DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144235

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Chinese talismans as a source of lead exposure

CK Chan, Dip Clin Tox, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)1; CK Ching, FRCPA, FHKAM (Pathology)2; FL Lau, FRCS (Edin), FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)1; HK Lee, MSc3

1 Hong Kong Poison Information Centre, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

2 Hospital Authority Toxicology Reference Laboratory, Princess Margaret

Hospital, Laichikok, Hong Kong

3 Department of Clinical Pathology, Tuen Mun Hospital, Tuen Mun, Hong

Kong

Corresponding author: Dr CK Chan (chanck3@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

We describe a case of lead exposure after prolonged

intake of ashes from burnt Chinese talismans. A

41-year-old woman presented with elevated blood

lead level during screening for treatable causes of

progressive weakness in her four limbs, clinically

compatible with motor neuron disease. The source of

lead exposure was confirmed to be Chinese talismans

obtained from a religious practitioner in China. The

patient was instructed to burn the Chinese talismans

to ashes, and ingest the ashes dissolved in water, daily

for about 1 month. Analysis of the Chinese talismans

revealed a lead concentration of 17 342 µg/g (ppm).

Case report

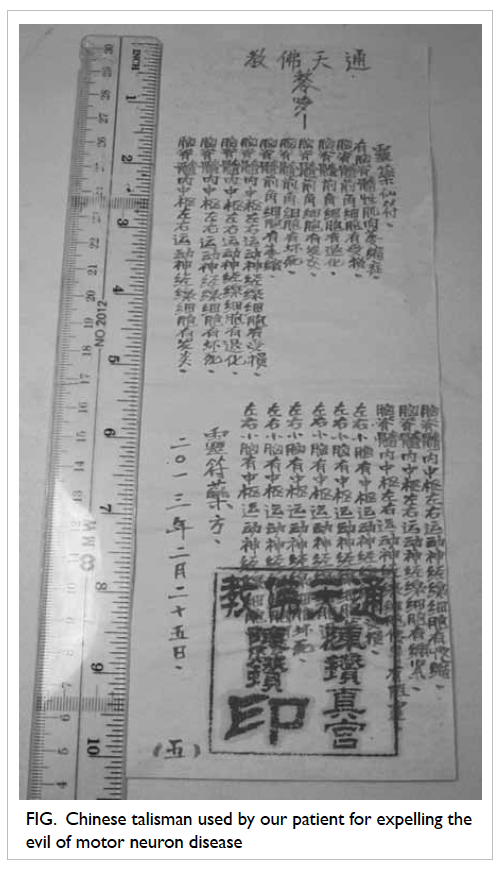

Chinese talisman is a religious handwriting or

calligraphy which is believed to possess magical

powers for expelling evils and avoiding misfortune.

It is usually obtained from Daoism religious

practitioners.1 Some people believe that consuming

burnt Chinese talisman ashes dissolved in water is

useful in curing diseases. Here we report a case of

lead exposure after prolonged intake of ashes from

burnt Chinese talismans.

The patient was a 41-year-old woman. She

presented with progressive weakness of four limbs

with signs of upper motor neuron disease (MND)

since March 2012. Electromyogram findings were

compatible with diffuse anterior horn cell disorder.

Motor neuron disease was clinically diagnosed by

the treating neurologist. Knowing that no curative

option exists for MND, she started using Chinese

talismans obtained from a religious practitioner in

China (Fig). She was instructed to burn the Chinese

talismans to ashes and ingest the ashes dissolved in

water 3 times daily. She continued this practice

for about 1 month, until she believed that it was not

useful for her illness. She was then found to have

elevated blood lead level (BLL) of 1.83 µmol/L or

38 µg/dL (reference level, <0.48 µmol/L or <10 µg/dL)

during routine screening for treatable causes of

neuropathy. Her blood mercury level was normal.

Blood lead level rechecked 2 weeks later was 2.61

µmol/L (54 µg/dL). Other than the neurological

symptoms, the patient had no other clinical features

of lead poisoning such as elevated blood pressure,

anaemia with basophilic stippling, or gastro-intestinal

symptoms. She was subsequently referred

to the poison centre for assessment of lead exposure.

Detailed enquiry did not point to any well-known

source of lead exposure. She had been working as a cleansing worker in a food-processing

factory until she became sick. She had never worked

in any mining industry, metal refinery, glass factory,

or battery factory. She did not have a history of

gunshot wound, nor did she have exposure to lead

paint or ceramic craft. Her husband had normal BLL.

Abdominal X-ray did not reveal lead-containing

foreign materials in the gastro-intestinal tract. She

had used several health supplements including

vitamin preparations and ginkgo biloba extract. The

lead levels of these health supplements were found

to be undetectable. Our suspicions were aroused

when the patient reported that the Chinese talismans were supposed

to be written with cinnabar (硃砂), a red mercuric sulfide containing ore. Substitution of

cinnabar with another red mineral, minium (鉛丹, lead tetroxide), when used as Chinese medicine, has

been reported.2 3 Analysis of the Chinese talisman

by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry

revealed a very high lead concentration of 17 342 µg/g,

thus confirming the source of lead exposure.

Her BLL was 2.82 µmol/L (59 µg/dL) about

2 months after stopping the use of the Chinese

talismans. Although her neurological presentation

was not typical of lead neurotoxicity,4 there have been

case reports of lead poisoning mimicking MND.5 6

Moreover, an animal study showed that anterior

horn cells were sensitive to lead toxicity.7 Chelation

therapy with succimer (dimercaptosuccinic acid

[DMSA]) was started in view of these possibilities. A

standard course of DMSA 10 mg/kg 3 times daily

for 5 days, followed by 2 times daily for 14 days was

given.8 Her BLL taken at 6 weeks after completion

of DMSA course was 0.7 µmol/L (14 µg/dL). No

improvement of limb weakness was observed in the

patient 8 weeks after completion of DMSA course.

Further courses of DMSA were judged unnecessary.

The patient continued to have medical follow-up for

MND.

Discussion

This case illustrates a rare source of lead exposure

related to the religious practice of consuming burnt Chinese talisman ashes dissolved in water to

cure a disease. The list of common sources of lead

exposure such as occupational, environmental and

recreational ones, can be found in general medicine

and toxicology textbooks.4 Uncommon and exotic

sources reported in the literature usually involve

traditional medicines, cosmetics, and ingestion of

lead-containing foreign bodies (eg bullet, necklace,

fishing sinker).9 10 11

The use of cinnabar has been described

in Daoism alchemy and traditional Chinese

medicine.12 13 Both lead tetroxide and cinnabar

are red in colour with similar appearance, and

substitution of cinnabar with lead tetroxide in

Chinese medicine has been reported.3 The reason for

the substitution is uncertain but it could be due to

mixing up or related to the higher cost of cinnabar.2

The toxicity of lead tetroxide is known since ancient

times in China. Lead poisoning related to the topical

use of lead tetroxide in Chinese medicine for chronic

ulcer has been reported.12

Before the era of molecular genetics, lead

poisoning was believed to be one of the possible

causes of MND.14 15 Nowadays, with the identification

of different genes implicated in MND, it is believed

that genetic causes account for a significant

proportion of the cases.16 Neurological presentation

of mild lead poisoning includes tiredness, headache,

insomnia, memory loss, and lessened interest in

leisure activities. In severe cases, coma, seizures,

and peripheral neuropathy are possible.4 Lead-induced

peripheral neuropathy is typically a pure

motor disorder with features including footdrop and

wristdrop.4 Severe form of lead-induced peripheral

neuropathy has been reported in causing generalised

weakness mimicking MND.5 6 Unlike MND, lead-induced

peripheral neuropathy is associated with

increased body burden of lead, a temporal sequence

between lead exposure and progression of muscle

weakness, clinical stabilisation or remission after

removal from exposure, and systemic involvement

with other features of lead poisoning such as anaemia

and gastro-intestinal disturbance.17

Chelation therapy is usually not indicated

in asymptomatic adults with BLL of <3.36 µmol/L

(70 µg/dL).4 18 Nevertheless, there is no established

action level in the presence of underlying MND. As

lead-induced peripheral neuropathy is a possible

reversible cause in this patient, chelation therapy

was offered despite only a moderate increase in BLL.

The lack of clinical improvement after cessation

of exposure and normalisation of BLL made the

diagnosis of lead-induced peripheral neuropathy

unlikely in this patient.

Conclusion

Ingestion of burnt Chinese talisman is a possible

source of lead exposure. This rare source of lead poisoning should be considered in a specific group

of patients believing in this religious practice.

References

1. Wu YM. Talismans and spells. Available from: http://taiwanpedia.culture.tw/en/content?ID=2073. Accessed 18

Sep 2013.

2. Ban of cinnabar in Chinese medicine use in Taiwan [in

Chinese]. Available from: http://www.twtcm.com.tw/law-content.php?id=9. Accessed 26 Jun 2014.

3. Lead and mercury content of proprietary Chinese medicine

Babao powder [in Chinese]. Available from: http://www.consumers.org.tw/unit412.aspx?id=459. Accessed 11 Dec

2013.

4. Nelson LS, Lewin NA, Howland MA, Hoffman RS,

Goldfrank LR, Flomenbaum NE. Goldfrank’s toxicological

emergencies, 9th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical;

2011: 1266-83.

5. Boothby JA, DeJesus PV, Rowland LP. Reversible forms

of motor neuron disease. Lead “neuritis”. Arch Neurol

1974;31:18-23. CrossRef

6. Rubens O, Logina I, Kravale I, Eglîte M, Donaghy M.

Peripheral neuropathy in chronic occupational inorganic

lead exposure: a clinical and electrophysiological study. J

Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001;71:200-4. CrossRef

7. Yokoyama K, Araki S, Akabayashi A, Kato T, Sakai T, Sato

H. Alternation of glucose metabolism in the spinal cord

of experimental lead poisoning rats: microdetermination

of glucose utilization rate and distribution volume. Ind

Health 2000;38:221-3. CrossRef

8. Rogan WJ, Dietrich KN, Ware JH, et al. The effect of

chelation therapy with succimer on neuropsychological

development in children exposed to lead. N Engl J Med

2001;344:1421-6. CrossRef

9. Karri SK, Saper RB, Kales SN. Lead encephalopathy due to

traditional medicines. Curr Drug Saf 2008;3:54-9. CrossRef

10. Levin R, Brown MJ, Kashtock ME, et al. Lead exposures in

U.S. children, 2008: implications for prevention. Environ

Health Perspect 2008;116:1285-93. CrossRef

11. St Clair WS, Benjamin J. Lead intoxication from ingestion

of fishing sinkers: a case study and review of the literature.

Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2008;47:66-70. CrossRef

12. Wu ML, Deng JF, Lin KP, Tsai WJ. Lead, mercury, and

arsenic poisoning due to topical use of traditional Chinese

medicines. Am J Med 2013;126:451-4. CrossRef

13. Hsiao CM. Dao of alchemy. Available from: http://taiwanpedia.culture.tw/en/content?ID=2081. Accessed 18

Sep 2013.

14. Lead and motor neurone disease. BMJ 1978;2:308. CrossRef

15. Kamel F, Umbach DM, Munsat TL, Shefner JM, Hu

H, Sandler DP. Lead exposure and amyotrophic lateral

sclerosis. Epidemiology 2002;13:311-9. CrossRef

16. Rademakers R, van Blitterswijk M. Motor neuron disease

in 2012: novel causal genes and disease modifiers. Nat Rev

Neurol 2013;9:63-4. CrossRef

17. Windebank A J, McCall JT, Dyck PJ. Metal neuropathy:

peripheral neuropathy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Sanders;

1993: 1549-70.

18. Porru S, Alessio L. The use of chelating agents in

occupational lead poisoning. Occup Med (Lond)

1996;46:41-8. CrossRef