© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Pictorial Blood Loss Assessment Chart for evaluating heavy menstrual bleeding in Asian women

Jennifer KY Ko, MB, BS, FHAKM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1; Terence T Lao, MD2; Vincent YT Cheung, FRCOG, FRCSC1

1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The University of Hong Kong and Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The University of Hong Kong (Honorary), Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Jennifer KY Ko (jenko@hku.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Heavy menstrual bleeding is a

common gynaecological problem, but some

women may prefer not to articulate their menstrual

problems. The objective of this study was to evaluate

the usefulness and acceptability of the Pictorial

Blood Loss Assessment Chart (PBAC) as a self-screening

tool in evaluation of menstrual blood loss

among Asian women in Hong Kong.

Methods: This prospective cohort study recruited

206 women from the general gynaecology ward

and out-patient clinic: 118 had self-perceived heavy

menstrual bleeding and 88 had self-perceived normal

menstrual flow. Participants were asked to fill in the

PBAC for one menstrual cycle.

Results: Compared with women who had self-perceived

normal menstrual flow, women with self-perceived

heavy menstrual bleeding had significantly

higher total PBAC scores and numbers of flooding

episodes, larger clot sizes and numbers, more days

of bleeding, and lower haemoglobin levels. Receiver-operating characteristic curve analysis demonstrated good pairwise associations of self-perceived

symptoms with PBAC score and haemoglobin level.

Conclusions: The PBAC can be used to differentiate

self-perceived heavy and normal menstrual bleeding

in Asian women in Hong Kong. It can also serve as

an additional indicator of possible heavy menstrual

bleeding to alert women of the need to seek early

medical attention.

New knowledge added by this study

- The Pictorial Blood Loss Assessment Chart (PBAC) offers a semi-objective method for evaluation of heavy menstrual bleeding in women whose cultural backgrounds may cause reluctance in discussing their gynaecological or menstrual problems.

- More than 10% of women with self-perceived normal menstrual bleeding had PBAC scores >100, had anaemia, and/or required iron supplements.

- The best PBAC cut-off score (76) yielded a sensitivity of 93.2% and a specificity of 83.0% for predicting selfperceived heavy menstrual bleeding.

- The PBAC may be useful as a self-screening tool for heavy menstrual bleeding among Asian women in Hong Kong, facilitating early medical evaluation of apparently asymptomatic women with unrecognised anaemia.

- Development of PBAC-containing mobile apps or websites may improve the usability of the PBAC in clinical and research settings.

- Localisation of the PBAC to include items encountered daily (such as ‘tofu’ or ‘palm’, rather than coins) could improve the usefulness of this tool.

- The PBAC may be useful for evaluation of responses to interventions during randomised controlled trials involving women with adenomyosis and uterine fibroids.

Introduction

The clinical decision regarding a need for treatment

of menstrual bleeding relies on the patient’s

perception of flow amount and its effects on

her physical, emotional, and social well-being.1

However, retrospective recall regarding the amount

of menstrual flow in previous cycles is heavily

influenced by a woman’s subjective perception and is not always associated with the measured blood

loss.2 The ‘gold standard’ approach for assessment

of menstrual blood loss is the alkaline haematin

method, which requires a woman to collect all

soiled sanitary products for laboratory assessment2;

however, this is a cumbersome non-hygienic impractical method outside the research setting.

The Pictorial Blood Loss Assessment Chart (PBAC) is a scoring system developed as a semi-quantitative

evaluation of menstrual blood loss,

which considers the number of sanitary products

used, the degree to which these products are soiled

with blood, the number and size of blood clots

passed, and the number of flooding episodes.3 The

PBAC has been validated with the alkaline haematin

method to diagnose heavy menstrual bleeding in

several studies in other populations.3 4 5 Furthermore,

the PBAC has been used as a measurement tool to

evaluate menstrual blood loss in systematic reviews

and randomised controlled clinical trials.6

In the clinical setting, it can be difficult for a

physician to determine the amount and implication

of menstrual flow in a patient reporting heavy

menstrual bleeding. Menstruation is a taboo topic in

many communities, including among Asian women

in Hong Kong.7 8 9 10 Some women may prefer not to, or

find it difficult or embarrassing to, articulate details

regarding their menstrual problems.7 8 9 Furthermore,

some women may be unaware of heavy menstrual

bleeding.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the

usefulness of the PBAC as a self-evaluation tool for

heavy menstrual bleeding. Additionally, we sought to

determine the acceptability of the PBAC and whether

PBAC scores were associated with menstrual blood

loss severity among Asian women in Hong Kong.

Methods

This prospective cohort study compared PBAC scores

between women who presented with and without

heavy menstrual bleeding. Women were recruited

between November 2014 and January 2016 through

the gynaecology ward or the general gynaecology

out-patient clinic of a university-affiliated hospital. They attended the out-patient clinic for routine

follow-up or were admitted to the ward for elective

or emergent treatment. Inclusion criteria included

good general health, absence of other medical

conditions which might lead to anaemia, no prior

PBAC use, and age ≥18 years. Women were excluded

if they were pregnant, in menopause, receiving

hormonal treatment, mentally incompetent,

and/or undergoing treatment/monitoring of a

gynaecological malignancy. Ethics approval was

obtained from the Institutional Review Board of The

University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong

Kong West Cluster. Written informed consent was

obtained from all study participants.

Women were approached by the research

nurse and were placed into heavy menstrual bleeding

and normal menstrual bleeding groups based on

their self-reported menstrual cycle symptoms over

the preceding 6 months. All group allocations were

noted by the nurse. All participants, regardless of

perceived menstrual flow, were instructed by the

research nurse to fill in a PBAC for one cycle in the

next cycle. They were also instructed to answer a

question regarding whether they found the PBAC

acceptable (yes/no) and a question regarding the

ease of use of the PBAC (scale of 1-5; 1=easiest

and 5=hardest). The PBAC originally described by

Higham et al3 was used, but diagrams of clot sizes

were modified to the sizes of local coins. The PBAC

consisted of a series of diagrams representing lightly,

moderately, and heavily soaked towels and tampons

(depending on the degree of staining) to evaluate

menstrual blood loss.3 The numbers of pads or

tampons used each day were recorded. In the event

of clot passage, the number and size were recorded;

flooding episodes were also recorded. A total score

was calculated by multiplying by a factor of 1 for

each lightly soiled item, 5 for each medium soiled

item, 10 for a fully soaked tampon, and 20 for a

fully soaked pad.3 Small and large clots were given a

score of 1 and 5, respectively.3 Women continued to

use their own sanitary products (ie, products used

prior to the study) and were asked to document

the types and sizes of sanitary products used. Each

woman was asked to return the completed PBAC to

the research nurse by mail in a stamped envelope.

The following clinical data were retrieved from the

women’s electronic medical records and used in the

analysis: age, haemoglobin level within 3 months

before the consultation or on the day of consultation

(if available), and the iron supplement status (using/not using).

The sample size was determined based on an

anticipated 20% difference in accuracy endpoints

between study groups and a standard deviation

of 40%. Allowing for 10% non-responders, the

calculated sample size per group was 70 women.

Statistical tests were performed using SPSS Statistics (Windows version 24; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY],

United States). Comparisons between groups were

made using the Chi squared test for categorical

variables and the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U

test for continuous variables. Continuous variables

were expressed as median and range. A P value of

<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The

kappa statistic was used to test agreement between

subjective evaluation of heavy menstrual bleeding

and the PBAC score at various cut-off scores.

Predictions of heavy menstrual bleeding according

to the PBAC score and haemoglobin level were

determined using area under the receiver-operating

characteristic curve analysis.

Results

The response rate was better than expected and

more women than expected were recruited in

each clinic session; this yielded a final sample size

larger than originally planned. However, among

292 women who were asked to complete the PBAC,

the return rate was only 206/292 (70.5%). In all,

118 women had self-perceived heavy menstrual

bleeding and 88 women had self-perceived normal

menstrual flow. Haemoglobin level data were

available in 179/292 (61.3%) women (116 in the heavy

menstrual bleeding group and 63 in the normal

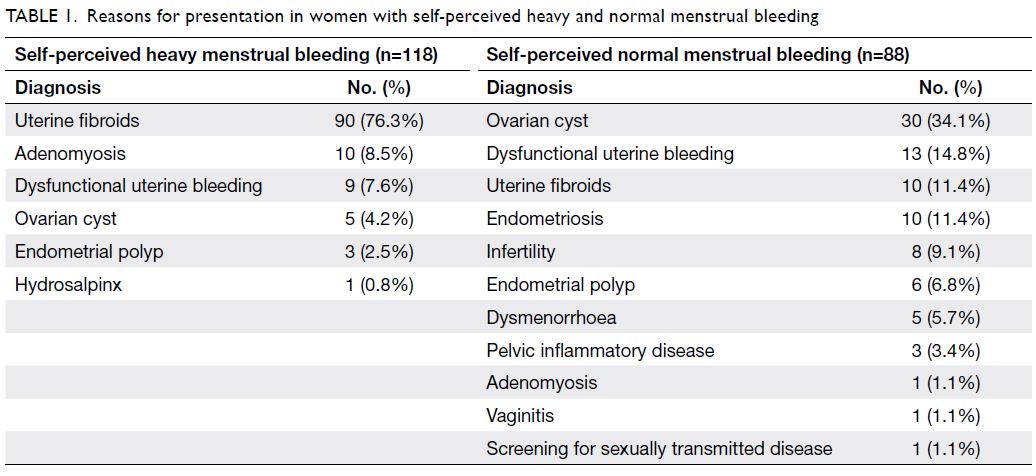

menstrual bleeding group). Table 1 summarises

the reasons for presentation in both groups of

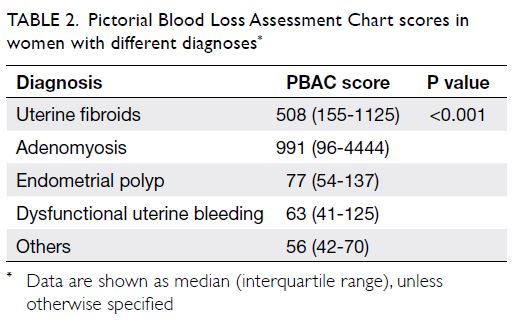

women. The PBAC scores based on different

diagnoses are shown in Table 2. Women with heavy

menstrual bleeding were older than women with

normal menstrual bleeding (median age 44 years,

[interquartile range=40-48] vs 38 years [interquartile

range=31-43], respectively, P<0.001). There was no

significant difference in education level between

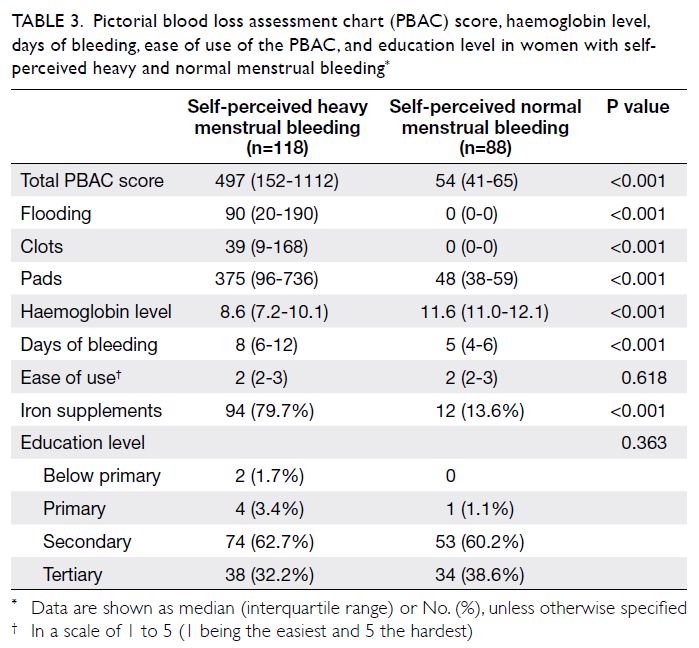

groups (Table 3).

Table 3. Pictorial blood loss assessment chart (PBAC) score, haemoglobin level, days of bleeding, ease of use of the PBAC, and education level in women with selfperceived heavy and normal menstrual bleeding

Nearly all women in the study used pads; one

woman used both pads and tampons. In total, 147/206

(71.4%) women used various brands and sizes of

pads with distinct absorbency characteristics during

the menstrual cycle; the remaining 59/206 (28.6%)

women used only one type of pad. Seven women

used diapers and three women used postpartum

pads. The median PBAC scores of women who

reported heavy and normal menstrual bleeding

were 497 (interquartile range=152-1112) and 54

(interquartile range=41-65), respectively (Table 3).

Compared with women who had normal menstrual

flow, women with heavy menstrual bleeding had

significantly higher total PBAC scores and numbers

of flooding episodes, larger clot sizes and numbers,

more days of bleeding, and lower haemoglobin levels

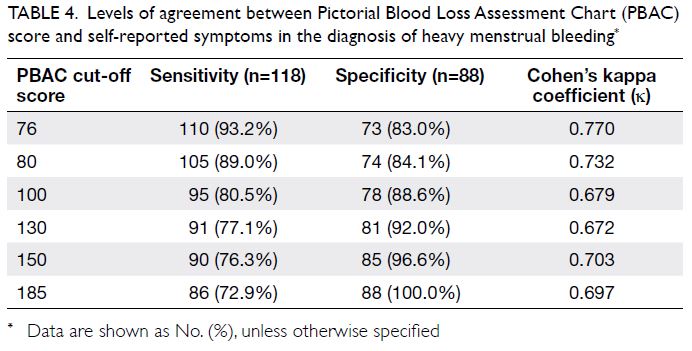

(Table 3). Using cut-off scores of 76, 80, 100, 130, 150, and 185, levels of agreement between PBAC score

and self-reported symptoms in the diagnosis of heavy

menstrual bleeding are shown in Table 4. Women with

anaemia, defined as haemoglobin level <11.0 g/dL,

had significantly higher median PBAC scores than

did women without anaemia (508 [interquartile range=168-1087] vs 58 [interquartile range=46-84],

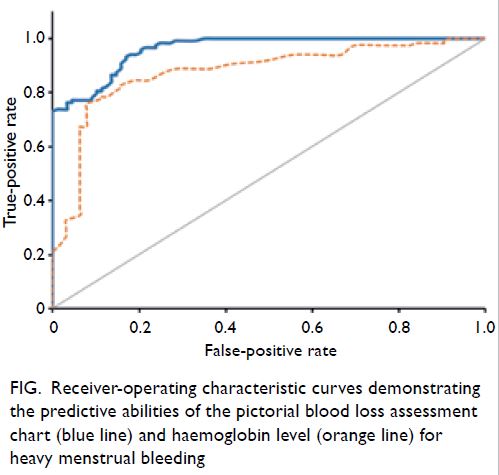

P<0.01). Receiver-operating characteristic curves

demonstrating the predictive abilities of the PBAC

and haemoglobin level for heavy menstrual bleeding

are shown in the Figure. The area under the receiver-operating

characteristic curves of the PBAC and

haemoglobin level for prediction of heavy menstrual

bleeding were 0.961 (95% confidence=0.940-09.982)

and 0.876 (95% confidence=0.821-0.931),

respectively. The PBAC cut-off score with the highest

Youden index was 76, which yielded a sensitivity of

93.2% and a specificity of 83.0% for predicting self-perceived

heavy menstrual bleeding.

Table 4. Levels of agreement between Pictorial Blood Loss Assessment Chart (PBAC) score and self-reported symptoms in the diagnosis of heavy menstrual bleeding

Figure. Receiver-operating characteristic curves demonstrating the predictive abilities of the pictorial blood loss assessment chart (blue line) and haemoglobin level (orange line) for heavy menstrual bleeding

All women in our study were able to complete

the PBAC. Missing information was filled in with the

help of the research nurse via phone contact after

return of the PBAC. Twenty-eight women (13.6%)

who began the PBAC on the day of consultation

were contacted by phone to urge them to return

the PBAC using the stamped envelopes. Another

11 women (5.4%) with prolonged menstrual

bleeding did not provide full details regarding their

menstrual bleeding; they were contacted by phone

for confirmation. In all, 200/206 women (97.1%)

found the PBAC acceptable: 113/118 (95.8%) in the

heavy menstrual bleeding group and 87/88 (98.9%)

in normal menstrual bleeding group. Assuming

that the reason for non-response was that those

women found the PBAC to be unacceptable, the

acceptability rate was 200/292 (68.5%). There was no

significant difference in the perceived ease of use of

the PBAC; the median rating was 2 in both groups

(P=0.618; Table 3). Notable written comments

from the women concerning the PBAC were that it

could not accurately describe their menstrual blood

loss (n=19), it required explanation (n=11), it was

inconvenient or involved recall problems (n=3), and

it did not record other symptoms which were more

distressing (n=1).

Discussion

Our results suggested that the reported PBAC

scores in this group of Asian women comprised a

useful tool for differentiating self-perceived heavy

and normal menstrual bleeding. Heavy menstrual

bleeding considerably impacts a woman’s quality of

life; interventions should be designed to improve

the quality of life, rather than focusing on the exact

amount of menstrual blood loss.1 Nevertheless,

some women may be unaware of heavy bleeding or

find it difficult to describe the amount of menstrual

flow. The PBAC offers a semi-objective method for

initial self-evaluation of the amount of menstrual

bleeding in women whose cultural backgrounds may

cause reluctance in discussing their gynaecological

or menstrual problems. This self-evaluation can alert

women to seek medical attention, thus facilitating

clinical evaluation and treatment. The PBAC cut-off scores included in Table 4 have been used in previous

studies to imply heavy menstrual bleeding.3 4 5 11

The recommendation of a particular cut-off score

depends on the clinical context (ie, whether a higher

sensitivity or specificity is required). For example, if

the PBAC is used as a screening tool, a lower cut-off

score may be appropriate to alert women to seek

medical attention. In contrast, if the PBAC is used to

evaluate women with heavy menstrual bleeding for

potential participation in a research study, a higher

cut-off score may be used to recruit women with

more severe symptoms to evaluate their response to

treatment.

In our study, 10 women (11.4%) in the self-perceived

normal menstrual bleeding group had

PBAC scores of >100, although they reported normal

menstrual bleeding. In the self-perceived normal

menstrual bleeding group, 14 women had anaemia

(haemoglobin level <11.0 g/dL), among which five

women had a haemoglobin level of <10.0 g/dL.

Twelve women who reported normal menstrual

bleeding were using iron supplements. Although

most women accurately recognised heavy menstrual

bleeding, use of the PBAC identified an additional

10% of women who might have unperceived

abnormal bleeding. Of the 10 women with self-perceived

normal menstrual bleeding (PBAC scores

of 101-180), seven (70%) had anaemia. Thus, use

of the PBAC might enable identification of a small

group of apparently asymptomatic women who had

unrecognised anaemia, thereby facilitating earlier

medical attention.

In our study, women were asked to use their

own sanitary products, rather than using specific

brands and sizes of pads; thus, our findings are more

representative of realistic PBAC use, compared

with results acquired in a research setting. Most

women used different brands and sizes of pads with

different absorbency characteristics, even within

a single cycle. In addition, several women used

adult diapers or postpartum pads, which implied

substantial difference in blood loss compared with

the usual sanitary pads. The range of PBAC scores

was much larger in our study than in previous

studies.3 4 5 11 12 One woman in our study had a PBAC

score of 32 301; she had prolonged vaginal bleeding

for 56 days and had a haemoglobin level of 4.5 g/dL.

Women with adenomyosis and uterine fibroids had

significantly higher PBAC scores than did women

with other diagnoses. Therefore, the PBAC may be

useful for evaluation of responses to interventions

during randomised controlled trials involving these

groups.

Although women in our study who returned

the PBAC found it acceptable and generally easy to

use, the return rate should be considered. Notably,

19/206 (9.2%) women commented that the range of

icons in the PBAC did not accurately reflect their blood loss on pads or clots because they experienced

difficulty in evaluating the amount of blood loss

(based on a particular stain) when comparing among

pads with different absorbency characteristics. The

clots were of irregular size and women felt that a

scale or use of items encountered daily (such as ‘tofu’

or ‘palm’, rather than coins) could more accurately

describe these clots. Women (particularly in the

heavy menstrual bleeding group) who had to sit on

the toilet during flooding episodes could not quantify

their bleeding; several women with prolonged

bleeding did not continue the PBAC evaluation

because they felt that continuing the documentation

was time-consuming and annoying. In total, 5.3%

of the women commented that clearer instructions

could be provided. This is consistent with the

findings by Zakherah et al,5 who reported that

improved instructions led to greater accuracy when

a physician or nurse reviewed the documentation

with the patient. The role of the nurse in our study

was crucial. Our research nurse found it helpful to

demonstrate to the women how to fill in the PBAC

using their current or previous cycle; the nurse also

helped the women to complete the PBAC in the event

of substantial missing information, especially among

women with prolonged menstrual bleeding. Some

women probably completed the PBAC by recall,

rather than in a day-by-day manner. This aspect

should be considered when the PBAC is applied as

a self-screening tool. The development of PBAC-containing

mobile apps or websites accessible by the

public may improve the usability of the PBAC as a

self-screening tool in terms of better convenience

and less recall bias, especially among younger

women.

Our study had some limitations. First, we

only evaluated use of the PBAC in a small group

of patients who presented for clinical treatment,

rather than the general population; this may limit

the generalisability of the results. Second, we did not

study the inter-cycle variability in PBAC score or the

effects of other demographic factors (eg, household

income) which may affect the use of the PBAC.

Although only one cycle of menstrual bleeding was

charted in our study and women may have unusual

menstrual flow in subsequent cycles, previous

studies have demonstrated high consistency with

low inter-cycle variation in women who completed a

second PBAC evaluation without treatment.11 Third,

patients may have been offered treatment during the

consultation; because the PBAC was completed in

the cycle after consultation, the PBAC score may not

fully reflect the pre-consultation reported symptoms,

especially among women with self-perceived heavy

menstrual bleeding. Fourth, compliance with iron

therapy was not checked; this could have affected the

haemoglobin results. However, the aim of our study

was to evaluate the relationship between the PBAC score and self-perceived menstrual flow. Overall,

the results of this population-specific study might

support the use of the PBAC as a potential self-screening

tool for heavy menstrual bleeding among

Asian women in Hong Kong.

There is considerable endpoint heterogeneity

in the current literature with respect to the

outcomes of various treatment options for heavy

menstrual bleeding. Furthermore, there is currently

no core outcome set for valid comparison and

interpretation of data from research studies and

assessments regarding abnormal uterine bleeding.6

Although PBAC scores have shown high inter-individual

variation, they had low intra-individual

variation;11 thus, the PBAC may be useful in future

studies of treatment responses in individual women.

Despite the large variety of commercially available

sanitary products, the PBAC remains a reliable

screening tool for semi-quantitative evaluation of

menstrual blood loss, which can alert women to seek

medical attention for heavy menstrual bleeding.

Additional studies are needed to confirm the clinical

usefulness of the PBAC, especially in the context of

the evolution and advancement of superabsorbent

sanitary products currently available. Overall, the

advantages of the PBAC are its relative objectivity

and flexibility as a tool for screening, diagnosis, and

evaluation of treatment effect.

Author contributions

Concept or design: JKY Ko, VYT Cheung.

Acquisition of data: JKY Ko, VYT Cheung.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: JKY Ko.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: JKY Ko, VYT Cheung.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: JKY Ko.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Ms Wai-ki Choi for patient recruitment, teaching women about the Pictorial Blood Loss Assessment

Chart, and managing the database.

Declaration

The study was presented in an oral presentation at the FOCUS in O&G 2018 Congress in Hong Kong (17-18 November 2018).

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of The University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority

Hong Kong West Cluster (Ref: UW 14-299). Written informed

consent was obtained from all study participants.

References

1. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline.

Heavy menstrual bleeding: assessment and management.

14 Mar 2018 (last updated 24 May 2021). Available from:

http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng88. Accessed 25 Nov 2021.

2. Magnay JL, O’Brien S, Gerlinger C, Seitz C. A systematic

review of methods to measure menstrual blood loss. BMC

Womens Health 2018;18:142. Crossref

3. Higham JM, O’Brien PM, Shaw RW. Assessment of

menstrual blood loss using a pictorial chart. Br J Obstet

Gynaecol 1990;97:734-9. Crossref

4. Janssen CA, Scholten PC, Heintz AP. A simple visual

assessment technique to discriminate between

menorrhagia and normal menstrual blood loss. Obstet

Gynecol 1995;85:977-82. Crossref

5. Zakherah MS, Sayed GH, El-Nashar SA, Shaaban MM.

Pictorial blood loss assessment chart in the evaluation of

heavy menstrual bleeding: diagnostic accuracy compared

to alkaline hematin. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2011;71:281-4. Crossref

6. Herman MC, Penninx J, Geomini PM, Mol BW, Bongers MY.

Choice of primary outcomes evaluating treatment for

heavy menstrual bleeding. BJOG 2016;123:1593-8. Crossref

7. Garg S, Anand T. Menstruation related myths in India: strategies for combating it. J Family Med Prim Care

2015;4:184-6. Crossref

8. The Lancet Child Adolescent Health. Normalising

menstruation, empowering girls. Lancet Child Adolesc

Health 2018;2:379. Crossref

9. Agampodi TC, Agampodi SB. Normalising menstruation,

empowering girls: the situation in Sri Lanka. Lancet Child

Adolesc Health. 2018;2:e16. Crossref

10. Wong WC, Li MK, Chan WY, et al. A cross-sectional

study of the beliefs and attitudes towards menstruation of

Chinese undergraduate males and females in Hong Kong. J

Clin Nurs 2013;22:3320-7. Crossref

11. Hald K, Lieng M. Assessment of periodic blood loss:

interindividual and intraindividual variations of pictorial

blood loss assessment chart registrations. J Minim Invasive

Gynecol 2014;21:662-8. Crossref

12. Reid PC, Coker A, Coltart R. Assessment of menstrual

blood loss using a pictorial chart: a validation study. BJOG

2000;107:320-2. Crossref