be

attributable to an assumption made by that study, that those willing to

donate organs under the current opt-in system would remain willing under

an opt-out system. Yet, our study found that a large number of respondents

who were originally willing to donate changed to being unwilling to stay

in the donor pool. The switch was because many initially willing

respondents perceived that under an opt-out system, they were “being

forced” to donate. Nonetheless, the opt-out system has successfully

induced a willingness to donate in many European countries12 that also advocate personal liberties. According to a

European study, a societal environment was a prerequisite for the

government to justify an opt-out system that would limit citizens’

liberties.27 First, the opt-out

system can be imposed only when there are no less restrictive

alternatives. Yet, alternatives do exist, such as the allocation priority

system. Second, as in the present study, government popularity seems to be

another prerequisite condition that was lacking. Distrust of the local

government led some respondents to opt out.

Moreover, our study identifies determinants

associated with a willingness towards deceased organ donation. Respondents

with a lower education level and older age were less likely than others to

donate organs under an allocation priority system. These significant

factors might arise from a stronger traditional belief among the elderly

population of keeping a body intact after death,21

as well as a lower awareness of organ donation among those with less

education.28 The present study

also reveals that those who were married were more reluctant than

never-married people to donate under the opt-out system, because a married

person might need a partner’s consent before making a decision about

donating organs. Echoed by Malaysian and European studies, a trust in

government was associated with a higher willingness towards deceased organ

donation under the opt-out system.12

22

Lower monthly household income was associated with

lower willingness to donate organs under both systems. This association

may be because those with a higher income are more likely to promote a

supportive attitude towards organ donation.29

Although the significance of each determinant varied between the opt-out

system and the allocation priority system, strengths and directions of the

associations were similar across both. More importantly, these significant

determinants were also significant under the current opt-in system.30 Thus, regardless of the legislative system imposed,

determinants associated with willingness to donate appear the same.

Implications of findings

Policy-making

This study provides preliminary evidence of the

potential effectiveness of different legislative systems. In particular,

the study responds to the recent public controversy over the possible

introduction of an opt-out system in Hong Kong,31

and may help policymakers anticipate public opposition to such a system.

The government should first create a supportive societal environment and

gain public trust before its implementation.

At the same time, this study provides evidence to

support adding allocation priority to the current opt-in system in Hong

Kong. The findings offer policymakers new insight into alternative

legislative systems other than the opt-out system. Further evaluation of

the priority incentive or other policy instruments is suggested so that

policymakers can identify the best alternative.

The design of an administrative procedure to

motivate and facilitate registering behaviour should also be considered.

Similar to other local studies,6 30 this study found that the rate

of registration to donate was quite low among those currently willing. The

main reasons may be laziness and lack of knowledge about the registration

procedure.6 Thus, an individual’s

attitude towards donation is not necessarily aligned with registering

behaviour.12 32 In other words, combining the opt-in system with

allocation priority may not necessarily result in a higher registration

and donation rate in practice. Policymakers should consider measures that

will simplify the registration procedure. For example, in the United

States and the United Kingdom, driving license applicants are invited to

register as deceased organ donors.33

Education

Another recommendation stemming from this study is

the development of targeted promotion strategies when a new legislative

system is introduced. With an understanding of determinants of willingness

to donate, the Organ Donation Promotion Charter can target those who are

less willing to donate. By increasing knowledge and alleviating concerns

about procedures involved under the new legislative system, public

willingness is expected to increase.12

Promotional campaigns should also help build public trust in the

government for a smooth implementation of the new system.

Strengths and weaknesses

The strength of this study is the use of random

sampling for respondent recruitment. A random-digit dialling method was

used such that unlisted numbers were also contacted. Each residential

telephone number, therefore, had an equal selection probability. With a

95% residential fixed-line penetration rate,34

the sampling frame included most of the Hong Kong general population.

This study has several limitations. There may have

been selection bias (selective timing of telephone calls) and

self-selection bias (non-response after receiving phone calls). Our study

is not representative of the general population, as it has fewer

respondents who were male, of older age, educated to secondary level, of

lower socio-economic status, and married. In addition, without

standardised protocols, information bias may have arisen from recording

and classifying responses from the open-ended questions that asked for

underlying reasons for change in willingness. Examination of determinants

of the willingness to donate was also limited by the small sample size.

Subsequent surveys with a larger sample are recommended to investigate

socio-demographic variables as well as other possible factors, such as

chronic illness requiring an organ transplant in respondents and their

relatives or friends.

Conclusion

This study examined the impact of a proposed opt-in

system with organ allocation priority and an opt-out system on willingness

towards deceased organ donation among the Hong Kong general population. An

allocation priority system could induce willingness to donate. At the same

time, the study provides discouraging evidence for the effectiveness of an

opt-out system. These findings have implications for policy-making and

targeted education. More research is needed to study alternative

legislative systems to solve the crisis of organ shortage in Hong Kong.

Acknowledgement

We thank Ms Yuen-Fan Tong for her support and

experience in the development of the questionnaire.

Declaration

The authors have no conflicts of interest to

disclose.

References

1. Matesanz R, Dominguez-Gil B. Strategies

to optimize deceased organ donation. Transplant Rev 2007;21:177-88. Crossref

2. Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, et al.

Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis

awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant.

N Engl J Med 1999;341:1725-30. Crossref

3. Keown P. Improving quality of life—the

new target for transplantation. Transplantation 2001;72(12 Suppl):S67-74.

4. Winkelmayer WC, Weinstein MC, Mittleman

MA, Glynn RJ, Pliskin JS. Health economic evaluations: the special case of

end-stage renal disease treatment. Med Decis Making 2002;22:417-30.

5. Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Know more about centralised organ donation register. 2013.

Available from: https://www.organdonation.gov.hk/eng/knowmore.html.

Accessed 2 Nov 2016.

6. Hong Kong Ides Centre. A preliminary

study on deceased organ donation in Hong Kong. 2015. Available from:

http://www.ideascentre.hk/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2009/02/Final-Report-for-Organ-Donation-TC.pdf.

Accessed 2 Nov 2016.

7. International Registry in Organ Donation

and Transplantation. 2015. Available from: http://www.irodat.org/.

Accessed 2 Nov 2016.

8. Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Statistics (milestones of Hong Kong organ transplantation).

2016. Available from:

https://www.organdonation.gov.hk/eng/statistics.html. Accessed 2 Nov 2016.

9. Rodriguez-Arias D, Wright L, Paredes D.

Success factors and ethical challenges of the Spanish Model of organ

donation. Lancet 2010;376:1109-12. Crossref

10. Zúñiga-Fajuri A. Increasing organ

donation by presumed consent and allocation priority: Chile. Bull World

Health Organ 2015;93:199-202. Crossref

11. Johnson EJ, Goldstein D. Medicine. Do

defaults save lives? Science 2003;302:1338-9. Crossref

12. Mossialos E, Costa-Font J, Rudisill C.

Does organ donation legislation affect individuals’ willingness to donate

their own or their relative’s organs? Evidence from European Union survey

data. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:48. Crossref

13. Rithalia A, McDaid C, Suekarran S,

Myers L, Sowden A. Impact of presumed consent for organ donation on

donation rates: a systematic review. BMJ 2009;338:a3162. Crossref

14. Abadie A, Gay S. The impact of

presumed consent legislation on cadaveric organ donation: a cross-country

study. J Health Econ 2006;25:599-620. Crossref

15. Gimbel RW, Strosberg MA, Lehrman SE,

Gefenas E, Taft F. Presumed consent and other predictors of cadaveric

organ donation in Europe. Prog Transplant 2003;13:17-23. Crossref

16. Cronin AJ. Points mean prizes:

priority points, preferential status and directed organ donation in

Israel. Isr J Health Policy Res 2014;3:8. Crossref

17. Siegal G. Making the case for directed

organ donation to registered donors in Israel. Isr J Health Policy Res

2014;3:1. Crossref

18. Institute of Medicine. Presumed

consent. In: Childress FJ, Liverman TC, editors. Organ Donation:

Opportunities for Action. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press;

2006: 214.

19. Chandler JA. Priority systems in the

allocation of organs for transplant: should we reward those who have

previously agreed to donate. Health Law J 2005;13:99-138.

20. Chan TK, Cowling BJ, Tipoe GL. A

public opinion survey: is presumed consent the answer to kidney shortage

in Hong Kong? BMJ Open 2013;3.pii:e002013. Crossref

21. Tumin M, Tafran K, Mutalib MA, et al.

Demographic and socioeconomic factors influencing public attitudes toward

a presumed consent system for organ donation without and with a priority

allocation scheme. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1713. Crossref

22. Tumin M, Noh A, Jajri I, Chong CS,

Manikam R, Abdullah N. Factors that hinder organ donation:

religio-cultural or lack of information and trust. Exp Clin Transplant

2013;11:207-10. Crossref

23. Troutt MD. Regression, 10k rule of

thumb for. In: Kotz S, Campbell RB, Balakrishnan N, Vidakovic B, Johnson

NL, editors. Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences. John Wiley & Sons,

Inc; 2004:7098.

24. Census and Statistics Department, Hong

Kong SAR Government. By-census results. 2016. Available from:

http://www.bycensus2016.gov.hk/en/bc-index.html. Accessed 2 Nov 2016.

25. Lavee J, Brock DW. Prioritizing

registered donors in organ allocation: an ethical appraisal of the Israeli

organ transplant law. Curr Opin Crit Care 2012;18:707-11. Crossref

26. Peters DA. A Unified approach to organ

donor recruitment, organ procurement, and distribution. J Law Health

1988-1989;3:157-87.

27. Verheijde JL, Rady MY, McGregor JL,

Friederich-Murray C. Enforcement of presumed-consent policy and

willingness to donate organs as identified in the European Union Survey:

the role of legislation in reinforcing ideology in pluralistic societies.

Health Policy 2009;90:26-31. Crossref

28. Riyanti S, Hatta M, Norhafizah S, et

al. Organ donation by sociodemographic characteristics in Malaysia. Asian

Soc Sci 2014;10:265-72.

29. Wong LP. Knowledge, attitudes,

practices and behaviors regarding deceased organ donation and

transplantation in Malaysia’s multi-ethnic society: a baseline study. Clin

Transplant 2011;25:E22-31. Crossref

30. Surveillance and Epidemiology Branch,

Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Behavioural risk factor survey (April 2011): main report.

2012. Available from: http://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/brfs_2011apr_en.pdf.

Accessed 2 Nov 2016.

31. Tsang E. Hong Kong to discuss organ

donation opt-out scheme following death of girl awaiting double lung

transplant. South China Morning Post. 2015 Oct 9.

32. Ugur ZB. Does presumed consent save

lives? Evidence from Europe. Health Econ 2015;24:1560-72. Crossref

33. Buckley TA. The shortage of solid

organs for transplantation in Hong Kong: part of a worldwide problem. Hong

Kong Med J 2000;6:399-408.

34. Office of the Communications

Authority, Hong Kong SAR Government. Key communications statistics. 2016.

Available from:

http://www.ofca.gov.hk/en/media_focus/data_statistics/key_stat/. Accessed

2 Nov 2016.