Hong Kong Med J 2021 Apr;27(2):113–7 | Epub 15 Nov 2020

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Effect of COVID-19 on delivery plans and

postnatal depression scores of pregnant women

PW Hui, MD, FRCOG; Grace Ma, MHSM (Health Services Management); Mimi TY Seto, MB, BS, MRCOG; KW Cheung, MB, BS, MRCOG

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr PW Hui (apwhui@hku.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Owing to the coronavirus disease

2019 outbreak Hong Kong hospitals have suspended

visiting periods and made mask wearing mandatory.

In obstetrics, companionship during childbirth has

been suspended and prenatal exercises, antenatal

talks, hospital tours, and postnatal classes have

been cancelled. The aim of the present study was to

investigate the effects of these restrictive measures

on delivery plans and risks of postpartum depression.

Methods: We compared pregnancy data and the

Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS)

scores of women who delivered between the

pre-alert period (1 Jan 2019 to 4 Jan 2020) and

post-alert period (5 Jan 2020 to 30 Apr 2020) in a

tertiary university public hospital in Hong Kong.

Screening for postpartum depression was performed

routinely using the EPDS questionnaire 1 day and

within 1 week after delivery.

Results: There was a 13.1% reduction in the number

of deliveries between 1 January and 30 April from

1144 in 2019 to 994 in 2020. The EPDS scores were

available for 4357 out of 4531 deliveries (96.2%). A

significantly higher proportion of women had EPDS

scores of ≥10 1 day after delivery in the post-alert group than the pre-alert group (14.4% vs 11.9%;

P<0.05). More women used pethidine (6.2% vs 4.6%)

and fewer used a birthing ball (8.5% vs 12.4%) for

pain relief during labour in the post-alert group.

Conclusions: Pregnant women reported more

depressive symptoms in the postpartum period

following the alert announcement regarding

coronavirus infection in Hong Kong. This was

coupled with a drop in the delivery rate at our public

hospital. Suspension of childbirth companionship

might have altered the methods of intrapartum pain

relief and the overall pregnancy experience.

New knowledge added by this study

- The delivery rate at a public hospital was reduced during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

- Women who delivered in the public hospital had higher Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale scores during the coronavirus alert period.

- A lower rate of non-pharmacological pain relief and a higher rate of pethidine usage were observed during labour.

- Obstetricians should be aware of the psychological burden of the COVID-19 outbreak on pregnant women, especially in the immediate postpartum period.

- Alternative measures and effective intervention should be available to support these women during this pandemic crisis.

Introduction

The outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19) leads to a declaration of a serious level

of response on 4 January 2020, which was escalated

to the emergency level on 25 January 2020.1 2

Corresponding policies were imposed by the Hospital

Authority at that time. Visiting periods were

suspended, and mask wearing became mandatory

in hospitals. In obstetrics, companionship during

childbirth was stopped, as were visits to newborns

staying with mothers in the postnatal ward. All prenatal exercise, antenatal talks, hospital tours,

and postnatal classes were cancelled. The infection

continued to spread worldwide, and a pandemic

was declared by the World Health Organization on

11 March 2020. The first case of a COVID-19-infected

pregnant mother was confirmed on 20 March 2020.

The Hong Kong Government has further restricted

travel and tightened social distancing and other

measures to limit the spread of COVID-19.

Increased psychological stress and anxiety

levels have been reported in countries with major outbreaks.3 4 As reflected by the Edinburgh Postnatal

Depression Scale (EPDS), pregnant women assessed

after the declaration of the COVID-19 epidemic had

significantly higher rates of depressive symptoms

than women assessed before the announcement

in China.5 6 Behavioural changes have also been

recognised among pregnant women.7 This evolving

situation and its concomitant alterations in obstetric

care can potentially pose extra psychological stress

during the peripartum period.

In our university-affiliated tertiary hospital in

Hong Kong, screening for women at risk of or having

emotional problems is performed for all pregnancies

antenatally during a booking visit. Counselling

and support are provided by trained midwives and

nurses from Comprehensive Child Development

Service to those in need. Postpartum depression is

routinely assessed after delivery using the validated

EPDS.8 9 The aim of the present study was to examine

the effect of COVID-19 and its concurrent service

adjustments on couples’ obstetric planning and

postpartum depression.

Methods

This was a retrospective study of the delivery data

and EPDS scores of women who delivered at Queen

Mary Hospital in Hong Kong from 1 January 2019

to 30 April 2020. Information related to the original

number of bookings, actual deliveries, childbirth

companionship, basic demographics, mode of delivery, epidural rate, and other methods of pain

relief were retrieved from the Clinical Information

System and Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting

System of the Hospital Authority.

Screening for postpartum depression was

performed routinely by asking all women to complete

the EPDS questionnaire 1 day after delivery.

This assessment was conducted again by phone

within 1 week after delivery. The EPDS consists of

10 questions with a maximum score of 30 and has

a validated Chinese version.9 10 A cut-off of ≥10

was adopted locally. Women with high scores were

counselled by a dedicated team of midwives and

psychiatric nurses.

Comparisons of delivery data and EPDS scores

were performed between women who delivered

during the pre-alert period (1 Jan 2019 to 4 Jan 2020)

and the post-alert period (5 Jan 2020 to 30 Apr 2020).

Analysis was performed using SPSS (Windows

version 25; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States).

Student’s t tests and Chi squared tests were used as

appropriate with P<0.05 considered as statistically

significant.

Results

There were 1997 pregnant women with expected

delivery dates between January 2020 and April 2020

booked for delivery at Queen Mary Hospital, as

compared with 1869 bookings for the corresponding

4-month period in 2019. However, there was a

13.1% reduction in the number of actual deliveries

between 1 January and 30 April, from 1144 in 2019

to 994 in 2020. Fewer than half of the total number

of women who originally booked for delivery in our

hospital eventually delivered there, and the drop was

more profound from February to April 2020. As a

result, there were 3577 deliveries from 1 January

2019 to 4 January 2020 (ie, the pre-alert group) and

954 deliveries from 5 January 2020 to 30 April 2020

(ie, the post-alert group).

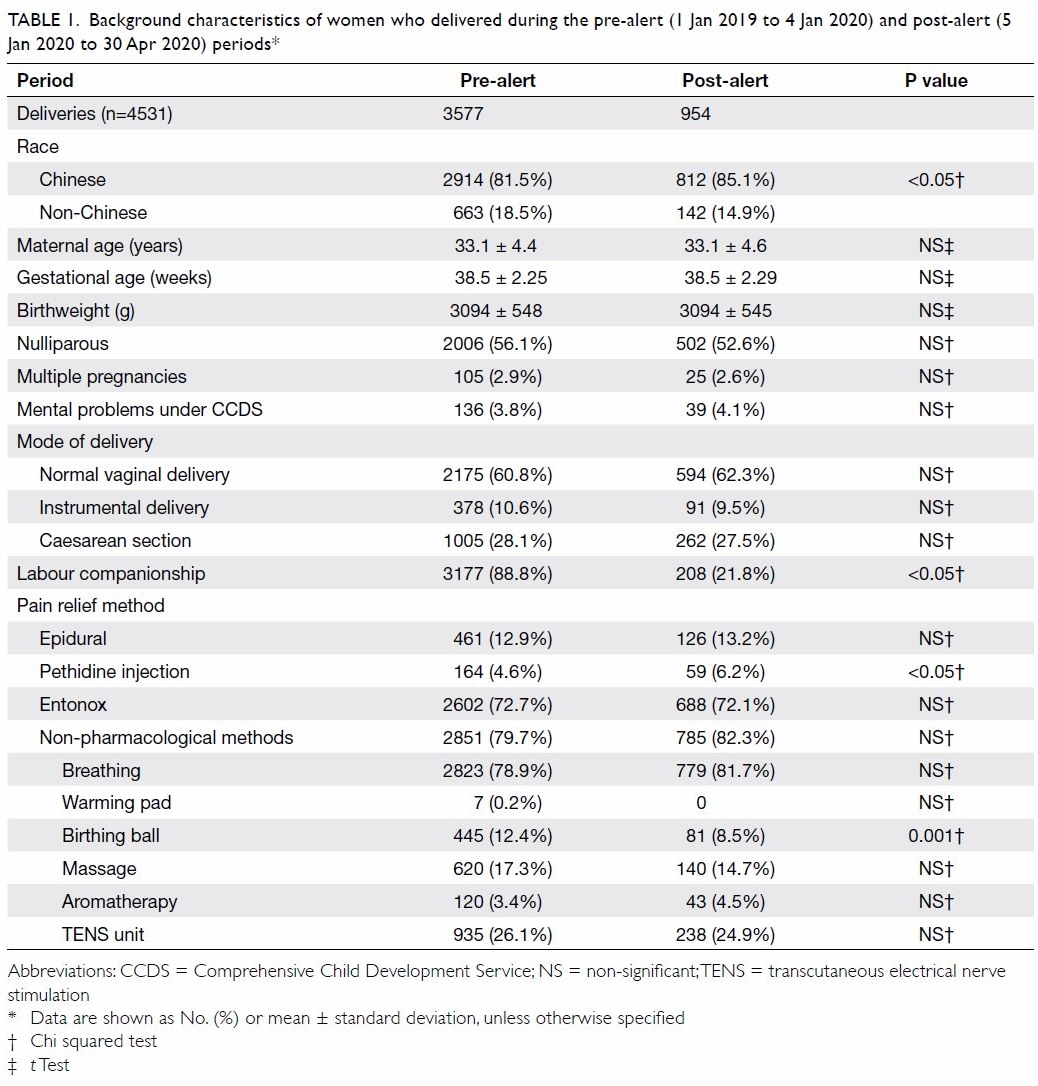

A significantly higher proportion of Chinese

women (85.1% vs 81.5%; P<0.05) delivered during

the post-alert period, while proportion of women

with labour companionship was significantly

reduced (21.8% vs 88.8%; P<0.05) compared with

the pre-alert period. For pain relief during labour,

more women received pethidine injections and

fewer women used a birthing ball during the post-alert

period. The other parameters were comparable

between the two groups (Table 1).

Table 1. Background characteristics of women who delivered during the pre-alert (1 Jan 2019 to 4 Jan 2020) and post-alert (5 Jan 2020 to 30 Apr 2020) periods

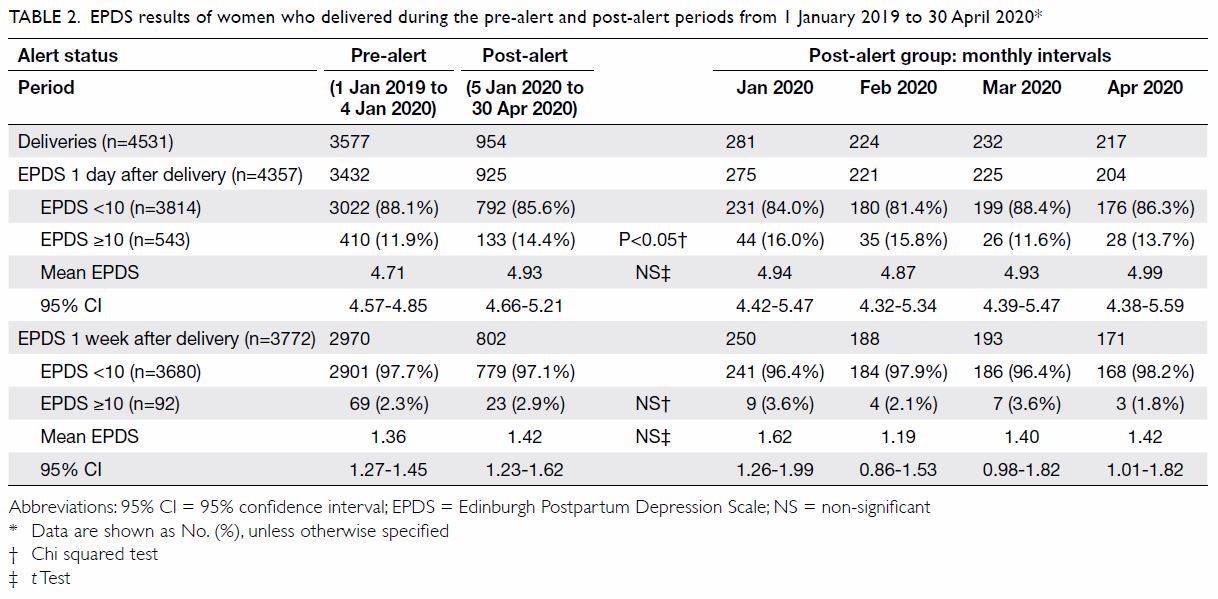

Out of 4531 total deliveries, EPDS scores

were available for 4357 (96.2%) 1 day after delivery

and 3772 (83.2%) within 1 week after delivery. A

significantly higher proportion of women had EPDS

scores of ≥10 1 day after delivery in the post-alert

group compared with the pre-alert group (14.4% vs

11.9%; P<0.05). This proportion was reduced to 2.9%

on the second assessment within 1 week of delivery, at which point the scores became comparable with those of the pre-alert group (2.3%).

Compared with the first assessment 1 day

after delivery, women in both groups demonstrated

significantly lower mean EPDS scores on the

second assessment within 1 week (pre-alert group:

4.71 vs 1.36; post-alert group: 4.93 vs 1.42; P<0.01).

The mean EPDS scores obtained on both 1 day

(4.93 vs 4.71) and within 1 week (1.42 vs 1.36) after

delivery were higher following the declaration of alert

response, although the difference was statistically

insignificant. The monthly mean EPDS score 1 day

after delivery was higher during the post-alert period

(range, 4.87-4.99) than during the pre-alert period

(4.71; 95% confidence interval=4.57-4.85; Table 2).

Table 2. EPDS results of women who delivered during the pre-alert and post-alert periods from 1 January 2019 to 30 April 2020

Discussion

The present study is the first to report the impact

of COVID-19 on obstetric care and postpartum

depression in Hong Kong. The delivery rate in public

hospitals has dropped dramatically in the post-alert

period. This drop has been more profound since

February 2020, especially among non-Chinese

women. As of 30 April 2020, there had been three

confirmed COVID-19 cases in pregnant women in

Hong Kong. Although local changes in public health

behaviour, social distancing, and isolation have

largely contained the local outbreak of COVID-19,2

these policies could disrupt couples’ delivery plans.

The reduced delivery rate could represent a shift of

childbirth from public hospitals to private ones that did not manage suspected or confirmed COVID-19

patients. Non-Chinese women might have returned

to their home countries out of fear of COVID-19.

Women who deliver in public hospitals now

increasingly have to face the challenge of childbirth

without the companionship of family members and

complete their hospital stay without visitors. All of

these could account for the reduced delivery rate in

the public sector.

Another important finding was the increased

proportion of women with high EPDS scores in

the post-alert period. We observed an increase

in EPDS scores shortly after delivery during the

post-alert period. This aligns with the findings of a

multicentre study conducted in China following the

announcement of human-to-human transmission.6

The COVID-19 pandemic could cause health

anxiety and postpartum depression.7 11 Women of

reproductive age in Hong Kong experienced

the severe adult respiratory syndrome

epidemic in 2002 to 2003. Thus, these women are potentially more

stressed than those in other countries. An emergency

response was raised in Hong Kong even before the

declaration of a pandemic by the World Health

Organization. The practice of mask wearing has been

widely adopted previously, and supplies have been

in huge demand in the past.1 The memories

of severe acute respiratory syndrome coupled with

the abrupt changes in social behaviour during the

post-alert period might have triggered more stress

in pregnant women and been reflected in their EPDS

scores. Moreover, those who remained in the public

system might not have had alternative delivery

options elsewhere. Pregnant women are vulnerable to postpartum depression, and early identification

and effective intervention from Comprehensive

Child Development Service might help to relieve

these women’s stress. These adverse effects could also

potentially be ameliorated by the provision of online

education materials, a lactation support hotline,

early postnatal discharge, and family support.

Childbirth is a major life event for a family.

Companions can provide information about

childbirth, bridge communication gaps between

healthcare workers and women, and facilitate

non-pharmacological pain relief. They can also

provide practical support, including encouraging

women in labour to move around, providing

massages, and holding their hands.12 The overall

usage of non-pharmacological pain relief was similar

between the pre- and post-alert periods. However,

a significantly lower proportion of women used

a birthing ball for pain relief during labour in the

post-alert period, probably secondary to the

suspension of childbirth companionship. Fewer

women received childbirth massages, as they are

usually provided by companions. Contrary to

this, more women needed pethidine injections

during labour. This indicates the contributory role

of childbirth companionship to women’s overall

birthing experience.

The present study illustrates the impact of

COVID-19 on pregnant women’s delivery plans and

the need for attention to their emotional disturbance.

This is important information for obstetricians

to consider during the revision and adjustment

of service provision. Remedial measures like

teleconferencing and early postnatal discharge can

facilitate speedy recovery from distress. Although we noted increased levels of postnatal depression

in the post-alert period, this study was not designed

to study the contributory effects of COVID-19,

cessation of childbirth companionship, or

elimination of visiting hours to postnatal depression.

Another limitation is the lack of data on anxiety

levels, which could provide a more comprehensive

picture of the pregnant women’s emotional health.

Moreover, this review is limited to the assessment

of women who ultimately delivered in our hospital.

Such women might be more adaptive and prepared

for the altered environment than those who chose

to give birth in the private sector or abroad. As

the study was restricted to one public hospital, the

findings might not be generalisable to hospitals in

other catchment areas, which may have different

population characteristics. The policies of restricted

gathering and social distancing might affect the

arrangements of family celebrations, baby showers,

and the cultural practice of ‘doing the month’. It will

be of interest to examine whether women’s stress

and anxiety levels change during the later postnatal

period. Further study is warranted to examine the

social and psychological responses of pregnant

women during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

Measures to limit the spread of COVID-19 have

resulted in fewer deliveries in our public hospital

and more symptoms of postpartum depression.

Obstetricians should be aware of these effects on

the psychosocial well-being of pregnant women and

offer timely intervention to provide stress relief.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: PW Hui, G Ma, MTY Seto.

Analysis or interpretation of data: PW Hui.

Drafting of the manuscript: PW Hui.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: PW Hui, G Ma, MTY Seto.

Analysis or interpretation of data: PW Hui.

Drafting of the manuscript: PW Hui.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank all midwives and nurses for their contributions to the assessment of postnatal depression in

women who delivered at Queen Mary Hospital.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding

agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This research has been approved by the Institutional Review

Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority

West Cluster (HKU/HA HKW IRB; Ref UW 20-419).

References

1. Leung GM, Cowling BJ, Wu JT. From a sprint to a marathon in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med 2020;382:e45. Crossref

2. To KK, Yuen KY. Responding to COVID-19 in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2020;26:164-6. Crossref

3. Moghanibashi-Mansourieh A. Assessing the anxiety level of Iranian general population during COVID-19 outbreak.

Asian J Psychiatr 2020;51:102076. Crossref

4. Ozamiz-Etxebarria N, Dosil-Santamaria M, Picaza-

Gorrochategui M, Idoiaga-Mondragon N. Stress, anxiety,

and depression levels in the initial stage of the COVID-19

outbreak in a population sample in the Northern Spain [in

English, Spanish]. Cad Saude Publica 2020;36:e00054020. Crossref

5. Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate psychological

responses and associated factors during the initial stage

of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic

among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res

Public Health 2020;17:1729. Crossref

6. Wu Y, Zhang C, Liu H, et al. Perinatal depressive and

anxiety symptoms of pregnant women along with COVID-19 outbreak in China. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020;223:240.

e1-9. Crossref

7. Corbett GA, Milne SJ, Hehir MP, Lindow SW, O’Connell MP.

Health anxiety and behavioural changes of pregnant

women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J Obstet

Gynecol Reprod Biol 2020;249:96-7. Crossref

8. Leung WC, Kung F, Lam J, Leung TW, Ho PC. Domestic

violence and postnatal depression in a Chinese community.

Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2002;79:159-66. Crossref

9. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal

depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh

Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 1987;150:782-6. Crossref

10. Lee DT, Yip SK, Chiu HF, et al. Detecting postnatal

depression in Chinese women. Validation of the Chinese

version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J

Psychiatry 1998;172:433-7. Crossref

11. Rashidi Fakari F, Simbar M. Coronavirus pandemic and

worries during pregnancy; a letter to editor. Arch Acad

Emerg Med 2020;8:e21.

12. Bohren MA, Berger BO, Munthe-Kaas H, Tunçalp Ö.

Perceptions and experiences of labour companionship:

a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev 2019;(3):CD012449. Crossref