DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144230

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Isolated spinal artery aneurysm: a rare culprit of subarachnoid haemorrhage

Tony HT Sung, MB, ChB, FRCR;

Warren KW Leung, FHKCR, FHKAM (Radiology);

Bill MH Lai, MB, BS, FRCR;

Jennifer LS Khoo, FHKCR, FHKAM (Radiology)

Department of Radiology, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Tony HT Sung (sht557@ha.org.hk), (tttony100@gmail.com)

Abstract

Isolated spinal artery aneurysm is a rare lesion

which could be accountable for spontaneous spinal

subarachnoid haemorrhage. We describe the case

of a 74-year-old man presenting with sudden

onset of chest pain radiating to the neck and

back, with subsequent headache and confusion.

Initial computed tomography aortogram revealed

incidental finding of subtle acute spinal subarachnoid

haemorrhage. A set of computed tomography scans

of the brain showed further acute intracranial

subarachnoid haemorrhage with posterior

predominance, small amount of intraventricular

haemorrhage, and absence of intracranial vascular

lesions. Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging

demonstrated a thrombosed intradural spinal

aneurysm with surrounding sentinel clot, which was

trapped and excised during surgical exploration.

High level of clinical alertness is required in order

not to miss this rare but detrimental entity. Its

relevant aetiopathological features and implications

for clinical management are discussed.

Introduction

Aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) is

an uncommon but fatal clinical event. The reported

incidence in a recent international population-based

epidemiological study ranged between 2 and 16 per

100 000 population,1 and the mortality rate ranged

from 8% to 67%.2 Among all SAH cases, less than

1% are considered to originate from the spine.3 We

present a case of isolated spinal artery aneurysm

as a rare culprit of spinal and intracranial SAH to

illustrate the diagnostic challenge, its relevant

aetiopathological features, and implications for

clinical management.

Case report

A 74-year-old Chinese man with a history of

hypertension and ischaemic heart disease presented

to the Accident and Emergency Department in

February 2013 for sudden onset of chest pain

radiating to the neck and back. Clinical examination

and electrocardiogram on admission showed no

evidence of myocardial infarction. Initial working

diagnosis of acute aortic dissection was also

excluded with urgent computed tomography (CT)

aortogram. On retrospective analysis, subtle but

definite hyperdensities within the thecal sac at upper

thoracic levels were noted, suggestive of acute spinal

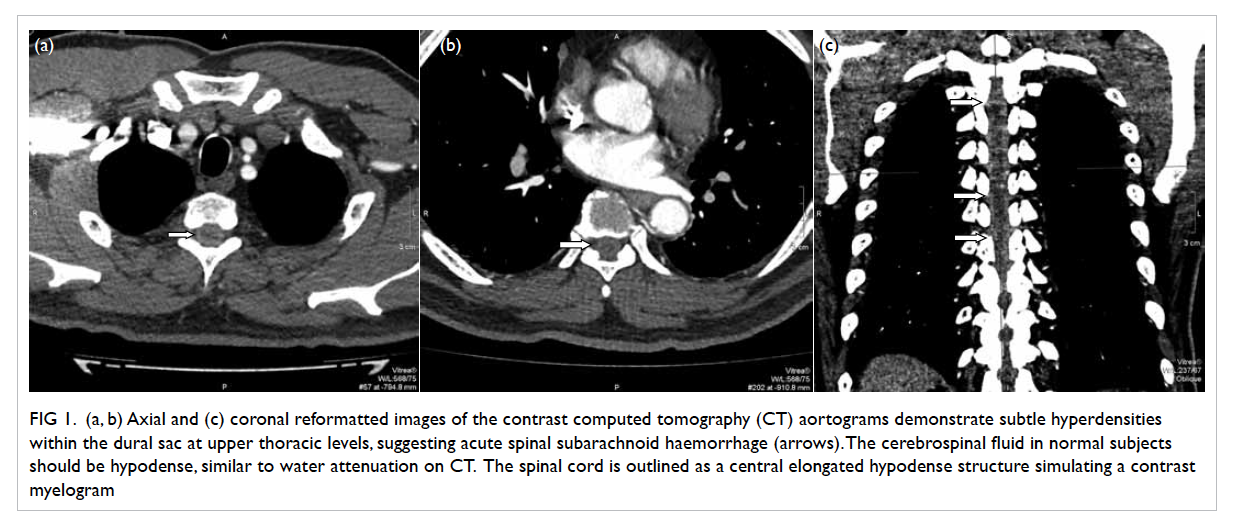

SAH (Fig 1).

Figure 1. (a, b) Axial and (c) coronal reformatted images of the contrast computed tomography (CT) aortograms demonstrate subtle hyperdensities within the dural sac at upper thoracic levels, suggesting acute spinal subarachnoid haemorrhage (arrows). The cerebrospinal fluid in normal subjects should be hypodense, similar to water attenuation on CT. The spinal cord is outlined as a central elongated hypodense structure simulating a contrast myelogram

The patient developed gradual progressive

headache and confusion requiring intubation on

the fourth day of admission. Plain CT of the brain

at that time revealed further diffuse acute SAH

with predominance over the posterior aspect, as

well as a small amount of acute intraventricular

haemorrhage. No skull vault fracture was observed.

Concurrent CT cerebral arteriogram and venogram

did not demonstrate any aneurysms or venous

sinus thrombosis. Subsequent digital subtraction

angiogram (DSA) of cerebral arteries performed on

the next day was unremarkable.

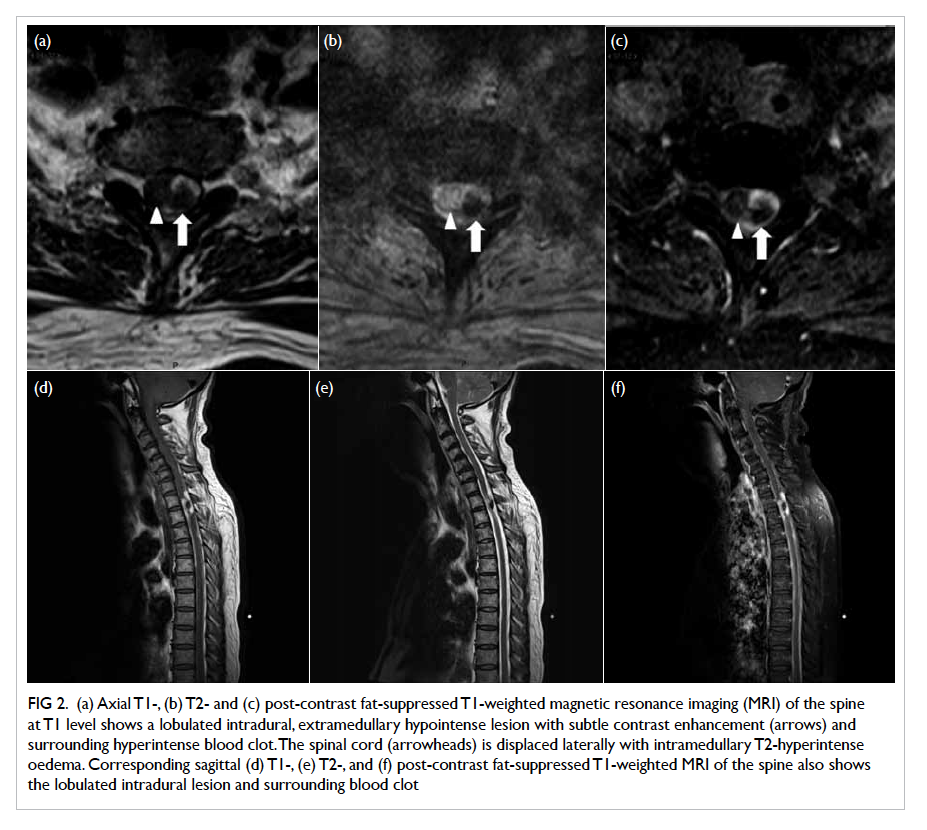

In view of posterior predominance of the

intracranial SAH with negative cerebral angiograms,

an urgent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the

brain and cervical spine (Fig 2) was performed for

suspected subtle intracranial pathology and a spinal

origin of SAH (observed rarely). A lobulated 8-mm

intradural, extramedullary lesion with internal

hypointense signal was seen at the T1/2 level abutting

the lateral surface of the spinal cord. Trace contrast

enhancement was noted within the lesion. Adjacent

hyperintense signal and susceptibility artefacts

within the dural sac were also observed, suggestive of

sentinel clot formation. The spinal cord was displaced

slightly by the lesion with associated mild cord

oedema. Radiological differential diagnosis at this

juncture included cavernoma, largely thrombosed

spinal aneurysm, other exophytic haemorrhagic

intramedullary tumour or slow-flow arteriovenous

malformation (AVM).

Figure 2. (a) Axial T1-, (b) T2- and (c) post-contrast fat-suppressed T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine at T1 level shows a lobulated intradural, extramedullary hypointense lesion with subtle contrast enhancement (arrows) and surrounding hyperintense blood clot. The spinal cord (arrowheads) is displaced laterally with intramedullary T2-hyperintense oedema. Corresponding sagittal (d) T1-, (e) T2-, and (f) post-contrast fat-suppressed T1-weighted MRI of the spine also shows the lobulated intradural lesion and surrounding blood clot

Subsequent laminectomy and surgical

exploration were performed for definitive diagnosis,

which revealed a 7-mm saccular aneurysm

surrounded by fibrin and an old haematoma from

C7 to T2 level. The aneurysm arose from and

was incorporated with the radicular artery at T1

level, showing internal partial thrombosis. The

aneurysmal sac was trapped and carefully excised

without jeopardising the rest of the arterial supply

to the cord. The patient had good clinical recovery

in postoperative rehabilitation with no further

neurological complaints.

Discussion

Compared with more common causes of spinal SAH

like AVM, dural arteriovenous fistula (dAVF) and

haemorrhagic spinal cord tumours, spinal artery

aneurysm remains a rare entity with a reported

incidence of less than 1 in 3000 spinal angiograms,

according to a large-scale review by Pia and

Djindjian.4 Ever since the first case report on spinal

aneurysm back in 1930,5 experience from various

studies remains limited mainly to isolated case

reports and case series with small sample sizes.

Spinal aneurysms are distinct from intracranial

counterparts in several ways. First, they occur

mostly along the course of their parent arteries

which have a small calibre and are less affected

by atherosclerosis.6 On the contrary, intracranial

aneurysms are well known for their predilection

for branching points of large-sized arteries which

are more haemodynamically challenged. Second,

spinal aneurysms tend to be small in size, whereas

giant aneurysms are exclusively found intracranially,

especially in patients with connective tissue disease.

Third, many spinal aneurysms are found to be

dissecting aneurysms in histology, which explains

their fusiform shape and lack of a surgical neck.5 This

hinders direct surgical clipping during treatment

planning.

For aetiology, isolated spinal aneurysms, as

in our case, are rare lesions. More commonly, they

are associated with concomitant vascular lesions

or occlusions which recruit the spinal artery as a

collateral route for supplying and increasing local

blood flow. This, in turn, imposes haemodynamic

stress and induces aneurysm formation along the

parent arteries. Reported associations include spinal

cord AVM,7 dAVF,8 aortic coarctation,5 Moyamoya

disease,9 and bilateral vertebral artery occlusion.10

Another group of spinal aneurysms is related to

underlying vasculopathies. Common examples

include collagen vascular disease such as rheumatoid

arthritis,11 mycosis,12 and syphilis.5

The diagnosis of spinal artery aneurysm

could be challenging and delayed due to its rarity.

Most patients present with headache and backache

related to aneurysmal rupture and SAH. Neurological deficits including

paraparesis, quadriplegia, and cord compression

have also been reported.13 As for investigations,

MRI and DSA of the spine are sufficient to

demonstrate the location and vascular anatomy of

a spinal artery aneurysm on most occasions which,

in turn, are valuable for treatment planning by

neurosurgeons. The position of the aneurysm with

respect to the spinal cord determines whether the

anterior approach for transthoracic vertebrectomy

or posterior laminectomy is most appropriate. In a

large-scale literature review by Geibprasert et al,14

32 spinal artery aneurysms were studied, in which

the majority (62.5%) arose from the anterior spinal

artery. Origin from the radicular artery, as in our

case, was scarcely seen (n=2). The authors also

observed that posterior spinal artery aneurysms

were predominantly isolated dissecting aneurysms.

On the contrary, those from the anterior spinal

artery are more diverse in aetiology, eg, related to

candidiasis and connective tissue disease, which

implies a non-surgical management approach with

medical treatment for the underlying disorder. Even

for isolated dissecting aneurysms from the anterior

axis, surgical ligation or endovascular embolisation

is still limited by increased risk of postoperative

complications including spinal cord infarction due to

possible compromise of the dominant arterial supply

to the cord. Options of surgical approach include

resection and wrapping of the aneurysmal sac, with

possible microvascular reconstruction in individual

cases. Rare cases of spontaneous complete healing

of the dissecting aneurysm have been reported,12 but

prompt treatment should not be delayed due to the

associated severe complications.

Conclusion

Spinal artery aneurysms are rare culprits of SAH, with different

morphological features of their intracranial

counterparts. Associations with concurrent

vascular lesions and vasculopathy are frequent,

with a minority of cases being isolated in aetiology.

Magnetic resonance imaging and DSA of the spine

show their merit in delineating the location and

vascular anatomy of a spinal artery aneurysm,

which are key determinants in management

planning. Surgical treatment should be prompt and

performed cautiously in view of possible substantial

neurological deficit when the arterial supply of the

cord is jeopardised.

References

1. Feigin VL, Lawes CM, Bennett DA, Barker-Collo SL, Parag

V. Worldwide stroke incidence and early case fatality

reported in 56 population-based studies: a systematic

review. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:355-69. Crossref

2. Nieuwkamp DJ, Setz LE, Algra A, Linn FH, de Rooij

NK, Rinkel GJ. Changes in case fatality of aneurysmal

subarachnoid haemorrhage over time, according to age,

sex, and region: a meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:635-42. Crossref

3. van Gijn J, Kerr RS, Rinkel GJ. Subarachnoid haemorrhage.

Lancet 2007;369:306-18. Crossref

4. Pia HW, Djindjian R. Spinal angiomas: advances in

diagnosis and therapy. Berlin: Springer Verlag; 1987.

5. Rengachary SS, Duke DA, Tsai FY, Kragel PJ. Spinal arterial

aneurysm: case report. Neurosurgery 1993;33:125-9;

discussion 129-30. Crossref

6. Leech PJ, Stokes BA, ApSimon T, Harper C. Unruptured

aneurysm of the anterior spinal artery presenting as

paraparesis. Case report. J Neurosurg 1976;45:331-3. Crossref

7. Konan AV, Raymond J, Roy D. Transarterial embolization

of aneurysms associated with spinal cord arteriovenous

malformations. Report of four cases. J Neurosurg 1999;90(1 Suppl):148-54.

8. Malek AM, Halbach VV, Phatouros CC, et al. Spinal dural

arteriovenous fistula with an associated feeding artery

aneurysm: case report. Neurosurgery 1999;44:877-80. Crossref

9. Walz DM, Woldenberg RF, Setton A. Pseudoaneurysm of

the anterior spinal artery in a patient with Moyamoya: an

unusual cause of subarachnoid hemorrhage. AJNR Am J

Neuroradiol 2006;27:1576-8.

10. Kawamura S, Yoshida T, Nonoyama Y, Yamada M, Suzuki

A, Yasui N. Ruptured anterior spinal artery aneurysm: a

case report. Surg Neurol 1999;51:608-12. Crossref

11. Toyota S, Wakayama A, Fujimoto Y, Sugiura S, Yoshimine

T. Dissecting aneurysm of the radiculomedullary artery

originating from extracranial vertebral artery dissection

in a patient with rheumatoid cervical spine disease: an

unusual cause of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Case report.

J Neurosurg Spine 2007;7:660-3. Crossref

12. Berlis A, Scheufler KM, Schmahl C, Rauer S, Götz F,

Schumacher M. Solitary spinal artery aneurysms as a

rare source of spinal subarachnoid hemorrhage: potential

etiology and treatment strategy. ANJR Am J Neuroradiol

2005;26:405-10.

13. Yahiro T, Hirakawa K, Iwaasa M, Tsugu H, Fukushima

T, Utsunomiya H. Pseudoaneurysm of the thoracic

radiculomedullary artery with subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Case report. J Neurosurg 2004;100(3 Suppl Spine):312-5.

14. Geibprasert S, Krings T, Apitzsch J, Reinges MH, Nolte

KW, Hans FJ. Subarachnoid hemorrhage following

posterior spinal artery aneurysm. A case report and review

of the literature. Interv Neuroradiol 2010;16:183-90.