Minimally invasive enteroscopically guided small bowel resection

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144270

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Minimally invasive enteroscopically guided small bowel resection

Tommy CH Man, MB, BS;

KC Ng, MB, BS;

KW Wong, MB, BS;

Francis PT Mok, MB, BS

Department of Surgery, Caritas Medical Centre, Shamshuipo, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Tommy CH Man (manchunhin@gmail.com)

Abstract

Localisation of small bowel pathology is often

difficult, especially intramural small bowel lesions.

Even with the use of laparoscopy, visualisation of

small bowel lesion is not always possible. The most

accurate method to identify such a lesion is by

laparotomy with direct visualisation and palpation

of the lesion. However, the recent trend in surgical

development aims for minimally invasive procedures

while keeping the excision of surgical pathology

safe and complete, with less surgical trauma. This

report illustrates a case of minimally invasive

enteroscopically guided small bowel resection.

Case report

A 64-year-old male with a history of hepatic

carcinosarcoma had his right hemihepatectomy

done in 2011. The resection margins were clear and

interval computed tomography (CT) scans did not

reveal any recurrence.

One year after the surgery he was admitted

for complaints of non-specific abdominal pain,

melena, and dizziness. On admission, the

haemoglobin level was only 50 g/L although his

oesophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy

were normal. Capsule endoscopy was performed

and this showed a fungating tumour in the jejunum

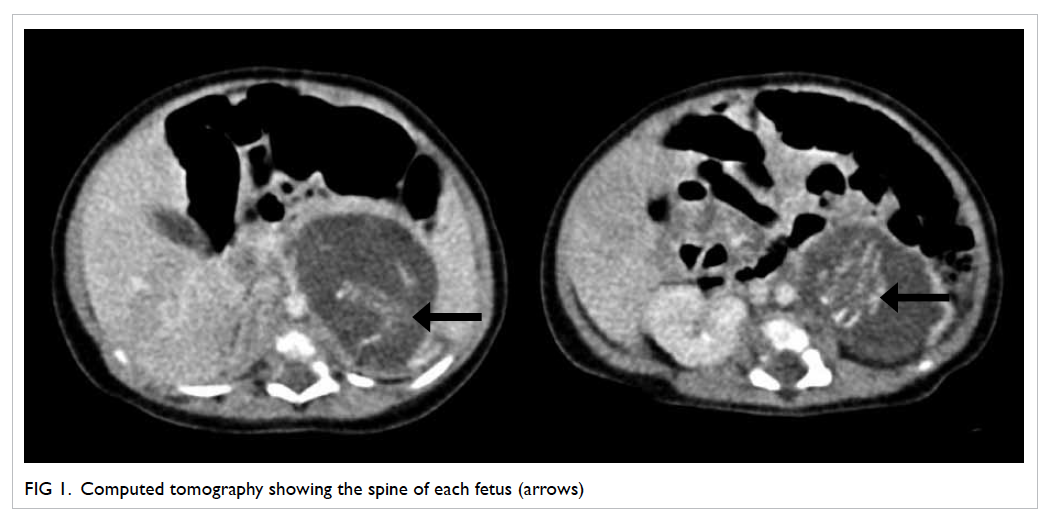

with evidence of bleeding. Another CT scan was

arranged which confirmed that there was a 2.5-cm

intraluminal lesion in the small bowel, suggesting

a probable occurrence of gastro-intestinal stromal

tumour.

Subsequently, single-port laparoscopic

resection of the small bowel tumour under single-balloon

enteroscopic guidance was performed. The

patient was operated on under general anaesthesia

in supine position with prophylactic antibiotics.

The single-balloon enteroscope (Olympus SIF-Q260;

Olympus Medical Systems Corp, Japan) was

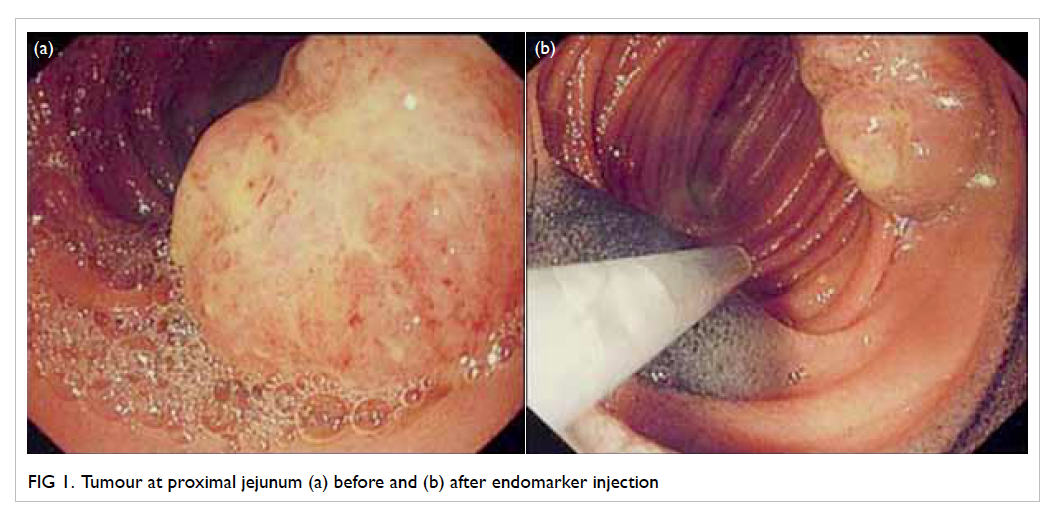

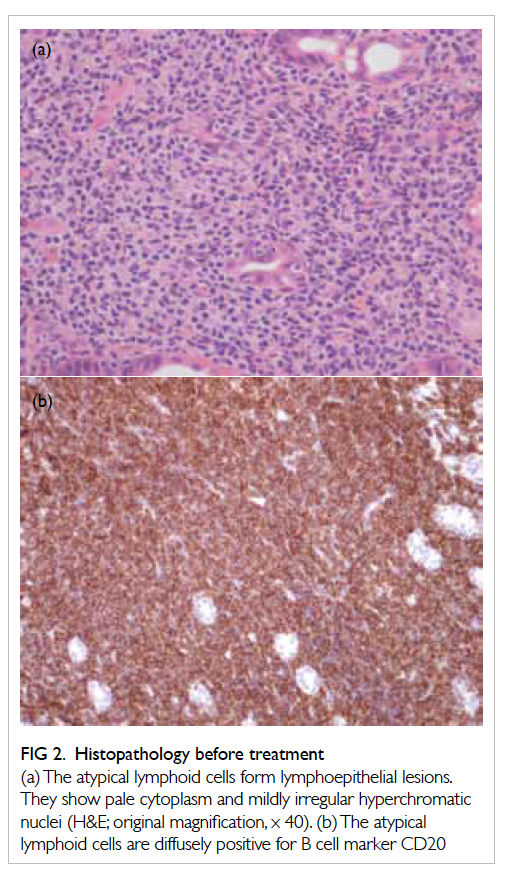

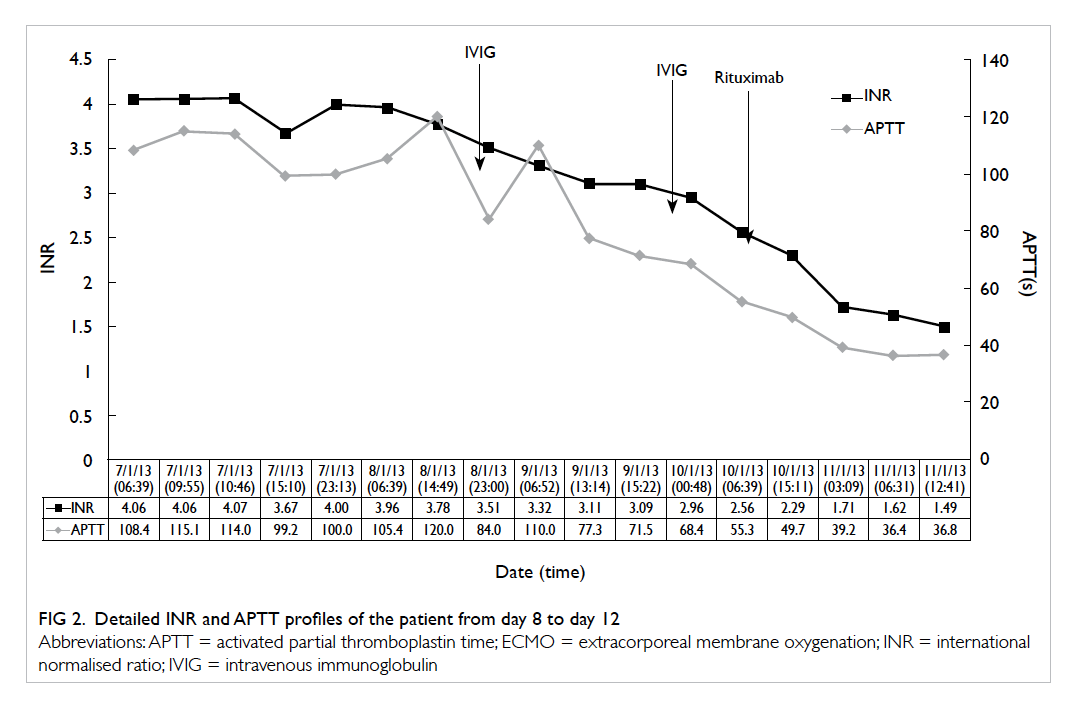

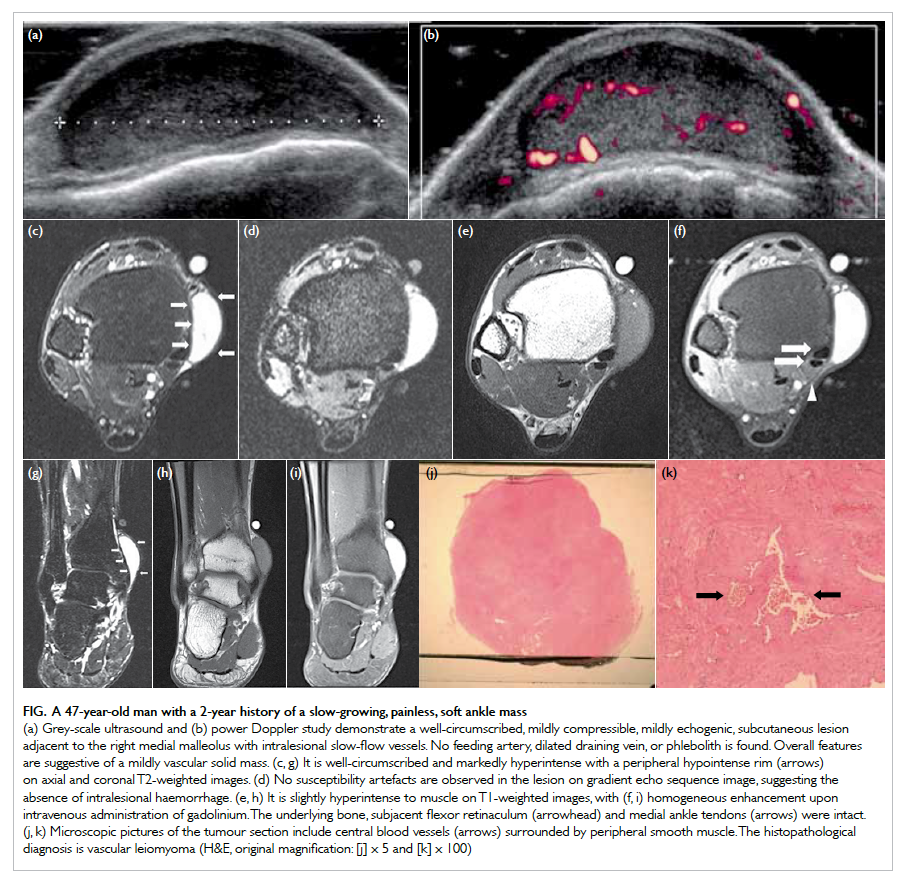

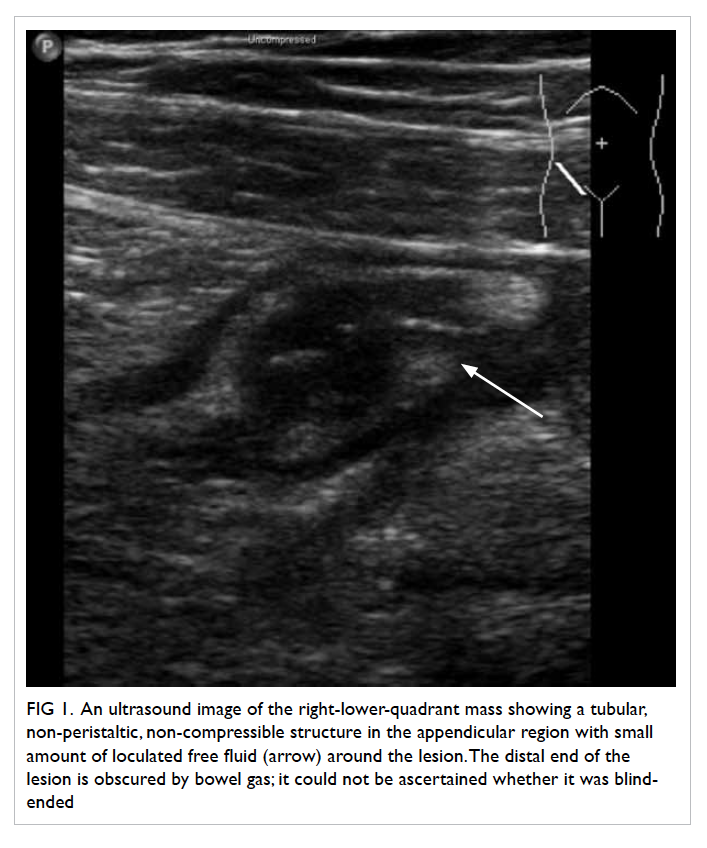

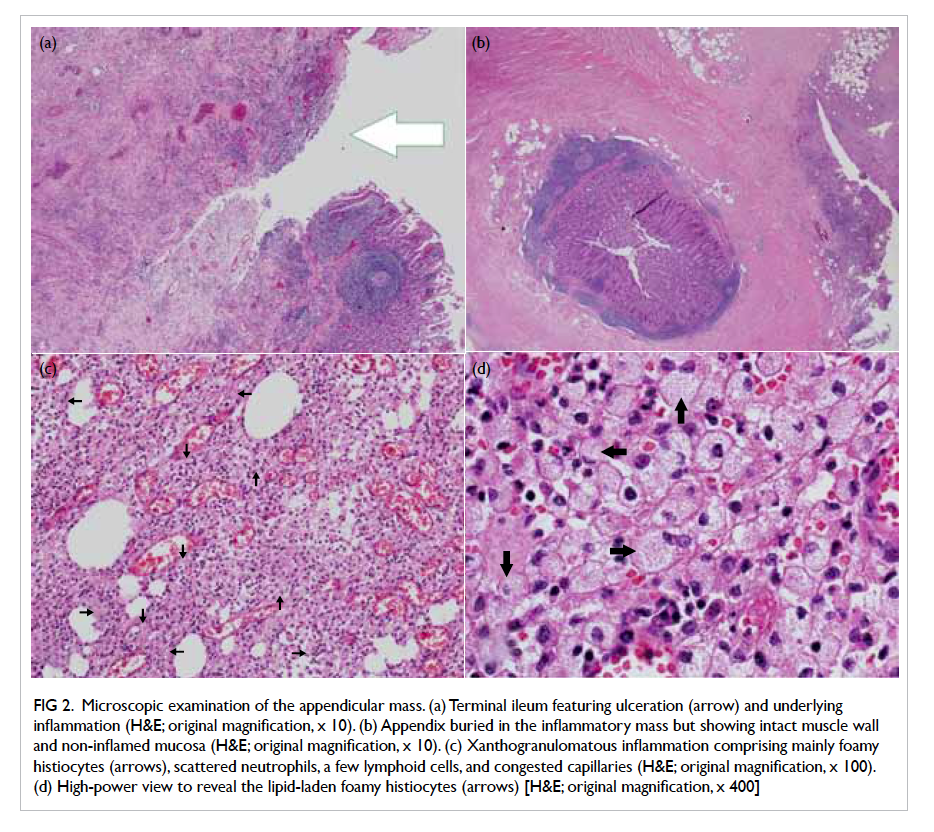

used to locate the site of tumour (Fig 1a). The lesion was marked with endomarker (Fig 1b) and lipiodol

injection, and the enteroscope was left in situ in

order to guide the site of skin incision. Fluoroscopy

and transillumination of the small bowel at the site

of lesion confirmed that the tumour was situated in

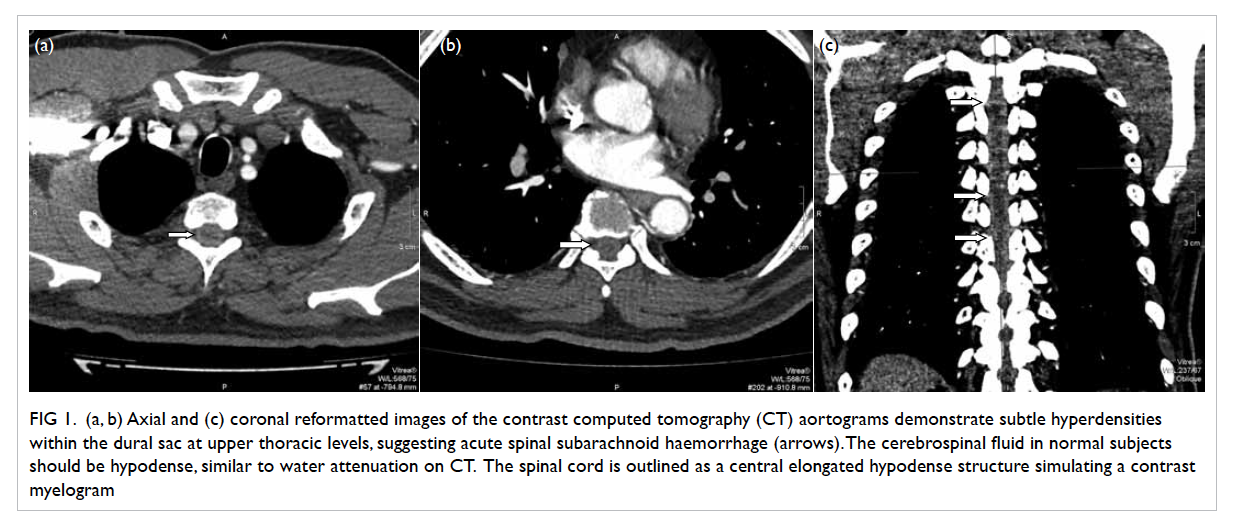

the left upper quadrant of the abdomen (Figs 2a and 2b).

Figure 2. (a) Fluoroscopy scan and (b) transillumination of tumour. (c) Retrieval of small bowel and (d) length of incision

A 2-cm incision was made for laparoscopic

procedure using a Hassan laparoscopic port that was

inserted with an 8-degree laparoscope with working

channel (OLYMPUS A5252A laparoscope; Olympus

Medical Systems Corp, Germany). Laparoscopy

procedure confirmed that there were no suspicious

hepatic and peritoneal nodules. The diseased part

of the small bowel was taken out using a grasper

through the working channel after extension of the

skin wound (Fig 2c). Usual small bowel resection

was done with primary anastomosis using linear

staplers and the entire procedure lasted for about

225 minutes.

The patient tolerated the whole procedure

well and his recovery was satisfactory. He gradually

resumed oral feeding and was fit for discharge on

day 3 after the procedure.

Discussion

Midline laparotomy incision is often a straightforward

procedure for treatment and resection of

small bowel lesions. The long laparotomy wound,

however, may cause a lot of pain, leading to prolonged

hospital stay and more analgesic requirement that

may impair respiratory function especially in patients

with advanced age and multiple co-morbidities.

Although capsule endoscopy for identification

of small bowel pathologies1 2 has become prevalent

in patients with occult gastro-intestinal bleeding,

sometimes it renders the operation difficult to

accurately determine the site of lesion and locate the

tumour.

The recent advances in surgical technology

and development of new techniques have made

minimally invasive procedures possible, like robotic

surgery and endoscopic resection. However, the

installation of these surgical instruments takes up a

lot of space in the operating theatre and increases

the cost of enhancement, not to mention the huge

maintenance cost.3 4 As such, we present a case of

minimally invasive small bowel resection which is

cost-effective to be adopted by most hospitals.

To recap, the aim of minimally invasive surgery

is to reduce surgical morbidity with smaller and less

wound while maintaining pathological clearance

and safety. In our design, the use of enteroscope

provided accurate localisation of the pathology by

direct visualisation.5 After confirming the position

of the pathology, the skin incision could be precisely

made on top of the lesion. Before excising the lesion,

laparoscopy was also performed to make sure that

there was no intra-abdominal metastatic deposit.

The wound was extended to 4.5 cm and this allowed

the diseased small bowel to be retrieved for resection

as in an open procedure (Fig 2d). The instruments

used are readily available in most hospitals and the

procedure can be performed at a relatively lower

cost.

Single-balloon enteroscope, the procedure

used in our case, is a recently developed technology

for diagnosing small bowel pathology. The setup of this safe enteroscope is simple.6 Moreover, some

evidence bore out that the learning curve of single-balloon

enteroscope is insignificant.7 8 Previous

study also showed that single-balloon enteroscope

provided a diagnostic yield similar to double-balloon

enteroscope which requires more technical skills.9

In this operation, three types of localisation

methods were adopted after position of the tumour

was confirmed by enteroscopy. These included

lipiodol injection, transillumination to localise the

incision site, and endomarker injection to find out

precisely where the tumour was located.

Lipiodol injection at the site of tumour allows

localisation of lesion under fluoroscopic guidance,

which is useful to guide the site for skin incision.

It can be done before operation, hence saves time

during intra-operative enteroscopy. The exact

position of the tumour, however, may not be easily

located by laparoscope after identification of the

incision site.

In such situations, injection of endomarker

before operation is recommended during

laparoscopy as this enables better visualisation of

the portion of the diseased bowel to be retrieved

for further resection. However, endomarker cannot

replace lipiodol in localisation of lesion as it is not

radio-opaque and cannot aid localisation of skin

incision site.

Alternatively, transillumination using

enteroscope allows real-time localisation of the

incision site and this is superior to merely injecting

lipiodol. However, the risk of complications arising

from intra-operative enteroscope may be hiked up

and the operating time may be extended.

To facilitate the operation and shorten the

time required, preoperative enteroscopy rather than

intra-operative enteroscopy should be employed.

The injection of lipiodol and endomarker can be

done before operation. As an initial attempt of

our de-novo technique in this case, we decided to use

intra-operative enteroscopy with transillumination

for real-time tumour localisation even though the

operating time was inevitably prolonged.

In addition to the above methods, the use of

endoclip is considered a possible option for accurate

localisation. Since endoclip is radio-opaque, it

can serve both purposes for incision site and

tumour localisation under fluoroscopic guidance.

Nevertheless, the accuracy could be affected due to

the risk of dislodgement of these endoclips.

Conclusion

Enteroscope is a safe option for guiding minimally

invasive small bowel resection with accurate

localisation of pathology. There are different ways

for localisation including the use of endomarker,

lipiodol injection, transillumination as well as

endoclip. Large-scale studies using these techniques

should be considered in order to understand the

efficacy of such newer methods.

References

1. Mavrogenis G, Coumaros D, Bellocq JP, Leroy J. Detection

of a polypoid lesion inside a Meckel’s diverticulum using

wireless capsule endoscopy. Endoscopy 2011;43 Suppl 2

UCTN:E115-6.

2. Mavrogenis G, Coumaros D, Lakhrib N, Renard C, Bellocq JP,

Leroy J. Mixed cavernous hemangioma-lymphangioma

of the jejunum: detection by wireless capsule endoscopy.

Endoscopy 2011;43 Suppl 2 UCTN:E217-8.

3. Amodeo A, Linares Quevedo A, Joseph JV, Belgrano E,

Patel HR. Robotic laparoscopic surgery: cost and training.

Minerva Urol Nefrol 2009;61:121-8.

4. Kim CW, Baik SH. Robotic rectal surgery: what are the

benefits? Minerva Chir 2013;68:457-69.

5. Ress AM, Benacci JC, Sarr MG. Efficacy of intraoperative

enteroscopy in diagnosis and prevention of recurrent

occult gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Surg 1992;163:94-9. Crossref

6. Yoshiya S, Sugimachi K, Nakamura S, et al. Preoperative

diagnostic value of single-balloon enteroscopy for

successful surgical treatment of three independent-origin

gastrointestinal malignant tumors: report of a case. Surg

Today 2011;41:1007-10. Crossref

7. Upchurch BR, Sanaka MR, Lopez AR, Vargo JJ. The

clinical utility of single-balloon enteroscopy: a single-center

experience of 172 procedures. Gastrointest Endosc

2010;71:1218-23. Crossref

8. Tsujikawa T, Saitoh Y, Andoh A, et al. Novel single-balloon

enteroscopy for diagnosis and treatment of the small

intestine: preliminary experiences. Endoscopy 2008;40:11-5. Crossref

9. Domagk D, Mensink P, Aktas H, et al. Single- vs. double-balloon

enteroscopy in small-bowel diagnostics: a randomized multicenter trial. Endoscopy 2011;43:472-6. Crossref