Emphysematous pyelonephritis (class IIIa) managed with antibiotics alone

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144301

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Emphysematous pyelonephritis (class IIIa) managed with antibiotics alone

Vivek Chauhan, MD; Rajesh Sharma, MD

Department of Medicine, Dr RPGMC Kangra at Tanda, Kangra, 176001, Himachal Pradesh, India

Corresponding author: Dr Vivek Chauhan (drvivekshimla@yahoo.com)

Abstract

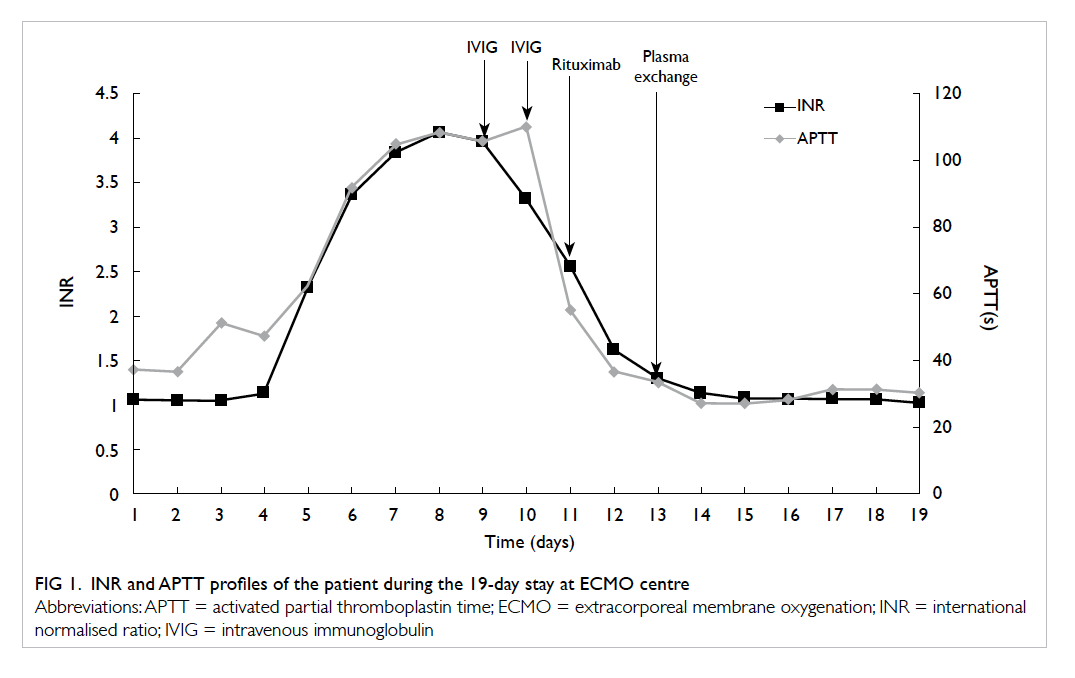

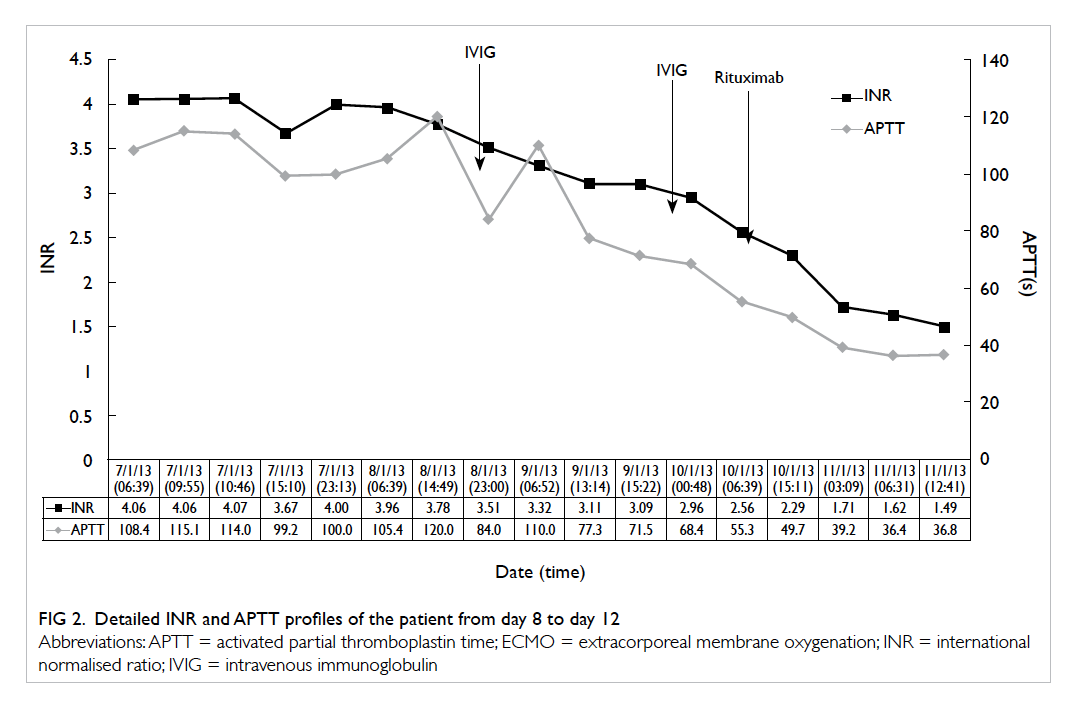

A 54-year-old male with long-standing diabetes

presented with vague left flank pain for 5 days

with uncontrolled blood glucose. The patient was

commenced on insulin and injectable ceftriaxone

empirically, for possibly acute pyelonephritis.

Ultrasound examination revealed extensive

emphysematous pyelonephritis of upper half of

left kidney with involvement of perinephric space.

Computed tomography of abdomen confirmed the

diagnosis of emphysematous pyelonephritis which

was categorised as class IIIa. The recommended

treatment for class IIIa emphysematous

pyelonephritis is nephrectomy but the patient refused

to give consent for surgery or even percutaneous

drainage. Thus, the patient was continued on medical

management alone and surprisingly showed marked

recovery over the next few days. There were no new

complications, and the patient was discharged after

2 weeks of antibiotics with 2 more weeks of oral

antibiotics. After 4 months, the ultrasound showed

normal kidneys. We present this case because it

adds to the little existing evidence that conservative

management can successfully cure patients with

class IIIa emphysematous pyelonephritis, although

supplementation with percutaneous drainage would

have been better in this case.

Introduction

Emphysematous pyelonephritis (EPN) is a

complication seen in patients with long-standing

diabetes and is characterised by formation of gas

in the renal parenchyma.1 Such gas may extend

into the peri-nephric or para-renal spaces and

additionally in advanced case, there may be bilateral

and extensive involvement.1 The primary cause

of EPN is urinary tract infection caused by either

Gram-negative organisms or anaerobes in some

cases. The diagnosis of EPN is confirmed by non-contrast

computed tomography (CT) and treatment

is usually based on the CT classification. In the

case of class IIIa EPN, the current recommended

treatment of choice is nephrectomy or percutaneous

drainage. Herein, however, we managed our patient

with class IIIa EPN conservatively with only medical

management, without percutaneous drainage or

even haemodialysis.

Case report

In August 2010, a 54-year-old male with diabetes

for the past 20 years presented to the Dr Rajendra

Prasad Government Medical College in Himachal

Pradesh, India. His chief complaints were pain in

left flank for 5 days and fever for 1 day. The symptom

of pain was gradually progressive, continuous type

localised in left flank. The patient developed fever on

the fourth day which was recorded as 102°F (38.9°C).

He was given ornidazole and ofloxacin tablets orally

at a primary health centre and was then referred to

our medical department because of uncontrolled

blood glucose. He reported a history suggestive of

osmotic symptoms and burning micturition for 5

days, and there were no other significant present

or past complaints. The vital signs showed blood

pressure of 90/60 mm Hg at presentation, pulse rate

of 106 beats/min, respiratory rate of 16 breaths/min, and

temperature of 103°F (39.4°C) was recorded. On

examination, the patient was conscious, oriented,

and there was tenderness in the left renal angle, but

all the other systems were normal. The biochemistry

results showed a haemoglobin level of 101 g/L

(reference range, 120-150 g/L), total leukocyte count

of 17 700/mm3, neutrophils of 88%, and erythrocyte

sedimentation rate of 68 mm/h (reference range,

0-22 mm/h), with normal platelet counts and liver

functions. Metabolic control was very poor with

glycated haemoglobin level of 12.8%, urea of 19.27

mmol/L (reference range, 4-8.3 mmol/L), and serum

creatinine of 132.6 µmol/L (reference range, 50-110 µmol/L). Urine examination showed no albumin,

traces of sugar, while urine microscopy showed

15 to 20 pus cells per high-power field, and therefore

urine culture and sensitivity was ordered. However,

the urine and blood culture reports later turned out

to be sterile.

The patient was managed for uncontrolled

blood glucose and a possible diagnosis of acute

pyelonephritis of the left kidney was made clinically.

He was started on human mixed insulin along with

ceftriaxone (1 g administered intravenously every

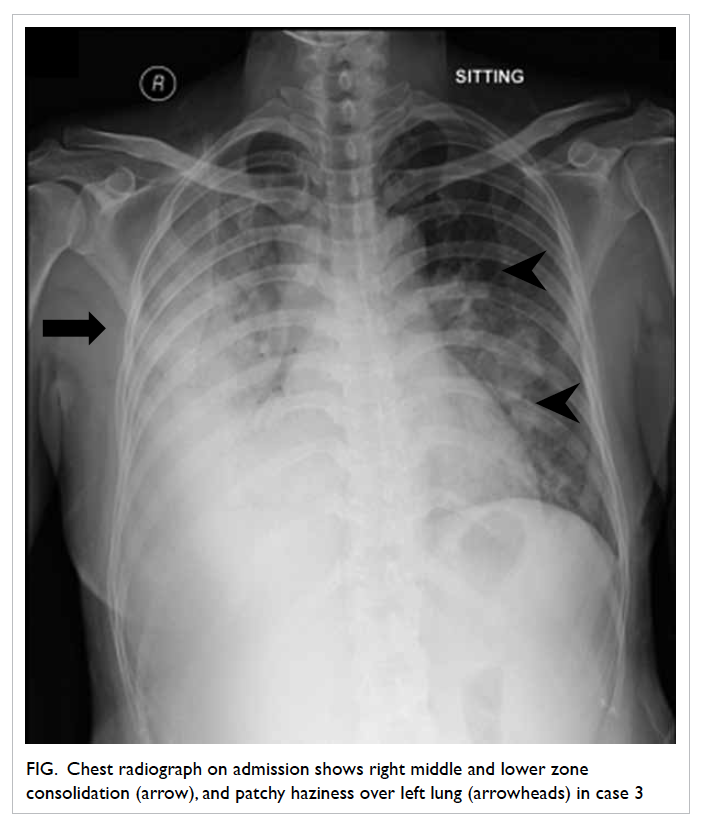

12 hours). Chest X-ray showed raised left dome of

diaphragm. Ultrasound examination of abdomen

revealed EPN of left kidney with destruction of

upper portion and extending into the perinephric

space near the upper pole. The treatment given was

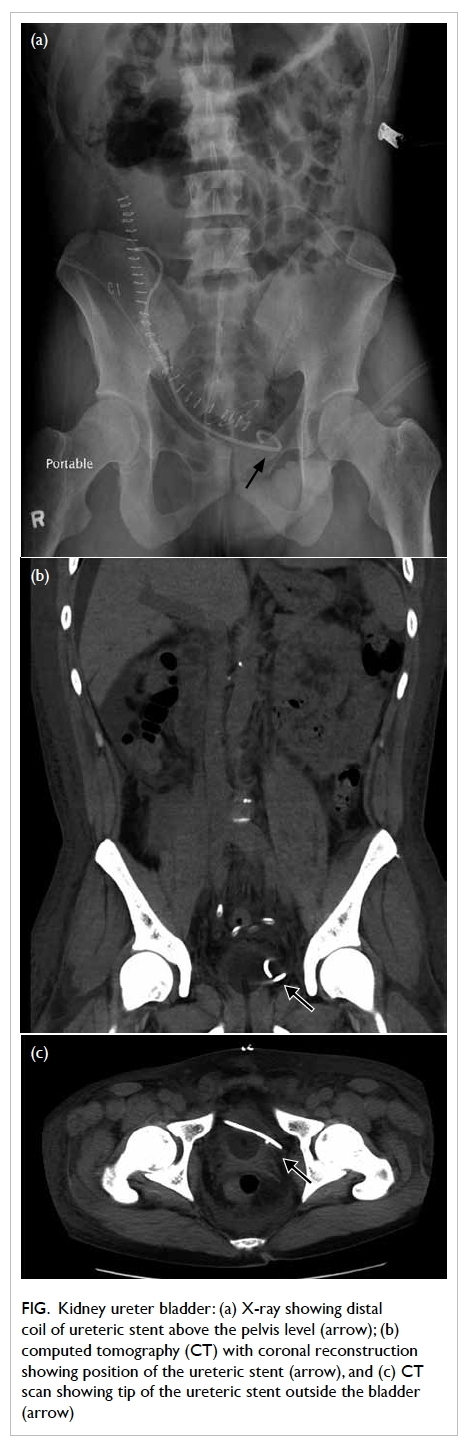

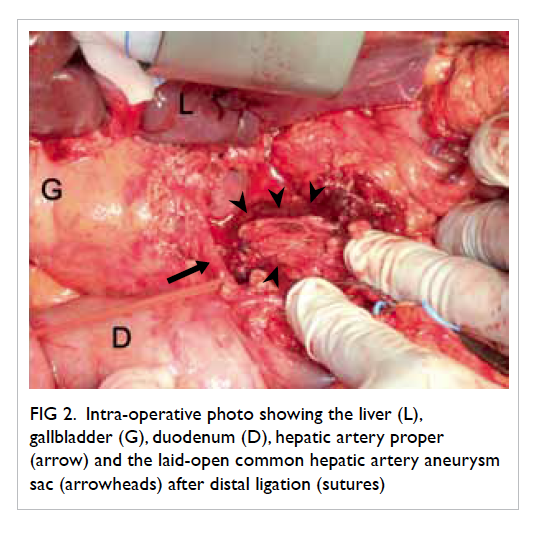

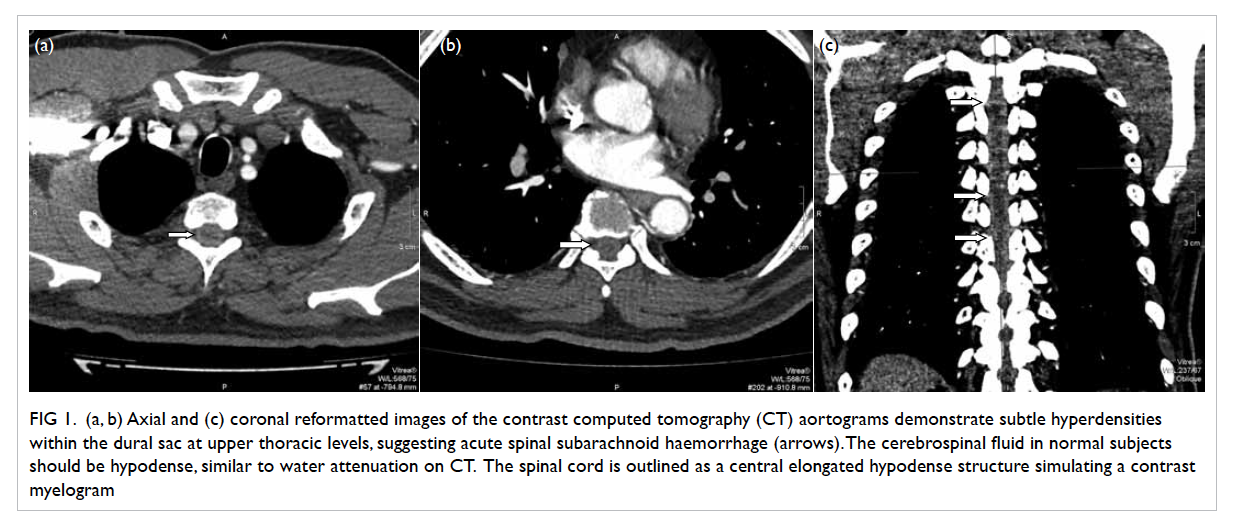

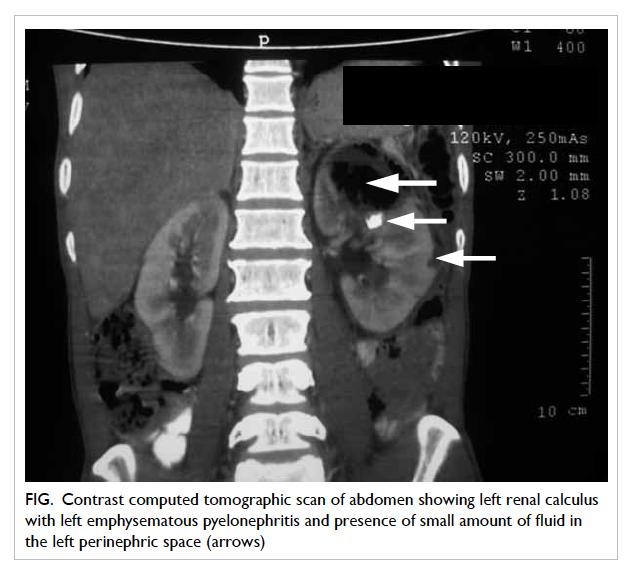

continued and the abdominal CT scan revealed evidence of

a small renal calculus on the left side with extensive

EPN of the left kidney and the presence of small

amount of fluid in the left perinephric space (Fig). In

this patient, the CT classification was class IIIa EPN.

Figure. Contrast computed tomographic scan of abdomen showing left renal calculus with left emphysematous pyelonephritis and presence of small amount of fluid in the left perinephric space (arrows)

With regard to further management, we gave an

option of nephrectomy to the patient, but he refused

to give consent for any surgical intervention. The

patient refused even for percutaneous nephrostomy,

so we continued with medical management alone. To

our surprise, throughout the hospital stay, the patient

remained afebrile and fully conscious. He showed a

steady recovery in clinical and laboratory parameters

without any new complaints or complications.

After 1 week of insulin and antibiotic (ceftriaxone)

treatment, his renal functions remained normal

with a serum creatinine of 106.1 µmol/L and blood

glucose was adequately controlled with human

mixed insulin injections over the next few days.

The patient was started on intravenous ceftriaxone

empirically on admission and this was continued for

a total of 2 weeks. During this period, the patient

became fully active and mobile. Due to absence of

any complications or features of sepsis after 2 weeks

of treatment, the patient was discharged on oral

antibiotics for a further 2 weeks. After 4 months,

ultrasound examination showed normal kidneys and

even the small calculus had disappeared.

Discussion

Emphysematous pyelonephritis is a well-known

condition which mainly affects the diabetic

population (90%) and seen in patients with chronic

diabetes.1 Some interesting facts about EPN are that

it has a strong female preponderance with female-to-male

ratio of 5:1, mean age of occurrence is around

the fifth decade, and most often it involves left kidney

in almost 60% of cases.1 The gas contains carbon

dioxide mainly because of bacterial fermentation

of glucose along with some hydrogen and nitrogen.

Presentation is often vague with non-specific

abdominal pain, fever, and tenderness in the renal

angle.1

Since most cases are sporadic and spread over

time, it is not easy to formulate definitive guidelines

for all cases of EPN. The best evidence available for

EPN is dependent on a few large prominent studies

by Huang and Tseng2 in 2000 with 48 patients and

a review by Pontin and Barnes1 in 2009 with 52

patients. Such studies serve as a good guide for the

rest of the world, but may suffer from bias from the

treating physicians and surgeons. So it is prudent to

report all cases of EPN with details of presentation,

extent of involvement, line of management, and

outcomes.

The medical management of EPN was

proposed a long time ago when it was first described

by Schultz and Klorfein in 1962.3 In fact, in their

report it was stated that “Vigorous treatment of

uncontrolled diabetes and the use of appropriate

antibiotics, avoiding anaesthesia and surgery seems

a more rational approach.”3

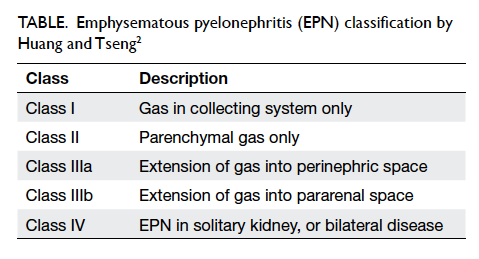

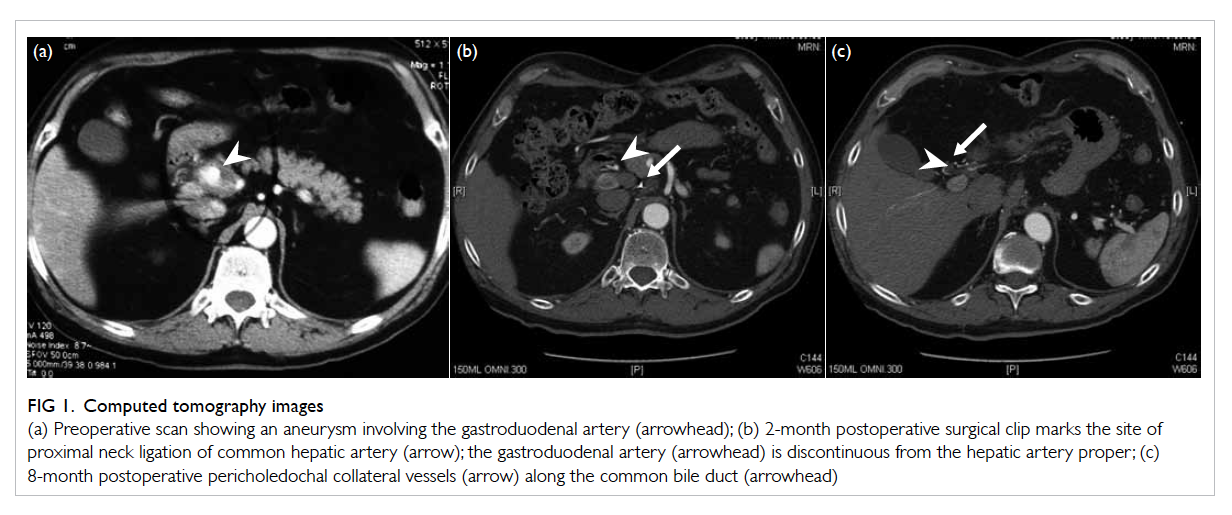

The current management recommendations

are based on the CT-based classification used by

Huang and Tseng2 in which they divide EPN into

classes I, II, IIIa, IIIb, and IV (Table).

Class I and II EPN can be managed by medical

therapy alone or combined with percutaneous

drainage. Huang and Tseng2 found that class IIIa EPN

showed a 71% failure rate following percutaneous

drainage with a 29% mortality rate, and those

belonging to class IIIb had a 30% failure rate with

a 19% mortality rate. Thus surgery became the

norm for extensive disease except where there was

a single kidney or bilateral involvement. Unilateral

nephrectomy can be done with a low mortality risk

in most centres.1

The most recent updates, however, recommend

a more conservative approach. Recently, reports of

successful management using percutaneous drainage

and medical management alone have started coming

from across the world even with bilateral and

extensive disease.4 5 6 A recent case series describes

eight cases of EPN with medical management alone.6

Of these eight cases, four were class IV EPN, five

cases required haemodialysis, whereas four needed

percutaneous drainage. The authors successfully

used injections of imipenem for 10 days in five

patients, cefoperazone + sulbactam for 14 days

in two patients, and piperacillin + tazobactam for 14

days in one patient.6 Antibiotics that are effective in

treating EPN include quinolones, beta-lactamase

inhibitors, cephalosporins, and aminoglycosides,

alone or in combinations mainly to cover Gram-negative

bacteria like Escherichia coli, Klebsiella

pneumoniae, Proteus spp, Streptococcus spp,

Pseudomonas spp, and anaerobes like Bacteroides

fragilis, and Clostridium septicum.7 8

The reason for successful shift in management

is probably because nowadays EPN gets picked up

early on CT showing very small air pockets. Such

patients are therefore more likely to respond to

conservative management. Even for larger EPN,

percutaneous drainage rather than nephrectomy can

be the standard of care in a majority of patients.1

Since India is one of the epicentres of diabetes

epidemic, we wish to emphasise that systematic

reporting of all EPN cases from this region can aid in

formulating guidelines, especially for poor resource

settings like ours. Most of our cases go unreported

due to lack of proper record maintenance. Our

patient had received ciprofloxacin tablets for 5 days

before presenting to our hospital. Early initiation of

antibiotics may have limited the progress of EPN

in this patient and may have also been responsible

for the sterile cultures that were reported. The

patient had long-standing diabetes and also had

a renal calculus, both of which can predispose to

infection and subsequently lead to EPN. The patient

was categorised as class IIIa EPN, who responded

exceptionally well to antibiotics alone and had

complete resolution of EPN on follow-up.

In conclusion, this is a rare case report because

our patient recovered without drainage, surgery, or

even haemodialysis. There have been reports that

in class IIIa EPN that medical management alone

with percutaneous drainage has a 92% failure rate.2

We wish to emphasise sensitisation of treating

physicians regarding early investigations using

contrast CT scan in diabetes patients with fever,

renal angle tenderness, and vague abdominal pain.

We do not recommend medical treatment for all

such cases, but follow-up should be based upon

patient’s response to the initial treatment.

References

1. Pontin AR, Barnes RD. Current management of

emphysematous pyelonephritis. Nat Rev Urol 2009;6:272-9. Crossref

2. Huang JJ, Tseng CC. Emphysematous pyelonephritis:

clinicoradiological classification, management, prognosis,

and pathogenesis. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:797-805. Crossref

3. Schultz EH Jr, Klorfein EH. Emphysematous pyelonephritis.

J Urol 1962;87:762-6.

4. Flores G, Nellen H, Magaña F, Calleja J. Acute bilateral

emphysematous pyelonephritis successfully managed by

medical therapy alone: a case report and review of the

literature. BMC Nephrol 2002;3:4. Crossref

5. Tahir H, Thomas G, Sheerin N, Bettington H, Pattison

JM, Goldsmith DJ. Successful medical treatment of acute

bilateral emphysematous pyelonephritis. Am J Kidney Dis

2000;36:1267-70. Crossref

6. Kolla PK, Madhav D, Reddy S, Pentyala S, Kumar

P, Pathapati RM. Clinical profile and outcome of

conservatively managed emphysematous pyelonephritis.

ISRN Urol 2012;2012:931982. Crossref

7. Chen MT, Huang CN, Chou YH, Huang CH, Chiang

CP, Liu GC. Percutaneous drainage in the treatment of

emphysematous pyelonephritis: 10-year experience. J Urol

1997;157:1569-73. Crossref

8. Shokeir AA, El-Azab M, Mohsen T, El-Diasty T.

Emphysematous pyelonephritis: a 15-year experience with

20 cases. Urology 1997;49:343-6. Crossref