Prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities and 22q11.2 deletion in conotruncal and non-conotruncal antenatally diagnosed congenital heart diseases in a Chinese population

Hong

Kong Med J 2019 Feb;25(1):6–12 | Epub 18 Jan 2019

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities and 22q11.2

deletion in conotruncal and non-conotruncal antenatally diagnosed

congenital heart diseases in a Chinese population

CW Kong, MB, ChB, MRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and

Gynaecology)1; Yvonne KY Cheng, MB, ChB, MRCOG, FHKAM

(Obstetrics and Gynaecology)2; William WK To, FRCOG, MD1;

TY Leung, FRCOG, MD2

1 Department of Obstetrics and

Gynaecology, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

2 Department of Obstetrics and

Gynaecology, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr CW Kong (melizakong@gmail.com)

Abstract

Introduction: The aim of the

present study was to calculate the prevalence of chromosomal

abnormalities among antenatally diagnosed congenital heart diseases

(CHDs), and the prevalence of 22q11.2 deletion in those with conotruncal

CHDs versus isolated non-conotruncal CHDs.

Methods: All patients with

antenatal ultrasound finding of fetal CHDs in two obstetric units in a

5-year period were retrospectively reviewed. Detected CHDs were

classified as conotruncal if the malformation involved either the aortic

outflow tract or the pulmonary outflow tract; otherwise they were

classified as non-conotruncal. Karyotyping, fluorescence in situ

hybridisation for 22q11.2 deletion (22q11FISH), and array comparative

genomic hybridisation (aCGH) results were retrieved from patient medical

records. The primary outcome was prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities

in CHDs. The secondary outcomes were prevalence of 22q11.2 deletion and

its prevalence in conotruncal versus non-conotruncal CHDs.

Results: A total of 254 Chinese

patients were diagnosed to have fetal CHDs. In all, 50 (19.7%) were

found to have chromosomal abnormalities with seven (2.8%) patients

having 22q11.2 deletion, of whom all seven had conotruncal CHDs and none

had non-conotruncal CHDs (P<0.05). Conventional karyotyping detected

35 (70%) cases of the chromosomal abnormalities. The 22q11FISH detected

three cases of 22q11.2 deletion; aCGH was performed to detect four cases

of 22q11.2 deletion and eight other cases of copy number variations.

Conclusion: Our results suggest

that invasive testing for karyotyping is recommended for fetal CHDs.

Although the prevalence of 22q11.2 deletion was low, testing for 22q11.2

deletion should be offered for conotruncal CHDs.

New knowledge added by this study

- Prevalence of 22q11.2 deletion in the Chinese population is low.

- Cardiac abnormalities in 22q11.2 deletion are mainly conotruncal cardiac defects.

- Patients should receive counselling for invasive testing for chromosomal abnormalities in fetal cardiac lesions.

- Testing for 22q11.2 deletion is recommended for conotruncal cardiac defect.

Introduction

Congenital heart diseases (CHDs) are the commonest

congenital malformations at birth and a leading cause of neonatal

mortality, with an incidence of around eight in 1000 births.1 The reported incidence of chromosomal abnormalities in

patients with CHDs differs between infants and fetuses, as well as among

different series and studies, ranging from 9% to 18%.2 3 4 5 6 7 Many previous

studies have typically only included major aneuploidies as chromosomal

abnormalities; other chromosomal aberrations, such as 22q11.2 deletion or

other microdeletions, were not investigated. The availability of new

cytogenetic and molecular technologies, such as specific fluorescence in

situ hybridisation (FISH) probes, array comparative genomic hybridisation

(aCGH),8 or sophisticated genome

sequencing methods,9 10 has increased the identified contribution of

chromosomal abnormalities.

The frequency of 22q11.2 deletions among all cases

of CHDs has been estimated to be around 2% to 5.7%.11 The prevalence of 22q11.2 deletions in the Chinese

population has not been well documented. However, recent studies have

shown that the condition is likely to be underdiagnosed in adult Chinese

populations, as recognition of clinical and dysmorphic features could be

unreliable.12 The most frequently

encountered CHDs in this syndrome are conotruncal CHDs that involve the

pulmonary or aortic outflow tracts. However, 22q11.2 deletions are also

associated with isolated non-conotruncal CHDs.13

14

The objective of this study was to calculate the

prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities among antenatally diagnosed CHDs,

and the prevalence of 22q11.2 deletion in those with conotruncal CHDs

versus isolated non-conotruncal CHDs.

Methods

All pregnant patients with antenatal ultrasound

finding of fetal CHDs from July 2012 to June 2017 in two maternal fetal

medicine referral centres, United Christian Hospital and Prince of Wales

Hospital, Hong Kong, were retrospectively retrieved from the obstetric

ultrasound database. Non-Chinese patients were excluded from this cohort.

The detected CHDs were classified as conotruncal if the malformation

involved either the aortic outflow tract or the pulmonary outflow tract;

otherwise, they were classified as non-conotruncal. According to the

protocol of these two hospitals, pregnant patients with antenatal

ultrasound findings of CHDs were offered invasive testing for karyotyping.

Self-financed aCGH was recommended to the patient; if she declined aCGH,

FISH for 22q11.2 deletion (22q11FISH) was offered free of charge. The

aCGH, FISH, and karyotype of patients from United Christian Hospital were

sent to the prenatal diagnostic laboratory of Tsan Yuk Hospital; those of

patients from Prince of Wales Hospital were sent to the prenatal

diagnostic laboratory of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. NimbleGen

CGX 135k (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and CGX v2 60k (PerkinElmer, Waltham

[MA], US) oligonucleotide arrays were used in the aCGH studies in the Tsan

Yuk Hospital from July 2012 to March 2014 and from March 2014 to June

2017, respectively. Copy number variations (CNVs) were categorised as

previously reported by Kan et al.15

A customised 44k Fetal Chip v1.0 and a 60k Fetal Chip v2.0 (Agilent

Technologies, Inc, Santa Clara [CA], US) were used in the Chinese

University of Hong Kong for the aCGH studies from July 2012 to November

2013 and from December 2013 to June 2017, respectively. The CNVs were

categorised as previously reported by Leung et al.16

The aCGH, 22q11FISH, and karyotyping results were

reviewed from patient medical records. The prevalence of chromosomal

abnormalities in these antenatally diagnosed CHDs fetuses, specifically

the prevalence of 22q11.2 deletion, was calculated and compared between

the conotruncal CHDs and the non-conotruncal CHDs. The primary outcome was

the prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities in CHDs. The secondary

outcomes were the total prevalence of 22q11.2 deletion in conotruncal CHDs

compared with that in non-conotruncal CHDs.

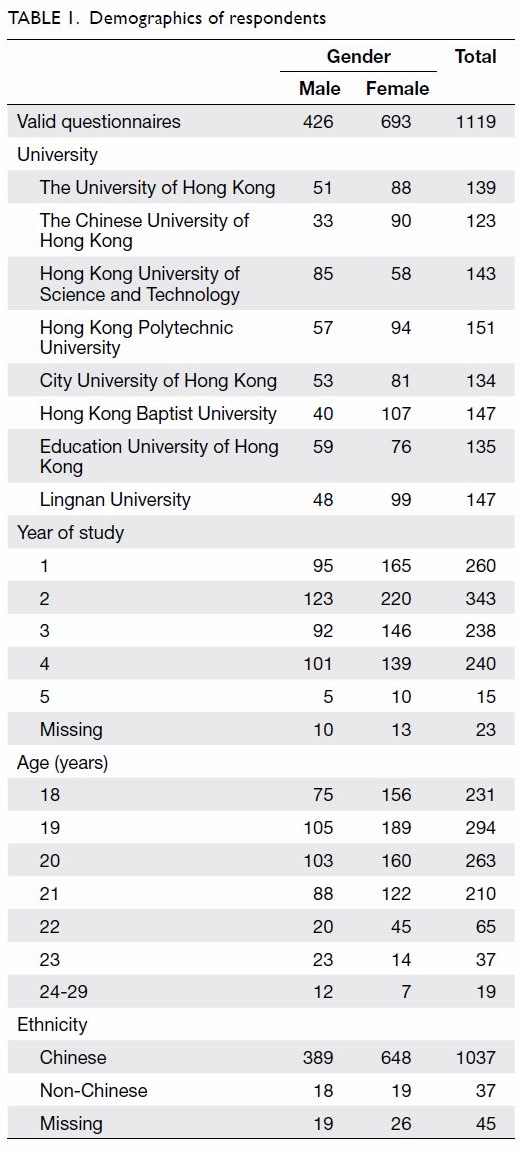

The SPSS (Windows version 20.0; IBM Corp, Armonk

[NY], US) was used for data entry and analysis. Comparison of categorical

variables between the conotruncal and non-conotruncal groups was analysed

by Chi squared test or Fisher exact test where appropriate. A P value of

<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational

Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement was used in the preparation of

this article.17

Results

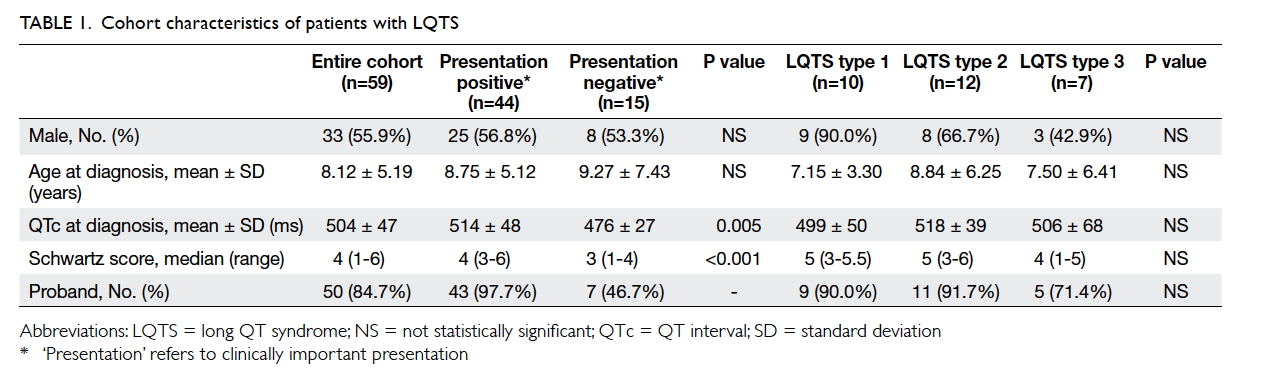

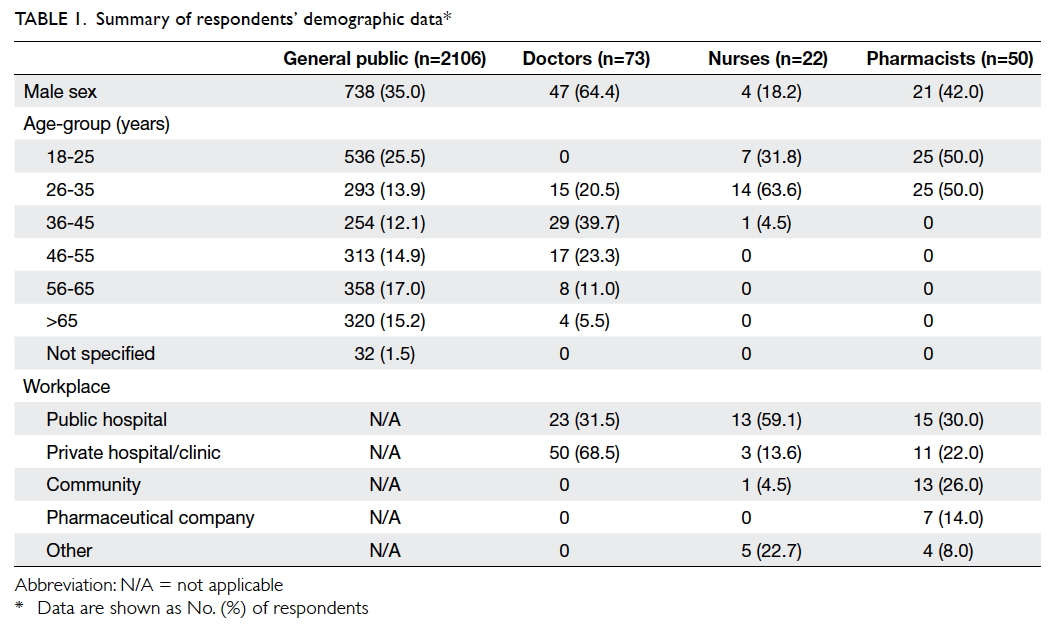

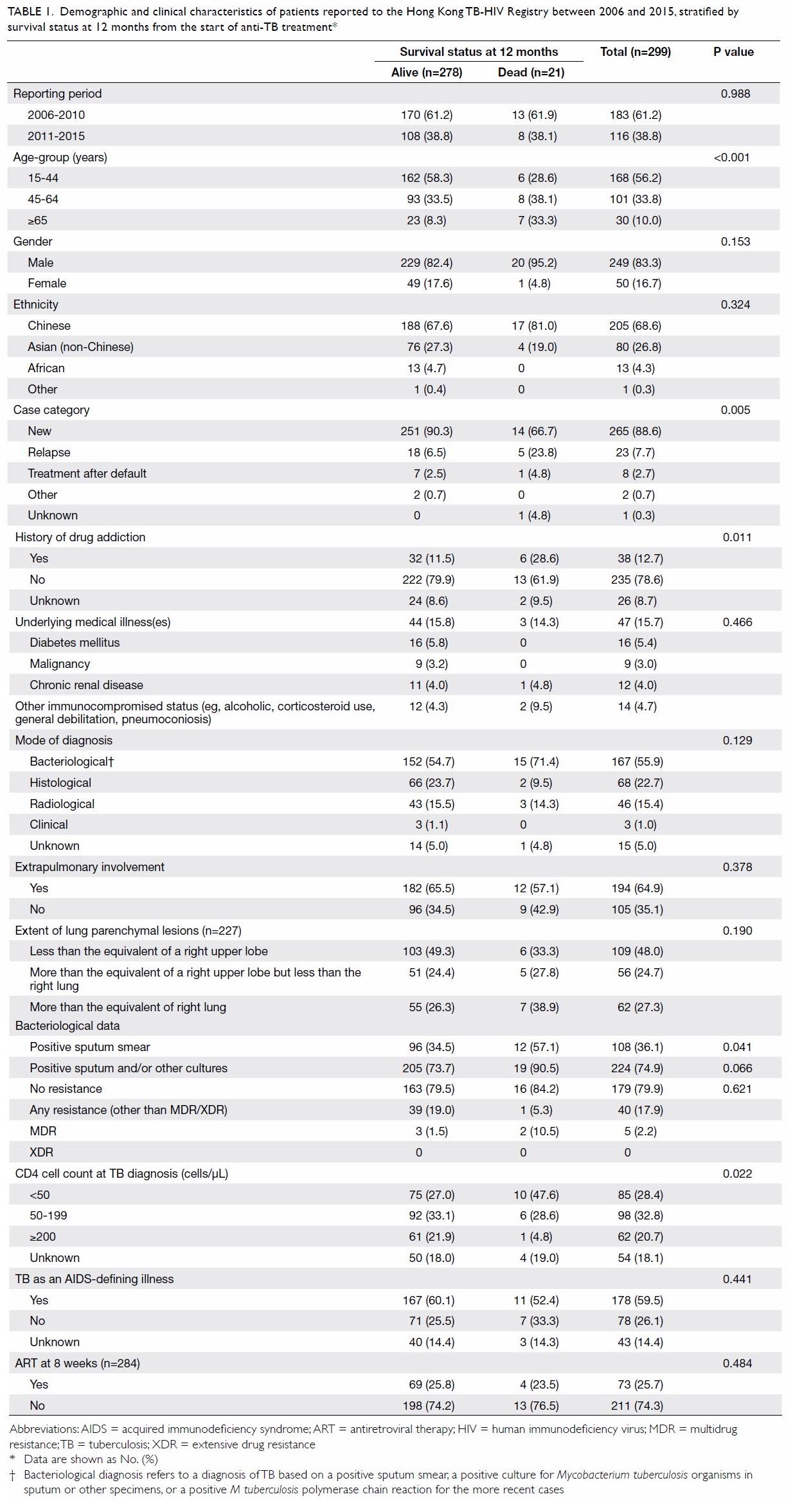

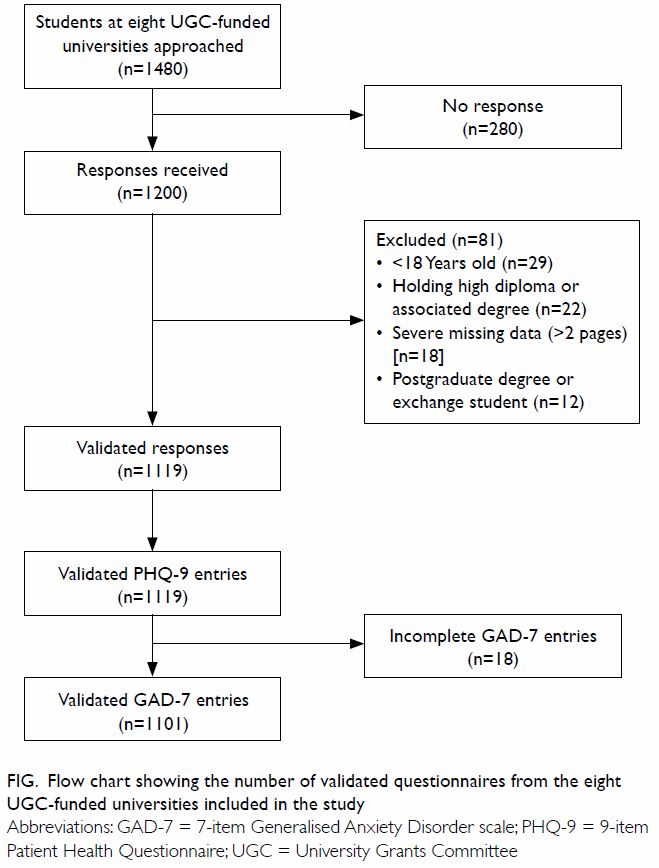

From July 2012 to June 2017, there were 54 802

deliveries in United Christian Hospital and Prince of Wales Hospital,

among which 264 (0.48%) patients were diagnosed to have fetal CHDs by

antenatal ultrasound scan. Of these, 254 (96.2%) patients were Chinese and

were recruited for final analysis. The mean (± standard deviation)

maternal age was 32.3 ± 4.9 years, with 151 (59.4%) patients being

nulliparous. The mean gestational age at diagnosis of fetal CHDs by

ultrasound was 20.4 ± 2.9 weeks. Within the total cohort of 254 patients

with fetal CHDs, 160 (63.0%) were classified into the conotruncal group,

while 94 (37.0%) were classified into the non-conotruncal group. The

prevalence of the various types of conotruncal and non-conotruncal CHDs

and the prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities are listed in Table

1. Fourty-one (16.1%) patients had other structural abnormalities

found in antenatal ultrasound apart from CHDs.

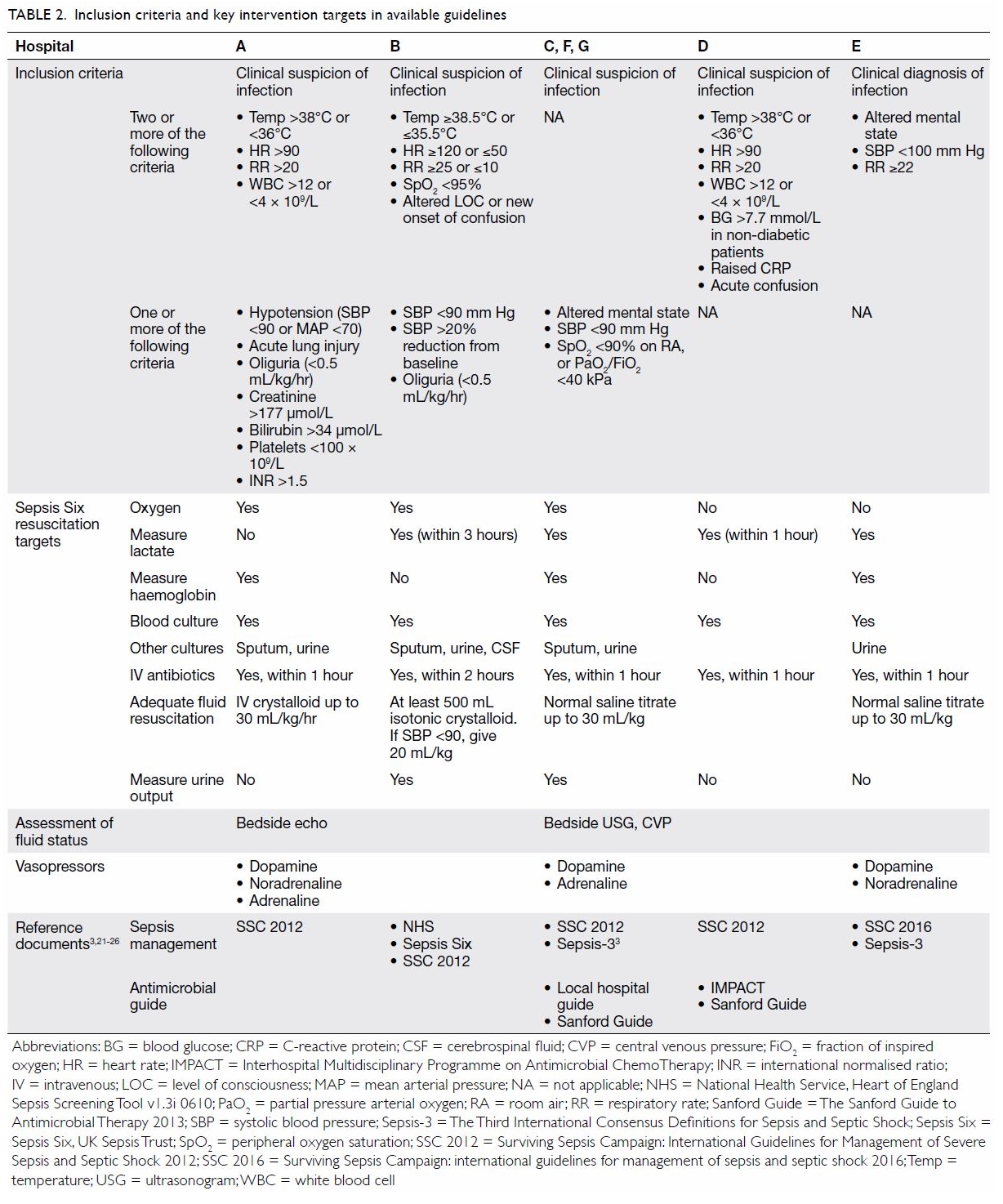

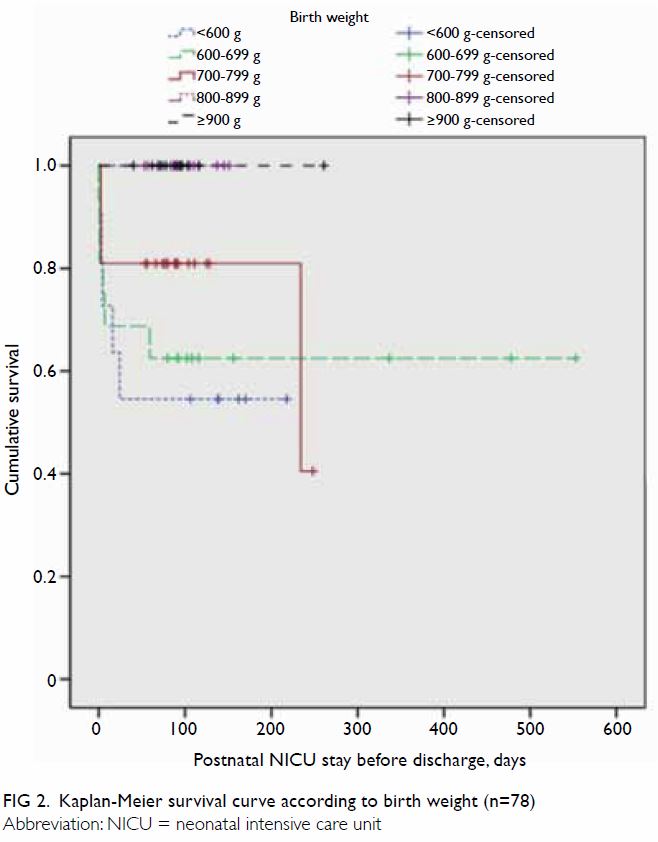

Table 1. Prevalence of conotruncal and non-conotruncal defects and associated chromosomal abnormalities

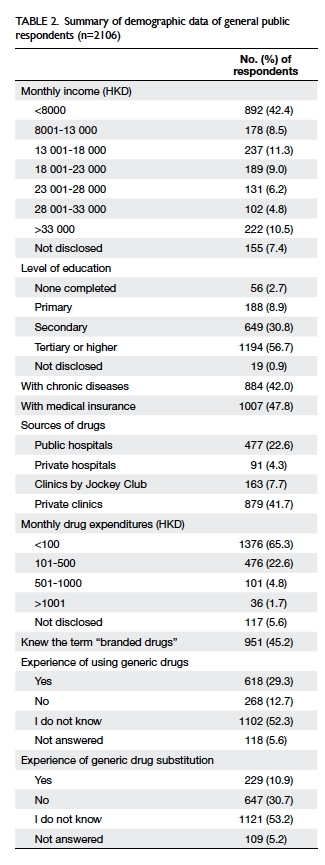

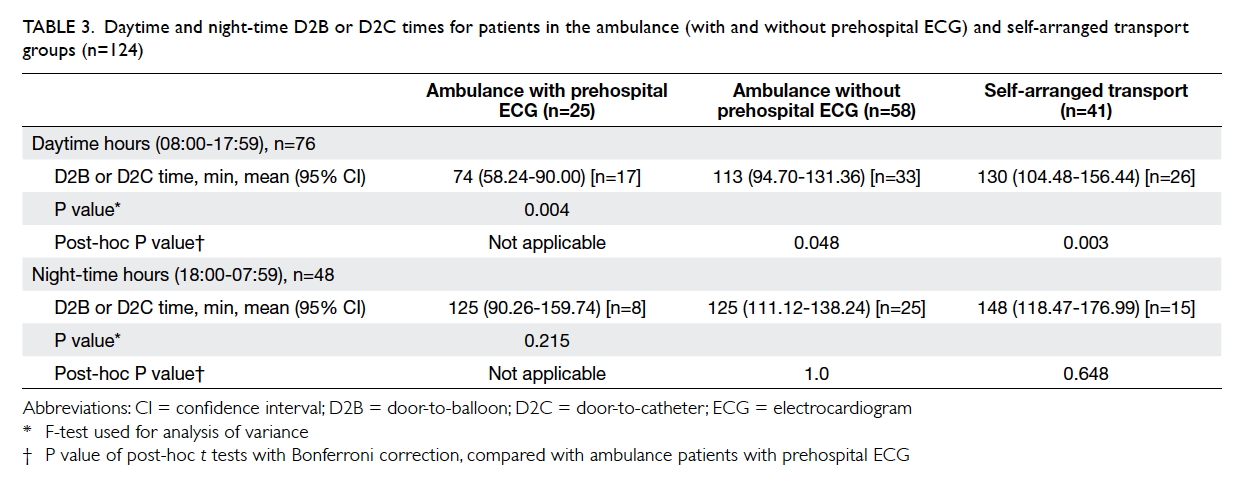

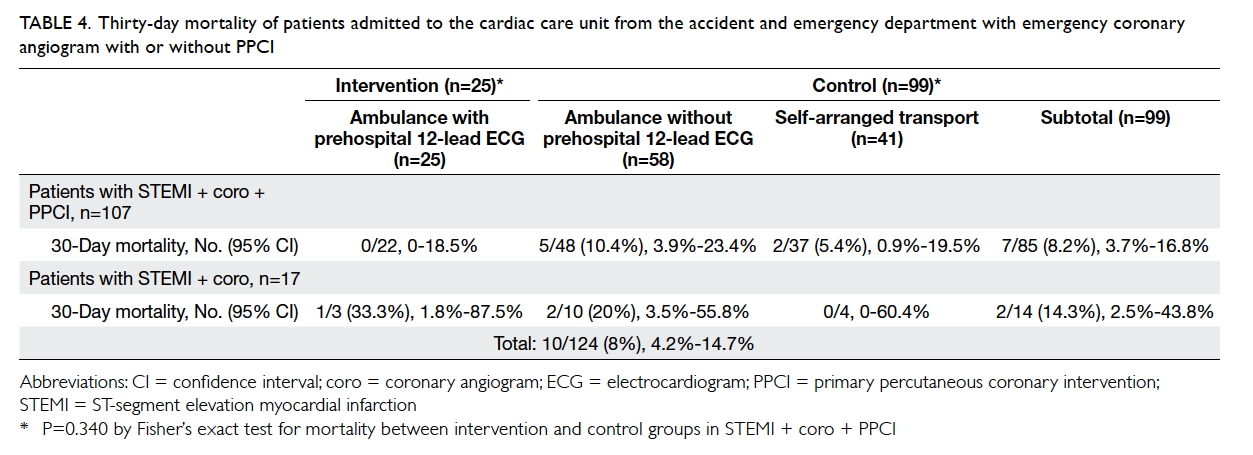

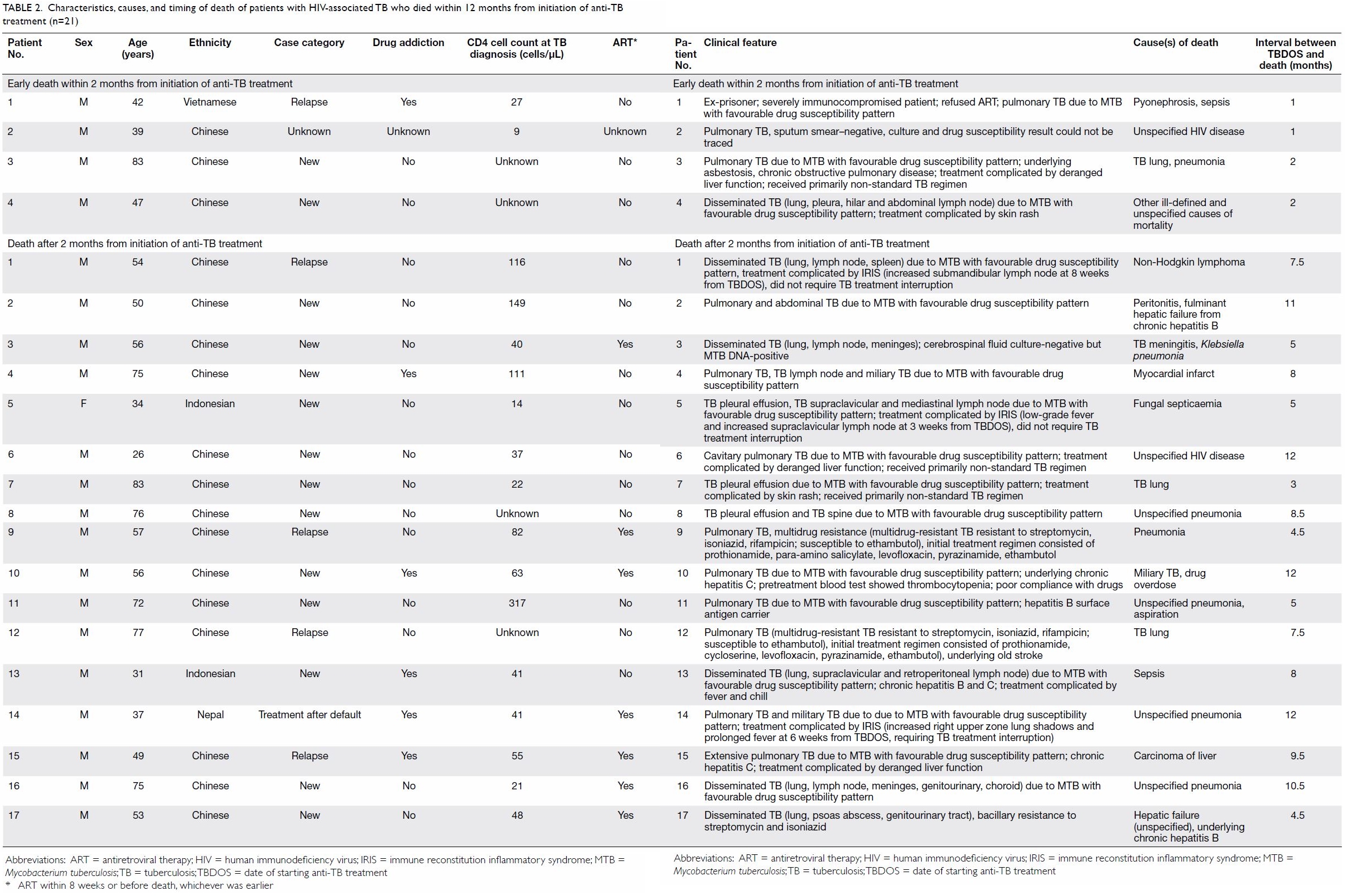

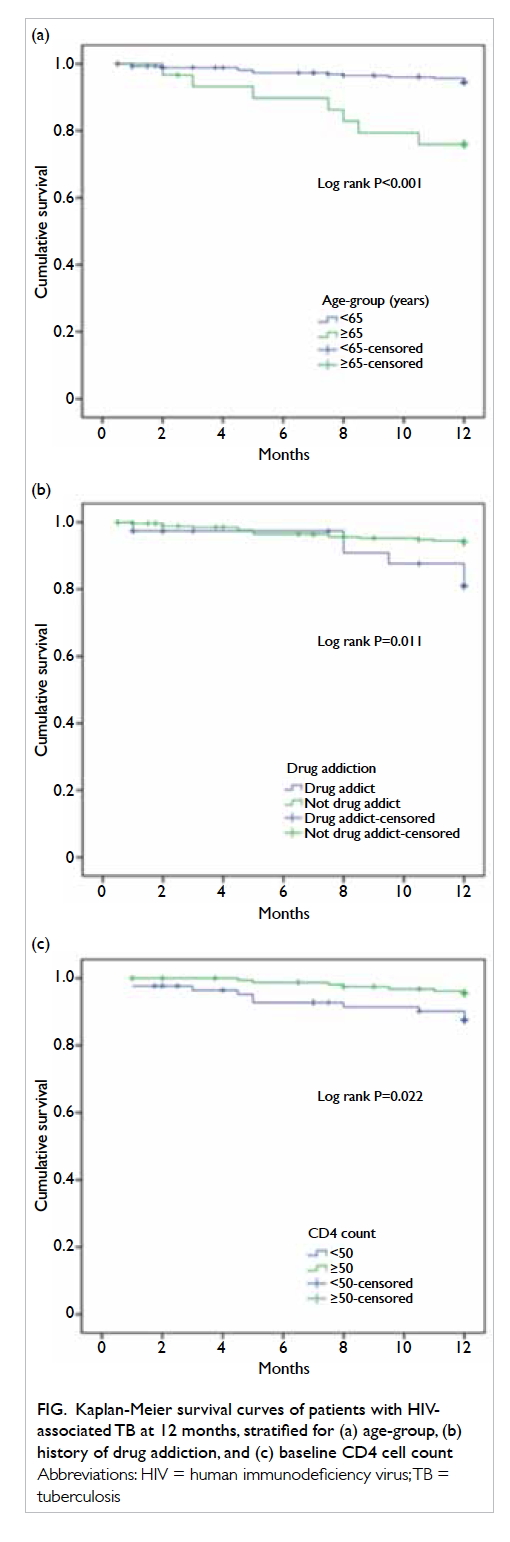

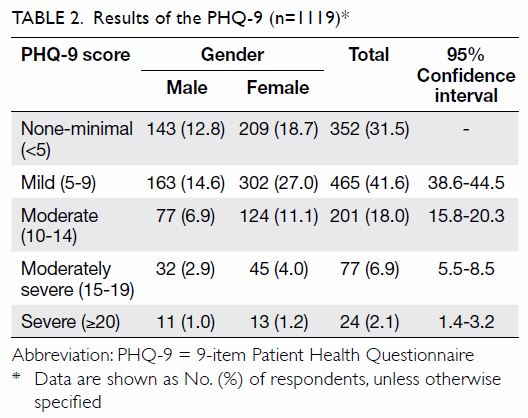

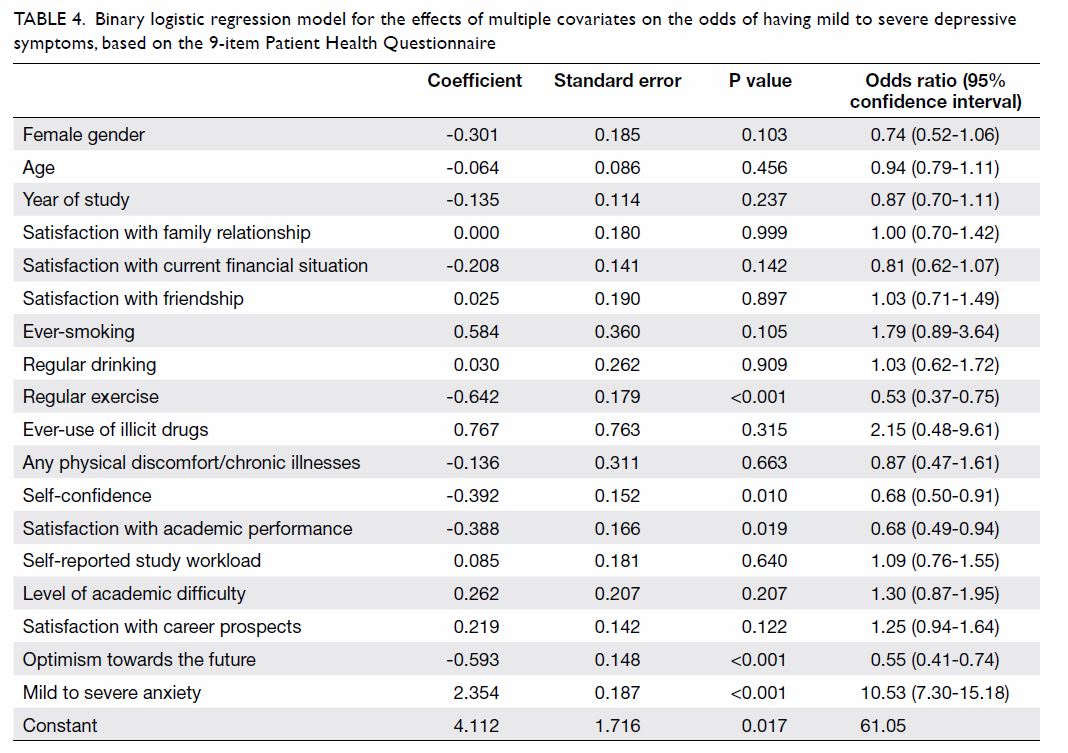

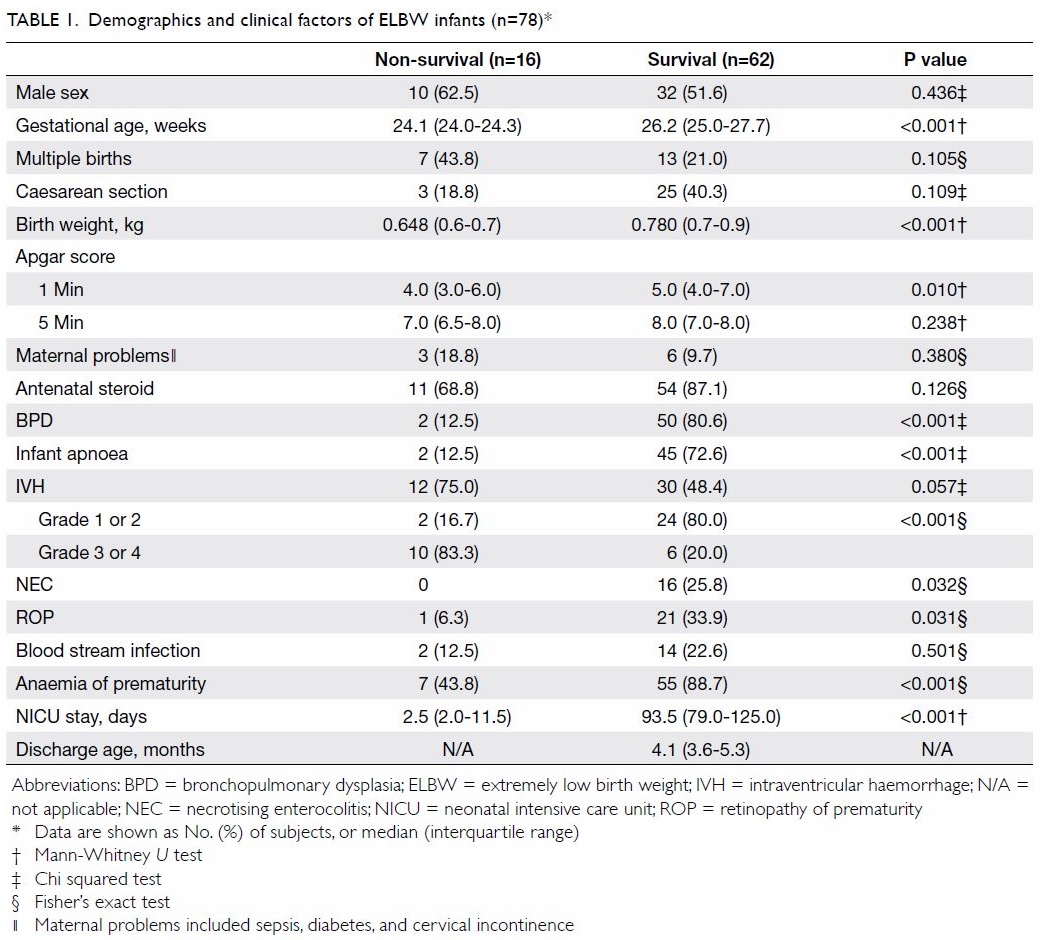

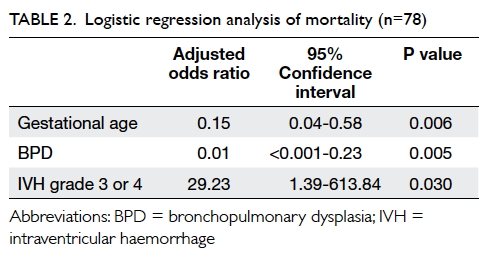

Chromosomal analysis and karyotyping was done in

207 (81.5%) patients; of them, aCGH was performed in 146 (70.5%) and

22q11FISH was performed in 61 (29.5%). The remaining 47 patients refused

chromosomal analysis. In the group of 207 fetuses with karyotype

performed, 50 (24.2%) were found to have chromosomal abnormalities;

trisomy 21 and trisomy 18 accounted for 42.0% of all these abnormalities.

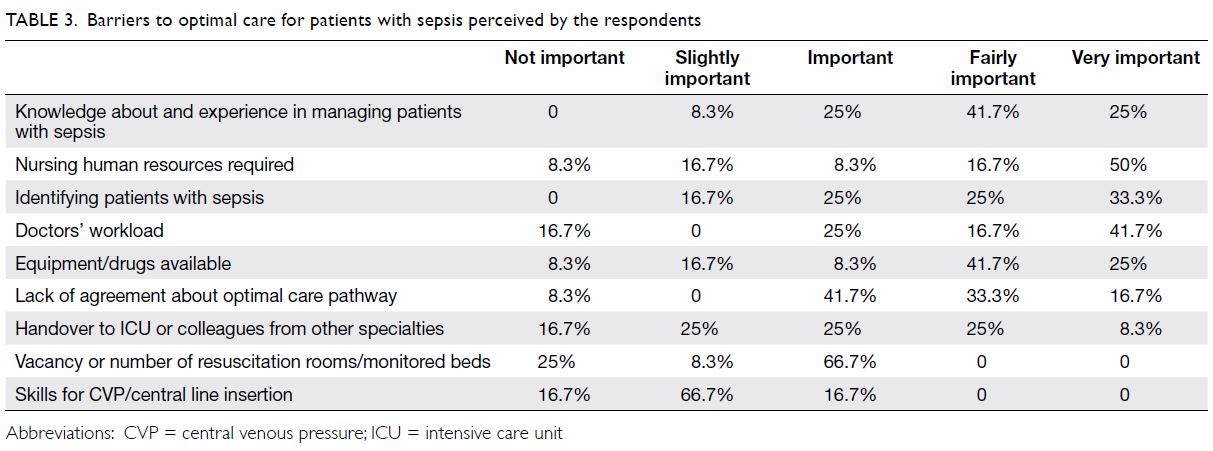

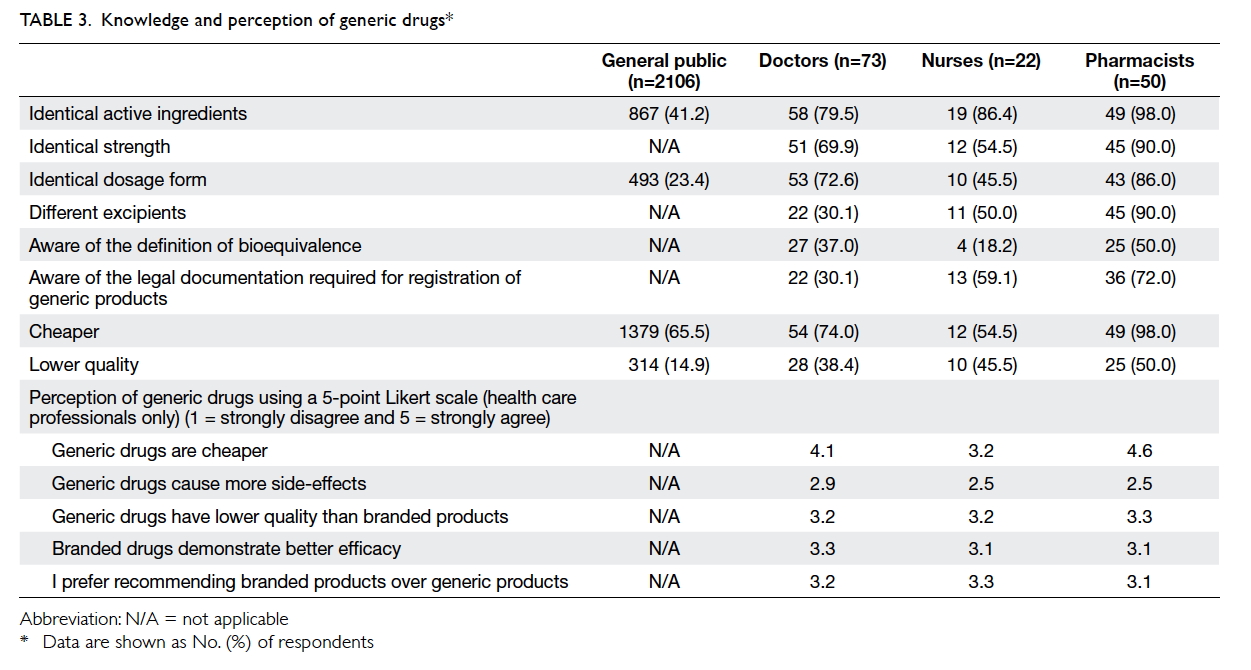

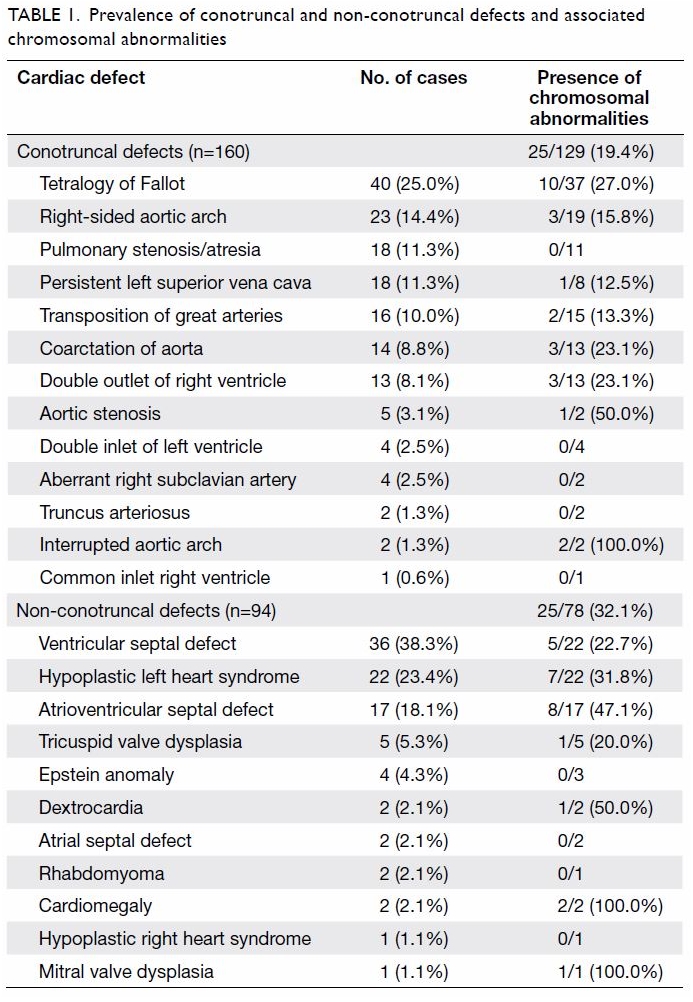

The different types of chromosomal abnormalities are shown in Table

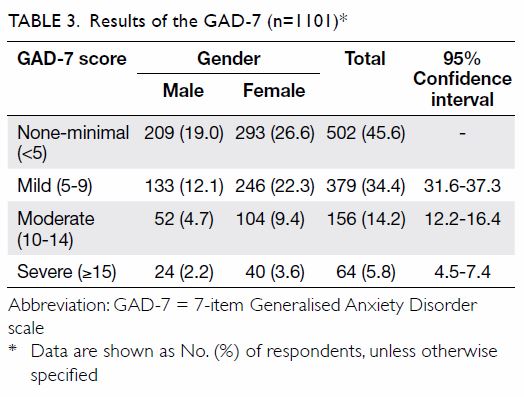

2. Of the 50 cases with chromosomal abnormalities, 35 (70%) were

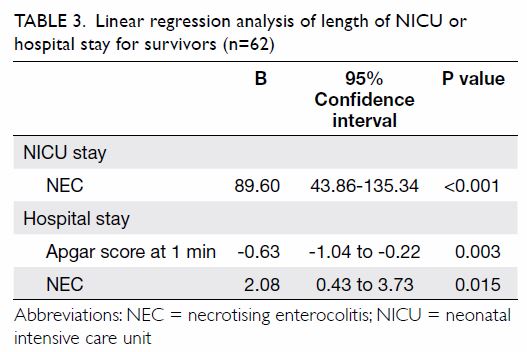

detected by conventional karyotyping. Three cases of 22q11.2 deletion were

detected by FISH; aCGH detected another four cases of 22q11.2 deletion and

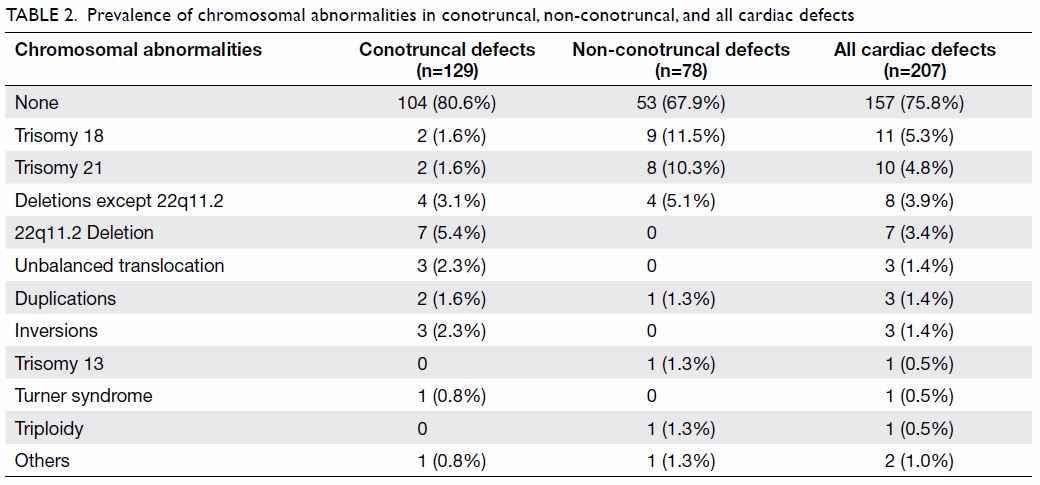

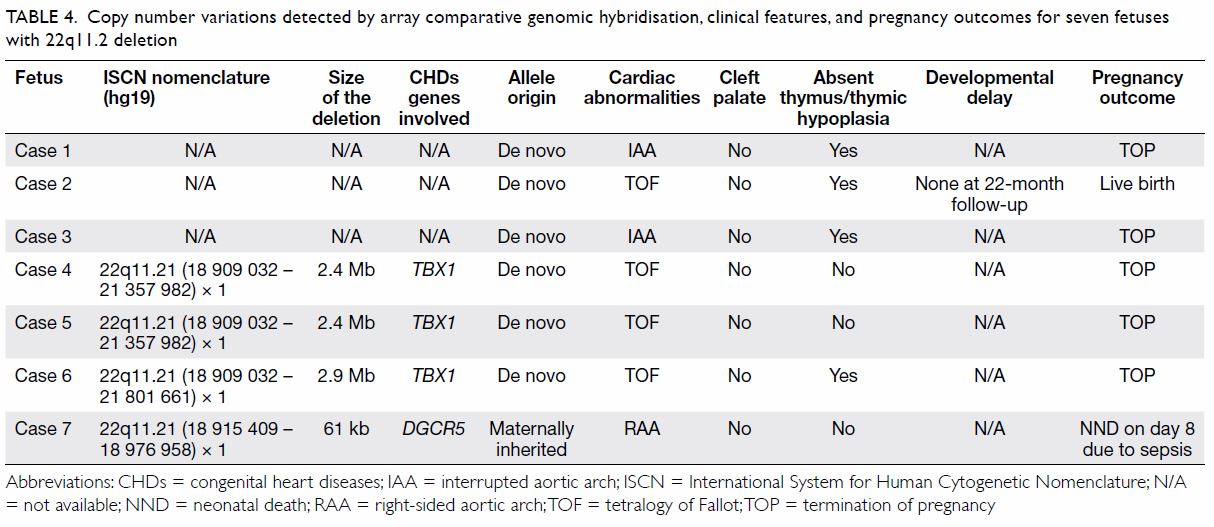

eight cases of other CNVs, as shown in Table 3. The prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities

in fetuses without extracardiac abnormalities was 29 of 168 (17.3%),

whereas that in fetuses with extracardiac abnormalities was 21 of 39

(53.8%). The prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities in non-conotruncal

CHDs was 25 of 78 (32.1%) which was significantly higher than that in

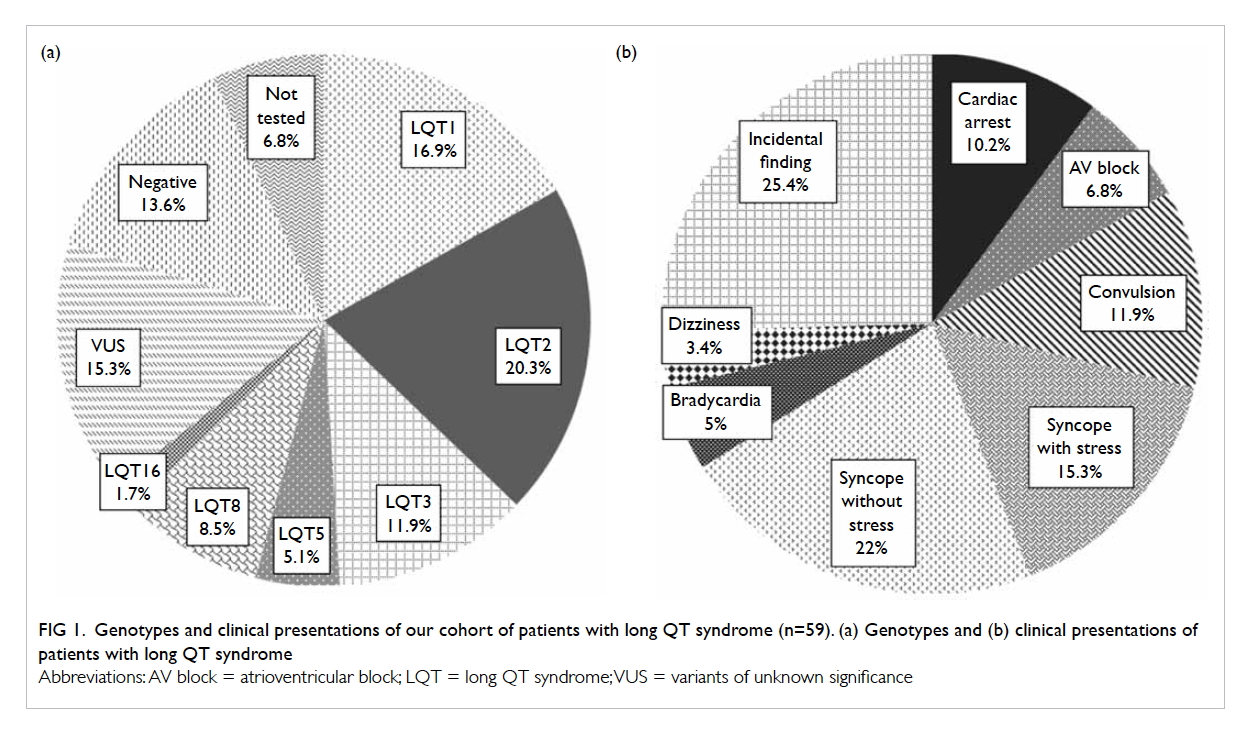

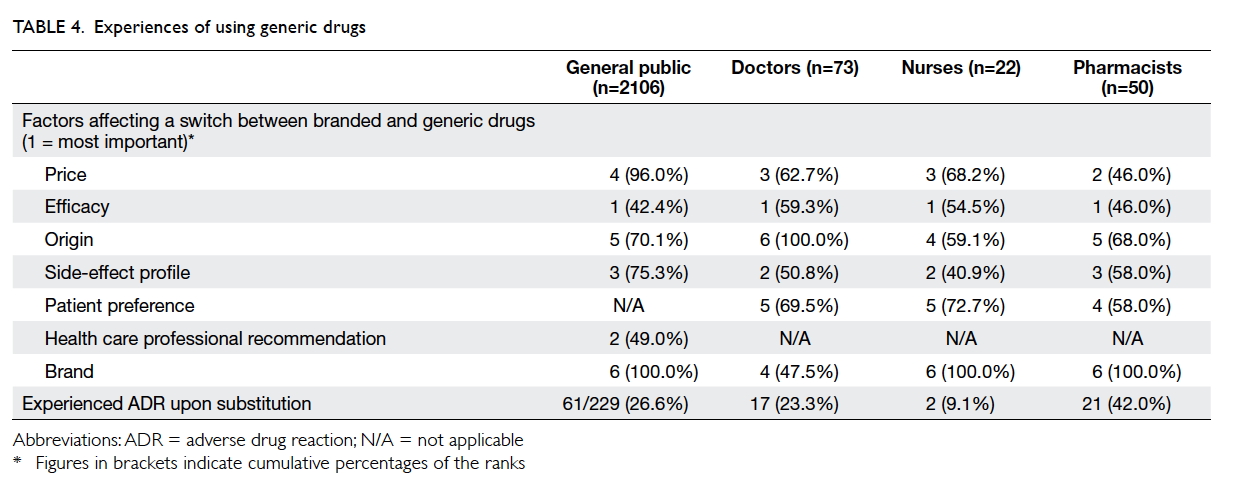

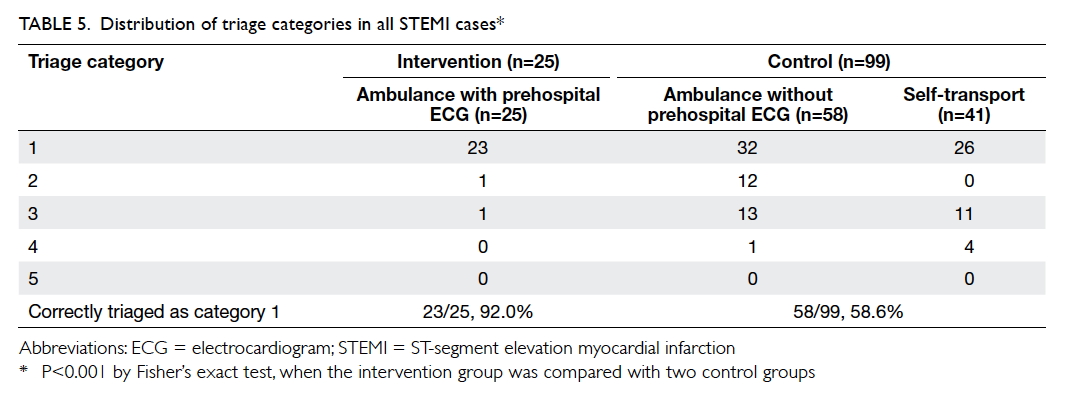

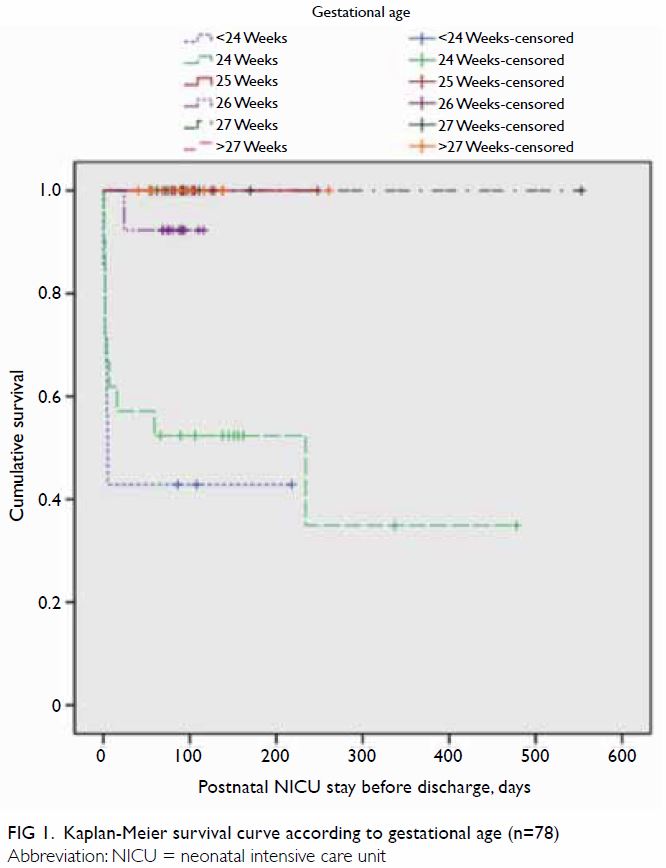

conotruncal CHDs (25 of 129; 19.4%) [P=0.04]. All seven patients with

22q11.2 deletion were found in the group of conotruncal CHDs and no

patients with 22q11.2 deletion were found in the group of non-conotruncal

CHDs (P<0.05). The details of these seven cases are shown in Table

4.

Table 2. Prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities in conotruncal, non-conotruncal, and all cardiac defects

Table 3. Additional copy number variations detected by array comparative genomic hybridisation apart from 22q11.2 deletion

Table 4. Copy number variations detected by array comparative genomic hybridisation, clinical features, and pregnancy outcomes for seven fetuses with 22q11.2 deletion

Among the whole cohort of 254 patients with

prenatal ultrasound diagnosis of CHDs, 101 (39.8%) patients had their

pregnancies terminated. There were 134 (52.8%) live births, nine (3.5%)

neonatal deaths, and four (1.6%) intrauterine deaths or miscarriages. Six

(2.4%) patients were lost for followup and could not be contacted for

their pregnancy outcomes.

Discussion

The data from this cohort demonstrated that 24.2%

of fetuses with CHDs detected by antenatal ultrasound were found to have

chromosomal abnormalities. The frequency of chromosomal abnormality in

fetuses with CHDs is much higher than the frequency of such abnormalities

in infants, because a large portion of these fetuses are terminated. A

2004 review found that up to 33% of fetal CHDs were associated with

chromosomal abnormalities1; this is

much higher than the prevalence in our cohort for two reasons. Firstly,

subtle defects such as right-sided aortic arch, persistent left superior

vena cava, and aberrant right subclavian artery were not included as CHDs

in the previous review. With advances in the ultrasonography resolution,

these subtle defects are detected with increasing frequency in recent

years. In the current cohort, up to 45 cases belong in this category, but

only four of them were found to have chromosomal abnormalities. Secondly,

most of our patients had combined biochemical screening or cell-free DNA

test in the first trimester for Down syndrome screening. If the screening

test was positive, an invasive test was performed and management offered

accordingly. Fetal CHDs may not be detectable at that early gestation, and

obstetricians may not have been focused on detecting cardiac abnormalities

at that time. Therefore, the true prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities

in CHDs in fetuses with common aneuploidies may be underestimated in our

cohort.

In the present study, non-conotruncal CHDs were

found to have a higher prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities than

conotruncal CHDs. Some types of CHDs, such as atrioventricular septal

defects and hypoplastic left heart syndrome, are associated with a higher

prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities than others, whereas some types of

CHDs, such as truncus arteriosus, are rarely associated with chromosomal

abnormalities. Invasive testing for karyotyping is generally recommended

for antenatally diagnosed CHDs, as the prevalence of chromosomal

abnormalities is up to 24.2%. Non-invasive prenatal testing may be

performed instead of karyotyping for some isolated cardiac abnormalities,

such as isolated small ventricular septal defects (VSDs), persistent left

superior vena cava, and aberrant right subclavian artery, when the purpose

is to exclude major aneuploidies such as trisomy 21.

The 22q11.2 deletion syndrome is also called

DiGeorge syndrome or velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Most patients with this

syndrome have a 1.5- to 3-Mb hemizygous deletion at chromosome 22q11.2

causing TBX1, CRKL, and MAPK1 gene

haploinsufficiency.18 This

syndrome is characterised by cardiac defects, cleft palate, thymic

hypoplasia, immune deficiency, hypocalcaemia, and learning difficulties.19 It has more than 180 associated

phenotypic features, with very variable genotype-phenotype correlations.

Congenital heart diseases remain one of the most important clinical

manifestations, and are present in 75% of patients with 22q11.2 deletion.19 The most common abnormalities

are conotruncal CHDs, among which tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) is the most

common.14 20 However, 22q11.2 deletion has also been reported in

patients with non-conotruncal CHDs such as isolated VSD.13 14 In a

cross-sectional survey of 392 patients with CHDs, the prevalence of

22q11.2 deletion was only 1.27%. Four out of the five confirmed patients

had conotruncal CHDs (interrupted aortic arch, truncus arteriosus, and

TOF); the other patient had non-conotruncal CHDs (VSD plus atrial septal

defect). Two patients had congenital extracardiac anomaly (one with arched

palate and micrognathia and one with hypertelorism).21 In a survey of 125 consecutive children in South

Africa with CHDs, the prevalence of 22q11.2 deletions was 4.8%. The

cardiac abnormalities in these confirmed patients included four with

conotruncal CHDs (tricuspid atresia with interrupted aortic arch,

tricuspid atresia with right-sided aortic arch, TOF, and VSD with

right-sided aortic arch), but also two isolated VSDs.22 The above two studies suggest that most patients with

22q11.2 deletions have conotruncal CHDs; although non-conotruncal CHDs are

possible, the prevalence is low.

The prevalence of 22q11.2 deletions in the Chinese

population has not been well documented. A study of 113 Chinese fetuses

with CHDs found that the frequency of 22q11.2 deletion was 5.3%.23 A recent study surveyed the prevalence of undiagnosed

22q11.2 deletions in 156 adult Hong Kong Chinese patients with conotruncal

CHDs by screening for 22q11.2 deletion syndrome using fluorescence

polymerase chain reaction and FISH. Eighteen (11.5%) patients were

diagnosed with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, translating into one previously

unrecognised diagnosis of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome in every 10 adults

with conotruncal CHDs. Extracardiac manifestations in these affected

individuals included velopharyngeal incompetence or cleft palate (44%),

hypocalcaemia (39%), neurodevelopmental anomalies (33%), thrombocytopenia

(28%), psychiatric disorders (17%), epilepsy (17%), and hearing loss

(17%). Those authors concluded that underdiagnosis in Chinese adults is

common and recognition of facial dysmorphic features can be affected by

age and ethnicity. Facial dysmorphic features may not be reliably

recognised in adult patients with CHDs in the clinical setting; therefore,

referral for genetic evaluation and molecular testing for 22q11.2 deletion

syndrome should be offered to patients with conotruncal CHDs.12

In contrast, in a small Chinese series, the

frequency of 22q11.2 deletion in three Chinese ethnic groups (Tai, Bai,

and Han people) with 19 sporadic CHDs was studied using genotype and

haplotype analysis with D22S420 in 11 consecutive polymorphic

microsatellite markers. Within this cohort, deletions at D22S944 were

found in two of four patients with TOF, one of five patients with VSD, and

one of five patients with patent ductus arteriosus. Those authors

concluded that sporadic 22q11.2 deletion could be detected in isolated

TOF, VSD, and patent ductus arteriosus in Chinese ethnic groups without

relevant family history of CHDs.13

The present study includes a larger sample size (207 fetuses) than the

previous two Chinese studies, but the detected prevalence of 22q11.2

deletion was only 3.4%. In addition, all seven fetuses with confirmed

22q11.2 deletion in the present study had conotruncal CHDs; none had

non-conotruncal CHDs or isolated VSD. The inclusion of patent ductus

arteriosus in the second study as CHDs is inconsistent with other studies.

Therefore those findings of 22q11.2 deletion associated with isolated CHDs

should be further evaluated in other populations.

The prevalence of 22q11.2 deletion in the present

study was 3.4% (7/207), which is comparable to that reported in the

literature. Because all patients had either 22q11FISH or aCGH testing, the

possibility of underdiagnosis was minimised. The cardiac abnormalities

identified in the confirmed cases were all conotruncal CHDs typical of

22q11.2 deletion syndrome. The deletions were not found in any cases with

non-conotruncal CHDs, suggesting that the occurrence of 22q11.2 deletion

in non-conotruncal CHDs in the local population is very low.

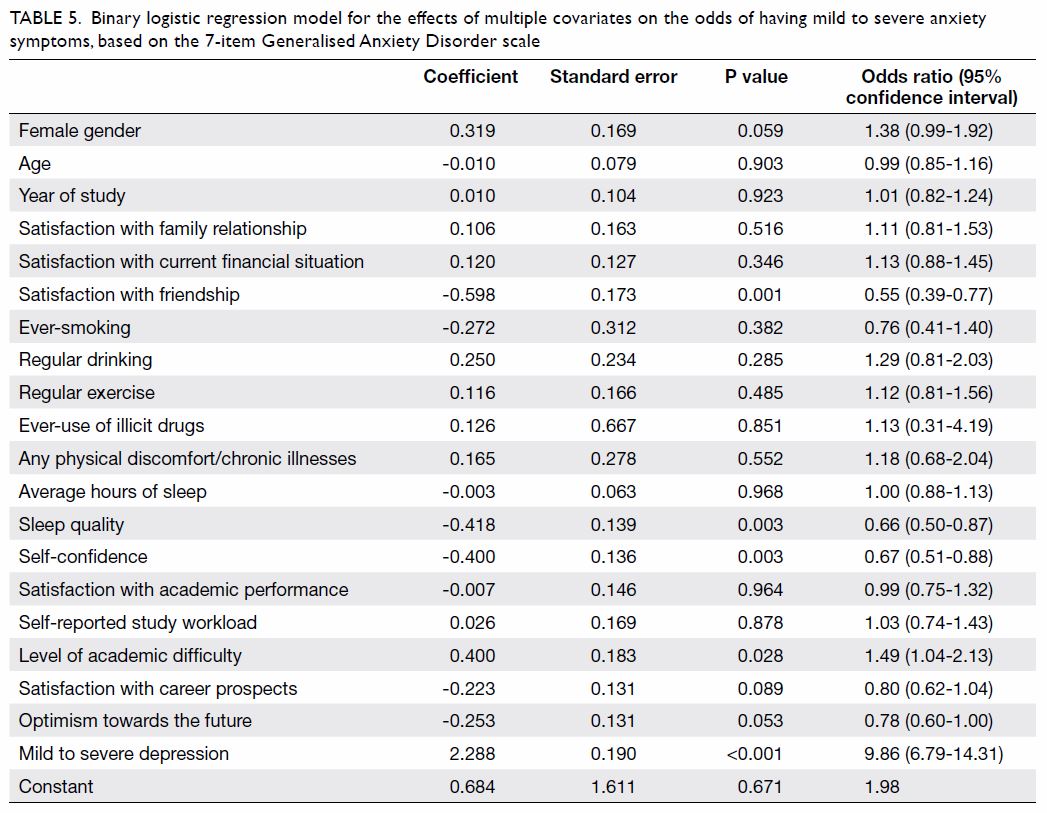

Array comparative genomic hybridisation is a

molecular cytogenetic technique to detect any CNVs within the genome. A

systematic review and meta-analysis on the use of aCGH on fetal CHDs that

included 1131 cases showed that the incremental yield of aCGH in detecting

CNVs after karyotyping and 22q11FISH analysis was 7%. An incremental yield

of 12% was found when 22q11.2 deletion cases were included.24 In the present study, aCGH detected four cases of

22q11.2 deletion and eight additional cases of CNVs. On the basis of the

deletion size in the four cases of 22q11.2 deletion, three should also be

detected by 22q11FISH; only the 61-kb deletion would not be detectable by

FISH. Therefore, if all patients in our cohort had karyotyping only

without 22q11FISH, aCGH would have an incremental yield of 6.0% (12/207).

If all our patients had karyotyping and 22q11FISH as first line, then aCGH

would have a further incremental yield of 4.3% (9/207). This incremental

rate for aCGH was lower than that reported previously.24 For patients in Hong Kong, aCGH is a self-financed

option. If fetal CHDs are detected antenatally, invasive testing with

karyotype and aCGH is offered to the patient on the basis of the potential

incremental yield of aCGH. In the present study, counselling for patients

whose fetus has Williams-Beuren syndrome or Phelan-McDermid syndrome would

be different from that for patients whose fetus has isolated cardiac

defects, as there would be other extracardiac manifestation such as mental

retardation. However, if patient declines self-paid aCGH, 22q11FISH should

be offered in addition to conventional karyotyping, because karyotyping

cannot readily detect 22q11.2 deletion.

Limitations

This study may have underestimated the prevalence

of chromosomal abnormalities, because 47 of our patients did not have

chromosomal analysis performed, 30 of whom were counselled as having minor

cardiac abnormalities or were normal variants (14 fetuses had isolated

small VSD, 10 had persistent left superior vena cava, four had right-sided

aortic arch, and two had aberrant right subclavian artery). However, none

of the babies were suspected or diagnosed to have chromosomal

abnormalities or DiGeorge syndrome after clinical assessment by

paediatrician after birth. Therefore, we assumed that there were no major

clinically significant chromosomal abnormalities in these babies.

Although the prevalence of 22q11.2 deletion is low,

testing for 22q11.2 deletion should be offered for fetuses with

conotruncal CHDs. Array comparative genomic hybridisation has an

additional incremental yield of around 5% on other microdeletions apart

from 22q11.2 deletion, and should be offered in addition to karyotyping

and 22q11FISH.

Author contributions

All authors had full access to the data,

contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and

take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Concept or design of the study: CW Kong, WWK To.

Acquisition of data: CW Kong, YKY Cheng.

Analysis or interpretation of data: CW Kong, YKY Cheng, WWK To, TY Leung.

Drafting of the manuscript: CW Kong.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: YKY Cheng, WWK To, TY Leung.

Acquisition of data: CW Kong, YKY Cheng.

Analysis or interpretation of data: CW Kong, YKY Cheng, WWK To, TY Leung.

Drafting of the manuscript: CW Kong.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: YKY Cheng, WWK To, TY Leung.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of

interest.

Declaration

The findings of this study were presented as poster

presentation in the 17th World Congress in Fetal Medicine, Athens, Greece,

24-28 June 2018.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for this study was granted by the

Kowloon Central/ Kowloon East Research Ethics Committee

(KC/KE-17-0183/ER-3) and the Joint CUHK-NTEC Clinical Research Ethics

Committee (NTEC-2017-0336). As this study was a retrospective review, the

need for individual patient consent was waived by the above two research

ethics committees.

References

1. Wimalasundera RC, Gardiner HM.

Congenital heart disease and aneuploidy. Prenat Diagn 2004;24:1116-22. Crossref

2. Hartman RJ, Rasmussen SA, Botto LD, et

al. The contribution of chromosomal abnormalities to congenital heart

defects: a population-based study. Pediatr Cardiol 2011;32:1147-57. Crossref

3. Ferencz C, Neill CA, Boughman JA, Rubin

JD, Brenner JI, Perry LW. Congenital cardiovascular malformations

associated with chromosome abnormalities: an epidemiologic study. J

Pediatr 1989;114:79-86. Crossref

4. Kidd SA, Lancaster PA, McCredie RM. The

incidence of congenital heart defects in the first year of life. J

Paediatr Child Health 1993;29:344-9. Crossref

5. Harris JA, Francannet C, Pradat P,

Robert E. The epidemiology of cardiovascular defects, part 2: a study

based on data from three large registries of congenital malformations.

Pediatr Cardiol 2003;24:222-35. Crossref

6. Schellberg R, Schwanitz G, Grävinghoff

L, et al. New trends in chromosomal investigation in children with

cardiovascular malformations. Cardiol Young 2004;14:622-9. Crossref

7. Reller MD, Strickland MJ,

Riehle-Colarusso T, Mahle WT, Correa A. Prevalence of congenital heart

defects in metropolitan Atlanta, 1998-2005. J Pediatr 2008;153:807-13. Crossref

8. Geng J, Picker J, Zheng Z, et al.

Chromosome microarray testing for patients with congenital heart defects

reveals novel disease causing loci and high diagnostic yield. BMC Genomics

2014;15:1127. Crossref

9. Zhu X, Li J, Ru T, et al. Identification

of copy number variations associated with congenital heart disease by

chromosomal microarray analysis and next-generation sequencing. Prenatal

Diagn 2016;36:321-7. Crossref

10. Zaidi S, Brueckner M. Genetics and

genomics of congenital heart disease. Circ Res 2017;120:923-40. Crossref

11. Rosa RF, Pilla CB, Pereira VL, et al.

22q11.2 Deletion syndrome in patients admitted to a cardiac pediatric

intensive care unit in Brazil. Am J Med Genet A 2008;146A:1655-61. Crossref

12. Liu AP, Chow PC, Lee PP, et al.

Under-recognition of 22q11.2 deletion in adult Chinese patients with

conotrunal anomalies: implications in transitional care. Eur J Med Genet

2014;57:306-11. Crossref

13. Jiang L, Duan C, Chen B, et al.

Association of 22q11 deletion with isolated congenital heart disease in

three Chinese ethnic groups. Int J Cardiol 2005;105:216-23. Crossref

14. Wozniak A, Wolnik-Brzozowska D,

Wisniewska M, et al. Frequency of 22q11.2 microdeletion in children with

congenital heart defects in western Poland. BMC Pediatr 2010;10:88. Crossref

15. Kan AS, Lau ET, Tang WF, et al.

Whole-genome array CGH evaluation for replacing prenatal karyotyping in

Hong Kong. PLoS One 2014;9:e87988. Crossref

16. Leung TY, Vogel I, Lau TK, et al.

Identification of submicroscopic chromosomal aberrations in fetuses with

increased nuchal translucency and apparently normal karyotype. Ultrasound

Obstet Gynecol 2011;38:314-9. Crossref

17. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock

SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening

the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement:

guidelines for reporting observational studies. Epidemiology

2007;18:800-4. Crossref

18. Koczkowska M, Wierzba J, Śmigiel R, et

al. Genomic findings in patients with clinical suspicion of 22q11.2

deletion syndrome. J Appl Genet 2017;58:93-8. Crossref

19. Digilio M, Marino B, Capolino R,

Dallapiccola B. Clinical manifestations of Deletion 22q11.2 syndrome

(DiGeorge/Velo-Cardio-Facial syndrome). Images Paediatr Cardiol

2005;7:23-34.

20. Lammer EJ, Chak JS, Iovannisci DM, et

al. Chromosomal abnormalities among children born with conotruncal cardiac

defects. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2009;85:30-5. Crossref

21. Huber J, Peres VC, de Castro AL, et

al. Molecular Screening for 22Q11.2 deletion syndrome in patients with

congenital heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol 2014;35:1356-62. Crossref

22. De Decker R, Bruwer Z, Hendricks L,

Schoeman M, Schutte G, Lawrenson J. Predicted v. real prevalence of the

22q11.2 deletion syndrome in children with congenital heart disease

presenting to Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital, South Africa: a

prospective study. S Afr Med J 2016;106(6 Suppl 1):S82-6. Crossref

23. Lv W, Wang S. Detection of chromosomal

abnormalities and the 22q11 microdeletion in fetuses with congenital heart

defects. Mol Med Rep 2014;10:2465-70.

24. Jansen FA, Blumenfeld YJ, Fisher A, et

al. Array comparative genomic hybridization and fetal congenital heart

defects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol

2015;45:27-35. Crossref