Hong

Kong Med J 2019 Aug;25(4):305–11 | Epub 5 Aug 2019

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REVIEW ARTICLE CME

Common urological problems in children: primary

nocturnal enuresis

Ivy HY Chan, MB, BS, FHKAM (Surgery); Kenneth KY

Wong, PhD, FHKAM (Surgery)

Department of Surgery, The University of Hong Kong,

Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Kenneth KY Wong (kkywong@hku.hk)

Abstract

Enuresis is a common complaint in children, with

a prevalence of around 15% at age 6 years. Evidence suggests that

enuresis could affect neuropsychiatric development. The condition may

represent an entire spectrum of underlying urological conditions. It is

important to understand the difference between monosymptomatic and

non-monosymptomatic enuresis. Primary monosymptomatic enuresis can be

managed efficaciously with care in different settings, like primary

care, specialist nursing, or paediatric specialists, while

non-monosymptomatic enuresis requires more complex evaluation and

treatment. The diagnosis, investigation, and management of

the two types of enuresis are discussed in this review.

Introduction

Enuresis is a common problem in children worldwide.

Despite this, many parents underestimate its impact. The reactions from

parents of children with enuresis are diverse, with various misconceptions

among patients and parents.1 Some

parents delay seeking medical assessment to avoid stigmatisation. Many

parents believe that enuresis will be cured with age and does not need any

treatment. Yet, left untreated, this problem may persist into adulthood.2

The most common enuresis condition is primary

monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis (PMNE). It can also be a symptom of

other urological conditions like detrusor overactivity, neurogenic

bladder, or posterior urethral valve.

The underlying causes of PMNE and

non-monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis are different. Their treatment and

prognosis thus differ. Both conditions nonetheless can affect patients’

psychological development, self-confidence, and participation in social

events.

What is enuresis?

The term ‘enuresis’ refers to nocturnal urinary

incontinence, while urinary incontinence is involuntary leakage of urine.

This differentiation is very important in establishing diagnosis and hence

formulating treatment plans. The American Psychiatric Association defines

enuresis as recurrent urine leakage in bed >2 nights per week for >3

weeks in patients aged ≥5 years.

In contrast, PMNE refers to those patients who have

never been dry for >6 months and have urinary leakage during sleep time

only. They do not have any other urinary symptoms like daytime urinary

leakage, urinary frequency, or urgency. Hence, patients with symptoms in

addition to isolated bedwetting warrant different evaluation and should be

regarded as having non-monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis. The

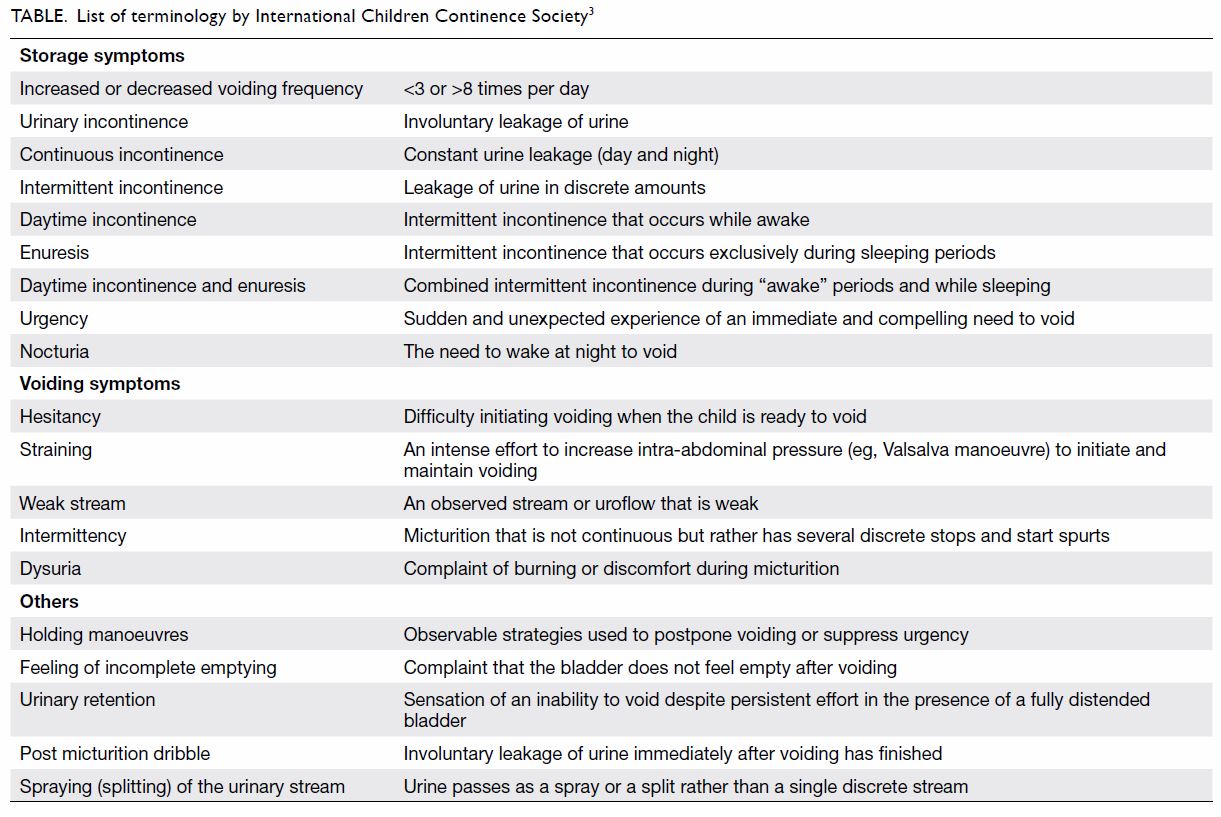

International Children Continence Society (ICCS) has listed the

definitions of different terminology for all related symptoms and signs (Table 3).

Prevalence

The prevalence of enuresis in children is usually

quoted as 10% to 15% at age 6 years, 5% at age 10 years, and 0.5% to 1%

among teenagers/young adults.4 A

large-scale epidemiological study in Hong Kong carried out in 2006 showed

the prevalence of nocturnal enuresis as 16.1% at age 5 years, 3.14% at age

9 years, and 2.2% at age 19 years.5

It is more common in boys in all age-groups. The prevalence of nocturnal

enuresis decreases as age increases. However, patients who have daytime

urinary incontinence and those with enuresis >3 nights per week seem to

have symptoms that persist to adulthood, according to a 2004 study that

showed the static prevalence of enuresis over different age-groups from

age 16 to 40 years.6 Thus, the

phenomenon of ‘growing out of enuresis’ may not apply in all patients.

Aetiology and risk factors

Enuresis is a complex condition to which genetic,

physiological, and psychological factors contribute. Some patients have a

definite cause of enuresis or urinary incontinence, like neurogenic

bladder, detrusor overactivity, vaginal reflux, or stress incontinence.

Presence of daytime symptoms definitely warrants a detailed investigation.

it has been hypothesised that small bladder volume in children plays a

role in PMNE. Nonetheless, further studies showed that there was a genetic

component to this condition. Indeed, a Finnish twin study showed a higher

concordance rate of enuresis for monozygotic than dizygotic twins.7 Furthermore, there is a strong association with

parental history of childhood enuresis.8

In this study, the overall odds ratio of having nocturnal enuresis and

urinary incontinence was 10.1 times higher if the father or mother also

had a history of nocturnal enuresis or urinary incontinence.

It is also known that antidiuretic hormone, or

vasopressin, is very important in controlling and concentrating the urine

volume. The normal physiological increase in night-time vasopressin

level/diurnal level has been shown to be absent in some enuretic children.9 10

There is a phenomenon of ‘nocturnal polyuria’, characterised by increased

nocturnal urine output due to a dysregulated diurnal rhythm of

antidiuretic hormone, with a larger volume of urine production at night

time.11 Adults with nocturnal

polyuria syndrome will need to get up to urinate a few times every night.

This group of children will benefit from desmopressin treatment.

Enuresis is classified as a sleep disorder by the

American Psychiatric Association in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic

and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Enuresis is correlated with

the quality of sleep and the arousability of the child. Poor sleep

quality, periodic movement during sleep, and inadequate sleep are factors

associated with enuresis and night-time diuresis.12

13 The awareness of the

relationship between enuresis and obstructive sleep apnoea is also

increasing.13 In 2014, Kovacevic

et al14 showed resolution of

nocturnal enuresis after adenotonsillectomy. Indeed, a systematic review

on this topic also showed that after adenotonsillectomy, an improvement of

nocturnal enuresis was seen in >60% of patients, with a complete

resolution rate in excess of 50%.15

There is also strong association between attention

deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and enuresis. Children with enuresis

had 2.88 times increased odds of having ADHD compared with those without

enuresis in a population study in the United States.16 Conversely, children with ADHD have also been shown

to have a 2.1 times higher risk of enuresis.17

In addition, treating ADHD with medications like atomoxetine can decrease

the number of wet nights in children with co-morbid enuresis.18

Until now, no conclusions about the causal

relationship between enuresis and childhood behavioural problems could be

drawn. Yet, patients with refractory enuresis may warrant neuropsychiatric

evaluation.19

Why do we need to treat enuresis?

The prevalence of enuresis decreases with age.

Parents may therefore ask whether enuresis really needs to be treated. The

answer is yes because, first, enuresis is a symptom but not a diagnosis.

After specialist medical assessment, other underlying urological problems

may be suspected and further investigations instigated. Second, enuresis

is often associated with poor school performance and decreased quality of

life, self-esteem, and psychosocial development.19

20 A study showed significant

improvement in self-esteem with higher self-concept scores after 6 months

of treatment with desmopressin or alarm therapy.21

Finally, enuresis can persist to adulthood if not treated properly.

About one third of the patients with childhood

enuresis reported symptoms of nocturia despite resolution of enuresis.

About one quarter of them still reported some kind of urinary

incontinence.

Initial assessment and evaluation

Detailed history taking is the key to success in

treating enuresis or urinary incontinence. Bladder function and cognitive

control of voiding take time to develop. By definition, we define enuresis

as persistent urinary incontinence in children aged >5 years. Before

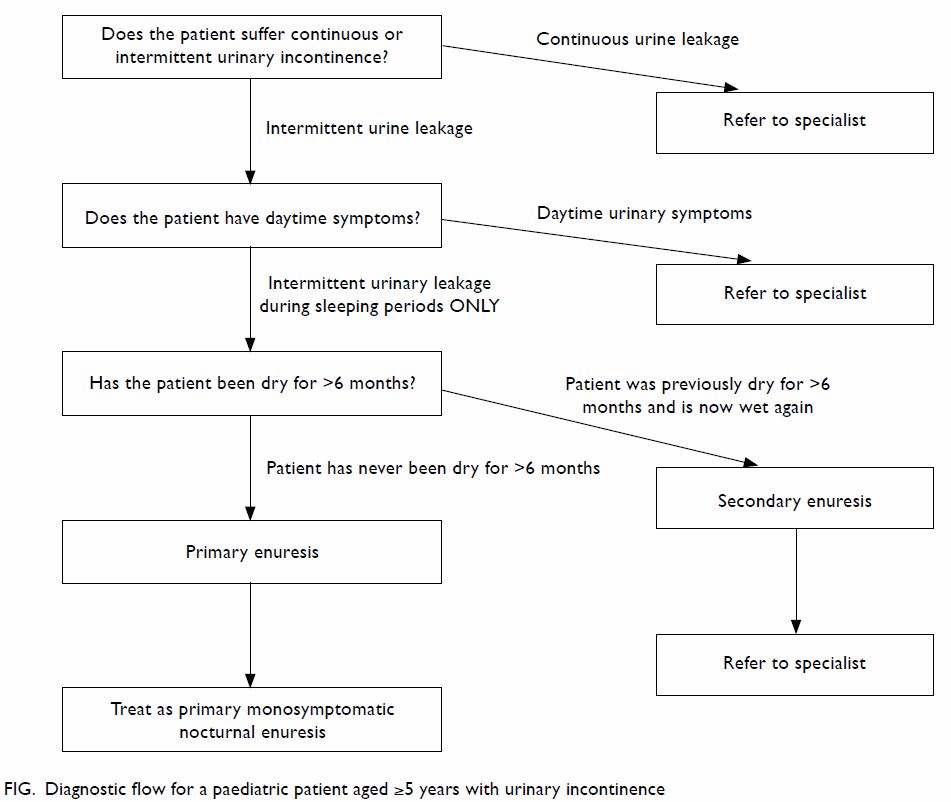

the detailed history, there are three important questions that one should

ask (Fig).

Does the patient suffer continuous or intermittent

urinary incontinence?

‘Intermittent incontinence’ is discrete leakage of

urine, whereas ‘continuous incontinence’ is constant urine leakage (both

day and night time). Patients with continuous urinary incontinence usually

have congenital anatomical anomalies, eg, ectopic ureter, exstrophy

variant, etc. These patients will need to be referred to a specialist for

further assessment.

Does the patient have daytime symptoms?

Enuresis per se is simply involuntary leakage of

urine at night time. If patients have symptoms like excessive daytime

urinary frequency (urination >8 times/day), urinary urgency (sudden and

unexpected experience of an immediate and compelling need to void),

daytime urinary incontinence (urine leakage during the awake period),

interrupted urine stream, hesitancy, weak urine stream, or other lower

urinary tract symptoms, they should be referred to a specialist for

further assessment. The list of symptoms, terminology, and definitions is

described in the Table.3

Is this ‘primary enuresis’?

Primary enuresis is defined by the ICCS as a

patient not having been dry for >6 months. If the patient has been dry

for >6 months and then has enuresis again, it is termed secondary, and

the patient should be referred to a specialist for further assessment.

History taking

The aim of history taking is to formulate a correct

diagnosis. As mentioned above, it is important to see whether the patient

has PMNE. If not, the patient may have other conditions like detrusor

overactivity or neurogenic bladder, which may need referral for further

investigation and management. The management of this group of patients is

out of the scope of this review. Questions asked during history taking

should also help to exclude underlying neurological or anatomical

anomalies. Information about bowel function and constipation should be

obtained, as should a brief assessment of psychological history. The

following aspects should be asked.

Urinary symptoms

The following symptoms of urinary storage and

emptying are important.

1. Night-time symptoms: Frequency of bedwetting (times/week), precipitating factors for wetting (eg, long holiday/sleep hours, drinking before bed). This is used to identify the severity of bedwetting.

2. Daytime symptoms: Voiding frequency in daytime (times/day), sudden urgent need to void, habit of voiding postponement, holding manoeuvres (tips of heel pressing on perineum, leg crossing), abdominal straining to void, and interrupted urine stream.

3. Urinary frequency of 3 to 8 times per day is defined as normal by the ICCS. If it is out of this range, the patient may have other problems. The presence of other daytime symptoms may signify that the patient is having non-monosymptomatic enuresis.

1. Night-time symptoms: Frequency of bedwetting (times/week), precipitating factors for wetting (eg, long holiday/sleep hours, drinking before bed). This is used to identify the severity of bedwetting.

2. Daytime symptoms: Voiding frequency in daytime (times/day), sudden urgent need to void, habit of voiding postponement, holding manoeuvres (tips of heel pressing on perineum, leg crossing), abdominal straining to void, and interrupted urine stream.

3. Urinary frequency of 3 to 8 times per day is defined as normal by the ICCS. If it is out of this range, the patient may have other problems. The presence of other daytime symptoms may signify that the patient is having non-monosymptomatic enuresis.

History taking of urinary or voiding symptoms is

often difficult in a child. Adequate time and patience in out-patient

clinics are therefore absolutely necessary. The use of a bladder diary and

enuresis chart is helpful in providing vital information, such as bladder

capacity and the presence of urinary leakage, and helps to identify

underlying bladder dysfunction.

Bowel symptoms

The frequency of bowel movements and the presence

of faecal incontinence should be asked. Bladder and bowel movements are

closely related. Constipation affects the treatment of enuresis: it is

often difficult to completely stop enuresis in a patient with chronic

constipation. Faecal incontinence can also be a symptom of constipation or

underlying spinal cord anomalies.22

Drinking habits

The quantity and quality of drinking during the day

and fluid intake in the evening are important. Evidence of diabetes

insipidus may be obtained from this element of history. With heavy

workloads and tight school schedules in Hong Kong, many patients do not

have adequate fluid intake during daytime. They prefer to drink in the

evening. It is logical to deduce that a large volume of fluid intake in

the evening increases the risk of enuresis. Patients should also be

advised to void before bed. A bladder diary is a vital instrument for the

patient and parents to monitor fluid intake and observe voiding habits.

This diary is shown to the clinician during clinic visits for progress

monitoring.

Possible underlying problems and general medical health

These symptoms include: (a) history of urinary

tract infections, (b) known urological or spinal cord problems, (c)

evidence of ADHD, autism, or other psychological problems, (d) history of

motor development or learning disability, (e) sleep habits, sleep quality

and presence of heavy snoring, and (f) family history, living environment,

or evidence of sexual abuse.

Physical examination

A general physical examination including body

weight and height can help to identify patients with growth retardation or

failure to thrive, which may be suggestive of an underlying disorder. An

abdominal examination can reveal faecal impaction. Examination of the

genitalia and inspection of underwear can identify signs of sexual abuse,

stress incontinence, or faecal incontinence. Dimples or hair tufts in the

lumbosacral area may be caused by occult spinal dysraphism.

A simple urine dipstick test may be helpful when

diabetes mellitus or urinary tract infection is suspected.

Management of primary monosymptomatic nocturnal

enuresis

Once the diagnosis of PMNE is made, advice and

treatment should be given accordingly. The patient and parents should be

educated about the prevalence of enuresis in children and the importance

of treatment. They should know that enuresis is common and that the child

should not be blamed or labelled as lazy. Yet, they should understand that

indolent psychological stress may result if the problem is not dealt with

seriously.

Discussion and general advice

The child should be advised to avoid large amounts

of fluid intake at least 1 to 2 hours before bed, avoid heavy loads of

salt and protein during dinner time, void before bed, and drink adequately

during daytime. Understanding of the patient’s drinking, voiding, and

eating habits is important to treatment adherence and hence success. It is

ideal to keep records on an enuresis chart to illustrate the frequency of

the enuresis and a bladder diary for possible daytime symptoms. Sometimes

it is difficult or unreliable for the patient or caretaker to recall the

pattern of enuresis; keeping a calendar of bed wetting nights should help

to monitor treatment progress. Rewards can also be given for dry nights.

Constipation

Urinary and bowel functions are closely related.

Children with functional constipation are 6.8 times more likely to have

lower urinary tract symptoms, and these patients have higher Voiding

Dysfunction Symptom Scores.23 The

rate of constipation is also much higher in children with urinary

incontinence. After treating the constipation, urinary incontinence

improves, especially in adolescents.24

Bowel habits should be asked, and daily passage of soft stool without

discomfort should be the aim. Principles of treatment should include a

four-step approach: Education, dis-impaction of faeces, prevention of

re-accumulation, and follow-up.25

Advice on fluid intake, fibre intake, and use of laxatives are the common

first-line treatment options. A meta-analysis from the Cochrane library

showed good results of using polyethylene glycol on paediatric patients

with functional constipation.26

Alarm therapy

Enuresis alarms are an effective measure to improve

or cure bedwetting. This is a behavioural therapy that works by

conditioning on arousal. The rationale is to wake up the child with the

alarm once the sensor attached to the child’s pants is wet. The child will

thus gradually learn to wake up before wetting the bed. This requires the

patient to wake up, cease voiding in bed, go to void in the toilet, and

reattach the alarm when they return. In a 2005 meta-analysis, about two

thirds of the children became dry during the treatment period, and nearly

half who persisted with alarm use remained dry after treatment finished.27 Its effect is similar to the use

of desmopressin.28 29 However, its long-term success rate is significantly

higher than that of desmopressin, with 68.8% of one study’s patients who

used enuresis alarms continuing to have dry nights, whereas only 46% of

the desmopressin group did.29

The ICCS recommends that the parent or caregiver

attend the child each time the alarm rings to make sure the child does not

just turn the alarm off to maximise the effect.30

As with other behavioural therapies, this is not an immediate cure. It

requires a trial of a minimum of 2 to 3 months and requires compliance

from the child and family. Despite the promising long-term success rate of

enuresis alarms, the initial dropout rate can be up to 30%.29 This is probably caused by the awkwardness of using

the alarm and the sleep disruption to the whole family. The ICCS also

recommends that the patient be reviewed on the first day of using the

alarm and 2 to 3 weeks after starting use of the alarm to improve

compliance.

Desmopressin

Desmopressin is a synthetic analogue of arginine

vasopressin antidiuretic hormone. It acts on the renal tubules to

concentrate urine. It has been hypothesised that loss of diurnal rhythm of

vasopressin is associated with enuresis in children. In the clinical

setting, desmopressin can rapidly decrease the number of wet nights.31 It has been reported that up to 70% of patients have

dry nights after treatment; yet, 50% of the “successful” patients reported

relapse after stopping the medication.32

Gradual withdrawal of desmopressin is thus advocated to help reduce the

relapse rate.33 Functional bladder

capacity has also been shown to predict the response to desmopressin.

Patients with functional bladder capacity >70% of predicted bladder

capacity were 2 times more likely to respond to desmopressin.34

Desmopressin can be prescribed as tablet or melt

(oral lyophilisate) formulation. It should be taken around 1 hour before

sleep. The melt preparation can help to further decrease fluid intake

before bed35: the patient should

be instructed not to drink any fluid after the medication until the next

morning.

According to ICCS recommendations, the effects of

desmopressin can be evaluated after 2 to 6 weeks with an enuresis diary.36 If there is significant

improvement, treatment can be continued to a maximum of 3 months. If the

patient does not respond well, re-evaluation of symptoms and diagnosis and

referral to a specialist may be needed.

Treatment resistance and other treatment options

Apart from enuresis alarms and desmopressin, there

are other second-line treatment options, but these should ideally be

initiated at the specialist level. It is important to ensure that the

patient is using the enuresis alarm correctly or taking desmopressin daily

before proceeding to second-line treatments. Inability to adhere to the

advice of limiting evening fluid or voiding before bed can also decrease

the overall treatment success rate.

For those patients who respond poorly to the

treatment, re-evaluation should be considered. Questions about bowel

habits and psychiatric conditions should be asked, and a full urine

frequency/volume chart should be recorded. Referral to specialists should

also be considered.

Second-line treatment options include combination

therapy using both enuresis alarm and desmopressin, use of tricyclic

antidepressants, indomethacin, and even daytime diuretics.

Conclusion

Primary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis is a

common condition that can impair a child’s psychosocial development.

Affected children and caretakers should be educated about its prevalence,

potential associated problems, associated co-morbidities, and the

necessity of treatment. It should be distinguished from

non-monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis. Advice about drinking and voiding

habits, use of enuresis alarms, and desmopressin are common treatment

options. Patients with poor response to treatment should be referred to

specialists for re-evaluation.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: IHY Chan.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the article: IHY Chan.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: KKY Wong.

Acquisition of data: IHY Chan.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the article: IHY Chan.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: KKY Wong.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, KKY Wong was not

involved in the peer review process. The other author has no conflicts of

interest to disclose.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Cederblad M, Nevéus T, Åhman A,

Österlund Efraimsson E, Sarkadi A. “Nobody asked us if we needed help”:

Swedish parents experiences of enuresis. J Pediatr Urol 2014;10:74-9. Crossref

2. Goessaert AS, Schoenaers B, Opdenakker

O, Hoebeke P, Everaert K, Vande Walle J. Long-term followup of children

with nocturnal enuresis: increased frequency of nocturia in adulthood. J

Urol 2014;191:1866-70. Crossref

3. Austin PF, Bauer SB, Bower W, et al. The

standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function in children

and adolescents: update report from the standardization committee of the

International Children’s Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn

2016;35:471-81. Crossref

4. Franco I, von Gontard A, De Gennaro M;

International Children’s Continence Society. Evaluation and treatment of

nonmonosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis: a standardization document from the

International Children’s Continence Society. J Pediatr Urol 2013;9:234-43.

Crossref

5. Yeung CK, Sreedhar B, Sihoe JD, Sit FK,

Lau J. Differences in characteristics of nocturnal enuresis between

children and adolescents: a critical appraisal from a large

epidemiological study. BJU Int 2006;97:1069-73. Crossref

6. Yeung CK, Sihoe JD, Sit FK, Bower W,

Sreedhar B, Lau J. Characteristics of primary nocturnal enuresis in

adults: an epidemiological study. BJU Int 2004;93:341-5. Crossref

7. Hublin C, Kaprio J, Partinen M,

Koskenvuo M. Nocturnal enuresis in a nationwide twin cohort. Sleep

1998;21:579-85. Crossref

8. von Gontard A, Heron J, Joinson C.

Family history of nocturnal enuresis and urinary incontinence: results

from a large epidemiological study. J Urol 2011;185:2303-6. Crossref

9. Nørgaard JP, Pedersen EB, Djurhuus JC.

Diurnal anti-diuretic-hormone levels in enuretics. J Urol

1985;134:1029-31. Crossref

10. Rittig S, Knudsen UB, Nørgaard JP,

Pedersen EB, Djurhuus JC. Abnormal diurnal rhythm of plasma vasopressin

and urinary output in patients with enuresis. Am J Physiol 1989;256(4 Pt

2):F664-71. Crossref

11. Rittig S, Schaumburg HL, Siggaard C,

Schmidt F, Djurhuus JC. The circadian defect in plasma vasopressin and

urine output is related to desmopressin response and enuresis status in

children with nocturnal enuresis. J Urol 2008;179:2389-95. Crossref

12. Dhondt K, Raes A, Hoebeke P, Van

Laecke E, Van Herzeele C, Vande Walle J. Abnormal sleep architecture and

refractory nocturnal enuresis. J Urol 2009;182(4 Suppl):1961-5. Crossref

13. Alexopoulos EI, Malakasioti G, Varlami

V, Miligkos M, Gourgoulianis K, Kaditis AG. Nocturnal enuresis is

associated with moderate-to-severe obstructive sleep apnea in children

with snoring. Pediatr Res 2014;76:555-9. Crossref

14. Kovacevic L, Wolfe-Christensen C, Lu

H, et al. Why does adenotonsillectomy not correct enuresis in all children

with sleep disordered breathing? J Urol 2014;191(5 Suppl):1592-6. Crossref

15. Lehmann KJ, Nelson R, MacLellan D,

Anderson P, Romao RL. The role of adenotonsillectomy in the treatment of

primary nocturnal enuresis in children: a systematic review. J Pediatr

Urol 2018;14:53.e1-8. Crossref

16. Shreeram S, He JP, Kalaydjian A,

Brothers S, Merikangas KR. Prevalence of enuresis and its association with

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among U.S. children: results from

a nationally representative study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry

2009;48:35-41. Crossref

17. Mellon MW, Natchev BE, Katusic SK, et

al. Incidence of enuresis and encopresis among children with

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a population-based birth

cohort. Acad Pediatr 2013;13:322-7. Crossref

18. Ohtomo Y. Atomoxetine ameliorates

nocturnal enuresis with subclinical attention-deficit/hyperactivity

disorder. Pediatr Int 2017;59:181-4. Crossref

19. Gulisano M, Domini C, Capelli M,

Pellico A, Rizzo R. Importance of neuropsychiatric evaluation in children

with primary monosymptomatic enuresis. J Pediatr Urol 2017;13:36.e1-6. Crossref

20. Theunis M, Van Hoecke E, Paesbrugge S,

Hoebeke P, Vande Walle J. Self-image and performance in children with

nocturnal enuresis. Eur Urol 2002;41:660-7. Crossref

21. Longstaffe S, Moffatt ME, Whalen JC.

Behavioral and self-concept changes after six months of enuresis

treatment: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics 2000;105(4 Pt

2):935-40.

22. Rasquin A, Di Lorenzo C, Forbes D, et

al. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: child/adolescent.

Gastroenterology 2006;130:1527-37. Crossref

23. Sampaio C, Sousa AS, Fraga LG, Veiga

ML, Bastos Netto JM, Barroso U Jr. Constipation and lower urinary tract

dysfunction in children and adolescents: a population-based study. Front

Pediatr 2016;4:101. Crossref

24. Hodges SJ, Anthony EY. Occult

megarectum—a commonly unrecognized cause of enuresis. Urology

2012;79:421-4. Crossref

25. Burgers RE, Mugie SM, Chase J, et al.

Management of functional constipation in children with lower urinary tract

symptoms: report from the Standardization Committee of the International

Children’s Continence Society. J Urol 2013;190:29-36. Crossref

26. Gordon M, MacDonald JK, Parker CE,

Akobeng AK, Thomas AG. Osmotic and stimulant laxatives for the management

of childhood constipation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;(8):CD009118. Crossref

27. Glazener CM, Evans JH, Peto RE. Alarm

interventions for nocturnal enuresis in children. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev 2005;(2):CD002911. Crossref

28. Perrin N, Sayer L, While A. The

efficacy of alarm therapy versus desmopressin therapy in the treatment of

primary mono-symptomatic nocturnal enuresis: a systematic review. Prim

Health Care Res Dev 2015;16:21-31. Crossref

29. Önol FF, Guzel R, Tahra A, Kaya C,

Boylu U. Comparison of long-term efficacy of desmopressin lyophilisate and

enuretic alarm for monosymptomatic enuresis and assessment of predictive

factors for success: a randomized prospective trial. J Urol

2015;193:655-61. Crossref

30. Neveus T, Eggert P, Evans J, et al.

Evaluation of and treatment for monosymptomatic enuresis: a

standardization document from the International Children’s Continence

Society. J Urol 2010;183:441-7. Crossref

31. Glazener CM, Evans JH. Desmopressin

for nocturnal enuresis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2002;(3):CD002112. Crossref

32. Kwak KW, Lee YS, Park KH, Baek M.

Efficacy of desmopressin and enuresis alarm as first and second line

treatment for primary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis: prospective

randomized crossover study. J Urol 2010;184:2521-6. Crossref

33. Dalrymple RA, Wacogne ID. Gradual

withdrawal of desmopressin in patients with enuresis leads to fewer

relapses than an abrupt withdrawal. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed

2017;102:335. Crossref

34. Rushton HG, Belman AB, Zaontz MR,

Skoog SJ, Sihelnik S. The influence of small functional bladder capacity

and other predictors on the response to desmopressin in the management of

monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis. J Urol 1996;156(2 Pt 2):651-5. Crossref

35. De Bruyne P, De Guchtenaere A, Van

Herzeele C, et al. Pharmacokinetics of desmopressin administered as tablet

and oral lyophilisate formulation in children with monosymptomatic

nocturnal enuresis. Eur J Pediatr 2014;173:223-8. Crossref

36. Vande Walle J, Rittig S, Bauer S, et

al. Practical consensus guidelines for the management of enuresis. Eur J

Pediatr 2012;171:971-83. Crossref