Sudden arrhythmia death syndrome in young victims: a five-year retrospective review and two-year prospective molecular autopsy study by next-generation sequencing and clinical evaluation of their first-degree relatives

Hong

Kong Med J 2019 Feb;25(1):21–9 | Epub 23 Jan 2019

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Sudden arrhythmia death syndrome in young victims: a

five-year retrospective review and two-year prospective molecular autopsy

study by next-generation sequencing and clinical evaluation of their

first-degree relatives

Chloe M Mak, MD, FHKAM (Pathology)1#; NS

Mok, FHKAM (Medicine), FRCP (Edin)2#; HC Shum, MRCP (UK)3;

WK Siu, PhD, FHKAM (Pathology)1; YK Chong, FHKCPath, FHKAM

(Pathology)1; Hencher HC Lee, FRCPath, FHKAM (Pathology)1; NC

Fong, FHKAM (Paediatrics)4; SF Tong, MSc1; KW Lee,

BNurs2; CK Ching, FRCPA, FHKAM (Pathology)1; Sammy

PL Chen, FRCPA, FHKAM (Pathology)1; WL Cheung, MB, BS1;

CB Tso, FHKCPath3; WM Poon, FHKCPath, FHKAM (Pathology)3;

CL Lau, FHKAM (Medicine)3; YK Lo, FHKAM (Medicine)3;

PT Tsui, FHKAM (Medicine)2; SF Shum, FHKCPath, FHKAM

(Pathology)3; KC Lee, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Pathology)1

1 Department of Pathology, Princess

Margaret Hospital, Kwai Chung, Hong Kong

2 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics,

Princess Margaret Hospital, Kwai Chung, Hong Kong

3 Forensic Pathology Service, Department

of Health, Hong Kong

4 Department of Paediatrics,

Princess Margaret Hospital, Kwai Chung, Hong Kong

# The first two authors contributed

equally to the work.

Corresponding author: Dr NS Mok (mokns@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Objective: Sudden arrhythmia

death syndrome (SADS) accounts for about 30% of causes of sudden cardiac

death (SCD) in young people. In Hong Kong, there are scarce data on SADS

and a lack of experience in molecular autopsy. We aimed to investigate

the value of molecular autopsy techniques for detecting SADS in an East

Asian population.

Methods: This was a two-part

study. First, we conducted a retrospective 5-year review of autopsies

performed in public mortuaries on young SCD victims. Second, we

conducted a prospective 2-year study combining conventional autopsy

investigations, molecular autopsy, and cardiac evaluation of the

first-degree relatives of SCD victims. A panel of 35 genes implicated in

SADS was analysed by next-generation sequencing.

Results: There were 289 SCD

victims included in the 5-year review. Coronary artery disease was the

major cause of death (35%); 40% were structural heart diseases and 25%

were unexplained. These unexplained cases could include SADS-related

conditions. In the 2-year prospective study, 21 SCD victims were

examined: 10% had arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, 5%

had hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and 85% had negative autopsy. Genetic

analysis showed 29% with positive heterozygous genetic variants; six

variants were novel. One third of victims had history of syncope, and

14% had family history of SCD. More than half of the 11 first-degree

relatives who underwent genetic testing carried related genetic

variants, and 10% had SADS-related clinical features.

Conclusion: This pilot

feasibility study shows the value of incorporating cardiac evaluation of

surviving relatives and next-generation sequencing molecular autopsy

into conventional forensic investigations in diagnosing young SCD

victims in East Asian populations. The interpretation of genetic

variants in the context of SCD is complicated and we recommend its

analysis and reporting by qualified pathologists.

New knowledge added by this study

- This study provides important data on the prevalence and types of sudden arrhythmia death syndrome (SADS) among young victims of sudden cardiac death in an East Asian population.

- This is the first local feasibility study on the service model incorporating cardiac evaluation of surviving relatives and molecular autopsy by next-generation sequencing into the conventional forensic investigations.

- Genomic testing should be conducted on patients with cardiomyopathies and channelopathies.

- Clinical assessment should be provided for at-risk family members irrespective of genetic findings.

- Molecular autopsy together with conventional autopsy conducted by qualified pathologists should be applied to victims of SADS, sudden unexpected death in epilepsy, or sudden infant death syndrome.

Introduction

Sudden death is defined as death occurring within 1

hour of the onset of symptoms or within 24 hours of the victim being seen

alive.1 Sudden death due to an

underlying heart disease is known as sudden cardiac death (SCD). The

worldwide annual incidence of SCD is about 4 to 5 million cases per year.2 A tragic and devastating

complication of a number of heart diseases, SCD is most often unexpected

and has major implications for the surviving family and the community. The

majority of SCD cases in middle-aged and older individuals are caused by

coronary artery disease; however, SCD is rare in young people and the

causes are more diversified.3 4 Autopsy studies have shown no structural heart disease

was found in up to 30% of young SCD victims.5

6 7

8

Molecular autopsy was first described by Ackerman

et al9 in 1999, to determine the

cause of death in uncertain cases after conventional autopsy by genetic

analysis. Post-mortem genetic studies have shown that SCD in these victims

can be caused by fatal arrhythmias secondary to a group of inheritable

cardiac electrical disorders collectively known as sudden arrhythmia death

syndrome (SADS).10 11 12 13 14 These

include Brugada syndrome (BrS), long QT syndrome (LQTS), short QT

syndrome, catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT),

arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC), hypertrophic

cardiomyopathy (HCM), and other cardiomyopathies.

Because SADS-related conditions are genetic

diseases, there are two different approaches to identify SADS among young

sudden unexplained death (SUD) victims. The first approach involves

detailed clinical and targeted genetic examination of the surviving

relatives of SCD victims. Studies using this approach suggest that SADS

may account for approximately 40% of autopsy-negative sudden death in

young people.10 15 However, this approach may not be able to identify

subjects with concealed form of SADS due to incomplete penetrance and

variable expressivity of the pathological mutations. The second approach

is to perform molecular autopsy on SCD victims, which involves post-mortem

genetic testing for SADS. A landmark study on molecular autopsy by the

Mayo Clinic showed over one third of SCD cases hosted a presumably

pathogenic mutations of cardiac ion channel diseases.8 16 Thus a

combined approach using both cardiac evaluation of surviving relatives and

molecular autopsy on SUD victims should give a higher yield on elucidating

the underlying causes of SUD.

In Hong Kong, there are scarce data on the

prevalence and types of SADS underlying SCD or SUD in young people. The

present study aimed to investigate the prevalence and types of SADS in an

East Asian population, and to perform a pilot study on incorporating

cardiac evaluation of surviving relatives and molecular autopsy by

next-generation sequencing (NGS) into conventional forensic

investigations.

Methods

In the present study, first, we carried out a

5-year retrospective review of the records of all autopsies for young

sudden death victims performed in public mortuaries in Hong Kong. Second,

we conducted a 2-year study to determine the prevalence and types of SADS

as the underlying causes of SCD among local young victims through

conventional and molecular autopsy, and evaluated their first-degree

relatives.

Five-year retrospective review of autopsy records

The Forensic Pathology Service, Department of

Health, provides all public autopsy services for over 7 million people in

Hong Kong. We performed this retrospective review of the records of all

autopsies in public mortuaries for young sudden death victims (aged 5-40

years) between 1 January 2008 and 31 December 2012. Sudden death was

defined as death occurring within 1 hour of the onset of symptoms or

within 24 hours of the victim being seen alive.1

Sudden death victims were recruited into the study for a detailed review

of their autopsy records. Data including age, height, weight, sex,

circumstances of death, clinical history of cardiac disease, and

pathologic findings at autopsy were collected and analysed. Sudden death

victims whose deaths were caused by trauma, accidents, drowning, and drug

toxicity, and those whose autopsy records were either incomplete or not

accessible for retrospective review were excluded.

Two-year prospective study by conventional and

molecular autopsy

In this prospective study, young SCD victims (aged

5-40 years) were identified and recruited into the study by forensic

pathologists after a finding of either an inheritable arrhythmogenic

cardiomyopathy or no anatomical cause of death (including other structural

heart disease) on autopsy, and a negative toxicology screening. Clinical

history, including personal history of arrhythmic events and history

surrounding the sudden death event of the SCD victim was collected during

identification interviews with next-of-kin as far as possible by forensic

pathologists. DNA-friendly blood samples were collected for molecular

autopsy. Written informed consent for a molecular autopsy was obtained

from the next-of-kin of each victim. The first-degree relatives of the

victims were referred by forensic pathologists to the study centre for

genetic counselling and recruitment into the study. Clinical history,

including personal history of arrhythmic events and history surrounding

the sudden death event of the SCD victim was collected from family

members. All recruited first-degree relatives underwent clinical

evaluation including 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG), signal-averaged ECG,

echocardiogram, 24-hour Holter analysis and treadmill exercise testing.

Additional investigations were used only as required, such as flecainide

provocation testing (if BrS is suspected in subjects >18 years) and

targeted genetic screening (if positive molecular autopsy findings in the

index SUD victim). All first-degree relatives provided written informed

consent for these procedures and for publication of the results.

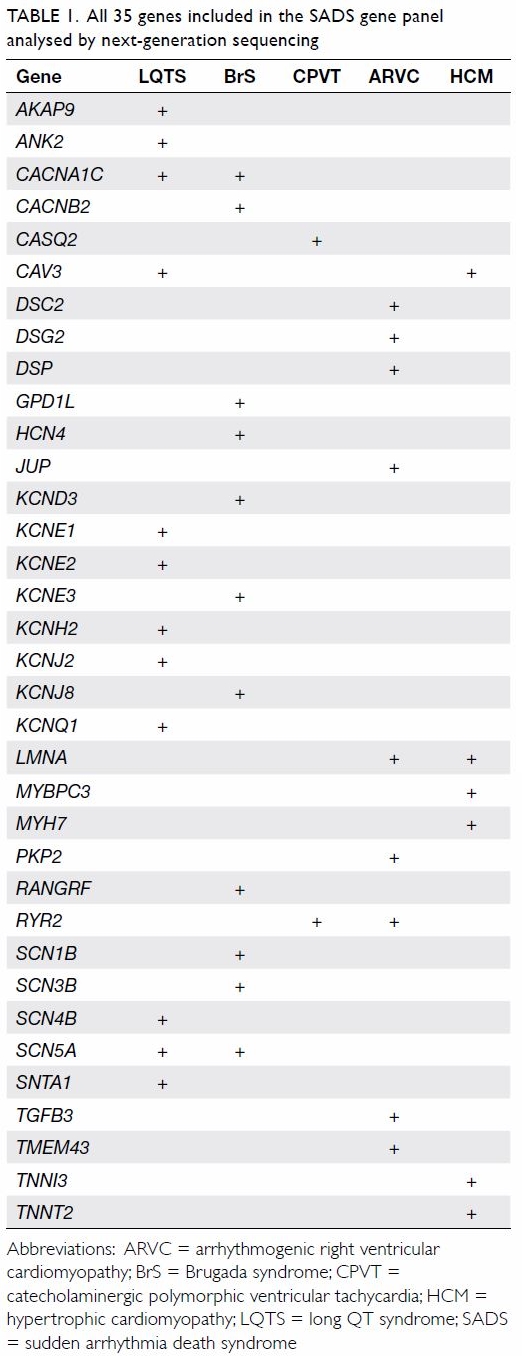

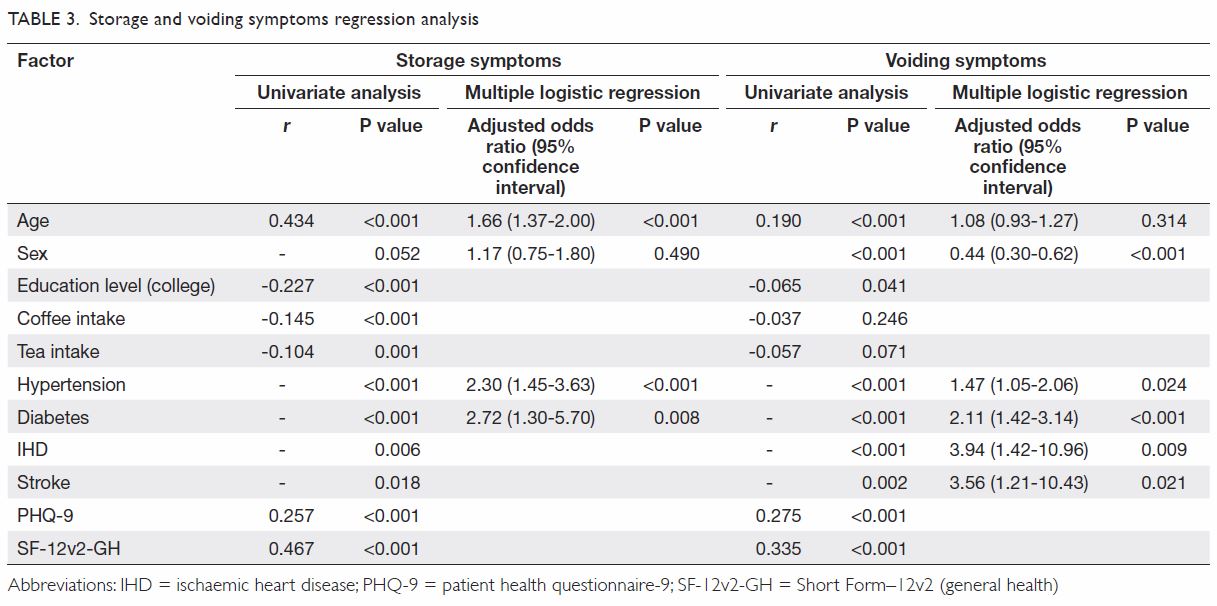

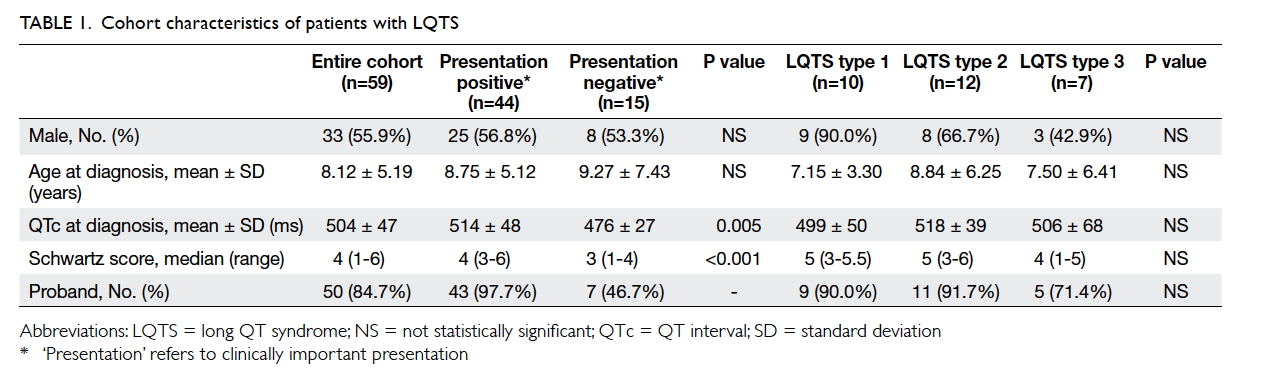

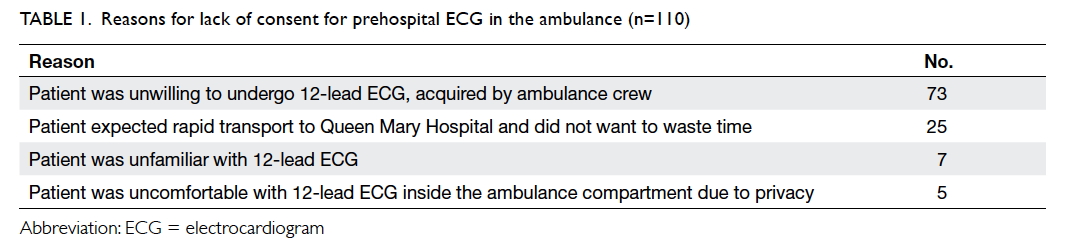

A panel of 35 genes implicated in SADS for BrS,

LQTS, short QT syndrome, CPVT, ARVC, and HCM was tested using NGS (Table

1). The NGS was performed using targeted gene capture technique on a

MiSeq Sequencing System (Illumina, Inc, San Diego [CA], United States).

Target regions of interest were restricted to the coding regions and the

10-bp flanking regions. Target rates indicated percentage of bases with a

minimum depth of coverage of 20×. Alignments to the February 2009

(GRCh37/hg19) human genome assembly and variant calls were generated using

dual pipelines, SoftGenetics NextGENe (v2.4.1) and an in-house one where

sequencing reads were aligned by Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (v0.7.5a-r405) to

hg19 genome and processed with picard-tools (v1.114). Local realignment

for indels and base quality recalibration were performed with Genome

Analysis Toolkit (GATK, v3.2). Variant calls were made with

UnifiedGenotyper (GATK v3.2). Only those genes included in the requested

gene panel were processed for variant calling. Variants identified were

annotated and analysed with VariantStudio (v2.2.1; Illumina, Inc); in

general, variants with an allele frequency of <0.1% for dominant

disorders or <1.0% for recessive disorders were reported. Pathogenic

and likely pathogenic variants were confirmed by Sanger sequencing; benign

and likely benign variants were not reported.

The genetic variant pathogenicity was established

according to the Practice Guidelines for the Interpretation and Reporting

of Unclassified Variants in Clinical Molecular Genetics by the Clinical

Molecular Genetics Society (http://

www.acgs.uk.com/media/774853/evaluation_and_reporting_of_sequence_variants_bpgs_june_2013_-_finalpdf.pdf).

Major criteria include degree of conservation, population allele

frequencies, co-segregation pattern, literature data, functional studies

and in silico prediction. The pathogenicity of novel missense variants was

analysed by PolyPhen-2, SIFT, MutationTaster and Assessing Pathogenicity

Probability in Arrhythmia by Integrating Statistical Evidence (https://cardiodb.org/APPRAISE/)

and that of novel splicing variants was by Splice Site Finder-like,

MaxEntScan, GeneSplicer and Human Splicing Finder, wherever appropriate.

Splicing variants were considered to be damaging if the score was more

than 10% lower than the wild-type prediction. Allele frequencies among

populations were as reported in the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD, http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/).

A diagnosis of SADS was established when molecular

autopsy in SCD victims identified a positive genetic variant implicated in

SADS or generally accepted clinical criteria for a particular disease were

fulfilled in the SCD victims or their first-degree relatives. The

descriptive statistics were analysed using Excel 2016 (Microsoft Corp,

Redmond [WA], United States).

Results

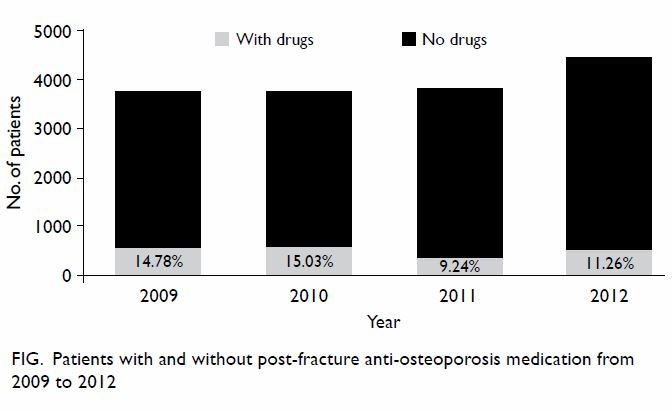

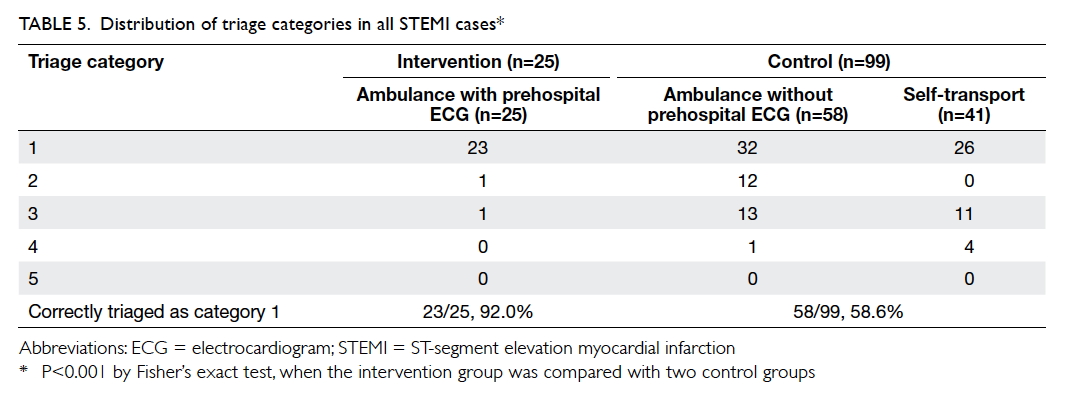

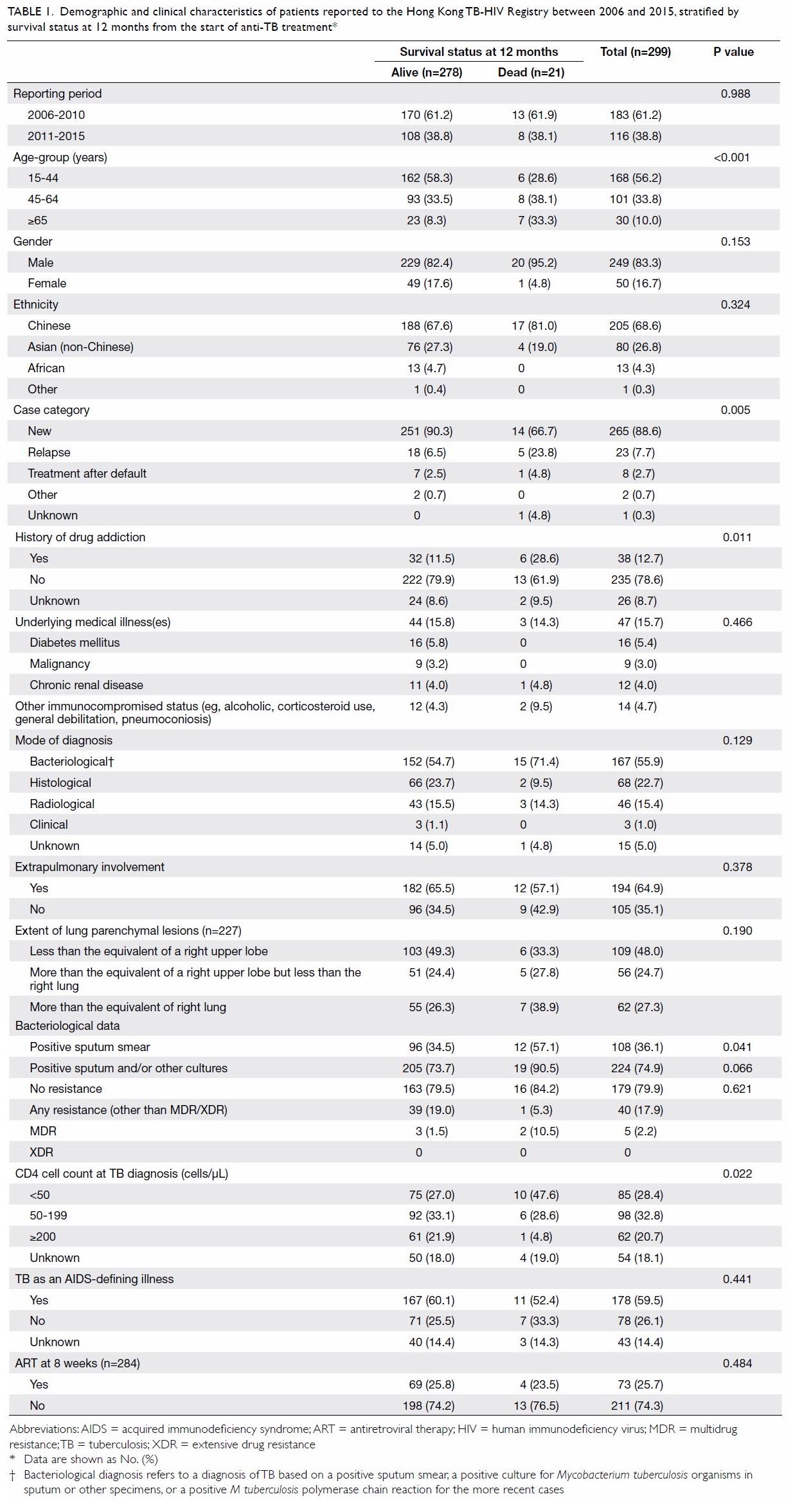

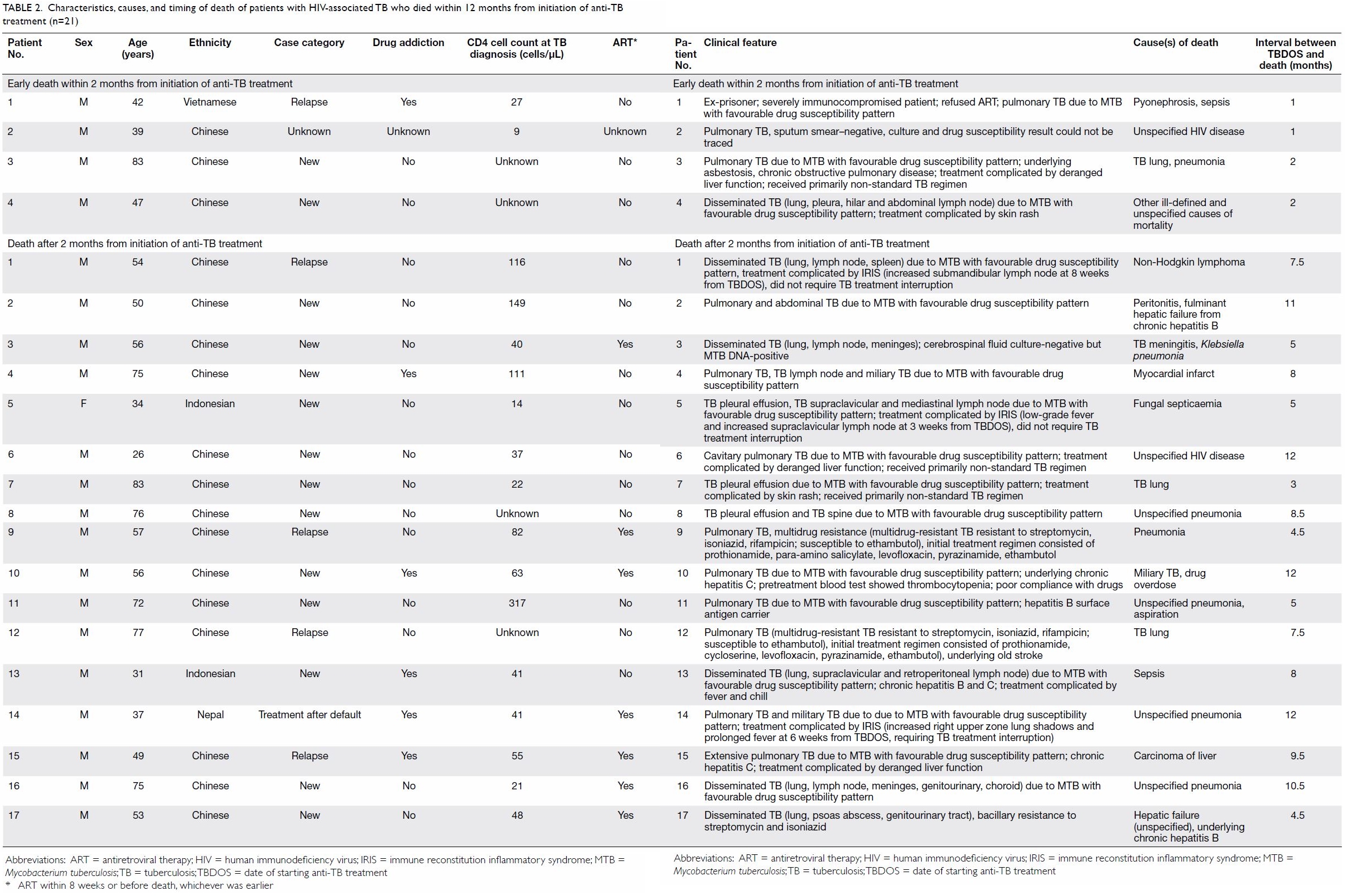

Five-year retrospective review of autopsy records

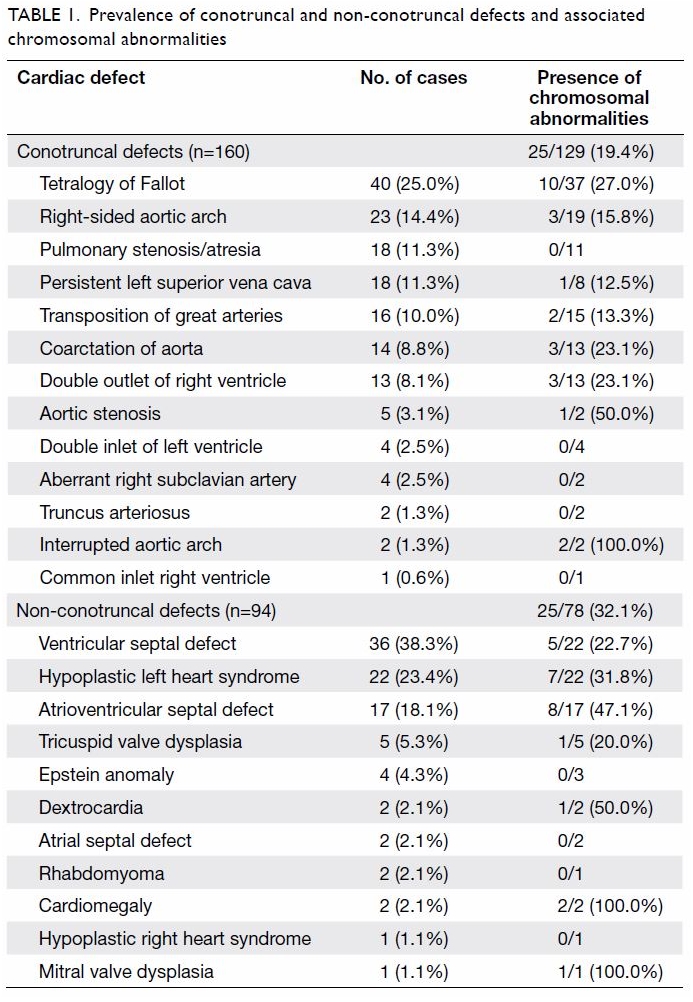

There were 17 187 autopsies performed during the

study period and 2748 (16%) deaths were aged 5 to 40 years. There were 420

sudden death victims. Among them, 289 (69%) were SCD (male:female

ratio=9:2). The median age was 32 years (range, 7-40 years). Coronary

artery diseases accounted for 35% of the causes of death; other causes of

death were aortic dissection (6%), myocarditis (6%), left ventricular

hypertrophy (4%), dilated cardiomyopathy (9%), other structural heart

diseases (9%), HCM (4%), ARVC (2%), and unexplained (25%).

Two-year study by conventional and molecular autopsy

There were 32 SCD victims aged 5 to 40 years

between 1 July 2014 and 30 June 2016 with a finding of either an

inheritable arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy or no anatomical cause of death

(including other structural heart disease) on autopsy and negative

toxicology results. Eleven individuals were excluded: two who had no Hong

Kong identity card and nine whose families refused consent. Finally, 21

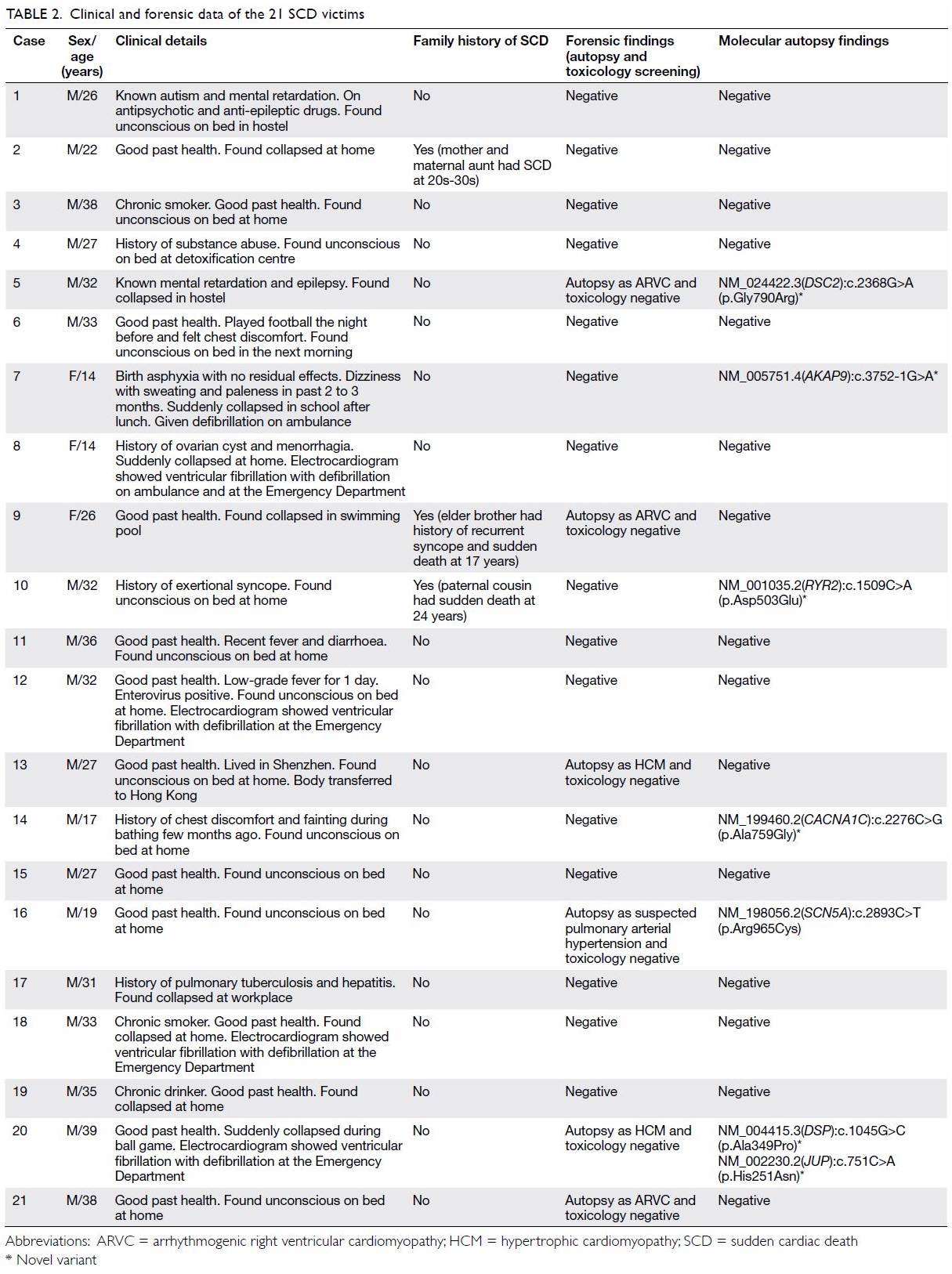

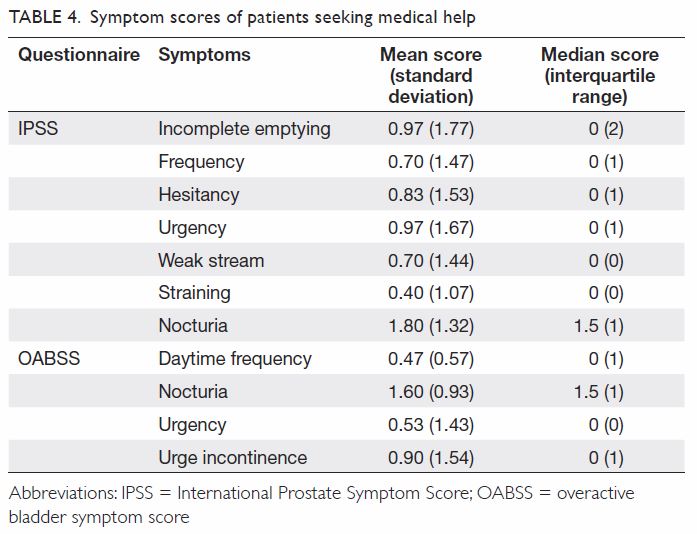

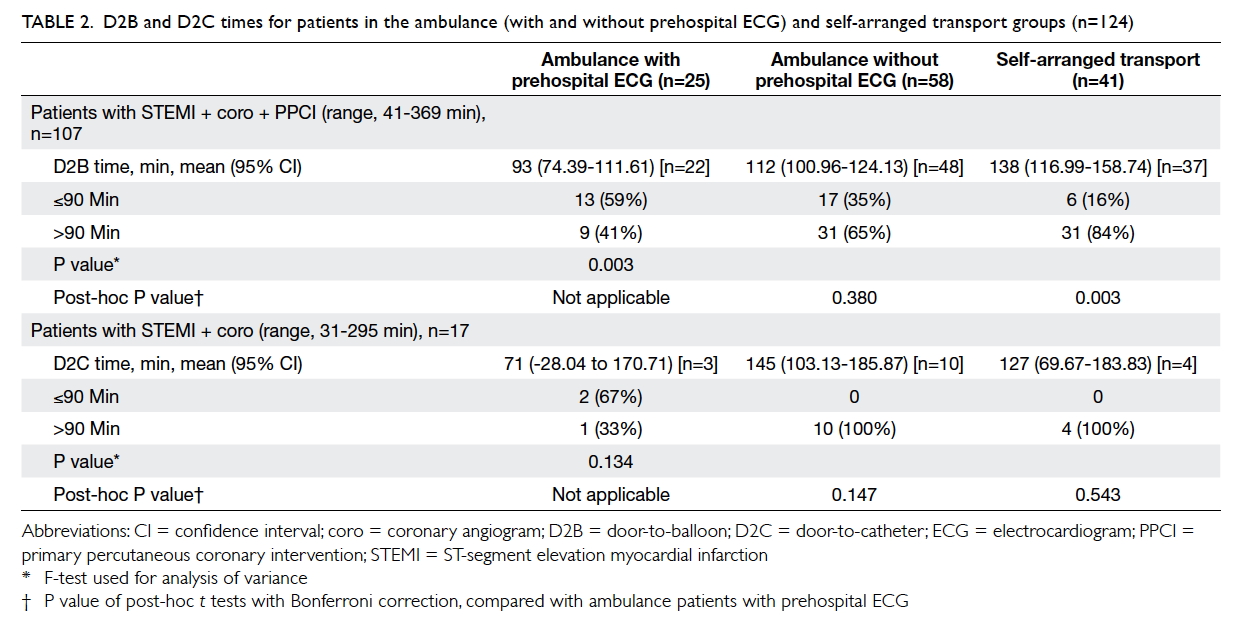

SCD victims (18 male, 3 female) were recruited into the study. Table

2 shows the clinical and forensic data of the 21 SCD victims. The

median age was 31 years (range, 14-39 years). From the conventional

autopsy, 18 (86%) were unrevealing; two (10%) SCD victims had ARVC and one

(5%) had HCM. The majority died during resting (48%) or sleeping (24%).

Only three SCD victims (14%) died during exercise. Three (14%) SCD victims

had family history of SCD and seven (33%) had a history of syncope. Many

(71%) of the SCD victims had unremarkable past health. Genetic analysis

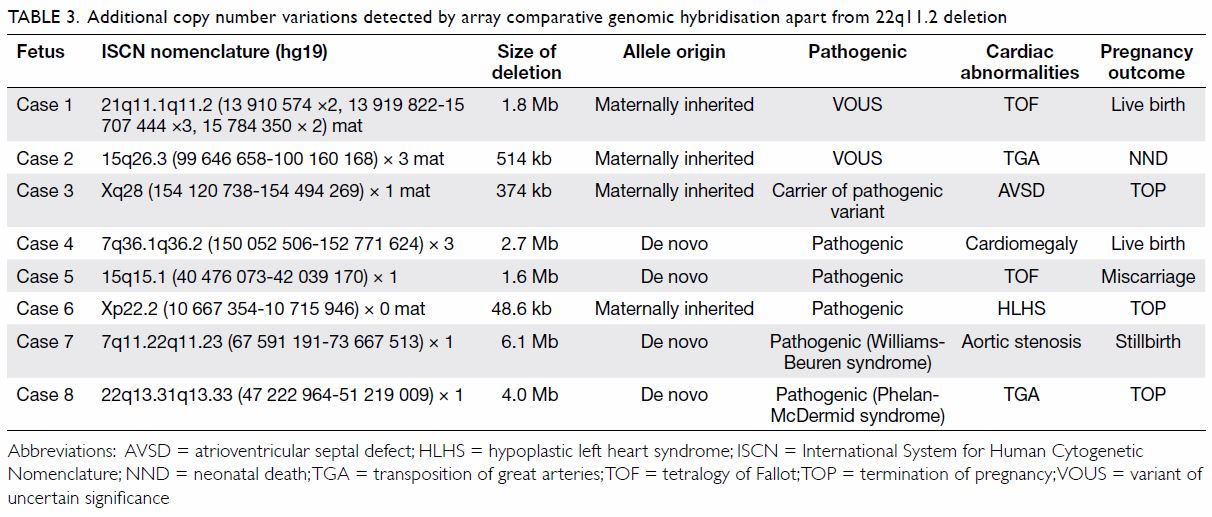

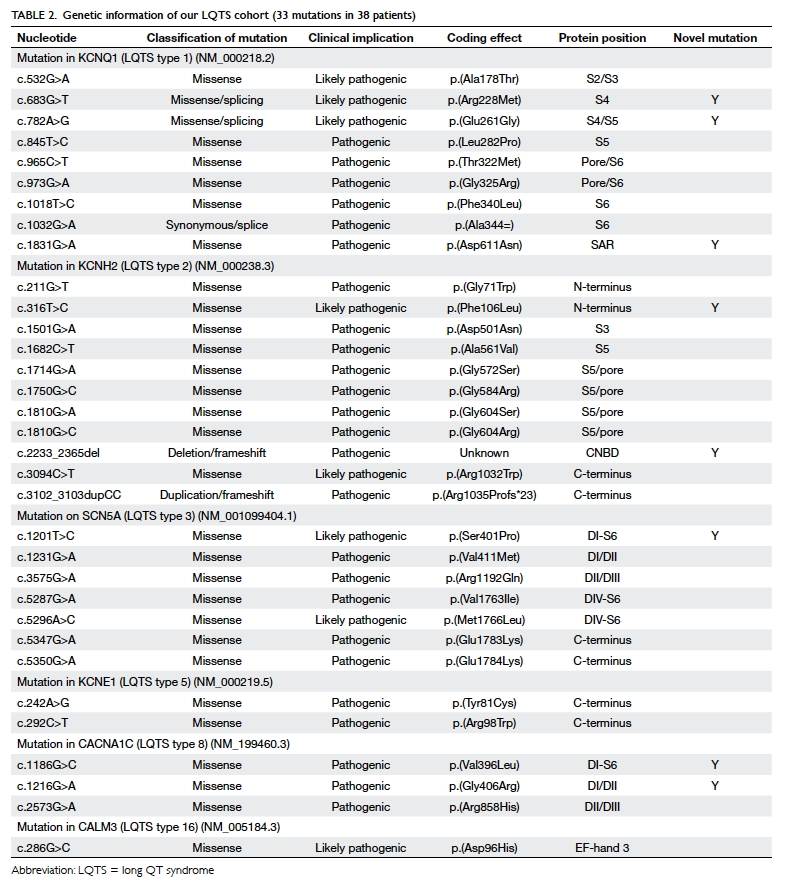

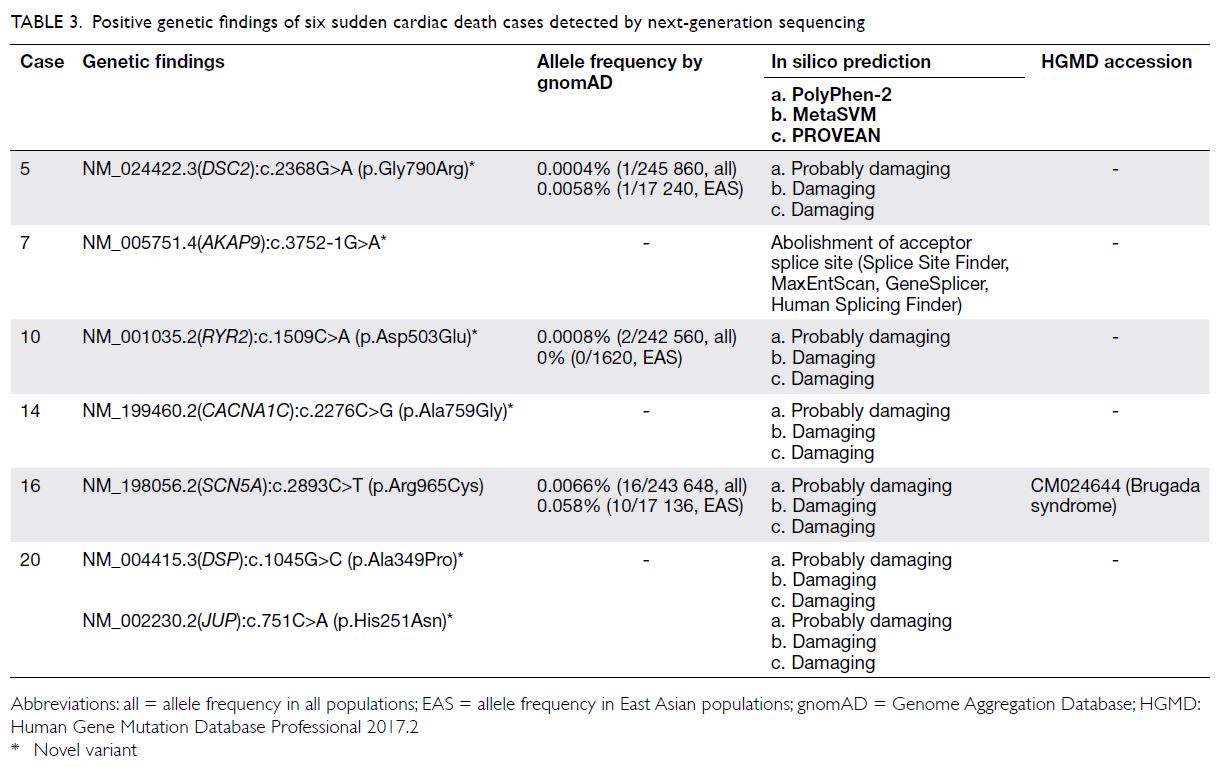

showed 29% with positive heterozygous genetic variants (Table

3). Seven variants were identified in seven genes, six variants of

which were novel. The genetic background was heterogeneous without any

common mutations found. Combining conventional and molecular autopsy

findings, the cause of death in 12 (57%) still remains unknown; cause of

death was confirmed in four (19%) as ARVC, in two (10%) as BrS, and one

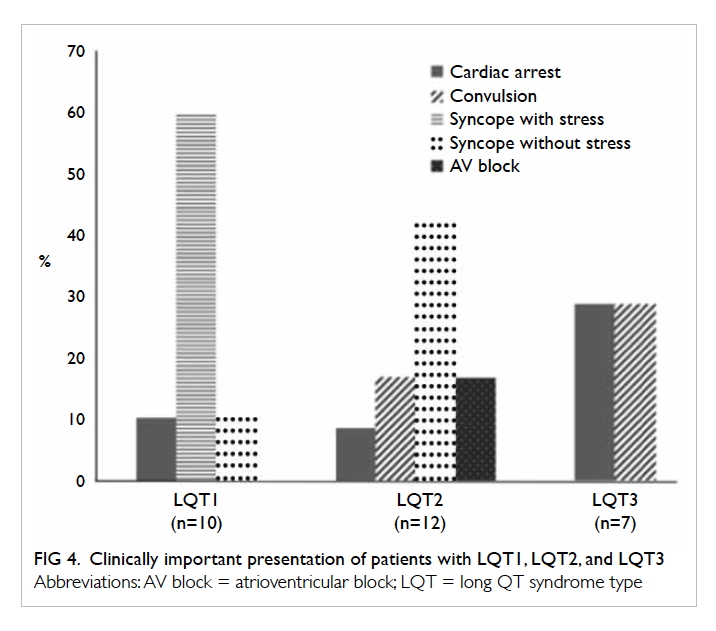

(5%) each in HCM, LQTS, and CPVT.

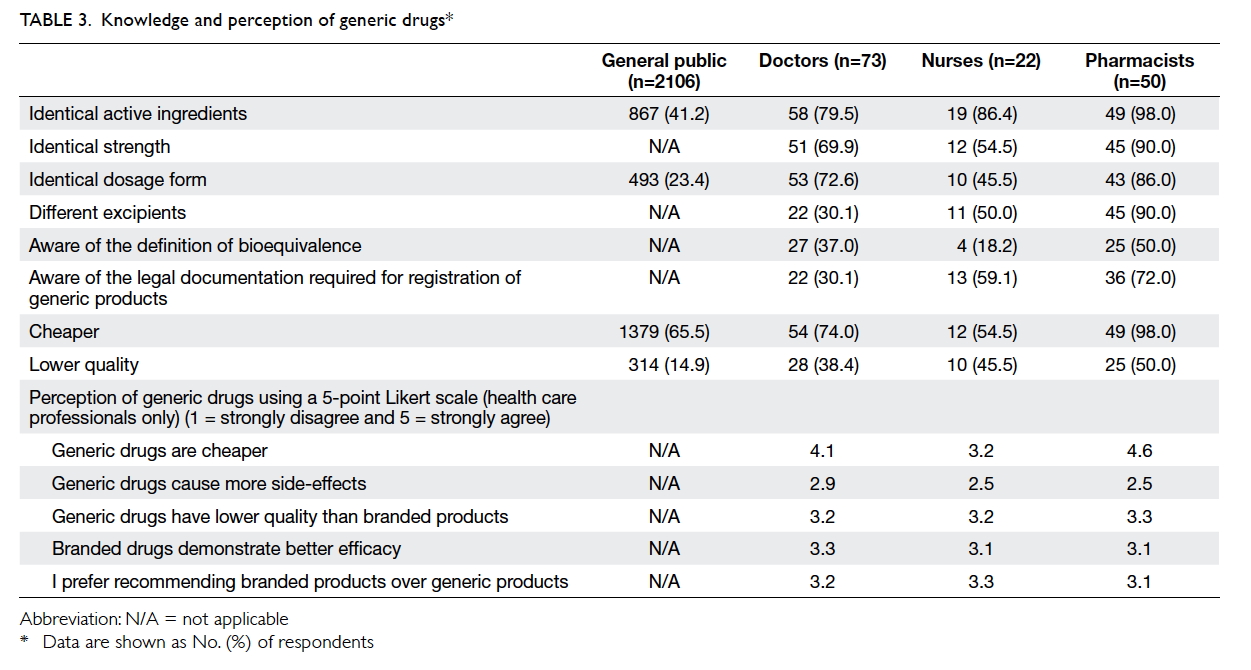

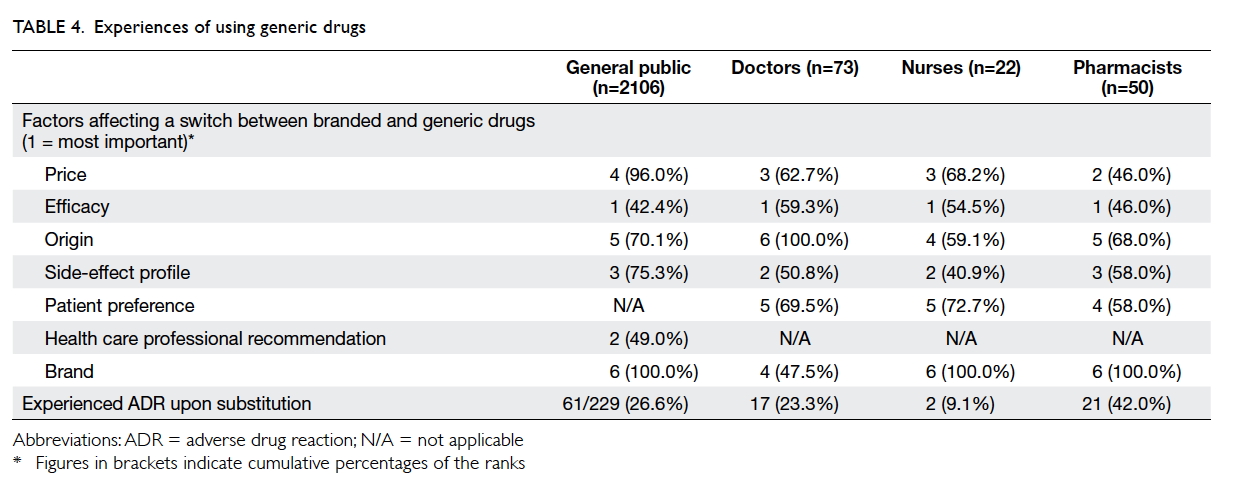

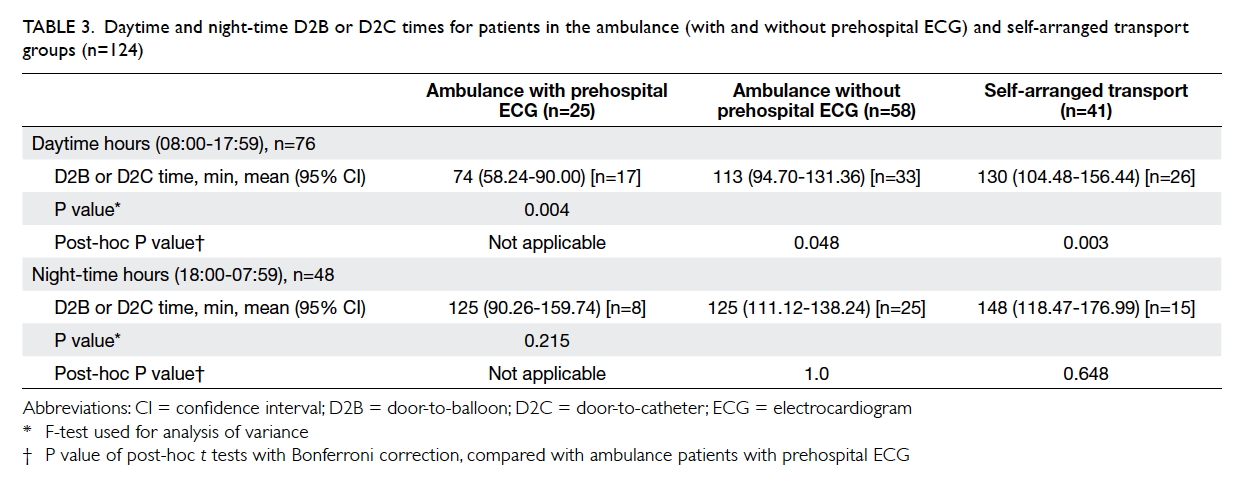

Table 3. Positive genetic findings of six sudden cardiac death cases detected by next-generation sequencing

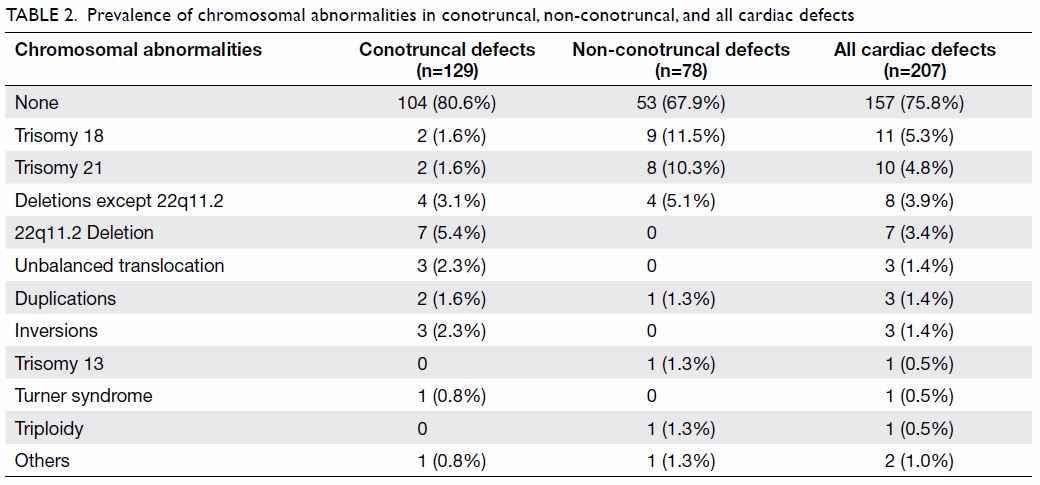

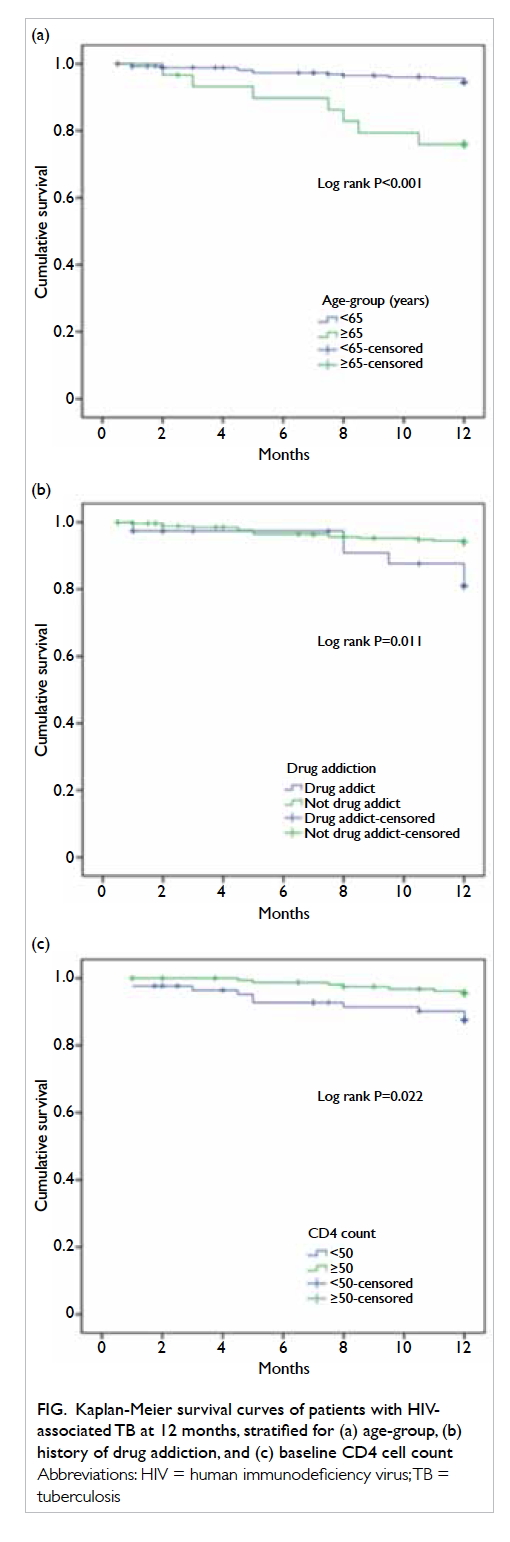

Overall, more than half of first-degree relatives

(6 of 11 individuals) who underwent genetic testing carried the positive

genetic variants. Among them, SADS-related clinical features were detected

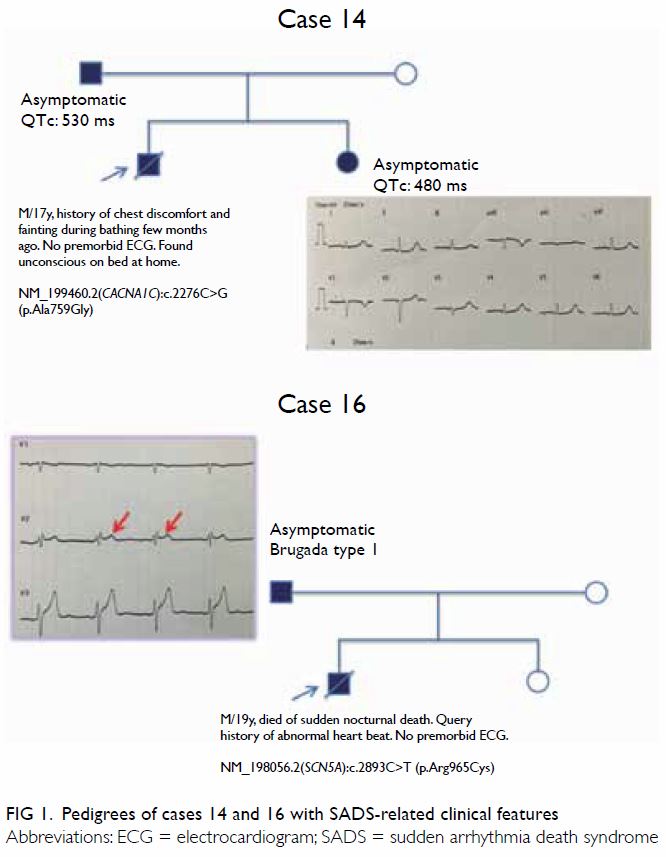

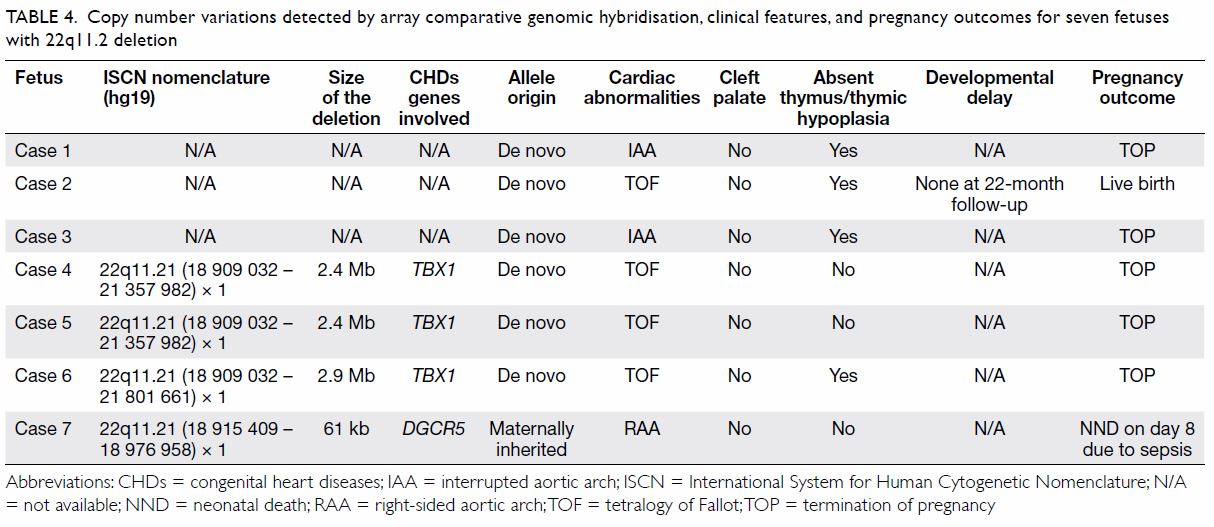

in three first-degree relatives from two families (cases 14 and 16). The

true clinical phenotype can sometimes be detected in surviving relatives

upon appropriate clinical evaluation, which in turn significantly aids the

interpretation of genetic findings. Cases 14 and 16 illustrate the

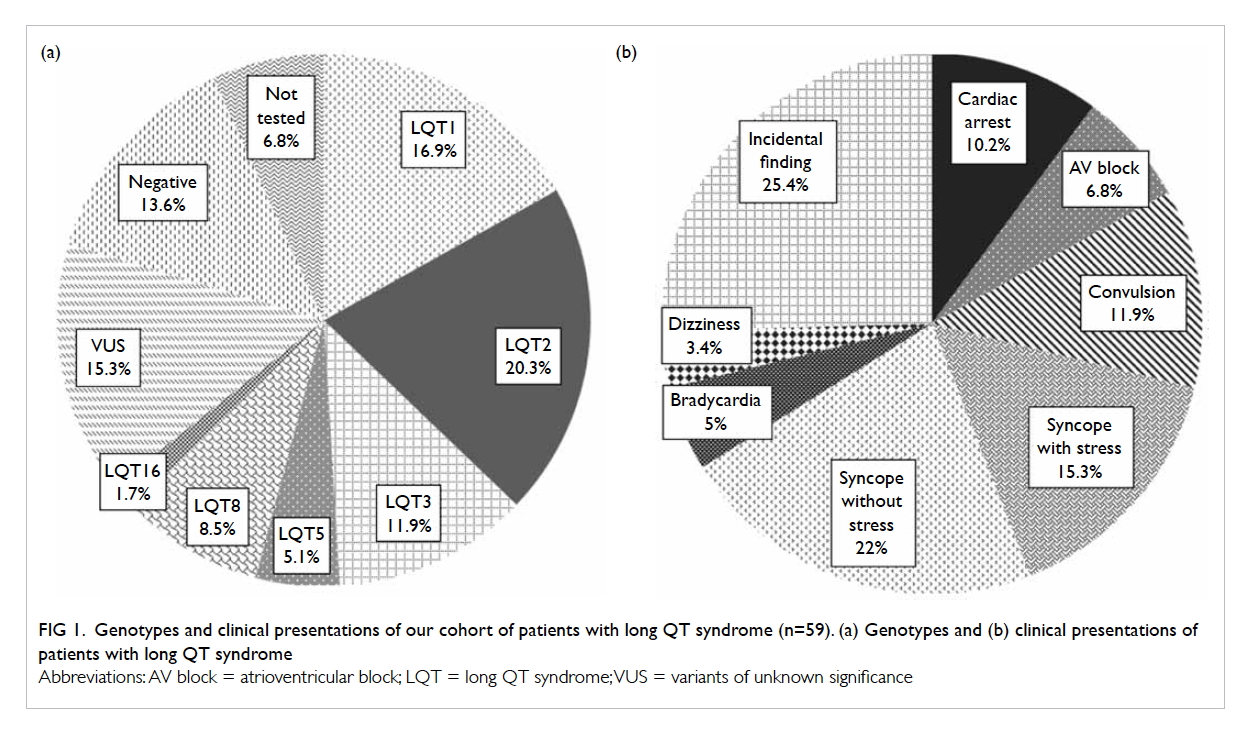

importance of this (Fig 1). The first-degree relatives of these two

cases showed SADS-related clinical features after cardiologist’s

assessment.

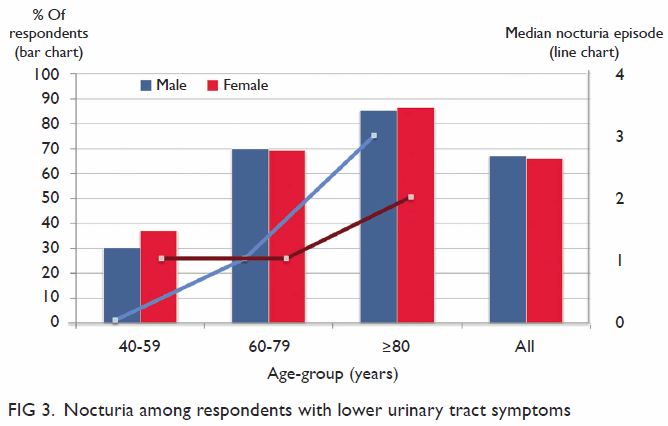

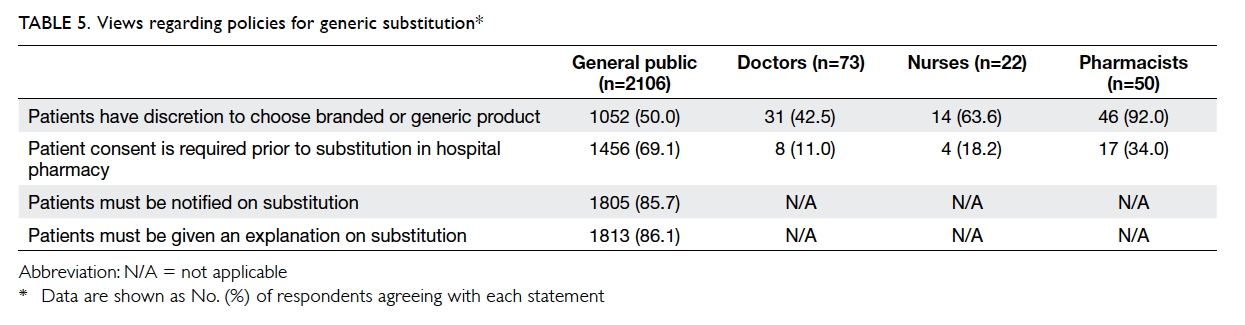

Case 14 was a 17-year-old male victim who died of

sudden nocturnal death. He had an episode of syncope few months prior to

his death but he did not seek medical attention. Family screening by

clinical evaluation found no structural heart disease but ECG revealed

prolonged QTc interval in his asymptomatic father and sister (530 ms and

480 ms, respectively) suggesting a diagnosis of LQTS (Fig

1). Molecular autopsy found heterozygous NM_199460.2(CACNA1C):c.2276C>G

NP_955630.2:p.(Ala759Gly). This novel variant is predicted to be damaging

and absent in the gnomAD. CACNA1C is the gene encoding for the

alpha-1c subunit of the type 1 voltage-dependent calcium channel involved

in the cardiac myocyte membrane polarisation. Its mutations have been

reported in BrS and LQTS.

Case 16 was a 19-year-old male victim who also died

of sudden nocturnal death. There was no known syncope or preceding

symptoms ahead of the collapse. He had history of abnormal heart beat,

although ECG was not done. His family history was unremarkable. Autopsy

revealed pulmonary hypertension. Molecular autopsy detected heterozygous

NM_198056.2(SCN5A):c.2893C>T (p.Arg965Cys) which has been

reported as a disease causing mutation of BrS.17

18 19

The same variant has also been reported in patients with LQTS (with

digenic mutation in KCNH2 in one case).20

21 The allele frequency of this

variant (rs199473180) is reported to be 0.058% in East Asians (gnomAD). In

silico analyses by SIFT, MutationTaster, and PolyPhen-2 have revealed this

variant to be damaging, disease causing, and probably damaging,

respectively. Functional study showed that the p.(Arg965Cys) mutant led to

slower recovery from inactivation as a result of channels with a more

negative potential in steady state inactivation.18

Family screening found his father carrying the same SCN5A mutation

and a type 2 Brugada ECG pattern (Fig 1). However, no type 1 Brugada ECG feature was

revealed by a flecainide provocation test. The clinical phenotype in this

case supports the pathogenicity of this novel genetic variant.

Discussion

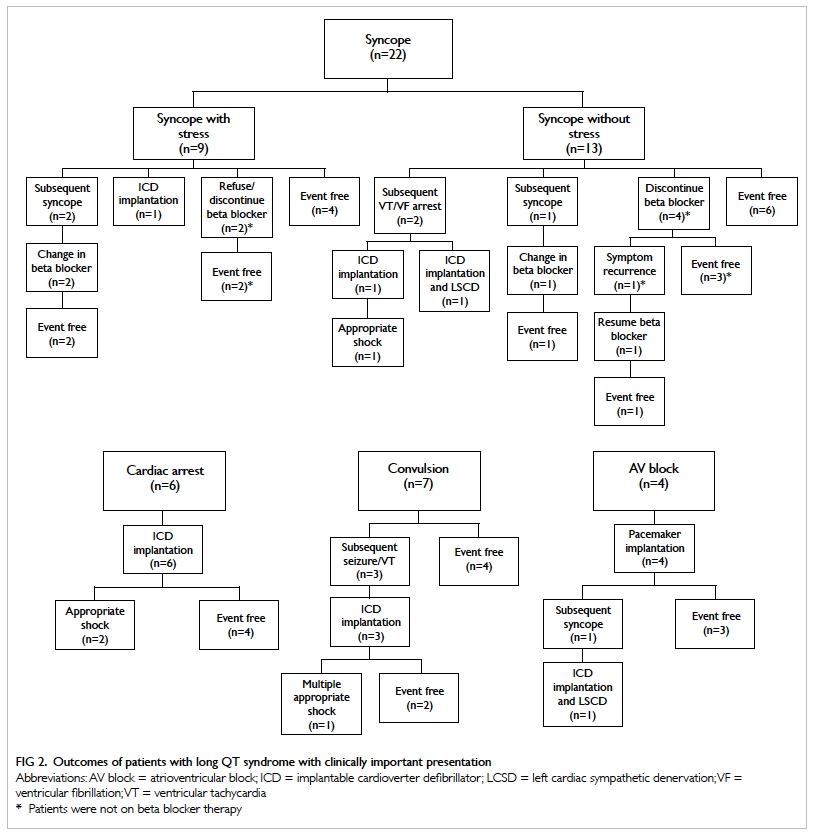

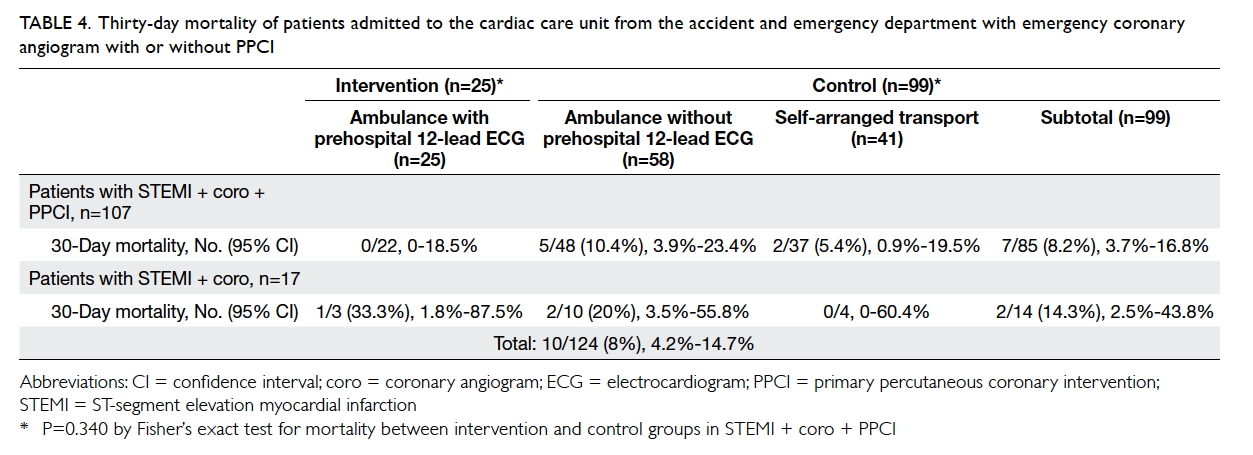

To elucidate the cause of SCD, a comprehensive

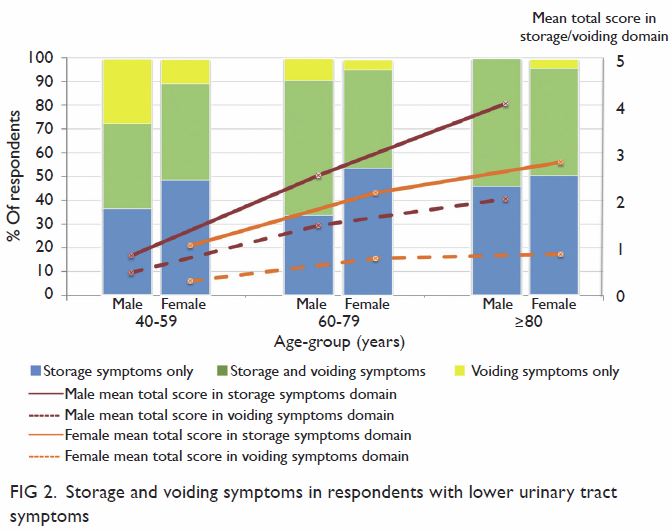

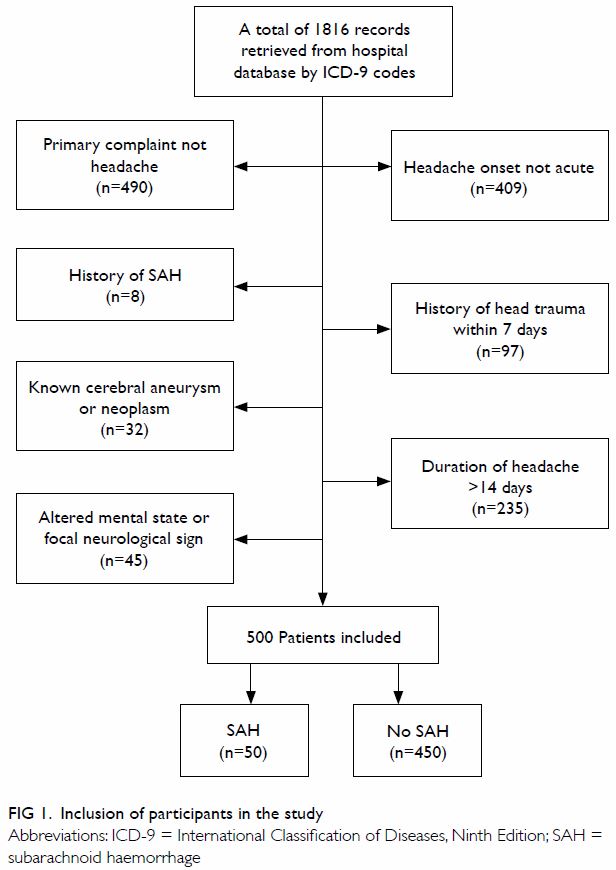

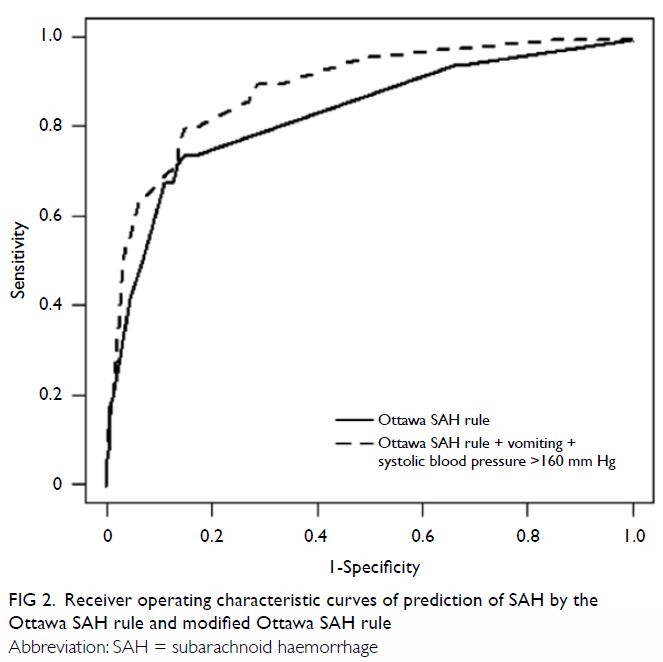

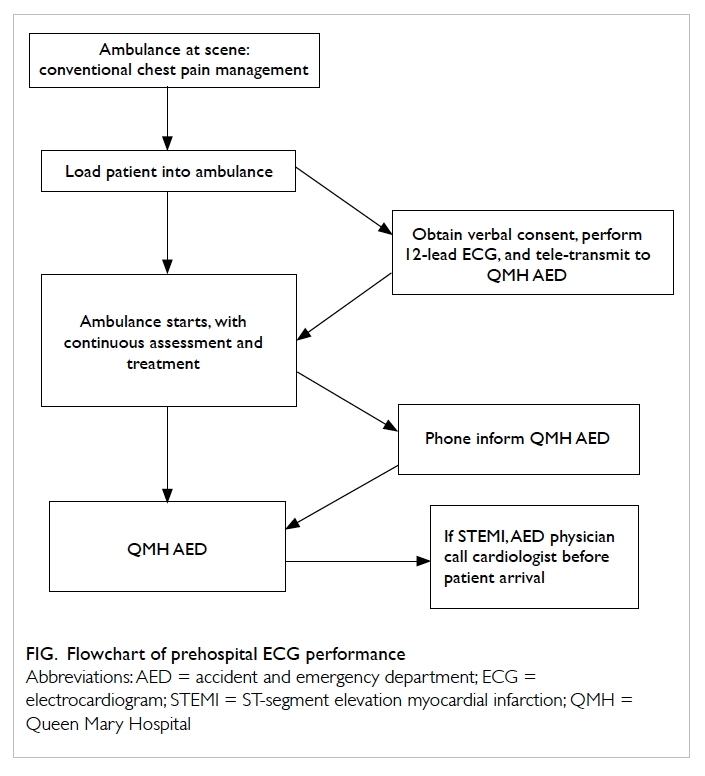

post-mortem evaluation is required. Figure 2 shows the combined approach using both

cardiac evaluation of surviving relatives and molecular autopsy on SUD

victims which would give a higher yield on elucidating the underlying

causes of SUD. Any history of syncope, cardiac symptoms especially related

to exertion, emotion and stress, previous ECG, circumstances of SCD

(activity at the time of death), any family history of cardiac disease,

premature or sudden death, near-arrest attack, and epilepsy should be

investigated. Patients with SADS can present with or be (incorrectly)

labelled as having epilepsy.22 23 24

25 Guidelines on post-mortem

examination of SUD in the young have been published by the Royal College

of Pathologists of Australasia (https://www.rcpa.edu.au/getattachment/89884c69-f066-411d-a3d1-

39460444db13/Guidelines-on-Autopsy-Practice.aspx). In addition to

traditional autopsy, some reports have used whole-body computed tomography

and magnetic resonance imaging to identify structural heart abnormalities

such as ARVC and HCM.26 27 However, these imaging modalities were not used in

the present study.

Figure 2. Proposed model of combining molecular autopsy and clinical assessment with conventional forensic investigation

Technologies applied in molecular autopsy have

changed from Sanger sequencing targeting a few major SUD-related genes to

NGS targeting an expanded gene panel of up to 200 genes.28 The former approach achieved diagnostic yields of

around 15% to 20%.8 16 29 30 31 32 With increasing throughput capacities at more

affordable costs, the large gene panel or exome approach by NGS is

becoming more appealing in molecular autopsy. A proof-of-principle

exome-wide study was carried out among 50 SUD subjects, with likely

pathogenic variants identified in 32%.33

The diagnostic yield from various NGS studies, including our own, is up to

35%, despite the different lengths of gene lists.13

34 35

36 However, the spectrum of

diseases might be different and rarer causes might be identified, because

substantial clinical suspicion is typically lacking among young SCD

victims with unremarkable premorbid history. However, a negative genetic

result does not necessarily exclude the possibility of a genetic basis for

the disease.

The major difficulty of molecular autopsy is

establishing the causation between the death and the genetic variants.

Applying molecular autopsy to the investigation of death causes involves

probabilistic rather than binary “yes or no” answers. Interpretation of

variant pathogenicity relies heavily on the characteristics of the genetic

variant, allele rarity in population frequencies, in silico predictions,

co-segregation patterns among affected family members, previous literature

data on reports of similar cases, and available functional data. This

approach follows the usual practice by which pathologists deal with

genetic reporting.

There are two main advantages of molecular autopsy

in SCD. First, molecular autopsy enables a correct diagnosis of SCD to be

established, which can bring some level of closure to the family. Findings

of a SADS-related condition can differentiate a natural cause from an

unnatural cause of death, such as the possibility of drowning precipitated

by an inherited arrhythmia during swimming. Second, the ultimate goal of

diagnosing SCD is to prevent another tragedy among family members. The

majority of SADS-related disorders are autosomal dominant inherited, and

family members are at 50% risk of inheriting the mutation, with variable

penetrance. Family pedigree for at least three generations should be

included in the extended clinical workup, and genetic counselling should

be considered for second- or higher-degree relatives wherever appropriate.

There are limitations to our study. First, SCD

victims with autopsy conducted in a public hospital were not recruited in

this study. Hence, the sample numbers may not be representative for the

whole territory. Second, no premorbid ECG findings of the victims were

available to correlate with the genetic results. Third, despite multiple

efforts, no genetic mutations were found in over two thirds of the SCD

victims in our study. Expanding the gene list may be able to increase the

yield. The associated phenotypes and pathogenesis of some genes are still

yet to be further elucidated.

Conclusion

Sudden arrhythmia death syndrome is a significant

cause of SCD in the young. This study is first of its kind in an East

Asian population and provides important data on the prevalence and types

of SADS among young SCD victims. This is also the first local feasibility

study on incorporating cardiac evaluation of surviving relatives and NGS

molecular autopsy into the conventional forensic investigations. The

interpretation of genetic variants in the context of SCD is complicated

and we recommend its analysis and reporting by qualified pathologists.

This model may be considered to cover all age-groups of SCD victims, as

well as other potential applications such as sudden unexpected death in

epilepsy, or sudden infant death syndrome. This local pilot study should

be considered an important advance in diagnosing young SCD victims in East

Asian populations.

Author contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to

the concept or design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis or

interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision

for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the

data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for

publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of

interest.

Declaration

The 5-year review was presented at the Asia Pacific

Heart Rhythm Society Meeting on 3 to 6 October 2013, in Hong Kong. Part of

the SADS HK Study results was presented at CardioRhythm on 24 to 26

February 2017, in Hong Kong and was published (J HK Coll Cardiol

2016;24:34).

Funding/support

This work was partly funded by SADS HK Foundation

Limited, Hong Kong.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by local ethics committees

(Ethic Committee of the Department of Health (L/M 601/2013) and Kowloon

West Cluster Research Ethics Committee (KWC-REC Reference

KW/FR-13-023-67-05)). Consent was obtained from the next-of-kin of the SCD

victims and from the first-degree relatives themselves under study.

References

1. Puranik R, Chow CK, Duflou JA, Kilborn

MJ, McGuire MA. Sudden death in the young. Heart Rhythm 2005;2:1277-82. Crossref

2. Chugh SS, Reinier K, Teodorescu C, et

al. Epidemiology of sudden cardiac death: clinical and research

implications. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2008;51:213-28. Crossref

3. Basso C, Corrado D, Thiene G.

Cardiovascular causes of sudden death in young individuals including

athletes. Cardiol Rev 1999;7:127-35. Crossref

4. Link MS. Sudden cardiac death in the

young: epidemiology and overview. Congenit Heart Dis 2017;12:597-9. Crossref

5. Chugh SS, Kelly KL, Titus JL. Sudden

cardiac death with apparently normal heart. Circulation 2000;102:649-54. Crossref

6. Corrado D, Basso C, Thiene G. Sudden

cardiac death in young people with apparently normal heart. Cardiovasc Res

2001;50:399-408. Crossref

7. de Noronha SV, Sharma S, Papadakis M,

Desai S, Whyte G, Sheppard MN. Aetiology of sudden cardiac death in

athletes in the United Kingdom: a pathological study. Heart

2009;95:1409-14. Crossref

8. Tester DJ, Medeiros-Domingo A, Will ML,

Haglund CM, Ackerman MJ. Cardiac channel molecular autopsy: insights from

173 consecutive cases of autopsy-negative sudden unexplained death

referred for postmortem genetic testing. Mayo Clin Proc 2012;87:524-39. Crossref

9. Ackerman MJ, Tester DJ, Driscoll DJ.

Molecular autopsy of sudden unexplained death in the young. Am J Forensic

Med Pathol 2001;22:105-11. Crossref

10. Tester DJ, Ackerman MJ. The role of

molecular autopsy in unexplained sudden cardiac death. Curr Opin Cardiol

2006;21:166-72. Crossref

11. Wever-Pinzon OE, Myerson M, Sherrid

MV. Sudden cardiac death in young competitive athletes due to genetic

cardiac abnormalities. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg 2009;9 Suppl 2:17-23.

12. Hellenthal N, Gaertner-Rommel A,

Klauke B, et al. Molecular autopsy of sudden unexplained deaths reveals

genetic predispositions for cardiac diseases among young forensic cases.

Europace 2017;19:1881-90. Crossref

13. Hertz CL, Christiansen SL,

Ferrero-Miliani L, et al. Next-generation sequencing of 100 candidate genes

in young victims of suspected sudden cardiac death with structural

abnormalities of the heart. Int J Legal Med 2016;130:91-102. Crossref

14. Christiansen SL, Hertz CL,

Ferrero-Miliani L, et al. Genetic investigation of 100 heart genes in

sudden unexplained death victims in a forensic setting. Eur J Hum Genet

2016;24:1797-802. Crossref

15. Semsarian C, Hamilton RM. Key role of

the molecular autopsy in sudden unexpected death. Heart Rhythm

2012;9:145-50. Crossref

16. Tester DJ, Spoon DB, Valdivia HH,

Makielski JC, Ackerman MJ. Targeted mutational analysis of the

RyR2-encoded cardiac ryanodine receptor in sudden unexplained death: a

molecular autopsy of 49 medical examiner/coroner’s cases. Mayo Clin Proc

2004;79:1380-4. Crossref

17. Priori SG, Napolitano C, Gasparini M,

et al. Natural history of Brugada syndrome: insights for risk

stratification and management. Circulation 2002;105:1342-7. Crossref

18. Hsueh CH, Chen WP, Lin JL, et al.

Distinct functional defect of three novel Brugada syndrome related cardiac

sodium channel mutations. J Biomed Sci 2009;16:23. Crossref

19. Yu JH, Hu JZ, Zhou H, et al. SCN5A

mutation in patients with Brugada electrocardiographic pattern induced by

fever [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi 2013;41:1010-4.

20. Jimmy JJ, Chen CY, Yeh HM, et al.

Clinical characteristics of patients with congenital long QT syndrome and

bigenic mutations. Chin Med J (Engl) 2014;127:1482-6.

21. Lieve KV, Williams L, Daly A, et al.

Results of genetic testing in 855 consecutive unrelated patients referred

for long QT syndrome in a clinical laboratory. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers

2013;17:553-61. Crossref

22. Medford BA, Bos JM, Ackerman MJ.

Epilepsy misdiagnosed as long QT syndrome: it can go both ways. Congenit

Heart Dis 2014;9:E135-9. Crossref

23. Partemi S, Cestèle S, Pezzella M, et

al. Loss-of-function KCNH2 mutation in a family with long QT

syndrome, epilepsy, and sudden death. Epilepsia 2013;54:e112-6. Crossref

24. Goyal JP, Sethi A, Shah VB. Jervell

and Lange-Nielson Syndrome masquerading as intractable epilepsy. Ann

Indian Acad Neurol 2012;15:145-7. Crossref

25. Tu E, Bagnall RD, Duflou J, Semsarian

C. Post-mortem review and genetic analysis of sudden unexpected death in

epilepsy (SUDEP) cases. Brain Pathol 2011;21:201-8. Crossref

26. Roberts IS, Benamore RE, Benbow EW, et

al. Post-mortem imaging as an alternative to autopsy in the diagnosis of

adult deaths: a validation study. Lancet 2012;379:136-42. Crossref

27. Puranik R, Gray B, Lackey H, et al.

Comparison of conventional autopsy and magnetic resonance imaging in

determining the cause of sudden death in the young. J Cardiovasc Magn

Reson 2014;16:44. Crossref

28. Semsarian C, Ingles J. Molecular

autopsy in victims of inherited arrhythmias. J Arrhythm 2016;32:359-65. Crossref

29. Liu C, Zhao Q, Su T, et al. Postmortem

molecular analysis of KCNQ1, KCNH2, KCNE1 and KCNE2

genes in sudden unexplained nocturnal death syndrome in the Chinese Han

population. Forensic Sci Int 2013;231:82-7. Crossref

30. Doolan A, Langlois N, Chiu C, Ingles

J, Lind JM, Semsarian C. Postmortem molecular analysis of KCNQ1

and SCN5A genes in sudden unexplained death in young Australians.

Int J Cardiol 2008;127:138-41. Crossref

31. Skinner JR, Crawford J, Smith W, et

al. Prospective, population-based long QT molecular autopsy study of

postmortem negative sudden death in 1 to 40 year olds. Heart Rhythm

2011;8:412-9. Crossref

32. Hofman N, Tan HL, Alders M, et al.

Yield of molecular and clinical testing for arrhythmia syndromes: report

of 15 years’ experience. Circulation 2013;128:1513-21. Crossref

33. Bagnall RD, Das K J, Duflou J,

Semsarian C. Exome analysis-based molecular autopsy in cases of sudden

unexplained death in the young. Heart Rhythm 2014;11:655-62. Crossref

34. Bagnall RD, Weintraub RG, Ingles J, et

al. A prospective study of sudden cardiac death among children and young

adults. N Engl J Med 2016;374:2441-52. Crossref

35. Farrugia A, Keyser C, Hollard C, Raul

JS, Muller J, Ludes B. Targeted next generation sequencing application in

cardiac channelopathies: analysis of a cohort of autopsy-negative sudden

unexplained deaths. Forensic Sci Int 2015;254:5-11. Crossref

36. Tester DJ, Ackerman MJ. Postmortem

long QT syndrome genetic testing for sudden unexplained death in the

young. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:240-6. Crossref