Hong Kong Med J 2023 Oct;29(5):462–5 | Epub 26 Jul 2023

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Occult intravascular large B-cell lymphoma presenting as postoperative thrombotic microangiopathy: a case report

WK Lam, MB, BS1; Edmond SK Ma, FHKCPath, MD2; SY Kong, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)3; SF Yip, FHKCPath, FHKCP1

1 Department of Clinical Pathology, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Clinical Laboratory, Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Pok Oi Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr WK Lam (lwk936@ha.org.hk)

Case presentation

In August 2017, a 59-year-old male with good past

health was admitted via the emergency department

with a 4-day history of abdominal distension and

epigastric pain. He had passed no stool for 2 days.

Physical examination revealed epigastric tenderness

and an empty rectum. Abdominal X-ray showed

intestinal obstruction and erect chest X-ray showed

no free gas under the diaphragm. Blood tests on

admission revealed a normal complete blood count

and acute renal failure (Table). The patient was

started on intravenous (IV) fluid and IV amoxicillin

and clavulanate. Urgent computed tomography (CT)

abdomen and pelvis with contrast showed acute

appendicitis with perforation and dilated small bowel

without an obvious transition point. Emergency

laparotomy revealed appendiceal diverticulitis with

walled-off localised abscess formation around the

appendix. The base of the appendix was healthy.

Microscopic examination of the appendix showed

dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltration in

periappendiceal fat and serositis, with no evidence

of malignancy, thrombosis or ischaemia.

Three days postoperatively, the patient

developed fever and hypotension and was given

IV piperacillin and tazobactam. There was no

organomegaly, lymphadenopathy or skin lesions on

physical examination. He became dull looking but

there was no focal neurological deficit. Septic workups

with blood and urine were negative. Sputum culture

showed Enterobacter cloacae, resistant to amoxicillin

and clavulanate. Widal test, Weil–Felix test, human

immunodeficiency virus serology and tests for viral

hepatitis were all negative. A second abdomen

CT showed no gross infective foci and only a few

subcentimetre lymph nodes. Plain brain CT showed

no focal intracranial lesions. Blood tests showed a

leukoerythroblastic blood picture and no circulating

abnormal cells, and acute hepatic and renal failure

with markedly elevated lactate dehydrogenase

level (Table). Fever did not abate despite IV

piperacillin and tazobactam, IV meropenem and IV anidulafungin were prescribed for support. In the

second week postoperatively, blood tests showed

progressive anaemia and thrombocytopenia with

microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia (MAHA)

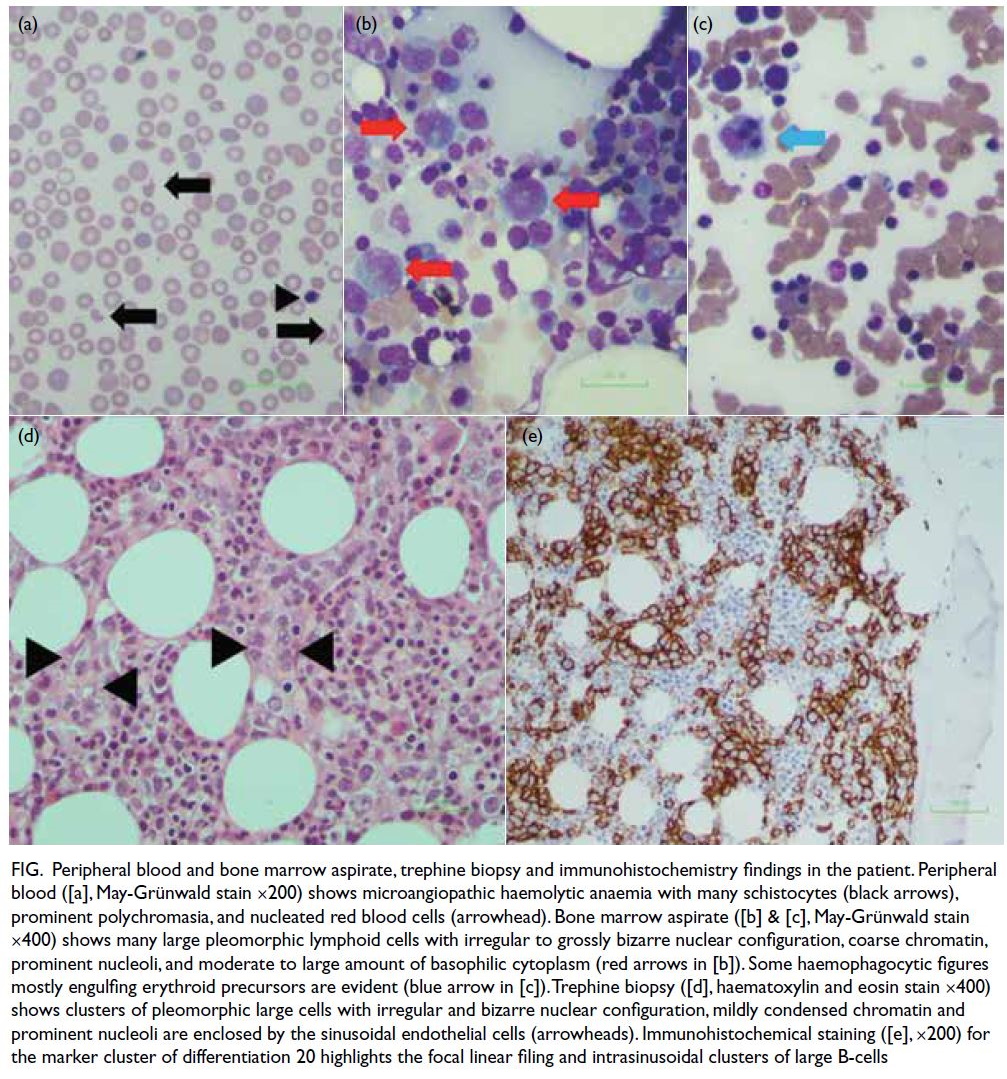

and a leukoerythroblastic blood picture (Table and

Fig a). Ferritin and triglyceride levels were markedly elevated.

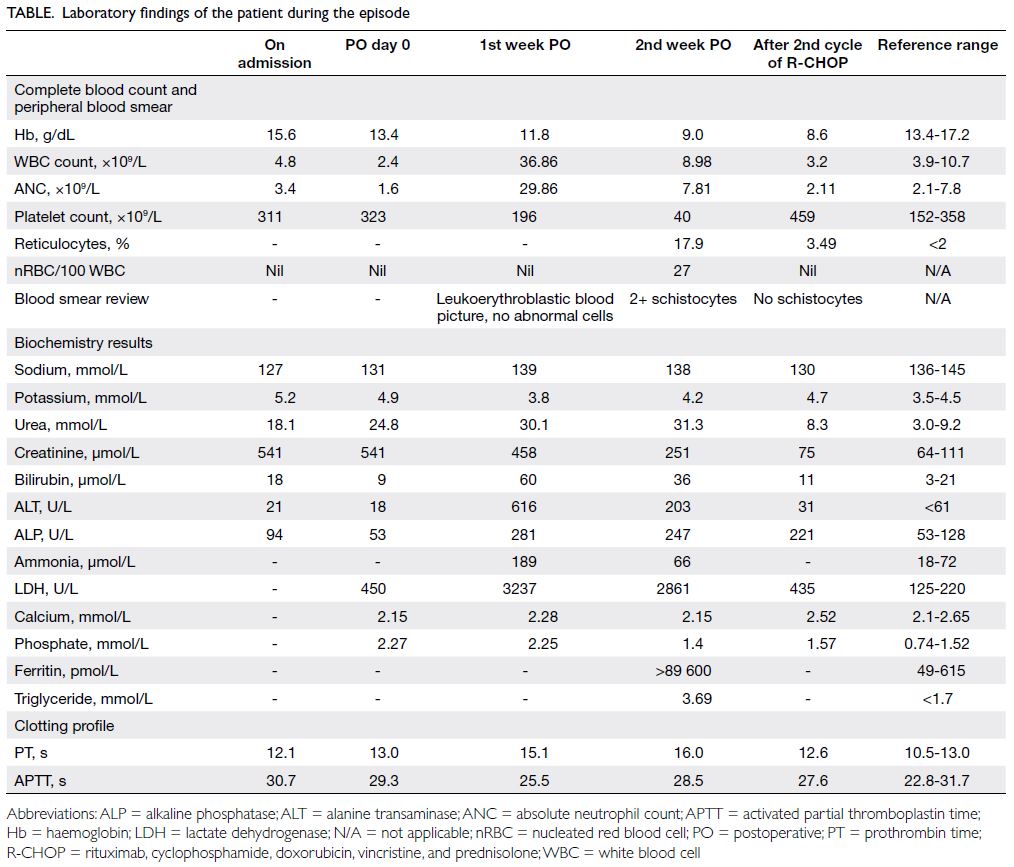

Figure. Peripheral blood and bone marrow aspirate, trephine biopsy and immunohistochemistry findings in the patient. Peripheral blood ([a], May-Grünwald stain ×200) shows microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia with many schistocytes (black arrows), prominent polychromasia, and nucleated red blood cells (arrowhead). Bone marrow aspirate ([b] & [c], May-Grünwald stain ×400) shows many large pleomorphic lymphoid cells with irregular to grossly bizarre nuclear configuration, coarse chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and moderate to large amount of basophilic cytoplasm (red arrows in [b]). Some haemophagocytic figures mostly engulfing erythroid precursors are evident (blue arrow in [c]). Trephine biopsy ([d], haematoxylin and eosin stain ×400) shows clusters of pleomorphic large cells with irregular and bizarre nuclear configuration, mildly condensed chromatin and prominent nucleoli are enclosed by the sinusoidal endothelial cells (arrowheads). Immunohistochemical staining ([e], ×200) for the marker cluster of differentiation 20 highlights the focal linear filing and intrasinusoidal clusters of large B-cells

Bone marrow biopsy was subsequently

performed and revealed many abnormal

pleomorphic large cells and haemophagocytosis

(Fig). In view of the fever of unknown origin,

cytopenia, hypertriglyceridaemia, markedly elevated

ferritin and haemophagocytosis in the bone marrow,

a diagnosis was reached of haemophagocytic

lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) and dexamethasone

15 mg daily orally and IV immunoglobulin

started. Trephine biopsy showed prominent

infiltration of pleomorphic large cells in focal

linear profiling and intrasinusoidal clusters. With

immunohistochemistry, the large cells were shown to

be positive for the markers cluster of differentiation

(CD20) [Fig e], CD30, CD5, and negative for activin

receptor-like kinase 1 and cyclin D1. Epstein-Barr

virus–encoded small RNA in situ hybridisation was

negative. A diagnosis was made of intravascular

large B-cell lymphoma (IVLBCL).

The ADAMTS13 (a disintegrin and

metalloproteinase with a thrombospondin type 1

motif, member 13) activity, antigen and autoantibody

assays were performed. There was severe reduction in

ADAMTS13 activity to 5% with ADAMTS13 antigen

level moderately reduced to 215 ng/mL (reference

range: 430-970) and autoantibody level at 2.5 units/mL (negative: <15). This confirmed ADAMTS13

deficiency and functional defect compatible with

the picture of malignancy-associated thrombotic

thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP). The patient was

prescribed immunochemotherapy with rituximab

(recombinant anti-CD20), cyclophosphamide,

vincristine and prednisolone, and rasburicase

for prophylaxis of tumour lysis syndrome.

Hydroxydaunorubicin was added in the second cycle of immunochemotherapy (R-CHOP, ie, a

combination of rituximab, cyclophosphamide,

doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone) after

which blood counts and liver and renal function test

results markedly improved (Table). The patient was

in complete remission after six cycles of R-CHOP.

Nonetheless he died of inoperable squamous cell

carcinoma of oesophagus 3 years after the diagnosis

of lymphoma.

Discussion

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma is a rare subtype

of extranodal large B-cell lymphoma characterised

by selective growth of neoplastic cells inside the

lumina of small- and medium-sized vessels, often

with an aggressive clinical course. There are two major patterns of clinical presentation: the classic

form with neurocutaneous involvement and the

haemophagocytic syndrome–associated form

with multiorgan failure, hepatosplenomegaly, and

pancytopenia. Diagnosis of IVLBCL is challenging

due to its variable presentation. Imaging may be

negative due to the lack of detectable tumour masses.

The initial presentation of this patient

was atypical, with appendiceal diverticulitis and

perforation. Review of the appendix specimen

confirmed the absence of lymphoma involvement.

There was no hepatosplenomegaly. The abrupt onset

of anaemia and thrombocytopenia with MAHA

raised the possibility of postoperative TTP. Patients

with postoperative TTP characteristically have a

normal complete blood count prior to surgery, but

subsequently show MAHA with thrombocytopenia about 5 to 9 days after surgery.1 Fever, renal

impairment, and neurological symptoms are

variably present. Nonetheless the abundance of

schistocytes and nucleated red cells in the blood

film and acute liver failure did not support a

diagnosis of postoperative TTP, warranting further

investigations.

Neoplastic cells may cause endothelial damage

and result in release of ultra-large von Willebrand

factor multimers. Autoantibodies against

ADAMTS13 may also play a role in pathogenesis,

leading to platelet activation and thrombotic

microangiopathy.2 In our case, ADAMTS13 activity

was markedly reduced at 5%, unusually low for malignancy-associated TTP (median ADAMTS13 activity: 50%).3 Some secondary TTP cases have been reported with markedly reduced ADAMTS13

activity4 but the significance is uncertain. The

ADAMTS13 activity was also disproportionately

lower than the antigen level, indicating a functional

defect that may be seen in acquired TTP. Negative

autoantibody against ADAMTS13 suggests against

a diagnosis of idiopathic TTP. Distinguishing

malignancy-associated TTP from idiopathic or

postoperative TTP is important since therapeutic

plasma exchange is effective in idiopathic or

postoperative TTP but not in malignancy-associated

TTP.

Although the anaemia and thrombocytopenia

could be explained by the MAHA, hyperferritinaemia,

hypertriglyceridaemia and haemophagocytosis in

bone marrow were compatible with HLH. Of note, the

current diagnostic criteria for HLH were originally

proposed for diagnosis in paediatric patients.5 Criteria

cut-offs such as a ferritin level >500 ng/mL may not

be applicable in adults where there are many other

reasons for such a high level. Bone marrow biopsy is

the preferred investigation in the diagnosis of HLH

and IVLBCL. A high index of suspicion should be

maintained since the peripheral blood may not show

abnormalities specific to these diagnoses.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: WK Lam.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: WK Lam, ESK Ma, SF Yip.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: WK Lam.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: WK Lam, ESK Ma, SF Yip.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and has provided informed consent for all treatments

and procedures, and consent for publication.

References

1. Eskazan AE, Buyuktas D, Soysal T. Postoperative thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Surg Today 2015;45:8-16. Crossref

2. Sill H, Höfler G, Kaufmann P, et al. Angiotropic large cell lymphoma presenting as thrombotic microangiopathy (thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura). Cancer 1995;75:1167-70. Crossref

3. George JN. Systemic malignancies as a cause of unexpected microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia. Oncology (Williston Park) 2011;25:908-14.

4. Hassan S, Westwood JP, Ellis D, et al. The utility of ADAMTS13 in differentiating TTP from other acute thrombotic microangiopathies: results from the UK TTP Registry. Br J Haematol 2015;171:830-5. Crossref

5. Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. HLH-2004: diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007;48:124-31. Crossref