Substance abuse effects on urinary tract: methamphetamine and ketamine

Hong Kong Med J 2019 Dec;25(6):438–43 | Epub 4 Dec 2019

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Substance abuse effects on urinary tract:

methamphetamine and ketamine

CH Yee, MB, BS, FRCS (Edin)1; CF Ng,

MB, ChB, FRCS (Edin)1; YL Hong, MSc2; PT Lai, BN1;

YH Tam, MB, ChB, FRCS (Edin)2

1 Department of Surgery, SH Ho Urology

Centre, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

2 Department of Surgery, The Chinese

University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr CH Yee (yeechihang@surgery.cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Ketamine is known

to cause urinary tract dysfunction. Recently, methamphetamine (MA) abuse

has become a growing problem in Asia. We investigated the symptomatology

and voiding function in patients who abused MA and ketamine and compared

their urinary tract toxicity profiles.

Methods: In the period of 23

months from 1 October 2016, all consecutive new cases of patients

presenting with MA- or ketamine-related urological disorder were

recruited into a prospective cohort. Polysubstance abuse patients were

excluded. Data were analysed by comparison between patients with

ketamine abuse and MA abuse. Basic demographic data and initial

symptomatology were recorded, and questionnaires on urinary symptoms and

the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) were used as assessment tools.

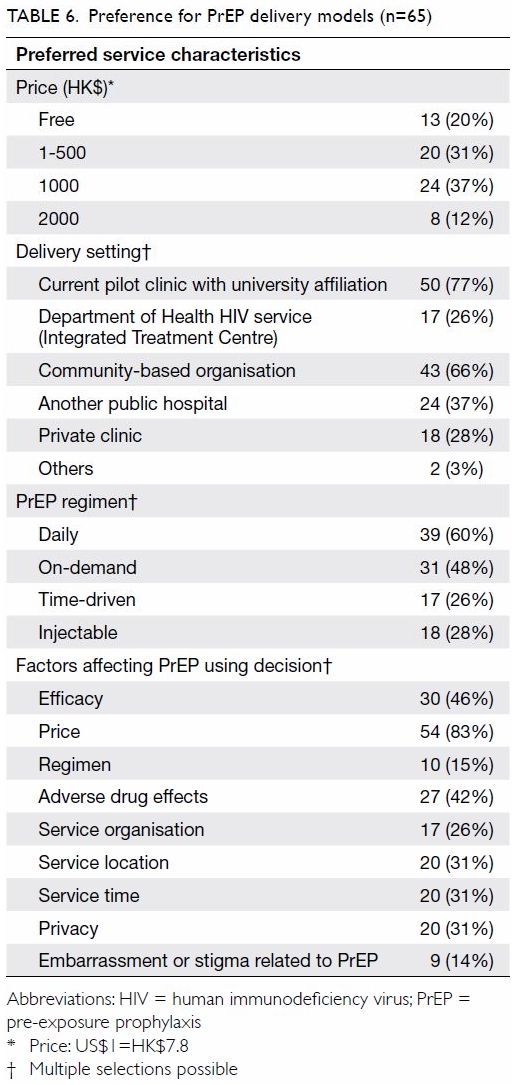

Results: Thirty-eight patients

were included for analysis. There was a statistically significant

difference in mean age between patients with MA and ketamine abuse (27.2

± 7.2 years and 31.6 ± 4.8 years, respectively, P=0.011). Urinary

frequency was the most common urological symptom in our cohort of

patients. There was a significant difference in the

prevalence of dysuria (ketamine 43.5%, MA 6.7%, P=0.026) and a

significant trend in the difference in hesitancy (ketamine 4.3%, MA

26.7%, P=0.069). Overall, questionnaires assessing urinary storage

symptoms and voiding symptoms did not find a statistically significant

difference between the two groups. The MoCA revealed that both groups

had cognitive impairment (ketamine 24.8 ± 2.5, MA 23.6 ± 2.9, P=0.298).

Conclusions: Abuse of MA caused

urinary tract dysfunction, predominantly storage symptoms. Compared with

ketamine abuse, MA abuse was not commonly associated with dysuria or pelvic

pain.

New knowledge added by this study

- Conventionally, methamphetamine has mainly been implicated for its neurological impact. Our study illustrated the impact of methamphetamine on the urinary tract, ie, an increase in storage symptoms.

- Cognitive impairment from ketamine abuse was also documented in our study with a valid assessment.

- Management of methamphetamine and ketamine abuse should involve multiple disciplines to improve the comprehensiveness of assessment and treatment.

Introduction

Both the range of available drugs and the scope of

drug markets are expanding and diversifying. Abuse of substances such as

amphetamine-type stimulants, cannabis, and cocaine are major global health

concerns. According to World Health Organization statistics, the number of

cannabis users increased from 183 million in 2015 to 192 million in 2016

worldwide, whereas 34 million people abuse amphetamines and prescription

stimulants.1

While the spectrum of substance abuse can be wide,

many forms of illicit drug use inevitably induce toxicity and detrimental

effects on the urinary tract. Smoking cannabis was found to have a

significant association with bladder cancer in a hospital-based

case-control study,2 attributed to

the common carcinogens present in cannabis and tobacco smoke.3 Acute renal infarction has been observed in patients

who used cocaine.4 Ketamine has

received particular attention in the past few years for its impacts on

both the upper and lower urinary tract.5

It has been one of the most commonly abused substances by teenagers since

2005 in Asian cities such as Hong Kong.6

In recent years, methamphetamine (MA) abuse has

also become a serious and growing problem in Asia.7 The proportion of people abusing MA increased from

28.8% to 75.1% over a span of 5 years in China.8

Japan has seen its third epidemic of MA abuse since 1995.9 South Korea has also had an increase in psychotropic

drug abuse, predominantly MA, from 7919 people in 2014 to 11 396 in 2016.10 In Hong Kong, 25.9% of people

who abused drugs had exposure to amphetamine-type psychotropic substances

in 2017.11 While the psychological

and neurological effects of MA have been widely discussed, the urological

aspects of the drug’s side-effects have not yet been well documented in

the literature. We investigated the symptomatology and voiding function in

a cohort of patients who abused the two most common psychotropic

substances in our locality, namely MA and ketamine, and compared their

urinary tract toxicity profiles.

Methods

In the period of 23 months from 1 October 2016, all

consecutive new cases of patients who attended our centre for MA- or

ketamine-related urological disorders were seen in a dedicated clinic and

were recruited into a prospective cohort. Ethics committee approval was

granted for the study (CREC Ref CRE-2011.454). Written informed consent

was given by all participants before entering the study.

Basic demographic data were recorded before clinic

attendance, including age, sex, employment status, drinking habits, and

smoking history. Habits of substance abuse were characterised. Serum

creatinine levels, urine microscopy and culture, and uroflowmetry were

measured. Initial symptomatology enquiry included the presence and

characteristics of frequency, urgency, suprapubic pain, haematuria,

hesitancy, intermittency, and incomplete emptying. Functional bladder

capacity was calculated by adding the voided volume to post-void urine

residuals during the uroflowmetry assessment. Urological symptoms were

assessed with the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) or the

Overactive Bladder Symptom Score (OABSS).12

The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) was used to assess

sexual function in male respondents who were sexually active in the

preceding 4 weeks. Another component of symptom assessment was the Pelvic

Pain and Urgency/Frequency (PUF) patient symptom scale. The Chinese

version of the PUF symptom scale is a validated assessment tool for

cystitis.13 For cognitive

dysfunction, we employed the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) as an

assessment tool. Chu et al14

proved the validity and reliability of the Cantonese Chinese MoCA as a

brief screening tool for cognitive impairment.

Polysubstance abuse patients were excluded. Data

were analysed by comparison between two groups of patients, namely those

with ketamine abuse only and those with MA abuse only. Descriptive

statistics were used to characterise the clinical characteristics of the

study cohort. Chi squared tests were used for categorical data, and

Mann-Whitney U tests were used for continuous data. A P value of

<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. The SPSS

(Windows version 24.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States) was used for

all calculations.

Results

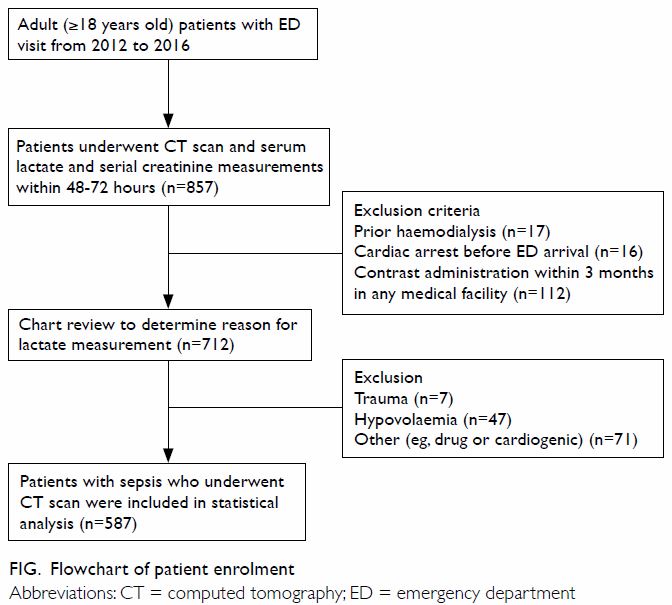

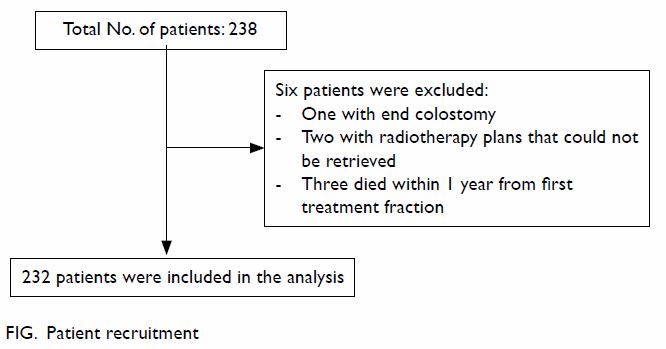

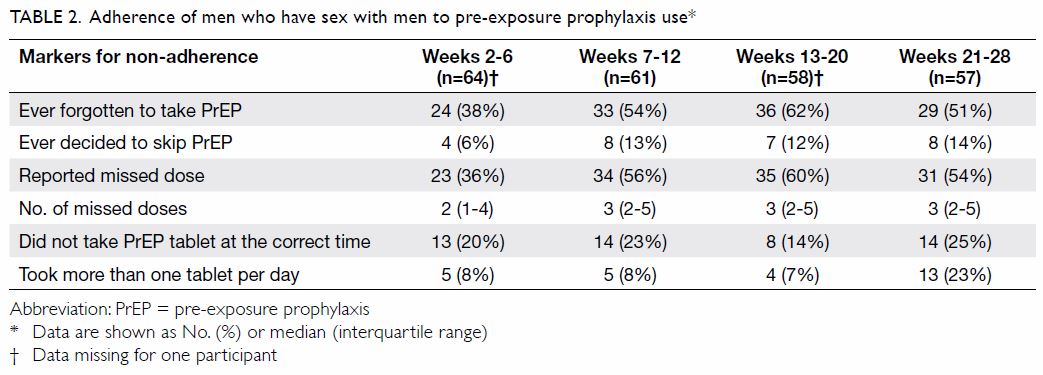

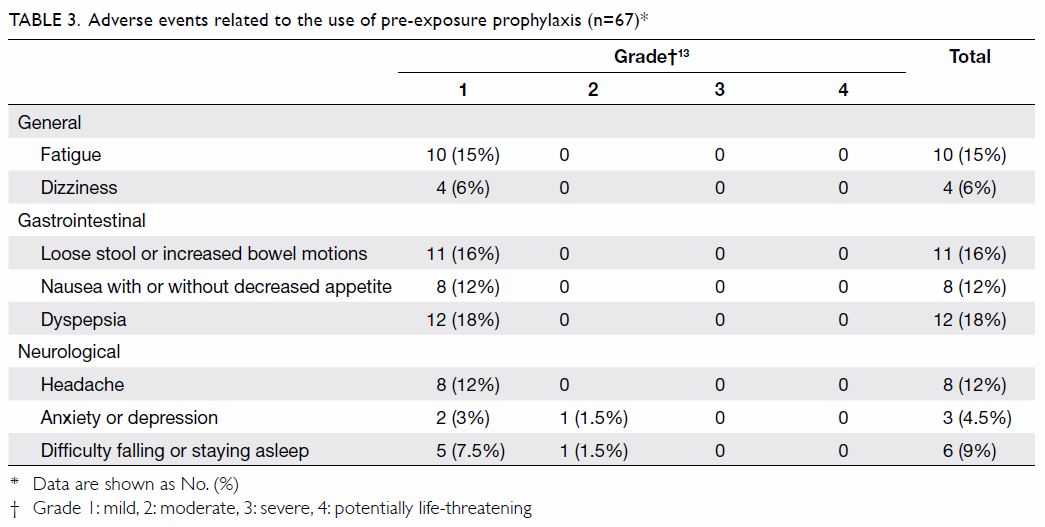

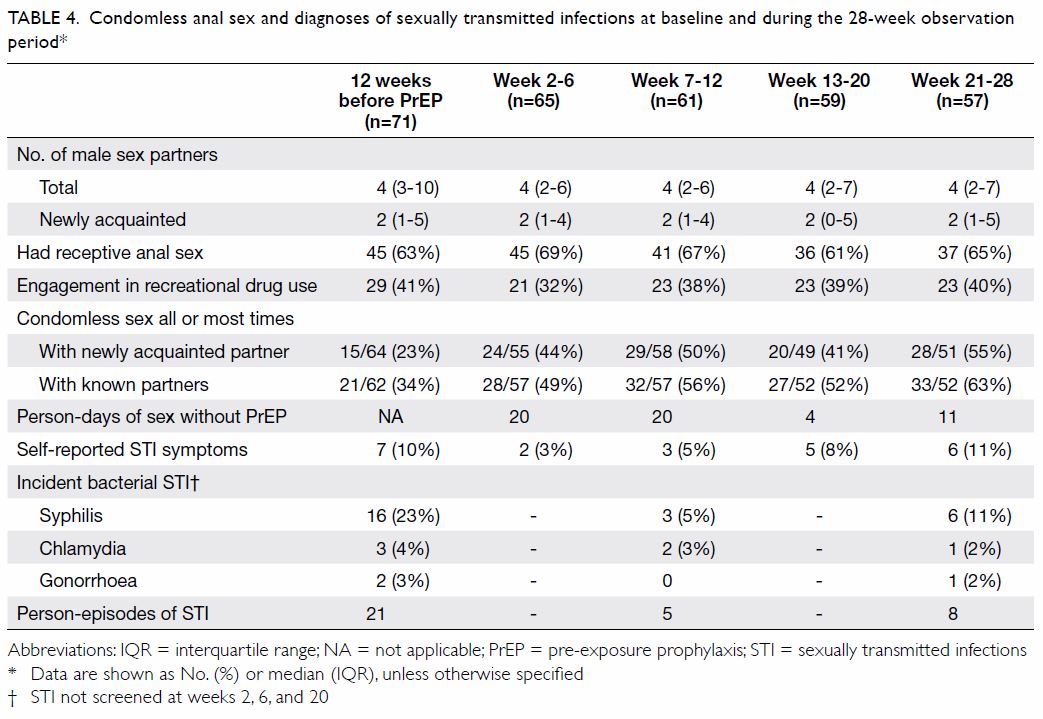

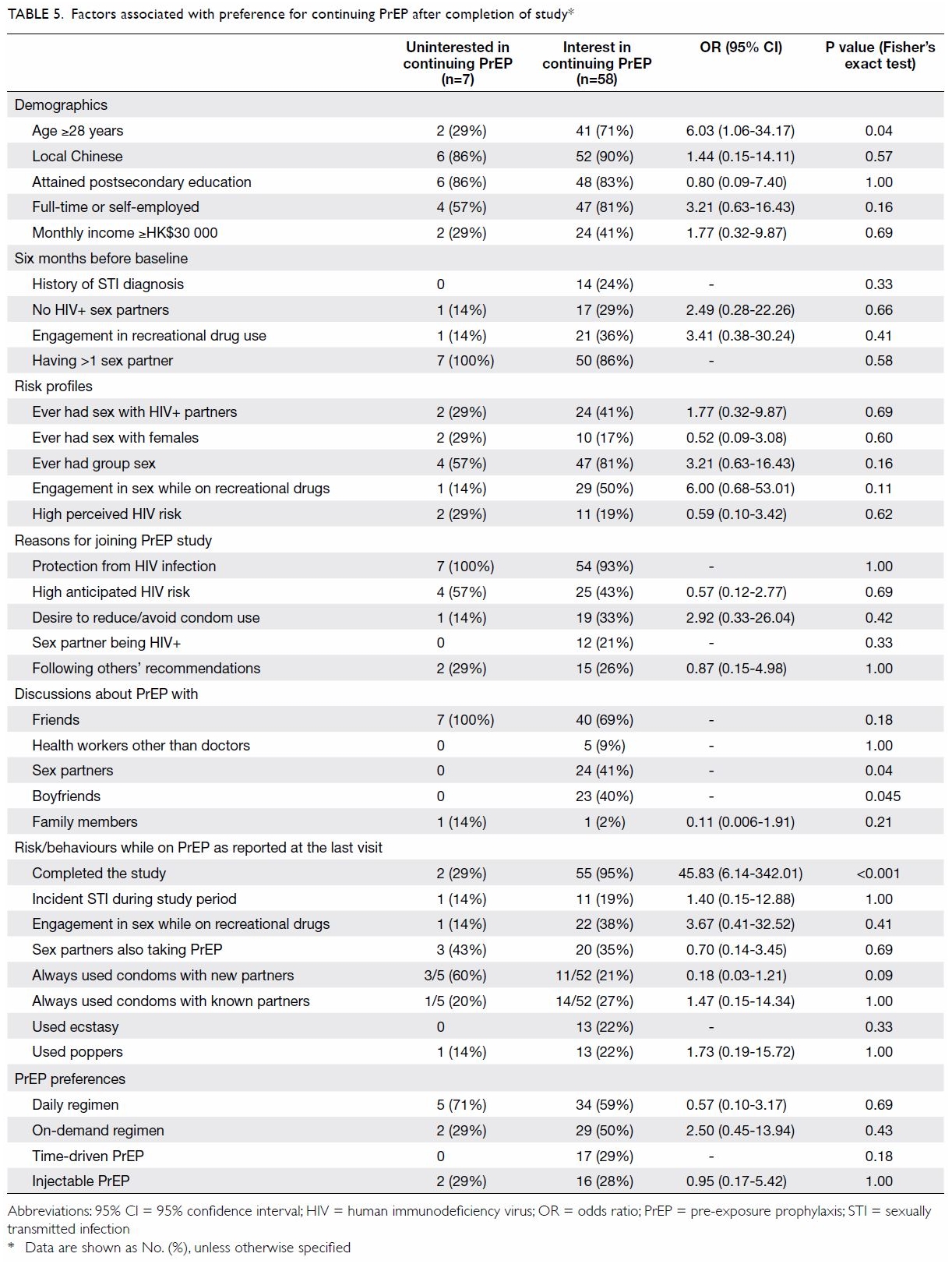

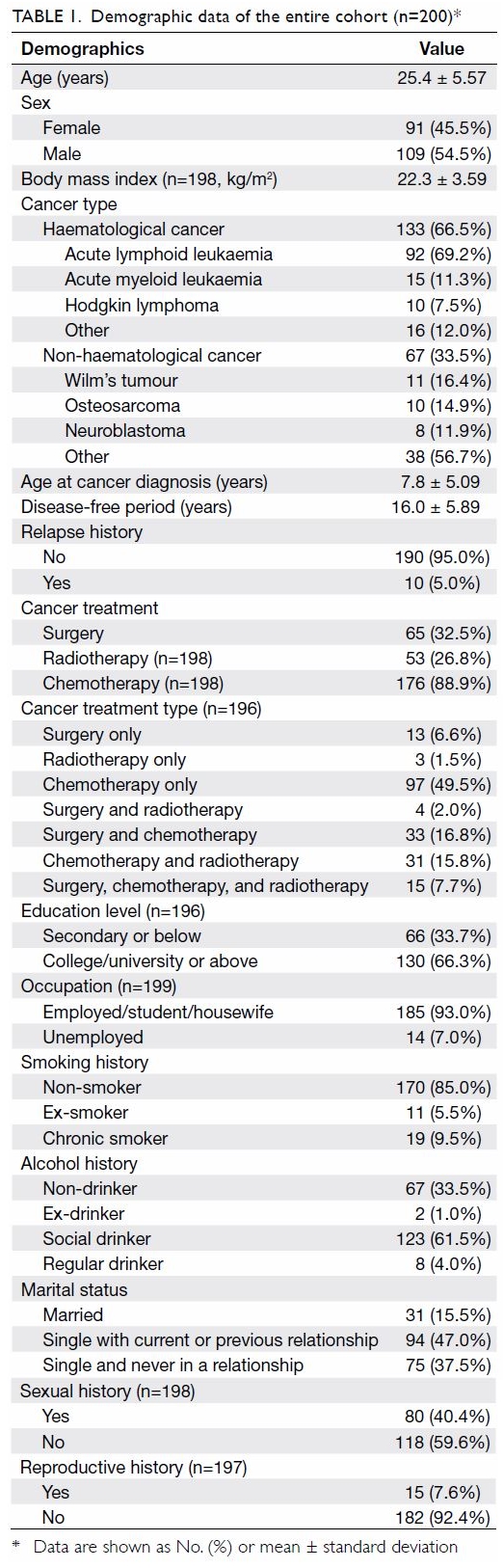

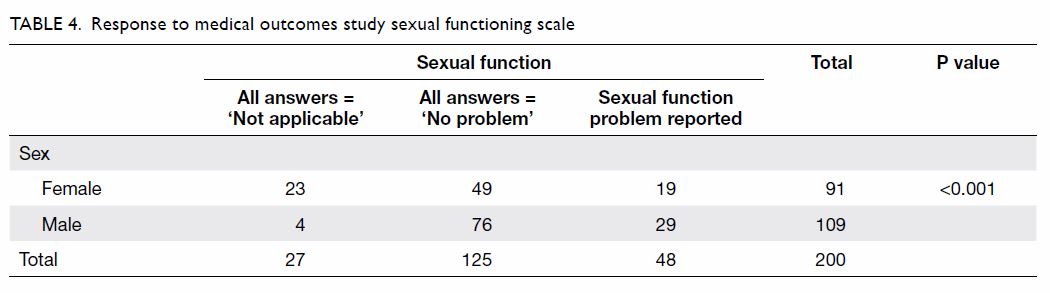

From October 2016 to August 2018, 66 new patients

attended our clinic for urological problems secondary to substance abuse.

After excluding patients with substance abuse other than ketamine and MA,

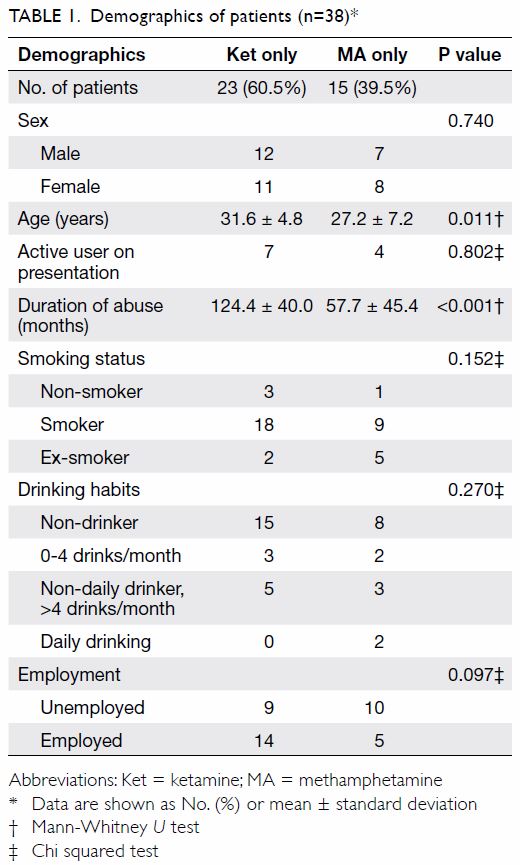

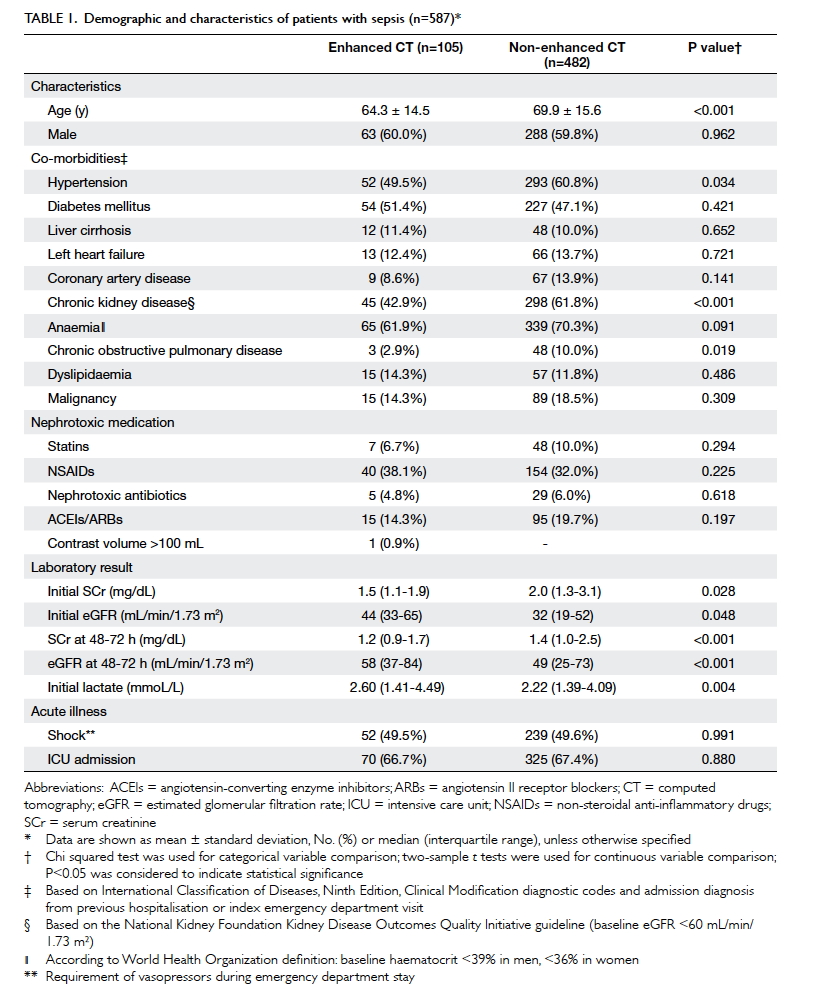

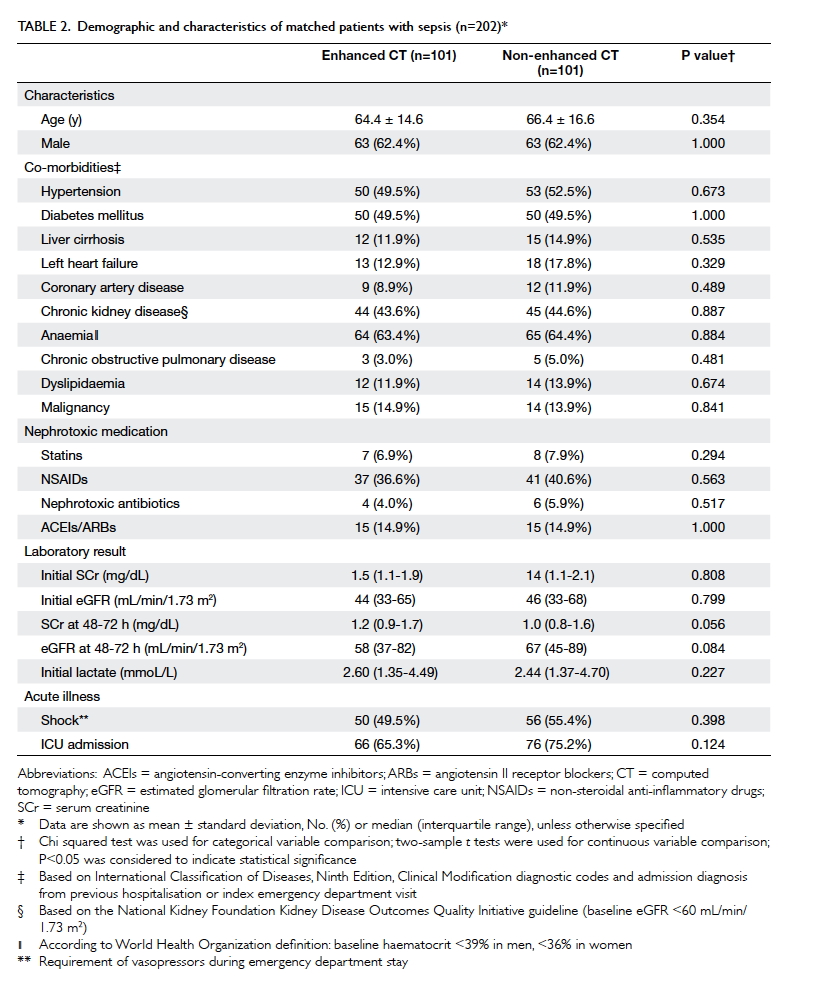

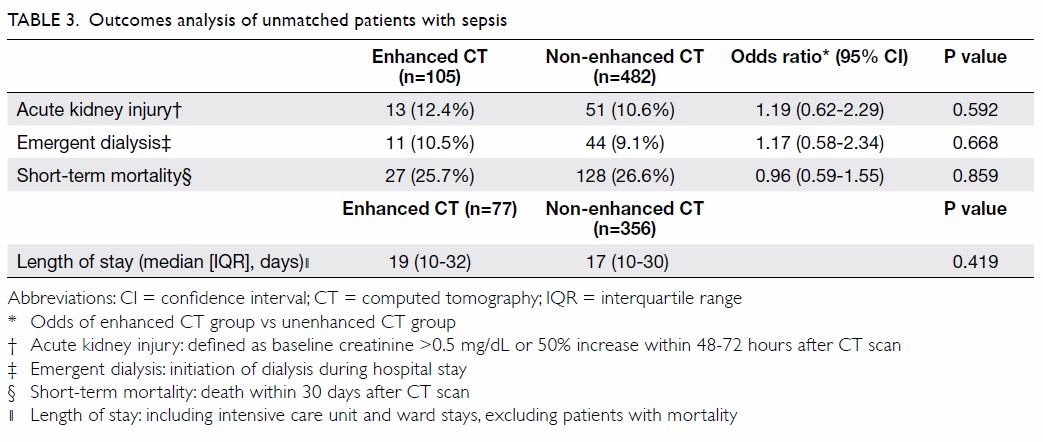

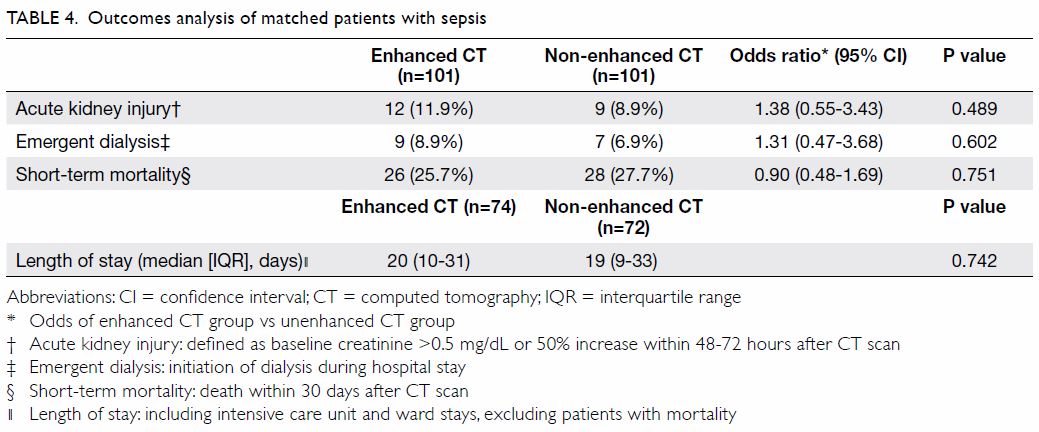

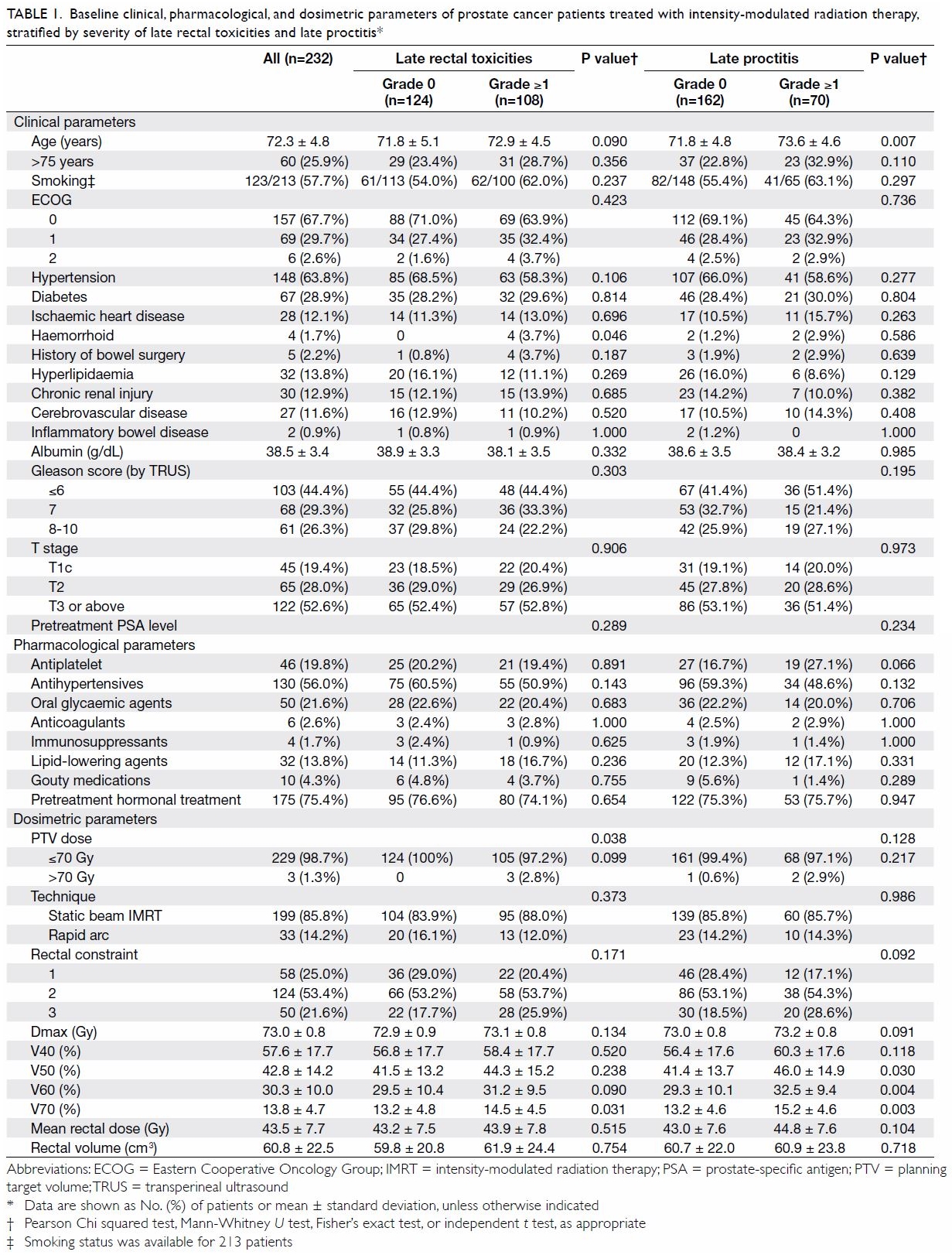

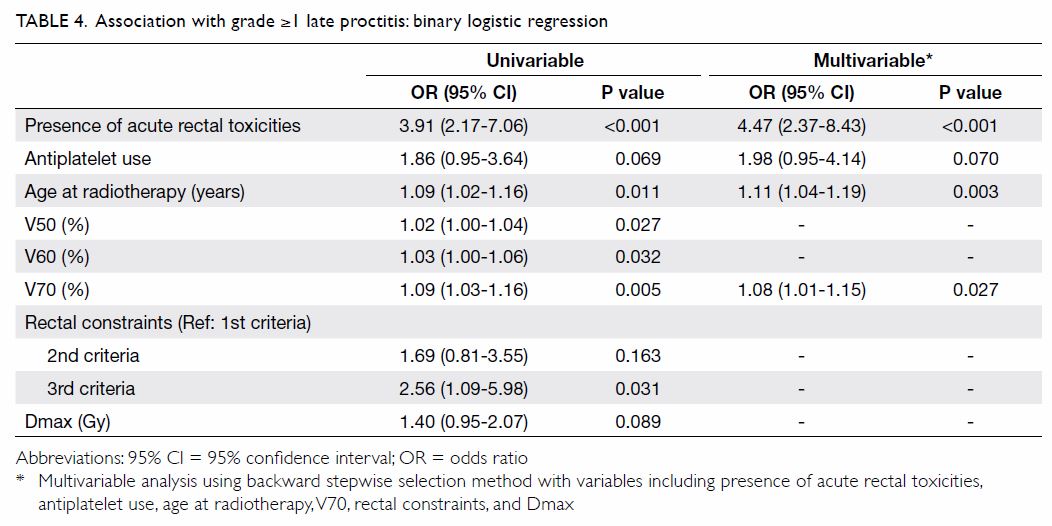

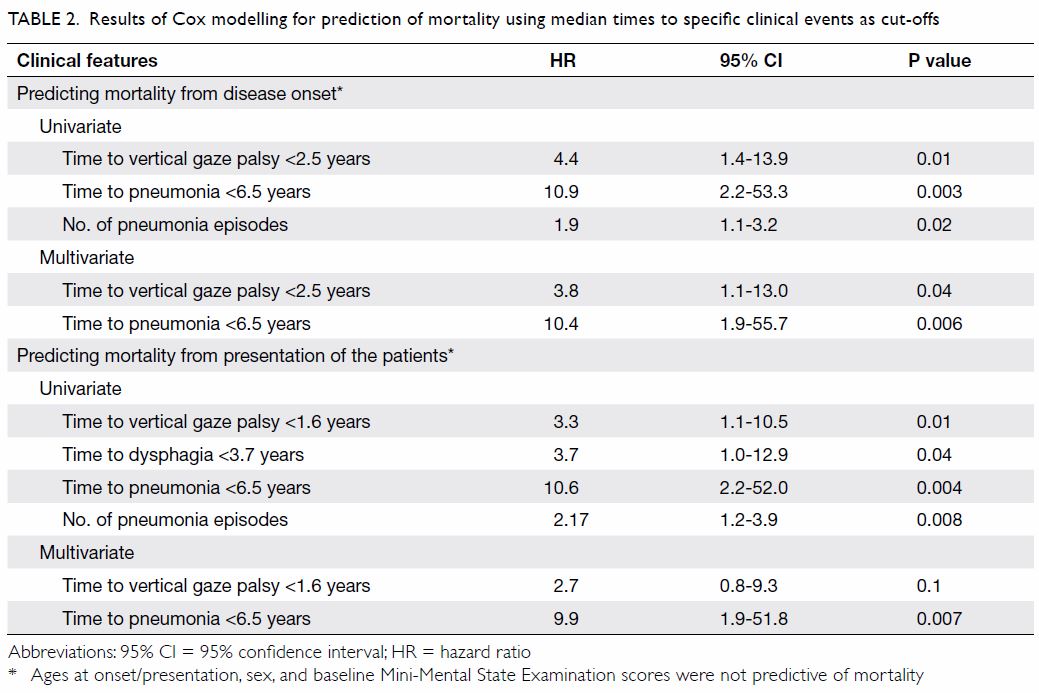

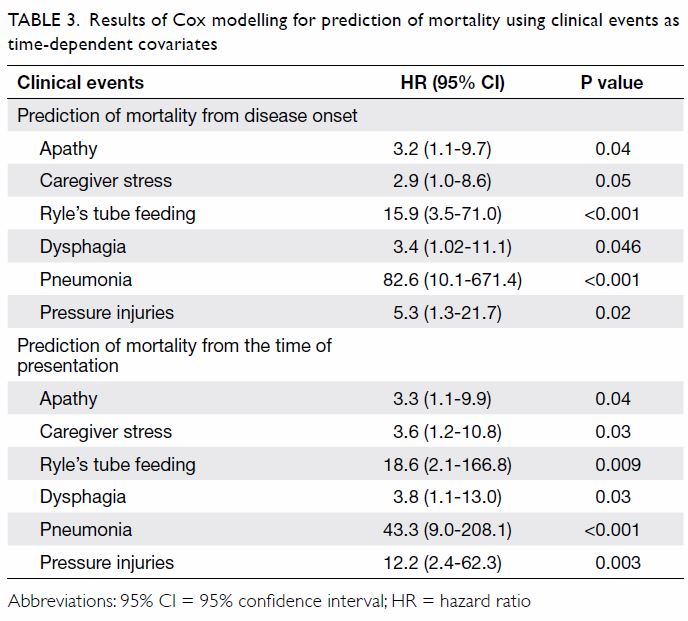

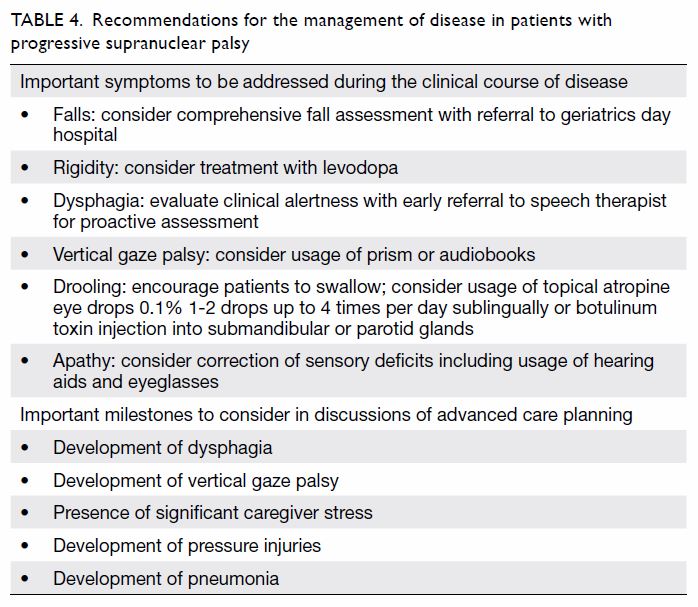

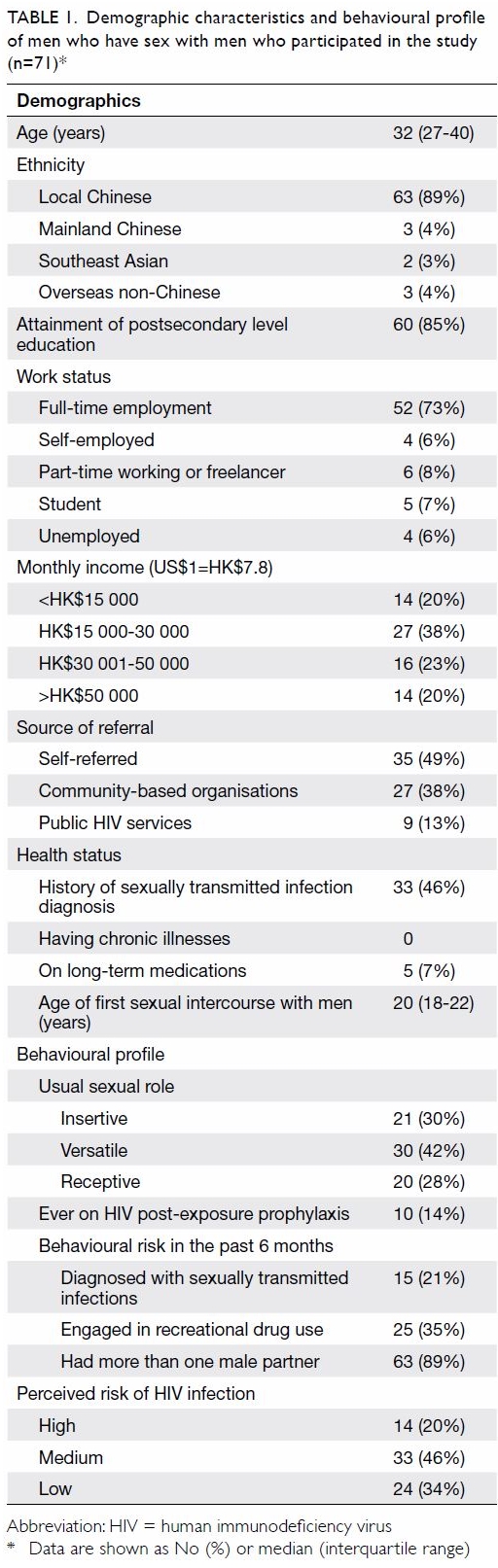

38 patients were included for analysis (Table 1). Both genders contributed 19 patients.

There was a statistically significant difference in mean age between the

two groups of patients with MA and ketamine abuse (27.2 ± 7.2 years and

31.6 ± 4.8 years, respectively, P=0.011). Most patients were not active

substance abusers upon presentation to the clinic. While all patients had

a history of substance abuse, only two (5.3%) patients were consuming

alcohol on a daily basis.

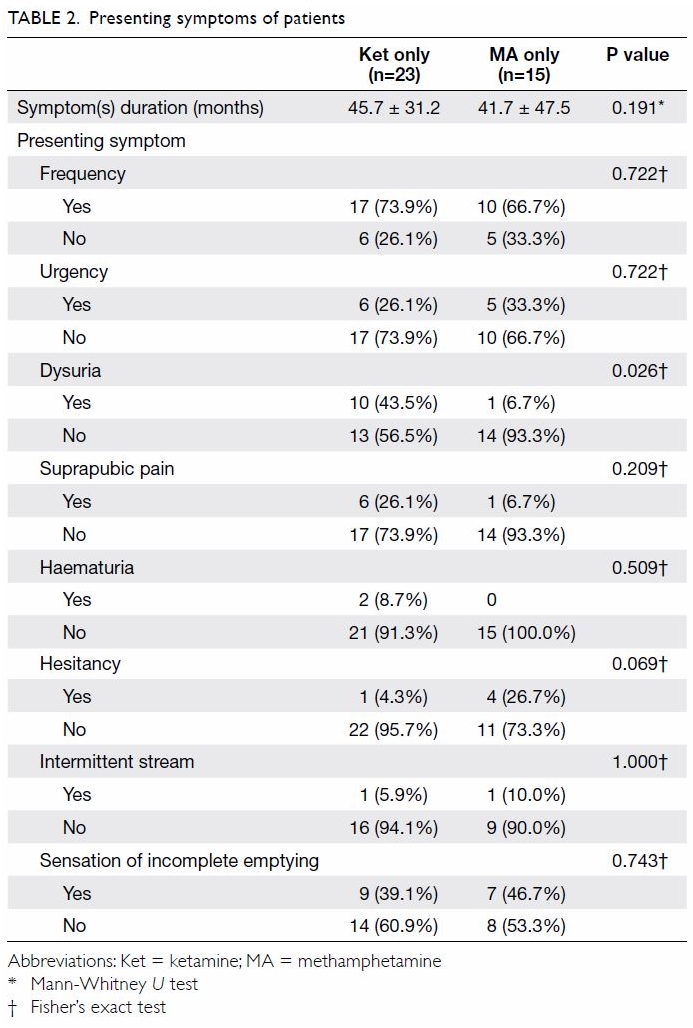

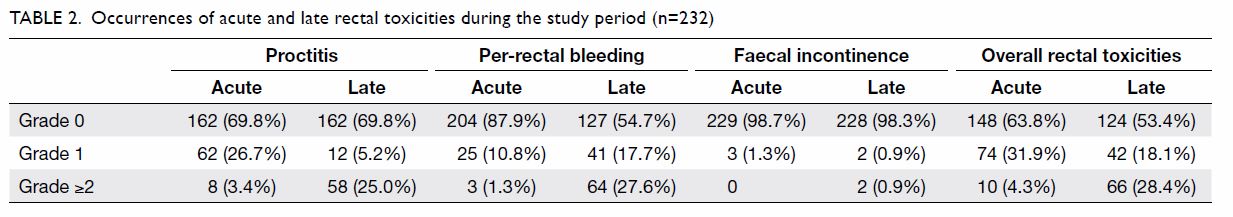

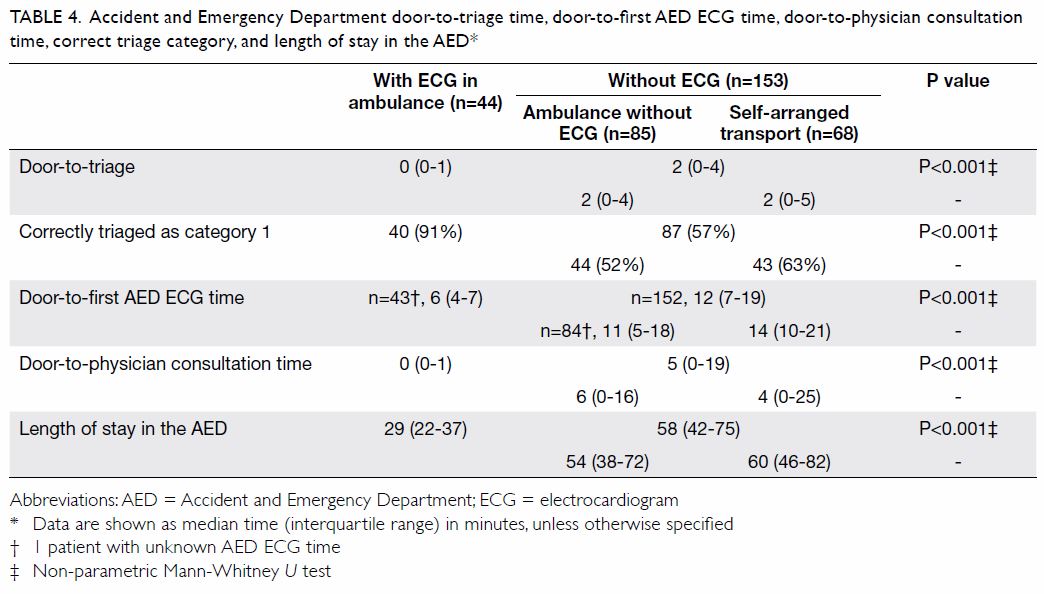

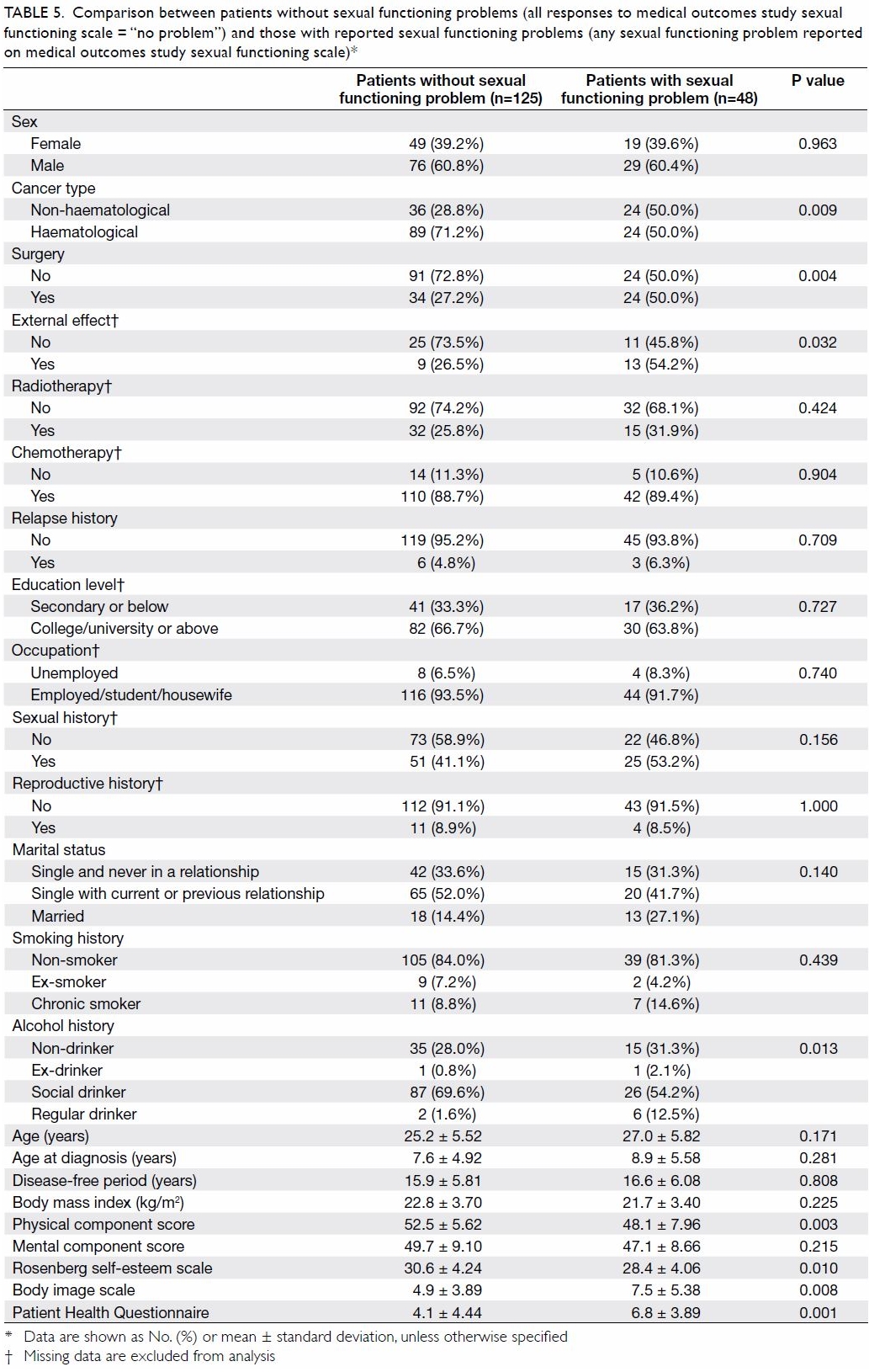

Urinary frequency was the single most common

urological symptom in our patient cohort. Regardless of whether the

patient was consuming ketamine alone, MA alone, or a combination of

ketamine and MA, urinary frequency was found in 71.1% of the patients,

with no statistically significant differences between these groups (Table

2). Other symptoms that shared similar distributions between both

groups were urgency, suprapubic pain, intermittent stream, and sensation

of incomplete emptying. There was a statistically significant difference

in the prevalence of dysuria between the two groups (ketamine 43.5%, MA

6.7%, P=0.026). A trend was observed in the difference in prevalence of

hesitancy (ketamine 4.3%, MA 26.7%, P=0.069).

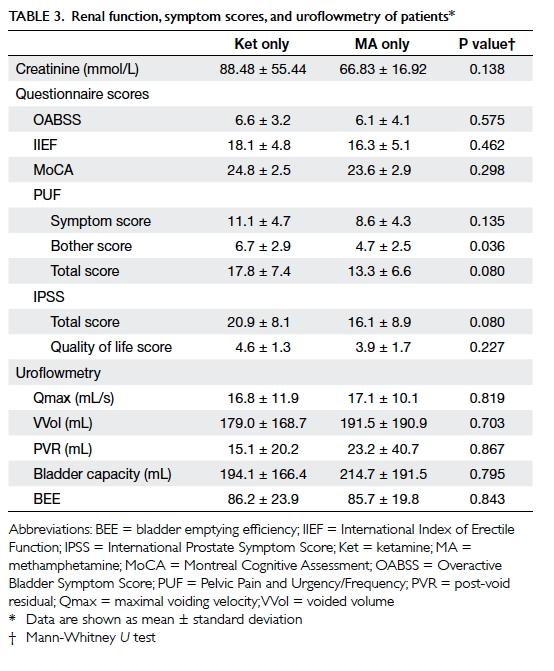

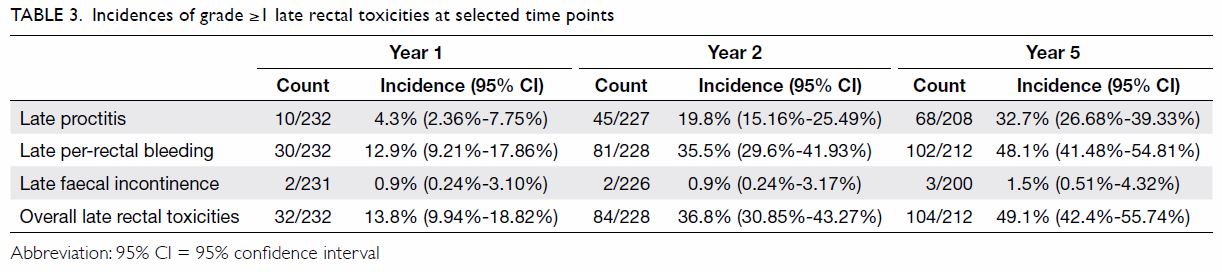

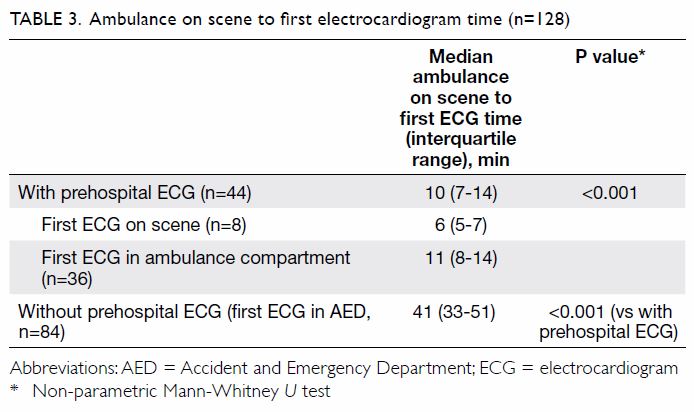

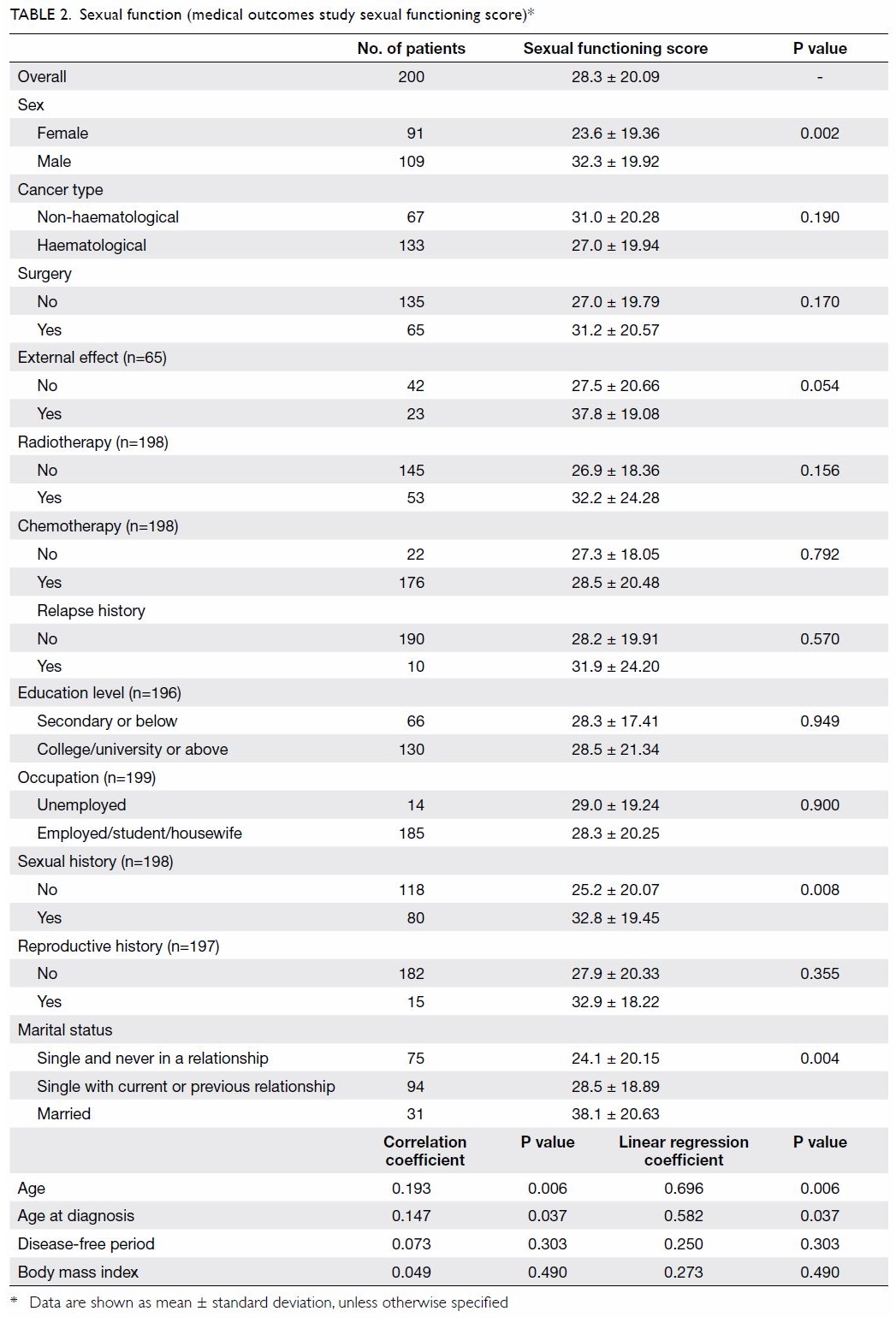

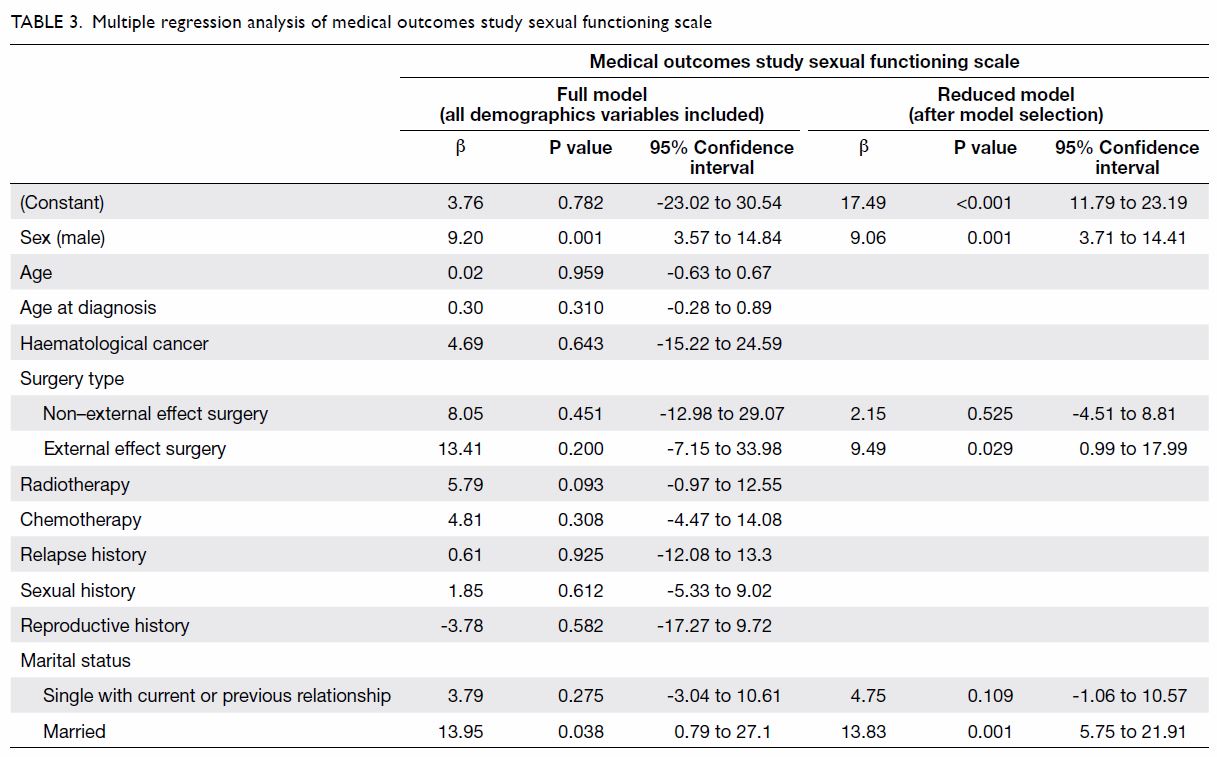

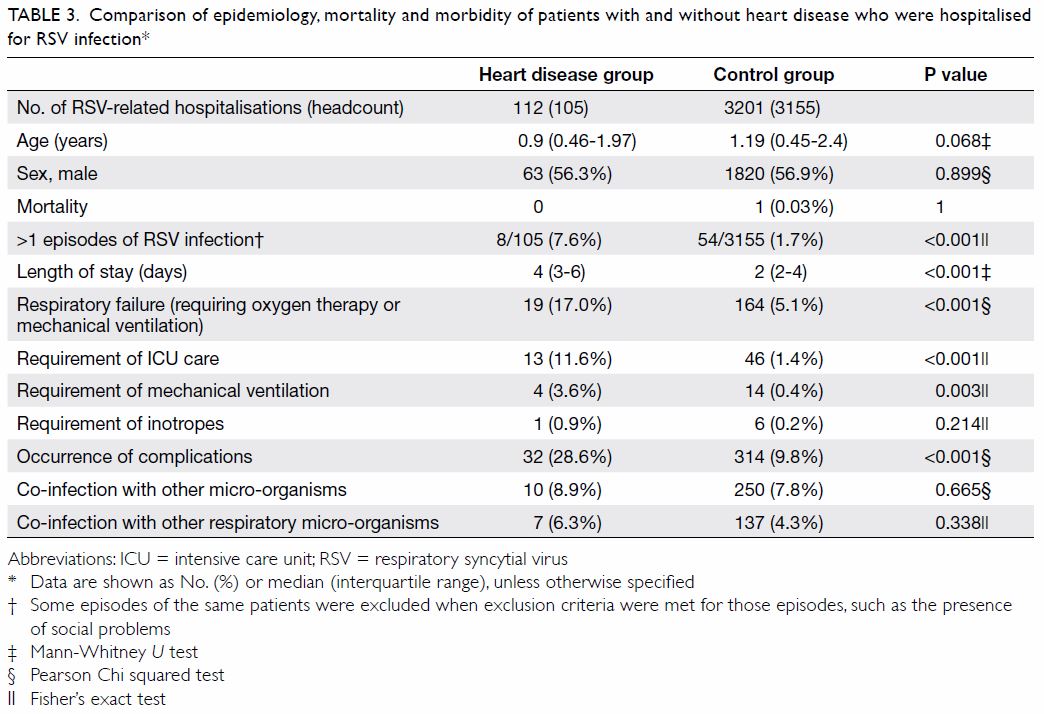

To summarise the results of questionnaires that

assess urinary storage symptoms and voiding symptoms as a whole, neither

OABSS nor IPSS revealed a statistically significant difference between the

two patient groups (Table 3). The mean IPSS score of the ketamine only

group was 20.9 ± 8.1, falling into the severe symptom category, whereas

that of the MA only group was 16.1 ± 8.9, falling into the moderate

symptom group. No significant differences in maximal voiding velocity,

voided volume, post-void residual, or bladder capacity were observed

between the two groups. Similarly, no significant difference was observed

in sexual function between the male patients of these three groups, as

assessed by IIEF.

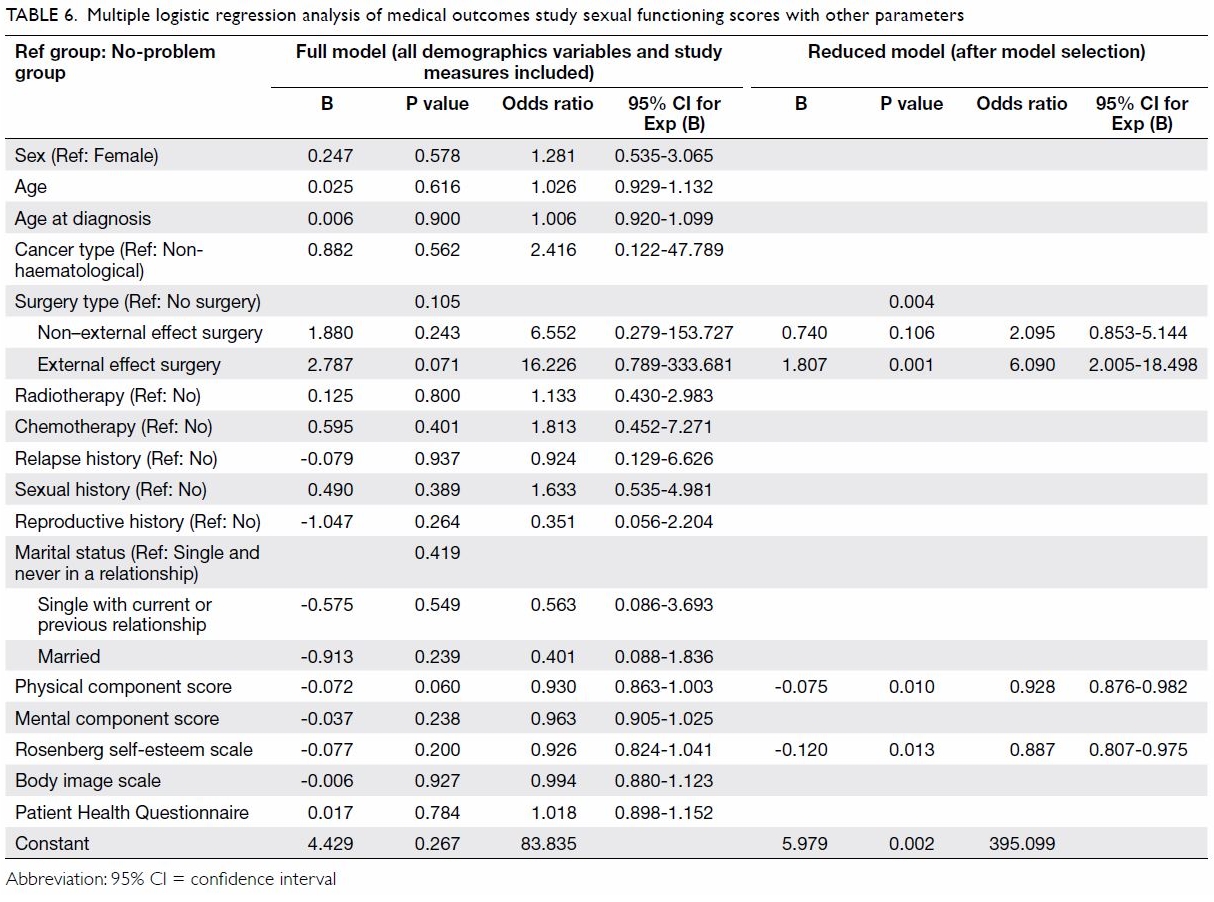

Pelvic pain assessment with the PUF symptom scale

revealed higher scores in the ketamine group, especially in the Bother

score domain (ketamine 6.7 ± 2.9, MA 4.7 ± 2.5, P=0.036). Cognitive

assessment using MoCA revealed that both groups had impairment, but there

was no significant difference between the MA group and the ketamine group

(ketamine 24.8 ± 2.5, MA 23.6 ± 2.9, P=0.298). Serum creatinine did not

differ significantly between the groups (ketamine 88.48 ± 55.44, MA 66.83

± 16.92, P=0.138).

Discussion

Substance abuse is a significant public health

problem, with approximately 5.2% of the world population aged between 15

and 64 years having used illicit drugs at least once in the previous year.1 Southeast and East Asia have been

a global hub for MA production and trafficking over the past decades, and

its abuse is common in areas of South Korea, China, Taiwan, Japan, the

Golden Triangle, and Iran.10

Psychotropic substance abuse is the most common form of drug abuse in Hong

Kong, and since 2015, MA has taken over ketamine’s spot as the leading

drug of abuse among all psychotropic substances.11

As MA has become the new trendy drug of abuse, and most drug abusers are

young and had their first drug exposure at an early age, this can account

for our finding that patients who used MA had a lower mean age than

patients who used ketamine in the cohort (Table 1).

Methamphetamine belongs to the class of

amphetamines that also includes other drugs such as MDMA

(3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine). The stimulant, euphoric,

anorectic, empathogenic, entactogenic, and hallucinogenic properties of MA

drive its popularity for abuse. Kolbrich et al15

demonstrated the fast, widespread, and long-lasting distribution of MA in

the human brain, paralleling the long-lasting behavioural and neurological

effects of the drug. Our data on cognitive impairment in MA users echoed

this finding, demonstrating impaired function in this group by MoCA

assessment.

Much of the focus on MA in the literature has been

placed on its neurological and behavioural aspects. Unlike ketamine, whose

effects on the urinary tract and treatment modalities have been more

commonly discussed,16 similar

research endeavours have not been undertaken in the area of MA, even

though it is a more widely abused drug. Thus, our study was an effort to

investigate the clinical presentation of MA abuse on the urinary tract and

compare it with ketamine abuse, another common drug of illicit use. As

illustrated by our findings in the cohort, patients who used MA reported

at least moderate severity of urinary symptoms by IPSS assessment. Because

we studied a group of young patients with mean age 27.2 years, we conclude

that the urological impact of MA abuse cannot be neglected.

In the current study, storage symptoms

(particularly urinary frequency) had similar prevalence between patients

who used MA and ketamine (Table 2). On assessment of storage symptoms by

OABSS, patients in both groups attained similar scores to patients with

overactive bladder syndrome.17 In

the case of ketamine abuse, storage symptoms can be attributed to denuded

mucosa and infiltration of inflammatory cells into the lamina propria of

the bladder, eventually leading to chronic inflammation and fibrosis.5 It has been postulated that the storage symptoms from

MA abuse can be the result of a dysfunctional dopamine pathway in detrusor

control. The β-phenylethylamine core structure of MA allows it to cross

the blood-brain barrier easily and to resist brain biotransformation.

Furthermore, its structural similarity with monoamine neurotransmitters

allows amphetamines to act as competitive substrates at dopamine’s

membrane transporters. It also promotes dopamine release from storage

vesicles. All these effects increase cytoplasmic dopamine concentrations

and enhance reverse transport.18

However, long-term exposure to amphetamines may result in dopamine neuron

terminal damage or loss. A post-mortem study of people who used MA

chronically showed a mean 50% to 60% reduction in dopamine levels

throughout the striatum.19 Another

study on dopamine dysregulation reported a 25% to 30% decrease in the

maximal extent of dopamine-induced stimulation of adenylyl cyclase

activity in the striatum.20 These

results suggested that dopamine signalling in the striatum of people who

use MA chronically was impaired both presynaptically and postsynaptically.

An animal study showed that a selective D1 antagonist decreased bladder

capacity in rats.21 Taking

Parkinson’s disease, which is the result of dopaminergic neuron

degeneration with the basal ganglia failing to suppress micturition,22 as a reference, the pathological dopaminergic pathway

could be one of the aetiologies behind MA-related urinary symptoms.

In our cohort, 26.7% of patients who used MA

reported hesitancy during voiding, and 46.7% reported a sensation of

incomplete emptying (Table 2). Case reports in the literature have drawn

an association between amphetamines and urinary retention.23 24 These

findings underlined the possibility that MA-related urological pathology

might have multiple facets rather than purely concerning the dopaminergic

axis and storage symptoms. The possible aetiology may be the increased

release of norepinephrine from MA abuse, which may cause increased

α-adrenergic stimulation of the bladder neck.25

In a study of medical treatment for urinary symptoms in people who used

MA, Koo et al26 reported that

α-blockers resulted in a 33% treatment success rate in terms of IPSS

reduction for patients with predominant voiding symptoms. This observation

could be employed as a reference for treatment options.

Patients with ketamine abuse more commonly

experienced dysuria and pelvic pain. In our previous report of 319

patients with ketamine abuse, the mean PUF score was 22.2.16 In contrast, symptoms of dysuria and pelvic pain were

not commonly observed in patients with MA abuse. This could be because the

effects of MA on the urinary tract were more on neurology rather than

local tissue destruction, resulting in less local nociceptor stimulation.

Currently, there are no reports on histological assessment of urinary

tract tissues in people who use MA. This would be useful to facilitate a

more comprehensive investigation on the impact on MA on the urinary tract.

The relatively small sample size of our cohort

limited our statistical analysis. As MA abuse has only gained popularity

in recent years in our locality, and the urological sequelae of such abuse

might take years before it becomes prominent and severe, the current study

could act as an initial assessment highlighting the early observation of

urological presentation. One of the potential limitations of our study is

that the majority of the patients presenting to our clinic were not active

substance abusers. At the time point of assessment, the use of a

heterogeneous group of active and former abusers may introduce bias into

our evaluation. However, our cohort included mostly patients with long

abuse duration. Studies have demonstrated the persistent effects of drug

abuse even after a period of abstinence, namely dysfunctional dopamine

metabolism in patients who had used MA27

and urinary tract damage in patients who had used ketamine.5 Thus, the clinical picture captured by our study may

still reflect the impact of drug abuse on the urinary tract.

In conclusion, MA is a common drug of choice for

abuse in Asia. It causes urinary tract dysfunction, predominantly in the

form of storage symptoms. Compared with ketamine, MA abuse was not

commonly associated with dysuria or pelvic pain. In addition to the

behavioural impacts of MA abuse, its urinary tract implications should not

be neglected.

Author contributions

All authors had full access to the data,

contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and

take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Concept or design: CH Yee, CF Ng, YH Tam.

Acquisition of data: YL Hong, PT Lai.

Analysis or interpretation of data: CH Yee, YL Hong.

Drafting of the article: CH Yee, YL Hong.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: CH Yee, CF Ng, YH Tam.

Acquisition of data: YL Hong, PT Lai.

Analysis or interpretation of data: CH Yee, YL Hong.

Drafting of the article: CH Yee, YL Hong.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: CH Yee, CF Ng, YH Tam.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, CF Ng was not involved

in the peer review process of the article. Other authors have no conflicts

of interest to disclose.

Funding/support

This research project was funded by the Beat Drugs

Fund, The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

Ethics approval

Ethics committee approval was granted for the study

(CREC Ref CRE-2011.454). Written informed consent was given by all

participants before entering the study.

References

1. United Nations Office on Drugs and

Crime. World drug report. 2018. Available from:

https://www.unodc.org/wdr2018/. Accessed 10 May 2019.

2. Chacko JA, Heiner JG, Siu W, Macy M,

Terris MK. Association between marijuana use and transitional cell

carcinoma. Urology 2006;67:100-4. Crossref

3. Bowles DW, O’Bryant CL, Camidge DR,

Jimeno A. The intersection between cannabis and cancer in the United

States. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2012;83:1-10. Crossref

4. Madhrira MM, Mohan S, Markowitz GS,

Pogue VA, Cheng JT. Acute bilateral renal infarction secondary to

cocaine-induced vasospasm. Kidney Int 2009;76:576-80. Crossref

5. Yee C, Ma WK, Ng CF, Chu SK.

Ketamine-associated uropathy: from presentation to management. Curr

Bladder Dysfunct Rep 2016;11:266-71. Crossref

6. Yiu-Cheung C. Acute and chronic toxicity

pattern in ketamine abusers in Hong Kong. J Med Toxicol 2012;8:267-70. Crossref

7. Ren Q, Ma M, Hashimoto K. Current status

of substance abuse in East Asia and therapeutic prospects. East Asian Arch

Psychiatry 2016;26:45-51.

8. Sun HQ, Bao YP, Zhou SJ, Meng SQ, Lu L.

The new pattern of drug abuse in China. Curr Opin Psychiatry

2014;27:251-5. Crossref

9. Wada K, Funada M, Shimane T. Current

status of substance abuse and HIV infection in Japan. J Food Drug Anal

2013;21:S33-6. Crossref

10. Kwon NJ, Han E. A commentary on the

effects of methamphetamine and the status of methamphetamine abuse among

youths in South Korea, Japan, and China. Forensic Sci Int 2018;286:81-5. Crossref

11. Narcotics Division, Security Bureau,

Hong Kong SAR Government. Central Registry of Drug Abuse Sixty-Seventh

Report. Available from: https://www.nd.gov.hk/en/crda_report.htm. Accessed

10 May 2019.

12. Homma Y, Yoshida M, Seki N, et al.

Symptom assessment tool for overactive bladder syndrome–overactive bladder

symptom score. Urology 2006;68:318-23. Crossref

13. Ng CM, Ma WK, To KC, Yiu MK. The

Chinese version of the Pelvic Pain and Urgency/Frequency Symptom Scale: a

useful assessment tool for street-ketamine abusers with lower urinary

tract symptoms. Hong Kong Med J 2012;18:123-30.

14. Chu LW, Ng KH, Law AC, Lee AM, Kwan F.

Validity of the Cantonese Chinese Montreal Cognitive Assessment in

Southern Chinese. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2015;15:96-103. Crossref

15. Kolbrich EA, Goodwin RS, Gorelick DA,

Hayes RJ, Stein EA, Huestis MA. Plasma pharmacokinetics of

3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine after controlled oral administration to

young adults. Ther Drug Monit 2008;30:320-32. Crossref

16. Yee CH, Lai PT, Lee WM, Tam YH, Ng CF.

Clinical outcome of a prospective case series of patients with ketamine

cystitis who underwent standardized treatment protocol. Urology

2015;86:236-43. Crossref

17. Hung MJ, Chou CL, Yen TW, et al.

Development and validation of the Chinese Overactive Bladder Symptom Score

for assessing overactive bladder syndrome in a RESORT study. J Formos Med

Assoc 2013;112:276-82. Crossref

18. Carvalho M, Carmo H, Costa VM, et al.

Toxicity of amphetamines: an update. Arch Toxicol 2012;86:1167-231. Crossref

19. Wilson JM, Kalasinsky KS, Levey AI, et

al. Striatal dopamine nerve terminal markers in human, chronic

methamphetamine users. Nat Med 1996;2:699-703. Crossref

20. Tong J, Ross BM, Schmunk GA, et al.

Decreased striatal dopamine D1 receptor-stimulated adenylyl cyclase

activity in human methamphetamine users. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:896-903.

Crossref

21. Seki S, Igawa Y, Kaidoh K, Ishizuka O,

Nishizawa O, Andersson KE. Role of dopamine D1 and D2 receptors in the

micturition reflex in conscious rats. Neurourol Urodyn 2001;20:105-13. Crossref

22. McDonald C, Winge K, Burn DJ. Lower

urinary tract symptoms in Parkinson’s disease: prevalence, aetiology and

management. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2017;35:8-16. Crossref

23. Worsey J, Goble NM, Stott M, Smith PJ.

Bladder outflow obstruction secondary to intravenous amphetamine abuse. Br

J Urol 1989;64:320-1. Crossref

24. Delgado JH, Caruso MJ, Waksman JC,

Honigman B, Stillman D. Acute, transient urinary retention from combined

ecstasy and methamphetamine use. J Emerg Med 2004;26:173-5. Crossref

25. Skeldon SC, Goldenberg SL. Urological

complications of illicit drug use. Nat Rev Urol 2014;11:169-77. Crossref

26. Koo KC, Lee DH, Kim JH, et al.

Prevalence and management of lower urinary tract symptoms in

methamphetamine abusers: an under-recognized clinical identity. J Urol

2014;191:722-6. Crossref

27. Ares-Santos S, Granado N, Moratalla R.

The role of dopamine receptors in the neurotoxicity of methamphetamine. J

Intern Med 2013;273:437-53. Crossref