Hong Kong Med J 2021 Apr;27(2):106–12 | Epub 25 Mar 2021

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Behavioural insights and attitudes on community

masking during the initial spread of COVID-19 in Hong Kong

Victor CW Tam1, SY Tam1, ML Khaw2, Helen KW Law1, Catherine PL Chan3, Shara WY Lee1

1 Department of Health Technology and Informatics, Faculty of Health and Social Sciences, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong

2 Tasmanian School of Medicine, University of Tasmania, Hobart Tasmania 7001, Australia

3 Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Shara WY Lee (shara.lee@polyu.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Community face mask use during the

coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has

considerably differed worldwide. Generally, Asians

are more inclined to wear face masks during disease

outbreaks. Hong Kong has emerged relatively

unscathed during the initial outbreak of COVID-19, despite its dense population. Previous infectious

disease outbreaks influenced the local masking

behaviour and response to public health measures.

Thus, local behavioural insights are important for

the successful implementation of infection control

measures. This study explored the behaviour and

attitudes of wearing face masks in the community

during the initial spread of COVID-19 in Hong

Kong.

Methods: We observed the masking behaviour of

10 211 pedestrians in several regions across Hong

Kong from 1 to 29 February 2020. We supplemented

the data with an online survey of 3199 respondents’

views on face mask use.

Results: Among pedestrians, the masking rate

was 94.8%; 83.7% wore disposable surgical masks.

However, 13.0% wore surgical masks incorrectly with

42.5% worn too low, exposing the nostrils or mouth;

35.5% worn ‘inside-out’ or ‘upside-down’. Most

online respondents believed in the efficacy of wearing

face mask for protection (94.6%) and prevention of community spread (96.6%). Surprisingly, 78.9%

reused their mask; more respondents obtained

information from social media (65.9%) than from

government websites (23.2%).

Conclusions: In Hong Kong, members of the

population are motivated to wear masks and believe

in the effectiveness of face masks against disease

spread. However, a high mask reuse rate and errors

in masking techniques were observed. Information

on government websites should be enhanced and

their accessibility should be improved.

New knowledge added by this study

- A high mask reuse rate was observed during the initial spread of coronavirus disease 2019 in Hong Kong.

- Masking errors were observed among 13.0% of the pedestrians wearing surgical masks in this study, while mask reuse was reported by 78.9% of respondents in an online survey.

- Although official government websites were regarded as reliable, they were less popular than social media for the acquisition of health-related information.

- Increased efforts are needed to educate the general public regarding the correct use and handling of masks.

- Manufacturers are encouraged to provide clear instructions on their packaging and print a symbol on each mask to prevent users from wearing masks inside-out.

- Because of the popularity of social media, authorities should utilise these platforms as a supplement to their standard websites for better public exposure and communication concerning health-related information.

Introduction

The rapid and devastating spread of the coronavirus

disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caught the

global community unprepared and overwhelmed

the disease control measures of many nations.

Measures deployed in Hong Kong to control the spread of COVID-19 were less stringent than those

adopted in other nations; however, they proved to be

effective.1 Territory-wide lockdowns, curfews, and

the controversial surveillance of smartphone data for

contact tracing purposes were all avoided. A recent

local study showed that behavioural changes were the key factors associated with limiting the spread of

COVID-19 and seasonal influenza.1

Community masking by healthy individuals

is controversial and opinions on its effectiveness or

necessity differ among health authorities worldwide.2

Since the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)

epidemic in 2003, the population of Hong Kong

has maintained a strong masking culture. Although

masking in crowded areas has always been voluntary

in Hong Kong, rates of 61% and 79% during the SARS

outbreak were recorded in two previous studies.3 4 In

the present study, we aimed to explore the masking

behaviour of pedestrians in crowded areas, as well

as the attitude of the population towards community

masking, during the initial spread of COVID-19 in

Hong Kong.

Methods

Study design

This study protocol was approved by the Human

Subjects Ethics Application Review board of The

Hong Kong Polytechnic University and complied with

the Declaration of Helsinki. The Strengthening the

Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

(STROBE) checklist for cross-sectional studies was

implemented in the drafting of this article. The study

protocol consisted of two parts: an observational

study (Part 1) and an online survey (Part 2).

Part 1: Observational study approach

The masking behaviour of pedestrians in Hong Kong

was observed between 1 and 29 February 2020.

Eleven well-populated locations across Hong Kong

were selected for observation. Observation sites on

the main street of each location were chosen based

on pedestrian throughput, and the ability to observe

pedestrians in a clear, unhindered manner without

interrupting the flow of traffic. Three observation

sessions per day were conducted at 12:00-14:30

(lunch time), 14:30-17:00 (afternoon), and 17:00-19:30 (evening). To reduce selection bias, the location

and observation times were randomly preselected

on the evening before each study by drawing two sets

of shuffled opaque envelopes containing the session

time and locations.

On days with sufficient rain to warrant

umbrella use, further observations were terminated.

The data collected until the occurrence of rain were

included for analysis. One observer was allocated to

each session and the following data were collected:

frequency of masking, type of mask worn, and

number and type of erroneous masking practices.

Only pedestrians walking in one direction were

observed to prevent duplicate counting. The criteria

for seven common types of masking errors were

based on deviations from the surgical mask use

guidelines published by the Hong Kong Centre for

Health Protection.5 The definitions for masking errors were standardised before the study by

consensus among the observers after a field test.

Part 2: Online survey approach

Members of the Hong Kong population were

included in an online survey of behaviour and views

on community masking, which was conducted

between 23 March and 14 April 2020. Consent

was implied in the voluntary participation and

completion of the survey. Personal information was

not collected; however, demographic details (eg, age,

gender, education level, and whether the respondents

were healthcare students or professionals [HCSPs])

were recorded. Short-term visitors were excluded by

targeting only respondents who had lived in Hong

Kong for the preceding 6 months.

A link to the online survey was distributed

via various means such as social media and email.

The survey required approximately 5 minutes to

complete. A 5-point Likert scale was used to grade

respondents’ perceptions of mask efficacy for

protection and the prevention of community spread,

evaluation of mask performance, and confidence in

mask selection and correct use of mask. Respondents

were also asked about mask reuse habits and storage,

and information sources for COVID-19–related

health matters, including their perceived reliability

of those sources. A sample questionnaire is shown in

the online supplementary Appendix.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by an independent

statistician using IBM SPSS Statistics (Windows

version 21.0, IBM Corp. Armonk [NY], United

States). Univariate logistic regression and univariate

ordinal regression were used to explore associations

with binary and ordinal outcomes, respectively.

Crude odds ratios (ORs) for each demographic

variable were calculated from univariate analysis.

Multivariate regression analyses were then

performed, including all demographic variables, and

the adjusted OR was estimated for each demographic

variable. Descriptive statistics were used to provide

an overview of the observations; the findings of

regression analysis were presented as ORs and 95%

confidence intervals (CIs). A P value of <0.05 was

considered statistically significant.

Results

Part 1: Observational study

In total, 10 211 pedestrians were observed over

25 sessions. The masking rate was 94.8%; most

pedestrians wore disposable surgical masks (83.7%),

and a small number wore N95 respirators (0.7%).

The remaining pedestrians wore an assortment of

face masks made of fabric or neoprene rubber; a few

wore gas masks.

Among pedestrians wearing surgical masks,

masking errors were observed in 1113 (13.0%)

individuals (Table 1). The most common errors

observed included: mask worn too low, exposing the

nostrils and mouth (42.5%), or mask worn inside-out/upside-down (35.5%). A less common but

serious error was the absence of hand hygiene after

touching their masks (16.4%).

Part 2: Online survey

A total of 3199 respondents completed the survey.

Data from 74 non-residents were excluded, and the

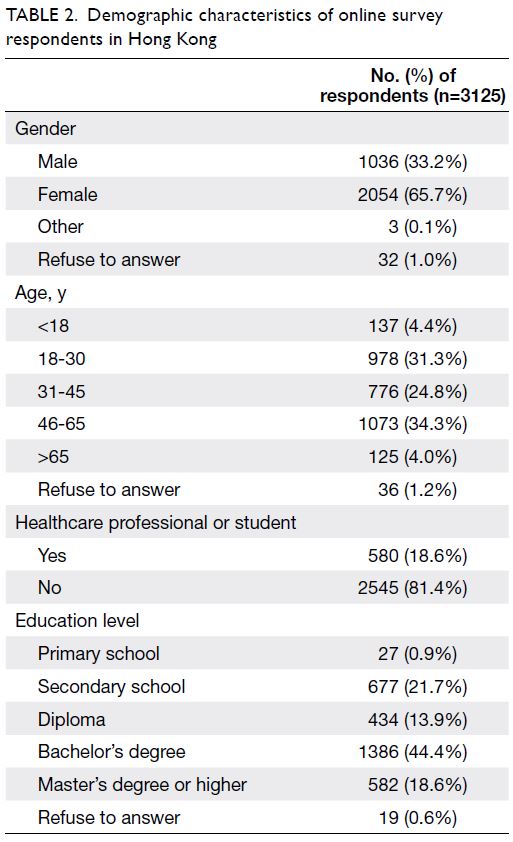

remaining 3125 responses were analysed. Female respondents comprised a larger proportion (65.7%),

education status was at diploma level or above for

76.9% of the respondents, and 18.6% were HCSPs

(Table 2).

Views on face mask performance

Most online respondents were confident of using

a face mask correctly (96.9%) and believed in its

efficacy for protection (94.6%) and the prevention

of community spread (96.6%). Most respondents

indicated that they clearly understood the functions

of the different types of masks available (83.6%) and

were confident of their ability to evaluate those masks

(77.1%). Multivariate ordinal regression analyses

showed that HCSPs were associated with greater

confidence (OR=1.62; 95% CI=1.34-1.95; P<0.001)

of using a face mask correctly; while increasing age

was associated with lower confidence (OR=0.87;

95% CI=0.81-0.94; P<0.001 for each successive age-group).

However, no significant associations were

found with education level or gender.

Reuse of mask

In all, 78.9% of the respondents reused their face

masks and stored them using a variety of methods: between tissue papers (74.1%), in paper envelopes

(46.5%), in plastic bags (22.9%), left on table

(6.5%), and in plastic containers (6.0%) [Table 3].

Multivariate logistic regression analyses concerning

reuse of face masks showed greater likelihood among

respondents with higher education level (OR=1.14;

95% CI=1.05-1.24; P=0.003 for each successive

education level), older age (OR=1.48; 95% CI=1.35-1.62;

P<0.001 for each successive age-group), and HCSP status (OR=1.61; 95% CI=1.26-2.07; P<0.001). Gender was not associated with mask reuse.

Sources of health information

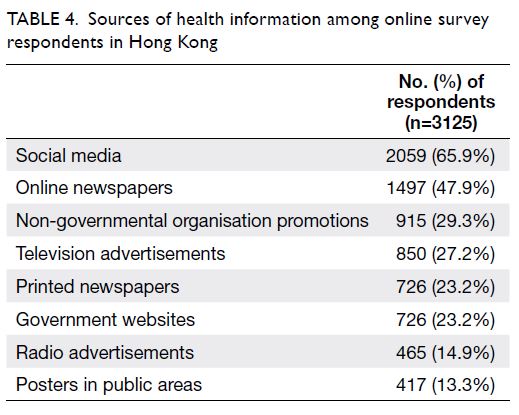

More respondents reported the acquisition of

information on mask usage via social media (65.9%)

and online newspapers (47.9%), compared with

official government websites (23.2%) [Table 4].

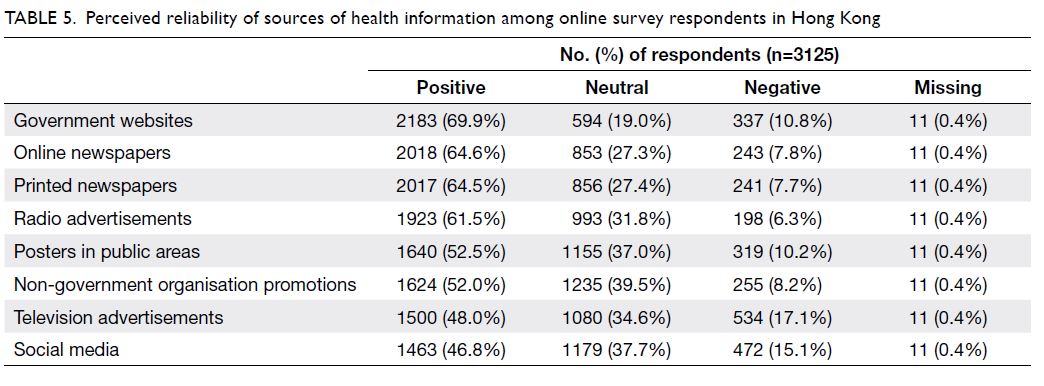

Ratings for reliability were highest for government

websites (69.9%), followed by online (64.6%) and

printed (64.5%) newspapers (Table 5).

Table 5. Perceived reliability of sources of health information among online survey respondents in Hong Kong

Subanalysis of healthcare students or

professionals

Compared with other respondents, HCSPs had a

better understanding of mask types and indications

for each type (multivariate ordinal regression:

OR=1.93; 95% CI=1.60-2.34; P<0.001). They were

more likely to choose surgical masks (multivariate

logistic regression: OR=2.43; 95% CI=1.04-5.72;

P=0.041) and less likely to choose N95 respirators

(OR=0.54; 95% CI=0.44-0.68; P<0.001) for

community use. They were also more likely to reuse

their face masks (OR=1.61; 95% CI=1.26-2.07;

P<0.001) and store them between tissues (OR=1.80;

95% CI=1.47-2.21; P<0.001), but less likely to use

paper envelopes (OR=0.80; 95% CI=0.65-0.98;

P=0.030).

Discussion

Our study investigated pedestrian mask use and

public perceptions of community masking during

the initial spread of COVID-19 in Hong Kong. The

masking rate was high, and the public was confident

in mask efficacy for protection and the prevention

of community spread. Most pedestrians wore a

surgical mask, but a small proportion of these masks

were worn incorrectly. Surprisingly, the mask reuse

rate was high, and varying methods were used

for storage. Although government websites were

considered reliable, social media was more popular

as the source of information regarding masking and

health-related matters.

Face mask use in Hong Kong: general

perceptions and behaviours

Population-level behavioural insights are essential

for coordinating an effective and coherent

infection control strategy.6 Previous events and

disease outbreaks have considerably influenced

the masking culture in Hong Kong. Similar to

covering up when coughing or sneezing, wearing a

mask in the community or workplace when unwell

became a part of recent social etiquette following

the SARS outbreak. During the SARS epidemic,

a public hospital became a source of community

spread, prompting the government to enforce and promote community protective behaviour

thereafter, particularly in public hospitals. These

efforts included strong recommendations for

hospital visitors to wear masks, as well as the

widespread availability of hand sanitisers in strategic

areas. Whilst evidence supporting these practices

remains controversial, these recommendations have

positively influenced the attitude and behaviour of

the general public towards mass masking and hand

hygiene for protection during disease outbreaks.

These events may explain the high voluntary

masking rate that we have recorded in this study. A

high masking rate was also previously noted during

the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong.2 3 Notably, face

masks are also commonly used to protect against

air pollution, particularly during hazy weather and

within high traffic areas.

The issue of community masking was

controversial particularly during the early stages

of the COVID-19 pandemic, such that conflicting

recommendations were issued by various health

authorities and public figures worldwide. At the

time of this study, the World Health Organization

recommended against community masking because

of insufficient evidence regarding its effectiveness,

the potential for a false sense of security, and the

stressed supply of surgical masks for hospital use.7

However, this stance on effectiveness should have

been considered in the context of clinical outcome

studies,8 which were based largely on the spread of

influenza and would not necessarily be applicable to

the spread of COVID-19. Furthermore, reports of

disease spread involving pre-symptomatic carriers

of COVID-19 were not considered.

Although the surgical mask was originally

designed for the protection of patients during

surgery, its role in reducing wound infection is not

fully established and has been contentious.9 The

rationale for masking later shifted to protection

for the wearer, although evidence to support this

perspective is equally tenuous.10 Under standardised

simulated conditions, laboratory studies have shown that surgical masks are effective in limiting both

inbound and outbound transmission of aerosol

particles.11 Thus, wearing a face mask will limit the

spread of droplets during coughing or sneezing from

both symptomatic and asymptomatic carriers; it will

also protect the mucosa of the nostrils and mouth of

the wearer from droplets and aerosols.12 Contrary to

the claims by the World Health Organization7 that

wearing a mask may create a false sense of security

leading to the abandonment of other protective

behaviours, voluntary mask use in crowded areas

was shown to encourage protective behaviour and

performance of hand hygiene.13 The high masking

rate in Hong Kong may be an intangible factor

that enabled indirect control of community spread

by preventing viral shedding from asymptomatic

carriers. Multiple clusters of infections have

occurred in locations with poor masking or social

distancing,14 15 suggesting that these measures are

important. Since April 2020, the World Health

16 has updated its guidelines to

recommend the use of non-medical masks among

the general public when there is a limited capacity to

implement other containment measures.

Errors, reuse, and storage

A substantial proportion of pedestrians (13.0%) wore

their surgical face masks incorrectly, which may have

limited the protective efficacy of these masks. Most

commonly, they were worn too low, ‘upside-down’

or ‘inside-out’. A surgical mask consists of an inner

water-absorbing layer and an outer water-repelling

filter, which are horizontally pleated to create rows

of gutters for expansion and to catch moisture. A

mask worn inside-out accumulates moisture on the

facial side, which is uncomfortable. This increases

the likelihood that users will touch and rub their

faces, leading to self-contamination or temporary

mask removal. Additionally, a mask worn inside-out

may trap droplets from surrounding people

within the outward-facing water-absorbing layer. A

mask worn too low on the face exposes the nostrils or mouth, which are mucosal surfaces vulnerable

to droplets and airborne contamination. Although

unlikely, this error may arise from semantics—the

Chinese term for ‘face mask’ literally means ‘mouth

cover’, which may have misled users into believing

that this type of coverage was its sole purpose. We

examined the packaging of various brands of surgical

masks sold locally and found that very few provided

instructions for correct use. Instructions were

previously considered unnecessary because surgical

masks were intended for use by HCSPs; however,

many users now are members of the general public.

Manufacturers are encouraged to provide clear

instructions on their packaging and print a symbol

on each mask to prevent users from wearing masks

inside-out.

We were alarmed by the high reuse rate of

disposable masks. Some reasons were obvious, such

as a supply shortage, compounded by panic buying

that leads to price inflation. However, the masking

rate might have been lower if the masks were not

reused. Many users were probably aware that the

masks should not be reused, but our findings should

serve as a ‘reality check’.17 Surprisingly, mask reuse

was more common among HCSPs; this may have

been related to greater confidence in their ability

to handle a potentially contaminated mask, as well

as the belief that the causative virus (severe acute

respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) will degrade on

non-living surfaces over time.18 Although there is no

evidence of increased disease spread, the potential

for contamination from poor handling is obvious.

Various mask storage methods, such as within

tissue papers, in paper envelopes, in plastic bags,

and in containers, were described. Recent evidence

suggests that the severe acute respiratory syndrome

coronavirus 2, which causes COVID-19, is more

stable on smooth non-porous surfaces; thus, it may

be safer to store masks in paper material (eg, tissues

or envelopes) where it will dry effectively.18 19 It has

also been reported that the virus can be inactivated

at 70°C in approximately 5 to 30 minutes.18 20 This

information will be useful should the reuse of

surgical masks be necessary during an exceptional

shortage; moreover, input from infectious disease

experts on the appropriate handling techniques is

likely to provide considerable value. Recently, Hong

Kong residents were issued reusable face masks with

antimicrobial properties for community use.19 21

Despite the high cost of such masks, this may be

the solution to face mask shortage issues; it may

also preserve medical face masks for hospital use, as

recommended by the World Health Organization.16

Sources of information regarding face masks

Social media was the most common source of health

information but was regarded as the least reliable

source. Although official government websites were regarded as the most reliable sources, many

respondents chose convenience over perceived

reliability when sourcing health information.

However, the potential for misinformation is an

important concern and conflicting advice may create

distrust, thereby interfering with the establishment

of a coherent response to the pandemic. Because

of the popularity of social media, authorities

should utilise these platforms as a supplement to

their standard websites for better public exposure

and communication concerning health-related

information. There is a clear need to address the

issues that we have identified. Correct masking

technique will reduce wastage and prevent self-contamination

through mishandling.

Limitations

There were several limitations to this study. First,

because of its observational nature, we were unable

to determine why some pedestrians did not wear

masks (eg, whether this was related to availability

or choice). Second, our findings may not be

sufficiently representative of other less crowded

areas in Hong Kong. Third, the respondents to our

online survey were limited to those with internet

access, which might have prevented inclusion of

individuals who were older, less educated, or more

vulnerable. Telephone and face-to-face interviews

may provide sufficient data concerning older people

and individuals with low socio-economic status.

Lastly, we did not identify the respondents of our

survey; thus, multiple responses could have been

submitted by some users. Nevertheless, this is the

largest behavioural study thus far to explore some of

the issues on the use of face masks during the initial

spread of COVID-19 in Hong Kong.

Conclusion

This study provided behavioural insights and

attitudes on community masking in a region that has

successfully managed the initial spread of COVID-19 through a combination of public health and

behavioural interventions. Members of the Hong

Kong population are highly motivated to engage in

masking practices and believe in its effectiveness

for protection and the prevention of disease spread.

However, a high face mask reuse rate and incorrect

masking techniques were observed. Information on

government websites should be enhanced and linked

to social media to improve accessibility and provide

suitable guidance for the general public.

Author contributions

Concept or design: VCW Tam, CPL Chan, HKW Law, SWY Lee.

Acquisition of data: VCW Tam, HKW Law, SWY Lee.

Analysis or interpretation of data: VCW Tam, SWY Lee.

Drafting of the manuscript: VCW Tam, SY Tam, ML Khaw, SWY Lee.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: VCW Tam, HKW Law, SWY Lee.

Analysis or interpretation of data: VCW Tam, SWY Lee.

Drafting of the manuscript: VCW Tam, SY Tam, ML Khaw, SWY Lee.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank Miss Abbie Chan, Department of Health Technology

and Informatics, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, for

her assistance in data collection throughout the study; Mr Alex

Nicol for his professional advice with manuscript preparation

and statistical analysis; and Dr Wai-kwong Poon for his expert

advice with research design and manuscript revision.

Declaration

A letter reporting preliminary findings of part of the present

study was published in Tam VC, Tam SY, Poon WK, Law

HK, Lee SW. A reality check on the use of face masks during

the COVID-19 outbreak in Hong Kong. EClinicalMedicine.

2020 Apr 24;22:100356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100356

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Human Subjects Ethics Application Review Board of Hong Kong Polytechnic

University (Ref HSEARS20200213002-01). Participation

in the survey was voluntary, and consent was implied from

completion of the survey.

References

1. Cowling BJ, Ali ST, Ng TW, et al. Impact assessment of

non-pharmaceutical interventions against coronavirus

disease 2019 and influenza in Hong Kong: an observational

study. Lancet Public Health 2020;5:e279-88. Crossref

2. Cheng KK, Lam TH, Leung CC. Wearing face masks in the

community during the COVID-19 pandemic: altruism and

solidarity. Lancet 2020 Apr 16. Epub ahead of print. Crossref

3. Leung GM, Quah S, Ho LM, et al. A tale of two cities:

community psychobehavioral surveillance and related

impact on outbreak control in Hong Kong and Singapore

during the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic.

Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2004;25:1033-41. Crossref

4. Tang CS, Wong CY. Factors influencing the wearing

of facemasks to prevent the severe acute respiratory

syndrome among adult Chinese in Hong Kong. Prev Med

2004;39:1187-93. Crossref

5. Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health,

Hong Kong SAR Government. Use mask properly. 2015. Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/use_mask_properly.pdf. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

6. Sadique MZ, Edmunds WJ, Smith RD, et al. Precautionary

behavior in response to perceived threat of pandemic

influenza. Emerg Infect Dis 2007;13:1307-13. Crossref

7. World Health Organization. Advice on the use of masks

in the context of COVID-19: interim guidance. 5 June

2020. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/332293/WHO-2019-nCov-IPC_Masks-2020.4-eng.pdf. Accessed 5 Jun 2020.

8. Orr NW. Is a mask necessary in the operating theatre? Ann

R Coll Surg Engl 1981;63:390-2.

9. Romney MG. Surgical face masks in the operating theatre: re-examining the evidence. J Hosp Infect 2001;47:251-6. Crossref

10. Lipp A. The effectiveness of surgical face masks: what the literature shows. Nurs Times 2003;99:22-4.

11. van der Sande M, Teunis P, Sabel R. Professional and home-made

face masks reduce exposure to respiratory infections

among the general population. PloS One 2008;3:e2618. Crossref

12. Leung NH, Chu DK, Shiu EY, et al. Respiratory virus

shedding in exhaled breath and efficacy of face masks. Nat

Med 2020;26:676-80. Crossref

13. Wada K, Oka-Ezoe K, Smith DR. Wearing face masks

in public during the influenza season may reflect other

positive hygiene practices in Japan. BMC Public Health

2012;12:1065. Crossref

14. Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong

Kong SAR Government. CHP investigates 10 additional

cases of novel coronavirus infection. 2020. Updated 9

Feb 2020. Available from: https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202002/09/P2020020900704p.htm. Accessed 20

Mar 2020.

15. Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong

Kong SAR Government. CHP investigates 43 additional

cases of COVID-19. 2020. Updated 26 Mar 2020. Available

from: https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202003/26/P2020032600765p.htm. Accessed 10 Apr 2020.

16. World Health Organization. Advice on the use of masks

in the community, during home care and in health care

settings in the context of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)

outbreak: interim guidance, 29 January 2020. Available

from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/330987. Accessed 17 Aug 2020.

17. Tam VC, Tam SY, Poon WK, Law HK, Lee SW. A

reality check on the use of face masks during the

COVID-19 outbreak in Hong Kong. EClinicalMedicine

2020;22:100356. Crossref

18. Chin AW, Chu JT, Perera MR, et al. Stability of SARS-CoV-2

in different environmental conditions. Lancet Microbe

2020;1:e10. Crossref

19. van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, et al. Aerosol

and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with

SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1564-7. Crossref

20. Nathan N. Waste not, want not: re-usability of N95 masks. Anesth Analg 2020;131:3. Crossref

21. Hong Kong SAR Government. Government to distribute

free reusable masks to all citizens. 2020. Updated 5 May

2020. Available from: https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202005/05/P2020050500692.htm. Accessed 3 Aug

2020.