Hong Kong Med J 2021 Dec;27(6):413–20 | Epub 17 Dec 2021

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Intermediate- to long-term outcomes of transvaginal mesh for treatment of Asian women with pelvic organ prolapse

Symphorosa SC Chan, MD, FRCOG; Osanna YK Wan, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology), FHKCOG; KW Choy, MSc (Med), PhD; Rachel YK Cheung, FRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Symphorosa SC Chan (symphorosa@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Short-term follow-up analyses

suggest that transvaginal mesh has limited

application for pelvic organ prolapse (POP)

treatment. This study evaluated the intermediate- and

long-term outcomes of transvaginal mesh

surgery.

Methods: This retrospective study included all

women who underwent transvaginal mesh surgery

in one urogynaecology centre. Inclusion criteria

were women with stage III/IV POP, age ≥65 years,

and (preferably) sexual inactivity. Concomitant

sacrospinous fixation and mid-urethral slings were

offered for stage III/IV apical POP and urodynamic

stress incontinence, respectively. Women were

followed up for 5 years. Subjective recurrence was

defined as reported prolapse symptoms. Objective

recurrence was defined as stage II prolapse or above.

Mesh complications and patient satisfaction were

reviewed.

Results: Of 183 women who underwent transvaginal

mesh surgery, 156 had ≥1 year of follow-up (mean,

50 ± 22 months). Subjective and objective recurrence

rates were 5.1% and 10.9%, respectively. The mesh

erosion rate was 9.6%; all affected women received

local oestrogen treatment or bedside surgical

excision. Three women received transobturator tension-free transvaginal tape for de novo (n=1)

or preoperative urodynamic stress incontinence

who did not undergo concomitant surgery (n=2);

14% of the women had de novo urgency urinary

incontinence. No women reported chronic pain.

Overall, 98% were ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with

the operation.

Conclusion: During 50 months of follow-up,

transvaginal mesh surgery for stage III/IV POP

had low subjective and objective recurrence rates.

The total re-operation rate was 9.6%. Most women

were satisfied with the operation. Based on the risk-benefit

profile, transvaginal mesh surgery may be

suitable for women who have advanced POP.

New knowledge added by this study

- In women with stage III or IV pelvic organ prolapse, transvaginal mesh surgery (with concomitant sacrospinous fixation for stage III or IV apical compartment prolapse) had low subjective (5.1%) and objective (10.9%) rates of recurrence, along with a high satisfaction rate (98%), during approximately 50 months of follow-up.

- In sexually inactive women, the transvaginal mesh erosion rate is low.

- Although some women required re-operations because of factors such as pelvic organ prolapse recurrence, stress urinary incontinence, and mesh erosion, the overall re-operation rate was 9.6%.

- In contrast to previous recommendations, transvaginal mesh surgery may be suitable for women who are sexually inactive, particularly women who have a higher risk of prolapse recurrence related to conditions such as advanced pelvic organ prolapse and levator ani muscle avulsion.

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) leads to considerable

symptomatic distress and reduced quality of life

among women.1 2 Large-scale studies of women in the

United States and Europe have shown that the risks

of undergoing POP or stress urinary incontinence

(SUI) surgery by 80 years of age range from 12.6% to 18.7%.3 4 5 Advanced POP stage and worse quality

of life are factors that increase the likelihood of

surgical treatment.2 Symptom resolution is the

most important goal among women who seek

consultations for POP.6 Importantly, quality of life

improves in women who undergo surgical treatment.7

However, there is a high mean recurrence rate after POP surgery: 36% after a follow-up interval of 0.1

to 10 years. Reoperation is also common (29.2%)

and the between-procedure interval decreases with

successive repairs.3 8

A systematic review and meta-analysis of

25 randomised controlled trials revealed that,

compared with native tissue repair, transvaginal

mesh surgery for anterior compartment prolapse

has reduced risks of awareness of prolapse (risk

ratio=0.66, 95% confidence interval=0.54-0.81),

recurrent prolapse (risk ratio=0.4, 95% confidence

interval=0.3-0.53), and repeat surgery for prolapse

(risk ratio=0.53, 95% confidence interval=0.31-0.88)

over 1 to 3 years of follow-up.9 However, transvaginal

mesh surgery carried an increased risk of repeat

surgery for a composite outcome of prolapse, SUI,

and mesh erosion (risk ratio=2.4, 95% confidence

interval=1.51-3.81). Considering this risk-benefit

profile, the authors concluded that transvaginal mesh

has limited utility in primary surgery; however, the

quality of analysed evidence only ranged from very

low to moderate. Among the randomised controlled

trials considered in that systematic review, only one

was conducted in Asia. Moreover, high objective

and subjective cure rates of transvaginal mesh and a

low mesh erosion rate have been reported over 5 to

7 years of follow-up, although some studies have had

a high rate of loss to follow-up.10 11 12

The present study was performed to evaluate

the long-term outcome of transvaginal mesh surgery

for advanced anterior compartment prolapse in a

tertiary centre. It also investigated the recurrence

rate and the types of postoperative complications

among women who underwent transvaginal mesh

surgery.

Methods

Patients

This was a retrospective analysis of prospectively

collected data concerning transvaginal mesh

reconstructive surgeries performed for POP

treatment from January 2008 to June 2019 in a

urogynaecology training centre. Ethics approval was

obtained (CREC 2015.125); the ethics committee

waived the requirement for informed consent. All

women who underwent transvaginal mesh surgery

in the study centre were recruited. Demographic

data, including age, parity, mode of delivery,

urinary symptoms (eg, SUI and/or urgency urinary

incontinence [UUI]), and symptoms of prolapse were

collected during the first consultation; the Pelvic

Organ Prolapse Quantification assessment was also

performed.13 Management options of vaginal ring

pessary and surgery were offered. For women who

chose surgery, a urodynamic study was arranged.

Transvaginal mesh surgery (ie, anterior

vaginal mesh or total vaginal mesh) was available

to women with stage III or IV anterior and apical

and posterior compartment prolapse, age ≥65 years,

and (preferably) sexual inactivity, or with recurrent

POP. Beginning in January 2013, vaginal mesh

insertion in the posterior compartment was

not performed because of published evidence

indicating no improvement from posterior vaginal

mesh, compared with native tissue repair alone.14

Transvaginal mesh was performed with concomitant

vaginal hysterectomy or a uterine-preserving

operation depending on each woman’s choice and

medical condition. In women with stage III or IV

apical compartment prolapse, concomitant bilateral

sacrospinous fixation was performed. Because

of variations in commercial product availability,

Prolift®, Perigee®, and Restorelle® were used from

2008 to 2012, 2013 to August 2017, and September

2017 to June 2019, respectively.

Surgical procedure

Women were admitted on the day of the operation.

One dose of prophylactic intravenous antibiotics

was administered on induction. The operation

was performed under either spinal or general

anaesthesia depending on each woman’s choice and

the attending anaesthetist’s assessment. For women

who chose hysterectomy, the operation began with

vaginal hysterectomy, followed by hydrodissection with adrenaline solution and midline incision over

the anterior vaginal wall. Subsequent dissection

of the bladder from the anterior vaginal wall

was performed; the sacrospinous ligament was

reached without opening the posterior vaginal wall.

Sacrospinous ligament fixation was conducted using

a Mayo-hook from 2008 to 2017; it was conducted

using a Capio device® from 2018 to 2019. Depending

on the mesh design, anterior mesh was introduced

and all arms either passed through the obturator

membranes (Prolift® and Perigee®) or were fixed to

the ipsilateral pelvic wall and sacrospinous ligament

using stitches (Restorelle®). Anterior mesh was then

attached to the bladder fascia and anterior vaginal

wall using absorbable stitches. If total vaginal

mesh was performed, the posterior vaginal wall

was opened at the midline and the sacrospinous

ligament was identified; the arms of posterior mesh

were introduced to the sacrospinous ligaments.

Cystoscopy was performed to exclude bladder injury

and confirm ureteric jets. Per rectal examination

was performed to exclude rectal perforation. Only

the edge of the vaginal epithelium was trimmed; the

anterior vaginal wall was closed by three interrupted

stitches at the distal region, followed by continuous

sutures. In the event of symptomatic posterior

compartment prolapse, posterior colporrhaphy was

performed. Concomitant continence surgery (ie,

mid-urethral sling) was performed for women with

urodynamic stress incontinence (USI). At the end

of the operation, one piece of vaginal gauze soaked

with chlorhexidine solution was packed into the

vagina and a transurethral Foley catheter was placed.

Most vaginal hysterectomies were performed by

gynaecology trainees; all procedures involving

mesh were performed by urogynaecologists or

urogynaecology subspecialty trainees under direct

supervision by urogynaecologists. Operative details

including anaesthesia type, operative time, blood

loss, and any organ injuries were collected from

electronic operative notes that were completed by

surgeons immediately after the operation.

Postoperative care and follow-up

Oral intake was resumed on the day of the operation.

Standard oral paracetamol were administered. One

course of antibiotics was administered to women

with a high risk of infection (eg, patients with diabetes

mellitus and/or a prolonged operation) and women

with postoperative fever that persisted for more than

24 hours. The vaginal gauze and Foley catheter were

removed on the day after the operation. Women

were discharged from day 1 onwards if they resumed

a normal diet, voided well, and remained afebrile.

Women were followed up once at 2 to

4 months, then annually until 5 years after surgery.

Subsequently, if they had no active pelvic floor

symptoms, they were discharged from the clinic. Earlier follow-up was offered on request.

During follow-up examinations, the attending

gynaecologist specifically asked women about

symptoms of prolapse, SUI, UUI, vaginal bleeding,

pain, and dyspareunia, as well as the severity of such

symptoms. Vaginal examinations were performed

to assess any recurrence of prolapse or mesh

erosion, in accordance with recommendations of

the International Urogynecological Association and

International Continence Society.15 16 Satisfaction

(ie, very unsatisfied, unsatisfied, satisfied, or very

satisfied) was recorded during each postoperative

visit. Subjective recurrence was defined as reported

symptoms of prolapse, vaginal bulge, or dragging

sensation. Objective recurrence was defined by the

Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification assessment

with any compartment reaching ≥1 cm above the

hymen (stage ≥II). In the event of mesh erosion,

the location, size, and area of mesh erosion were

recorded. Vaginal oestrogen cream was offered. The

options of conservative management or surgical

excision of exposed mesh were discussed with

women who experienced mesh erosion, depending

on the erosion severity, accompanying symptoms,

and their personal preferences.

If women reported symptoms of SUI or UUI, a

urodynamic study was offered. If USI was diagnosed,

tension-free vaginal tape surgery was offered

to women for whom pelvic floor exercises were

ineffective. Medical treatment was offered to women

with overactive bladder or detrusor overactivity.

Statistical analysis

SPSS software (Windows version 21.0; IBM Corp,

Armonk [NY], United States) was used to analyse

the collected data. Categorical data are shown

using descriptive statistics. Normally distributed

data are shown as means (standard deviations),

whereas non-normally distributed data are shown

as medians (ranges). The times to subjective and

objective recurrences were depicted using Kaplan–Meier curves. A P value of <0.05 was considered

statistically significant.

Results

Demographic characteristics, operative

data, and postoperative outcomes among all patients

In total, 183 women (mean age, 71.8 ± 8.4 years)

underwent transvaginal mesh surgery. Nearly all

were Hong Kong Chinese women, with the exception

of two who were non-Chinese Asian women. The

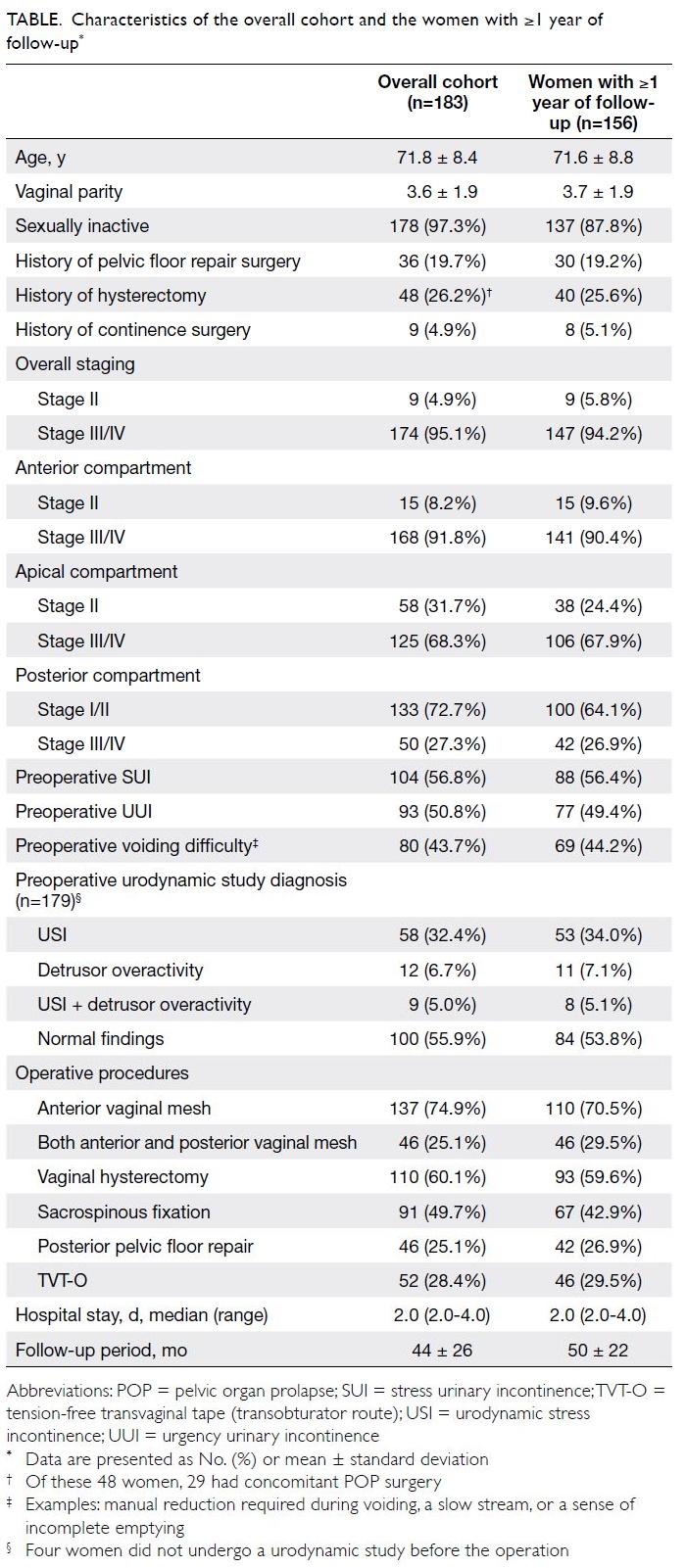

characteristics of the overall cohort are shown in the Table.

The operative procedures and hospital stay are

summarised in the Table. Forty-six (25.1%) women

had spinal anaesthesia. The mean operative time was 122.9 ± 40.7 minutes and the mean blood loss

was 193 ± 155 mL. Three (1.6%) women required

blood transfusion. One woman had bladder injury

during the trocar insertion of the anterior vaginal

mesh; the involved trocar was immediately removed

and reinserted in the correct surgical plane.

Cystoscopy showed a small perforation site at the

lateral bladder wall, but no repair was required. The

woman recovered uneventfully. One woman had a

mesh infection with abscess formation in the vulva,

requiring removal of the anterior mesh on day 18.

The infection subsided with antibiotics and drainage,

but the woman died 7 weeks after surgery because

of other medical morbidities.17

Overall, one woman was lost to follow-up

and three women, including the woman mentioned

above, died of medical diseases within 1 year; thus,

179 (97.8%) women were eligible for the postoperative

outcome analysis. Of these 179 women, 23 (12.8%)

underwent operation within 1 year prior to this

report, while 156 (87%), 113 (63%), and 77 (43%) had

completed 1, 3, and 5 years of follow-up, respectively.

The mean duration of follow-up was 50 ± 22 months.

There were no differences in demographics,

preoperative symptoms, stage and compartment of

prolapse, or operative data between the 23 women

with <1 year of follow-up and the 156 women with

≥1 year of follow-up, except for the vaginal mesh

brand (because of variations in commercial product

availability) and the duration of follow-up (Table).

Postoperative outcomes among women with

≥1 year of follow-up

Among the 156 women with ≥1 year of follow-up,

eight reported symptoms of prolapse recurrence

(subjective recurrence rate of 5.1%). Five women

had stage II POP, while three women had stage III

POP. Four women experienced recurrence in the

first year of follow-up; two, one, and one additional

women experienced recurrence in the second,

third, and fourth year of follow-up, respectively.

While five women with recurrence had conservative

treatment for POP, one woman had vaginal pessary

and two (1.3%) women had surgery to manage

prolapse recurrence. In addition, nine other women

had asymptomatic stage II POP: two had anterior

compartment prolapse and seven had posterior

compartment prolapse. The objective recurrence rate

was 10.9% (n=17). The mesh erosion rate was 9.6%

(n=15). In all, 40% of the erosions (n=6) occurred at

the posterior wall; the remaining erosions occurred

at other sites in the vagina (four anterior wall, four

vaginal vault, and one lateral wall). Most instances of

mesh erosion (n=8, 53.3%) occurred in the first year.

Ten of the 15 affected women underwent surgical

excision under local anaesthesia at the bedside;

seven, one, and two women required one, two, and

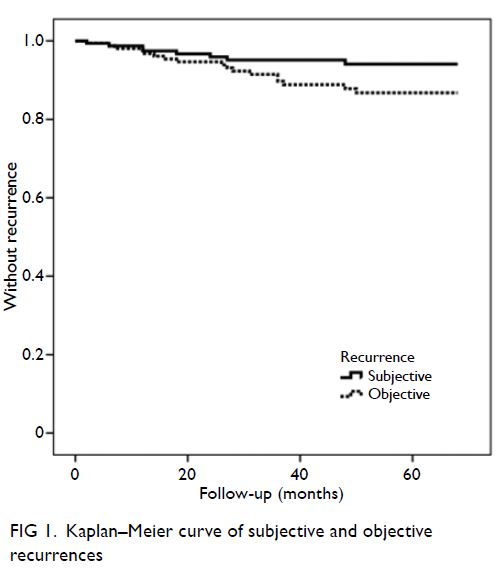

three surgical excisions, respectively. The times to subjective and objective recurrences are depicted

using Kaplan–Meier curves (Fig 1).

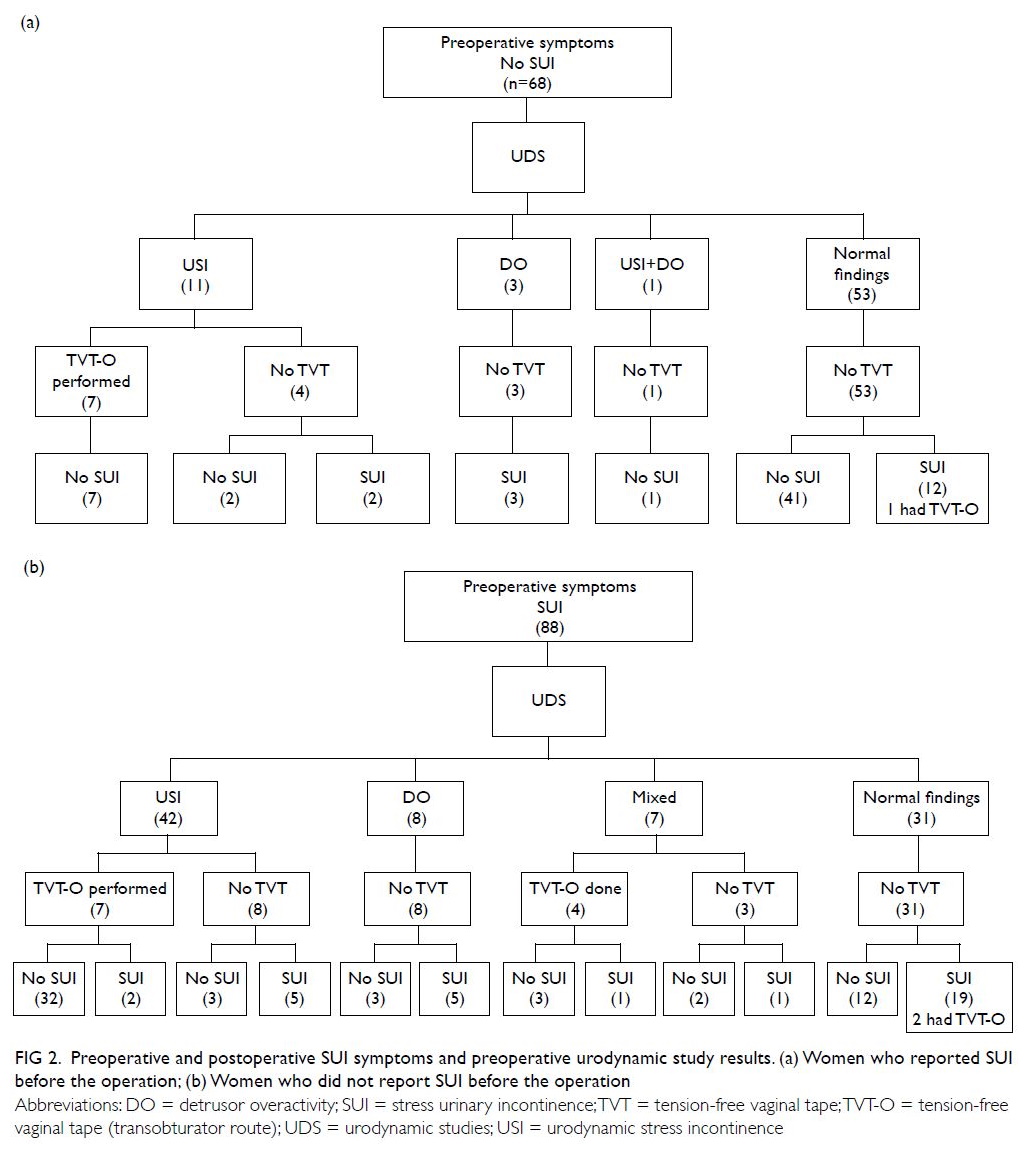

The preoperative and postoperative

symptoms of SUI are listed in Figure 2. Occult

USI was observed in 11 (16.2%) of 68 women who

reported no SUI before the operation. Among four

women who had occult USI and did not undergo

continence surgery, two had postoperative SUI;

they did not require surgical treatment. De novo

SUI occurred in 12 (7.7%) women. Only one (1/53,

1.9%) woman received tension-free transvaginal

tape (transobturator route) [TVT-O] for treatment

of SUI; the remaining 11 women had mild symptoms

or achieved improvement with pelvic floor exercise.

Among the 31 women who had preoperative SUI

but normal urodynamic study findings and did not

undergo continence surgery, 19 (61.2%) women

had postoperative SUI. Among them, two received

TVT-O afterwards. Overall, 22 (14%) women had de

novo UUI: seven received anticholinergics and the

remaining 15 had conservative treatment. No women

reported vaginal pain, pelvic pain, or dyspareunia.

Figure 2. Preoperative and postoperative SUI symptoms and preoperative urodynamic study results. (a) Women who reported SUI before the operation; (b) Women who did not report SUI before the operation

In summary, the total re-operation rate was

9.6%: two women for recurrent POP, 10 women for

mesh erosion, three women for TVT-O, and one

woman for de novo SUI. In all, 103 (66%) women

and 50 (32.1%) women were ‘satisfied’ and ‘very

satisfied’, respectively, with the operation at their

latest follow-up examination. Three women who

ever had recurrence did not report being ‘satisfied’

or ‘very satisfied’.

Discussion

This study provided a comprehensive evaluation

of the intermediate- to long-term (ie, 3 to 5 years)

outcomes of transvaginal mesh surgery in women

with advanced POP. Risk factors for POP recurrence

reportedly include levator ani muscle avulsion

(odds ratio=2.8), preoperative stage III-IV POP

(odds ratio=2.1), family history (odds ratio=1.8),

and large hiatal area (odds ratio=1.06 per 1 cm2).8

The prevalence of levator ani muscle avulsion is

higher in women with more advanced POP: we

previously reported that 54.5% and 66.7% of women

with stage III and IV POP had levator ani muscle

avulsion, respectively.18 Although this factor was

not evaluated in the present study, we presume

that a similar proportion of our cohort would have

this condition, placing them at high risk of POP

recurrence. Indeed, transvaginal mesh repair leads

to a lower rate of anterior compartment prolapse

recurrence, compared with native tissue repair in

women with levator ani muscle avulsion.19 20

Transvaginal mesh was not recommended

in a systematic review and meta-analysis of 25

randomised controlled trials, based on its risk-benefit

profile. The risk of awareness of prolapse

was 13%; the risks of repeat surgery for prolapse and SUI were 1.8% and 2.9%, respectively.9 However, if

the transvaginal mesh treatment efficacy remains

high over a longer follow-up period and the risk of

morbidity is low, the above recommendation may not

apply to all women. In our cohort, these risks were

5.1%, 1.3%, and 1.9% for a mean follow-up period of

50 months. This indicates a tendency towards lower

POP recurrence risks in our cohort. The objective

recurrence rate of 10.6% also tended to be lower,

compared with previous studies that recruited

women who had stage II POP8, although 95% of our

women had stage III or IV POP. Our subjective and

objective recurrence rates are similar to the rates in

other Asian centres in the past decade.10 11

Apical compartment prolapse is more

prevalent among women in Hong Kong, compared

with Caucasian women.18 21 Furthermore, apical

support is important in the management of

anterior compartment prolapse, which comprises

impairment of the pubovisceral muscle and the

uterosacral and cardinal ligaments.10 22 23 Thus, we

performed concomitant sacrospinous fixation to

suspend the vaginal vault among women in this

study; this additional procedure did not increase

perioperative morbidity. This may explain why the

vaginal vault was not commonly involved in women

who had subjective or objective recurrence of POP

in the present study. Most women with objective

recurrence had stage II posterior compartment

prolapse, but they were asymptomatic.

The mesh erosion rate was 9.6%; 40% of

erosions were caused by posterior vaginal mesh.

The erosion rate for anterior vaginal mesh alone was 5.8%; this was comparable with previously

reported rates of 2.7% to 20%, with a mean of

11.1%.10 11 24 25 26 Furthermore, our rate was similar to

other Asian centres where a low mesh erosion rate

was reported.10 11 Most instances of erosion in our

study occurred within the first or second year of

follow-up; approximately two-thirds of the affected

women underwent excision of the exposed part

of the mesh and repair of the vaginal epithelium

under local anaesthesia at the bedside.17 Among

the various types of possible mesh complications,

Warembourg et al24 reported that mesh erosion was the most common complication that required

re-operation; however, it was also treated most

effectively. However, more serious complications

could occur, such as erosion into the urinary tract or

bowel.24 No instances of vaginal pain or dyspareunia

were reported in our cohort, in contrast to previous

findings26; this was presumably because we mainly

offered transvaginal mesh surgery to women who

were sexually inactive. The proportion of women

with POP who report sexual inactivity is generally

high (64%) in Hong Kong.27 Further research is

needed to determine whether ethnicity contributes to vaginal pain or dyspareunia after transvaginal mesh surgery.

Preoperative urodynamic studies showed that,

of 68 women who did not report SUI, 16% and 6% had

occult USI and other diagnoses, respectively; thus,

only 53 (78%) women had no abnormal findings. De

novo SUI occurred in 12 of these 53 women (7.7%

of all 156 women with ≥1 year of follow-up); only

one woman requested continence surgery. Although

some women reported symptoms of SUI, our

policy was not to offer continence surgery if no USI

was evident during the urodynamic study. Of the

remaining 31 of 53 women with no abnormal findings,

only two subsequently required continence surgery.

Overall, repeat surgery for SUI only occurred in

three (1.9%) women; we regarded this as a low risk of

repeat surgery. Preoperative urodynamic studies and

our more conservative approach (ie, not frequently

offering continence surgery) might have reduced the

risk of long-term complications. However, treatment

was offered to women with preoperative clinically

bothersome USI. Women who received concomitant

TVT-O were satisfied with this management.

This study had some limitations. First, this

was a single-centre study with a moderate sample

size. However, the data were collected prospectively

using a standardised form. Second, a health-related

quality of life questionnaire was not used because

validated questionnaires were unavailable when

transvaginal mesh surgery first began in our centre;

thus, no data were available for some women.1 We

plan to investigate these data in a future study.

Finally, the effects of sexual function on the surgical

outcomes were not explored because most women

in this cohort were sexually inactive. We did not

recommend transvaginal mesh surgery to women

who were sexually active because there were

increased risks of mesh erosion and dyspareunia.

Conclusion

Women with stage III or IV POP experienced a

benefit from transvaginal anterior mesh surgery (and

concomitant sacrospinous fixation if concomitant

stage III/IV apical compartment prolapse) with

low risks of subjective recurrence of POP (5.1%),

objective recurrence of POP (10.9%), and re-operation

for POP recurrence (1.3%) at a mean

follow-up interval of 50 months. Although some

women required re-operations because of various

factors (eg, POP recurrence, SUI, and mesh erosion),

the overall re-operation rate was 9.6%. Most

women were satisfied or highly satisfied with the

transvaginal mesh surgery. This type of surgery may

be suitable for women with POP who are sexually

inactive, particularly women who have a higher risk

of recurrence related to conditions such as advanced

POP and levator ani muscle avulsion.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: SSC Chan, OYK Wan, RYK Chung.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: SSC Chan.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: SSC Chan, OYK Wan, RYK Chung.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: SSC Chan.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Miss Loreta Lee for data

collection and data entry for this research.

Declaration

Portions of the results were presented in the 26th Asia and Oceania Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology (AOFOG)

Congress in the Philippines in 2019, during a talk that received

the “Best Oral Presentation” award in the Urogynaecology

session.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from The Joint Chinese

University of Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster

Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Ref: CREC 2015.125).

The requirement for written informed consent was waived by

the ethics board.

References

1. Chan SS, Cheung RY, Yiu AK, et al. Chinese validation of pelvic floor distress inventory and pelvic floor impact

questionnaire. Int Urogynecol J 2011;22:1305-12. Crossref

2. Chan SS, Cheung RY, Yiu KW, Lee LL, Pang AW, Chung TK.

Symptoms, quality of life, and factors affecting women’s

treatment decisions regarding pelvic organ prolapse. Int

Urogynecol J 2012;23:1027-33. Crossref

3. Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse

and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 1997;89:501-6. Crossref

4. Wu JM, Matthews CA, Conover MM, Pate V, Funk MJ. Lifetime risk of stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ

prolapse surgery. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:1201-6. Crossref

5. Løwenstein E, Ottesen B, Gimbel H. Incidence and lifetime risk of pelvic organ prolapse surgery in Denmark from

1977 to 2009. Int Urogynecol J 2015;26:49-55. Crossref

6. Lowenstein L, FitzGerald MP, Kenton K, et al. Patient-selected goals: the fourth dimension in assessment of pelvic

floor disorders. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct

2008;19:81-4. Crossref

7. Chan SS, Cheung RY, Lai BP, Lee LL, Choy KW, Chung TK. Responsiveness of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire in women undergoing

treatment for pelvic floor disorders. Int Urogynecol J

2013;24:213-21. Crossref

8. Friedman T, Eslick GD, Dietz HP. Risk factors for prolapse recurrence: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int

Urogynecol J 2018;29:13-21. Crossref

9. Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Christmann-Schmid C, Haya N, Marjoribanks J. Transvaginal mesh or grafts

compared with native tissue repair for vaginal prolapse.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;(2):CD012079. Crossref

10. Lo TS, Pue LB, Tan YL, Wu PY. Long-term outcomes of synthetic transobturator nonabsorbable anterior

mesh versus anterior colporrhaphy in symptomatic,

advanced pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Int Urogynecol J

2014;25:257-64. Crossref

11. Dong S, Zhong Y, Chu L, Li H, Tong X, Wang J. Agestratified

analysis of long-term outcomes of transvaginal

mesh repair for treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Int J

Gynecol Obstet 2016;135:112-6. Crossref

12. Meyer I, McGwin G, Swain TA, Alvarez MD, Ellington DR,

Richter HE. Synthetic graft augmentation in vaginal

prolapse surgery: long-term objective and subjective

outcomes. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2016;23:614-21. Crossref

13. Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bø K, et al. The standardization

of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic

floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;175:10-7. Crossref

14. Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Schmid C. Surgical

management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev 2013;(4):CD004014. Crossref

15. Haylen BT, Freeman RM, Swift SE, et al. An International

Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International

Continence Society (ICS) joint terminology and

classification of the complications related directly to the

insertion of prostheses (meshes, implants, tapes) & grafts

in female pelvic floor surgery. Int Urogynecol J 2011;22:3-15. Crossref

16. Toozs-Hobson P, Freeman R, Barber M, et al. An

International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the

terminology for reporting outcomes of surgical procedures

for pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J 2012;23:527-35. Crossref

17. Wan OY, Chan SS, Cheung RY, Chung TK. Mesh-related complications from reconstructive surgery for pelvic organ

prolapse in Chinese patients in Hong Kong. Hong Kong

Med J 2018;24:369-77. Crossref

18. Yu CH, Chan SS, Cheung RY, Chung TK. Prevalence of

levator ani muscle avulsion and effect on quality of life

in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J

2018;29:729-33. Crossref

19. Wong V, Shek KL, Goh J, Krause H, Martin A, Dietz HP.

Cystocele recurrence after anterior colporrhaphy with

and without mesh use. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol

2014;172:131-5. Crossref

20. Rodrigo N, Wong V, Shek KL, Martin A, Dietz HP. The use

of 3-dimensional ultrasound of the pelvic floor to predict

recurrence risk after pelvic reconstructive surgery. Aust N

Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2014;54:206-11. Crossref

21. Cheung RY, Chan SS, Shek KL, Chung TK, Dietz HP.

Pelvic organ prolapse in Caucasian and Asian women:

a comparative study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol

2019;53:541-5. Crossref

22. Chen L, Ashton-Miller JA, Hsu Y, DeLancey JO. Interaction

among apical support, levator ani impairment, and anterior

vaginal wall prolapse. Obstet Gynecol 2006;108:324-32. Crossref

23. Stanford EJ, Cassidenti A, Moen MD. Traditional native

tissue versus mesh-augmented pelvic organ prolapse

repairs: providing an accurate interpretation of current

literature. Int Urogynecol J 2012;23:19-28. Crossref

24. Warembourg S, Labaki M, de Tayrac R, Costa P, Fatton B.

Reoperations for mesh-related complications after pelvic

organ prolapse repair: 8-year experience at a tertiary

referral center. Int Urogynecol J 2017;28:1139-51. Crossref

25. Deffieux X, de Tayrac R, Huel C, et al. Vaginal mesh erosion

after transvaginal repair of cystocele using Gynemesh or

Gynemesh-Soft in 138 women: a comparative study. Int

Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2007;18:73-9. Crossref

26. Hüsch T, Mager R, Ober E, Bentler R, Ulm K, Haferkamp A.

Quality of life in women of non-reproductive age with

transvaginal mesh repair for pelvic organ prolapse: a

cohort study. Int J Surg 2016;33:36-41. Crossref

27. Cheung RY, Lee JH, Lee LL, Chung TK, Chan SS. Vaginal

pessary in women with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse:

a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2016;128:73-80. Crossref