Three different ophthalmic presentations of juvenile xanthogranuloma

Hong Kong Med J 2014;20:261–3 | Number 3, June 2014

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj134059

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Three different ophthalmic presentations of juvenile xanthogranuloma

Henry HW Lau, FRCS, FHKAM (Ophthalmology)1;

Wilson WK Yip, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Ophthalmology)1;

Allie Lee, MB, BS2;

Connie Lai, MB, BS, FHKAM (Ophthalmology)1;

Dorothy SP Fan, FRCS, FHKAM (Ophthalmology)2

1 Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Prince of Wales

Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

2 Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, The Chinese

University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Eye Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Henry HW Lau (henrylau@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Three cases of juvenile xanthogranuloma from

two ophthalmology departments were reviewed.

Clinical histories, ophthalmic examination, physical

examination, investigations, and treatment of these

cases are described. A 4-month-old boy presented

with spontaneous hyphema and secondary

glaucoma. He was treated with intensive topical

steroid and anti-glaucomatous eye drops. The

hyphema gradually resolved and the intra-ocular

pressure reverted to 11 mm Hg without any other

medication. Biopsy of his scalp mass confirmed the

diagnosis of juvenile xanthogranuloma. A 31-month-old

boy presented with a limbal mass. Excisional

biopsy of the mass was performed and confirmed it

was a juvenile xanthogranuloma. A 20-month-old

boy was regularly followed up for epiblepharon and

astigmatism. He presented to a paediatrician with

a skin nodule over his back. Skin biopsy confirmed

juvenile xanthogranuloma. He had no other ocular signs. Presentation of juvenile xanthogranuloma

can be very different, about which ophthalmologists

should be aware of. Biopsy of the suspected lesion is

essential to confirm the diagnosis.

Introduction

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) is a benign

histiocytic skin disorder encountered primarily

in infancy and childhood. Approximately 10%

of these patients exhibit ocular manifestations,

whose presentations vary. Although patients can

be asymptomatic, occasionally they have associated

glaucoma and even blindness.1 2

Case reports

Case notes from 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2009

in two ophthalmology departments were reviewed.

Three cases with a diagnosis of JXG were identified.

The clinical histories, ophthalmic examination

findings, physical examination, investigation results,

and treatment of these patients are described.

Case 1

A 4-month-old boy with glucose-6-phosphate

dehydrogenase deficiency was referred by a

paediatrician because of right eye redness for 2

weeks. His antenatal and birth history was otherwise

unremarkable. He had no recent history of eye injury.

On examination, his right eye was diffusely injected,

with a hazy right cornea and irregular pupil. There was a 1-mm organised blood clot in the anterior

chamber of his right eye. No rubeosis was noted.

Left eye examination was unremarkable, with a clear

cornea and no hyphema. Fundal examination of the

left eye was normal. The intra-ocular pressure (IOP)

of right eye was 48 mm Hg and in the left eye it was

14 mm Hg. In both eyes the corneal diameters (10.5

x 10 mm) were normal for his age.

Blood tests—including complete blood

picture, clotting profile, renal and liver function

tests—were performed to rule out metabolic or

haematological abnormalities, but yielded nil

abnormal. Ultrasonography of his right eye showed

a clear vitreous and the retina was flat without any

intra-ocular mass. Magnetic resonance imaging

of the brain and orbits was also performed, but

revealed no intra-ocular mass. X-rays assessing his

bones showed no features of non-accidental injury.

The patient’s medical and family history was non–contributory.

He was treated intensively with 1% topical

prednisolone acetate (Pred Forte ophthalmic

suspension USP, Allegan) 1 drop every hourly and

anti-glaucomatous eye drops including 2% topical

dorzolamide hydrochloride–timolol maleate

ophthalmic solution (Cosopt; MSD) 1 drop twice daily and topical 0.03% bimatoprost ophthalmic

solution (LUMIGAN; Allergan) 1 drop at night. The

hyphema gradually resolved and IOP normalised

(right eye, 14 mm Hg) without medication. No iris

mass was noted after hyphema subsided. There

was a skin nodule over the scalp but no other skin

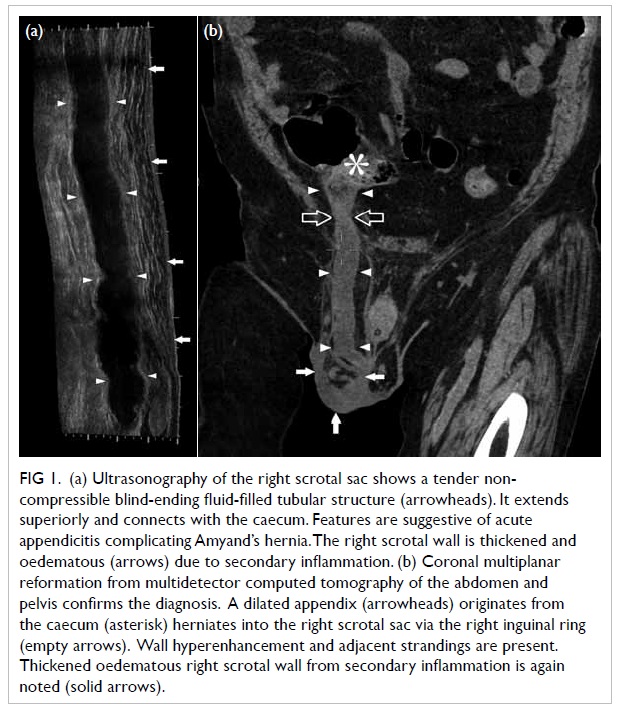

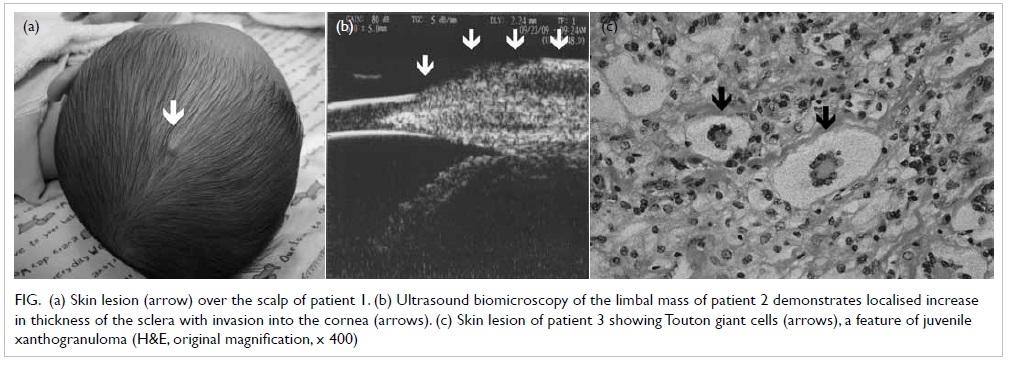

lesion was identified (Fig a). Biopsy of the scalp

lesion yielded skin tissue with cellular intradermal

expansion by histiocytes, which were uniform with

small vesicular nuclei and foamy cytoplasm. The

features were compatible with JXG.

The hyphema did not recur over the 2-year

follow-up. His IOP remained normal (right eye

11 mm Hg and left eye 15 mm Hg) without any

medication. The latest visual acuity of both eyes was

20/30.

Figure. (a) Skin lesion (arrow) over the scalp of patient 1. (b) Ultrasound biomicroscopy of the limbal mass of patient 2 demonstrates localised increase in thickness of the sclera with invasion into the cornea (arrows). (c) Skin lesion of patient 3 showing Touton giant cells (arrows), a feature of juvenile xanthogranuloma (H&E, original magnification, x 400)

Case 2

The second case was a 31-month-old boy who was born full-term with a normal birth weight (2.7 kg)

and had normal development all along. He presented

to us with an enlarging nasal limbal mass over the

right eye. The mass had been noticed by his mother

for 9 months. The patient was treated elsewhere

with topical steroids and antibiotics but the lesion

was unresponsive. Incisional biopsy of the lesion was

performed and histopathology was reported to show

‘inflammation’. Further increase in size of the lesion

was noted after the biopsy. No other skin lesion was

evident elsewhere. Ultrasound biomicroscopy of

the right eye demonstrated a localised increase in

thickness of the sclera at the site of the lesion with

invasion into the cornea and the borders were ill-defined

(Fig b).

Using Kay Single Pictures, the unaided visual

acuity of the right eye was 20/60 and of the left eye

was 20/40. Examination under general anaesthesia

was performed. There was a right-sided 6-mm limbal

yellowish-grey mass over the nasal region with an

adjacent lipid keratopathy of 1 mm. The other eye

anterior segment examination was unremarkable.

The IOP (right eye 15 mm Hg and left eye 14 mm Hg),

corneal diameter (12.5 mm x 12 mm), and fundal

examination of both eyes were all normal.

The lesion was excised and a partial sclerectomy

was performed. Bared sclera was covered by

conjunctiva. Intra-operatively, the mass did not

show any deep scleral involvement. After removal of

the lesion, the bare area of the sclera was covered

with a conjunctival graft. Histopathology sections

showed a JXG comprising aggregates of histiocytes

and Touton giant cells, situated in a fibrous stroma

covered by non-keratinising squamous epithelium.

Postoperatively he was started on topical 1%

prednisolone acetate ophthalmic suspension USP

(PRED FORTE; Allergan) 1 drop 6 times daily and

topical 0.5% levofloxacin (Cravit; Santen) 1 drop

4 times daily. Recovery was uneventful. Upon

last follow-up 14 months after surgery, the best-corrected visual acuity of both eyes was 20/20 with

no evidence of recurrence.

Case 3

The third case was a 20-month-old boy who was

regularly followed up because of epiblepharon. His

unaided visual acuity of both eyes was 20/50. He also

had astigmatism. Refraction of the right eye was -1.00

D/-1.00 D x 39 and for the left eye it was -1.00 D/

-2.00 D x 157. He presented to a paediatrician with

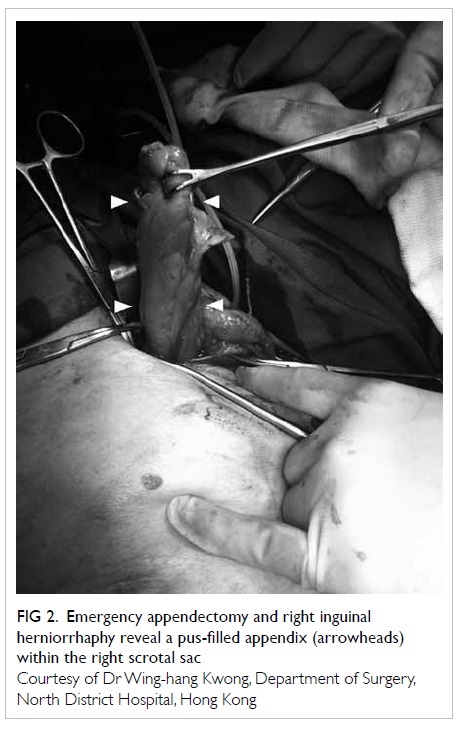

a skin nodule over his back. Biopsy of the skin lesion

yielded sections with bland epidermis. There was

a well-demarcated nodule in the upper and lower

dermis that was composed of histiocytes and foam

cells, and a few Touton giant cells were seen (Fig c).

These features were compatible with the diagnosis

of JXG. He had no other ocular signs and symptoms

including features of a hyphema or an ocular mass.

Upon last follow-up 15 months after surgery,

unaided visual acuity of both eyes was 20/50 with no

evidence of recurrence.

All three cases yielded a good visual prognosis

and there was no recurrence of the disease.

Discussion

Ocular involvement is the most common

extracutaneous manifestation of JXG. Risk factors

for the development of eye diseases include the

number of skin lesions, and being under 2 years old.3

This condition can affect the orbit, iris, ciliary body,

cornea, and episclera, with the iris being the most

commonly affected.4 Patients can present with iris

nodules which can be quite vascular and may bleed

spontaneously causing hyphema and secondary

glaucoma.5

Zimmerman1 first reported JXG. In his series

of 53 infants and young children with JXG, he

identified five presenting clinical features of intra-ocular

involvement.1 This included an asymptomatic

localised or diffuse iris tumour, unilateral glaucoma,

spontaneous hyphema, red eye with signs of uveitis,

and congenital or acquired iris heterochromia.

However, JXG can sometimes be difficult to be

diagnosed and can mimic melanomas in the eye.6

Ocular JXG can be diagnosed by a skin biopsy if

typical skin lesions are present. However, absence of

skin lesion cannot rule out JXG, because skin lesions

often regress spontaneously. Fifty percent of patients never develop skin lesions and may first present to

the ophthalmologist.7 Treatment depends on the

presenting signs and symptoms. Topical steroids can

be used for hyphema, and anti-glaucomatous eye

drops can be used if there is secondary glaucoma. In

the presence of an ocular mass or skin mass, biopsy

of the suspected lesion is essential to confirming

the diagnosis. Sometimes JXG does not warrant

treatment. However, if extracutaneous involvement

exists, surgery, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy may

become necessary.8

In this case series, the presentation of JXG

was very different in the three patients. Treatment

modalities should be individualised and tailored for

different clinical presentations. Ophthalmologists

should be aware of the various ophthalmic

presentations in JXG. For skin lesions and systemic

signs and symptoms, we should collaborate with

paediatricians and dermatologists to provide holistic

patient care.

Declaration

No conflicts of interest were declared by the authors.

References

1. Zimmerman LE. Ocular lesions of juvenile xanthogranuloma. Nevoxanthoedothelioma. Am J Ophthalmol 1965;60:1011-35.

2. Mocan MC, Bozkurt B, Orhan D, Kuzey G, Irkec M. Juvenile xanthogranuloma of the corneal limbus: report of two cases and review of the literature. Cornea 2008;27:739-42.

3. Chang MW, Frieden IJ, Good W. The risk intraocular juvenile xanthogranuloma: survey of current practices and assessment of risk. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996;34:445-9. CrossRef

4. Chu AC. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. In: Champion RH, Burton JL, Burn DA, Breathnach SM, editors. Rook's textbook of dermatology. 6th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2004: 2323-5.

5. Vendal Z, Walton D, Chen T. Glaucoma in juvenile xanthogranuloma. Semin Ophthalmol 2006;21:191-4. CrossRef

6. Fontanilla FA, Edward DP, Wong M, Tessler HH, Eagle RC, Goldstein DA. Juvenile xanthogranuloma masquerading as melanoma. J AAPOS 2009;13:515-8. CrossRef

7. Howard J, Crandall A, Zimmerman P, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma of the iris of an adult presenting with spontaneous hyphema. Ophthalmic Pract 2001;19:124-9.

8. Hernandez-Martin A, Baselga E, Drolet BA, Esterly NB. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. J Am Acad Dermatol 1997;36:355-67. CrossRef