Hong Kong Med J 2020 Oct;26(5):404–12 | Epub 25 Sep 2020

Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Rapid Estimate of Inadequate Health Literacy

(REIHL): development and validation of a

practitioner-friendly health literacy screening

tool for older adults

Angela YM Leung, PhD, FHKAN (Gerontology)1; Esther YT Yu, FHKCFP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)2; James KH Luk, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)3; PH Chau, PhD4; Diane Levin-Zamir, PhD5,6; Isaac SH Leung, MPhil1; KT Cheung, MPhil7; Iris Chi, DSW8

1 Centre for Gerontological Nursing, School of Nursing, The Hong Kong

Polytechnic University, Hong Kong

2 Department of Family Medicine and Primary Care, Li Ka Shing Faculty of

Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

3 Department of Medicine, Fung Yiu King Hospital, Hong Kong

4 School of Nursing, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

5 Department of Health Education and Promotion, Clalit Health Services, Israel

6 School of Public Health, University of Haifa, Israel

7 Centre on Research and Advocacy, Hong Kong Society for Rehabilitation, Hong Kong

8 USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, United States

Corresponding author: Dr Angela YM Leung (angela.ym.leung@polyu.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: This study aimed to develop and

validate a brief practitioner-friendly health literacy

screening tool, called Rapid Estimate of Inadequate

Health Literacy (REIHL), that estimates patients’

health literacy inadequacy in demanding clinical

settings.

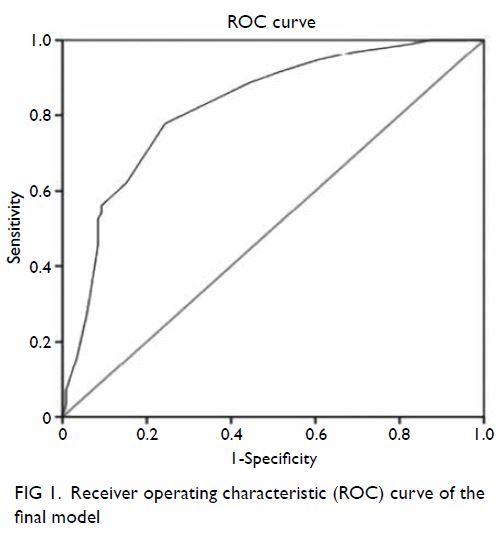

Methods: This is a methodological study of 304

community-dwelling older adults recruited from

one community health centre and five district elderly

community centres. Logistic regression models were

used to identify the coefficients of the REIHL score’s

significant factors. Receiver operating characteristic

(ROC) curve analysis was then used to assess the

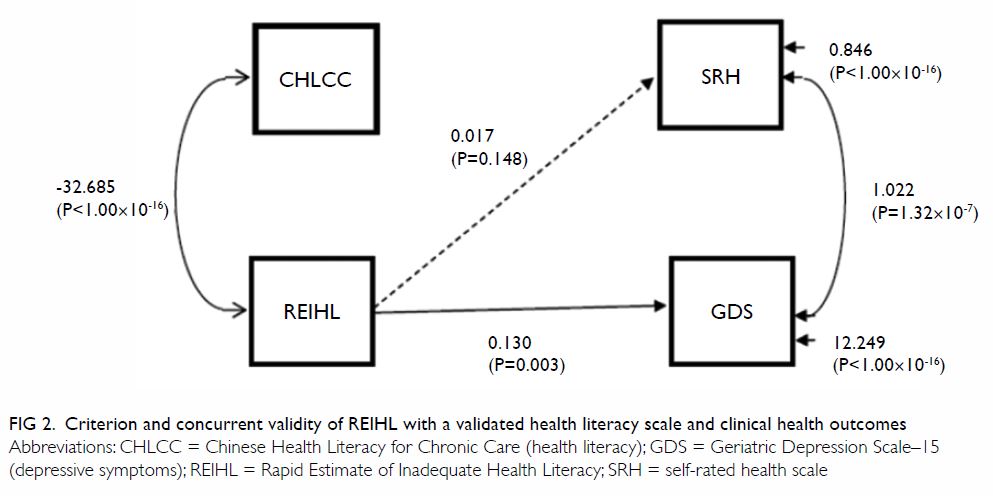

REIHL’s sensitivity and specificity. Path analysis was

employed to examine the REIHL’s criterion validity

with the Chinese Health Literacy Scale for Chronic

Care and concurrent validity with self-rated health

scale and the Geriatric Depression Scale–15.

Results: The REIHL has scores ranging from 0 to

23. It had 76.9% agreement with the Chinese Health

Literacy Scale for Chronic Care. The area under the

ROC curve for predicting health literacy inadequacy

was 0.82 (95% confidence interval=0.78-0.87,

P<0.001). The ROC curve of the REIHL showed that

scores ≥11 had a sensitivity of 77.8% and specificity of

75.6% for predicting health literacy inadequacy. The

path analysis model showed excellent fit (Chi squared

[2, 304] 0.16, P=0.92, comparative fit index 1.00, root

mean square error of approximation <0.001, 90%

confidence interval=0.00-0.04), indicating that the REIHL has good criterion and concurrent validity.

Conclusion: The newly developed REIHL is a

practical tool for estimating older adults’ inadequate

health literacy in clinical care settings.

New knowledge added by this study

-

This paper contributes to the field of health literacy and primary care by:

- providing a practitioner-friendly tool for estimating individuals’ health literacy inadequacy without interrupting clinical workflow; and

- screening high-risk people in China for comprehensive health literacy assessment with the Chinese Health Literacy Scale for Chronic Care.

- Using this rapid estimation may allow doctors/nurses to avoid asking patients to complete a questionnaire, which may interrupt the clinical workflow or take up substantial time during medical consultations.

- The Rapid Estimate of Inadequate Health Literacy could also encourage practitioners to spend more time with those who have inadequate health literacy in health education and counselling.

Introduction

Health literacy is the ability to obtain, read,

understand, and use healthcare information to make

appropriate health decisions and follow treatment

instructions. Inadequate health literacy (IHL) is a

public health concern that is associated with poor

health outcomes and frequent use of health services.1

Identifying groups at risk for IHL is therefore crucial.

Screening tools such as the Rapid Evaluation of Adult

Literacy in Medicine–Revised (REALM-R),2 Rapid

Evaluation of Adult Literacy in Medicine–Short

form,3 Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT-4),4

Newest Vital Sign (NVS),5 and Single-Item Literacy

Screener6 have been developed for assessment of

patients’ health literacy. Nonetheless, each of those

tools has limitations, hindering the extensive use of

rapid health literacy screening in clinical settings.

The REALM-R, Rapid Evaluation of Adult

Literacy in Medicine–Short form, and WRAT-4 focus

only on word recognition,7 representing a narrow

concept of health literacy and failing to address two

other crucial dimensions: ‘interpretation of health

information’ and ‘health decision making’.7 8 The

REALM-R and WRAT-4 health literacy assessments

require 2 to 3 and 3 to 5 minutes, respectively, to

administer. Thus, using the REALM-R or WRAT-4

demands special arrangements in clinical settings:

patients may be required to complete them prior

to consultation, and they may interrupt the usual

clinical workflow. An alternative is for the doctor to conduct the assessment, but the typical out-patient

clinical consultation period is about 7 minutes for

each patient, and adequate health literacy assessment

would occupy multiple minutes of this period.

The NVS is another recommended tool for

quick health literacy screening that compensates for

the shortcomings of previous tools by addressing the

need to understand and interpret health information

from a designated nutritional label. After reading the

label, the client answers six questions about it. The

assessment of these capacities by the NVS is both a

strength and a shortcoming, as it requires more time

to complete.9 Notably, older adults take 11.7 minutes

(range, 6-28 minutes) to complete the NVS, so its

practicality for quick assessment of elderly patients’

health literacy is limited.10

Another rapid health literacy assessment

tool is the Short-Form Test of Functional Health

Literacy in Adults, a 36-item tool that assesses

clients’ comprehension and numeracy abilities.11 It

is recommended to allot 7 minutes to complete the

assessment, and clients should stop when that time

is up. However, time-limited assessments can be

challenging for older adults because of their delayed

cognitive processing or age-related slowness. These

effects are typical but not pathological with age,

rendering the Short-Form Test of Functional Health

Literacy in Adults inappropriate for this population.12

Further, most of its contents were based on the US

healthcare system, making its generalisability to

other countries questionable.

The Single-Item Health Literacy Screening is

the simplest health literacy assessment, containing

only one item. Its key limitation is possible self-report

bias, as it assesses clients’ perceived ability to

read and understand health information from written

material, which may not reflect their actual abilities.6

Given the shortcomings of existing rapid

health literacy screening tools and the need to assess

patients’ health literacy in clinical settings, there

is a need to develop a rapid tool for non-English-speaking

older adults that can be used in different

healthcare systems and is based on available patient

data. The project team has developed several health

literacy tools for Chinese populations, including the

Chinese Health Literacy Scale for Diabetes,13 Chinese

Health Literacy Scale for Chronic Care (CHLCC),14

and Chinese Health Literacy Scale for Diabetes–Multiple Choice version.15 Although these tools

can be used in Chinese-speaking populations, they

require several minutes for clients to complete,

which may not be ideal for rapid screening in

busy clinics. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to

develop and validate a brief practitioner-friendly

health literacy screening tool, the Rapid Estimate of

Inadequate Health Literacy (REIHL), which employs

a multivariable prediction model to determine

patients’ risk for IHL in a demanding clinical setting.

Methods

Study design and participants

This is a cross-sectional, methodological study

that was conducted from August 2010 to January

2011. The Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable

Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or

Diagnosis guidelines were also followed.16

Older adults from one community health

centre and five district elderly community centres

in Hong Kong were recruited. The inclusion criteria

were: (1) age ≥50 years; (2) cognitively capable (Short

Portable Mental Status Questionnaire Chinese

version score ≥7); and (3) able to communicate in

Cantonese. The sample size calculation was derived

from a receiver operating characteristic (ROC)

power calculation using the ‘power.roc.test’ function

under the ‘pRCO’ library in R version 3.6. Assuming

that the newly developed tool’s area under the curve

0.60, type 1 error 0.05, power 0.8, and attrition 20%,

at least 298 subjects should be recruited.17

Recruitment strategies included posters

at community centres, monthly meetings, and

in-person contact. All participants were interviewed

to assess their eligibility to participate. Ethical

approval was obtained from the Institutional Review

Board of The University of Hong Kong/Hospital

Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (Ref UW 09-033).

Procedure for developing the Rapid Estimate

of Inadequate Health Literacy

The newly developed REIHL screening tool was

devised using model estimation. Unlike other scale

development, we did not create the items for the

REIHL but collected socio-demographic data (age,

gender, education level, types of chronic illness) and

conducted the CHLCC on the subjects. Scores on

the CHLCC were used to determine which subjects

had IHL. People with CHLCC scores of <36 were

considered as having IHL. We then created a dummy

variable representing IHL (1: IHL; 0: adequate

health literacy). Socio-demographic factors (eg,

age, education level, types and number of chronic

illnesses) associated with IHL were identified, and

these became the items of the REIHL. Chronic

illnesses refer to conditions that last 1 year or more

and lead to limitations in activities of daily living

and/or require ongoing medical attention.18

Measurement

People with IHL were more likely to have more

depressive symptoms19 20 and poor self-rated health

(SRH).21 22 We therefore checked the criterion

validity and concurrent validity of REIHL with the

following validated scales.

The CHLCC was used to check the criterion

validity of REIHL. The CHLCC is a 24-item tool for measuring health literacy in Chinese populations

with four subscales (remembering, understanding,

applying, and analysing). It has good internal

(Cronbach’s alpha, 0.91) and test-retest (intraclass

correlation coefficient, 0.77; P<0.01) reliability.14

The Geriatric Depression Scale–15 (GDS-15)

and the SRH scale were used to check the REIHL’s

concurrent validity. The GDS-15 is used to assess

older adults’ depressive symptoms,23 and it has been

translated into Chinese and validated in Hong Kong

with good psychometric properties (Cronbach’s

alpha, 0.82; item-total correlation, 0.23-0.66).24 25 Its

total score ranges from 0 to 15, with higher values

representing increased depression levels. The SRH

is a validated single-item scale for assessing general

health status.26 It is a subjective assessment of general

health, asking ‘In the last 3 months, how would you

describe your health status?’ Five options are given:

‘very good’, ‘good’, ‘fair’, ‘poor’, or ‘very poor’, coded as

integers from 1 (very good) to 5 (very poor).

Statistical analyses

There were a few items of missing data, which

comprised about 2% of all data. Missing values

were filled in using multiple imputation in SPSS

(Windows version 25.0; IBM Corp, Armonk

[NY], US). Chi squared tests were used to assess

the bivariate relationships between demographic

variables and IHL. Logistic regression analyses were

used to further assess the multivariate relationships

among the factors that were significantly associated

with IHL. Model adequacy was evaluated

by Nagelkerke’s R2.27 To obtain an optimistic

assessment of the model’s prediction performance

and avoid overfitting, 10-fold cross-validation was

used, and error mean square (EMS) was reported.

To select the best model, we chose the model with

the smallest EMS and lowest Bayesian information

criterion (BIC) values. We derived the point scores

for REIHL with reference to the Framingham Study

Risk Score.16 The score for each item of the REIHL is

calculated by dividing its coefficient by the smallest

coefficient and then rounding up to the next highest

integer. The total REIHL score is the sum of the

scores of all items in the REIHL.

To test the reliability of the REIHL, we used

ROC curve analysis28 to assess its sensitivity and

specificity. We choose the optimum sensitivity

and specificity based on maximisation of Youden’s

index.29 We assessed the corresponding sensitivity

and specificity of each potential cut-off point. The

chosen cut-off point was the one with the largest

Youden’s index (ie, sensitivity + specificity − 1). We

also assessed the criterion validity and concurrent

validity of REIHL. Criterion validity refers to the

stated criterion, that is, the correspondence between

the results of this newly developed scale and those

of a validated health literacy scale. Concurrent validity is the extent to which a test relates to

another previously validated metric. Here, we tested

the REIHL’s criterion validity with the CHLCC and

the REIHL’s concurrent validity with two health

outcomes (depression and SRH). Path analysis30 was

also used to examine the criterion and concurrent

validity of REIHL with a validated health literacy

scale (CHLCC) and two health outcomes (depressive

symptoms and SRH) using MPlus version 7.31 We

assessed three fit indices to determine the goodness

of fit of the model: a model with non-significant Chi

squared value (P>0.05), comparative fit index ≥0.95,

and root mean square error of approximation ≤0.10

was considered to be a well-fitting model.32 33 We

also inspected the direction and significance of the

standardised estimate coefficients to determine the

effects of one variable on another.

Results

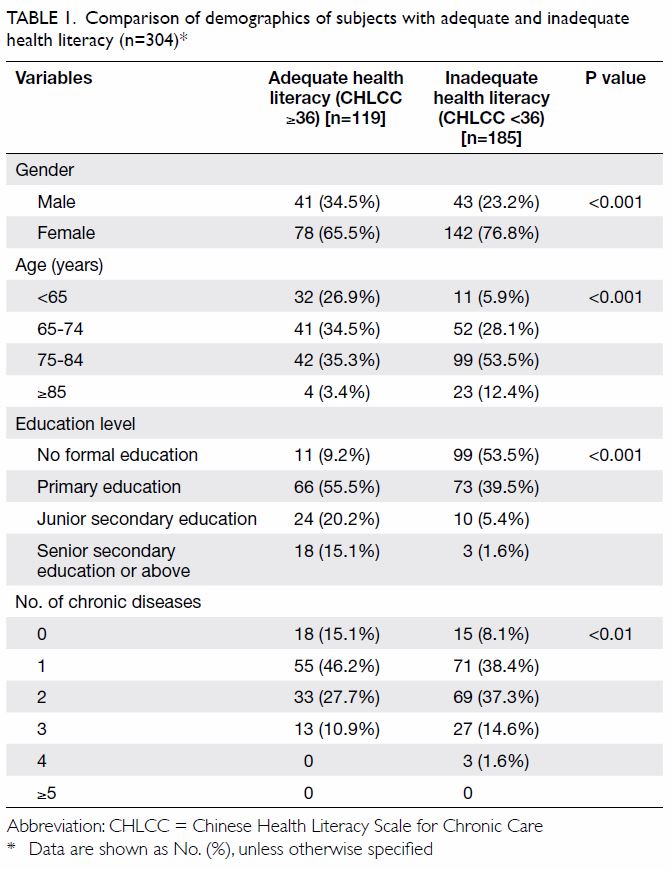

A total of 304 subjects were included in the analysis,

of whom 220 (72.4%) were female. In all, 185 (60.9%)

subjects were shown to have IHL when assessed by

the health literacy scale (CHLCC score <36). Age, gender, education level, and number of chronic

illnesses were significantly associated with CHLCC

(Table 1).

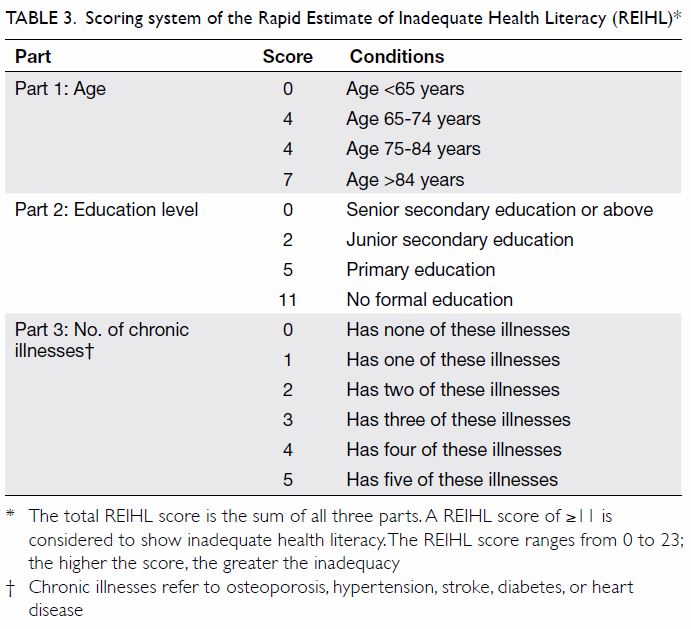

Table 1. Comparison of demographics of subjects with adequate and inadequate health literacy (n=304)

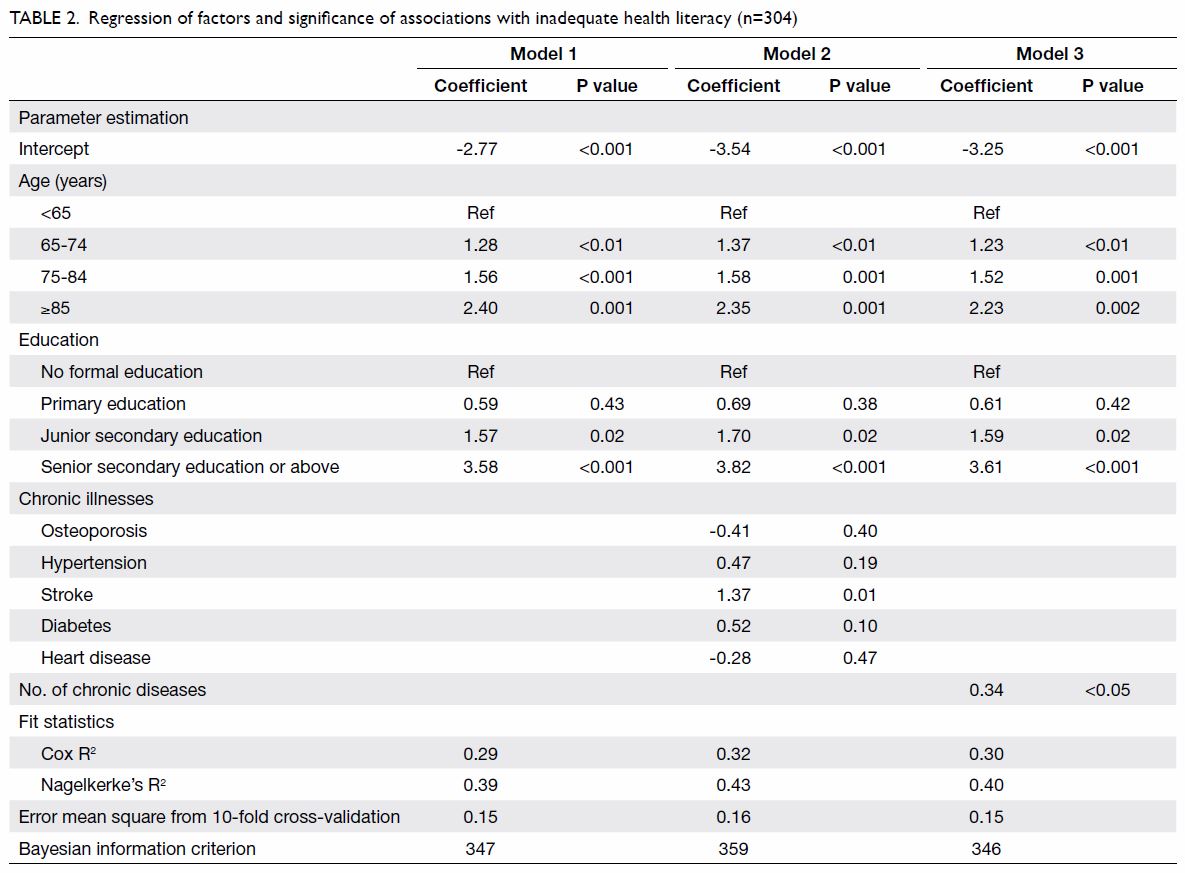

Because gender was significantly correlated

with education, we selected education level as the

representative variable used in the regression models

(Table 2). Model 1 employed a regression model that

incorporated age and education, and the results

were: Nagelkerke’s R2 0.39, EMS 0.15, and BIC 347.

To form Model 2, we added five chronic illnesses (ie,

diabetes, hypertension, stroke, heart disease, and

osteoporosis) into the regression; Nagelkerke’s R2

increased to 0.43, EMS to 0.16, and BIC to 359. In

Model 3, the selected chronic illnesses were replaced

by the number of chronic illnesses, and Nagelkerke’s

R2 became 0.40, EMS 0.15, and BIC 346. Because

Model 3 had the lowest BIC and EMS values, and its

Nagelkerke’s R2 was comparable to those of the other

two models, we considered Model 3 as the best and

final model.

Table 2. Regression of factors and significance of associations with inadequate health literacy (n=304)

The coefficients of age, education level, and

number of chronic illnesses were identified in Model

3. The smallest coefficient was 0.34, and that value

was used as the denominator to calculate the score

for each item. Age was categorised and scored as

0, 4, 4, or 7; education level was scored as 0, 2, 5,

or 11; and chronic illnesses were scored from 0 to

5 depending on their number (Table 3). Therefore,

the total REIHL score ranged from 0 to 23. The

REIHL had 76.9% agreement with the CHLCC, the

validated, reliable health literacy scale. The area

under the ROC curve for predicting IHL was 0.82

(95% confidence interval=0.78-0.87, P<0.001; Fig 1).

The curve for the REIHL showed that scoring ≥11

had a sensitivity of 77.8% and specificity of 75.6% for

predicting IHL. This criterion identified 60.9% of the

participants as having IHL.

All of the REIHL items had unique scores

except for two items under ‘Age’ that had the same

score (ie, 4) after rounding up. The actual score for

those aged 65 to 74 years was 3.71 (=1.27/0.34),

whereas that for those aged 75 to 84 years was

4.44 (=1.55/0.34). Because the difference between

the actual scores (3.71 and 4.44) was almost 1, we

considered the possibility of adjusting the score of

the item ‘aged 75 to 84 years’ to 5. The sensitivity

and specificity of the REIHL were 72.4% and 79.8%,

respectively, when adjusted accordingly. These

results were not significantly different from those

before adjustment. The agreement between REIHL

and CHLCC in the adjusted model was 75.3%, which

was lower than that before adjustment. The area

under the ROC curve of the adjusted REIHL was

0.83 (ie, very close to the corresponding value of

the unadjusted version). In view of the insignificant

improvement in psychometric properties, we

propose to not adjust the scoring of the item ‘aged

75 to 84 years’, leaving it as 4.

The path analysis model showed excellent fit

(Chi squared [2, 304] 0.16, P=0.92, comparative fit

index 1.00, root mean square error of approximation

<0.001, 90% confidence interval=0.00-0.04),

indicating the criterion validity and concurrent

validity of the REIHL (Fig 2). The path between

the REIHL and CHLCC (β= −32.69, P<0.001) was

statistically significant, implying that the REIHL was

significantly negatively associated with the CHLCC.

This shows the criterion validity of REIHL with a

validated health literacy instrument. A negative

association between the two scales is reasonable and

expected because the REIHL measures inadequacy,

unlike the CHLCC, which measures adequacy. The

path between the REIHL and the GDS-15 (β = 0.13,

P<0.01) was also statistically significant, but the path

between the REIHL and SRH was not. This implies

that there was a significant relationship between IHL

and depressive symptoms. The path between the

GDS-15 and SRH (β=1.02, P<0.001) was statistically

significant, indicating a strong relationship between

depression and poor SRH.

Figure 2. Criterion and concurrent validity of REIHL with a validated health literacy scale and clinical health outcomes

Discussion

The newly developed REIHL is a reliable screening

tool for estimating IHL among older adults in clinical

settings. Although REIHL is an estimation tool, it had

very good agreement with a validated health literacy

measure (CHLCC). This implies that if clinicians

have limited time to assess patients’ health literacy,

they could estimate it using the REIHL rather than

actually measuring patients’ health literacy levels.

The strengths of the REIHL are its reliability

and simplicity. We used several methods to test the

tool’s reliability. For instance, ROC analysis found

that the area under the curve was more than 80%,

and the sensitivity and specificity of the REIHL with a cut-off point of 11 reached an acceptable

level, indicative of an accurate assessment tool.

The relationships between REIHL and CHLCC

were well illustrated in the path analysis, indicating

that REIHL has reasonably good criterion validity.

Previous literature showed that adults with IHL were

more likely to have depressive symptoms19 20 and

poor SRH.21 22 The path analysis showed that REIHL

was significantly associated with GDS-15 but not

with SRH; however, the GDS-15 was significantly

associated with SRH, and the model showed good

fit. These findings confirmed the concurrent validity

of REIHL, as estimated IHL was significantly

associated with depression. This result provides

some added value, as IHL was indirectly associated

with poor SRH via depression. This means that older

adults’ poor SRH was caused not directly by IHL, but

by the presence of depression.

Three of the REIHL’s items (age, education,

and number of chronic illnesses) may be risk factors

for depression, so testing the tool’s association with

depression might be a challenge analogous to testing

the relationship between risk factors and poor

health outcomes. However, we are confident that

the inclusion of these items in the REIHL is a good

design choice to highlight the heterogeneity of older

adults and remind practitioners to be sensitive to the

differentiation among clients. People of advanced

age and low education are more likely to have

poor health outcomes (including depression), but

the age and education level at which practitioners

should be mindful of IHL remains unclear. The

REIHL is a reminder to practitioners to pay proper

attention to these important aspects so that they

can communicate with patients to self-manage

their health issues. Advocating the use of REIHL

is not intended to replace the concept of universal precaution in health literacy and its adoption, but it

highlights a population that needs special attention

regarding health literacy. In clinics where most

clients are older adults, practitioners could thereby

direct their limited time and resources to those in

the greatest need. By contrast, when encountering

less-educated clients, some practitioners do not

attempt to educate them, assuming they are unable

to understand or apply the information. In such

situations, the REIHL may encourage practitioners

to adopt strategies such as referring clients with IHL

to training. In one US study, people with IHL were

referred to regular telephone counselling provided

by health coaches (trained nurses, health educators,

and diabetes educators) for 12 months.34 The health

coaches delivered health advice/messages in simple

sentences over the phone. In a Hong Kong study,

multi-component nurse-led group meetings derived

from the concept of photovoice were arranged for

patients with diabetes, hypertension, and limited

health literacy.35 In these meetings, participants

used photos to express barriers to and facilitators

of physical activity and developed plans to improve

their health status.35 These two examples illustrate

how people with IHL have been supported to

communicate with healthcare professionals to make

their health decisions.

The REIHL can be used easily by clinicians

provided that they know the clients’ age, education

level, and number of chronic illnesses. Its scoring

system is simple, with the sum of all items forming

the total score. The different levels within each item

have unique scores, except for two age categories

(65-74 and 75-84 years), to both of which the score

4 was assigned. We investigated the possibility of

adding one more point to the latter category’s score,

but this did not contribute additional sensitivity or

specificity; therefore, we decided to keep the status

quo.

The REIHL could contribute to the hands-on

1-minute estimation of patients’ health literacy

levels that is sometimes performed in clinical areas.

Such a swift assessment allows practitioners to make

decisions in health education, such as avoiding the

use of jargon, providing simplified information and

illustrations, using the ‘teach-back’ method, and

encouraging patients’ questions. These strategies can

improve health behaviours among those with IHL.36

As IHL is a common phenomenon in clinical settings,

the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and

the Institute for Healthcare Improvement of the US

recommend that practitioners use the teach-back

method as a strategy of taking universal precautions

for health literacy (ie, applying such precautions to

all patients).37 In the teach-back method, patients

are asked to repeat the instructions they receive

from doctors and nurses, allowing healthcare

professionals to check patients’ understanding of the health messages and then re-teach or modify

the method of presentation if the patients do not

demonstrate comprehension. Throughout the

process, it is recommended that doctors and nurses

have a caring attitude and use plain language in

communication.38

Unlike other rapid estimation tools for health

literacy, such as the REALM-R, the REIHL does

not require clients to read aloud. This enables

practitioners to estimate patients’ health literacy

without embarrassing them, which is particularly

suitable to Chinese culture in view of the concept of

‘saving face’. Its application is highly recommended in

the management of geriatric patients, as such patients

are a heterogeneous group in terms of health literacy

adequacy. Older patients’ literacy problems may not

be obvious, as some may conceal their problems

out of shame or may not recognise their difficulties

with reading. Such individuals may be unable to ask

relevant health questions or may misunderstand

healthcare providers’ recommendations. As older

patients tend to have many co-morbidities, they

need to navigate the health care system and interpret

complex information, which are challenging for

people with IHL. Understanding patients’ health

literacy could allow the implementation of strategies

that could potentially improve their health and

reduce emergency attendance and hospital

admissions. Two strategies have been proven effective

to facilitate medication adherence and health

literacy. A self-management education programme

(two 30- to 40-minute weekly meetings followed

by four phone-based educational sessions) tailored

to health literacy was shown to increase adherence

to antihypertensive medication.39 Another strategy

is the use of a tailor-made comic book to facilitate

medication counselling sessions (two 45-minute

face-to-face meetings) administered by trained

volunteers.40 41 Because people with IHL are more

likely to have low confidence in medicine taking,33 42

health education of this kind can be beneficial to

people with chronic illnesses.

The REIHL is a screening tool for health literacy.

Because of its estimated nature and capacity for rapid

implementation, it is best used in ambulatory care or

out-patient care clinics. The REIHL cannot replace

the CHLCC, which assesses health literacy levels

accurately and directly. However, the REIHL is good

at identifying members of the high-risk population

on whom the administration of the CHLCC or other

health literacy tests is warranted. The prevalence of

IHL in this sample was high (61%), and this result is

comparable to those found in other populations: in

the Netherlands, the prevalence of IHL in patients

with arterial vascular disease was 76.7%,43 whereas

in Brazil, more than half of people with hypertension

(54.6%) had IHL.44 As the prevalence of IHL is

high across various populations, there should be no problems with the generalisation of this health

literacy tool. However, to determine whether the

REIHL can be applied in other populations or

nations, a cross-national study should be carried out

in future.45

Several limitations of this study should be

acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design did

not allow us to investigate the causal relationship

between health literacy and health outcomes.

Second, because only Chinese subjects were

included, the threshold is only valid for Chinese older

adults, and whether the results can be generalised to

other non-Chinese populations is not known. Future

studies should investigate the scale’s psychometric

properties in other populations. Third, we recruited

volunteers from community district elderly centres,

so there is some selection bias based on interest and

motivation. Further, the tool measures the risk for

IHL based on patients’ background information;

thus, it is not sensitive to changes in an individual’s

personal health literacy level. Previous studies have

shown that cognitive impairment is strongly related

to low health literacy. However, we restricted the

inclusion criteria to those without impaired cognitive

function.46 Fourth, the REIHL relies on self-reported

items, so under-reporting or over-reporting are

possible. Inaccurate reporting may be the result of

stigma or the potential for embarrassment associated

with low education levels or literacy abilities. Caution

should be applied when interpreting REIHL scores.

Finally, the present dataset is too small to be split

into training and validation datasets. Future studies

with larger datasets should be used to validate this

scale.

Conclusion

The REIHL is a practitioner-friendly tool for

screening older adults’ risk for IHL, which can be

applied in clinical settings to identify at-risk groups.

This tool is particularly useful in demanding clinical

areas where older adults constitute the majority of

patients. Future studies should assess how using the

REIHL in a community clinical setting encourages

healthcare providers to relate better to patients with

lower health literacy and improves communication

with them.

Author contributions

Concept or design of study: AYM Leung, PH Chau, I Chi.

Acquisition of data: ISH Leung, KT Cheung.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: ISH Leung, KT Cheung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: AYM Leung, EYT Yu, JKH Luk, D Levin-Zamir, I Chi.

Acquisition of data: ISH Leung, KT Cheung.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: ISH Leung, KT Cheung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: AYM Leung, EYT Yu, JKH Luk, D Levin-Zamir, I Chi.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, JKH Luk was not involved in the

peer review process of the article. Other authors have

disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the invaluable

contribution of the study participants. Special thanks go to

the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful review and

guidance.

Declaration

The findings of this study were presented in part as a poster

at the 10th International Symposium on Healthy Aging, Hong

Kong. Leung ISH, Leung AYM, Chau PH (2015, March 7-8).

Rapid Estimate of Inadequate Health Literacy (REIHL) for

community-dwelling Chinese older adults.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available

on request from the corresponding author. The data are not

publicly available because of privacy or ethical restrictions.

Funding/support

This project was funded by Seed Funding for Basic Research, HKU 2010-11 (Project No: 200911159075) of the University of Hong Kong.

Ethics approval

Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of The University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong

West Cluster (Ref UW 09-033).

References

1. Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpem DJ,

Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an

updated systematic review. Ann Int Med 2011;155:97-107. Crossref

2. Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, et al. Rapid estimate

of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening

instrument. Fam Med 1993;25:391-5.

3. Arozullah AM, Yarnold PR, Bennett CL, et al. Development

and validation of a short-form, rapid estimate of adult

literacy in medicine. Med Care 2007;45:1026-33. Crossref

4. Wilkinson GS, Robertson GJ. Wide Range Achievement

Test–Fourth Edition (WRAT-4). Lutz, FL: Psychological

Assessment Resources; 2006. Crossref

5. Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, et al. Quick assessment of

literacy in primary care: the newest vital sign. Ann Fam

Med 2005;3:514-22. Crossref

6. Morris NS, MacLean CD, Chew LD, Littenberg B. The

Single Item Literacy Screener: evaluation of a brief

instrument to identify limited reading ability. BMC Fam

Pract 2006;7:21. Crossref

7. Haun JN, Valerio MA, McCormack LA, Sørensen K,

Passche-Orlow MK. Health literacy measurement: an

inventory and descriptive summary of 51 instruments. J

Health Comm 2014;19 Suppl 2:302-33. Crossref

8. Carpenter CR, Kaphingst KA, Goodman MS, Lin MJ,

Melson AT, Griffey RT. Feasibility and diagnostic

accuracy of brief health literacy and numeracy screening

instruments in an urban emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2014;2:137-46. Crossref

9. Shah LC, West P, Bremmeyr K, Savoy-Moore RT. Health

literacy instrument in family medicine: the “newest vital

sign” ease of use and correlates. J Am Board Fam Med

2010;23:195-203. Crossref

10. Patel PJ, Joel S, Rovena G, et al. Testing the utility of the

newest vital sign (NVS) health literacy assessment tool

in older African-American patients. Patient Educ Couns

2011;85:505-7. Crossref

11. Baker DW, Williams MV, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA,

Nurss J. Development of a brief test to measure functional

health literacy. Patient Educ Couns 1999;38:33-42. Crossref

12. Robinson S, Moser D, Pelter MM, Besbitt T, Paul SM,

Dracup K. Assessing health literacy in heart failure

patients. J Card Fail 2011;17:887-92. Crossref

13. Leung AY, Lou VW, Cheung MK, Chan SS, Chi I.

Development and validation of Chinese health literacy

scale for diabetes. J Clin Nurs 2013;22:2090-9. Crossref

14. Leung AY, Cheung MK, Lou VW, et al. Development and

validation of the Chinese Health Literacy Scale for chronic

care. J Health Comm 2013;18 Suppl 1:205-22. Crossref

15. Leung AY, Lau HF, Chau PH, Chan EW. Chinese Health

Literacy Scale for Diabetes–multiple-choice version

(CHLSD-MC): a validation study. J Clin Nurs 2015;24:2679-82. Crossref

16. Sullivan LM, Massaro JM, D’Agostino RB Sr. Presentation

of multivariate data for clinical use: The Framingham Study

risk score functions. Stat Med 2004;23:1631-60. Crossref

17. Li F, He H. Assessing the accuracy of diagnostic tests.

Shanghai Arch Psychiatry 2018;30:207-12.

18. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, US

Government. About chronic diseases. Available from:

https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/index.htm. Accessed 17 May 2020.

19. Rhee TG, Lee HY, Kim NK, Han G, Lee J, Kim K. Is health

literacy associated with depressive symptoms among

Korean adults? Implications for mental health nursing.

Perspect Psychiatr Care 2017;53:234-42. Crossref

20. Puente-Maestu L, Calle M, Rodríguez-Hermonsa JL, et al.

Health literacy and health outcomes in chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease. Respir Med 2016;115:78-82. Crossref

21. Protheroe J, Whittle R, Bartlam B, Estacio EV, Clark L,

Kurth J. Health literacy, associated lifestyle and

demographic factors in adult population of an English city:

a cross-sectional survey. Health Expect 2017;20:112-9. Crossref

22. Liu YB, Liu L, Li YF, Chen YL. Relationship between health

literacy, health-related behaviors and health status: a

survey of elderly Chinese. Int J Environ Res Public Health

2015;12:9714-25. Crossref

23. Sheik JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS):

recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin

Gerontol 1986;5:165-73. Crossref

24. Lee HC, Chiu HF, Kwok WY, et al. Chinese elderly and

the GDS short form: a preliminary study. Clin Gerontol

1993;14:37-42.

25. Boey KW, Chiu HF. Assessing psychological well-being of

the old-old: a comparative study of GDS-15 and GHQ-12.

Clin Gerontol 1998;19:65-75. Crossref

26. Lundberg O, Manderbacka K. Assessing reliability of a

measure of self-rated health. Scand J Soc Med 1996;24:218-24. Crossref

27. Nagelkerke NJ. A note on a general definition of the

coefficient of determination. Biometrika 1991;78:691-2. Crossref

28. Zweig MH, Campbell G. Receiver-operating characteristic

(ROC) plots: a fundamental evaluation tool in clinical

medicine. Clin Chem 1993;39:561-77. Crossref

29. Ruopp MD, Perkins NJ, Whitcomb BW, Schisterman EF.

Youden Index and optimal cut-point estimated from

observations affected by a lower limit of detection. Biom

J 2008;50:419-30. Crossref

30. Garson GD. Path analysis. Asheboro (NC): Statistical

Associates Publishers; 2014.

31. Muthén LK, Muthén BO. MPlus (version 6) [computer

software]. Los Angeles (CA): Muthén & Muthén; 2010.

32. Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models.

Psychol Bull 1990;107:238-46. Crossref

33. Raykov T, Marcoulides GA. A First Course in Structural

Equation Modeling. 2nd ed. Mahwah (NJ): Erlbaum; 2006.

34. Hadden KB, Arnold CL, Curtis LM, et al. Barriers and

solutions to implementing a pragmatic diabetes education

trial in rural primary care clinics. Contemp Clin Trials

Commun 2020;18:100550. Crossref

35. Leung AY, Chau PH, Leung IS, et al. Motivating diabetic

and hypertensive patients to engage in regular physical

activity: a multi-component intervention derived from

the concept of photovoice. Int J Environ Res Public Health

2019;16:1219. Crossref

36. Nouri SS, Rudd RE. Health literacy in the “oral exchange”:

an important element of patient-provider communication.

Patient Educ Couns 2015;98:565-71. Crossref

37. Yen PH, Leasure AR. Use and effectiveness of the teach-back

method in patient education and health outcomes.

Fed Pract 2019;36:284-9.

38. Warde F, Papadakos J, Papadakos T, Rodin D, Salhia M,

Giuliani M. Plain language communication as a priority

competency for medical professionals in a globalized

world. Can Med Educ J 2018;9:e52-9. Crossref

39. Delavar F, Pashaeypoor S, Negarandeh R. The effects of

self-management education tailored to health literacy on

medication adherence and blood pressure control among

elderly people with primary hypertension: a randomized

controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2020;103:336-42. Crossref

40. Leung AY, Leung IS, Liu JW, Ting S, Lo S. Improving

health literacy and medication compliance through comic

books: a quasi-experimental study in Chinese community-dwelling

older adults. Glob Health Promot 2018;25:67-78.Crossref

41. Wu SW, Tse DT, Chui JC, et al. Educational comic book

versus pamphlet for improvement of health literacy in

older patients with type II diabetes mellitus: a randomized

controlled trial. Asian J Gerontol Geriatr 2017;12:60-4.

42. Lee YM, Yu HY, You MA, Son YJ. Impact of health literacy

on medication adherence in older people with chronic

diseases. Collegian 2017;24:11-8. Crossref

43. Strijbos RM, Hinnen JW, van den Haak RF, Verhoeven BA,

Koning OH. Inadequate health literacy in patients with

arterial vascular disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg

2018;56:239-45. Crossref

44. Costa VR, Costa PD, Nakano EY, Apolinário D, Santana AN.

Functional health literacy in hypertensive elders at primary

health care. Rev Bras Enferm 2019;72 Suppl 2:266-73. Crossref

45. Sharma S, Weathers D. Assessing generalizability of

scales used in cross-national research. Int J Res Mark

2003;20:287-95. Crossref

46. Federman AD, Sano M, Wolf MS, Siu AL, Halm EA. Health

literacy and cognitive performance among older adults. J

Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:1475-80. Crossref

sref