Hong Kong Med J 2023 Dec;29(6):548–50 | Epub 2 Nov 2023

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Tuberculosis of the knee as a great mimicker of

inflammatory arthritis: a case report

Holy MH Chan, MB, BS1; Henry Fu, MB, BS, FRCSEd (Orth)2; KY Chiu, MB, BS, FRCSEd (Orth)2

1 Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, School of Clinical Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr Henry Fu (drhfu@ortho.hku.hk)

Case presentation

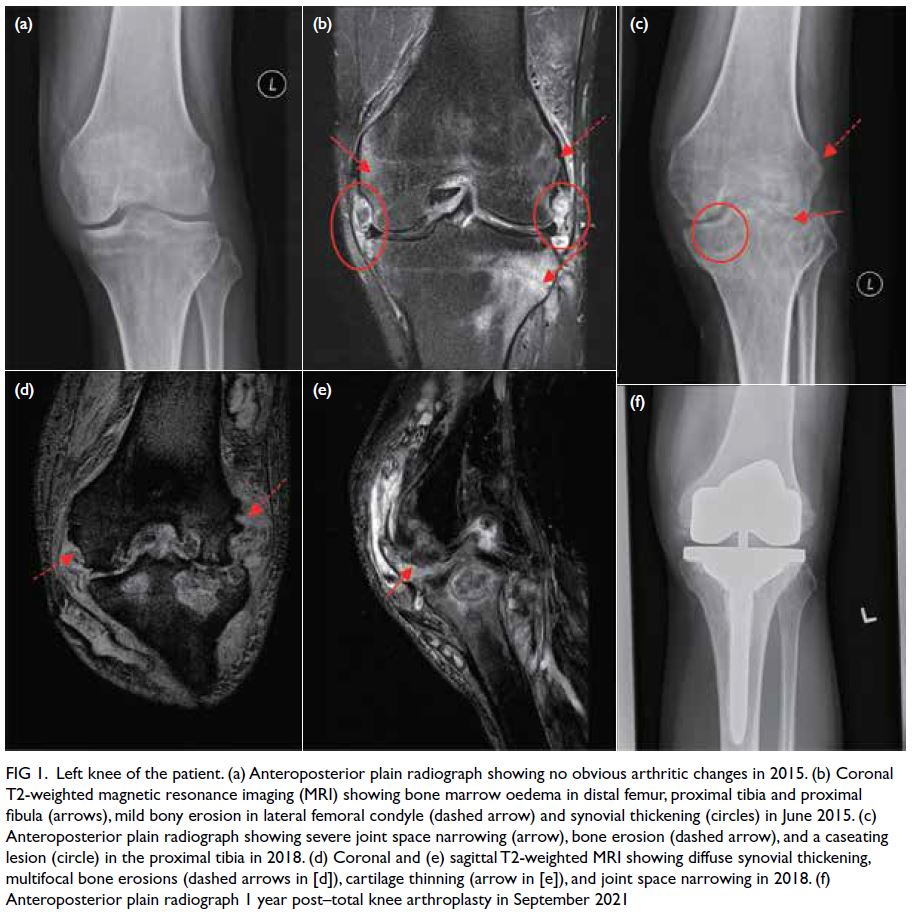

In January 2015, a 36-year-old man with good past

health presented to a hospital in Hong Kong with

intermittent low-grade fever and left knee effusion.

Physical examination revealed mild effusion,

erythema, warmth and tenderness over the left knee,

with 10˚ flexion contracture and flexion range up

to only 70˚. The levels of inflammatory markers (C-reactive

protein [CRP], erythrocyte sedimentation

rate [ESR], and antinuclear antibodies [ANA])

were elevated. Single-attempt arthrocentesis on

the affected knee yielded 1 mL of yellow fluid,

subsequently negative for Gram stain and culture

only. No obvious abnormalities were observed on

plain radiograph (Fig 1a), but magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI) in June 2015 demonstrated synovial

thickening, bone marrow oedema and subtle

cortical erosion at the lateral femoral condyle

(Fig 1b). Infection could not be excluded. Non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs were prescribed

for symptomatic control. The recurrent left knee

effusion persisted despite treatment, but no further

attempts at arthrocentesis were made until 2018.

Figure 1. Left knee of the patient. (a) Anteroposterior plain radiograph showing no obvious arthritic changes in 2015. (b) Coronal T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing bone marrow oedema in distal femur, proximal tibia and proximal fibula (arrows), mild bony erosion in lateral femoral condyle (dashed arrow) and synovial thickening (circles) in June 2015. (c) Anteroposterior plain radiograph showing severe joint space narrowing (arrow), bone erosion (dashed arrow), and a caseating lesion (circle) in the proximal tibia in 2018. (d) Coronal and (e) sagittal T2-weighted MRI showing diffuse synovial thickening, multifocal bone erosions (dashed arrows in [d]), cartilage thinning (arrow in [e]), and joint space narrowing in 2018. (f) Anteroposterior plain radiograph 1 year post–total knee arthroplasty in September 2021

In view of the joint stiffness, recurrent

knee effusion and persistently elevated levels of

inflammatory markers, the patient was referred to

a rheumatologist. A working diagnosis of atypical

rheumatoid arthritis (RA) was made despite

negative testing of anticyclic citrullinated peptide

antibody and rheumatoid factor. Sulphasalazine

was started in September 2015. Due to persistent

knee inflammation, intraarticular steroid injection

was given in November 2015 with limited effect.

Methotrexate and leflunomide were prescribed in

escalating doses. The patient was simultaneously

followed up by the orthopaedic department where

analgesics and physiotherapy were prescribed.

Interval MRI in December 2017 showed diffuse

synovial thickening, multifocal erosive changes and

bone marrow oedema in the proximal tibia, reported

to be in keeping with RA. Due to progressive

worsening of his knee, the patient attended the

private sector and was prescribed golimumab

biologics in February 2018.

In April 2018, a cystic swelling developed over

the posterolateral aspect of his left knee. Results of

aspiration yielded a positive acid-fast bacilli smear

and rapid cultures via Mycobacteria Growth Indicator

Tube grew Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Knee X-ray

revealed complete erosion of the medial and lateral

tibiofemoral joints (Fig 1c) while MRI showed

synovial thickening and intraosseous collection over

the medial and lateral tibia (Fig 1d and e). Disease-modifying

antirheumatic drugs were discontinued

and the patient commenced a 9-month course of

antituberculous drugs, namely isoniazid, rifampicin,

ethambutol, pyrazinamide, and pyridoxine.

Despite eventually controlling the tuberculosis

(TB), the patient’s knee function deteriorated and he

was referred to a tertiary hospital for consideration

of total knee arthroplasty (TKA). Preoperative

assessment revealed 60˚ ankylosis of the left knee

(Fig 2a) and healed sinus tracts without signs of

residual infection. Preoperative investigations

revealed normal ESR and CRP levels. Robotic

arm–assisted TKA with varus-valgus constrained

insert (Fig 1f) was performed in March 2020 and

the patient was prescribed a 12-month course of

antituberculous chemotherapy postoperatively.

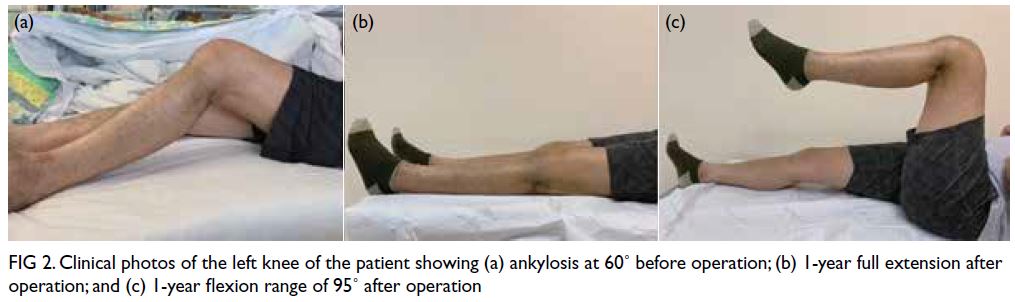

Postoperative range of motion (ROM) was 0˚ to 70˚

with 10˚ extension lag at 6 weeks due to quadriceps

atrophy. Manipulation under anaesthesia was

performed 3 months postoperatively to enhance

flexion range. A final ROM was of 0˚ to 95˚ was

achieved with no residual extension lag (Fig 2b and c). The latest follow-up 1.5 years postoperatively

showed stable ROM with no signs of reinfection. The

patient could walk unaided.

Figure 2. Clinical photos of the left knee of the patient showing (a) ankylosis at 60˚ before operation; (b) 1-year full extension after operation; and (c) 1-year flexion range of 95˚ after operation

Discussion

Tuberculosis of the knee is a rare form of

osteoarticular TB that is prone to misdiagnosis due

to its nonspecific presentation. It has an indolent

course compared with bacterial septic arthritis.

The clinical, radiological and laboratory features

mimic inflammatory arthritis such as RA. Both

diseases can present with monoarticular joint pain,

erythema, swelling, and stiffness. In knee TB, the Phemister triad of juxta-articular osteopenia, joint

space narrowing and peripheral bone erosions can

be observed on plain radiographs, but these can

also be evident in RA. Magnetic resonance imaging

features of TB include multifocal bone erosions,

articular surface destruction, cartilage erosions, and

marrow oedema.1 Similar laboratory results include

elevated white cell count (WCC) and percentage of

polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) in blood

and synovial fluid, and sustained elevation of ESR,

CRP and anti-nuclear antibody levels due to active

inflammation.

As in all circumstances of suspected infection,

a patient’s symptoms and risk factors such as

diabetes mellitus, RA and prior surgery should be

assessed.2 Local skin condition, effusion and ROM

should be noted on physical examination. Synovial fluid from arthrocentesis should be sent for total and

differential cell counts, biochemistry, microbiology,

crystals, and cytology. Total and differential

counts are helpful in differentiating infective and

inflammatory causes. Synovial fluid with WCC

of >50 000/mm3 and PMN level of >75% point

towards acute septic arthritis, while WCC of 2000 to

100 000/mm3 and PMN level of >50% suggest

inflammatory arthritis.3 Nonetheless in TB, the

WCC is typically in the inflammatory range of

10 000 to 20 000/mm.3 4 Joint aspirate should be sent

for fungal and acid-fast bacilli smear, culture and

TB–polymerase chain reaction (TB-PCR) to identify

atypical organisms in refractory patients. Although

the high specificity and shorter turnaround time

of TB-PCR can complement cultures and help

achieve an early diagnosis of TB, culture remains the gold standard to exclude TB infection due to its

higher sensitivity. When synovial fluid aspirate is

inadequate, repeated aspiration or even arthroscopic

synovial biopsy should be considered. Autoimmune

markers should be determined to exclude an

autoimmune cause. Serial knee X-rays and MRIs

should be taken regularly to monitor disease

progression. In equivocal cases, arthroscopic

synovial biopsy can be performed. A typical

histological finding of caseating granuloma with

lymphocytic infiltration is diagnostic of TB.

Although arthrocentesis is less invasive, it has a

lower diagnostic sensitivity (80%) for knee TB than

synovial biopsy (90%).4

Tuberculosis of the knee can be managed

conservatively by 12 to 18 months of antituberculous

chemotherapy if identified early. With increasing joint

damage, surgical intervention including debridement,

synovectomy and arthroplasty might be necessary.

The long disease course of joint destruction leads to

fibrosis and ankylosis of the knee joint. Total knee

arthroplasty is regarded as a primary treatment for

advanced TB of the knee. Sultan et al5 suggest TKA

be performed 1 to 5 years following eradication of TB

to minimise reinfection risk. Postoperatively, 12 to 18

months of antituberculous drug therapy is believed to

be highly effective in preventing recurrent infection,

possibly due to the biofilm-lacking nature and poor

metal adherence of TB.5

Robotic arm–assisted TKA with varus-valgus

constrained insert was performed for our patient.

The use of a constrained implant facilitated greater

coronal plane stability in view of the extensive bone

loss, ankylosis and ligamentous laxity secondary to

prolonged TB infection. Robotic arm–assisted TKA

was adopted since it enables higher accuracy in bone

cutting and implant positioning than manual TKA.6

This is important for a patient receiving TKA at a

young age.

Tuberculosis of knee is rarely documented in

Hong Kong. This case highlights the importance of

recognising TB as an important differential diagnosis

of inflammatory arthritis. Maintaining a high index of suspicion will facilitate early diagnosis, potentially

sparing the patient from joint destruction and TKA

at a young age. In the event of recurrent knee effusion,

synovial fluid samples should be sent for TB-PCR in

addition to cell count, cytology, bacterial, acid-fast

bacilli smear and cultures. Total knee arthroplasty

plays a significant role in restoration of acceptable

ROM in a knee with extensive bone erosion and

ankylosis.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: HMH Chan, H Fu.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: H Fu, KY Chiu.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: HMH Chan, H Fu.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: H Fu, KY Chiu.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and provided consent for publication of this case report.

References

1. Choi JA, Koh SH, Hong SH, Koh YH, Choi JY, Kang HS.

Rheumatoid arthritis and tuberculous arthritis:

differentiating MRI features. AJR Am J Roentgenol

2009;193:1347-53. Crossref

2. Margaretten ME, Kohlwes J, Moore D, Bent S. Does this

adult patient have septic arthritis? JAMA 2007;297:1478-88. Crossref

3. Horowitz DL, Katzap E, Horowitz S, Barilla-LaBarca ML.

Approach to septic arthritis. Am Fam Physician 2011;84:653-60.

4. Wallace R, Cohen AS. Tuberculous arthritis: a report of

two cases with review of biopsy and synovial fluid findings.

Am J Med 1976;61:277-82. Crossref

5. Sultan AA, Cantrell WA, Rose E, et al. Total knee

arthroplasty in the face of a previous tuberculosis infection of the knee: what do we know in 2018? Expert Rev Med

Devices 2018;15:717-24. Crossref

6. Hampp EL, Chughtai M, Scholl LY, et al. Robotic-arm

assisted total knee arthroplasty demonstrated greater

accuracy and precision to plan compared with manual

techniques. J Knee Surg 2019;32:239-50. Crossref