Hong

Kong Med J 2018 Aug;24(4):361–8 | Epub 30 Jul 2018

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj177081

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Delayed diagnosis of tuberculosis: risk factors and

effect on mortality among older adults in Hong Kong

Eric CC Leung, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)1;

CC Leung, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)1; KC Chang, MB, BS, FHKAM

(Medicine)1; CK Chan, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)1;

Thomas YW Mok, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)2; KS Chan, MB, BS,

FHKAM (Medicine)3; KS Lau, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)4;

CH Chau, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)5; Wilson KS Yee, MB, ChB,

FHKAM (Medicine)6; WS Law, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Medicine)1;

SN Lee, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Medicine)1; KF Au, MB, ChB, MRCP (UK)1;

LB Tai, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Medicine)1; WM Leung, MB, ChB, FHKAM

(Medicine)1

1 Tuberculosis and Chest Service, Centre

for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong Kong

2 Respiratory Medicine Department,

Kowloon Hospital, Homantin, Hong Kong

3 Pulmonary Service, Department of

Medicine, Haven of Hope Hospital, Tseung Kwan O, Hong Kong

4 Respiratory Medicine Department,

Ruttonjee Hospital, Wanchai, Hong Kong

5 Tuberculosis and Chest Unit, Grantham

Hospital, Wong Chuk Hang, Hong Kong

6 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics,

Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Eric CC Leung (eric_leung@dh.gov.hk)

Abstract

Objective: To assess the risk

factors and effects of delayed diagnosis on tuberculosis (TB) mortality

in Hong Kong.

Methods: All consecutive

patients with TB notified in 2010 were tracked through their clinical

records for treatment outcome until 2012. All TB cases notified or

confirmed after death were identified for a mortality survey on the

timing and causes of death.

Results: Of 5092 TB cases

notified, 1061 (20.9%) died within 2 years of notification; 211 (4.1%)

patients died before notification, 683 (13.4%) died within the first

year, and 167 (3.3%) died within the second year after notification.

Among the 211 cases with TB notified after death, only 30 were certified

to have died from TB. However, 52 (24.6%) died from unspecified

pneumonia/sepsis possibly related to pulmonary TB. If these cases are

counted, the total TB-related deaths increases from 191 to 243. In 82

(33.7%) of these, TB was notified after death. Over 60% of cases in

which TB was diagnosed after death involved patients aged ≥80 years and a

similar proportion had an advance care directive against resuscitation

or investigation. Independent factors for TB notified after death

included female sex, living in an old age home, drug abuse, malignancy

other than lung cancer, sputum TB smear negative, sputum TB culture

positive, and chest X-ray not done.

Conclusions: High mortality was

observed among patients with TB aged ≥80 years. Increased vigilance is

warranted to avoid delayed diagnosis and reduce the

transmission risk, especially among elderly patients with co-morbidities

living in old age homes.

New knowledge added by this study

- Mortality among elderly patients with tuberculosis (TB) in Hong Kong is high.

- There is a risk of institutional TB transmission because a substantial portion (42%) of these elderly people live in old age homes.

- Timely diagnosis and treatment of TB is necessary to avert adverse outcomes and prevent transmission.

- Increased vigilance and deployment of rapid diagnostic tools are necessary to facilitate early diagnosis of TB and to reduce the TB transmission risk, especially among elderly patients with co-morbidities living in old age homes.

Introduction

Over the past 30 years, the proportion of the Hong

Kong population aged ≥65 years doubled from 6.6% in 1981 to 13.3% in 2011.1 The proportion of those aged ≥65

years among patients with tuberculosis (TB) tripled from 13%2 to 39%3 in the

same period. Although the annual notification rate decreased from 149.1 to

65 per 100 000 population and the TB mortality rate decreased from 9.4 to

2.6 per 100 000 population from 1981 to 2011, the proportion of those aged

≥65 years increased from 53% to 82% among TB deaths.2 3 In older

adults, TB is associated with other co-morbidities, hospitalisation, and

delays in presentation and commencement of treatment.4 Missed opportunities for intervention might contribute

to the higher mortality rates in older adults, and might also increase the

risk of TB transmission. The present longitudinal study was conducted to

assess the effects of age on the mortality rates of patients with TB and

to elucidate the factors associated with missed TB diagnosis.

Methods

All consecutive cases of TB notified to the

Department of Health in 2010 were retrospectively collected from the

statutory TB notification registry. Hong Kong identity card numbers (or

passport numbers for non-residents) were retrieved from the notification

registry, together with date of notification, source of notification, and

demographic and clinical information. Further clinical information and

outcome data at 1 year after notification/initiation of treatment were

retrieved from the TB programme record forms.3

These forms are filed by the TB and Chest Service for patients managed

under its chest clinics and for patients managed by other health care

providers. Treatment outcome was classified according to the World Health

Organization (WHO) recommendations.5

Using the identity card number/passport number as the unique identifier,

the 2010 TB cohort data were cross-matched with the statutory death

registry from 1 January 2009 till 31 December 2012 for vital status, date

and cause(s) of death. All cases with a date of TB notification after the

date of death were recorded. A mortality survey was conducted on these

recorded cases by retrieving relevant clinical information from records in

public clinics and hospitals.

The demographics, co-morbidities, treatment

outcomes, and mortality pattern of the cohort were analysed. Published

data on patients of all ages with TB6

and on elderly patients with TB7

notified in 1996 were used for comparison. A date of TB notification after

the date of death was considered as a surrogate marker of delayed

diagnosis. Categorical variables were analysed by Pearson χ2

test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate; continuous variables were

analysed by Mann-Whitney U test. Binary regression modelling was

used to calculate the adjusted odds ratios (aORs) for risk factors for

delayed diagnosis of TB after death using a backward conditional approach,

with probability to remove being 0.10 and to retain being 0.05. A

two-tailed P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical

analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows, version 16.0 (SPSS Inc,

Chicago [IL], US).

Results

After exclusion of 336 cases subsequently

denotified because of alternative diagnoses, a total of 5092 patients with

TB were included in the 2010 TB cohort, at a notification rate of 72.5/100

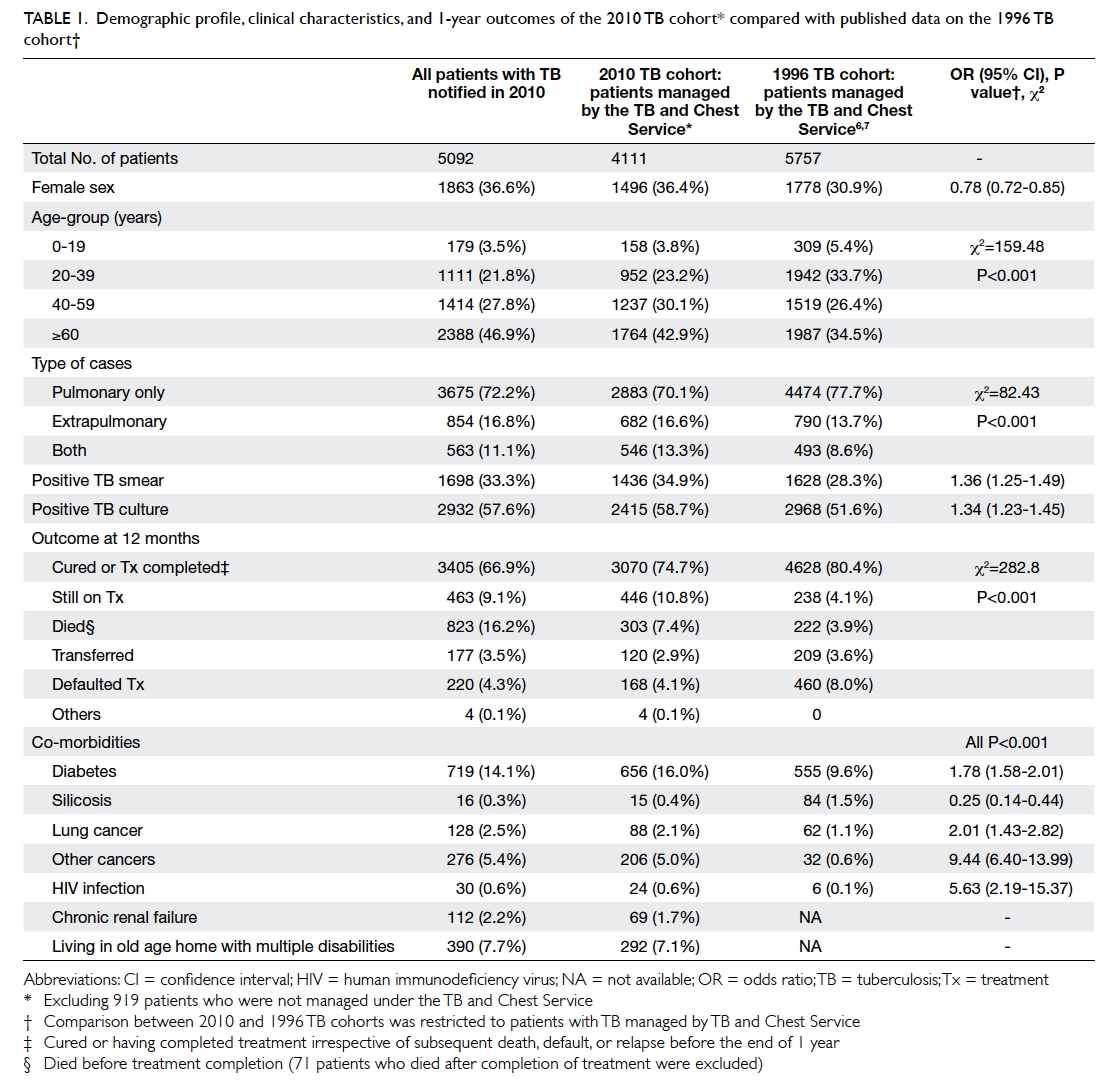

000 person-years. Table 1 summarises their demographic data, clinical

characteristics, and 1-year outcomes. Comparison with published data on

the 1996 TB cohort6 7 was restricted to patients managed under the TB and

Chest Service, for which the proportion of patients with TB aged ≥60 years

increased from 34.5% in 1996 to 42.9% in 2010. There were more

co-morbidities such as diabetes mellitus (16.0% vs 9.6%), lung cancer

(2.1% vs 1.1%), and other cancers (5.0% vs 0.6%) in the 2010 TB cohort

than in the 1996 TB cohort (χ2 test, P<0.001). In 2010, the

proportion of patients who died before completion of TB treatment was

smaller for those managed under the TB and Chest Service (7.4%) than for

the overall cohort (16.2%). However, the proportion of patients managed

under the TB and Chest Service who died before completion of TB treatment

nearly doubled between 1996 (3.9%) and 2010 (7.4%).

Table 1. Demographic profile, clinical characteristics, and 1-year outcomes of the 2010 TB cohort compared with published data on the 1996 TB cohort

Among 5092 TB notifications, 1061 (20.9%) deaths

occurred within 2 years of notification. Of the 1061 deaths, 211 (4.1%)

occurred before the TB notification (ie, TB was notified after death;

median delay in notification [interval between death and TB notification]

45 days, interquartile range 30-65 days). Of the deaths after

notification, 683 (13.4%) died in the first year and 167 (3.3%) died in

the second year. The reported causes of death were related to TB in only

191 (18.0%) of all deaths; 30 (14.2%) before TB notification, 158 (23.1%)

in the first year, and three (1.8%) in the second year after notification.

Among the 211 deaths before TB notification, only

30 (14.2%) had TB as the main cause of death. There were 54 cases of

‘pneumonia unspecified’ and three cases of ‘sepsis unspecified’ reported

as main cause of death. Of these cases, only five with potential causative

organisms, such as Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, or Escherichia coli,

were identified. However, in the sputum that had been collected before

death in these patients, Mycobacterium tuberculosis was

subsequently isolated after prolonged culture, indicating that TB was the

likely main cause of death in the remaining 52 deaths initially reported

as ‘sepsis or pneumonia unspecified’. Including these revised results

increases the 2010 TB-related mortality from 191 to 243, ie, an increase

of 27% from the officially reported mortality figures of 2.6 to 3.4 per

100 000 person-years.8 The

corresponding proportion of TB-related mortality increases to 38.8%

(82/211) in cases with TB notified after death compared with 23.3%

(158/683) who died in the first year after notification and 1.7% (3/167)

who died in the second year. Therefore, a substantial proportion (15.5%)

of TB-related deaths could potentially have been prevented by early

diagnosis and treatment.

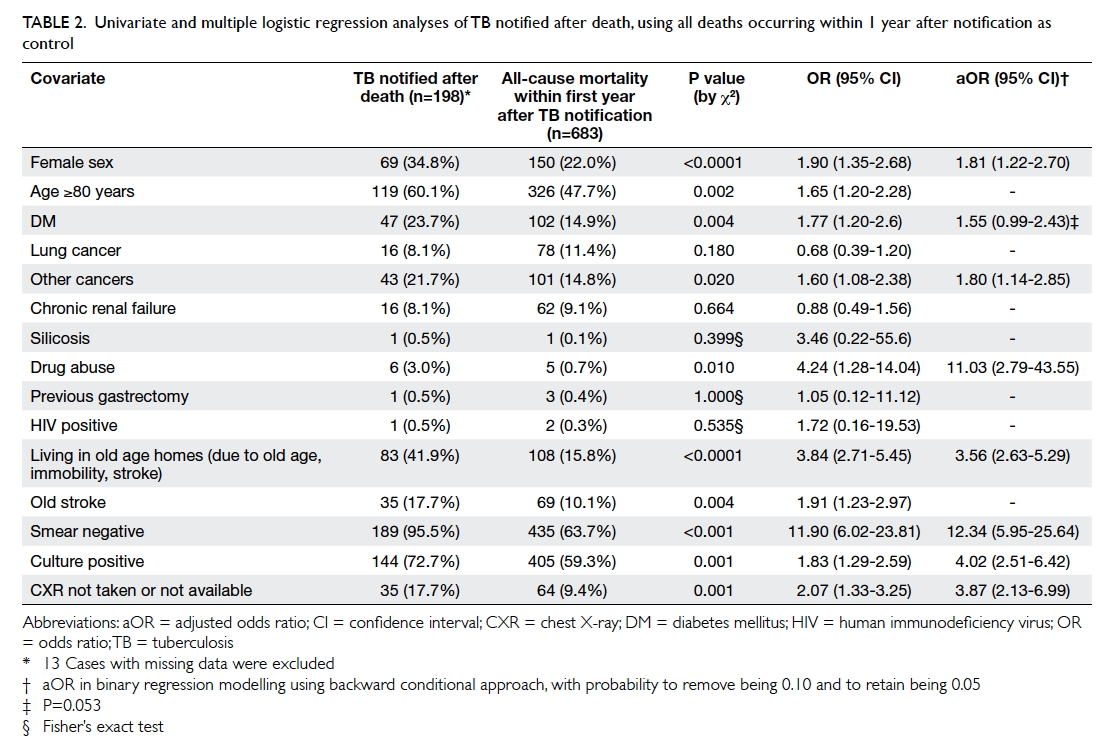

For the 211 deaths before TB notification, 25 cases

of TB were notified from the public mortuary. Of the remaining 186 cases

of TB that were notified from hospital, 173 hospital records were

collected; 13 cases had missing data. None of the 198 patients with

retrievable records were started on treatment. Of these 198 patients, 119

(60.1%) were aged ≥80 years at the time of death, and 93 (47%) had more

than one admission to hospital before death. Prior to death, of these 198

patients, 83 (41.9%) were living in an old age home (OAH), 78 (39.4%) were

bed-ridden, and 121 (61.1%) had an advance care directive such as ‘do not

resuscitate’ or ‘do not investigate’ stated in the case notes. Table

2 summarises the univariate and multiple logistic regression

analyses of these 198 early deaths, using deaths occurring within 1 year

after notification as controls. Female sex, having a malignancy other than

lung cancer, living in an OAH, drug abuser, sputum TB smear negative,

sputum TB culture positive, and chest X-ray (CXR) not done or not

available were independent risk factors for death before TB diagnosis.

Table 2. Univariate and multiple logistic regression analyses of TB notified after death, using all deaths occurring within 1 year after notification as control

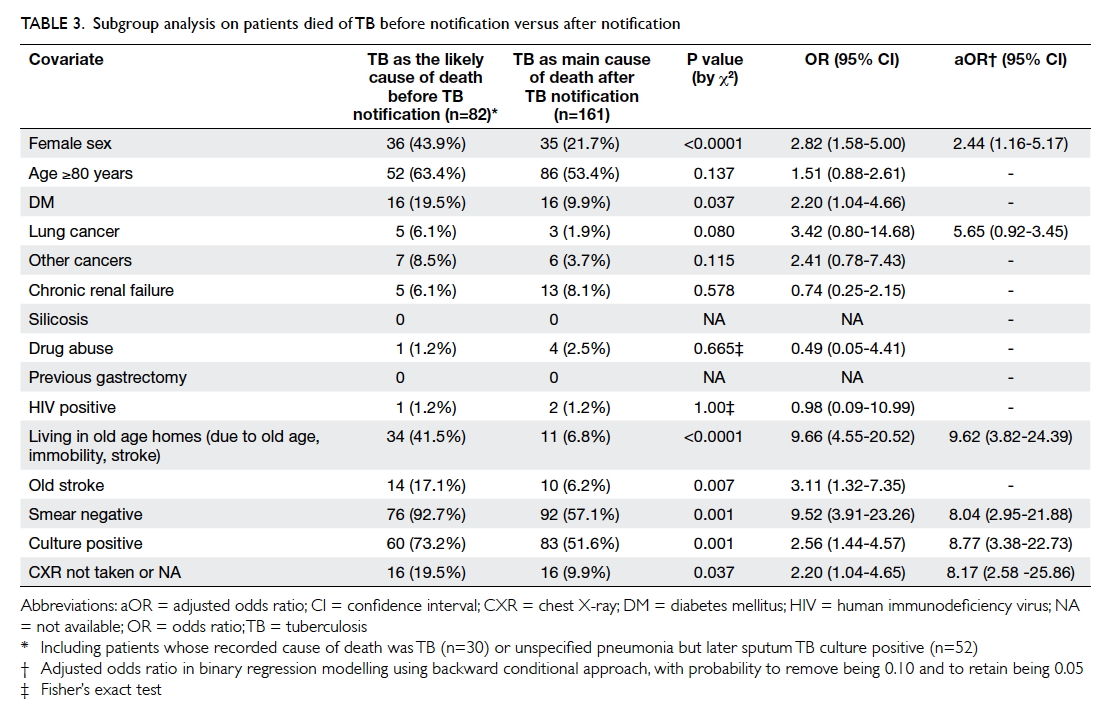

Subgroup analysis was carried out for patients that

most likely died of TB. The study group included the 30 patients who died

of TB before diagnosis and the 52 patients whose deaths were initially

reported as ‘sepsis or pneumonia unspecified’ but later sputum TB culture

was positive. The control group was all patients who died of TB after

notification (Table 3). Female sex, living in an OAH, sputum TB

smear negative, sputum TB culture positive, and CXR not done or not

available were independent risk factors for this group.

Discussion

In the present study, the proportion of patients

with TB aged ≥60 years increased by 25% from 1996 to 2010. However, over

the same interval, the proportion of patients who had died before

completion of treatment nearly doubled (Table 1). A substantial proportion (211 of 1061;

19.9%) of the TB-related deaths were notified after death. Over 60% of

these cases were aged ≥80 years and none were started on treatment,

suggesting a failure to detect TB rather than just a delay in

notification. Over 60% of them had an advance care directive against

resuscitation or investigation, likely indicating a concurrent terminal

illness. Independent factors associated with TB notified after death were

female sex, malignancies other than lung cancer, living in an OAH, drug

abuse, sputum TB smear negative, sputum TB culture positive, and CXR not

done. Although the recorded cause of death was TB in only 30 (14%) cases,

in 52 (25%) cases the recorded cause of death was respiratory disease

(predominantly pneumonia unspecified), particularly among those aged ≥80

years (19% vs 39%; P<0.005). In these cases, pulmonary TB is likely to

have been the main or precipitating cause.

In the present study, the fatality rate in the

first year of TB notification was 17.5% (4.1% died before TB notification

and 13.4% died within 1 year after TB notification). This is much higher

than rates reported earlier in Europe (7.8%9)

and England and Wales (8.4%10),

but similar to rates reported more recently in Taiwan (16.5%11). This is probably a reflection of differences among

patient profiles in these regions, especially age and the associated

co-morbidities. In the present study, 47% of patients with TB were aged

≥60 years (Table 1), whereas in the studies in Europe and the

United Kingdom only 24.3%9 and 17.9%10 of the patients with TB were cohort

aged ≥60 years.

Our finding that 4.1% of TB cases were notified

after death is similar to rates reported in Taiwan in 2006 (4.0%12) and in the US in the 1980s (5.1%13 and 3.9%14).

In all of these reports, advanced age was a consistent observation for

this extreme form of delayed diagnosis. As expected from the relatively

short turnover time for sputum TB smear tests and CXRs, sputum TB smear

negative, and CXR unknown or not done were important risk factors for TB

notified after death. The strong association between these cases and

positive sputum TB culture might be explained by the fact that the sputum

TB culture was the primary method of TB diagnosis, unless a diagnosis had

already been made during autopsy.

Our findings that drug abusers have a higher chance

of TB notification after death is in line with an earlier study that

suggested such patients have difficulty completing medical evaluations.15 Drug abusers might be less aware

of their TB symptoms because of the effects of the drugs taken, such as

opiate suppression of the cough reflex.

Female sex was also an independent factor in the

current study, similar to a previous study in Taiwan.11 This is expected, because there is a higher

proportion of women among the geriatric population16 and among residents of OAH17

owing to their longer life expectancy and because conservative treatment

is more frequently selected by these elderly female patients or their

guardians. Patients with terminal conditions might have an advance care

directive against resuscitation or investigation. An incorrect provisional

diagnosis might also result from the readiness to accept a diagnosis of

advanced disseminated malignancy in a patient with such an advance care

directive. As lung cancer patients usually had CXR and sputum samples

taken in their initial diagnostic investigation, coexisting TB could be

discovered early. In addition, most lung cancer patients were diagnosed at

an advanced stage and usually died within the first year after

presentation.18

In our study, TB-related death occurred shortly

before or after TB treatment was started, in line with findings from

studies in Taiwan,19 the US,20 and Russia21

reporting a median time of 3 to 7 weeks from diagnosis or notification of

TB to death. A study in Canada showed that a delay in TB treatment

increased risk of death (aOR=3.3; 95% confidence interval=1.7-6.2) and

intensive care unit admission (aOR=16.8; 95% confidence interval=2-144).22 Another study of hospitalised

patients with TB also showed that late TB treatment guided by conventional

TB culture was associated with a higher mortality than for treatment

guided by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), liquid culture, positive

histological findings or typical clinico-radiological manifestation.23 In settings with a high human immunodeficiency virus

prevalence, the WHO advocates early empirical TB treatment based on

clinical and radiological criteria in patients strongly suspected as

having TB but with sputum TB smear negative, because this can improve

survival.24 25

Although a timely diagnosis might not avert most

non–TB-related deaths, early treatment could reduce the institutional

transmission risk, because 42% of patients with TB were living in OAHs in

the current study. The prevalence of active TB in OAHs has been estimated

to be as high as 669 per 100 000 person-years in Hong Kong.26 The majority of patients in the present study did not

have a positive sputum TB smear; however, a representative sputum sample

might have been difficult to obtain from patients living in OAHs. That 73%

of these patients had a positive sputum TB culture suggests that there was

a sufficient degree of suspicion, either clinical or radiological, for

initiation of bacteriological sampling. In total, 54 out of 211 patients

who died before TB notification were recorded to have ‘pneumonia

unspecified’ or ‘respiratory disease’ as the main cause of death. Past

studies have shown that negative TB smear contributed to around 17% of TB

transmission in San Francisco27

and Vancouver28 and even 30% in

China.29 Thus, rapid diagnosis

with effective isolation and early treatment can reduce transmission and

even mortality. Sputum induction30

or gastric aspiration31 would

improve specimen collection. However, in view of the infection risk, these

bio-aerosol generating procedures would preferentially be performed in a

negative pressure room with effective personal protective equipment as

stipulated by the Institutional Infection Control Guidelines. Real-time

PCR diagnostic tests such as Xpert® MTB/RIF assay32

may also be valuable, either as a primary diagnostic test or as an add-on

test in patients previously found to be TB smear negative, to avoid the

long turnover time for bacteriological cultures. In a study in Hong Kong,33 Xpert® MTB/ RIF assay was found

to be a highly cost-effective strategy for TB diagnosis in terms of

quality-adjusted life-years gained and lower first year mortality rate.

Higher mortality among patients with TB aged ≥80

years is a consistent finding among different TB programmes.34 The present study also found frequently missed

diagnosis of TB and excessive mortality among patients aged ≥80 years who

were frequently institutionalised and had multiple co-morbidities. A high

index of suspicion and rapid diagnostic tools are necessary to reduce both

mortality and transmission risk in a rapidly ageing population, in order

to meet the WHO End TB 2035 target of a 95% reduction in TB mortality rate

compared with the 2015 rate.35

This study shares an important limitation with

other retrospective studies. The clinical data in this cohort were

constructed from a database of the pre-assembled ‘TB programme record

form’ which was not specifically designed for this study. Therefore, not

all pertinent risk factors were identified and recorded. As this is a

population-wide database, many health care professionals were involved and

the measurement of risk factors and outcomes is less accurate and less

consistent than a prospective study. Nonetheless, data from the TB

programme record form have been used in previous studies on patients with

TB6 and elderly patients with TB7 and were included for comparison in this

study.

Conclusions

This study was a collaborative effort between the

Hospital Authority and the Department of Health, and a database was

compiled for all patients with TB treated in the public or the private

sector. This study provides insight into the mortality of patients with TB

and the risk factors associated with a delay in TB diagnosis. These

factors include novel patient factors such as female sex, living in OAHs,

advance care directives refusing further investigation or resuscitation,

and drug abuse. Additional factors include lack of a representative sputum

sample. which could be mitigated by sputum induction or gastric

aspiration, and the relative insensitivity of sputum TB smear and long

turnover time for conventional TB culture, which could be mitigated by

using of real-time PCR tests. Information generated by this study will

help frontline clinicians to be better aware of this important infectious

disease among elderly people. Hopefully, more resources will be allocated

to promote rapid diagnosis of TB for patients in high-risk scenarios in

Hong Kong.

Acknowledgement

The authors would likely to thank the Nursing and

General Grade staff in Department of Health and Hospital Authority for

their assistance in collection and compilation of the demographical,

clinical and laboratory data for this study.

Author contributions

Concept or design: ECC Leung, CC Leung, CK Chan, KC

Chang.

Acquisition of data: TYW Mok, KS Chan, KS Lau, CH Chau, WKS Yee, WM Leung, KF Au.

Analysis or interpretation of data: WS Law, SN Lee, LB Tai.

Drafting of the article: ECC Leung, CC Leung, WM Leung, WS Law.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: TYW Mok, KS Chan, KS Lau, CH Chau, WKS Yee, WM Leung, KF Au.

Analysis or interpretation of data: WS Law, SN Lee, LB Tai.

Drafting of the article: ECC Leung, CC Leung, WM Leung, WS Law.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: All authors.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration

The authors have no conflicts of interest to

disclose.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

the Department of Health and Ethics Committees of all hospital clusters

from the Hospital Authority.

References

1. Demographic Statistics Section, Census

and Statistics Department, Hong Kong SAR Government. Demographic Trends in

Hong Kong 1981-2011. Available from:

https://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B1120017032012XXXXB0100.pdf Accessed 13

Jul 2018. Crossref

2. Tuberculosis and Chest Service,

Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Annual Report 1981. Hong

Kong: Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government; 1981. Crossref

3. Tuberculosis and Chest Service,

Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Annual Report 2011.

Available from: http://www.info.gov.hk/tb_chest/doc/AnnualReport2011.pdf.

Accessed 14 Jul 2018. Crossref

4. Leung CC, Yew WW, Chan CK, et al.

Tuberculosis in older people: a retrospective and comparative study from

Hong Kong. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:1219-26. Crossref

5. World Health Organization. Definitions

and reporting framework for tuberculosis—2013 revision. Geneva,

Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2013. Crossref

6. Tam CM, Leung CC, Noertjojo K, Chan SL,

Chan-Yeung M. Tuberculosis in Hong Kong-patient characteristics and

treatment outcome. Hong Kong Med J 2003;9:83-90.

7. Chan-Yeung M, Noertjojo K, Tan J, Chan

SL, Tam CM. Tuberculosis in the elderly in Hong Kong. Int J Tuberc Lung

Dis 2002;6:771-9.

8. Centre for Health Protection, Department

of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Notification & death rate of

tuberculosis (all forms), 1947-2017. Available from:

https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/statistics/data/10/26/43/88.html. Accessed 20

Jul 2018. Crossref

9. Lefebvre N, Falzon D. Risk factors for

death among tuberculosis cases: analysis of European surveillance data.

Eur Respir J 2008;31:1256-60. Crossref

10. Crofts JP, Pebody R, Grant A, Watson

JM, Abubakar I. Estimating tuberculosis case mortality in England and

Wales, 2001-2002. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2008;12:308-13.

11. Wu YC, Lo HY, Yang SL, Chu DC, Chou P.

Comparing the factors correlated with tuberculosis-specific and

non-tuberculosis-specific deaths in different age groups among

tuberculosis-related deaths in Taiwan. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0118929. Crossref

12. Wu YC, Lo HY, Yang SL, Chou P. Factors

correlated with tuberculosis reported after death. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis

2014;18:1485-90. Crossref

13. Rieder HL, Kelly GD, Bloch AB, Cauthen

GM, Snider DE Jr. Tuberculosis diagnosed at death in the United States.

Chest 1991;100:678-81. Crossref

14. DeRiemer K, Rudoy I, Schecter GF,

Hopewell PC, Daley CL. The epidemiology of tuberculosis diagnosed after

death in San Francisco, 1986-1995. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 1999;3:488-93.

15. Deiss RG, Rodwell TC, Garfein RS.

Tuberculosis and illicit drug use: review and update. Clin Infect Dis

2009;48:72-82. Crossref

16. Census and Statistics Department, Hong

Kong SAR Government. Population by Age Group and Sex. Hong Kong Population

By-Census Main Report. 2015. Available from:

http://www.censtatd.gov.hk/hong_kong_statistics/statistical_tables/index.jsp?charsetID=1<tableID=002.

Accessed 16 Mar 2016.

17. Luk JK, Chan FH, Pau MM, Yu C.

Outreach geriatric service to private old age homes in Hong Kong West

Clusters. J HK Geriatr Soc 2002;11:5-11.

18. Cancer Research UK. Lung cancer

survival statistics. Available from:

http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/healthprofessional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/lung-cancer/survival.

Accessed 15 Mar 2016. Crossref

19. Lin CH, Lin CJ, Kuo YW, et al.

Tuberculosis mortality: patient characteristics and causes. BMC Infect Dis

2014;14:5. Crossref

20. Oursler KK, Moore RD, Bishai WR,

Harrington SM, Pope DS, Chaisson RE. Survival of patients with pulmonary

tuberculosis: clinical and molecular epidemiologic factors. Clin Infect

Dis 2002;34:752-9. Crossref

21. Mathew TA, Ovsyanikova TN, Shin SS, et

al. Causes of death during tuberculosis treatment in Tomsk Oblast Russia.

Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2006;10:857-63.

22. Greenaway C, Menzies D, Fanning A, et

al. Delay in diagnosis among hospitalized patients with active

tuberculosis—predictors and outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med

2002;165:927-33. Crossref

23. Lui G, Wong RY, Li F, et al. High

mortality in adults hospitalized for active tuberculosis in a low HIV

prevalence setting. PLoS One 2014;9:e92077. Crossref

24. Holtz TH, Kabera G, Mthiyane T, et al.

Use of a WHO-recommended algorithm to reduce mortality in seriously ill

patients with HIV infection and smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis in

South Africa: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis

2011;11:533-40. Crossref

25. Katagira W, Walter ND, Den Boon S, et

al. Empiric TB treatment of severely ill patients with HIV and presumed

pulmonary TB improves survival. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr

2016;72:297-303. Crossref

26. Chan-Yeung M, Chan FH, Cheung AH, et

al. Prevalence of tuberculous infection and active tuberculosis in old age

homes in Hong Kong. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:1334-40. Crossref

27. Behr MA, Warren SA, Salamon H, et al.

Transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from patients

smear-negative for acid-fast bacilli. Lancet 1999;353:444-9. Crossref

28. Hernández-Garduño E, Cook V, Kunimoto

D, Elwood RK, Black WA, FitzGerald JM. Transmission of tuberculosis from

smear negative patients: a molecular epidemiology study. Thorax

2004;59:286-90. Crossref

29. Yang C, Shen X, Peng Y, et al.

Transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in China; a

population-based molecular epidemiologic study. Clin Infect Dis

2015;61:219-27. Crossref

30. Chang KC, Leung CC, Yew WW, Tam CM.

Supervised and induced sputum among patients with smear-negative pulmonary

tuberculosis. Eur Respir J 2008;31:1085-90. Crossref

31. Brown M, Varia H, Bassett P, Davidson

RN, Wall R, Pasvol G. Prospective study of sputum induction, gastric

washing, and bronchoalveolar lavage for the diagnosis of pulmonary

tuberculosis in patients who are unable to expectorate. Clin Infect Dis

2007;44:1415-20. Crossref

32. Steingart KR, Schiller I, Horne DJ,

Pai M, Boehme CC, Dendukuri N. Xpert® MTB/RIF assay for pulmonary

tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance in adults. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev 2014;(1):CD009593. Crossref

33. You JH, Lui G, Kam KM, Lee NL.

Cost-effectiveness analysis of the Xpert MTB/RIF assay for rapid diagnosis

of suspected tuberculosis in an intermediate burden area. J Infect

2015;70:409-14. Crossref

34. Waitt CJ, Squire SB. A systematic

review of risk factors for death in adults during and after tuberculosis

treatment. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011;15:871-85. Crossref

35. World Health Organization.

Implementing the end TB strategy: the essentials. Available from:

http://www.who.int/tb/publications/2015/The_Essentials_to_End_TB/en/.Accessed

3 May 2017. Crossref