Hong Kong Med J 2020 Oct;26(5):397–403 | Epub 16 Oct 2020

Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Treatment of patients with Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome in a tertiary hospital

Karen Ng, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology), FHKCOG; Patricia NP Ip, MB, ChB; KW Yiu, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology), FHKCOG; Jacqueline PW Chung, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology), FHKCOG; Symphorosa SC Chan, MD, FHKCOG

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Karen Ng (ngkaren@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome is an uncommon congenital

malformation characterised by agenesis or

hypoplasia of the vagina and uterus. Here, we

describe the treatment of patients with MRKH

syndrome in a tertiary hospital.

Methods: This retrospective study included patients

with MRKH syndrome attending the Paediatric and

Adolescent Gynaecology Clinic in a tertiary hospital.

Their clinical manifestations, examinations, and

methods for neovagina creation were recorded.

Among patients who underwent vaginal dilation

(VD), therapy duration, vaginal width and length

at baseline and after VD, complications, and sexual

activity and dyspareunia outcomes were evaluated.

Results: Forty nine patients with MRKH syndrome

were identified. Their mean age at presentation was

17.9 years; 69.4% and 24.5% of patients presented for

primary amenorrhoea treatment and vaginoplasty,

respectively. Forty eight patients had normal renal

imaging findings and 46 XX karyotypes. Seventeen

(34.7%) patients underwent VD as first-line therapy;

three did not complete the therapy. Two had surgical

vaginoplasty, whereas five achieved adequate vaginal length by sexual intercourse alone; 25 had not yet

requested VD. The mean duration of VD was 16±10.2

(range, 4-35) weeks. The widths and lengths of the

vagina at baseline and after VD were 1.1±0.28 cm

and 1.3±0.7 cm, and 3.1±0.5 cm and 6.9±0.9 cm,

respectively. The overall success rate of VD was

92.3%. Vaginal spotting was the most common

complication (21%); only one patient reported

dyspareunia.

Conclusions: Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome is an uncommon

condition that requires multidisciplinary specialist

care. Vaginal dilation is an effective first-line approach for

neovagina creation.

New knowledge added by this study

- Most patients were diagnosed with Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome after they presented with primary amenorrhoea. Most patients with MRKH syndrome exhibited normal renal imaging findings, but did not possess a uterus.

- Among patients with MRKH syndrome who completed vaginal dilation (VD) therapy, the success rate was 92.3%, based on reports of subjective sexual satisfaction.

- The most common complication during VD therapy was vaginal spotting (21% of patients), which resolved with conservative management or the use of vaginal oestrogen cream.

- For patients with MRKH syndrome who discontinued treatment prior to completion of VD therapy, a considerably shorter second course of treatment was sufficient to achieve satisfactory vaginal length.

- Resources should be allocated for provision of psychological services, including the option for group-based therapy, because these may be helpful for patients with MRKH syndrome and their caregivers.

- VD therapy should be recommended as first-line treatment for the creation of a neovagina in patients with MRKH syndrome, following careful consideration of local expertise, patient preferences, and patient ability to maintain compliance for the duration of therapy.

Introduction

Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH)

syndrome is a congenital malformation characterised

by failed development of the Müllerian duct, which

leads to vaginal agenesis, often accompanied by

uterine agenesis. It is estimated to occur in one in

4000 to 5000 births.1 Most patients present with primary amenorrhoea, but exhibit normal secondary

sexual characteristics. Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome is reportedly associated with other

malformations including renal, skeletal, and auditory

manifestations.2 3 The creation of a functional

neovagina is a component of treatment performed

to aid women in achieving a normal sexual life. The timing for the creation of a neovagina depends on

the patient. However, treatment should be deferred

beyond late adolescence to allow each patient to

provided informed consent and participate in the

treatment process.4 Both surgical and non-surgical

methods have been described for the creation of

a neovagina. Regarding surgical options, various

grafts or moulds may be used; other techniques

include traction vaginoplasty.5 Surgical techniques

often achieve anatomical success, but result in

associated complications such as bladder injury,

neovaginal vault granulation, introital stenosis,

vaginal discharge, urinary tract infection, or graft

infection.4 6 7 After most surgical techniques, patients

often require postoperative utilisation of a mould or

dilator.5

Despite the availability of many surgical

methods, non-surgical methods with vaginal

dilation (VD) are advocated as first-line treatment

in many instances6 8; VD has been proven effective

in the creation of a neovagina.5 9 Notably, data are

available regarding surgical creation of a neovagina

in the Chinese population10; however, there is limited

information concerning the implementation of VD in

the Chinese population, despite the recommendation

of VD as first-line treatment for the creation of a

neovagina. Chinese adolescents or their caregivers

may prefer more conservative treatment options for

MRKH syndrome.11 12 In addition, pelvic connective

tissue has been proposed to differ between Chinese

women and Caucasian women.13

In this study, we investigated the treatment

of patients with MRKH syndrome, evaluated

the effectiveness of VD therapy, and identified

complications among patients with MRKH

syndrome who underwent VD. To the best of our

knowledge, this is the first report regarding VD

therapy in Chinese women with MRKH syndrome in

the English-language medical literature.

Methods

Patient population and standard treatment

A Paediatric and Adolescent Gynaecology Clinic has

been established in our tertiary university teaching

hospital since late 2002. All female patients with

MRKH syndrome underwent treatment in that clinic

by gynaecologists who specialised in paediatric and

adolescent gynaecology. Generally, diagnosis was

made on the basis of primary amenorrhoea, normal

secondary sexual characteristics, vaginal absence, or

vaginal dimple on perineal inspection. Ultrasound

assessment showed that most patients also did

not exhibit a uterus; when a uterus was present, it

was either functioning or rudimentary. Thorough

counselling concerning the diagnosis, including

implications for future sexual life and fertility,

was provided to the patients and their caregivers.

Ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging for the

urinary system was performed to rule out urinary

tract anomalies. Patients returned for examination a

few weeks or months after the initial visit, then began

annual follow-up. During further follow-up, patients

received an explanation of vaginoplasty; they were

encouraged to discuss whether the procedure was

appropriate, following careful consideration.

Data collection

This retrospective observational study was performed

using information from a prospectively collected

database of all patients who had received treatment

for MRKH syndrome in our clinic. The patients’

medical notes were reviewed; demographic data,

presenting symptoms, previous imaging findings,

and history of sexual experience were recorded. The

method of vaginal creation, if any, was also recorded.

Regarding the outcome of VD therapy, patients

who had undergone VD as the primary method for

creation of a neovagina were included in the analysis.

The number of sessions, the starting and final vaginal

width and length, the interval until completion of

therapy, and any complications associated with

the therapy were reviewed. The outcomes of VD

in terms of sexual activity, dyspareunia, and sexual

satisfaction were reviewed.

Vaginal dilation therapy

Patients who requested VD therapy were

scheduled for individual treatment sessions with the gynaecologist. For the first session, patients

were admitted to the day ward; three intensive VD

sessions were performed on the first day. The dilator

(custom made by the Queen Charlotte and Chelsea

Hospital, United Kingdom; another dilator set, the

“Amielle Comfort vaginal dilators” manufactured

by Owen Mumford was also used) was placed at the

vaginal dimple and constant pressure was applied

using the dilator for 15 minutes. The first session

was performed by the gynaecologist, the second

session was performed by the patient under medical

supervision, and the third session was performed

independently by the patient. The patient was

discharged with instructions to perform two to three

VD sessions per day at home, 15 minutes per session.

Follow-up was arranged on an out-patient basis, at

intervals of 2 to 4 weeks. Patients were provided

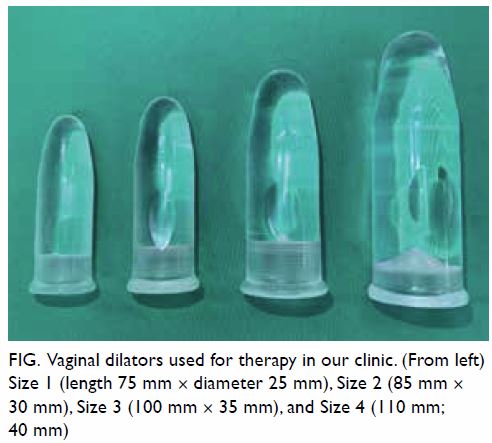

with appropriately sized dilators, typically larger

over time (Fig). Neovaginal width and length were

recorded at each follow-up visit. Any complications

and sexual function were also recorded. Vaginal

dilation therapy was discontinued when a patient

achieved satisfactory sexual intercourse.

Fig. Vaginal dilators used for therapy in our clinic. (From left) Size 1 (length 75 mm × diameter 25 mm), Size 2 (85 mm × 30 mm), Size 3 (100 mm × 35 mm), and Size 4 (110 mm; 40 mm)

Data analysis

SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 21.0 (IBM

Corp, Armonk [NY], United States) was used to

analyse the data collected. Normally distributed data

are described as mean±standard deviation, whereas

non-normally distributed data are described as

median (range). Independent samples t tests were

used to compare results between two groups. P<0.05

was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics and clinical treatment

In total, 49 patients with MRKH syndrome underwent

treatment in our clinic from 2002 to 2019. The mean patient age at presentation was 17.9±4.9 years (range,

11-36 years). Overall, 34 (69.4%) patients presented

with primary amenorrhoea and received diagnoses

of MRKH syndrome in our clinic. The mean age

among this group of patients was 16.7±2.4 years.

Another 12 (24.5%) patients were referred for further

treatment and/or VD therapy, following diagnosis in

another clinic. Two (4.1%) patients presented with

acute surgical complications, torsion of ovarian

cyst, and suspected appendicitis; the patients were

diagnosed with hematometra and hematosalpinx

at age 11 and 16 years, respectively, because of

incidental intra-operative pelvic findings. Finally,

one patient presented for labial minora hypertrophy

at age 12 years and was incidentally diagnosed with

vaginal agenesis during perineal examination. Forty

eight of the 49 patients had a 46 XX karyotype; one

patient had a 47 XXX karyotype. Two patients had

a unilateral functioning uterus, while three patients

had a non-functioning rudimentary uterine horn.

Overall, 45 patients underwent imaging, either

ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging, to assess

the renal system; some patients also underwent

intravenous urography. Of these 45 patients, 44

had normal findings; one patient had a dilated

pelvicalyceal system and ureter with suspected low

insertion into the bladder, but no signs of obstruction

were found. The remaining four patients were either

waiting for the imaging appointment or did not have

imaging information in their medical notes.

Overall, 17 (34.7%) patients underwent VD

therapy as first-line therapy for the creation of a

neovagina. Two (4.1%) patients had surgeries as

first-line treatment: one patient underwent Creatsas

vaginoplasty in our hospital and one underwent

vaginoplasty at a hospital in China. Both of these

two patients required VD therapy, at 12 years and

1 year, respectively, after their original surgeries

because of vaginal stenosis. Furthermore, five

(10.2%) patients achieved creation of a neovagina

by sexual intercourse alone. Finally, 25 (51%)

patients had not yet requested vaginoplasty; these

patients were significantly younger than patients

who had undergone vaginoplasty (22.8±5.2 years vs

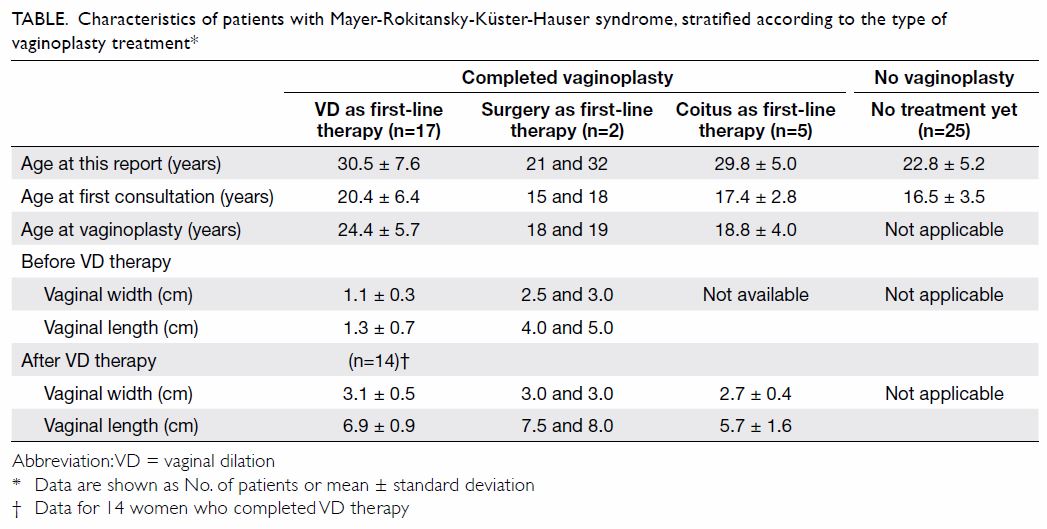

30±7.0 years, P<0.005) [Table].

Table. Characteristics of patients with Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome, stratified according to the type of vaginoplasty treatment

Vaginal dilation outcomes and follow-up

Of the 17 patients who underwent VD therapy as

first-line treatment, four (23.5%) reported that they

had previously attempted unsuccessful coitus and

therefore requested VD therapy. For these four

patients, the mean age at initiation of VD therapy

was 24.4±5.7 years (range, 18-36 years). The mean

width and length of the vagina at baseline were

1.1±0.28 cm (range, 1-2 cm) and 1.3±0.7 cm (range,

0.5-3 cm), respectively. There were no differences in

starting width and length between the four patients

who had previously attempted coitus and the remaining 13 who had not. Three patients did not

complete VD therapy because their relationships

had ended and they chose to discontinue the therapy.

Among the patients who completed VD therapy, the

final width and length of the vagina were 3.1±0.5 cm

(range, 2-4 cm) and 6.9±0.9 cm (range, 6-9 cm),

respectively. The mean interval until the completion

of VD therapy was 16±10.2 (range, 4-35) weeks.

Notably, there was no difference in duration of VD

therapy between patients who had and patients

who had not previously attempted coitus before

commencement of therapy (P=0.83).

Of the 14 patients who completed VD therapy,

one was lost to follow-up; 13 were included in further

analysis. All 13 of these patients were sexually active

after VD therapy, and 12 reported subjective sexual

satisfaction. Therefore, the success rate of VD

therapy was 92.3% in our cohort. The remaining

patient reported mild superficial dyspareunia and

that the vaginal length of 6 cm was inadequate for

achievement of sexual satisfaction; thus, surgical

vaginoplasty is planned.

Complications and subsequent therapy

The most common complication during VD was

vaginal spotting, which occurred in four (21%) of

the 19 patients who had undergone VD therapy. In

all patients, spotting subsided with conservative

management or the use of vaginal oestrogen cream.

One patient had one episode of urinary tract

infection, which resolved following treatment with

oral antibiotics.

Among the three patients in the VD group who

did not complete therapy when their relationships

ended, all began a second course of VD therapy

following new requests for treatment. The second course required a considerably shorter duration

(4-8 weeks) to achieve satisfactory vaginal length for

sexual intercourse.

Findings after neovagina creation by coitus

alone

Among the five patients who achieved creation of a

neovagina by coitus alone, their age at initial sexual

intercourse ranged from 13 to 24 years. Their mean

vaginal width and length were 2.7 cm and 5.7 cm,

respectively. One patient had a rectovaginal fistula;

she reported faecal incontinence from the vagina

and the passage of semen from the anus after sexual

intercourse. Examination revealed a 5- × 2-mm

rectovaginal fistula in the posterior vaginal wall,

3 cm above the introitus. Vaginal repair of the fistula

was performed; the patient reported no further

faecal incontinence nor abnormal passage of semen.

Findings in patients with functioning

endometrium

Regarding the two patients with a functioning

endometrium, one had a hysterectomy at age 18 years,

shortly after she had undergone Creatsas vaginoplasty.

The other patient had a unicornuate uterus that was

initially suppressed with gonadotropin-releasing

hormone analogue with supplemental oestrogen

therapy until age 21 years; she then selected uterine-preserving

surgery. After VD therapy, the patient

underwent uterovaginal anastomosis by laparotomy

and the perineal route. Two months after surgery,

she experienced an episode of cervical stenosis. The

hematometra was drained by manual dilation using

Hegar dilators at the bedside. Subsequently, she

has experienced regular monthly menstruation for

8 months postoperatively.

Discussion

In our cohort, the most common presenting

symptom was primary amenorrhoea. The patients

presented at mean age 16.7±2.4 years, which is

the appropriate time for consultation for primary

amenorrhoea. This indicated that the young women

and their caregivers did not seek to delay treatment

for this gynaecological problem. Moreover, the

healthcare providers referred the young women at

the appropriate age.

The diagnosis of MRKH syndrome is mainly

based on clinical assessment. Ultrasound can be a

useful modality to confirm the absence of a uterus

because of its relatively low cost, non-invasive nature,

and widespread availability in many gynaecology

units. However, the effectiveness of ultrasound

is operator-dependent and image quality can be

affected by each patient’s body build. Although three-dimensional

ultrasound is useful for assessment of

Müllerian anomalies,14 15 it may not be necessary to

detect the absence of a uterus. Magnetic resonance

imaging is another useful modality, with good soft

tissue resolution; it allows good visualisation of any

rudimentary horns, possible endometrium, and

ovaries. Magnetic resonance imaging reportedly

exhibited 100% sensitivity when diagnostic

laparoscopy was performed in women with uterine

anomalies14 16; therefore, diagnostic laparoscopy is

rarely required or recommended for the diagnosis

of MRKH syndrome. Even in patients with acute

hematometra of the obstructing uterus, conservative

treatment might be appropriate if the diagnosis of

MRKH syndrome is made prior to surgery. In our

cohort, a patient with acute hematometra presented

to the surgical unit and received a provisional

diagnosis of acute appendicitis. In women with

congenital androgen insensitivity syndrome, the

absence of a uterus can be a similar finding5; however,

clinical examination of women with congenital

androgen insensitivity syndrome has shown that

these patients do not have axillary hair or pubic

hair, and a simple karyotype analysis can be used to

differentiate between the two possible diagnoses.

Psychological concerns can be an important

factor in patients with MRKH syndrome. These

patients can develop a negative self-image because

they perceive themselves to be different from their

peers; they can also develop low self-esteem.17 18 19

Upon diagnosis and treatment, the patients and

their caregivers should be offered guidance and

psychological support.20 Resources should be

allocated for provision of psychological services,

which is an essential component of multidisciplinary

care. Although our service has been available for

many years, more services of this type are needed in

the future.

The creation of a neovagina is an important

aspect of treatment for patients with MRKH syndrome. Various neovagina creation techniques

have been described over the years. A non-surgical

method involving the utilisation of handheld vaginal

dilators was first described by Frank in 1938.21

Ingram22 later modified the technique with the use

of a bicycle stool. The respective success rates for

Frank’s and Ingram’s methods are reportedly 66% to

95%5 6 9 23 24 25 and 92%.22 Despite the success of these

non-surgical techniques, various surgical techniques

have also been developed for vaginoplasty. These

include the McIndoe technique, usage of various

grafts (eg, amnion, skin, or bowel), the Davydov

technique, and the Vecchietti technique. However,

these surgical techniques may result in some

complications. Following intestinal vaginoplasty,

introital stenosis and vaginal discharge can occur in

up to 9% and 7% of patients, respectively.5 7 26 27 28 There

have also been case reports regarding the onset of

adenocarcinoma in bowel grafts29 30 and the onset

of hair growth or squamous cell carcinoma in skin

grafts.31 Following the use of the Davydov technique

(ie, downward stretching of the pelvic peritoneum

to create a vagina), neovaginal vault granulation

can occur in up to 8% of patients.5 7 Intra-operative

bladder injury can occur in 1% to 2% of patients who

undergo the Vecchietti procedure, which comprises

progressive upward stretching of the perineal skin

by means of threads that exit from the anterior

abdominal wall.5 7 32 Strictures and contractures are

also a concern in patients who undergo any surgical

technique; therefore, a mould or dilation is often

required during the early postoperative period.

A relatively longer hospital stay of 2 to 9 days is a

notable concern following surgical vaginoplasty.5 7

Given its lower risk for potential complications

and high success rate, VD has become the first-line

technique for the creation of a neovagina in Australia,

the United Kingdom, the United States, and parts of

Russia.7 Previous studies have also demonstrated

that VD is more cost-effective, compared with first-line

surgical treatment.5 33

Edmonds et al9 reported an average of 5 months

to achieve satisfactory vaginal length, which they

defined as 6 cm, or when the patient is able to

achieve satisfactory sexual coitus; our results were

comparable (ie, 4 months). The mean vaginal length

of 6.9 cm achieved in our cohort was also comparable

with the findings in previous studies.7 9 23 25 Generally,

VD results in a shorter average vaginal length,

compared with surgical vaginoplasty.5 7 Notably,

6.6 cm has been proposed as the ideal vaginal length

for satisfactory sexual activity.7 24 Of the patients who

completed VD therapy in our cohort, 92.3% reported

satisfactory coitus. This success rate was comparable

to the 94.9% reported by Edmonds et al,9 who

published the largest study regarding VD thus far.

Sexual coitus has been shown to successfully

create a neovagina9 34 35; this outcome was achieved by a few patients in our cohort. Importantly,

previous coital attempts in our patients did not

affect the starting width and length of the vagina, or

the interval required to complete the dilation. This is

presumably because the patients abandoned further

coital attempts after unsuccessful coitus.

A common cause for the failure of VD is a lack

of motivation.36 The success rate was high among

patients in our cohort. Roberts et al37 reported that

women younger than 18 years of age at the initiation

of therapy had a significantly higher failure rate. The

mean age of patients in our group was 24 years; most

patients (79%) were in a relationship before initiation

of therapy (data not shown), which might have

enhanced their motivation to complete the therapy.

Accordingly, we only commence VD therapy when

patients are well prepared for this therapy, such that

they fully understand the importance of compliance.

Following the creation of a neovagina, regular

coitus or dilation is required to maintain it. Three

patients in our cohort required a second course

of VD because they experienced shrinkage of the

neovagina after discontinuation of self-dilation and

cessation of regular coitus. However, a short duration

of therapy was required to re-establish a satisfactory

neovagina. Notably, vaginal spotting occurred in

four patients during VD therapy. In all patients,

spotting resolved with conservative management

or with local application of oestrogen cream to the

neovagina.

This study demonstrated the characteristics

and treatment of Chinese patients with an

uncommon condition, MRKH syndrome, as well as

the outcome of VD therapy in those patients. The

study may have been limited by the small number of

patients, which is attributable to the rarity of MRKH

syndrome. In addition, standardised validated

questionnaires were not employed to assess sexual

function among the patients in this study. Future

research using validated questionnaires should be

performed to assess the psychological aspects of

these patients before, during, and after VD therapy.

Conclusion

Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome is

an uncommon gynaecological condition. Careful

treatment by healthcare providers familiar with

this condition may aid patients in achieving

suitable outcomes. Vaginal dilation therapy is an

effective first-line treatment for the creation of a

neovagina. The results achieved in our cohort of

Chinese women are comparable with the findings

in previously published studies in other nations.

However, long-term data collection, including the

use of validated questionnaires, will provide more

objective information regarding sexual function in

patients with MRKH syndrome.

Author contributions

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Concept or design: K Ng, SSC Chan.

Acquisition of data: K Ng, SSC Chan, KW Yiu.

Analysis or interpretation of data: K Ng, SSC Chan.

Drafting of the manuscript: K Ng, SSC Chan.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: K Ng, SSC Chan, KW Yiu.

Analysis or interpretation of data: K Ng, SSC Chan.

Drafting of the manuscript: K Ng, SSC Chan.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, JPW Chung was not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by The Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research

Ethics Committee (Ref CRE.2020.023). The requirement for

written informed consent was waived.

References

1. Creighton SM. Long-term sequelae of genital surgery.

In: Balen AH, Creighton SM, Davies MC, MacDougall

J, Stanhope R, editors. Paediatric and Adolescent

Gynaecology: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press; 2004. Crossref

2. Morcel K, Camborieux L, Programme de Recherches sur

les Aplasies Müllériennes, Guerrier D. Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis

2007;2:13. Crossref

3. Oppelt P, Renner SP, Kellermann A, et al. Clinical

aspects of Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuester-Hauser syndrome:

recommendations for clinical diagnosis and staging. Hum

Reprod 2006;21:792-7. Crossref

4. Laufer MR. Congenital absence of the vagina: in search

of the perfect solution. When, and by what technique,

should a vagina be created? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol

2002;14:441-4. Crossref

5. Callens N, De Cuypere G, De Sutter P, et al. An update

on surgical and non-surgical treatments for vaginal

hypoplasia. Hum Reprod Update 2014;20:775-801. Crossref

6. Ismail-Pratt IS, Bikoo M, Liao LM, Conway GS, Creighton

SM. Normalization of the vagina by dilator treatment

alone in complete androgen insensitivity syndrome and

Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome. Hum Reprod

2007;22:2020-4. Crossref

7. McQuillan SK, Grover SR. Dilation and surgical

management in vaginal agenesis: a systematic review. Int

Urogynecol J 2014;25:299-311. Crossref

8. Committee on Adolescent Health Care. Committee opinion

no. 562: Müllerian agenesis: diagnosis, management, and

treatment. Obstet Gynecol 2013;121:1134-7. Crossref

9. Edmonds DK, Rose GL, Lipton MG, Quek J. Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome: a review of 245

consecutive cases managed by a multidisciplinary approach

with vaginal dilators. Fertil Steril 2012;97:686-90. Crossref

10. Qin C, Luo G, Du M, et al. The clinical application of laparoscope-assisted peritoneal vaginoplasty for the

treatment of congenital absence of vagina. Int J Gynaecol

Obstet 2016;133:320-4. Crossref

11. Chan SS, Yiu KW, Yuen PM, Sahota DS, Chung TK.

Menstrual problems and health-seeking behaviour in

Hong Kong Chinese girls. Hong Kong Med J 2009;15:18-

23.

12. Yiu KW, Chan SS, Chung TK. Mothers’ attitude to the use

of a combined oral contraceptive pill by their daughters for

menstrual disorders or contraception. Hong Kong Med J

2017;23:150-7. Crossref

13. Zacharin RF. A Chinese anatomy—The pelvic supporting

tissues of Chinese and Occidental female compared and

contrasted. Aust Nz J Obstet Gyn 1977;17:1-11. Crossref

14. Deutch TD, Abuhamad AZ. The role of 3-dimensional

ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the

diagnosis of Mullerian duct anomalies: a review of the

literature. J Ultrasound Med 2008;27:413-23. Crossref

15. Ahmadi F, Haghighi H. Detection of congenital Mullerian

anomalies by real-time 3D sonography. J Reprod Infertil

2012;13:65-6.

16. Pellerito JS, McCarthy SM, Doyle MB, Glickman MG,

DeCherney AH. Diagnosis of uterine anomalies: relative

accuracy of MR imaging, endovaginal sonography, and

hysterosalpingography. Radiology 1992;183:795-800. Crossref

17. Heller-Boersma JG, Edmonds DK, Schmidt UH. A

cognitive behavioural model and therapy for utero-vaginal

agenesis (Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome:

MRKH). Behav Cogn Psychother 2009;37:449-67. Crossref

18. Heller-Boersma JG, Schmidt UH, Edmonds DK.

Psychological distress in women with uterovaginal agenesis

(Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser Syndrome, MRKH).

Psychosomatics 2009;50:277-81. Crossref

19. Patterson CJ, Crawford R, Jahoda A. Exploring the

psychological impact of Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-

Hauser syndrome on young women: an interpretative

phenomenological analysis. J Health Psychol 2016;21:1228-

40. Crossref

20. Wagner A, Brucker SY, Ueding E, et al. Treatment

management during the adolescent transition period of

girls and young women with Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-

Hauser syndrome (MRKHS): a systematic literature review.

Orphanet J Rare Dis 2016;11:152. Crossref

21. Frank R. The formation of an artificial vagina without

operation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1938;35:1053-5. Crossref

22. Ingram JM. The bicycle seat stool in the treatment of

vaginal agenesis and stenosis: a preliminary report. Am J

Obstet Gynecol 1981;140:867-73. Crossref

23. Bach F, Glanville JM, Balen AH. An observational study of

women with Mullerian agenesis and their need for vaginal

dilator therapy. Fertil Steril 2011;96:483-6. Crossref

24. Callens N, De Cuypere G, Wolffenbuttel KP, et al. Long-term

psychosexual and anatomical outcome after vaginal dilation or vaginoplasty: a comparative study. J Sex Med

2012;9:1842-51. Crossref

25. Ketheeswaran A, Morrisey J, Abbott J, Bennett M, Dudley J,

Deans R. Intensive vaginal dilation using adjuvant

treatments in women with Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome: retrospective cohort study. Aust N Z J

Obstet Gynaecol 2018;58:108-13. Crossref

26. Kölle A, Taran FA, Rall K, Schöller D, Wallwiener D,

Brucker SY. Neovagina creation methods and their

potential impact on subsequent uterus transplantation: a

review. BJOG 2019;126:1328-35. Crossref

27. Cai B, Zhang JR, Xi XW, Yan Q, Wan XP. Laparoscopically

assisted sigmoid colon vaginoplasty in women with Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome: feasibility and

short-term results. BJOG 2007;114:1486-92. Crossref

28. Darai E, Toullalan O, Besse O, Potiron L, Delga P. Anatomic

and functional results of laparoscopic-perineal neovagina

construction by sigmoid colpoplasty in women with

Rokitansky’s syndrome. Hum Reprod 2003;18:2454-9. Crossref

29. Hiroi H, Yasugi T, Matsumoto K, et al. Mucinous

adenocarcinoma arising in a neovagina using the sigmoid

colon thirty years after operation: a case report. J Surg

Oncol 2001;77:61-4. Crossref

30. Kita Y, Mori S, Baba K, et al. Mucinous adenocarcinoma

emerging in sigmoid colon neovagina 40 years after its

creation: a case report. World J Surg Oncol 2015;13:213. Crossref

31. Idrees MT, Deligdisch L, Altchek A. Squamous papilloma

with hyperpigmentation in the skin graft of the neovagina

in Rokitansky syndrome: literature review of benign and

malignant lesions of the neovagina. J Pediatr Adolesc

Gynecol 2009;22:e148-55. Crossref

32. Brucker SY, Gegusch M, Zubke W, Rall K, Gauwerky JF,

Wallwiener D. Neovagina creation in vaginal agenesis:

development of a new laparoscopic Vecchietti-based

procedure and optimized instruments in a prospective

comparative interventional study in 101 patients. Fertil

Steril 2008;90:1940-52. Crossref

33. Routh JC, Laufer MR, Cannon GM Jr, Diamond DA,

Gargollo PC. Management strategies for Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser related vaginal agenesis: a cost-effectiveness

analysis. J Urol 2010;184:2116-21. Crossref

34. D’Alberton A, Santi F. Formation of a neovagina by coitus.

Obstet Gynecol 1972;40:763-4. Crossref

35. Moen MH. Creation of a vagina by repeated coital

dilatation in four teenagers with vaginal agenesis. Acta

Obstet Gynecol Scand 2000;79:149-50. Crossref

36. Liao LM, Doyle J, Crouch NS, Creighton SM. Dilation

as treatment for vaginal agenesis and hypoplasia: a pilot

exploration of benefits and barriers as perceived by

patients. J Obstet Gynaecol 2006;26:144-8. Crossref

37. Roberts CP, Haber MJ, Rock JA. Vaginal creation for

Mullerian agenesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001;185:1349-52. Crossref