Hong

Kong Med J 2018 Dec;24(6):571–8 | Epub 14 Nov 2018

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj177149

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Cross-sectional study on emergency department

management of sepsis

Kevin KC Hung, FHKCEM, MPH1,2; Rex PK

Lam, FHKCEM, MPH3; Ronson SL Lo, MB, BCh, BAO1;

Justin W Tenney, PharmD, BCPS4; Marc LC Yang, FHKCEM1,5;

Marcus CK Tai, FHKCEM1,2; Colin A Graham, FHKCEM, MD1,2

1 Accident and Emergency Medicine

Academic Unit, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

2 Accident and Emergency Department,

Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

3 Emergency Medicine Unit, The

University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

4 School of Pharmacy, The Chinese

University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

5 Accident and Emergency Department,

Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Jordan, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof Colin A Graham (cagraham@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Emergency

departments (EDs) play an important role in the early identification and

management of sepsis. Little is known about local EDs’ processes of care

for sepsis, adoption of international recommendations, and the impact of

the new Sepsis-3 definitions.

Methods: Structured telephone

interviews based on the United Kingdom Sepsis Trust ‘Exemplar Standards

for the Emergency Management of Sepsis’ were conducted from January to

August 2017 with nominated representatives of all responding public

hospital EDs in Hong Kong, followed by a review of hospital/departmental

sepsis guidelines by the investigators.

Results: Sixteen of the 18

public EDs in Hong Kong participated in the study. Among various

time-critical medical emergencies such as major trauma, sepsis was

perceived by the interviewees to be the leading cause of in-hospital

mortality and the second most important preventable cause of death.

However, only seven EDs reported having departmental guidelines on

sepsis care, with four adopting the Quick Sequential Organ Failure

Assessment score or its modified versions. All responding EDs reported

that antibiotics were stocked within their departments, and all EDs with

sepsis guidelines mandated early intravenous antibiotic administration

within 1 to 2 hours of detection. Reported major barriers to optimal

sepsis care included lack of knowledge and experience, nursing human

resources shortages, and difficulty identifying patients with sepsis in

the ED setting.

Conclusion: There are

considerable variations in sepsis care among EDs in Hong Kong. More

training, resources, and research efforts should be directed to early ED

sepsis care, to improve patient outcomes.

New knowledge added by this study

- Large variations were found in practice and adoption of international sepsis recommendations across emergency departments (EDs) in Hong Kong. Fewer than half of the EDs had sepsis management guidelines, and there were no regular audits or any registry to monitor the performance of sepsis care.

- Although sepsis was perceived as the leading cause of in-hospital mortality, and second only to trauma in terms of preventable mortality, sepsis has not received a high level of attention within EDs.

- Many EDs specified the requirements for early intravenous antibiotics administration and stocked antibiotics, but they differed in terms of the methods and screening criteria used for identification of patients with sepsis.

- Sepsis, an emergency condition with high mortality that requires timely intervention, continues to lack adequate attention and resource allocation within EDs in Hong Kong. Now is a critical time to review whether performance indicators for sepsis should be formalised.

- Previous sporadic quality improvement programmes were not adequate to address the high mortality of patients with sepsis who attend EDs. Sustained improvements in resources and training must be provided to improve care for patients with sepsis in Hong Kong.

- By overcoming barriers including the lack of knowledge among ED staff and the need for standard screening to be implemented, EDs in Hong Kong have the capacity to provide a higher standard of care for sepsis patients.

Introduction

The global incidence rates of hospital-treated

sepsis and severe sepsis have been estimated as 437 and 270 cases per 100

000 person years, respectively,1

accounting for 17% and 26% of hospital mortality, respectively. The same

study estimated that 31.5 million cases of sepsis and 19.4 million cases

of severe sepsis account for 5.3 million deaths annually worldwide.1 The ageing of the population and the increasing number

of people living with co-morbid conditions are believed to be important

factors associated with the increasing incidence of sepsis.2

In early 2016, sepsis was re-defined as

‘life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response

to infection’ (Sepsis-3).3 The

criteria used for identifying patients with sepsis were also updated, with

the removal of the original systemic inflammatory response syndrome

criteria that had been used since the early 1990s. The Sequential Organ

Failure Assessment (SOFA) score is commonly used in intensive care units

(ICUs) for assessment of organ dysfunction. The quickSOFA (qSOFA) score

has been proposed as a bedside screening tool for patients at risk of

sepsis with adverse outcomes in emergency departments (EDs) and other

non-ICU settings. The evidence base for such a proposal is accumulating,4 and the optimal screening tool for

sepsis in EDs has not yet been identified.5

6 7

8

The recent ProCESS,9

ProMISE,10 and ARISE trials11 confirmed the importance of early recognition with

fluid resuscitation and appropriate antibiotic therapy in improving sepsis

outcomes. These trials refuted the need for strict adherence to the

haemodynamic goals proposed by Rivers et al in 2001 as early goal-directed

therapy.12 Although it is

generally agreed that early initiation of therapy is key to surviving

sepsis, controversies remain regarding the initial rate and choice of

fluids, the role and choice of inotropes, the identification of infection

sources with imaging and other techniques, the use of appropriate

antibiotics, and the optimal microbiological workup.13 14 15 16 17

The ED occupies a critical position in a patient’s

journey of sepsis care and plays an important role in the early

identification and treatment of sepsis.17

Despite frequent encounters with sepsis in EDs, few studies in Hong Kong

have investigated sepsis care. Yang et al18

studied patients with sepsis and septic shock in a tertiary university

teaching hospital and found no significant change in the in-hospital

mortality rate after the implementation of sepsis guidelines

(pre-implementation: 29.6% in 2009; post-implementation: 35.3% in 2010).

Although a significant proportion (25.5% in 2009 and 40.2% in 2010) of the

recruited patients had hypoperfusion (mean arterial pressure <65 mm Hg

or lactate >4 mmol/L), only 10.4% to 11.8% had blood cultures drawn,

13.0% to 23.5% had antibiotics administered, and 24.5% to 29.6% had fluid

resuscitation initiated in the ED. In that study, sepsis was recognised in

the ED in only two-thirds of the patients with sepsis who presented there.

Tse et al19 reported similar

findings in their study on the impact of departmental sepsis guidelines on

mortality (pre-implementation mortality: 25.8%; post-implementation

mortality: 33%), although there were improved rates of blood culture

collection and antibiotic administration in the ED after its

implementation. Overall, 17.2% of patients required direct ICU admission.

Those studies highlighted a few important issues

regarding sepsis care in Hong Kong EDs: a heavy burden of sepsis, low

compliance with treatment guidelines, and poor patient outcomes despite

efforts to standardise care. Evidently, implementing sepsis guidelines is

insufficient, and there is a need to evaluate the whole process of care

systematically. Moreover, those previous studies involved only individual

EDs and, thus, might not be representative of other EDs. Furthermore, the

adoption of international recommendations about sepsis care and the impact

of the new Sepsis-3 definitions on ED practice are not known. We therefore

conducted a survey to evaluate the process of sepsis care, the uptake of

international recommendations and the Sepsis-3 definitions to departmental

sepsis guidelines, and the barriers faced by health care providers in

public EDs in Hong Kong.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional survey across all EDs in

Hong Kong in 2017. All 18 public EDs under the Hospital Authority were

invited to participate. Private EDs and 24-hour out-patient departments

were excluded because 90% of in-patient care is provided by public

hospitals in Hong Kong. One representative was nominated by the Chief of

Service (medical director) of each ED to speak on behalf of the

department, but not individuals. The telephone survey was based on an

interview guide provided before the interview (online supplementary Appendix).

Interview guide development

The interview guide was developed by the study team

with the structure recommended by the UK Sepsis Trust “Exemplar Standards

for the Emergency Management of Sepsis”.20

It included nine domains: departmental guidelines on sepsis, screening

criteria for sepsis, physical location and resources, sepsis care and

microbiology, antibiotics availability and antimicrobial guidelines,

support from ICU and other departments, factors affecting the level of

care provided, priority of audits and research, and training and quality

assurance.

Telephone interview

One investigator (KH) performed all of the

telephone interviews from January to August 2017. Email invitations were

sent to the Chiefs of Services of all 18 departments 2 to 3 weeks before

the telephone interviews, and all participating departments were asked to

provide their prevailing sepsis guidelines (if available) before the

telephone interviews. Departments that had not responded were contacted

again up to a total of 4 times.

Data analysis

All telephone interviews were audio recorded after

obtaining consent. Interview data were recorded using a standardised data

collection sheet, and data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet.

Descriptive statistics were presented as medians for continuous variables

(unless specified otherwise) and percentage proportions for categorical

variables. Participants ranked each of the nine barriers to sepsis care

using a 5-point Likert scale (‘not important’ 1; ‘slightly important’ 2;

‘important’ 3; ‘fairy important’ 4; and ‘very important’ 5).

Results

Out of the 18 EDs, 16 agreed to participate. One

department declined to participate, and one did not respond after repeated

contacts.

Departmental guidelines on sepsis

Seven departments reported the presence of sepsis

guidelines in their EDs, with three of these departments using the same

regional guidelines. Therefore, five different sets of sepsis guidelines

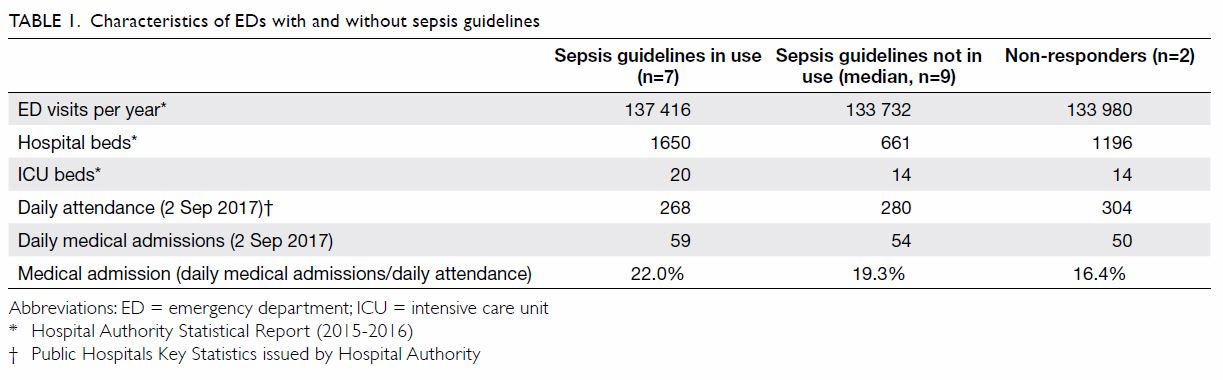

were reported to be in current use across all public EDs in Hong Kong. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the EDs with

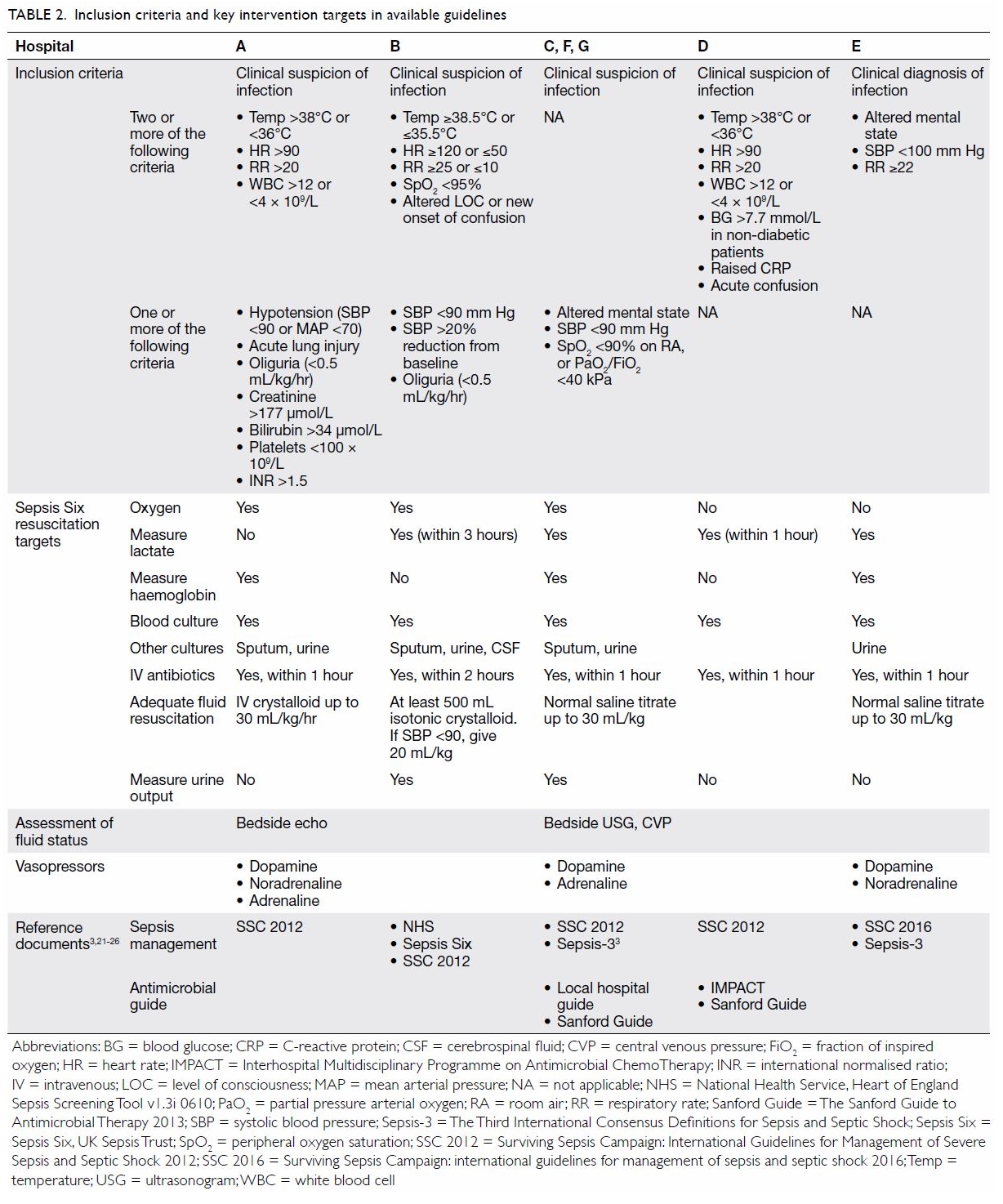

and without sepsis guidelines. Table 23 21 22

23 24

25 26

summarises the core components of the five sets of guidelines reported.

Most of the current versions of the guidelines were implemented between

2014 and 2017.

Screening criteria for sepsis

Four out of the seven departments with sepsis

guidelines used qSOFA, which is based on the Sepsis-3 recommendations.

Three departments (which used the same regional guidelines) used modified

qSOFA criteria. The reasons for this, as reported by respondents, included

the concern that replacing the definition of ‘severe sepsis’ with a qSOFA

score might increase the number of cases screened as positive. This would

result in an increased number of cases requiring management in

resuscitation rooms and put further strain on the already scarce ED human

resources.

The use of lactate as a biomarker for clinical

decision making in sepsis care was uncommon in the surveyed EDs. Fourteen

out of the 16 EDs had access to point-of-care testing of blood gases

inside the department, but only five had a lactate module. The ED

physicians mainly rely on patients’ vital signs and clinical assessment to

facilitate recognition of sepsis.

Physical location and resources

Upon identification of sepsis, two of the EDs’

guidelines explicitly mentioned sending the patient to a resuscitation

room (or a bed with intensive monitoring, eg, a high-dependency unit).

Most of the surveyed EDs (13 of 16) routinely managed patients with sepsis

in their resuscitation rooms. None of the EDs had a designated team or a

code specifically for patients with sepsis, unlike the management of major

trauma, for which the EDs employed a trauma team approach. One of the EDs

had designed a sepsis kit consisting of antiseptic swab sticks and pre-set

blood collection tubes and had investigation shortcuts in the computer

system to facilitate implementation of the guidelines.

Sepsis care and microbiology

Regarding the resuscitation and stabilisation of

patients with sepsis, Table 2 highlights the key areas covered by the

existing guidelines. All sets of guidelines refer to the Surviving Sepsis

Campaign targets21 22 or the UK Sepsis Six targets.23 All sets of guidelines also mention time to

intravenous antibiotics and microbiological workup, including blood

cultures, with the majority specifying intravenous antibiotics within 1

hour of the patient’s arrival.

Most EDs (13 of 16) expressed a preference to use

normal saline or other isotonic crystalloids for fluid resuscitation. The

target volume is up to 20 to 30 mL/kg, with monitoring of the patient’s

blood pressure (especially mean arterial pressure) for fluid

responsiveness. The use of ultrasonograms was reported to be increasing,

especially bedside echocardiograms and inferior vena cava variability, to

assess patients’ fluid status. Central venous pressure was mentioned, but

its use by ED physicians was perceived to be decreasing in frequency. If

vasopressors or inotropes were needed, dopamine was the most common

choice, as it can be administered via peripheral veins.

Concerning source identification for sepsis, most

sets of guidelines (4 of 5) mentioned chest X-rays and urinalysis. If

abdominal sepsis was suspected, some EDs would consult their surgical

colleagues and make a joint decision as to when a computed tomography (CT)

scan or further imaging may be necessary. Individual departments have

large variation in access to CT scans.

Antibiotic availability within the emergency department

and antimicrobial guidelines

All responding EDs reported that antibiotics were

stocked in their departments. The numbers of different antibiotics stocked

in the EDs ranged from 3 to 18, with a median of 8.5. The choice of

antibiotics stocked depended on the individual departments’ antimicrobial

guidelines or regional patterns of pathogen and antibiotic resistance.

Both the penicillin and cephalosporin groups were present in all EDs,

followed in frequency by fluoroquinolones (14 of 16), others (13 of 16),

aminoglycosides (12 of 16), carbapenems (9 of 16), and macrolides (2 of

16).

Support from the intensive care unit and other

departments

Organ failure and septic shock are frequent

indications for ICU admission. However, direct ICU admission of patients

with single organ failure from EDs is determined by individual ICU

admission policy and bed availability. Support from the ICU and in-patient

wards varies across different EDs. During the winter surge and flu

seasons, access to hospital beds is reduced, causing both ED congestion

and compromised sepsis care, especially for those with stable vital signs

or poor premorbid conditions. In some of the surveyed hospitals (4 of 16),

laboratory and pharmacy support for sepsis care after office hours is

limited. This means that those EDs need to dispense drugs or manage

patients without the results of certain laboratory investigations.

Training, audit, and research for sepsis

In terms of training, audits, and research, most of

the surveyed EDs (14 of 16) provided ad hoc training on sepsis management

to physicians and nurses, but none had a specific sepsis outcome audit or

registry. Even though two local studies18

19 provided some insight into

previous sepsis-related mortality, there has been no agreement regarding

standardisation of coding or key performance indicators across different

departments.

Factors affecting the level of care provided

Compared with other time-critical medical

emergencies, the respondents perceived sepsis to be the leading cause of

in-hospital mortality (average: 4.17), followed by acute coronary syndrome

(4.09), stroke (3.00), trauma (2.58), and poisoning (1.08). When the

respondents were asked which time-critical emergencies had the highest

rates of preventable mortality that was not well managed in the ED, trauma

was rated the highest (4.00), followed closely by sepsis (3.42), poisoning

(2.92), stroke (2.42), and acute coronary syndrome (2.25). The top

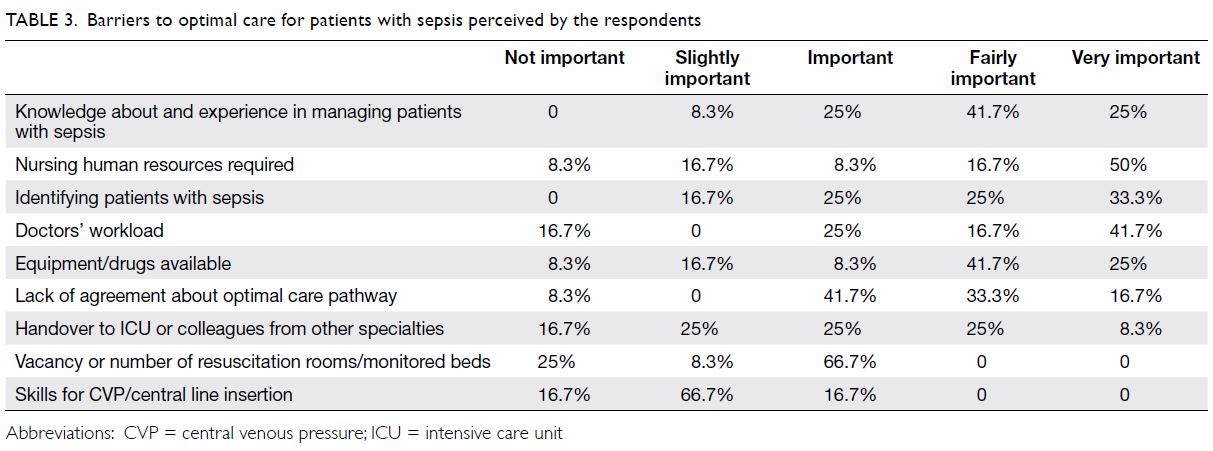

barriers to optimal sepsis care in EDs identified by the respondents were

lack of knowledge and experience and inadequate nursing human resources,

followed by difficulty identifying patients with sepsis. Table

3 lists all of the barriers investigated by the survey and their

perceived importance.

Discussion

In this study, we found varying levels of adoption

of international sepsis guidelines among the responding EDs. Sepsis was

perceived to be the top cause of in-hospital mortality and the second

leading cause of preventable mortality among all time-critical

emergencies. Few EDs had adopted the qSOFA score (which is based on the

Sepsis-3 recommendations) in patient screening at 1 year after its

publication. Early intravenous antibiotic administration within 1 to 2

hours was mandatory according to all of the surveyed EDs’ sepsis

guidelines, and all responding EDs reported that antibiotics were stocked

within their departments.

Emergency departments across the world have an

important responsibility to recognise patients with sepsis, as delays in

treatment and administration of antibiotics have been shown to increase

in-hospital mortality.27 All

responding public EDs had antibiotics available on-site, but few provided

clear guidance on which patients might benefit from timely intravenous

antibiotic administration except those with neutropenic or

post-chemotherapy fever. The widespread availability of intravenous

antibiotics across the EDs is likely a result of the recent Hospital

Authority review on acute management of neutropenic fever. All of the

participating EDs reported the use of either departmental or cluster-wide

guidelines for neutropenic fever, and the latest version of the Hospital

Authority triage guidelines emphasises the importance of its early

recognition and assigns a higher priority to patients with suspected

neutropenic fever.28 Despite

previous studies in Hong Kong that demonstrated high mortality rates among

patients with sepsis without neutropenia,18

19 sepsis generally does not

receive the same level of attention as neutropenia in Hong Kong EDs. To

improve patient outcomes, more emphasis should be placed on early

resuscitation and antibiotic therapy for sepsis in EDs.

Sustained improvement in sepsis care requires not

only guidelines but also more resources and staff training. Further, EDs

in Hong Kong face many challenges such as access blockages and

overcrowding.29 With the rising

level of service demand and competing priorities in EDs, it is important

to understand the barriers to better sepsis care from health care

providers’ perspectives. Our study highlights several challenges. The top

barriers reported included a lack of knowledge and experience, nursing

human resources shortages, and difficulty identifying patients with

sepsis. These findings are similar to those of Carlbom and Rubenfeld,30 who reported a lack of nursing staff, challenges in

the identification of patients with sepsis, and problems with central

venous pressure monitoring as barriers to optimal sepsis care. For

effective changes to take place, it is necessary to overcome these

barriers with more staff training, better nursing human resources

provision in EDs, elevation of staff awareness of sepsis, and provision of

useful bedside tools for sepsis recognition.

The UK Sepsis Six and quality improvement projects

in the UK shed light on how sustained reductions in sepsis mortality can

be achieved in a publicly funded health system similar to that of Hong

Kong.31 In the United States, New

York State has required hospitals to follow a sepsis protocol since 2013.

Results from 2014 to 2016 showed that 82.5% of patients across 149

hospitals had the 3-hour bundle of care (blood cultures, broad-spectrum

antibiotics, and lactate measurement) completed within 3 hours, with a

median time to completion of 1.3 hours.32

Steady improvements in survival of other

time-critical emergencies including ST elevation myocardial infarction,33 acute ischemic stroke,34 and major trauma35

have been achieved in Hong Kong through systemic changes, more staff

training and resources, multidisciplinary collaboration, and regular

interdepartmental audits. Regular and systematic data collection from EDs

in Hong Kong for monitoring, evaluation of performance and processes of

care, and benchmarking is important to assess the impact of various ED

sepsis initiatives.

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. Not all

public EDs in Hong Kong participated in the study. However, we believe

that our findings are representative of the current ED processes of sepsis

care in Hong Kong. We did not include other private EDs, which might

affect the generalisability of our findings; however, ambulances in Hong

Kong bring patients to public EDs only, and 90% of all in-patient care is

provided by public hospitals. We have likely covered the majority of the

EDs in Hong Kong that provide emergency care to patients with sepsis,

especially those in critical condition.

Second, it is possible that some respondents might

have expressed personal bias when responding to the questions, especially

those regarding the barriers to optimal sepsis care. This could have

affected the results despite the fact that respondents were reminded that

their replies should provide the views of the department (not their

personal points of view), and even though the interview guide was shared

in advance to consolidate departmental opinions. Individual questionnaires

targeting various seniority levels of ED staff might be better to address

these questions in the future.

Finally, we relied heavily on the materials

provided by the respondents, and their views do not necessarily reflect

real clinical practice. However, this provides a beginning to facilitate a

better systematic understanding of sepsis care in Hong Kong EDs as a

whole. Future studies are warranted to evaluate actual clinical practice,

patient outcomes in cases of sepsis, and the impact of adopting new sepsis

definitions and international guidelines on a territory-wide basis.

Conclusion

Compared with other time-critical emergencies with

high mortality and impact on patients, sepsis has not received adequate

attention in Hong Kong EDs. The process of care varies considerably among

EDs, and few have departmental sepsis guidelines. With increasing

recognition of the burden of sepsis among Hong Kong EDs, more training and

resources for management of these patients and the establishment of formal

performance indicators should be considered. Systematic routine data

collection for prospective multicentre research is needed to improve

patient care.

Author contributions

Concept and design: KKC Hung, RPK Lam, RSL Lo, CA

Graham.

Acquisition of data: KKC Hung, RPK Lam, MLC Yang, MCK Tai.

Analysis and interpretation of data: KKC Hung, JW Tenney.

Drafting of the article: KKC Hung, RPK Lam.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: KKC Hung, RPK Lam, MLC Yang, MCK Tai.

Analysis and interpretation of data: KKC Hung, JW Tenney.

Drafting of the article: KKC Hung, RPK Lam.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acknowledgement

We thank all of the participants for their time and

support of this study.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of

interest. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility

for its accuracy and integrity.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Survey and

Behavioural Research Ethics Committee of the Chinese University of Hong

Kong (097-16). Verbal informed consent was obtained from the participants.

References

1. Fleischmann C, Scherag A, Adhikari NK,

et al. Assessment of global incidence and mortality of hospital-treated

sepsis. Current estimates and limitations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med

2016;193:259-72. Crossref

2. Kempker JA, Martin GS. The changing

epidemiology and definitions of sepsis. Clin Chest Med 2016;37:165-79. Crossref

3. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et

al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic

Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016;315:801-10. Crossref

4. Churpek MM, Snyder A, Han X, et al.

Quick sepsis-related organ failure assessment, systemic inflammatory

response syndrome, and early warning scores for detecting clinical

deterioration in infected patients outside the intensive care unit. Am J

Respir Crit Care Med 2017;195:906-11. Crossref

5. Lo RS, Brabrand M, Kurland L, Graham CA.

Sepsis—where are the emergency physicians? Eur J Emerg Med 2016;23:159. Crossref

6. Kaukonen KM, Bailey M, Pilcher D, Cooper

DJ, Bellomo R. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria in

defining severe sepsis. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1629-38. Crossref

7. Vincent JL, Martin GS, Levy MM. qSOFA

does not replace SIRS in the definition of sepsis. Crit Care 2016;20:210.

Crossref

8. Macdonald SP, Arendts G, Fatovich DM,

Brown SG. Comparison of PIRO, SOFA, and MEDS scores for predicting

mortality in emergency department patients with severe sepsis and septic

shock. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21:1257-63. Crossref

9. ProCESS Investigators, Yealy DM, Kellum

JA, et al. A randomized trial of protocol-based care for early septic

shock. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1683-93. Crossref

10. Mouncey PR, Osborn TM, Power GS, et

al. Trial of early, goal-directed resuscitation for septic shock. N Engl J

Med 2015;372:1301-11. Crossref

11. ARISE Investigators, ANZICS Clinical

Trials Group, Peake SL, et al. Goal-directed resuscitation for patients

with early septic shock. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1496-506. Crossref

12. Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, et al.

Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic

shock. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1368-77. Crossref

13. Gotts JE, Matthay MA. Sepsis:

pathophysiology and clinical management. BMJ 2016;353:i1585. Crossref

14. Cohen J, Vincent JL, Adhikari NK, et

al. Sepsis: a roadmap for future research. Lancet infect Dis

2015;15:581-614. Crossref

15. Andrews B, Semler MW, Muchemwa L, et

al. Effect of an early resuscitation protocol on in-hospital mortality

among adults with sepsis and hypotension: a randomized clinical trial.

JAMA 2017;318:1233-40. Crossref

16. McIntyre L, Rowe BH, Walsh TS, et al.

Multicountry survey of emergency and critical care medicine physicians’

fluid resuscitation practices for adult patients with early septic shock.

BMJ Open 2016;6:e010041. Crossref

17. Lam SM, Lau AC, Lam RP, Yan WW.

Clinical management of sepsis. Hong Kong Med J 2017;23:296. Crossref

18. Yang ML, Graham CA, Rainer TH. Outcome

after implementation of sepsis guideline in the emergency department of a

university hospital in Hong Kong. Hong Kong J Emerg Med 2015;22:163-71. Crossref

19. Tse CL, Lui CT, Wong CY, Ong KL, Fung

HT, Tang SY. Impact of a sepsis guideline in emergency department on

outcome of patients with severe sepsis. Hong Kong J Emerg Med

2017;24:123-31. Crossref

20. Nutbeam T, Daniels R, Keep J; for the

UK Sepsis Trust. Toolkit: emergency department management of sepsis in

adults and young people over 12 years—2016. Available from:

https://sepsistrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/ED-toolkit-2016-Final-1.pdf.

Accessed 4 May 2018. Crossref

21. Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et

al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of

Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med 2013;39:165-228.

Crossref

22. National Health Service UK. Sepsis

guidance implementation advice for adults. Available from:

https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/sepsis-guidance-implementation-advice-for-adults.pdf.

Accessed

3 Nov 2018.

23. Daniels R, Nutbeam T, McNamara G,

Galvin C. The sepsis six and the severe sepsis resuscitation bundle: a

prospective observational cohort study. Emerg Med J 2011;28:507-12. Crossref

24. Gilbert DN, Moellering RC, Eliopoulos

GM, Chambers HF, Saag MS. The Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy. 42nd

ed. Antimicrobial Therapy Inc; 2012.

25. Ho PL, Wong SS. Reducing bacterial

resistance with IMPACT—Interhospital Multi-disciplinary Programme on

Antimicrobial ChemoTherapy. Hong Kong: Centre for Health Protection; 2012.

26. Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et

al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of

Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med 2017;43:304-77. Crossref

27. Seymour CW, Kahn JM, Martin-Gill C, et

al. Delays from first medical contact to antibiotic administration for

sepsis. Crit Care Med 2017;45:759-65. Crossref

28. A&E Triage Guidelines version 5.

Hong Kong: Hospital Authority; 2016.

29. Chan SS, Cheung NK, Graham CA, Rainer

TH. Strategies and solutions to alleviate access block and overcrowding in

emergency departments. Hong Kong Med J 2015;21:345-52. Crossref

30. Carlbom DJ, Rubenfeld GD. Barriers to

implementing protocol-based sepsis resuscitation in the emergency

department—results of a national survey. Crit Care Med 2007;35:2525-32. Crossref

31. Bentley J, Henderson S, Thakore S,

Donald M, Wang W. Seeking sepsis in the emergency department-identifying

barriers to delivery of the Sepsis 6. BMJ Qual Improv Rep

2016;5:u206760.w3983.

32. Seymour CW, Gesten F, Prescott HC, et

al. Time to treatment and mortality during mandated emergency care for

sepsis. N Engl J Med 2017;376:2235-44. Crossref

33. Cheung GS, Tsui KL, Lau CC, et al.

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST elevation myocardial

infarction: performance with focus on timeliness of treatment. Hong Kong

Med J 2010;16:347-53.

34. Wong EH, Yu SC, Lau AY, et al.

Intra-arterial revascularisation therapy for acute ischaemic stroke:

initial experience in a Hong Kong hospital. Hong Kong Med J

2013;19:135-41.

35. Cheung NK, Yeung JH, Chan JT, Cameron

PA, Graham CA, Rainer TH. Primary trauma diversion: initial experience in

Hong Kong. J Trauma 2006;61:954-60. Crossref